Abstract

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a respiratory disease from a novel coronavirus that was first detected in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China, is now a public health emergency and pandemic. Singapore, as a major international transportation hub in Asia, has been one of the worst hit countries by the disease. With the advent of local transmission, the authors share their preparation and response planning for the operating room of the National Heart Centre Singapore, the largest cardiothoracic tertiary center in Singapore. Protection of staff and patients, environmental concerns, and other logistic and equipment issues are considered.

Key Words: COVID-19, operating room, outbreak, response, pandemic

A CLUSTER of novel acute respiratory diseases presenting with a broad clinical spectrum, now known to be caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first detected in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, and was reported to the World Health Organization's (WHO's) office in China on December 31, 2019.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Current evidence suggests a zoonotic source of human transmission, likely arising from illegal wildlife trade at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.3 , 5 On February 11, 2020, WHO renamed the disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).8 Since then, COVID-19 has spread rapidly from Wuhan to many other countries worldwide, given the ease of both viral transmission and global air travel, and prompted the lockdown of several cities in the Hubei province by Chinese authorities.9 Despite the aggressive containment measures by China, there are now more than 1.2 million cases worldwide with a death toll exceeding 70,000.10 In light of the worsening global situation, WHO declared the COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020.11

Singapore, being the main transportation hub and a popular tourist destination for mainland Chinese tourists in Southeast Asia,12 had the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases outside of China in the early stages of the outbreak.13 The first imported case from China was reported on January 23, 2020,14 and the first locally transmitted case on February 4, 2020.15 Within 2 weeks after the first case hit its shores, Singapore raised its Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level to orange, prompting additional precautionary measures nationwide.16 The DORSCON framework was drafted after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 and serves as a guide for the country's response to pandemics.17 It was last declared orange during the H1N1 outbreak in 2009.18

Unlike in the SARS outbreak for which Tan Tock Seng Hospital was designated to manage all SARS-infected patients,19 currently all government and privately owned hospitals in Singapore have individual infectious disease units with isolation ward capabilities to manage highly infectious patients.20 , 21 The National Heart Centre Singapore (NHCS) opened in 2014 and is the largest adult cardiothoracic tertiary center in Singapore.22 This article aims to outline the guidelines and modifications for operating room (OR) preparation for the management of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients presenting for emergency cardiac surgery in NHCS.

NHCS

The NHCS is located on the Outram campus of the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) and is connected to the main SGH building via a link bridge. It houses 6 operating rooms, 4 of which are dedicated to cardiothoracic surgeries. Since 2014, all elective cardiac surgeries have been performed within the NHCS operating complex, and patients are transported across the link bridge to the cardiothoracic intensive care unit in SGH postoperatively if intensive care is required. However, after-office hours emergency surgeries are performed within the major operating complex in SGH.

When news of the COVID-19 outbreak surfaced in January 2020, hospitals in Singapore were placed on high alert immediately for suspected and confirmed cases. Elective surgeries were reduced to allow for potential surges in admissions requiring hospital beds. General wards were cleared and designated as isolation wards. All nonurgent training, meetings, conferences, and leave were cancelled. Visitor numbers were reduced, and all visitors were required to be screened before entry.

Health Care Workers

Personal Protection

The infectious disease and occupational health departments stepped up infection control measures and conducted N95 mask fitting sessions across all departments. Powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) training was provided for health care workers (HCW) working in potential high-risk areas. Staff surveillance and temperature recording via the Ministry of Health platform were required twice a day. Frequent OR simulations were conducted to allow members of the surgical team to familiarize themselves with the use of PAPR and infection control workflow.

