Abstract

Objective

To specifically report on ataxic-hypotonic cerebral palsy (CP) using registry data and to directly compare its features with other CP subtypes.

Methods

Data on prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal characteristics and gross motor function (Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS]) and comorbidities in 35 children with ataxic-hypotonic CP were extracted from the Canadian Cerebral Palsy Registry and compared with 1,804 patients with other subtypes of CP.

Results

Perinatal adversity was detected significantly more frequently in other subtypes of CP (odds ratio [OR] 4.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–11.7). The gestational age at birth was higher in ataxic-hypotonic CP (median 39.0 weeks vs 37.0 weeks, p = 0.027). Children with ataxic-hypotonic CP displayed more intrauterine growth restriction (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.0–6.8) and congenital malformation (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2–4.8). MRI was more likely to be either normal (OR 3.8, 95% CI 1.4–10.5) or to show a cerebral malformation (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.9) in ataxic-hypotonic CP. There was no significant difference in terms of GMFCS or the presence of comorbidities, except for more frequent communication impairment in ataxic-hypotonic CP (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.6).

Conclusions

Our results suggest a predominantly genetic or prenatal etiology for ataxic-hypotonic CP and imply that a diagnosis of ataxic-hypotonic CP does not impart a worse prognosis with respect to comorbidities or functional impairment. This study contributes toward a better understanding of ataxic-hypotonic CP as a distinct nosologic entity within the spectrum of CP with its own pathogenesis, risk factors, clinical profile, and prognosis compared with other CP subtypes.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is an umbrella term for a heterogeneous group of disorders that by definition all necessarily feature an early-onset impairment of movement and posture secondary to a nonprogressive pathology of the CNS.1,2 Although the diagnosis of CP remains a clinical one, controversy regarding specific subtype criteria persists.3 Characterization of an individual's CP is typically based on either the predominant type and distribution of motor symptoms or on the degree of functional impairment noted in a particular domain.4

Ataxic and hypotonic forms of CP are the rarest subtypes of CP, with a prevalence consistently estimated at less than 5% of all CP cases,4,5 and robust data are generally lacking. The objective of this study was to develop a profile of children with ataxic and/or hypotonic CP in Canada using the Canadian Cerebral Palsy Registry (CCPR). We compared the prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal characteristics of children with ataxic-hypotonic CP with those of children with other CP subtypes. We hypothesized that patients with ataxic-hypotonic CP would have less prenatal and perinatal risk factors, higher odds of having abnormal imaging results, worse functional disability, and more comorbidities compared with all other CP subtypes. The findings from this study will enhance our understanding of the clinical profile and distinguishing features of ataxic-hypotonic CP to hopefully provide more accurate prognostication and better individualized care to affected children and families.

Methods

Data were obtained from the CCPR, a registry that draws from approximately half the Canadian population and includes patients with CP born since 1999.4 Case ascertainment and data collection methods of the registry have been well described in multiple previous publications.6–13 To be enrolled in the CCPR, children must be aged 2 years or older and meet the international consensus criteria for CP.14

In accordance with the current guidelines, patients in the registry are diagnosed purely clinically. The Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe classification tree15 is recommended for determining subtype. The registry does not collect standardized data regarding a genetic workup.

Ataxic and hypotonic CP were grouped together for the purpose of this study in the context of their aforementioned low prevalence and known overlap. Studies at present are not consistent in terms of how they classify CP subtypes5 and which subtypes they include. In fact, several classifications of CP subtypes, such as the one proposed by the Executive Committee for the Definition of Cerebral Palsy,16 eschew hypotonic CP entirely. However, there is precedence in the literature for conflating ataxia and hypotonia in CP clinically and at the registry level.15,17,18

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Ethical approval for the CCPR was obtained from the host institution (The Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre: RI-MUHC) and locally from each participating center; informed consent was obtained for each participant.

