Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To examine older adults’ use over time of agents to treat or prevent dementia or enhance memory.

DESIGN:

Longitudinal community study with ten-year annual follow-up (2006–2017).

SETTING:

Population-based cohort.

PARTICIPANTS:

A total of 1982 individuals with a mean (SD) age of 77 (7.4) years at baseline.

MEASUREMENTS:

Demographics, self-report, direct inspection of prescription anti-dementia drugs and non-prescription supplements, cognitive and functional assessments, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR®) Dementia Staging Instrument.

RESULTS:

Supplement use was reported by 27–42% of participants over ten years. Use was associated with younger age, high school or greater education, good to excellent self-reported health, higher memory test scores, and absence of cognitive impairment or dementia (CDR=0). Over the same period, about 2–6% of participants took prescription dementia medications over ten years. Use was associated with lower memory test scores, at least mild cognitive impairment (CDR≥0.5), fair to poor self-rated health, and high school or lesser education.

CONCLUSIONS:

The use of both prescription drugs and supplements increased over time, except for decreases in ginkgo and vitamin E. Prescription drug use appeared in line with prescribing guidelines. Supplement use was associated with higher education and better self-rated health; it persists despite a lack of supportive evidence.

Keywords: aging, pharmacoepidemiology, cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, supplements

INTRODUCTION

The FDA has approved several acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) to treat Alzheimer’s disease (AD): tacrine (1993), donepezil (1996), rivastigmine (2000), and galantamine (2001). The methyl-D-asparate receptor antagonist memantine was approved in 2004. Despite their modest effectiveness in controlled clinical trials among carefully selected trial participants1, questions remain about their risk:benefit ratio, particularly in advanced disease2. Current prescribing guidelines recommend limiting the use of AChEIs to treating mild to moderate AD dementia3.

Older adults’ fears of developing dementia4 may contribute to the burgeoning use of an array of unregulated dietary supplements (“nutraceuticals”): marketed to promote “brain health.” Despite absent evidence, older adults continue to purchase dietary supplements purported to boost memory, alertness, and/or stave off memory decline4. One meta-analysis showed only one third of supplement users disclosed their use to their physicians5. Sales of supplements for memory are projected to double between the years 2016 and 20236. Globally, the nutritional supplement market accounts for $82 billion US dollars, approximately 28% of which is attributed to American consumers7; the supplements promoting brain health are themselves a $3.2 billion worldwide market6. Concerns have been publicly expressed8, 9 about consumers taking unproven and unregulated treatments to prevent dementia or improve memory. Recently, the FDA issued a number of warning letters to companies selling supplements claiming to prevent, treat, or cure AD10.

Since 2006, we have been studying a population-based cohort of older adults in southwestern PA, with a focus on cognitive impairment and dementia. Here, we quantify and compare this cohort’s use, over ten years, of prescription drugs and non-prescription supplements for the treatment or prevention of cognitive decline.

METHODS

The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) cohort is an age-stratified sample of older adults, randomly drawn from the publicly available voter registration lists for a small-town, economically distressed, region of southwestern Pennsylvania, USA. Study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board for protection of human subjects. All participants provided written informed consent. Eligibility criteria were age 65+, decisional capacity, absence of severe vision or hearing impairment, and not living in long-term-care facilities at study entry (baseline). Between 2006 and 2008, 1982 newly recruited MYHAT participants, excluding those with substantial cognitive impairment at baseline, underwent detailed assessments by trained interviewers. Annually thereafter, surviving participants were invited to undergo re-assessment. The assessment included demographics, objective cognitive (neuropsychological) assessment, subjective cognitive concerns11, self-rated health, health history, and use of prescription and non-prescription drugs. Most assessments took place in participants’ homes. Further details have been reported previously12.

Medication History

At baseline and each follow-up assessment, participants were asked to show interviewers all the prescription and over-the-counter medications they were currently taking. Interviewers recorded medication names, dosage, and schedule from the bottle or package labels, and verified the details of medication use with participants. Interviewers asked participants their reasons for using non-prescription supplements, and who or what prompted them to take these products.

Neuropsychological Assessment

At each visit, participants were administered a neuropsychological test battery tapping several cognitive domains. Here we focus on memory tests (Fuld Object Memory Evaluation, the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory, and Visual Reproduction13, 14), creating for each participant a standardized composite memory score, first standardizing each individual test score and then calculating the mean of all the standardized scores in the memory domain.

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR®) Dementia Staging Instrument

At each visit, participants were rated on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR®) Dementia Staging Instrument15, 16. The CDR is based on the participant’s independence in cognitively-driven everyday activities and functions, such that CDR=0 indicates normal functioning or independence, CDR=0.5 indicates mild cognitive impairment (MCI); CDR ratings of 1, 2, and 3 indicate mild, moderate, and severe dementia.

Statistical Methods

Outcomes and Covariates.

The longitudinal outcomes reported here are the occurrence, over 10 annual assessments, of participants’ use of (a) prescription medications for dementia and (b) non-prescription memory supplements.

