Abstract

We argue that enhanced Traffic Control Bundling (eTCB) can interrupt the community-hospital-community transmission cycle, thereby limiting COVID-19’s impact. Enhanced TCB is an expansion of the traditional TCB that proved highly effective during Taiwan’s 2003 SARS outbreak. TCB’s success derived from ensuring that Health Care Workers (HCWs) and patients were protected from fomite, contact and droplet transmission within hospitals.

Although TCB proved successful during SARS, achieving a similar level of success with the COVID-19 outbreak requires adapting TCB to the unique manifestations of this new disease. These manifestations include asymptomatic infection, a hyper-affinity to ACE2 receptors resulting in high transmissibility, false negatives, and an incubation period of up to 22 days. Enhanced TCB incorporates the necessary adaptations. In particular, eTCB includes expanding the TCB transition zone to incorporate a new sector – the quarantine ward. This ward houses patients exhibiting atypical manifestations or awaiting definitive diagnosis. A second adaptation involves enhancing the checkpoint hand disinfection and gowning up with Personal Protective Equipment deployed in traditional TCB. Under eTCB, checkpoint hand disinfection and donning of face masks are now required of all visitors who seek to enter hospitals.

These enhancements ensure that transmissions by droplets, fomites and contact are disrupted both within hospitals and between hospitals and the broader community. Evidencing eTCB effectiveness is Taiwan’s success to date in containing and controlling the community-hospital-community transmission cycle.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV, Traffic control bundling, eTCB, Community-hospital-community transmission, Fomite transmission

Perspective

Repeated recent outbreaks of novel infectious diseases (e.g. H1N1 pdm09, SARS, MERS, avian influenza H5N1, Ebola) that have failed to develop into globe-spanning pandemics have given the international community a sense of security. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is undermining this sense of security because it is proving both highly transmissible (like H1N1) and not too deadly (unlike Ebola). The result is a relatively easily transmitted virus with a case fatality rate currently estimated as well above that of the seasonal influenza. With its high transmissibility and rapid global circulation, COVID-19 is being compared with the deadly Spanish flu outbreak of 1918.1

On 30 January, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern. Since erupting in China, it has claimed thousands of lives there, and has now spread globally, causing infections, death and growing alarm. The WHO's initial focus was on managing droplet and contact transmission, but it has since recognized the role fomites play as well.2 Fomites are important because while populations generally protect themselves from clearly observable droplet transmissions (coughing, sneezing), being invisible, fomite transmission is regularly overlooked both in hospitals and communities.3, 4, 5 Consequently, during the community saturation phase, fomite transmission may play a larger role than droplet transmission as a mechanism in emergent infectious diseases.3, 4, 5, 6

In this paper we argue that by implementing enhanced Traffic Control Bundling (eTCB),6 an extension of the TCB deployed by Taiwan during the 2003 SARS outbreak, countries can interrupt the community-hospital-community transmission cycle, thereby limiting COVID-19's impact.

During SARS 2003, Taiwan implemented a nationwide version of TCB that proved effective at minimizing nosocomial infection of healthcare workers (HCWs), patients, and visitors to hospitals.3 , 4 Traffic Control Bundling is a version of multi-modal care that Taiwan has successfully implemented in the past.7 , 8 TCB is an integrated infection control strategy that include triage prior to entering hospitals; strict separation among zones of risk, and; strict requirements and protocols for personal protective equipment (PPE) use coupled with checkpoint hand disinfection.3

TCB protocols include initial “triage outside of hospitals” - patients found to be infected with SARS-CoV during triage at outdoor fever screening stations are sent directly through a guarded control route to a designated contamination zone; “zones of risk” - clearly distinguished contamination, transition and clean zones. HCWs moving from contamination to clean zones must undertake decontamination and degowning in the transition zone, and hand disinfection at every checkpoint between the zones.