Variables of interest

Data extracted from the CCPR included prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal risk factors for CP, functional outcomes, and CP phenotypic data. Prenatal variables of interest were mother's age at the time of birth (years) and the following binary (yes/no) variables: hypertension during pregnancy, gestational diabetes, alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug and prescription drug use during pregnancy, severe illness during pregnancy, and perinatal adversity. Perinatal adversity was defined as meeting 2 or more of the following criteria: Apgar score of 5 or less at 5 minutes, cord pH <7.0, moderate to severe neonatal encephalopathy, or emergency cesarean section.

Neonatal characteristics of interest were gestational age (weeks), birthweight (kilograms), congenital microcephaly, congenital malformation, and MRI findings (normal, deep gray matter injury, bilateral white matter injury, watershed injury, near-total brain injury, focal insult, malformation, and other). Congenital microcephaly was defined as having head circumference below the 3rd percentile for sex and gestational age.19 Congenital malformation was determined by the presence of one or more of the following binary (yes/no) variables: congenital malformation, congenital microcephaly, a metabolic condition, a syndrome, and malformation identified on MRI.

Gross motor function was assessed using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) and categorized dichotomously as I–III (less severe motor impairment, ambulatory with or without assistance) and IV–V (more severe motor impairment, nonambulatory). Comorbidities captured within the CCPR were visual, sensorineural auditory, communication, feeding, and cognitive impairment, as well as convulsions (all binary yes/no variables).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were derived to obtain a profile of the sample of children with ataxic-hypotonic CP. Chi-squared tests were performed to compare categorical characteristics of children with ataxic-hypotonic CP with the rest of the sample. The Fisher exact test was used when cell counts were below the minimum expected value of 5. Student t tests were performed to compare normally distributed continuous variables between children with ataxic-hypotonic CP and the rest of the sample. Nonparametric tests were performed where applicable. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated where appropriate.

