Abstract

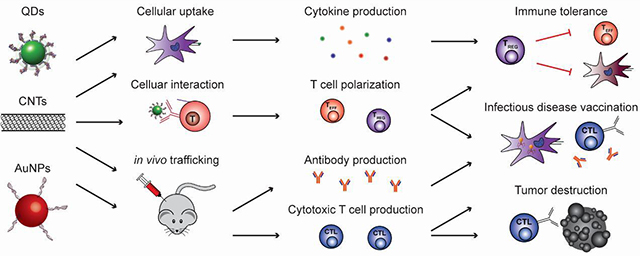

Vaccines and immunotherapies have changed the face of health care. Biomaterials offer the ability to improve upon these medical technologies through increased control of the types and concentrations of immune signals delivered. Further, these carriers enable targeting, stability, and delivery of poorly soluble cargos. Inorganic nanomaterials possess unique optical, electric, and magnetic properties, as well as defined chemistry, high surface-to-volume- ratio, and high avidity display that make this class of materials particularly advantageous for vaccine design, cancer immunotherapy, and autoimmune treatments. In this review we focus on this understudied area by highlighting recent work with inorganic materials – including gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and quantum dots. We discuss the intrinsic features of these materials that impact the interactions with immune cells and tissue, as well as recent reports using inorganic materials across a range of emerging immunological applications.

Keywords: nanomaterial, gold nanoparticle, carbon nanotube, quantum dot, immunology, vaccine and immunotherapy

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The immune system relies on complex interactions of cells and tissues to mount responses to infection, vaccination, or disease. In recent years there is also increasing interest in exploiting the body’s natural immune pathways to combat conditions such as cancer and autoimmunity [1,2]. Materials-based approaches to tune immunity are of particular interest due to advantages such as co-delivery of immune signals, cargo protection, and specific targeting capabilities [3–5]. Notably, many materials themselves exhibit immunomodulatory properties, leading to direct stimulation or regulation of immune pathways [6–11]. One realization from this discovery is that material properties are critically important in determining the effectiveness of candidate vaccines or immunotherapies because these carriers directly impact the response to the other active immune components. From another perspective, these same studies highlight the potential impact of gaining greater control over the interactions of vaccines and immunotherapies with target immune cells and tissues. Inorganic nanomaterials (NMs) differ from other biomaterials (e.g., polymers, lipids) that have been widely reviewed in the immune engineering field [12–16] because they are derived almost entirely from non-natural materials. This characteristic creates unique size-dependent structural, optical, electric, and magnetic properties that can be exploited for immunological applications through targeting of multiple immune signals, enhanced stability, and delivery of otherwise insoluble cargo. Here we discuss this topic across four areas, including i) the inherent immunomodulatory properties of inorganic NMs, and the application of this class of materials to ii) infectious disease, iii) cancer immunotherapy, and iv) autoimmune disease. While a library of inorganic NMs is quickly expanding, we illustrate important themes using key categories such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), quantum dots (QDs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and silicon or iron oxide nanoparticles. Before moving into these areas, we first provide some immunological background and material considerations.

The immune cascade is triggered by antigen recognition

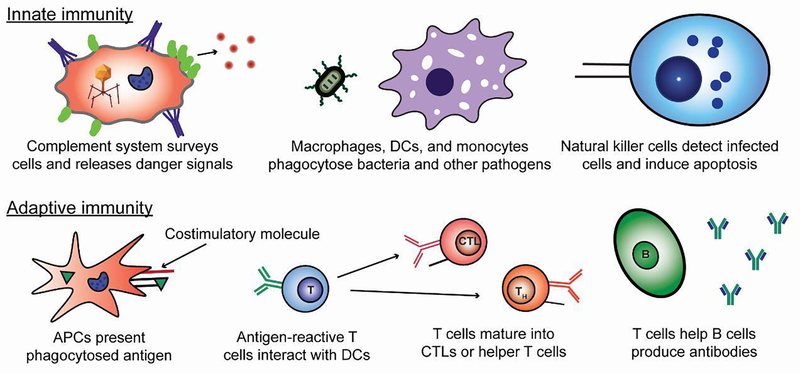

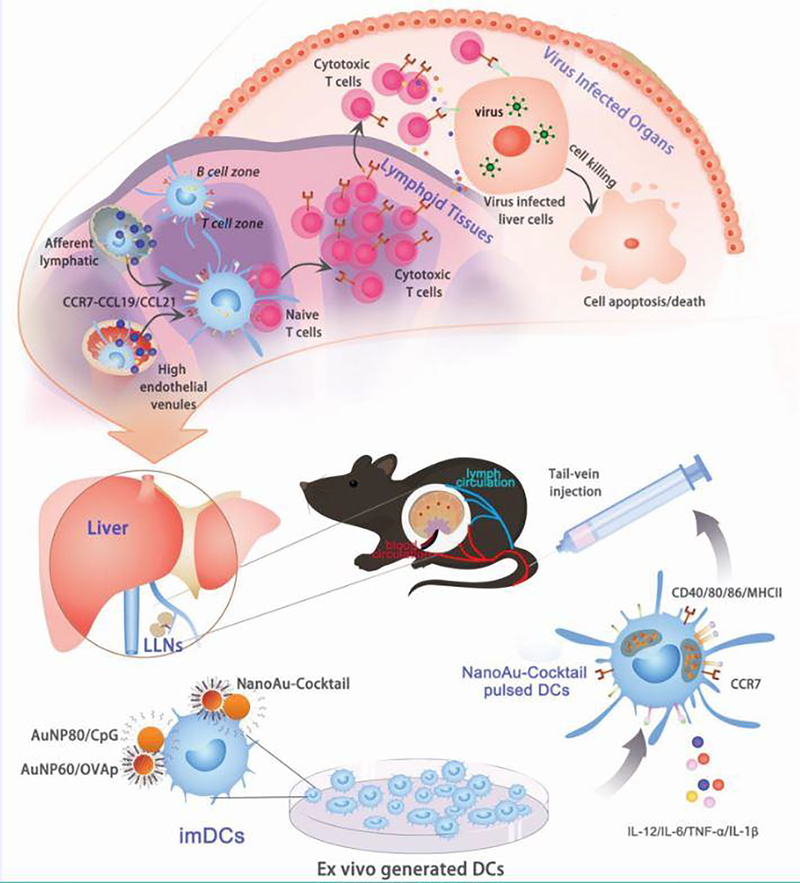

The immune system functions across two key interconnected arms: innate and adaptive (Figure 1). The innate immune system is the body’s first line of defense and includes cells such as macrophages that engulf pathogens, and natural killer (NK) cells that induce cell death (“apoptosis”) in infected host cells [17]. This arm of the immune system relies on the ability of pattern recognition receptors to respond to molecular patterns associated with viruses and bacteria, or other types of danger (e.g., heat, toxins).

Figure 1.

Innate immunity refers to the arm that of the immune system that involves the phagocytosis of pathogens and direct killing of infected cells. Adaptive immunity requires the presentation of antigen along with costimulatory signals to produce mature T cells and antibodies targeted at pathogens and infected cells.

In the adaptive immune system, pathogens – or fragments of pathogens termed “antigens” – travel to immune tissues, including lymph nodes (LNs) and spleen. This process can occur by passive drainage through lymphatic vessels, or through antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that have phagocytosed pathogens and antigens prior to actively migrating to LNs or other sites of antigen presentation [18]. In LNs, APCs such as dendritic cells (DCs) process and present the antigen on their surface by display in specialized proteins called major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs). This presentation is accompanied by costimulatory molecules and leads to the activation of T cells and B cells specific for a given antigen. T cells can differentiate into cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) with antigen-specific direct killing capabilities specialized to combat intracellular pathogens, such as viruses [19]. Other types of T cells – helper T cells (TH), for example – adopt a supportive role and are characterized by the types of signaling molecules (e.g. cytokines) they produce. Lastly, B cells that become activated secrete antibodies that can immobilize extracellular pathogens and toxins or tag a specific target for engulfment or destruction.

The processes just outlined are not carried out unchecked, but instead, are part of a constant balance between immune activation (e.g., against a pathogen) and immune regulation that conserves resources and protects self-tissue from mistaken attack by the immune system. These latter processes – termed immune tolerance – are particularly important, as some T and B cells naturally develop receptors with reactivity for host molecules found in the body [20]. Inflammation and other attacks against self-molecules are prevented through functional tolerance, which relies on mechanisms including deletion of these self-reactive cells, suppression of inflammatory cells by regulatory T cells (TREGS), and receptor editing. During autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and type 1 diabetes (T1D), aspects of these tolerance mechanisms fail, leading to inflammation and attack of host tissue [21].

Vaccination and immunotherapy have revolutionized disease treatment and prevention

Over the past century, prophylactic vaccination has become a standard practice, resulting in the eradication of diseases such as polio and small pox. This strategy relies on the host immune system’s ability to respond to antigen exposure and create “memory.” Most existing vaccines drive B cells to produce antibodies that can, even years later, protect against subsequent antigen exposure. A typical vaccine consists of an antigen and an immunostimulatory molecule, termed an adjuvant. The mechanism of the most commonly used adjuvants, aluminum salts, is still not fully understood. For this reason, an area being heavily investigated for vaccination is development of agonists that stimulate specific immune warning pathways, promoting a more predictable and molecularly-defined response. One such pathway involves toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize mainly bacterial and viral products, allowing these cues to trigger high levels of inflammation in response. Agonists of these receptors have been investigated in many clinical trials for conditions ranging from cancer to allergies [22].

The immune engineering field has rapidly developed in the past decade, with exciting ideas emerging to improve both preventative vaccines against infectious agents, as well as new therapeutic vaccines or immunotherapies targeting cancer and autoimmunity. For example, the tumor microenvironment fosters growth and metastasis in part due to the immunosuppressive characteristics of these tissues, which deactivates immune cells seeking to destroy the tumor. These and other challenges have driven interest in strategies to generate potent, tumor-specific T cells that can overcome this immunosuppressive environment [23]. Another important area is that of immune tolerance during autoimmunity, inflammatory disease, and transplantation. This trend is emerging because immunotherapy has the potential to turn off or regulate the immune responses that underpin these conditions. In autoimmune disease, for example, the immune system recognizes and attacks healthy cells and tissue; approaches to correct these defects without inhibiting other healthy immune responses would be beneficial. Both cancer and autoimmunity are examples of therapeutic vaccines, technologies to harness the immune system to treat patients that are already sick, as opposed to the traditional preventative context vaccines are applied in [14]. Materials, including both natural and inorganic, are increasingly investigated in the field of immunotherapy as delivery vehicles for immune signals, to exploit intrinsic immunogenic properties of materials, and even as imaging agents. Inorganic NMs offer some unique aspects for these applications. Before delving into the immunological applications, we first provide some key inorganic NM concepts and properties, including preparation methods and unique characteristics.