Staff Deployment

In line with the heightened alert, health care staff movement among the various health care institutions in Singapore was restricted. Measures also were taken to prevent OR cross-contamination among HCW. This included dividing staff members into teams such that if one team was exposed accidentally to an undiagnosed COVID-19 patient, team members would be taken out of the elective roster until they were cleared. In addition, the Department of Perfusion allocated dedicated personnel to manage both the intensive care unit (ICU) and OR separately. Besides providing services in NHCS, perfusionists also support the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation services in both SGH and the National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID). An extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support team, made up of 2 perfusionists, 1 cardiothoracic surgeon, and an intensivist, is rostered to the NCID, whereas a second team provides similar support for COVID-19 patients admitted to SGH.

OR Modifications

Once the DORSCON orange alert was activated, elective surgeries within NHCS were reduced immediately to 3 elective surgical lists from 4. All surgeries of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients were assigned to be performed in a dedicated smaller operating complex located away from the main operating complex. The COVID-19 designated operating complex consists of 3 operating rooms located in the main SGH building but separated from the main operating complex to avoid patient and OR cross-contamination. Each OR has its own separate humidity, laminar airflow, and air conditioning systems.

Droplet Precautions

The mode of transmission for SARS-CoV-2 appears to be droplet in nature and not airborne.23 Hence, adherence to droplet precautions and proper environmental, hygiene, and sound infection control practices are indicated.23 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that airborne infection isolation rooms be reserved only for patients undergoing aerosol-generating procedures.23 These rooms are negative-pressure areas and are recommended for airborne infections because they prevent microorganisms from escaping into hallways and corridors.24 After the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, the United Christian Hospital successfully converted 1 of their positive-pressure ORs into a negative-pressure OR for surgical patients with airborne infections.25 Likewise in Singapore during the SARS outbreak, negative-pressure rooms were created by attaching exhaust fans with high-efficiency particulate air filters to windows.

Currently, all COVID-19 confirmed patients in Singapore are admitted to negative-pressure isolation rooms in isolation wards. Ideally, all COVID-19 suspected or confirmed patients should undergo surgery in a negative-pressure OR to reduce contamination of adjoining corridors or rooms. However, both the NHCS and SGH lack such a facility. To address this issue, OR doors must remain closed for at least 10 minutes after intubation or extubation for the high-efficiency particulate air filters to remove 99% of the particulate air matter because the OR air change rate is approximately 25 times per hour.26

Because SARS-CoV-2 is spread by droplet transmission, it is important that coughing during intubation and extubation be reduced to a minimum to decrease contamination of nearby surfaces; the at-risk area is within 2 meters.27 There should be minimal movement in and out of the OR during surgery. If necessary, the smallest door is used for entry or exit.

Equipment

The anesthetic work environment and its surfaces are at high risk for harboring droplets that can serve as virus reservoirs if proper decontamination processes are not taken. As such, the use of disposable equipment when possible is favored. The main anesthetic drug trolley is kept in the induction room outside the OR, and anesthesiologists are encouraged to bring the necessary drugs required in a sterile disposable tray into the OR before patient arrival. To circumvent problems associated with working in an unfamiliar environment, prepacked intravenous and invasive line insertion sets were created. Ice packs used for surface cooling during deep hypothermic circulatory arrest also were changed to disposable ones. If a difficult airway is anticipated, the GlideScope AVL video laryngoscope system (Verathon Medical Inc, Bothell, WA) with its disposable blade is preferred over the C-MAC video laryngoscope (Karl Storz, Tutlingen, Germany), for which, unfortunately, disposable blades were not purchased. The GlideScope also has a larger screen size compared with other brands of video laryngoscopes. This is of importance when vision and depth perception may be impaired because of eye goggles or PAPR.

Because the COVID-19–designated operating complex is a distance away from both the operating complexes in SGH and NHCS, a work plan was drawn up detailing the required surgical, perfusion, and anesthetic equipment and their locations to facilitate procurement during emergencies. Spare equipment was obtained and stored in the COVID-19–designated operating complex as much as possible to minimize delays and suboptimal use of manpower.