During the Taiwan SARS outbreak, this strategy achieved 100% hand hygiene compliance among HCWs. When coupled with strict PPE use and standard infection control procedures, hospital fomite, contact and droplet transmissions were efficiently controlled. As a result, community SARS infection rates declined as well. Success was evidenced by no new diagnosed cases over two one-week incubation periods following TCB implementation.3 , 4

TCB is particularly effective as regards to the role of fomites. As noted, fomite transmission played a central role in SARS 2003. However, fomites have also proven important during other outbreaks. As with SARS, during MERS 2015 there were numerous examples of HCWs contracting the virus even when fully gowned and often despite having had no direct contact with carriers.6 For example, during the Korean MERS outbreak, one super-spreader infected 82 people in a medical center. Initial analyses pointed to transmission by the index case via droplets and contact with exposed people in the same care zone. However, later analysis found that those without contact history with the index case were likely infected by fomites on bed curtains and/or public restroom fixtures touched by the index case who had been suffering from walking pneumonia and diarrhea.9 Similar findings were identified regarding interactions of fomite-related nosocomial and community transmissions during H1N1 2009 and Ebola 2014.4, 5, 6

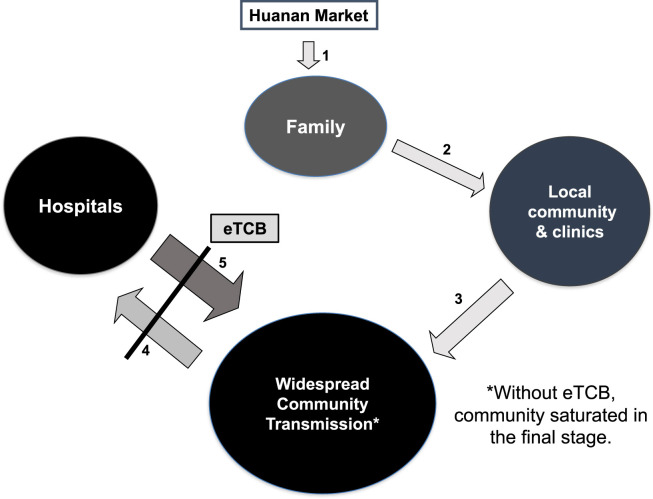

In the COVID-19 case, after a long incubation period, family clusters related to Huanan market developed (Fig. 1 , arrow 1). Early in the outbreak, much as with SARS, transmission via droplets and fomites began cycling between the local community and clinics and hospitals via waiting rooms crowded by both ill and healthy people (Fig. 1, arrow 2). In this case, nosocomial spread began among both HCWs and visitors to the hospitals, who when returning home, re-infected their communities (Fig. 1, arrow 3). This process extended the transmission cycle in a positive feedback loop, amplifying the outbreak (Fig. 1, arrows 4 &5) and cascading to the point of community saturation (Fig. 1).4

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism of community-hospital-community chain of amplification in COVID-19.

In short, following a dynamic similar to earlier coronavirus outbreaks, COVID-19 spread from the Wuhan epicenter to nearby communities and outward within China and internationally. However, COVID-19 has some unique characteristics. These include asymptomatic infection; a hyper-affinity to ACE2 receptors resulting in high transmissibility; false negatives, and; an incubation period of up to 22 days.10 , 11 These characteristics necessitate enhancement to the TCB protocols to ensure effective transmission control.6

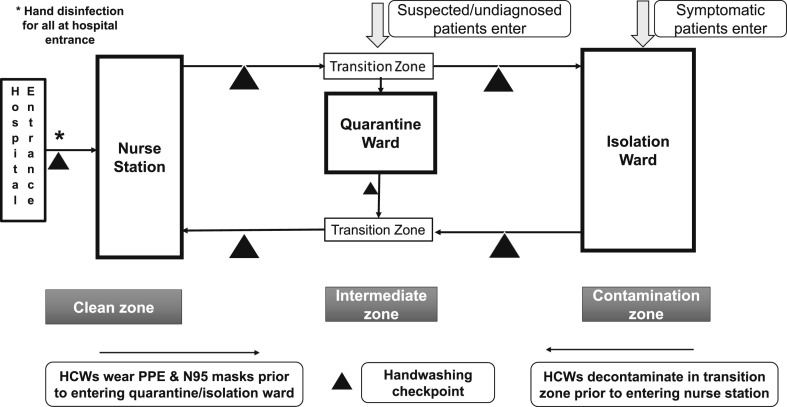

Enhanced TCB (eTCB) includes two enhancements to traditional TCB. First, where TCB has a contamination zone (Isolation ward) and a transition zone, eTCB expands the transition zone to incorporate a quarantine ward as well. The quarantine ward houses patients with atypical manifestations and patients awaiting final diagnosis. These patients are transferred to the quarantine ward directly from outdoor triage and are held there for the full incubation period.6 (Fig. 2 ).