Material Considerations

Given the developing role that inorganic NMs could play in immunological applications, we begin by initially defining what a NM is for the purposes of this review. There is no universally accepted definition, but one definition with broad support is a material derived by an engineered process that has at least one dimension at a scale of <100 nm [24, 25]. This engineered derivation is meant to define the material as man-made and not naturally occurring, while use of the word “material” distinguishes NM from synthetic chemicals. NMs come in two generalized categories that are colloquially classified as “soft” and “hard” NMs. Soft NMs include classical polymers, dendrimers, liposomes, and has been recently extended to include biological derivatives such as DNA origami and recombinantly-modified viral protein scaffolds. Many soft NMs such as polymers, for example, have already seen extensive use in immunological applications as drug delivery agents, display scaffolds, excipients, and even adjuvants. In contrast, hard NMs are typically synthesized from metals or semiconductors. The number of available “hard” NMs continues to grow with each passing year and now include subclasses such as nanoparticles (NPs), nanorods (NRs), nanotubes, nanocapsules, nanosheets, and others. It is the growing use of these latter inorganic NMs within immunological applications that we focus upon here.

There are many considerations to account for in designing NMs for a given biological application – with more yet to be discovered. These considerations are of particular relevance to immunology since essentially every material property has been shown to have some direct impact on interactions with the immune system. Some of these properties include the physicochemical properties of a NM – which determine interactions with other molecules such as cells or proteins, how the NMs are modified for a given purpose – since this impacts the ability to display antigens and other biomolecules, and, equally importantly, the available characterization tools. The latter is important since knowing the composition and properties of the materials are a prerequisite for any application. Some key considerations across these areas are described below.

Physicochemical Properties

Inorganic NMs are considered “value-added” materials in that they often display unique size-dependent or quantum-confined properties that, in many cases, are a major contributor as to why the NM is of interest for exploitation in immune-applications. A prime example is the photoluminescence and extraordinary large multiphoton action cross-sections of semiconductor QDs, which can allow for deep-tissue imaging [26]. As will be shown repeatedly below, this feature is particularly advantageous in applications such as tracking lymphatic drainage. More generally, inorganic NMs – and especially NPs, provide a host of inherent properties that cumulatively can be of benefit for immune targeting applications. These include a size range (<15 nm) that allows for extended long-term circulation in the blood system and extremely high surface-to-volume ratios that allow for high avidity display of molecules such as antigens (critical for vaccines). This feature can also support delivery of multiple, mixed cargo molecules (e.g. antigens and immunomodulatory drugs), and resistance to chemical degradation, which has direct relevance to the material’s viable lifetime in vivo.

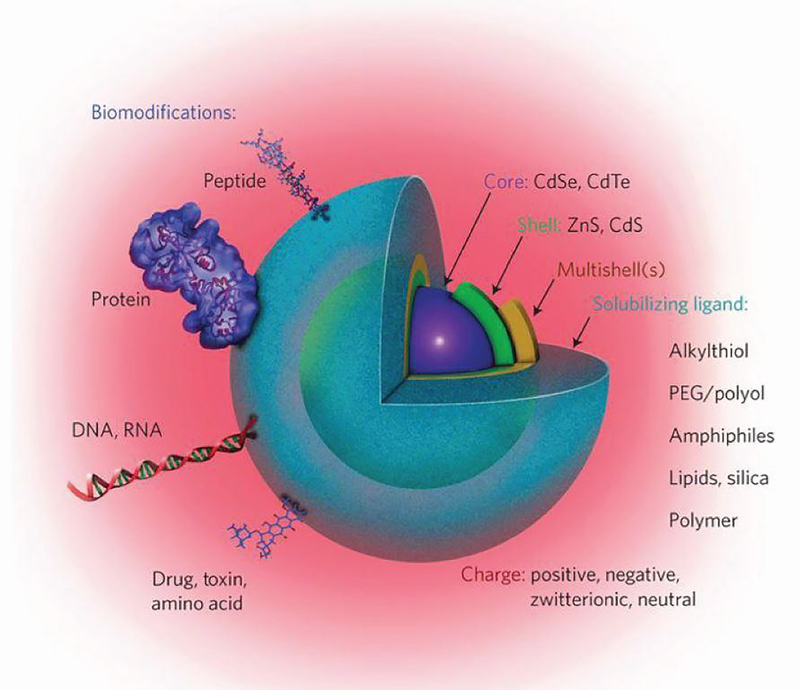

Inorganic NMs differ from molecules like drugs or proteins in significant ways, even though they may be in the same size range. The molecules that make up a drug or a monoclonal antibody formulation are often all considered identical, particularly for approved therapeutics. This is not true for a NM formulation, which is an ensemble containing many distinct, but closely related, species. Using AuNPs as an example, a given sample is typically polydisperse with a distribution of sizes exhibiting a Gaussian profile centered on the average diameter. This means the number of atoms constituting such NPs are also variable. NM surfaces are not uniform at the molecular level, and may display vertices, defects, lattices, and edges, amongst other facets. Many NPs, such as semiconductor QDs, have multilayer structures with a core and shell, or multiple layers of shells [24, 27]. The coatings used to make NMs biocompatible and any biological moiety attached at the surface can be considered further layers in the NM structure (Figure 2). The net charge of a NM is dictated by the groups present and displayed around its surface at the bulk solution interface. Moreover, in solution, NPs commonly exhibit a Debye-Hückel charge counter layer surrounding the particle, making prediction of the charge character complicated [27]. The net charge of NP-biomolecular hybrid can be a major determinant of its ability to be taken up by cells or interact with other ubiquitous biomolecules, especially in a non-specific manner. Lastly, NMs can diffuse in solution, albeit at a slower rate than a similarly-sized biomolecule, and display complex hydrodynamic diameters that are hard to predict given they consist of hard, insoluble materials surrounded by dissolved components. Each of these properties clearly influences how NMs are taken up in cells, how the NMs may drain through the lymphatic system, as well as the interactions with other molecules in vivo. Further, it remains unclear how small differences in a given NM property, such as a slight difference in diameter, impact the interactions with the immune system, and ultimately, the type or effectiveness of response.

Figure 2.

Schematic of a semiconductor QD bioconjugate highlighting the multilayer structure, colloidal solubilizing ligand, and biomodifications that can be present in such structures. Adapted with permission from Springer Nature: Nature Nanotechnology Meta-analysis of cellular toxicity for cadmium-containing quantum dots, E. Oh, et al., Copyright 2016 [39].

Colloidal Stabilization

Aside from certain small metallic oxides, most hard NP materials have no intrinsic solubility of their own, thus requiring surface modification with what are termed “surface ligands” to enable dissolution or stabilization in aqueous environments. This aspect becomes critical in immune application as the NP surface character is largely determined by the ligand and its properties (e.g. charge or hydrophobicity). Thus, these modifications directly dictate the chemical characteristics the body sees and how it interacts with a NM.

Several representative examples surrounding NP colloidal stabilization chemistry for biological application can be used to illustrate some of the problems commonly encountered. Some NPs such as AuNPs are synthesized directly in buffer using nucleating/stabilizing surface ligands that provide colloidal stability through either intrinsic charge (e.g., cetyltrimethylammonium bromide - CTAB) or the presence of appended poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) groups [28, 29]. Molecules such as CTAB are known to be cytotoxic, while PEG can make a NP more chemically inert [30]. Other NPs, such as QDs, are frequently synthesized at high temperature in organic phase and require either encapsulation or a complete surface “cap” exchange for aqueous phase transfer [31]. Large molecular weight amphiphilic polymers provide a set of hydrophobic groups that interdigitate with the organic molecules already present on the NP’s surface, while their hydrophilic surfaces mediate colloidal stability. This approach tends to add significantly to the NP’s hydrodynamic diameter but helps maintain good quantum yield by protecting the core/shell structure from water and charge interactions. This would yield a hydrophilic QD that is quite bright, but rather large for efficient drainage in the host. This last point also highlights that an approach to preparing a NP for biological – and especially immunological – application has to balance solubility, size, and bioaccessibility. Smaller ligands can also be used for cap-exchange of QDs and AuNPs. In these cases, a terminal thiol, for example, provides direct surface coordination, while charged, zwitterionic, or PEG groups mediate colloidal stability. If the charged groups are exclusively amines or carboxyls, this composition will limit stability to a pH regime dictated by that group’s pKa, yet the same groups are also often used as sites for further bioconjugation reactions. Monothiolated ligands suffer a strong dynamic off rate, which limits shelf life, and which can be displaced rapidly in vivo by biothiols such as glutathione. The latter issues can be ameliorated using multidentate thiol groups [24, 31]. Carbon allotropes such as carbon nanotubes and graphene have similar requirements although colloidal stability is usually provided by direct chemical or plasma modification of the surface to display hydroxyl and carboxyl groups [32]. Overall, the choice of which NP surface chemistry to utilize is primarily application driven, since as just highlighted, each approach is defined by both benefits and liabilities that must be balanced.

Bioconjugation

For most biological applications, NPs are further modified with some type of biomolecule; these span proteins, peptides, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, drugs, and lipids [24, 33]. The biomolecules are meant to provide wide-reaching features, such as cell/tissue targeting, improved cellular uptake, and antigen presentation in the case of vaccine development. These capabilities are accomplished through either heterogeneous or homogeneous bioconjugation chemistry, with the latter being the most desirable. In-depth discussion can be found in other reviews [24, 34, 35]. Heterogeneous chemistry such as carbodiimide (EDC) linkage targets the ubiquitous groups on proteins such as amines or carboxyls, for example, and will result in a NP-bioconjugate where the proteins have multiple different orientations, mixed avidity, and different ratios per NP. These parameters of NP-protein conjugation could provide a lever to improve upon the efficacy of existing vaccines containing protein antigens. In contrast, homogeneous chemistry provides far more control over variables such as ratio of biomolecule per NP, relative orientation, attachment strength, and linkage or separation distance [36]. These characteristics can all be important for immunological applications, where the combination and density of antigens or stimulatory cues determine the nature of immune response. Bioorthogonal chemistries seek site-specific chemical attachment of biomolecules without disturbing any of the native functional groups; this ability could enable targeting, for example, while maintaining the immunological function of a vaccine or immunotherapy. Toward these goals, non-natural chemical functional groups such as azides and alkynes are being exploited [37]. Controlling the ratio of biomolecules attached to a given NP could be an important parameter in many vaccine applications that involved antigen-priming. For example, attaching a single biomolecule or similarly low densities to a NP may result in conjugates displaying a Poisson distribution centered around the average value that could impact utility by introducing variability in the response. In contrast, attempting to add very large numbers may perturb the NP’s colloidal stability, which could also impact accessibility of immune cells to antigens.

Characterization

Following on directly from both the NP preparation and subsequent bioconjugation, it is imperative to collect as much information as possible on the material’s physicochemical characteristics as these features directly impact function. More importantly, this understanding can allow a direct correlation between performance and NM properties. The number of potential interactions and pathways that can be present in an immunological context, along with concentration and avidity-specific effects, make this endeavor even more critical. NP-bioconjugate variables that are commonly interrogated include NP polydispersity, size, hydrodynamic diameter, stability, average number of biomolecules attached, biomolecular orientation, and the effective binding constants. A key challenge, however, is that very few analytical techniques exist that can provide such detailed information. Those that do exist often provide either indirect data or data averaged over the ensemble (e.g., dynamic light scattering) [38]. Thus, characterization is usually an amalgam of several indirect techniques, along with interpretation of functional results. A related area of characterization is NP toxicity. These concerns arise from the presence of materials such as Cd, in the case of QDs, along with a lack of understanding of how nanoscale size and architecture influences biological interactions. For example, is a material previously considered inert, such as gold or silicon, potentially problematic in a NM format [39–41]. Given the desire to utilize NMs for very specific and targeted utility in the immune system, any off-target, long-term toxicity, or unplanned side effects could be amplified if these changes alter the types of immune cells that are generated, which in some cases can circulate for decades.