Data availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

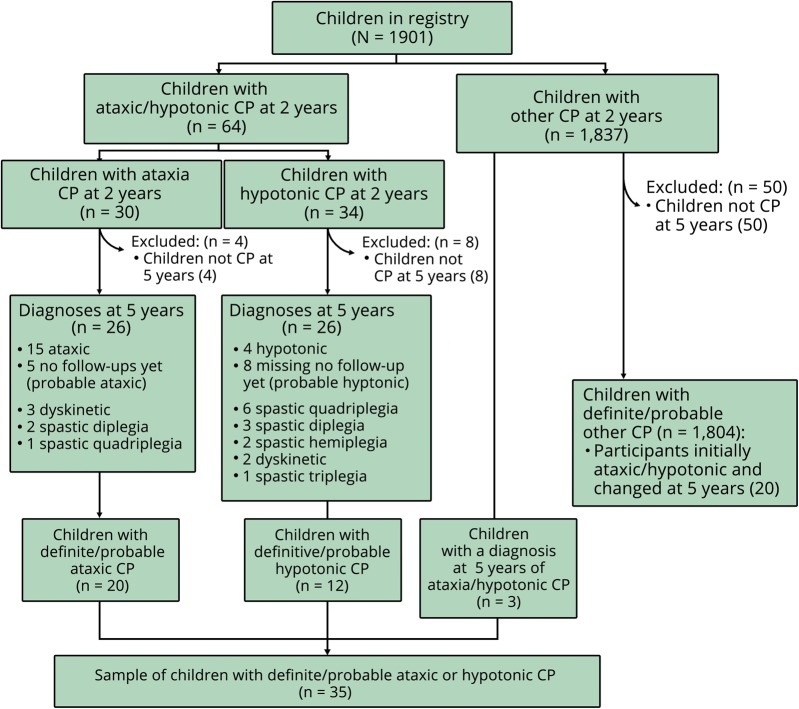

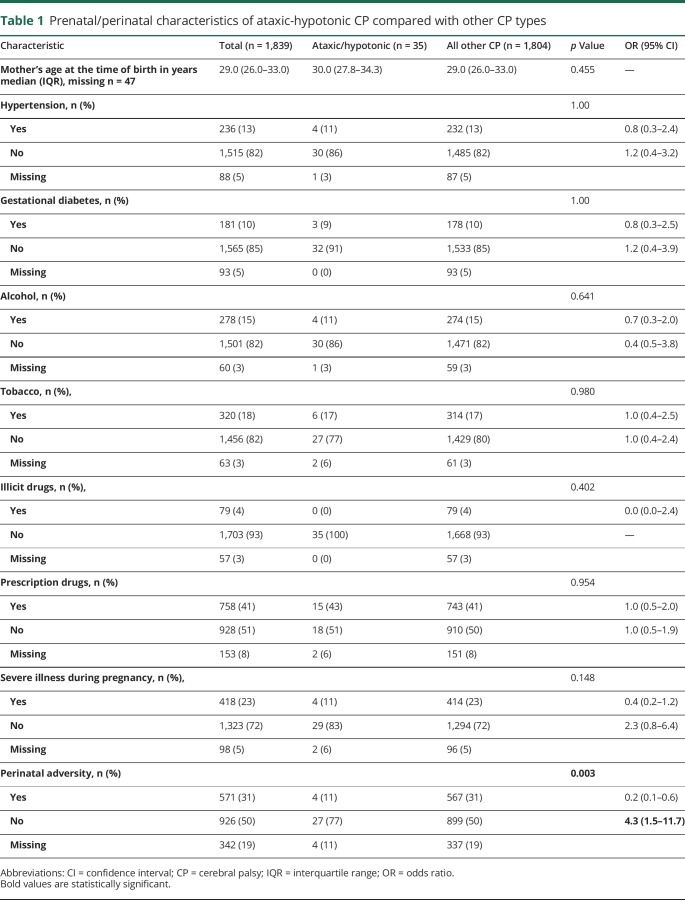

A total of 1,901 patients with a CP diagnosis at age 2 years were identified from the CCPR, of which 62 (3%) had not retained their CP diagnosis at 5 years, resulting in a sample of 1,839 children with definite or probable CP. A total of 35 children (2%) represented cases of definite or probable ataxic-hypotonic CP at 5 years (figure). Compared with the 1,804 patients with other forms of CP, there was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of multiple prenatal factors. However, children with a CP subtype other than ataxic-hypotonic CP had greater odds of perinatal adversity (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.5–11.7) compared with children with ataxic-hypotonic CP. These results are shown in table 1.

Figure. Participant flow diagram.

Table 1.

Prenatal/perinatal characteristics of ataxic-hypotonic CP compared with other CP types