Figure 2.

Enhanced traffic control bundling.

As with traditional TCB, the zones are separated by a transition zone with checkpoints for hand disinfection. HCWs moving from the clean zone to quarantine ward must first dress in PPE. When transitioning from the quarantine to the isolation ward, HCWs must engage in comprehensive checkpoint disinfection, a process repeated as they move from the isolation ward to the clean zone (again, via a transition zone).

Second, to address community to hospital infection threats, checkpoint hand disinfection and face masks are required of all visitors entering the hospital. This is supplemented with heightened environmental cleaning and disinfection.

COVID-19 droplet and fomite transmission has been observed both inside and outside of hospitals. By containing nosocomial transmissions, eTCB contributes to breaking the cycle of community-hospital-community infection. Recently, Taiwan's COVID-19 response was praised in public health circles.12 Taiwan's success can be at least partially attributed to its success in breaking the community-hospital-community transmission cycle by implementing TCB with the enhancements identified here. We therefore strongly recommend implementing eTCB as an important tool for containing COVID-19.

Author contributions

Initiated this study and structure of this paper: MY Yen, J Schwartz.

Conceived and designed this study: MY Yen, J Schwartz, SY Chen.

Wrote the paper: MY Yen, J Schwartz, CC King.

Setting up the Traffic Control Bundle: MY Yen, SY Chen.

Literature search: MY Yen, CC King, GY Yang, PR Hsueh.

Data collection: MY Yen, GY Yang.

Analyzed the data: MY Yen, CC King, GC Yang.

Data interpretation: MY Yen, CC King, GC Yang.

Figure: MY Yen, J Schwartz, SY Chen, PR Hsueh.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

The funding of the retrospective study in confirming the efficacy of traffic control bundling (reference 3. Yen MY, et al. Taiwan's traffic control bundle and the elimination of nosocomial severe acute respiratory syndrome among health care workers. J Hosp Infect 2011;77:332–7) was financially supported by Taiwan CDC grant (DOH 92-DC-SA01) in 2003.

References

- 1.Morens D.M., Daszak P., Taubenberger J.K. Escaping Pandora's Box — another novel coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2020 February 26 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong S.W.X., Tan Y.K., Chia P.Y., Lee T.H., Ng O.T., Wong M.S.Y. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 Mar 4 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yen M.Y., Lin Y.E., Lee C.H., Ho M.S., Huang F.Y., Chang S.C. Taiwan's traffic control bundle and the elimination of nosocomial severe acute respiratory syndrome among health care workers. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen M.Y., Chiu A.W.-H., Schwartz J., King C.C., Lin Y.E., Chang S.C. From SARS in 2003 to H1N1 in 2009: lessons learned from Taiwan in preparation for the next pandemic. J Hosp Infect. 2014;87:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yen M.Y., Schwartz J., Chiu A.W.H., Armstrong D., Hsueh P.R. Traffic control bundling is essential for protecting healthcare workers and controlling the ebola epidemic 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:823–825. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz J., King C.C., Yen M.Y. Protecting health care workers during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak-lessons from Taiwan's SARS response. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 March 12 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kao C.C., Chiang H.T., Chen C.Y., Hung C.T., Chen Y.C., Su L.H. National bundle care program implementation to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care units in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52:592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai C.C., Cia C.T., Chiang H.T., Kung Y.C., Shi Z.Y., Chuang Y.C. Implementation of a national bundle care program to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in intensive care units in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2018;51:666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho S.Y., Kang J.M., Ha Y.E., Park G.E., Lee J.Y., Ko J.H. MERS-CoV outbreak following a single patient exposure in an emergency room in South Korea: an epidemiological outbreak study. Lancet. 2016;388:994–1001. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30623-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai C.C., Liu Y.H., Wang C.Y., Wang Y.H., Hsueh S.C., Yen M.Y. Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV-2): facts and myths. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 March 4 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020 Feb 19 doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. pii: eabb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C.J., Ng C.Y., Brook R.H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 March 3 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]