Nanoparticle Interfacial Phenomena

Since inorganic NP bioconjugates and their application in targeted medical applications represent a relatively new area of research and development, it is important to point out that many aspects of how these composite materials function in both a nano- and macroscale environment remain largely unknown. NP physicochemical properties rarely conform exactly to predictions from models or simulations [27]. This issue, in turn, directly impacts the ability to design such composite materials or make predictions about how they will function in the complex environment(s) of an immune system. Some of the phenomena that such materials experience are slowly being elucidated through systematic investigation. In seminal work, Zobel and colleagues confirmed that NPs structure their surrounding environment regardless of whether the environment is organic or aqueous, and that this structure can extend to almost twice the NPs diameter [42]. Such structuring is believed to cause and strongly influence complex phenomena that occur at the NP-bulk interface including localized variation in pH, pKa, density, and the presence of ionic gradients along with boundary zones. An eventual understanding of these phenomena may help clarify some of the unexplained interactions that have been observed with NPs and their bioconjugates. For example, it appears that the activity of an enzyme can be enhanced when attached to a NP. Examples includes enzymes acting on NPs displaying a substrate or NPs displaying the enzymes themselves. Preliminary mechanistic studies suggest these enhancements result from high, localized avidity for enzyme acting on NP-substrate along with alleviation of rate-limiting steps for NPs displaying enzymes: the latter presumably arises from the many changes that occur in the structured environment [43, 44]. It is currently unclear how these same types of phenomena will affect the intended function of an immune-targeted NP-bioconjugate and how this must be accounted for in the design process.

The corona formation that arises once a NP-bioconjugate is transferred to a biological environment, taken up by a cell, or is introduced in vivo is also expected to play a critically determining role within most immune applications. This process is characterized by the rapid binding of proteins and other biomolecules to the NP surface which creates a surrounding corona. Formation of this corona is characterized by a continuous dynamic process whereby lower concentration species with higher affinity replace higher concentration species with lower affinity [45, 46]. The corona is influenced by the type and character of the NP materials themselves and will obscure molecules on the NP surface, thus potentially affecting in vivo function, along with altering distribution, excretion, long-term fate, and toxicity profiles. The limited understanding of the protein corona phenomenon and how it alters downstream immunological effects still hinders NP translation attempts, such as vaccine development.

Of course, the above overview is a simplification of all the considerations that go into the use of an inorganic NM or NP for a given biological application. What this summary does reflect, however, is that use of NMs within the context of biology, let alone an immunological focus, is not a plug-and-play process; concerted thought is required in both designing experiments and analyzing data. It is not always a given that what worked in one model system can be readily transferred to another system, as there is heterogeneity of immune responses across tissues, diseases, and species. Similarly, immune responses develop differently even across patients with the same disease [47]. Additionally, summarizing the above points, consideration must be given to the type of inorganic NM, its size and shape, what the surface chemistry is, what biomolecules are attached to the surface, how it is made colloidally stable, potential toxicity concerns, and ultimately, how it is applied [24]. In the next section we summarize some of these inorganic NMs which could ultimately help guide which of the parameters just listed should be manipulated for specific applications.

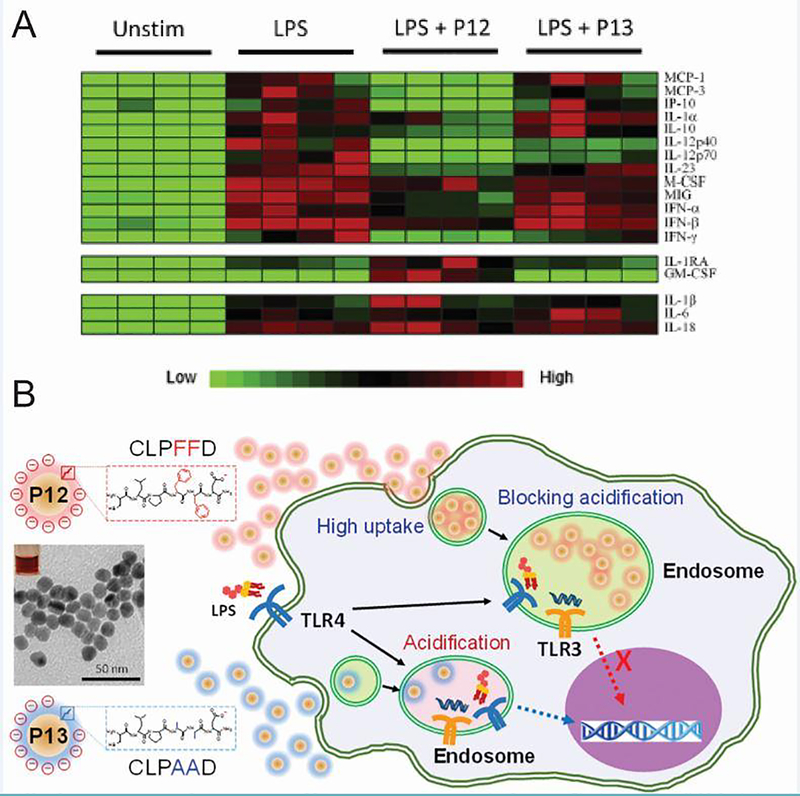

Physicochemical properties of inorganic materials impact intrinsic immunomodulatory activity

As the previous section demonstrates, the physicochemical properties of inorganic NMs play an important role in the interaction with biological molecules. This is true to an even greater extent for vaccines and immunotherapies because studies in the last decade reveal that many inorganic NMs themselves can induce inflammatory or tolerizing immunological effects. Not surprisingly then, a new focus is elucidating the mechanisms behind intrinsic immunomodulatory properties of inorganic NMs such as AuNPs [48, 49], QDs [50, 51], silver NPs [52], iron oxide NMs [53, 54], titanium dioxide NPs [52, 55], and others. The effects of factors such as NM size, shape, charge, and surface functionalization in promoting or inhibiting immune function is the focus of this section and a representative list is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inorganic NMs can promote inflammation or tolerance in the absence of other immune signals.

| Immune Setting | Inorganic NM | Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic immunogenicity | AuNPs | Blocked IL-1β-induced activation | 48 |

| Inhibition of TLR9 signaling in macrophages was dependent on NP size | 57 | ||

| Increased hydrophobicity correlated with increased gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines | 49 | ||

| Semiconductor QDs | Modulated NF-κB inflammatory pathway |

50 51 |

|

| Multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) | Mimicked response due to TLR agonists | 67 | |

| Induced macrophage activation by a calcium-dependent signaling cascade | 68 | ||

| Increase antigen-specific killing ability | 70 | ||

| Graphene QDs | Induced apoptosis by NF-κB pathway and autophagy by p38 MAPK pathway | 71 | |

| Polarized T cells towards TH2 phenotype | 72 | ||

| Silica NPs | Particle size, charge, and hydrophobicity impacted immunogenicity | 75 | |

| Induced antigen-specific T cell and antibody responses | 76 | ||

| Surface modification with carboxyl groups suppressed cytokine suppression in vitro and in vivo | 77 | ||

| Surface functionalization with amino or phosphate groups attenuated immune cell infiltration, TH2 cell polarization, and type 2 macrophage differentiation in an allergic airway inflammation model. | 78 | ||

| Particle size and charge impacted uptake and inflammatory cytokine secretion | 79 |

Gold Nanoparticles

Gold has been used in modern medicine since the 1920’s when it became a common treatment for tuberculosis [56]. At this time, it was thought that the bacterium responsible for tuberculosis also caused rheumatoid arthritis (RA). While gold therapy was ultimately ineffective for treating tuberculosis, it was very successful in reducing inflammation in RA. More recently, gold has been used in other applications such as cancer, and as an antimicrobial agent, typically in nanoparticulate form. AuNPs can range in size from 1 nm to >100 nm and have strong optical absorption and light scattering due to localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [34]. This optical phenomenon occurs when light interacts with conductive NPs that have a diameter smaller than the incident wavelength. Resonance can be tuned by altering the aspect ratio of gold NMs in the form of gold NRs (AuNRs). These features make AuNPs desirable for imaging applications and photothermal therapy. Additionally, they can be conjugated with a wide variety of biomolecules such as immune signals.

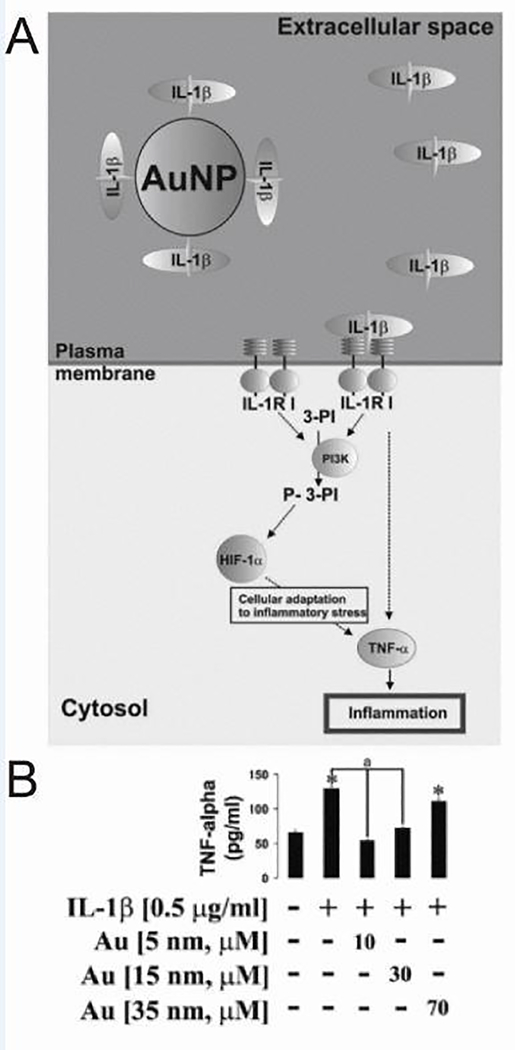

Despite its long-term use, the use of AuNPs to directly modulate immune response is relatively recent, and the mechanism is still unclear. For example, one study probed the effectiveness of gold in treating inflammatory diseases that are dependent on IL-1β, a pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with inflammation, pain, and autoimmunity [48]. Citrate-stabilized AuNPs measuring 5, 15, 20, and 35 nm in diameter were incubated with THP-1 human myeloid leukemia cells because they express numerous IL-1β receptors per cell (Figure 3A). Treatment with 5 nm particles specifically blocked activation induced by IL-1β. Since larger NPs did not have the same result on activation, size effects were further probed by normalizing overall surface area of the AuNPs, irrespective of the diameter of the particles used to treat. Interestingly, this approach revealed that activation – as indicated by production of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α) – decreased with decreasing NP size, suggesting that the anti-inflammatory activity is related to the ability of AuNPs to interact with extracellular IL-1β (Figure 3B). AuNP size has also been implicated in other important immunological processes. As one illustration, size impacts the ability of NPs to blunt inflammatory TLR9 signaling [57] in macrophages.

Figure 3.