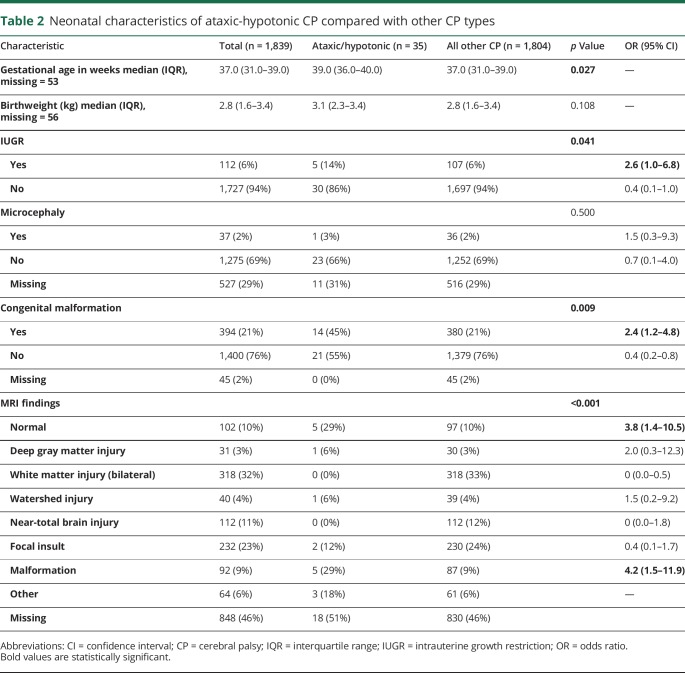

Neonatal characteristics are shown in table 2. The gestational age was higher in ataxic-hypotonic patients: median 39.0 weeks (interquartile range [IQR] 36.0–40.0), compared with a median of 37.0 weeks (IQR 31.0–39.0) for other types of CP (p = 0.027). There was no significant difference in birth weight or microcephaly at birth between the 2 groups. Children with ataxic-hypotonic CP were more likely to have intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.0–6.8) and congenital malformation compared with children with other CP subtypes (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2–4.8). Forty-four percent of congenital malformations were brain malformations, with a larger proportion present in children with ataxic-hypotonic CP (79%) compared with other CP (43%) subtypes (p = 0.012).

Table 2.

Neonatal characteristics of ataxic-hypotonic CP compared with other CP types

Children with ataxic-hypotonic CP had higher odds of a normal MRI (OR 3.8, 95% CI 1.4–10.5) or a malformation on MRI (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.9) compared with other CP subtypes. Table e-1 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A125) outlines the types of malformations identified on MRI. Of interest, the most common MRI finding across all other CP types was bilateral white matter injury in 33%, which was detected in none of the ataxic-hypotonic CP MRI studies.

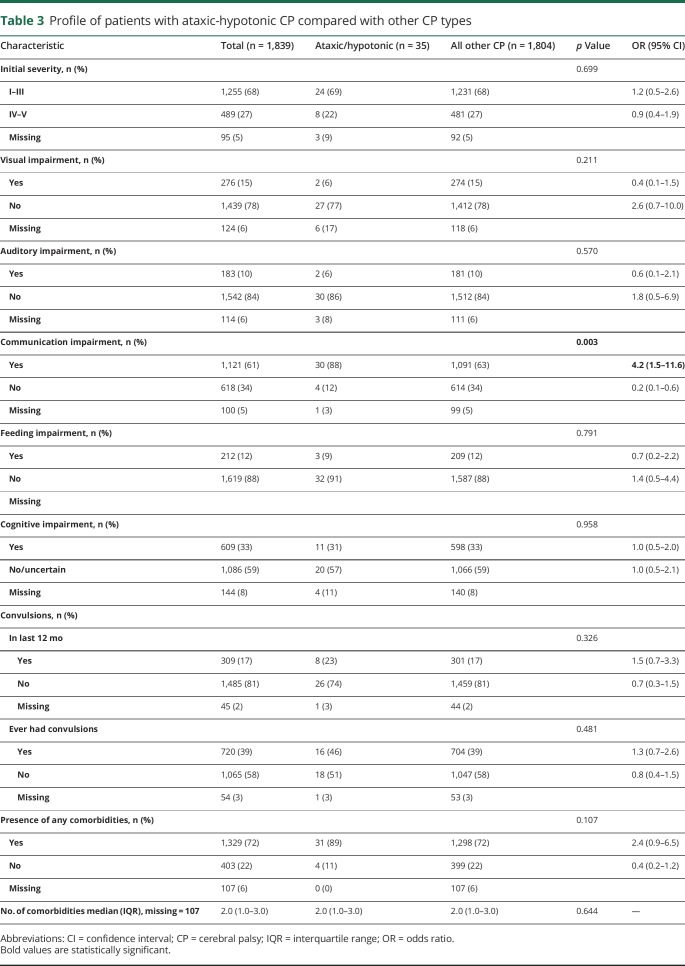

The clinical profile of patients with ataxic-hypotonic CP is outlined in table 3. There was no significant difference between the ataxic-hypotonic CP cases and the other CP types in terms of GMFCS or the presence of comorbidities, including visual impairment, auditory impairment, convulsions, feeding, or cognitive impairment. However, there was a difference with respect to communication: children with ataxic-hypotonic CP had higher odds of having a communication impairment (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.6).