The covariates include age (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years), sex, education (less than high school, high school, and greater than high school), CDR (=0, =0.5, and ≥1), subjective cognitive concerns (≤2, 3–5, and >5), subjective health (poor/ fair, good, and very good/ excellent) and memory domain scores.

Descriptive statistics.

We examined covariate frequencies and proportions, stratified by the use of prescription medication/ memory supplements at each visit, and compared them between users and non-users of (a) prescription drugs, and (b) memory supplements. To detect overall group differences, we performed Chi-square tests. We also examined the recommendation sources reported by participants for each category of supplements.

Multivariable Models.

We fit generalized linear mixed models to assess the effect of time on the occurrence of using prescription medication/ memory supplements, adjusting for covariates. All models accounted for the random effects on intercept and time at individual levels.

We used data from all 1982 participants, except where missing observations were deleted from both descriptive analyses and multivariable models.

All analyses in this paper were conducted using SAS 9.417.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

At study entry (2006–2008), the 1982 participants had a mean baseline age (SD) of 77.6 (7.4) years (range 65–99 years). They were 61.1% female and 94.8% white, with 13.8%, 45.1%, and 41.1% completing less than high school, high school, and more than high school education. Only 1.6% of this Medicare-age population reported having no health insurance.

Prescription Medication Use

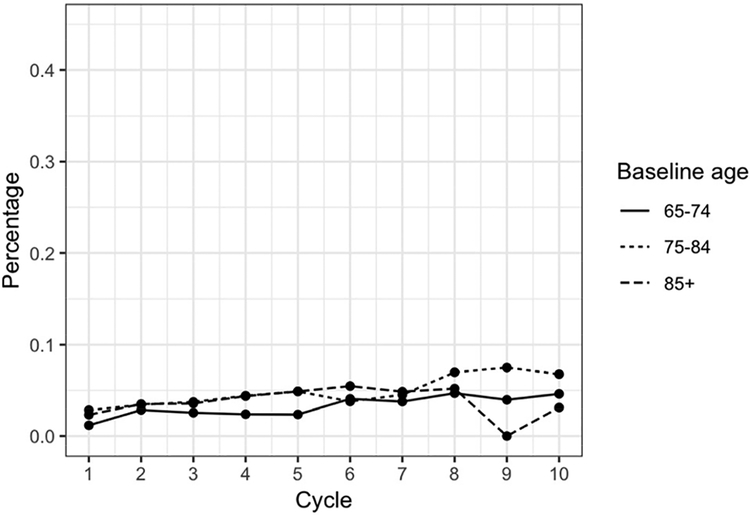

Over the first ten years of the MYHAT study, between 2.1% and 6.5% of study participants in any year reported taking one or more prescription drugs for dementia. Figure 1A shows drug use stratified by age at baseline.

Figure 1A. Dementia Drug Use Stratified by Age at Baseline.

Little difference in percent of use is seen between age groups at Year 1 (baseline), but by the end of the ten-year study period, the percentage of prescription dementia drug users is greatest in the middle age group (75–84) and lowest in the oldest age group (85+).

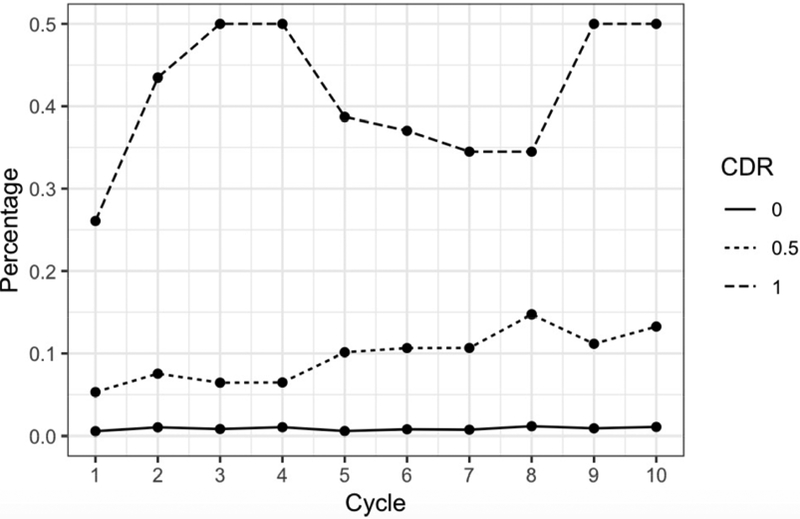

At baseline, 26.1% of participants with CDR≥1 reported taking dementia drugs, compared to 5.3% of those with CDRs of 0.5 and 0.6% of those with CDRs of 0. At the ten-year follow-up visit, the corresponding proportions were 50% of those with CDR≥1, 13.3% of those with CDR=0.5, and 1.1% % of those with CDR=0 (Figure 1C). Conversely, over the ten years, between 11% and 23% of dementia drug users were rated as CDR=0; between 45% and 68% as CDR=0.5; and between 14% and 38% of them as CDR≥1.