AuNPs blocked IL-1β-induced cell activation. A) AuNPs inhibited the cellular inflammatory response by selectively blocking the IL-1β-dependent pathway. B) When THP-1 cells were treated with IL-1β and AuNPs, it was determined that the inhibition of TNF-α secretion was dependent on AuNP size. (*p < 0.01 vs control) Adapted with permission from [48], copyright © 2013 WILEY‐ VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

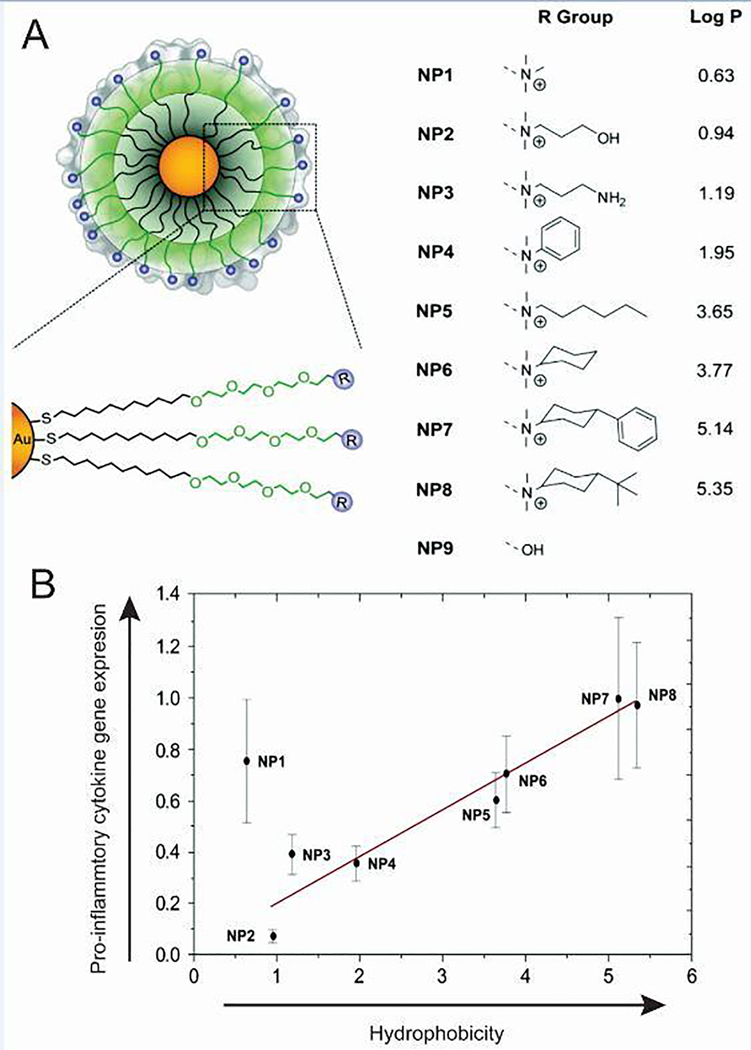

Using a systematic approach, the effect of hydrophobicity on immune response was also recently analyzed by developing AuNPs functionalized to display different surface groups [49]. Importantly, a spacer was employed to remove background effects and specifically isolate the effects of the increasingly hydrophobic groups. The immune response to eight different functionalized NPs, with a core size of 2 nm, was investigated by treating splenocytes isolated from mice and quantifying mRNA expression by qRT-PCR (Figure 4A). Interestingly, a correlation was found between increasing hydrophobicity and increased expression of a number of pro-inflammatory genes including TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ (Figure 4B). Understanding the robustness of such correlations is functional settings is an crucial next step for the immune engineering field. Even so, this work reveals important fundamental information about activation of the innate immune response, as several lines of research suggest hydrophobicity may be a simple danger-associated molecular pattern because hydrophobic regions of the cell membrane are exposed during necrosis or protein denaturation [58].

Figure 4.

Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression was dependent on AuNP surface charge. A) AuNP surfaces modified with surface groups of increasing hydrophobicity. B) A 2 hour incubation of AuNPs with increasing hydrophobicity resulted in increased in vitro gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α. Adapted with permission from D.F. Moyano, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 134 (2012) 3965–3967 [49]. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

Quantum Dots

Luminescent QDs are nanocrystals typically consisting of binary combinations of II-IV or II-V semiconductors with radii that are usually found in the 2–10 nm range. The nanoscale size of QDs gives rise to discrete energy bandgaps that allow tuning of photoluminescence as a function of diameter from the visible to the near infrared. This ability, along with high multiphoton action cross-section, photostability, and strong resistance to degradation makes QDs attractive as fluorescent probes for multiplexed analysis, energy transfer techniques, and deep-tissue imaging agents. In addition, their non-trivial surface area allows QD to simultaneously serve as a scaffold for conjugation with multiple classes of biomolecules. Details on preparation, bioconjugation, and general biological applications are detailed in several reviews [35, 59–63].

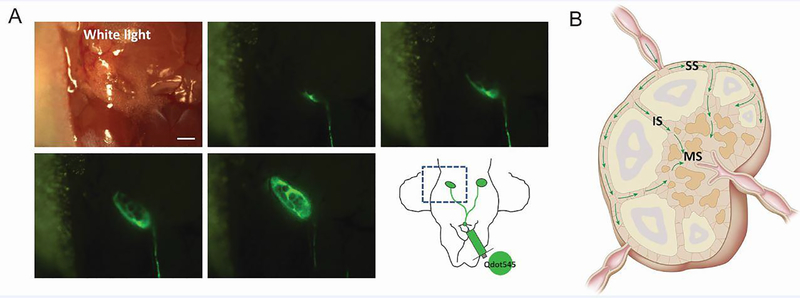

In the context of immune tissue, the properties of QDs just mentioned have been exploited for real-time imaging of flow through lymphatics and into LNs of mice [64]. This is important information to gather, as lymphatic drainage is a primary route that antigens travel through to reach LNs, tissues at which adaptive immune responses against antigens are generated. CdSe/ZnS core/shell QDs were tracked by fluorescence microscopy, allowing rapid visualization of flow through the cervical lymphatics into the cervical LNs (Figure 5A). This approach provided spatial information that revealed QDs flowed first around the edges of the node through the subcapsular sinuses, then flowed through the intermediate sinus into the medullary sinus (Figure 5B). These types of studies could help reveal distinct locations in which specific classes of antigens localized, which could help predict or characterize development of inflammatory or tolerogenic response for new therapies.

Figure 5.

QDs as a tool to visualize lymph flow. A) Interstitial injection of QDs at the chin allowed rapid visualization of lymph flow through cervical lymphatics into cervical LNs of mice. B) QDs flowed first through the subcapsular sinuses, then the intermediate sinus and into the medullary sinus. Adapted with permission from [64].

Another study investigated the immunological impact of QDs on human epidermal keratinocytes and human dermal fibroblasts [50]. Skin cells are considered one of the first lines of defense in the immune system and one possible route of exposure to QDs. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that internalization of the 15 nm CdSe/ZnS-COOH nanocrystals by either cell line increased with concentration and exposure time. Analysis of 84 genes associated with the innate and adaptive immune systems revealed that many of the genes impacted by QD treatment were linked to the NF-κB pathway, which plays an important role in inflammation. A decrease in nuclear NF-κB over time was also seen, indicating that QDs may alter pathways associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, or apoptosis.

Carbon Nanomaterials

Numerous NMs, such as CNTs, can be derived from carbon allotropes [34]. For example, single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) are a single sheet of roll graphene, and multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) are composed of multiple sheets of graphene rolled concentrically. Additionally, these materials can be metallic or semiconducting, as in the case of graphene QDs. The electronic and optical properties, as well as the large surface-to-volume ratio of CNTs make them attractive for biological applications. Important to note is that CNTs are hydrophobic, meaning that functionalization is typically required before use in these applications. Carbon NMs offer specific advantages for immunotherapy such as flexible surface chemistry and enhanced internalization by cells [65]. Additionally, as mentioned, hydrophobicity may be a key driver of intrinsic immune function in the context of NM design, so CNTs may offer unique opportunities in this area. As they are increasingly used in research, it is important to understand both desirable and undesirable effects they may have on the immune system [66]. These effects can, in part, be attributed to material characteristics of CNTs. Below we discuss relevant factors including length, charge, and surface functionalization.

Whole genome expression was one recent approach to begin understanding the complex interactions between CNTs and the immune system [67]. MWCNTs of two different sizes (20 – 30 nm diameter or 9.5 nm diameter) were either oxidized, or oxidized and modified with ammonium. Treatment of T cells or monocytes with any of the four types of CNTs led to changes in genes associated with a range of pathways, including those related to DC maturation, NF-κB signaling, and TH1 chemokine secretion. Interestingly, each treatment had a different effect on gene expression, with no single gene being affected by all four types of CNTs studied. MWCNTs that were modified with ammonium had very little effect on gene expression in T cells compared to those that were unmodified. When analyzing cytokine secretion, however, it was seen that the surface-modified CNTs led to a much larger increase in the secretion of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. Further, this effect was enhanced with the ammonium-modified CNTs that had a smaller diameter. The changes in gene expression and cytokine secretion seen with CNT treatment mimicked those induced by pathogen interaction with toll-like receptors, meaning this class of material may be exhibit intrinsic adjuvant features that trigger pathways to generate protective responses against a pathogen when coupled or loaded with antigen.

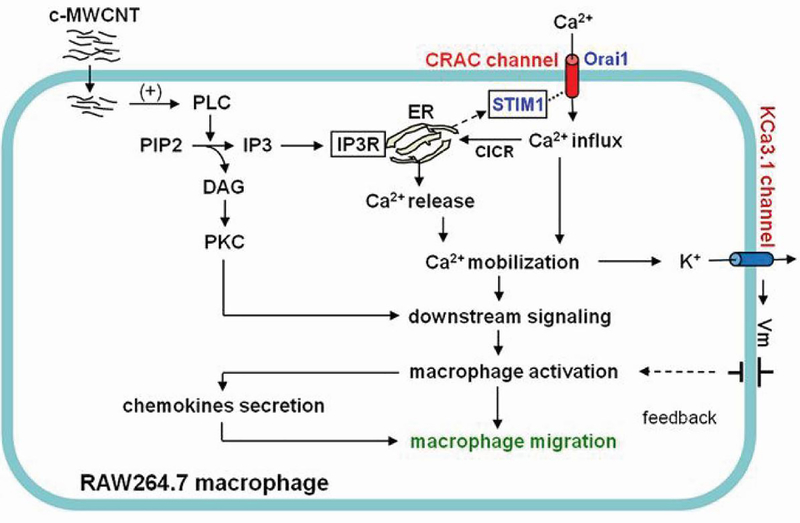

Other studies continued probing what immunological pathways surface-functionalized CNTs activate to gain further understanding of the intrinsic immunogenic features of these materials. For example, one study assessed the stimulation and migration of macrophages following treatment with carboxylated MWCNTs [68]. While quiescent RAW264.7 macrophages showed little capacity for migration in vitro, incubating the cells with CNTs led to a high level of migration, indicating they can act as a chemokine. Analysis of cells that had migrated towards the MWCNTs revealed a high level of internalization, and further led to activation. Due to recent revelations that calcium mobilization initiates immune cell activation, the impact of calcium transport inhibitors on CNT-induced activation and migration was also studied [69]. It was discovered that inhibitors significantly blunted migration, leading to the conclusion that carboxylated MWCNTs lead to macrophage activation through a calcium signaling cascade (Figure 6). These studies may shed light on specific mechanisms of the effects CNTs have on a cellular level.