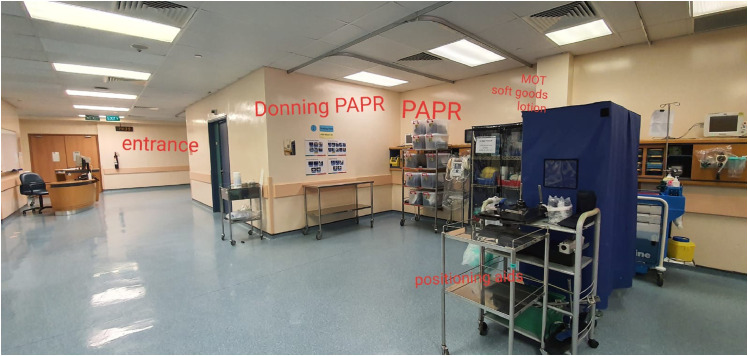

Simulation

A team of cardiothoracic anesthesiologists, surgeons, perfusionists, and nurses carried out a simulation as per the workflow developed during SARS. In 2003, room 3 within the COVID-19–designated operating complex was the designated the SARS-OR. However, during the simulation, it was found that room 3 could no longer accommodate the required equipment necessary for cardiothoracic surgeries. The alternative suggestion was to use room 1, which is more spacious (Fig 1 ). A second simulation subsequently was conducted.

Fig 1.

OR Simulation in Progress.

All relevant equipment that potentially might be used during cardiac surgery was brought into room 1. This included the cardiopulmonary bypass machine, transesophageal echocardiography machine, intra-aortic balloon pump, cerebral oximetry, Belmont Rapid Infuser (Belmont Medical Technologies, Billerica, MA), autologous cell saver, defibrillator, and a simplified drug trolley. A mock patient on an ICU bed with an intra-aortic balloon pump in-situ was transferred into the OR to ensure that there was adequate room for transfer onto the operating table, along with the surgical scrub nurses setting up and preparing their instrument trolley simultaneously.

All HCW used N95 masks and PAPR and took turns to perform their daily duties on normal patients (Fig 2 ). This allowed staff to identify potential problems, raise awareness, and improve systems workflow. For example, the surgical team experienced difficulty in donning the PAPR over their headlights. Reflections from the face shield also affected their vision and depth perception. Issues with battery life also were brought to attention. It was found that having a mirror in the room helped with checking that protective gear was worn properly. In addition, communication between the anesthetic team wearing PAPR and the “clean” runner stationed outside the OR was found to be hindered at times. Written communication via pen and paper was suggested as an alternative.

Fig 2.

HCWs in PAPR during surgery.