Figure 1C. Dementia Drug Use Stratified by Clinical Dementia Rating at Each Annual Assessment.

Of those with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 1 or greater, prescription dementia drug use ranged from 26% at baseline to 50% at year 10. For those with a CDR of 0.5, use increased from 6% to 13%; for people with a CDR of 0, use remained mostly stable with 0.6% at baseline and 1% at year 10.

Table 1 shows descriptive data from year 1 (baseline), year 5, and year 10; data from all years are shown separately (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1). Dementia drug use was associated with lower memory domain scores, at least mild cognitive impairment (CDR≥0.5), and fair to poor self-rated health.

Table 1.

Use of Prescription Medications for Dementia

| Study Cycle | 1 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Calendar Years | 2006–2008 | 2010–2012 | 2015–2017 | ||||

| N | 1982 | 1161 | 623 | ||||

| n (col %) | |||||||

| Individual prescription drugs for dementia | Donepezil | 36 (1.82) | 30 (2.6) | 25 (4.0) | |||

| Rivastigmine | 0 | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | ||||

| Galantamine | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 0 | ||||

| Memantine | 14 (0.71) | 20 (1.7) | 16 (2.6) | ||||

| Number of dementia drugs | 1 drug | 35 (1.77) | 34 (2.9) | 26 (4.1) | |||

| 2 drugs | 8 (0.4) | 11 (1.0) | 8 (1.3) | ||||

| Prescription drug Use | User | Non-User | User | Non-User | User | Non-User | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 43 (2.2) | 1939 (97.8) | 75 (6.5) | 1086 (93.5) | 34 (5.5) | 589 (94.5) | |

| Column % | |||||||

| Sex | Male | 53.5a | 38.6a | 42.2 | 36.7 | 35.3 | 35.0 |

| Female | 46.5a | 61.4a | 57.8 | 63.3 | 64.7 | 65.0 | |

| Education | < high school | 20.9 | 13.6 | 11.1 | 12.6 | 2.9 | 8.8 |

| = high school | 37.2 | 45.3 | 48.9 | 43.5 | 50.0 | 39.9 | |

| > high school | 41.9 | 41.1 | 40.0 | 43.9 | 47.1 | 51.3 | |

| Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) | CDR = 0 | 18.6c | 72.5c | 11.1c | 76.1c | 14.7c | 77.3c |

| CDR = 0.5 | 67.4c | 26.7c | 62.2c | 22.2c | 55.9c | 21.1c | |

| CDR ≥ 1 | 14.0c | 0.9c | 26.7c | 1.7c | 29.4c | 1.7c | |

| Age groupat study visit | 65–74 years | 18.6 | 34.7 | 15.6 | 26.2 | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| 75–84 years | 60.5 | 45.9 | 42.2 | 41.2 | 47.1 | 51.8 | |

| ≥ 85 years | 20.9 | 19.4 | 42.2 | 32.6 | 52.9 | 43.0 | |

| Subjective Memory Concerns (SMC) | ≤ 2 SMC | 37.5b | 64.3b | 17.1c | 68.3c | 30.3c | 68.9c |

| 3–5 SMC | 45.0b | 26.0b | 34.2c | 22.9c | 30.3c | 22.5c | |

| ≥ 6 SMC | 17.5b | 9.7b | 48.8c | 8.9c | 39.4c | 8.7c | |

| Objective impairment in memory domain* | Unimpaired | 26.5c | 93.6c | 48.8c | 90.5c | 48.4c | 89.5c |

| Impaired | 39.5c | 6.4c | 51.2c | 9.5c | 51.6c | 10.5c | |

| Self-rated health (SRH) | Poor/fair SRH | 20.9 | 17.4 | 28.9a | 16.1a | 17.7 | 13.1 |

| Good SRH | 51.2 | 45.6 | 53.3a | 46.7a | 55.9 | 55.8 | |

| Very good/excellent SRH | 27.9 | 37.1 | 17.8a | 37.2a | 26.5 | 31.1 | |

Memory test composite score <1.5 SD below mean

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Donepezil and memantine were the most frequently prescribed drugs. At each visit, some participants reported using more than one dementia drug (memantine plus either donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine). The odds of taking memantine increased by 15% every year (OR: 1.15, 95%CI: 1.02, 1.29, p = 0.018).