Figure 6.

Carboxylated MWCNTs induced macrophage activation and migration through a calcium-dependent signaling cascade. Reprinted with permission from [68] under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

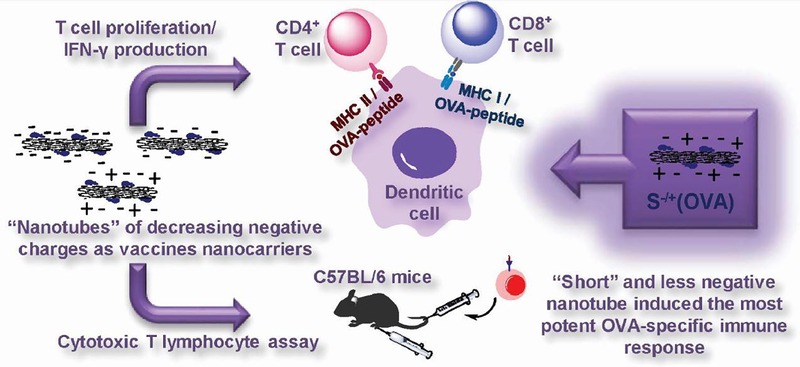

As previously mentioned, many factors are thought to influence the immunogenicity of inorganic NMs. For this reason, the impact of size and surface charge of MWCNTs on immune response is also of interest. Short (~122 nm) and long (~386 nm) CNTs that were positively or negatively charged were tested in bone marrow DCs (BMDCs) [70]. Interestingly, short MWCNTs with a negative charge (−23.4 mV) were much more readily internalized by BMDCs than long, positively charged (+5.8 mV) CNTs. The tubes were also conjugated with a model protein antigen used in immunological research, ovalbumin (OVA), to test the impact on T cells. T cells were isolated from transgenic mice expressing a T cell receptor that recognizes OVA. When BMDCs treated with OVA-MWCNTs were co-cultured with T cells, MWCNTs that were short and negatively charged increased proliferation and IFN-γ secretion, which correlated with uptake in BMDCs (Figure 7). Additionally, mice that were injected with short, negatively charged CNTs had an increased antigen-specific killing ability. This fundamental information could improve the rational design of CNT-based immunotherapies with specific emphasis on how to enhance internalization by immune cells.

Figure 7.

Cellular internalization of MWCNTs was dependent on size and surface charge, with short, negatively charged CNTs showing the highest level of uptake. When the model antigen OVA was attached, the short, negative MWCNTs resulted in the most robust T cell response in vitro and in mice. Reprinted with permission from [70], doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.030, under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CCBY).

The interaction of graphene QDs (gQDs) with macrophages was studied by focusing on two important inflammatory pathways [71]. It was first determined that increasing doses of gQDs (~3 nm) induced increasing levels of apoptosis and autophagy in cells. gQD incubation increased the activity of p38 MAPK, which responds to stress factors and inflammatory cytokines, and NF-κB, which regulates the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Inhibitors of each pathway were used to further probe the mechanisms of immunotoxicity. These studies revealed gQD-induced apoptosis was regulated by the NF-κB pathway and autophagy was regulated via the p38MAPK NF-kB pathway. Understanding the cellular pathways at play in intrinsic immunogenicity of NMs is a key aspect to the design of immunotherapies, one that only starting to gain tracking in the field.

While the previous example investigated gQDs in a macrophage cell line, it is important to probe interactions of NMs with primary human cells. In stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), non-toxic doses of gQDs inhibited proliferation [72]. The oval-shaped gQDs were 2 nm high and 23.6 ± 7.0 nm long with a surface charge of −9.4 ± 0.8 mV. The treated cells also produced less inflammatory and TH1 associated cytokines, such as IL-6 and IFN-γ, respectively. Interestingly, gQD treatment induced enhanced secretion of anti-inflammatory and TH2 associated cytokines. Additionally, while gQD treatment had little effect on immature DCs, stimulated DCs produced less TH1 and TH17 associated cytokines. When these stimulated and treated DCs were incubated with T cells, less proliferation was seen compared to control co-cultures. Intracellular cytokine staining also confirmed a polarization towards the TH2 phenotype, away from the TH1 and TH17 phenotypes. This polarization away from inflammatory phenotypes demonstrates a tolerizing effect from the gQDs. As the work above demonstrate, one of the challenges of understanding the interactions between NMs and the immune system is that the same core material often generates different responses depending on small changes in size, chemical functionality, or other features.

Silica Nanoparticles

Silica NPs, which can range in size from tens to hundreds of nanometers, are considered biocompatible and of relatively low cost. These NMs have been investigated as delivery vehicles for vaccine components because the size, surface chemistry, and morphology can be tuned during synthesis [73]. Through silane chemistry, a silica particle can be modified to include a variety of functional groups such as carboxyls, amines, or thiols. Functionalization ability and large surface area are desirable for conjugation of biomolecules. Additionally, silica NPs can be formed with pores of tunable size by manipulating reaction conditions, yielding mesoporous NPs that are specifically useful for cargo transport and release [74].

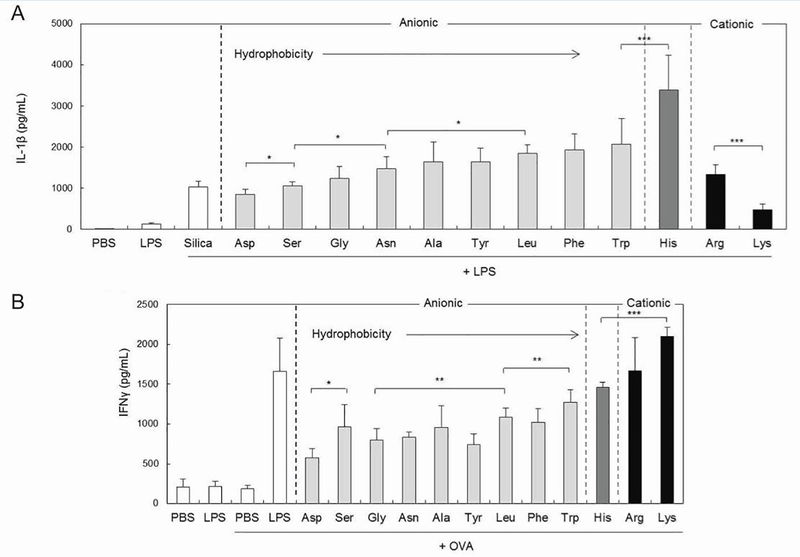

The surface characteristics of monodisperse silica NPs can also be controlled by coating the NPs with charged poly(amino acid)s (PAAs) [75]. To study the impact of surface character on immune response, N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-activated particles have been decorated by either polymerization of amino acids, or conjugation of an amino acid to the particle surface. Cytokine production was measured in response to the synergistic immunostimulatory effect of silica NPs and one of two TLR ligands. The secretion of IL-1β by mouse BMDCs was found to be correlated with both NP size and hydrophobicity. Highly hydrophobic particles coated with poly(histidine) were found to be the most immunogenic (Figure 8A) and were used to compare particles of different sizes. Interestingly, the smallest particles (300 nm) induced the highest IL-1β levels compared to 1 μm or 10 μm particles. Surface charge, which was controlled by amino acid conjugation, had no effect on immunogenicity in BMDCs. The impact of charge varied greatly when IFN-γ production levels were measured in T cells activated by treated BMDCs. In this case, cytokine secretion was enhanced as surface charge of the NPs became more cationic (Figure 8B). Like in BMDCs, more hydrophobic particles were found to be more immunogenic. Experiments such as these, that systematically control biophysical parameters of particles, provide essential information for understanding interactions with the immune system.

Figure 8.

Immunogenicity of silica NPs was dependent on size, charge, and hydrophobicity. A) Secretion of IL-1β by BMDCs treated with LPS and NPs increased with increasing hydrophobicity of amino acid groups added to the particle surface. B) When DCs pre-treated with NPs were cocultured with T cells and the model antigen OVA, IFN-γ secretion increased with increasing hydrophobicity and charge of NP surface. (*p < 0.05, **p < .01, ***p < .001) Adapted from Acta Biomater, 57, Y. Kakizawa, et al., Precise manipulation of biophysical particle parameters enables control of proinflammatory cytokine production in presence of TLR 3 and 4 ligands, 136–145, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier [75].

Rather than testing particles in conjunction with TLR agonists, other work has investigated the selfadjuvanting abilities of mesoporous silica NPs when delivered with antigen (i.e., OVA) in mice [76]. The 91 nm NPs were formed with 3.6 nm pores. When NPs were amino-functionalized, they could adsorb OVA with 2.5-fold greater efficiency than non-functionalized NPs. Mice receiving either a low dose or a high dose of OVA bound to NPs showed a strong antibody response. Interestingly, however, a much stronger antigen-specific T cell response was seen when mice were treated with the higher dose. This result suggests a threshold of antigen concentration for the development of cell-mediated immunity. Although this work demonstrated that adding amine groups to the particle surface resulted in higher antigen adsorption, it should be noted that some publications have demonstrated that the adjuvanting effects of silica NPs were actually attenuated by functionalizing the particle surface [77, 78]. Clearly there are more parameters that need to be elucidated before clinical utility can be contemplated.

In an investigation probing the impact of size on immunogenicity, hollow silica-titania core-shell NPs were synthesized with distinct sizes: 25, 50, 75, 100, and 125 nm [79]. Silica NPs were first prepared and then titanium tetraisopropoxide was added to create the titania-coated layer. Silane treatment was then used to modify these NPs with cationic (amine), anionic (carboxylate), or neutral (methyl) surface groups. Cellular uptake, toxicity, and immunogenicity were measured in mouse alveolar macrophages and human breast cancer cells. A correlation was found between increasing cell uptake and decreasing NP diameter. There was also a trend associated with surface charge, where cationic NPs were taken up more efficiently than neutral or anionic particles. The efficient internalization of positively charged NPs is widely thought to be due to interactions with negatively charged molecules of the glycocalyx membranes. Uptake, often the first step in the immune cascade, has implications in downstream signaling and ultimately the type and intensity of the resultant immune response. The impact of size and charge on the innate immune response was also tested by measuring the expression of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α by macrophages. The 50 nm particles, which were internalized most efficiently, induced the highest secretion levels of each cytokine in macrophages. Inorganic NMs are often investigated as delivery vehicles for vaccination and therapy. Further, the intrinsic immunogenicity of the inorganic NMs demonstrated in this section has been harnessed for these applications. Specifically, the next section will focus on the exploitation of the unique properties of inorganic NMs for immunization strategies aimed at infectious diseases.

Inorganic materials offer potential to improve vaccines for infectious diseases

The goal of vaccination against infectious diseases is to produce a safe, robust, antigen-specific response that protects against future exposure to the actual pathogen. While there has been great success with existing vaccine strategies, challenges still exist, including a lack of protection across a population and difficulty transporting and storing vaccines in developing regions. Inorganic NMs offer unique properties to address these challenges. While the last section focused on understanding the intrinsic features of inorganic NMs, much interest has also been devoted to coupling, loading, or formulating antigens or other immune signals to these materials to develop vaccines. This work spans an array of inorganic NMs, including gold NMs [80–82], QDs [51], silica NPs [83, 84], CNTs [85, 86], and iron oxide NPs [87] as delivery platforms for immune signals and/or as self-adjuvants in infectious disease vaccination. Some examples are summarized in Table 2 and discussed in detail below.