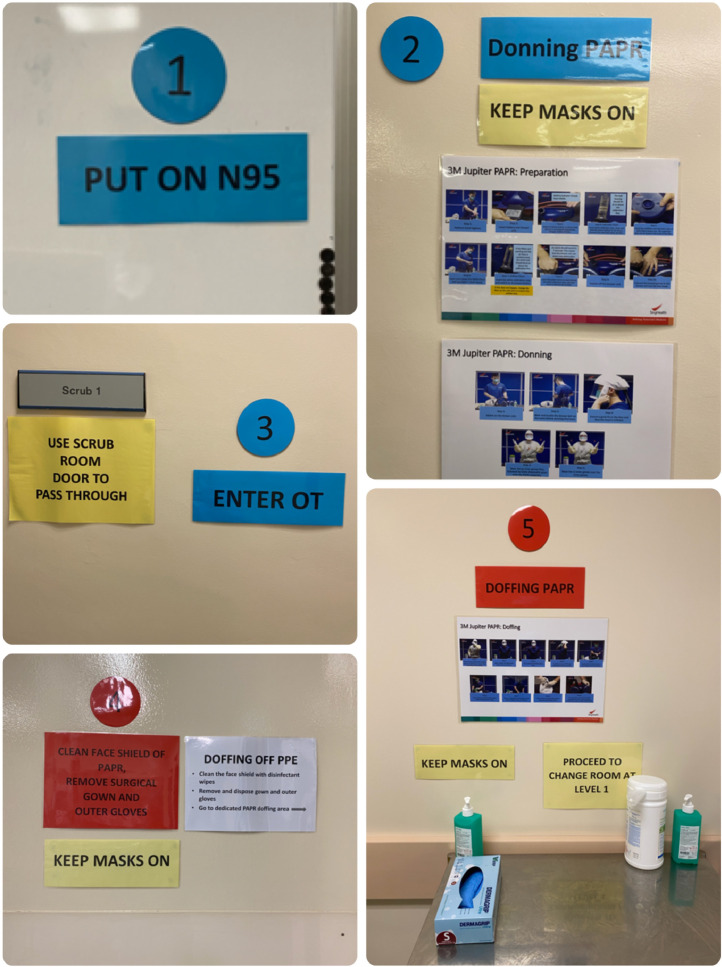

Because of unfamiliarity with the isolation operating complex, planned donning and doffing areas for PAPR were demarcated and signposted (Fig. 3 and 4 ). OR doors also were closed to ensure restricted HCW movement and avoid OR cross-contamination. In addition, senior anesthesiologists were appointed as COVID coordinators to help coordinate manpower and facilitate workflow while allowing the main anesthetic team to concentrate on patient care. Potential routes from the isolation ICU to the OR also were discussed and finalized by the Division of Anesthesiology. Dedicated lifts for the use of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients have been assessed to be wide enough to accommodate a bed, equipment, and accompanying HCW.

Fig 3.

Signages in designated areas for donning and doffing of PPE.

Fig 4.

Signages in designated areas for donning and doffing of PPE.

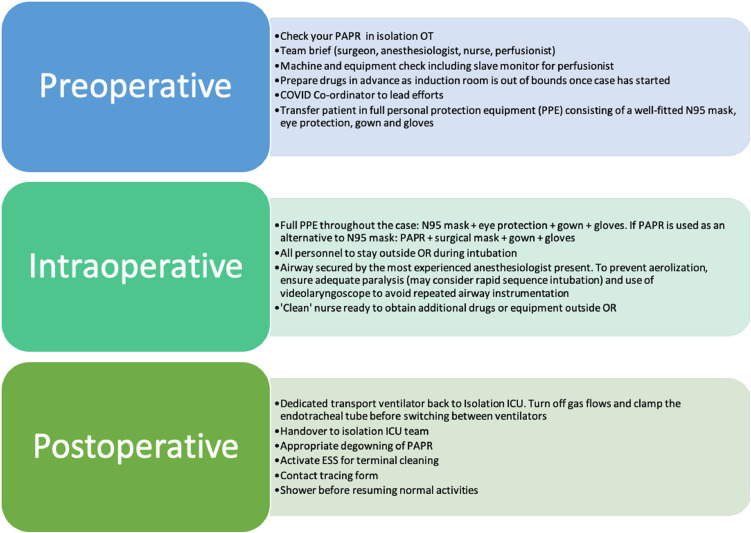

At the end of a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case, all plastic covers over nondisposable equipment are disposed. Surfaces are wiped down, followed by terminal cleaning by environment service staff. This is performed using sodium hypochlorite 1,000 ppm, followed by treatment with hydrogen peroxide vaporization or ultraviolet radiation when hydrogen peroxide vaporization is not feasible. All soiled instruments are placed in double orange biohazard bags, which are cable tied and transferred onto security trucks where staff members from the sterile supplies unit are activated for collection. All medical devices, including PAPR, are wiped down with hospital-approved disinfectant wipes within the OR. Any unused consumables and drugs brought into the OR are discarded. The turnaround time for OR decontamination is about 4 hours. All HCW involved in patient care are documented for contact tracing purposes and must shower and change into clean attire before resuming regular duties. A summary of OR considerations can be found in Fig 5 .

Fig 5.