Non-Prescription Supplement Use

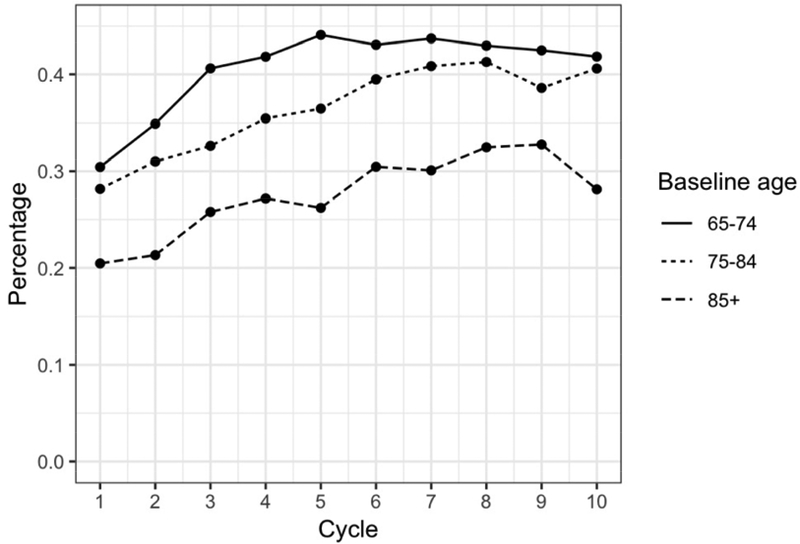

Over the same period, between 27% and 42% of participants in any year reported taking one or more supplements for memory/brain health; use was greater in younger age groups (Figure 1B).

Figure 1B. Supplement Use Stratified by Age at Baseline.

Over the ten-year study period, participants in the youngest age group (65–74 years) had the highest proportion of memory supplement users while the oldest age group (85+) had the lowest percentage of supplement use.

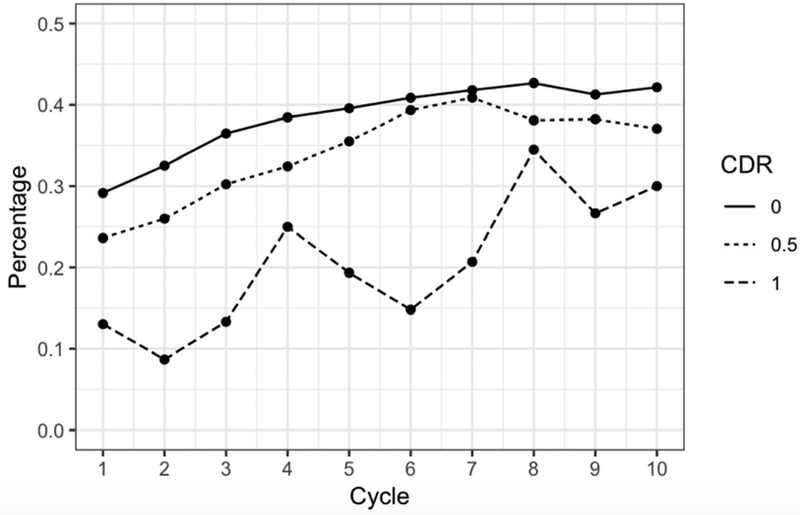

Supplement users were more likely to have high school or greater education than non-users. Table 2 shows descriptive data from year 1 (baseline), year 5, and year 10; data from all years are shown separately (see table, Supplemental Digital Content 2). At different study waves, supplement users were significantly more likely than non-users to have good to excellent self-reported health, higher memory test scores, and CDR=0. Figure 1D shows supplement use stratified by CDR at each annual assessment.

Table 2.

Use of Nutritional Supplements for Memory/Brain Health

| Study Cycle | 1 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Calendar Year | 2006–2008 | 2010–2012 | 2015–2017 | ||||

| N | 1982 | 1161 | 623 | ||||

| n (column %) | |||||||

| Individual Memory/brain Health Supplement | Antioxidant | 89 (4.5) | 78 (6.7) | 59 (9.5) | |||

| B12/Folicacid | 128 (6.5) | 105 (9.0) | 92 (14.8) | ||||

| NT Enhancer | 24 (1.2) | 10 (0.9) | 3 (0.5) | ||||

| Ginkgo | 44 (2.2) | 15 (1.3) | 4 (0.6) | ||||

| Multi-ingredient | 8 (0.4) | 8 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | ||||

| Omega 3 | 273 (13.8) | 305 (26.3) | 159 (25.5) | ||||

| Vitamin E | 236 (11.9) | 103 (8.9) | 34 (5.5) | ||||

| Other | 6 (0.3) | 11 (1.0) | 15 (2.4) | ||||

| Supplement Use | User | Non-User | User | Non-User | User | Non-User | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 533 (26.9) | 1449 (73.1) | 443 (38.2) | 718 (61.8) | 260 (41.7) | 363 (58.3) | |

| Column % | |||||||

| Sex | Male | 38.1 | 39.3 | 34.3 | 38.6 | 31.5 | 37.5 |

| Female | 61.9 | 60.7 | 65.7 | 61.4 | 68.5 | 62.5 | |

| Education | < high school | 9.9a | 15.2a | 9.9a | 14.2a | 6.2 | 10.2 |

| = high school | 46.7a | 44.5a | 41.5a | 45.0a | 44.2 | 37.7 | |

| > high school | 43.3a | 40.3a | 48.5a | 40.8a | 49.6 | 52.1 | |

| Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) | CDR = 0 | 75.6a | 69.7a | 76.3 | 71.9 | 78.1 | 70.8 |

| CDR = 0.5 | 23.8a | 28.9a | 22.1 | 24.8 | 19.6 | 25.3 | |

| CDR ≥ 1 | 0.56a | 1.4a | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.9 | |