Table 3.

Profile of patients with ataxic-hypotonic CP compared with other CP types

Discussion

Ataxic-hypotonic CP represents a distinct subset of the CP population wherein ataxia and/or hypotonia constitutes the key motor manifestations. It is currently diagnosed clinically and is poorly understood in part due to its rarity and inconsistencies in definition and case ascertainment across studies. Although previous articles have used registry data to describe ataxic CP, preexisting research specifically focusing on describing ataxic-hypotonic CP at the population level and directly comparing it with other forms of CP is virtually nonexistent.

Our data showed that children with ataxic-hypotonic CP experienced significantly less perinatal adversity and were more likely to be born at term than children with other types of CP, suggesting a different causal pathway for ataxic-hypotonic CP. IUGR and congenital malformation were also observed more frequently in ataxic-hypotonic CP. Furthermore, the MRI had higher odds of being normal or showing a cerebral malformation in ataxic-hypotonic CP.

Of note, a large percentage of patients were missing an MRI. We believe that this is a direct result of MRI not having been widely available in Canada for much of the initial period covered by the registry. In support of this, we found a comparable profile in terms of prematurity, perinatal adversity, comorbidities, and GMFCS between the children with ataxic-hypotonic CP who had received an MRI and those without an MRI. In addition, there was no significant difference between the proportions of missing MRI in the ataxic-hypotonic CP group and the other types of CP (p = 0.524).

Overall, our findings are consistent with previously published articles,20–23 which have suggested that up to 100% of cases of ataxic CP may be attributed to an underlying genetic cause,20 and have identified pathogenic de novo mutations in specific genes (e.g., KCNC3, ITPR1, and SPTBN2).21 The general picture of malformation in the context of less perinatal risk factors indeed points toward a predominantly genetic or prenatal etiology or pathway for ataxic-hypotonic CP.

In addition, we compared patient profiles, a subject that remains controversial in the literature to date. An earlier study using the Cerebral Palsy Registry in the province of Quebec found that patients with ataxic or hypotonic CP experienced the most frequent comorbidities (i.e., seizures, severe auditory impairment, and cortical blindness) compared with other subtypes, although this did not reach statistical significance with only 9 children in the ataxic-hypotonic CP subgroup.17 A 2016 profile of comorbidities in 3,466 patients from the Australian Cerebral Palsy Registry found overall more frequent comorbidities in nonspastic CP subtypes (except for epilepsy), but notably, this study considered ataxic and hypotonic CP separately.24 On the other hand, a 2006 population-based study from Sweden suggested that compared with other CP subtypes, children with ataxic CP were more likely to have a lower GMFCS and less comorbidities. However, this study included a total of 14 children with ataxic CP, did not address hypotonic CP, and only examined learning disability, epilepsy, and visual impairment in terms of comorbidities.25

Our study did not detect any significant differences in GMFCS or comorbidities between the 2 groups, except for more communication difficulties in ataxic-hypotonic CP. This may be due to the now recognized role played by the cerebellum in language production and processing.26 Of interest, in contrast to our results, a 2006 study using data from 8 European centers did not find an elevated rate of communication difficulties in ataxic CP relative to other CP subtypes.23 Our findings do imply that other than the aforementioned communication difficulties, which certainly merit further investigation, a diagnosis of ataxic-hypotonic CP does not impart a worse prognosis with respect to comorbidities or gross motor functional impairment within the spectrum of CP encountered.