Summary of OR considerations for COVID-19 suspected or confirmed patients coming for emergency cardiac surgeries. PAPR: Powered air purifying respirator; PPE: Personal protective equipment; ESS: environment service staff.

Patient Care

The Division of Anesthesiology in SGH formed clinical care, infection control, and manpower allocation workgroups at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak to develop guidelines for the clinical management of suspected or confirmed cases.20 , 28 Guidelines and updates on what constitute aerosol-generating procedures also were regularly updated.

Discussion

The SARS outbreak infected 238 people and killed 33 in Singapore in 2003. Two in 5 of those infected were HCW.29 At that time, hospitals were overwhelmed and resources such as N95 masks and gloves were scarce.30 The authors pose the question, “Have we learned our lesson from the previous epidemic?”

Since the SARS outbreak, hospitals in Singapore have beefed up their infection control standards and management capabilities. The NCID with its state-of-the-art technology opened its doors in September 2019 for this very purpose.31 However, many of current HCW personally did not go through the SARS outbreak in their professional roles because it occurred more than a decade ago. The implementation of such measures therefore has been challenging for many. HCW across all departments have been sent to assist in the increased workload in the emergency department and isolation wards. Junior doctors are being excluded from performing surgery in order to reduce patient contact. Surgeons have had to work with fewer assistants in the OR.

We have also heard and read of colleagues who have sacrificed their time and lives during the SARS outbreak. Airway manipulation during anesthesia and other aerosol-generating procedures such as sternotomy and transesophageal echocardiography insertions are all high-risk activities performed on a daily basis. Although the calling to serve the community has never wavered, HCW want to provide the best level of care without compromising on personal safety.

Being a tertiary center for cardiothoracic referrals from other health care institutions also has posed unique challenges because of the potential risk of transferring an undiagnosed COVID-19 patient; therefore, workflow and interhospital transfers policies needed to be developed to reduce such risks, which occurred during SARS and in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. Currently, patients are only allowed to be transferred to NHCS after consultation with an infectious disease specialist and the heads of the cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery departments.

The advent of social media and the internet has allowed information, both true and false, to spread quickly and easily. This can be seen as an advantage but also may result in confusion and panic when incorrect information is disseminated. To combat fake news and maintain transparent risk communication, the SGH senior management provides its staff with daily updates regarding the current situation and introduced measures in line with the Ministry of Health. The Division of Anesthesiology also formed workgroups that provide regular updates on infection control and care of patients with suspected and confirmed COVID-19. Having such information at hand has provided a sense of calmness among HCW.

New plans are being made and updated as the situation unfolds with HCW adapting to new changes each day. HCW have stepped up when quarantine orders or leaves of absence were taken by their colleagues. Leave was cancelled voluntarily. Senior colleagues have helped guide their colleagues, and their advice has been crucial because they had first-hand experience of the SARS outbreak and were key to how rapidly workflows and guidelines were being implemented. Senior management personnel also were mindful that hospital services have expanded since SARS and that the cardiothoracic service required a larger operating space compared with the pre-COVID-19 era. It is to their credit that the change from room 3 to room 1 occurred within 2 days of feedback. Personal goggles and thermometers were supplied on short notice after suggestions were made. Teamwork, good communication across all departments, and willingness to listen are key components to maintaining good patient care, even in times of crisis.

Thankfully, although COVID-19 appears to be extremely infectious, at present, it does not seem to be as deadly as SARS. There had been no reported cases of local transmission from patient to HCW at the time of writing.

Although the authors have not performed surgery on any suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients, potential cases in the near future are anticipated given the second wave of infections originating from returning travelers.32 Through this article, the authors aimed to document some of the thought processes and difficulties they experienced to potentially help others who may find themselves in a similar situation.