| Age groupat study visit | 65–74 years | 37.9b | 33.0b | 30.3b | 23.0b | 3.5a | 6.1a |

| 75–84 years | 47.5b | 45.8b | 41.3b | 41.2b | 57.3a | 47.4a | |

| ≥ 85 years | 14.6b | 21.3b | 28.4b | 35.8b | 39.2a | 46.6a | |

| Subjective Memory Concerns (SMC) | ≤ 2 SMC | 65.8 | 63.1 | 70.8b | 63.8b | 69.8 | 64.7 |

| 3–5 SMC | 24.6 | 27.0 | 22.2b | 23.9b | 20.5 | 24.5 | |

| ≥ 6 SMC | 9.6 | 10.0 | 7.0b | 12.3b | 9.7 | 10.7 | |

| Objective impairment in memory domain* | Impaired | 94.7 | 92.2 | 91.4a | 87.5a | 89.3 | 85.8 |

| Unimpaired | 5.3 | 7.8 | 8.6a | 12.5a | 10.7 | 14.2 | |

| Self-rated health (SRH) | Poor/fair SRH | 15.6 | 18.1 | 13.5 | 18.5 | 10.8 | 15.2 |

| Good SRH | 45.0 | 46.0 | 47.0 | 46.9 | 60.0 | 52.8 | |

| Very good/excellent SRH | 39.4 | 35.9 | 39.5 | 34.5 | 29.2 | 32.0 | |

Abbreviations: NT, neurotransmitter

Memory test composite score <1.5 SD below mean

p<.05

p<.01

Figure 1D. Supplement Use Stratified by Clinical Dementia Rating at Each Annual Assessment.

Use of memory supplements increased over the course of the study for all CDR groups. Those with a CDR of 0 maintained the highest percentage of users over the ten-year period, while those with a CDR of 1 or greater had the lowest percentage of users.

At baseline, Omega 3/fish oil was the most frequently used supplement, followed by Vitamin E. We attempted to categorize the remaining products and ingredients based on their purported modes of action. Antioxidant products included astaxanthin, blueberry extract, coconut oil, Co-Q10, elderberry, ginseng, grape seed extract, noni, and selenium. Neurotransmitter enhancers included products containing bacopa, choline, l-carnitine, lecithin, phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylserine. Multi-ingredient products were those containing a mix of ingredients (for example, ginkgo, plus an antioxidant or a product containing several antioxidants and phosphatidylserine). The other category included colostrum, curcumin/turmeric, resveratrol, vinpocetine, and apoaquerin.

Reasons that participants provided for using these supplements included “general health”, “memory”, “heart function”, and “brain;” however, many respondents provided a rationale that mentioned non-CNS organ systems or no rationale at all. At baseline, 5.7% of individuals taking supplements stated they did not know why, similar to 5.4% of those taking prescription dementia drugs.

At baseline, 12 participants were taking both a dementia drug and a memory supplement. Over the course of ten years, a maximum of 58 individuals were at some point taking both.

In the multivariable models (Table 3), the odds of prescription drug use increased over time (p<0.001). Higher CDRs and lower memory domain scores were associated with use of these medications (p<0.001). In contrast, participants who were younger, more educated, and had higher memory domain scores had higher odds of using supplements. Overall, the odds of using supplements also significantly increased over time (Table 3); however, the use of ginkgo and vitamin E supplements declined (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Multivariable generalized linear mixed models of drug or supplement use

| Prescription Medication for Dementia | Supplements for Memory/ Brain Health |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Estimate | OR | SE | p | Estimate | OR | SE | p | |

| Intercept | −4.81 | 0.01 | 0.50 | <.0001 | −1.75 | 0.17 | 0.25 | <.0001 | |

| Assessment year | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.03 | <.0001 | 0.08 | 1.09 | 0.02 | <.0001 | |

| Education | HS vs. < HS | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.42 | 0.89 | 0.38 | 1.46 | 0.21 | 0.07 |

| > HS vs. < HS | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.43 | 0.84 | 0.56 | 1.75 | 0.22 | 0.01 | |

| Sex | Female vs. Male | −0.31 | 0.73 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 1.15 | 0.13 | 0.29 |

| Ageatbaseline | 75–84 vs. 65–74 | −0.2 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.41 | −0.21 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| ≥ 85 vs. 65–74 | −0.5 | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.12 | −0.38 | 0.69 | 0.16 | 0.02 | |

| Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) | CDR ≥ 1 vs. CDR = 0 | 1.82 | 6.16 | 0.42 | <.0001 | −0.43 | 0.65 | 0.39 | 0.26 |

| CDR = 0.5 vs. CDR = 0 | 1.14 | 3.13 | 0.25 | <.0001 | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.13 | 0.75 | |

| Subjective Memory Complaints (SMC) | SMC 3–5 vs. SMC ≤ 2 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.21 | 0.48 | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| SMC > 5 vs. SMC ≤ 2 | 0.26 | 1.3 | 0.27 | 0.33 | −0.10 | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.55 | |

| Memory domain composite score | −0.6 | 0.55 | 0.11 | <.0001 | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| Self-rated heath | Good vs. poor/fair | 0.21 | 1.23 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| Very good/excellent vs. poor/fair | 0.11 | 1.11 | 0.25 | 0.66 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.13 | 0.24 | |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; HS, high school

Vitamin B12 and Folate.