The ability to draw conclusions from our data is largely limited by the still small absolute numbers of identified patients with ataxic-hypotonic CP despite a robust and wide case ascertainment approach enabled by a CP registry. It is also likely that these rare subtypes remain underrecognized. For example, the diagnosis of CP may often be missed in an ataxic child with normal imaging. This situation is further complicated by the known variability both between and within clinicians in distinguishing ataxia from dystonia and spasticity.27 In addition, the lack of a consensus between studies in terms of how to classify CP subtypes acts as an inherent limitation with respect to comparing data obtained (e.g., considering ataxia and hypotonia as representing 2 separate subtypes24 vs including ataxic but not hypotonic CP28 vs grouping ataxic-hypotonic subtypes together15,17,18). This information, in concert with our results that suggest a genetic etiology for ataxic-hypotonic CP, supports a role for pursuing genetic testing in the diagnosis of atypical forms of CP. Ultimately, an important goal for the future will be to establish a clear unifying definition of ataxic-hypotonic CP to be used at different institutions, thereby permitting collaboration across national registries. This will enable more effective data collection, which is essential given the rarity of ataxic-hypotonic CP.

The potential for this article to affect clinical practice lies in its contributing to a better understanding of ataxic-hypotonic CP as a distinct nosologic entity, with the goal of working toward more accurate diagnosis and prognostication. Many conditions are known to masquerade as ataxic-hypotonic CP (“CP mimics”) including coenzyme Q10 deficiency, congenital disorders of glycosylation, MECP2 duplication syndrome, Angelman syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia, and others.29 Improved understanding of ataxic-hypotonic CP may thus also be valuable to help clinicians exclude potential mimickers. Distinguishing between genetic etiologies of CP vs other causes that would exclude a diagnosis of CP will also need to be further explored in future studies.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This study was funded by Kids Brain Health Network.

Disclosure

J.P. Levy reports no disclosures. M. Oskoui has received funding from Kids Brain Health Network, the Fonds de Recherche Sante du Québec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the McGill University Health Centre Research Institute, the SickKids Foundation, and the Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation; serves as site PI for clinical trials in SMA funded by Ionis, Biogen, Roche, and Cytokinetics and has been reimbursed for travel related to these trials; and has received funding for travel from the American Academy of Neurology to attend their specific meetings. P. Ng reports no disclosures. J. Andersen has received honorarium and financial support for travel from Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals Canada Inc. and Allergan Canada for consultation services and educational activities. D. Buckley reports no disclosures. D. Fehlings has received funding from Kids Brain Health Network, the Ontario Brain Institute, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Centre for Leadership at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. A. Kirton has received research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and fees for expert medicolegal work. L. Koclas, N. Pigeon, E. van Rensburg, and E. Wood report no disclosures. M. Shevell has received funding by NeuroDevNet (now Kids Brain Health Network) and receives support from the Harvey Guyda Chair Fund of the Montreal Children's Hospital Foundation. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ Ataxic-hypotonic CP is distinct from other forms of CP.

→ In the CCPR, children with ataxic-hypotonic CP were found to have significantly less perinatal adversity and were more likely to be born at term than children with different types of CP. Children with ataxic-hypotonic CP also more commonly had IUGR or congenital malformation and had higher odds of either a normal MRI or a cerebral malformation compared with other types of CP.

→ No significant difference was found between the groups in terms of GMFCS or comorbidities, except for more communication difficulties in ataxic-hypotonic CP.

→ Our results point toward a predominantly genetic or prenatal etiology for ataxic-hypotonic CP and imply that a diagnosis of ataxic-hypotonic CP does not impart a worse prognosis with respect to comorbidities or functional impairment.

→ Moving forward, it will be essential to establish a clear unifying definition of ataxic-hypotonic CP to enable more effective research on this rare and likely underrecognized disorder.