Table 2.

Efficacy of vaccines targeted towards infectious disease can be enhanced by inorganic NMs.

| Immune Setting | Inorganic NM | Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious disease | AuNPs | Antibody production against foot-and-mouth disease peptide was dependent on NP size | 95 |

| Delivering antigen and adjuvant reduced viral load in liver infection model | 80 | ||

| Antigen and adjuvant codelivery led to complete protection from lethal influenza challenge |

96 97 |

||

| Adjuvant delivery resulted in 100% survival in a select agent lethal challenge model |

81 99 100 |

||

| AuNMs | Surface area was correlated to cytokine and antibody production against West Nile virus envelope protein | 82 | |

| Gold nanostars served as a strong adjuvant in foot-and-mouth disease vaccination | 101 | ||

| Delivery of a DNA vaccine resulted in 100% protection from newcastle disease virus challenge | 83 | ||

| Antigen delivery resulted in strong, long-lasting antibody and cell-mediated responses against bovine viral diarrhea virus |

84 102 103 |

||

| QDs | Inhibited replication of herpes simplex virus-1 | 51 |

Gold Nanomaterials

Gold NMs have been investigated for immunotherapeutic applications in infectious diseases such as HIV [88, 89], listeria [90], parasitic diseases [91], and malaria [92]. These studies have shown promise in mouse and rabbit models, but as above, the material characteristics play a crucial role in the stimulatory responses generated by the NMs. AuNP size can be easily and precisely controlled over a large range from a few nanometers to several hundred [93, 94]. Additionally, they can be decorated with a large amount of antigen or adjuvant by simple chemistry.

Several groups have systematically tested the effect of AuNP size on response to viral proteins. For example, it was found that the antibody response to a NP-displayed foot-and-mouth disease-related peptide was dependent on particle size [95]. In a study of AuNP size effects in a codelivery system, particles ranging from 15 to 80 nm were screened for optimal delivery of OVA and an oligonucleotide that stimulates TLR9, CpG [80]. The antigen and adjuvant were directly conjugated to the particle surface through Au-S bonds. 60 nm OVA-NPs led to the highest level of antigen presentation by DCs and 80 nm CpG-NPs induced the highest expression of activation markers. Both antigen presentation and activation of DCs was necessary to induce an adaptive response, mediated by T-cells and antibodies. For this reason, DCs were incubated with a cocktail of 60 nm OVA-NPs and 80 nm CpG-NPs and injected into mice. After 48 hours, the NP-containing DCs largely accumulated in the spleen and in liver-draining LNs (Figure 9). After a robust antigen-specific T cell response to OVA was observed, the approach was next tested for protection against viral infection. Mice were immunized with DCs 5 days prior to injection of viral vectors that lead to liver infection and were engineered to express OVA. Mice immunized with AuNP cocktail-treated DCs had a significantly reduced viral load compared to control mice, or mice receiving DCs that had been incubated with free CpG and OVA. In a similar strategy, AuNPs were decorated with the matrix 2 protein from influenza A and delivered along with soluble CpG [96, 97]. This vaccination strategy led to complete protection from a lethal influenza challenge in mice, further demonstrating the utility of AuNPs as delivery vehicles for antigen and/or adjuvants.

Figure 9.

A cocktail of AuNPs found to induce APC activation and presentation accumulated in liver-draining LNs and reduced viral load in a mouse model of liver infection. Reprinted with permission from Q. Zhou, et al., ACS Nano, 10 (2016) 2678–2692 [80]. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

In another disease model, AuNPs were used as an immunization strategy to protect against Burkholderia mallei, which is classified by the CDC as a Class B Select Agent because it can be weaponized for aerosol release [81]. This bacterium, which causes the disease glanders, leads to a high mortality rate that is partially due to its expression of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an agonist to TLR4 and a strong adjuvant. Limited success has been seen in mice with LPS immunization, resulting only in partial protection, likely because LPS induces T cell-independent immune responses that do not result in long-term immunity [89]. In an attempt to improve this effort, LPS was conjugated to a protein carrier and covalently coupled to the surface of 15 nm AuNPs [81]. Immunized mice produced significantly enhanced IgG and IgM responses compared to control groups. Nano-glycoconjugates were synthesized with one of three protein carriers and all improved survival in a mouse challenge model of glanders compared to LPS treatments alone. In a Rhesus macaques model, slightly increased protection was seen in vaccinated animals, but the difference in overall survival was not significant [99]. For this reason, the vaccine was resynthesized by first screening an array of antigens by simulation to determine factors such as adhesive properties and interaction with MHC I and II [100]. Impressively, when two proteins identified by this method were incorporated into the nano-glycoconjugate vaccine, 100% survival was observed in Rhesus macaques following a lethal challenge of glanders. This series of studies underscores the importance of rational design in vaccine applications.

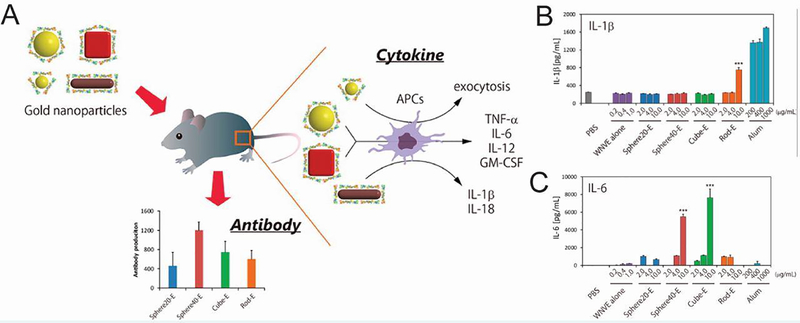

Both studies above demonstrated the conjugation of an adjuvant to AuNPs, but as the previous section discussed, AuNPs themselves can induce immune responses, allowing them to serve as the adjuvant in vaccination strategies. One study tested gold NMs as a self-adjuvanting delivery system and vaccine [82]. As previously discussed, biophysical parameters impact the degree to which inorganic NMs stimulate the immune system, leading the researchers to also test the impact of size and shape on the immune response to a viral protein. Spherical, rod, and cubic NMs were developed and coated with West Nile virus envelope (WNVE) protein. Interestingly, each shape induced a different level of antibody production against WNVE in mice, with 40 nm spherical NMs causing the most significant response (Figure 10A). This did not correlate with uptake of the NMs by RAW264.7 macrophages where AuNRs were internalized most efficiently and led to the production of IL-1β (Figure 10B) and IL-18. In contrast, only the cubes and 40 nm spheres induced the secretion of other inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 (Figure 10C), and IL-12. After analyzing a number of material properties, it was found that surface area, which is related to both size and shape, was the most highly correlated with cytokine and antibody production. This study, and the work previously described using silica NPs [75], demonstrate the utility of controlling multiple particle parameters to leverage the intrinsic immunogenicity of inorganic NMs. In similar work, gold nanostars were complexed with foot-and-mouth disease virus-like particles as a vaccination strategy [101]. The gold NMs served as a strong adjuvant, promoting specific antibody production and T cell proliferation. Additionally, protection from viral infection was higher when the virus-like particles were combined with the gold nanostars rather than a conventional mineral oil adjuvant.

Figure 10.

Innate and adaptive immune responses induced by gold NMs were dependent on surface area. A) WNVE-coated gold NMs were injected into mice and the production of cytokines and antibodies was measured. B) Only AuNR incubation resulted in IL-1β production by BMDCs. C) Only cubes and 40 nm spheres induced IL-6 secretion when incubated with BMDCs. (***p < 0.001 vs control) Reprinted with permission from K. Niikura, et al., ACS Nano, 7 (2013) 3926–3938 [82]. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

Silica Nanoparticles

Due to the intrinsic immunogenicity discussed in the previous section, silica NPs have also gained the attention of researchers as a self-adjuvanting delivery system for prophylactic vaccine applications. For example, layered double hydroxide SiO2 NPs have been synthesized to deliver a DNA vaccine aimed against newcastle disease virus (NDV), which mainly affects avian species but can be transmitted to humans [83]. These 90 nm particles feature a core-shell structure, protect plasmid DNA from enzymatic degradation, and promote controlled release over 288 hours. Importantly, plasmid-containing NPs could induce a similar level of expression in human embryonic kidney cells compared to plasmid delivered with a commercial transfection agent. Serum antibody levels against NDV peaked 5 weeks post immunization in chickens. Demonstrating the impact of the NPs as an adjuvant, titers remained significantly higher through 8 weeks in mice that received the NP vaccine compared to those that received naked DNA. Additionally, at weeks 4 through 6, the immunized group also produced the highest level of lymphocyte proliferation, demonstrating enhanced immune function of T cells. Immunization of chickens with the NP vaccine resulted in 100% protection from disease challenge with no clinical signs observed, compared to 60% death with naked plasmid delivery, exemplifying the unique advantages inorganic NMs offer for improving vaccinations against viruses.

Following a previous study that demonstrated the self-adjuvanting abilities of mesoporous silica NPs delivering OVA in mice [76], similar nanovesicles were tested as an immunization strategy for bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) [84, 102, 103]. The NPs, which feature a 50 nm diameter, 6 nm wall thickness, and 16 nm pores, adsorb the viral E2 protein, which is a major immunogenic determinant of BVDV. Mice immunized with the nanovaccine elicited a 10-fold stronger antibody response compared to mice receiving the E2 protein with a strong adjuvant [84]. Importantly, the NPs also led to a strong cellmediated response that was significantly higher than the traditional vaccine control. In an attempt to address challenges associated with refrigerated storage and delivery of vaccines, the group also investigated the ability of the nanovaccine to produce long-term immune responses in mice and sheep once freeze-dried [102, 103]. Shortly after vaccination, animals treated with the freeze-dried NPs showed a robust antibody and cell-mediated response. Importantly, both responses were still detectable after 6 months. These studies took the important step of comparing a nanotechnology-based approach to a more traditional vaccine design including only an antigen and adjuvant, which demonstrated a considerable advantage. Moreover, the ability to lyophilize a nanovaccine may facilitate use in developing regions.

Quantum Dots

As discussed in the previous section, several types of QDs have been shown to affect the NF-κB pathway [43]. One group aimed to further probe this mechanism and its implication in infectious disease and cancer. NF-κB signaling inhibition was studied with aqueous synthesized QDs with emissions of 515 nm and 545 nm and corresponding radii of 2.2 nm and 2.7 nm [44]. Pretreatment of human pancreatic cancer (Panc-1) cells with either QD type significantly reduced NF-κB activation induced by TNF-α or TLR agonists. The NF-κB pathway is critical in regulating the expression of viral genes and is connected to cancer because it negatively regulates apoptosis. Accordingly, QD treatment was shown to significantly inhibit herpes simplex virus-1 induced activation of NF-κB in Panc-1 cells, which suppressed viral replication. Additionally, QD treatment promoted apoptosis in Panc-1 cells, as evidenced by both a down regulation of anti-apoptotic genes and the cleavage of proteins in the apoptotic pathway. Interestingly though, the QDs had no effect on two other signaling pathways that have implications in cancer. Unlike other studies discussed in this section, this work analyzed QDs alone, rather than as a delivery vehicle for antigen and/or adjuvant, and found significant effects in pathways related to both viruses and cancer. The following section describes inorganic NM-based approaches with a similar goal to vaccination against infectious diseases: the generation of a robust inflammatory immune response. These strategies, however, are aimed at developing specific antibodies and T cells capable of fighting cancer.