Over the ten years, 0.7% to 2.4% of participants took prescription Vitamin B12, while 3.7% to 12.5% took non-prescription B12 supplements. Prescription folic acid use ranged from 0.8% to 1.4%, while folic acid supplements, were taken by 2.7% to 4.3%. A prescription B12-folate combination (targeted at cognitive impairment) was reported by at most 2 participants (0.3%) in any given year.

Recommendation sources.

Participants identified physicians as their source for 20.7% of antioxidants, 19.5% of Vitamin B12/folic acid, 18.1% of Omega-3 products, and 14.5% of Vitamin E. They identified television and magazines as their source for 15.4% of antioxidants, 8.1% of Vitamin B, 12.0% of Omega-3 products, and 4.2% of Vitamin E (Table 4).

Table 4:

The sources which prompted participants to take memory supplements

| Antioxidant | Vitaminb12/ Folicacid |

NT Enhancer | Multi-ingredient | Ginkgo | Omega 3 | Vitamin E | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 169 | 343 | 37 | 22 | 58 | 564 | 289 | 34 |

| column % | ||||||||

| Physician | 20.7 | 19.5 | 16.2 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 18.1 | 14.5 | 20.6 |

| Friend/relative | 10.7 | 9.3 | 21.6 | 36.4 | 20.7 | 14.9 | 13.5 | 11.8 |

| Decided on own | 30.8 | 22.2 | 21.6 | 27.3 | 12.1 | 36.2 | 35.6 | 35.3 |

| TV/magazine | 15.4 | 8.2 | 21.6 | 22.7 | 22.4 | 12.1 | 18.0 | 20.6 |

| Others | 9.5 | 3.5 | 10.8 | 0 | 20.7 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 8.8 |

| Missing | 13.0 | 37.3 | 8.1 | 9.1 | 13.8 | 14.0 | 14.2 | 2.9 |

Abbreviations: NT, Neurotransmitter

DISCUSSION

Our study of nearly 2000 older adults living in a defined community provides an opportunity to describe trends in dementia drugs and memory supplements over the decade 2006–2017. To our knowledge, there have been no previous prospective investigations of simultaneous trends in both dementia prescription drugs and non-prescription memory-boosting supplements in population-based cohorts.

Trends in Prescription drugs for dementia.

Between 2006 and 2017, we found a modest increase (about 2% to 6%) in the use of prescription dementia drugs. This finding is as expected with the aging of the cohort and expected increasing prevalence of dementia at older ages. A more striking change was revealed at different CDR levels, with increasing proportions of those with CDR=0.5 (increasing from 5% to 13%) and CDR≥1 (from 26% to 50%) taking these drugs at the end of the observation period. Most (69–84%) participants taking dementia medication reported use of a single agent, but over the ten years, 16%-31% of participants reported taking the AChEI-memantine combination recommended for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease18. Participants taking these drugs had lower memory test scores and higher CDRs, suggesting that their use was consistent with prescribing guidelines19, 20.

Previous studies of dementia prescription drugs include a nationwide study of Medicare beneficiaries’ prescription fills during 2009;21 a retrospective cohort study using Medicare data from AD patients from 2008–2012;22 a retrospective analysis of persistence patterns in Spanish AD patients,23 and a Spanish pharmacy database.24 All studies showed the same broad patterns with donepezil being the most frequently taken, with memantine used more frequently in patients with moderate to severe dementia. One study22 found AChEIs being used alone in younger patients with mild dementia, then combined with memantine for patients with moderate dementia, and memantine alone in older patients with severe dementia. A UK study25 showed an apparent increased use of memantine in combination with an AChEI during 2005–2015.

Non-prescription supplements for memory support/ brain health.

In contrast, over the same ten-year period, a much larger proportion of our study participants reported taking over-the-counter supplements promoted as boosting brain health and supporting memory. This proportion increased from less than 30% at baseline to over 40% ten years later. Participants taking these supplements had better memory scores and fewer functional impairments typical of dementia, suggesting that they were taking them for prevention/maintenance rather than to treat perceived impairments. This finding was similar to that of overall supplement users in NHANES.4 However, a small minority of memory supplement users in MYHAT were also taking prescription dementia drugs, suggesting that they already had developed cognitive impairment.

The most commonly used supplements among our participants were Omega 3 fatty acids, vitamin E, and B12/folic acid. The same products were frequently reported in much larger National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study26 where 72% of adults over 65 reported taking supplements, and use increased with age. There is no evidence that any of these supplements prevent cognitive decline or dementia27, 28 and ginkgo was reported as ineffective starting in 200829–32. Like the NHANES group, we found a decline in the use of ginkgo biloba over the years of our study. Unlike NHANES, we examined trends in the use of both prescription dementia drugs and supplements over the same period. Further, our cohort was entirely aged 65+ years and provided data on several variables related to memory.