Conclusion

In a difficult time, such as the present COVID-19 outbreak, there is limited time for elaborate planning and training. Despite the uncertainty and fear when the disease first appeared, the authors took on the challenges that were thrown at them one at a time. A clear direction from their leaders, confidence in their training, and great teamwork and spirit without compromising on personal safety played key roles in the rapid formulation of crisis plans and workflow.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all members of the Singapore General Hospital cardiothoracic anesthesia team and the surgeons, nurses, and perfusionists in the National Heart Centre Singapore for their ideas and suggestions as well as anesthetic technician Johari Bin Katijo for his excellent input and assistance.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in the writing of this article.

References

- 1.Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. Wuhan Municipal Commission of Health and Health on pneumonia of new coronavirus infection. Available at: http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2020012009077. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 2.Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. Wuhan Municipal Health and Health Commission's briefing on the current pneumonia epidemic situation in our city. Available at: http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 Feb 7 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [E-pub ahead of print], Accessed March 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui D.S., I Azhar E., Madani T.A. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health - the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92:401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation summary. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/summary.html. Accessed February 23, 2020.

- 9.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 30. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200219-sitrep-30-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6e50645_2. Accessed February 23, 2020.

- 10.World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) situation dashboard. Available at: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/685d0ace521648f8a5beeeee1b9125cd. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 11.World Health Organization. WHO director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 12.Department of Statistics Singapore. Tourism. Available at: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/industry/tourism/latest-data. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 13.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 19. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200218-sitrep-29-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6262de9e_2. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 14.Ministry of Health Singapore. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/newshighlights/details/confirmed-imported-case-of-novel-coronavirus-infection-in-singapore-multi-ministry-taskforce-ramps-up-precautionary-measures. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 15.Ministry of Health Singapore. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/confirmed-cases-of-local-transmission-of-novel-coronavirus-infection-in-singapore. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 16.Ministry of Health Singapore. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/risk-assessment-raised-to-dorscon-orange. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 17.Ministry of Communications and Information. What do the different DORSCON levels mean? Available at: https://www.gov.sg/article/what-do-the-different-dorscon-levels-mean. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 18.Tay J., Ng Y.F., Cutter J. Influenza A (H1N1-2009) pandemic in Singapore - public health control measures implemented and lessons learnt. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:313–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chee V.W., Khoo M.L., Lee S.F. Infection control measures for operative procedures in severe acute respiratory syndrome-related patients. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1394—8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong J., Goh Q.Y., Tan Z. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: A review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Can J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01620-9. [E-pub ahead of print], Accessed March 12, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liew M.F., Siow W.T., MacLaren G. Preparing for COVID-19: Early experience from an intensive care unit in Singapore. Crit Care. 2020;24:83. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2814-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phoon P.H.Y., MacLaren G., Ti L.K. History and current status of cardiac anesthesia in Singapore. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:3394–3401. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) or persons under investigation for COVID-19 in healthcare settings. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection control. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/environmental-guidelines-P.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 25.Chow T.T., Kwan A., Lin Z. Conversion of operating theatre from positive to negative pressure environment. J Hosp Infect. 2006;64:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/appendix/air.html#tableb1. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 27.Gralton J., Tovey E., McLaws M.L. The role of particle size in aerosolised pathogen transmission: A review. J Infect. 2011;62:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wax R.S., Christian M.D. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x. [E-pub ahead of print], Accessed March 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health Singapore. Available at:https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/resources-statistics/reports/cds2003.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2020.

- 30.Tan T.K. How severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) affected the department of anaesthesia at Singapore General Hospital. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32:394–400. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Health Singapore. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/speech-by-mr-gan-kim-yong-minister-for-health-at-the-official-opening-of-the-national-centre-for-infectious-diseases-on-saturday-7-september-2019-at-the-national-centre-for-infectious-diseases. Accessed February 23, 2020.

- 32.The Straits Times. Asia tries to fight a second wave of coronavirus cases sparked by travellers. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/asia-tries-to-fight-a-second-wave-of-coronavirus-cases-sparked-by-travellers. Accessed March 20, 2020.