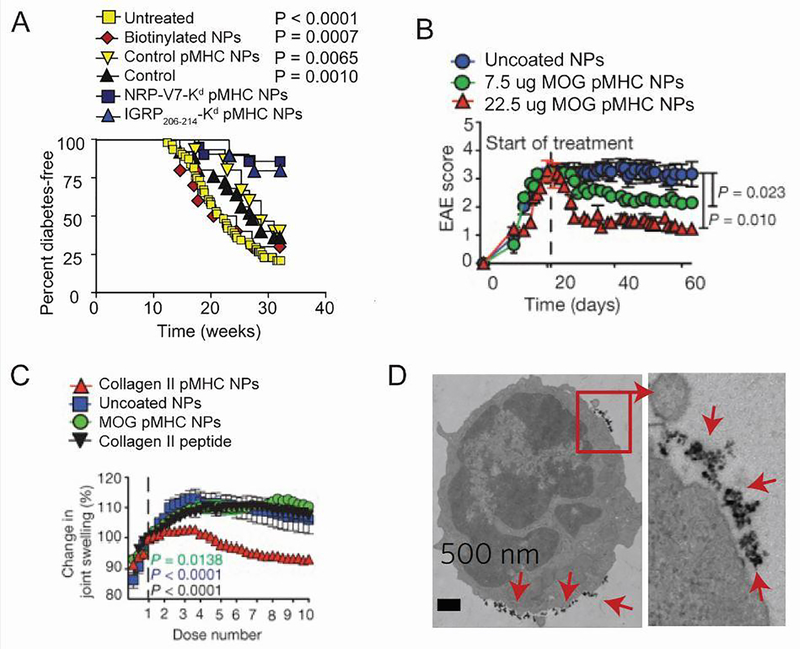

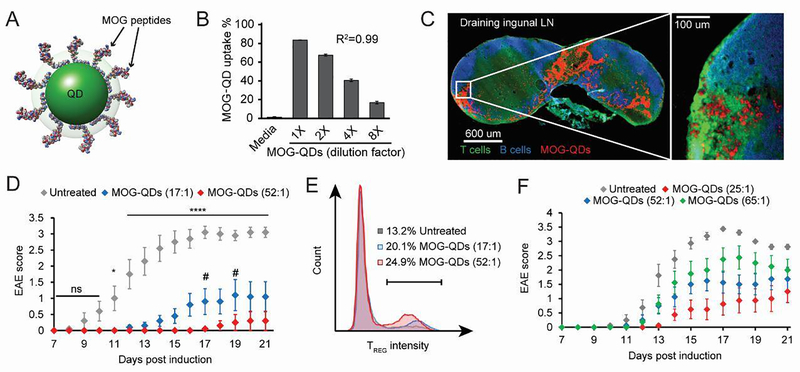

Cancer immunotherapies can be enhanced by formulation with inorganic NMs

A major challenge in cancer is the immunosuppressive environment that surrounds tumors and limits the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack cancer cells. Development of better immunotherapies is further hindered by differences across patients and cancers, as well as ongoing tumor mutations. The current treatment methods of chemotherapy and radiation are non-specific and highly toxic to healthy tissues. The goals of emerging cancer immunotherapies are similar to those of infectious disease vaccination in that the desired outcome is a strong, tumor-specific response. Of specific importance is the development of a robust T cell response [104, 105]. One recent transformative development in this field is checkpoint blockade therapy. Checkpoints normally guard against the development of autoimmune reactions but can be upregulated in the tumor microenvironment, preventing immune cells from reaching and destroying the tumor. New therapies aim to block these inhibitory immune pathways to produce a robust anti-tumor immune response. A second example is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells that are isolated from a cancer patient, engineered ex vivo to specifically recognize the patient’s tumor antigens, then infused back into the patient where they seek out and destroy cancer cells [23, 106, 107]. Despite these recent advances, many challenges still face the field of cancer immunotherapy, for example, CAR T cell therapy’s efficacy is highly dependent on the type of cancer being treated. Inorganic NMs present an interesting opportunity to address some of the challenges facing cancer immunotherapy because they can be ablated to destroy established tumors, decorated with both cancer antigens and molecules that stimulate the innate immune system, and serve as an imaging modality with potential for theranostic development [108]. Table 3 summarizes key examples detailed in this section.

Table 3.

Unique features of inorganic NMs can be leveraged to enhance anti-tumor immunity.

| Immune Setting | Inorganic NM | Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | QDs | Promoted apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cell line | 51 |

| AuNPs | Antigen-decoration delayed, reduced, or inhibited tumor growth in B16F10, B16-OVA and 4T1 cancer models. Efficacy in E.G7-OVA model was dependent on NP size. |

111 113 116 118 |

|

| Efficacy in B16-OVA cancer model was dependent on adjuvant choice for immune signal coating and injection route |

119 120 |

||

| poly(propylene sulfide) (PPS) NPs | Antigen and adjuvant delivery delayed EG.7-OVA tumor growth | 114 | |

| SWCNTs | Adjuvant attachment improved inhibition of cancer cell migration | 115 | |

| Antibody-coating targeted intratumor but not peripheral TREGs | 122 | ||

| Taken up by monocytes, entered tumor interstitium, and crossed blood vessel walls. | 125 | ||

| Ablation resulted in strong local and systemic anti-tumor response with memory | 131 | ||

| AuNRs | Combined irradiation and adjuvant delivery promoted protection from B16F10 tumors | 133 | |

| Silica NPs | Codelivery of OVA and CpG reduced B16-OVA tumor growth and suppressed tumor development following rechallenge. | 134 | |

| Cationic nature promotes tumor cell death and adjuvant delivery activates anti-tumor immune cell response | 135 | ||

| Iron oxide NPs | Magnetic targeting of IFN-γ coated NPs destroyed tumors | 136 | |

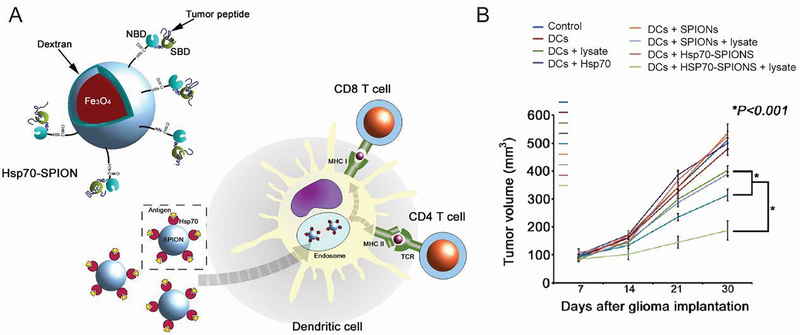

| DCs containing tumor lysates and heat shock protein-coated NPs increased survival in glioma model | 138 | ||

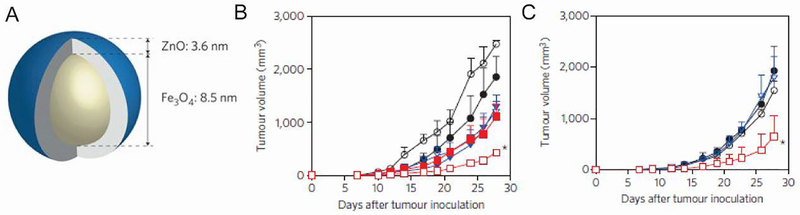

| Iron oxide-zinc oxide NPs | DCs containing antigen-coated NPs increased survival in CEA cancer model | 140 |

Gold Nanoparticles

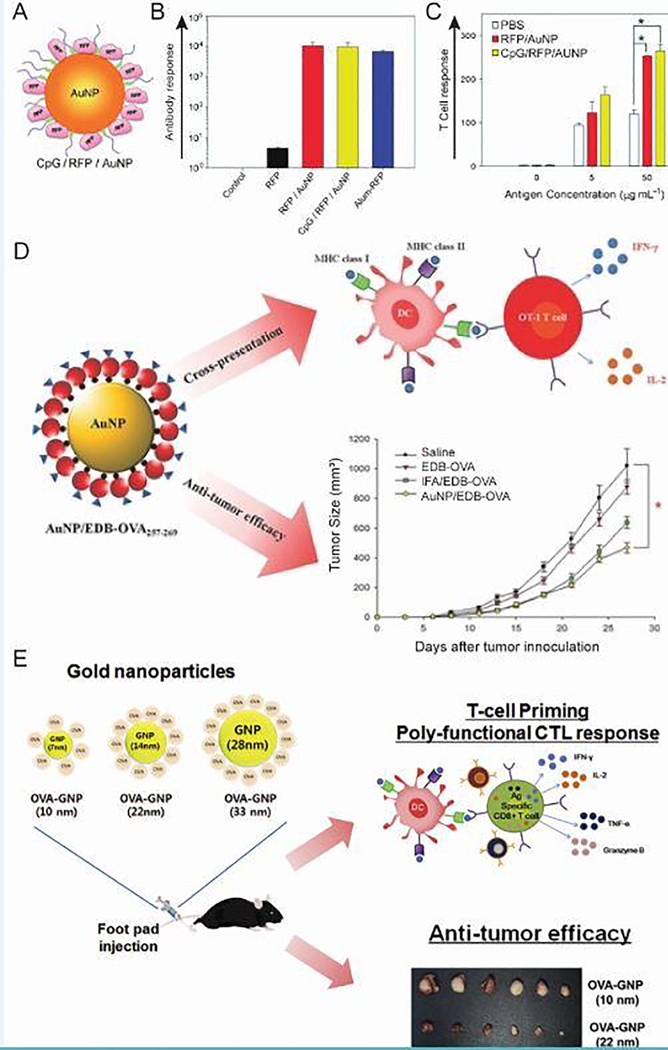

AuNPs have been heavily researched in cancer applications because they can deliver cancer antigens [109] and adjuvants [110], can be imaged in vivo [111], and can be used for thermal destruction of tumors (“ablation”) [112]. In a model antigen study, AuNPs were coated with red fluorescent protein (RFP) and CpG as a cancer vaccination strategy (Figure 11A) [111]. RFP was attached through an Au-S bond and thiol-modified CpG with a ten-adenine spacer was attached to form 20 nm particles. Interestingly, immunization of mice with coated AuNPs elicited RFP-specific antibody (Figure 11B) and T cell (Figure 11C) responses regardless of the inclusion of CpG, indicating a self-adjuvanting ability of the particles. In a melanoma model of cancer involving B16F10 tumor cells that express RFP, tumor growth in mice was delayed for up to 4 weeks for both groups. Another study reported similar results when codelivering OVA-AuNPs and CpG-AuNPs [113]. OVA-coated NPs alone were sufficient for inhibiting growth of B16 tumors that express OVA and the addition of CpG-AuNPs did not enhance this effect. Researchers that tested the delivery of OVA and CpG on PPS NPs, however, reported that the CpG coated NPs were necessary to delay tumor growth in a challenge with the E.G7-OVA thymoma cell line [114]. Additionally, injection of CpG into glioblastomas showed promise in mice, and binding CpG to SWCNTs resulted in decreased migration of glioblastoma cell lines [115]. The differences in these results further underscore the importance of understanding the reaction of an inorganic NM delivery system with the immune system when developing immunotherapy strategies for a cancer, a disease which varies greatly across subtypes and patient populations.