Some participants reported use of folic acid and vitamin B12, purchased with or without prescriptions, sometimes indicating that they were taking these products for memory. We have no data on how often these supplements were taken in response to a clinical indication or low blood levels. Supplementation with folic acid, with or without vitamin B12, has been proposed to reduce brain levels of homocysteine, but there is no evidence of their effectiveness in improving cognition.33

We have no obvious explanation for the increases in supplement use observed in this population-based cohort between 2006 and 2017. This data set does not lend itself to a classic age-period-cohort analysis to determine whether, in addition to an aging effect, there is also a period effect specific to this particular calendar decade. The fact that prescription dementia drug use remained largely stable during this period suggests that there was no dramatic increase in cognitive disorders. Among those who are cognitively healthy, demand for supplements may have increased as awareness of and fear of dementia increase4 perhaps in part spurred by public service messaging.34 Supply is certainly rising to meet demand; as noted earlier, “nutritional” supplements are a major growth industry6, 7 Possibly, suppliers may also be driving demand via increased direct-to-consumer marketing through mass media and social media35 Indeed, some of our participants reported recommendations for supplements coming from print and television media.

Other participants reported supplement recommendations that came from individuals known to them, including their physicians. As noted, Vitamin B12 and folate may have been recommended for documented deficiencies. We can speculate that some study participants may have heard about a specific memory supplement and asked their physicians’ opinions, or directly asked their physicians for recommendations for that or other supplements. Physicians may, for example, have suggested a vitamin or fish oil supplement, even in the absence of empirical evidence of benefit to the brain or to cognitive functions, on the grounds that these agents might provide general cardiovascular benefits. Some practitioners may consider it nihilistic to tell a patient that nothing can be done to improve memory and may find it preferable to recommend a harmless supplement instead. The fact that gingko and vitamin E use may have dropped off after the negative trial results were published30, 36 suggests that more independent trials of supplements may be useful to conduct and report. Until more trials are completed, documents such as The Global Council on Brain Health’s recent review of the benefits of dietary supplements may be a useful resource for both providers and consumers of health care.37

This being a large, prospective, population-based study, our results can be cautiously generalized to the type of economically depressed, small-town communities from which our cohort was drawn. Since it was not based on medical record linkage or claims databases, we do not have data to determine what agents participants’ providers prescribed or recommended, or pharmacy fill data to identify prescriptions that were or were not filled. Instead, our data were derived from participants’ self-reports, our examination of the bottle or package labels or medication lists, and participants’ perceived purpose of the products. Thus, our data are closer to reality regarding what older adults are actually taking, and what they understand about what they are taking, compared to what was prescribed but may or may not have been consumed as prescribed.

Our participants are older adults with some aging-related cognitive impairment, and small proportions of them have mild cognitive impairment or dementia. This fact allowed us to examine their medication and supplement use in relation to their cognitive status. However, impaired recall or poor health literacy could have influenced their understanding of their purpose of their medications and supplements. Some who responded that they took nothing for memory were in fact taking AChEIs, which is consistent with dementia being the reason that these drugs were prescribed for them. Those who stated they took their supplements for multiple reasons, e.g., “heart,” “memory,” “health,” made it difficult to determine whether they were using them for the advertised indications. We restricted our analyses to the subset of nutritional supplements that are promoted for “brain health”, “memory”, or “alertness”, and did not, for example, include multivitamin supplements that are not specifically advertised for these indications. Finally, since our study participants were mostly of European descent, representing older adults in our targeted communities, our findings should be replicated in other populations with larger proportions of ethnic minorities.

Our data show that only a small proportion of older adults at the population level are taking dementia prescription drugs; and they are doing so in a manner that appears broadly consistent with prescribing guidelines. However, a much larger proportion of younger, better educated, and healthier older adults is taking non-prescription supplements to support or enhance their brain health, despite lack of evidence to support the efficacy of these agents.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the MYHAT participants and the MYHAT project staff. They also thank Dr. Chung-Chou Chang for guidance on statistical analyses.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: Dr. Ganguli served on the “AD Patient Journey Working Group” for Biogen, Inc., in 2016 and 2017. All other authors have no conflicts to disclose. The work reported here was supported in part by research grant # R01 AG023651 from the National Institute on Aging, US DHHS