References

- 1.Graham HK, Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, et al. Cerebral palsy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wimalasundera N, Stevenson VL. Cerebral palsy. Pract Neurol 2016;16:184–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smithers-Sheedy H, Badawi N, Blair E, et al. What constitutes cerebral palsy in the twenty-first century? Dev Med Child Neurol 2014;56:323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shevell M, Dagenais L, Oskoui M. The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: new perspectives from a Canadian registry. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2013;20:60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid SM, Carlin JB, Reddihough DS. Distribution of motor types in cerebral palsy: how do registry data compare? Dev Med Child Neurol 2011;53:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider RE, Ng P, Zhang X, et al. The association between maternal age and cerebral palsy risk factors. Pediatr Neurol 2018;82:25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolbocean C, Wintermark P, Shevell MI, Oskoui M. Perinatal regionalization and implications for long-term Health outcomes in cerebral palsy. Can J Neurol Sci 2016;43:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank R, Garfinkle J, Oskoui M, Shevell MI. Clinical profile of children with cerebral palsy born term compared with late- and post-term: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG 2017;124:1738–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freire G, Shevell M, Oskoui M. Cerebral palsy: phenotypes and risk factors in term singletons born small for gestational age. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2015;19:218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garfinkle J, Wintermark P, Shevell MI, Oskoui M. Cerebral palsy after neonatal encephalopathy: do neonates with suspected asphyxia have worse outcomes? Dev Med Child Neurol 2016;58:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garfinkle J, Wintermark P, Shevell MI, Oskoui M. Children born at 32 to 35 weeks with birth asphyxia and later cerebral palsy are different from those born after 35 weeks. J Perinatol 2017;37:963–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garfinkle J, Wintermark P, Shevell MI, Platt RW, Oskoui M. Cerebral palsy after neonatal encephalopathy: how much is preventable? J Pediatr 2015;167:58–63.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smilga AS, Garfinkle J, Ng P, et al. Neonatal infection in children with cerebral palsy: a registry-based cohort study. Pediatr Neurol 2018;80:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007;109:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE). Dev Med Child Neurol 2000;42:816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bax M, Goldstein M, Rosenbaum P, et al. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy, April 2005. Dev Med Child Neurol 2005;47:571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shevell MI, Dagenais L, Hall N. Comorbidities in cerebral palsy and their relationship to neurologic subtype and GMFCS level. Neurology 2009;72:2090–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minear WL. A classification of cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 1956;18:841–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris SR. Measuring head circumference: update on infant microcephaly. Can Fam Physician 2015;61:680–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costeff H. Estimated frequency of genetic and nongenetic causes of congenital idiopathic cerebral palsy in west Sweden. Ann Hum Genet 2004;68:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parolin Schnekenberg R, Perkins EM, Miller JW, et al. De novo point mutations in patients diagnosed with ataxic cerebral palsy. Brain 2015;138:1817–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rankin J, Cans C, Garne E, et al. Congenital anomalies in children with cerebral palsy: a population-based record linkage study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010;52:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bax M, Tydeman C, Flodmark O. Clinical and MRI correlates of cerebral palsy: the European cerebral palsy study. JAMA 2006;296:1602–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delacy MJ, Reid SM. Profile of associated impairments at age 5 years in Australia by cerebral palsy subtype and Gross Motor Function Classification System level for birth years 1996 to 2005. Dev Med Child Neurol 2016;58(suppl 2):50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Himmelmann K, Beckung E, Hagberg G, Uvebrant P. Gross and fine motor function and accompanying impairments in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006;48:417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marien P, Ackermann H, Adamaszek M, et al. Consensus paper: language and the cerebellum: an ongoing enigma. Cerebellum 2014;13:386–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggink H, Kremer D, Brouwer OF, et al. Spasticity, dyskinesia and ataxia in cerebral palsy: are we sure we can differentiate them? Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2017;21:703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yim SY, Yang CY, Park JH, et al. Korean database of cerebral palsy: a report on characteristics of cerebral palsy in South Korea. Ann Rehab Med 2017;41:638–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee RW, Poretti A, Cohen JS, et al. A diagnostic approach for cerebral palsy in the Genomic Era. Neuromolecular Med 2014;16:821–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.