Figure 11.

AuNPs as a self-adjuvanting delivery system for antigens in multiple cancer models. A) AuNPs coated with model antigen RFP and CpG. B) Antibody production following immunization of mice was measured and revealed a robust response regardless of the inclusion of CpG. C) T cells isolated from mice immunized with RFP/AuNPs or CpG/RFP/AuNPs responded to restimulation with RFP. D) Conjugation of a cancer antigen to OVA on AuNPs promoted cross presentation and resulted in a reduction in tumor growth. E) Cytotoxic T cell response and subsequent efficacy in cancer models depended on AuNP size. (*p < 0.05 between two groups) Adapted with permission from [111] Copyright © 2012 WILEY‐ VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, [116] © 2014 WILEY‐ VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, and Journal of Controlled Release, 256, S. Kang et al., Effects of gold nanoparticle-based vaccine size on lymph node delivery and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses, 56–67 [118], Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.

The AuNP platform was next evaluated in the 4T1 breast cancer model, where tumor cells highly express the extra domain B (EDB) of fibronectin [116]. This model is more relevant to human cancer because it results in spontaneous metastasis to sites affected in breast cancer, including the draining lymph nodes, lungs, and bone. Previous work demonstrated that EDB-targeted vaccination of mice resulted in a robust antibody, but did not show the cell-mediated response necessary for tumor eradication [117]. It was hypothesized that the self-adjuvanting ability of AuNPs could promote a T cell response directed specifically at the tumor-associated antigen. By adding OVA to the C-terminus of EDB and two cysteine residues to the N-terminus, the protein could bind to AuNP surfaces (Figure 11D). Exogenous antigens are typically presented by APCs in MHC II, but the inclusion of OVA promoted cross presentation, a process where antigen is also displayed on MHC I. Presentation of MHC I-displayed antigen to CD8+ T cells allows the development of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells. In addition, NP treatment of mice with established 4T1 tumors significantly reduced growth, a critical experiment for determining translation potential of cancer immunotherapies due to the unlikeliness of patients receiving prophylactic tumor vaccinations.

Further studies aimed to elucidate the effect of AuNP size on delivery to LNs, where a response against cancer antigens can develop, and the subsequent T cell response (Figure 11E) [118]. In vitro, there was a trend associated with increasing size of OVA coated NPs and increases in DC uptake, DC activation, and inflammatory cytokine secretion by T cells, all important steps in the development of robust anti-tumor immunogenicity. Following injection in mice, greater uptake was seen in draining LN-resident DCs for 22 nm and 33 nm particles compared to the smallest 10 nm NPs. This uptake was directly correlated with an enhanced CD8+ T cell response, an important consideration in cancer therapeutics, as this cell type can directly kill cancer cells. Next, prophylactic OVA-AuNP injection was tested as a strategy to slow or prevent the growth of tumors in the E.G7-OVA thymoma cancer model. The effect of size on immunogenicity translated to this model where the larger NPs significantly slowed tumor growth, but the smaller NPs had no significant effect. This series of studies showed the efficacy of an AuNP delivery system in multiple models of cancer and underlines the importance of understanding parameters such as particle size in initial steps of the immunological cascade and the ultimate therapeutic outcome.

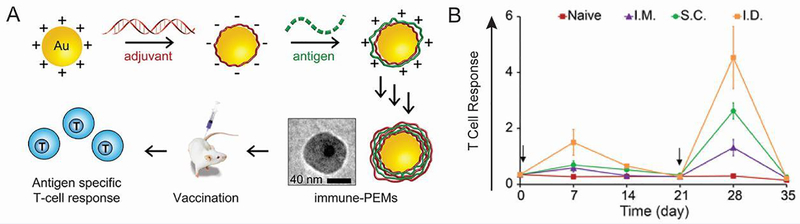

Another AuNP immunization strategy involves coating them with polyelectrolyte multilayers composed entirely of immune signals (iPEMs) [119]. The positively charged antigen (OVA peptide) and negatively charged adjuvant (TLR3 agonist) can be alternatingly deposited onto the particle surface as a method of codelivery (Figure 12A). Each bilayer added approximately 10 nm to the NP diameter to a final size of 43.5 nm after four bilayers. iPEM-coated AuNPs treatment induced both activation and antigen presentation in DCs. Additionally, injection of the NPs in mice produced a strong antigen-specific T cell response. To gain more insight into the mechanism, the impact of injection route, immune signal dose, and adjuvant choice on the T cell response was assessed [120]. Interestingly, intradermal injection produced the most robust response, followed by subcutaneous and intramuscular injections (Figure 12B). This result could be important for clinical translation of NP-based therapies as intramuscular is the most commonly used injection route in vaccination, but in these studies this route produced the weakest response. The intradermal route is particularly intriguing because of the existence of skin-specific DCs known as Langerhans which could potentially phagocytose vaccine antigens [121]. In a mouse model of melanoma where B16 tumor cells express OVA, the adjuvanting abilities of TLR9 agonist CpG were compared to polyIC, a synthetic analog of viral double stranded RNA that interacts with TLR3. While iPEMs consisting of OVA peptide and polyIC delayed tumor growth, those containing CpG had a more robust effect resulting in 50% survival, compared to 0% in untreated mice. The rational design of future cancer immunotherapies will require answering such fundamental questions as what the best route is for injection and what the most effective adjuvant is.

Figure 12.

Immune signal-coated NPs produced a robust immune response. A) AuNPs coated with alternatingly deposited antigen and adjuvant induced an antigen-specific T cell response in mice. B) The intradermal injection route produced the highest frequency of antigen-specific T cells following a prime on day 0 and boost on day 21. Adapted with permission from [119] and [120].

Carbon Nanomaterials

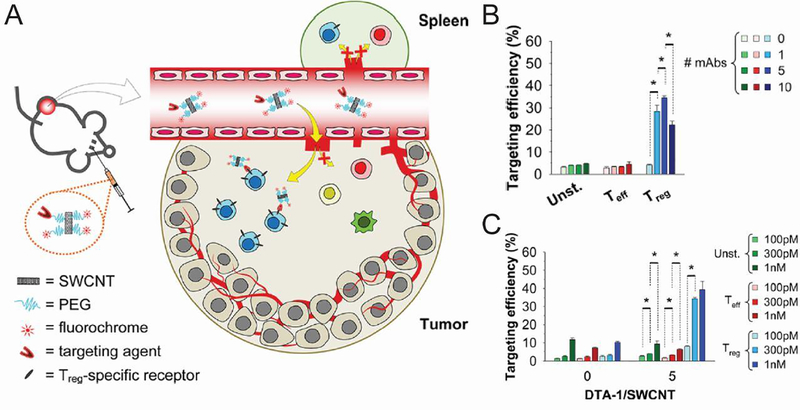

TREGS have been increasingly implicated in cancer because tumors exploit these cells to actively suppress the immune responses the body is mounting against the tumor. NMs offer an opportunity to target and potentially destroy this cell population. One group aimed to target intratumoral TREGS, but not peripheral TREGS, through delivery of SWCNTs (Figure 13A) [122]. The first experiment assessed the expression of a number of markers on TREGS and effector T cells. Because glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related receptor (GITR) displayed the highest expression on intratumoral TREGS, an anti-GITR mAb was chosen as the targeting agent. Optimal targeting efficiency and selectivity in a culture of splenocytes was found to occur when the 101 nm-length SWCNTs were each decorated with 5 antibodies (Figure 13B). It was also determined that almost maximum internalization in vitro occurred after just 1 hour, with only a small increase occurring if SWCNTs were incubated with cells for an additional 5 hours. When the concentration of SWCNTs incubated with splenocytes was increased from 100 pM to 300 pM it resulted in better efficiency and selectivity of TREG targeting (Figure 13C). Interestingly, if the concentration was further increased to 1 nM, the trend did not continue. In B16 tumor-bearing mice, the GITR-decorated tubes were targeted to TREGS in the tumor with 3-fold higher efficiency than to splenic TREGS, indicating the strategy’s specificity.

Figure 13.

GITR-decorated CNTs specifically targeted intratumor TREGS. A) A combination of passive and active targeting resulted in efficient and selective targeting of intratumoral TREGS by SWCNTs coated with a ligand against known TREG-specific receptors. Splenocytes isolated from transgenic mice with fluorescent TREGs were treated with fluorescently-labelled SWCNTs decorated with varying numbers of GITR antibody (B) or with varying concentration of fluorescently-labelled SWCNTs (C). Targeting efficiency, as measured by flow cytometry, was maximal when SWCNTs contained 5 antibodies and increasing concentration of SWCNTs resulted in increased efficiency. (* 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05) Reprinted with permission from C. Sacchetti, et al., Bioconj. Chem., 24 (2013) 852–858. [122]. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

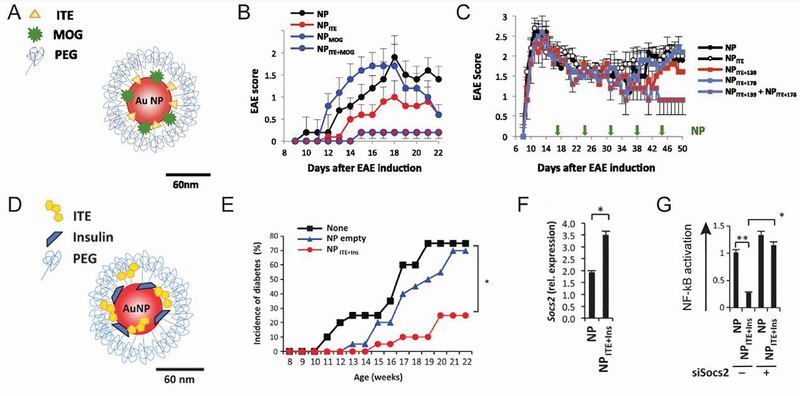

Past studies have shown that SWCNTs are one of the most efficiently delivered NMs in tumor applications, but little focus has been put on understanding the method of tumor targeting [123, 124]. Following an initial publication demonstrating that SWCNTs can accumulate in the tumor via both active and passive targeting mechanisms, additional factors were assessed [125]. Mice were first injected with tumor cells, followed 10 days later by i.v. injection of SWCNTs with a diameter around 1 nm and lengths between 100 and 300 nm. After mixing the tubes with Cy5.5-NHS and sulphosuccinimidyl 4-N-maleimidomethyl cyclohexane-1-carboxylate to enable imaging and peptide binding, these NMs were found to be taken up by circulating blood cells. The cells then entered the tumor interstitium and appeared to cross through blood vessel walls. Interestingly, when the tubes were reacted with a thiolated peptide sequence (RGD) known to target integrin receptors on angiogenic tumor blood vessels or an irrelevant peptide (RAD), no differences were seen in tumor accumulation for up to 7 days. After this time, RGD-SWCNTs were retained while RAD-SWCNTs were more readily cleared, suggesting that targeting moieties can be more or less effective depending on the time point when uptake is analyzed. Overall, a better understanding of how inorganic NMs can successfully target tumors could improve selectivity and decrease systemic toxicity associated with chemotherapy.