Sponsor’s Role: The National Institute of Aging had no role in the concept, design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Ganguli served on the “AD Patient Journey Working Group” for Biogen, Inc., in 2016 and 2017. All other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 148(5): 379–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deardorff WJ, Feen E, and Grossberg GT. The Use of Cholinesterase Inhibitors Across All Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs Aging. 2015; 32(7): 537–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien JT, Holmes C, Jones M, et al. Clinical practice withanti-dementia drugs: a revised (third) consensus statement from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2017; 31(2): 147–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Miller PE, et al. Why US adults use dietary supplements. JAMA Intern Med. 2013; 173(5): 355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019; 9(1): 1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Globalbrain health supplements marketan alysisand industry forecast 2017–2023, withan expected CAGR of 8.8% - ResearchAndMarkets.com.associated Press (online). June 28, 2018available at: https://www.apnews.com/bc428e8ecdea497b88c8b3e90fe98310. Accessed april 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teichner WLM. Cashing in on the booming market for dietary supplements. McKinsey & Company; December 2013Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/cashing-in-on-the-booming-market-for-dietary-supplements. Accessed January 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alternate Treatments. Alzheimer’s Association (online). Available at: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/alternative-treatments. Accessed april 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellmuth J, Rabinovici GD, and Miller BL. The Rise of Pseudomedicine for Dementia and Brain Health. JAMA. 2019; 321(6): 543–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on the agency’s new efforts to strengthen regulation of dietary supplements by modernizing and reforming FDA’s oversight. US Foodand Drug Administration; (online). February 11, 2019Available at: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm631065.htm. Accessed april 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snitz BE, Yu L, Crane PK, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints of older adults at the population level:an item response theory analysis. Alzheimer Disassoc Disord. 2012; 26(4): 344–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganguli M, Snitz B, Vander Bilt J, et al. How much do depressive symptoms affect cognitionat the population level? The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009; 24(11): 1277–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuld PA. Fuld Object-Memory Evaluation. Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting Instrument Company; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganguli M, Chang CC, Snitz BE, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment by multiple classifications: The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) project. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010; 18(8): 674–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current versionand scoring rules. Neurology. 1993; 43(11): 2412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAS [computer program]. Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons CG, Danysz W, Dekundy A, et al. Memantine and cholinesterase inhibitors: complementary mechanisms in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotox Res. 2013; 24(3): 358–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, et al. Recommendations of the 4th Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosisand Treatment of Dementia (CCCDTD4). Can Geriatr J. 2012; 15(4): 120–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winslowb T, Onysko MK, Stob CM, et al. Treatment of Alzheimer disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011; 83(12): 1403–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koller D, Hua T, and Bynum JP. Treatment Patterns with Antidementia Drugs in the United States: Medicare Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016; 64(8): 1540–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bent-Ennakhil N, Coste F, Xie L, et al. A Real-world Analysis of Treatment Patterns for Cholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine among Newly-diagnosed Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Neurol Ther. 2017; 6(1): 131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sicras-Mainar A, Vergara J, Leon-Colombo T, et al. [Retrospective comparative analysis of antidementia medication persistence patterns in Spanish Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine]. Rev Neurol. 2006; 43(8): 449–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calvo-Perxas L, Turro-Garriga O, Vilalta-Franch J, et al. Trends in the Prescription and Long-Term Utilization of Antidementia Drugs Among Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease in Spain: A Cohort Study Using the Registry of Dementias of Girona. Drugs Aging. 2017; 34(4): 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donegan K, Fox N,Black N, et al. Trends in diagnosis and treatment for people with dementia in the UK from 2005 to 2015:a longitudinal retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2017; 2(3): e149–e156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Du M, et al. Trends in Dietary Supplement Use Among US Adults From 1999–2012. JAMA. 2016; 316(14): 1464–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler M, Nelson VA, Davila H, et al. Over-the-Counter Supplement Interventions to Prevent Cognitive Decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Clinical Alzheimer-Type Dementia: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 168(1): 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forbes SC, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Poulin MJ, et al. Effect of Nutrients, Dietary Supplements and Vitamins on Cognition: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Can Geriatr J. 2015; 18(4): 231–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeKosky ST, Williamson JD, Fitzpatricka L, et al. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008; 300(19): 2253–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snitz BE, O’Meara ES, Carlson MC, et al. Ginkgo biloba for preventing cognitive decline in older adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009; 302(24): 2663–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon PR,Adams F, Silver A, et al. Ginkgo for memory enhancement: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 288(7): 835–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vellas B, Coley N, Ousset PJ, et al. Long-term use of standardised Ginkgo biloba extract for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (GuidAge):a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11(10): 851–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malouf R and Grimley Evans J. Folic acid with or without vitamin B12 for the prevention and treatment of healthy elderly and demented people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; (4): CD004514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devlin E, MacAskill S, and Stead M. ‘We’re still the same people’: Developing a mass media campaign to raise awareness and challenge the stigma of dementia. Int J Nonprofit Volunt Sect Mark. 2007; 1247–58. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donohue JM, Cevasco M, and Rosenthal MB. A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(7): 673–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dysken MW, Kirk LN, and Kuskowski M. Changes in vitamin E prescribing for Alzheimer patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009; 17(7): 621–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Health GCoB. The real deal on brain health supplements: GCBH recommendations on vitamins, minerals, and other dietary supplements. 2019. Available at: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/health/brain_health/2019/06/gcbh-supplements-report-english.doi.10.26419-2Fpia.00094.001.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.