Abstract

Purpose:

Adolescent handgun carrying is a behavioral marker for youth interpersonal conflicts and an intervention point for violence prevention. Our knowledge about the epidemiology of adolescent handgun carrying mainly pertains to urban settings. Evidence on the initiation age, cumulative prevalence, and longitudinal patterns of this behavior, as well as handgun-related norms and peer behavior among male and female rural adolescents is scant.

Methods:

We used data from the control arm of the Community Youth Development Study, a community-randomized controlled trial of the Communities That Care prevention system. Annually, 1039 males and 963 females were surveyed from Grade 6 (2005) to Age 19 (2012) in 12 rural towns across 7 U.S. states.

Results:

In Grade 6, 11.5% of males and 2.8% of females reported past-year handgun carrying. Between Grade 6 and Age 19, 33.7% of males and 9.6% of females reported handgun carrying at least once. Among participants who ever reported handgun carrying, 34.0% of males and 29.3% of females did so for the first time in Grade 6. Among participants who ever reported handgun carrying, 54.6% of males and 71.7% of females did so only 1 time over the 7 study assessments. Greater proportions of participants who reported handgun carrying than those who did not do so endorsed pro-handgun norms and had a peer who carried among both males (Grade 10-prevalence difference=57%; 95% CI:46%–67%) and females (Grade 10-prevalence difference=45%; 95% CI:12%–78%).

Conclusions:

Rural adolescent handgun carrying is not uncommon and warrants etiologic research for developing culturally-appropriate and setting-specific prevention programs.

Keywords: Firearms, Weapons, Adolescent, Rural Population, Female, Longitudinal Studies

Firearm injury is the second leading cause of death among individuals younger than 18 years in the U.S. with 65% of those deaths resulting from interpersonal violence [1]. Carrying firearms, especially handguns, is associated with adolescent bullying, physical fighting, and assault, and increases the chance of serious injury and death during such conflicts [2]. Adolescent handgun carrying is a behavioral marker that presents a clear violence intervention point [3] as suggested by findings of a randomized trial [4]. However, to develop effective preventive strategies, data on developmental features of handgun carrying, including age at initiation, age-specific and cumulative prevalence, and longitudinal patterns of this behavior over the course of adolescence are needed.

Much of prior evidence on adolescent handgun carrying is drawn from cross-sectional studies of males in urban areas. Only a few investigations of adolescent weapon (or gun or firearm) carrying with information on handguns have been longitudinal, and those too have mainly focused on males, criminal justice system-involved youth, or urban areas [2,5–7]. Rural male and female adolescents are largely understudied in this context, but they too are at risk of untoward health and social consequences of handgun carrying. The limited available evidence indicates that the prevalence of handgun carrying may actually be greater among rural than urban adolescents [8].

Prior studies have suggested a social normative influence in adolescent firearm carrying. Adolescents typically report that they were more likely to carry a firearm if other peers carried and that a common reason for carrying was “running into” other youth who carried”[9]. Considering peer norms could be an important component of interventions in communities. Similar to evidence on the initiation age and longitudinal patterns, much of the aforementioned information on firearm-related peer norms among adolescents comes from studies of males in urban areas. Data on handgun-related peer norms among male and female adolescents in rural areas are limited.

A recent comprehensive scoping review of the literature on adolescent firearm carrying found a striking dearth of information on all aspects of handgun carrying among rural adolescents [10]. Youth interpersonal violence rates (e.g., homicide, aggravated assault) are higher in several urban areas than in rural areas; however, that difference is not as large or generalizable as is widely assumed [11]. Youth in some rural areas experience higher rates of certain forms of interpersonal violence (e.g., being attacked or threatened with a weapon, picking a fight, and attacking someone or hurting them) than their counterparts in urban areas [12]. Rural adolescent handgun carrying is a potential behavioral indicator of involvement in youth interpersonal violence; however, we know little about its epidemiology.

To partially reduce these knowledge gaps, we used data from a large longitudinal study of rural adolescents to describe age at initiation, annual and cumulative prevalence, and longitudinal patterns of handgun carrying as well as handgun-related norms and peer behavior. Findings of this investigation add new and timely empiric evidence to the scant extant literature on rural adolescent handgun carrying and lay the groundwork for future etiologic research to inform violence prevention efforts in this population.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

Data came from a longitudinal panel of youth who were repeatedly surveyed as part of the Community Youth Development Study (CYDS), a community-randomized controlled trial of the Communities That Care (CTC) prevention system [13]. CYDS communities consisted of 24 small-to-moderate-sized towns with clear names and boundaries located in Washington, Oregon, Utah, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, and Maine. The communities had population sizes ranging from approximately 1,500 to 40,000 residents according to the 2000 U.S. Census, were not located in the suburbs of metropolitan areas, and were all classified as rural according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Business and Industry definition of being located outside of Census places with a population of ≥ 50,000 people [14]. Communities were matched in pairs within each state on population size, racial and ethnic diversity, economic indicators, and crime rates, and randomized to the experimental or control condition in 2003 [13]. For the purpose of the present study, we used data from the 12 control communities (hereafter: “study communities”) to avoid confounding by intervention effects. Prior analyses of CYDS youth panel data showed that CTC significantly improved a range of youth behavioral health outcomes, including reductions in substance use [15] as well as delinquency and violence [16] into young adulthood.

The study communities had an average population of 14,222 (range: 2,084–33,870) and varied in rurality and proximity to urban areas [17]. Based on the geographic taxonomy of the ZIP code approximation of the Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) [18,19], one of the study communities was classified as a small rural town, seven as large rural towns, and four as urban-focused towns. Although the urban-focused communities had high commuting flows to urbanized areas, they were similar in population size to the large rural towns; the average population in both was about 15,000. Economically, four of the communities were primarily dependent on manufacturing, three on nonspecialized industries, two on federal and state government, two on mining, and one on service [19].

Study Population

The youth panel was recruited in the fall of 2003 from the cohort of students in Grade 5 attending public schools in the study communities. Recruitment continued into Grade 6 to increase study participation. Parents of 77.0% (n=2,010) of those eligible in the study communities consented to their child’s participation. The students who completed a Grade 5 (Wave 1) or Grade 6 (Wave 2) survey and remained in their communities for at least one semester (n=2,002) comprised the longitudinal study panel (hereafter: “participants”) [20]. Participants were followed regardless of where they moved or whether they were still in school. Annual surveys were completed from Grade 6 (in 2005) to Age 19 (in 2012), except in Grade 11, by more than 90% of participants each year including 91.0% at Age 19.

Measures

Instrument

In Grades 5–12, participants completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire during a class period. After high school, the questionnaire was offered online or mailed. All the questionnaires were based on the CTC Youth Survey which provides reliable and valid self-report measures of community, family, school, peer, and individual norms and other risk and protective factors, as well as drug use, delinquency, violence, and other behavioral health outcomes [21]. Participants received completion incentives of $5–$10 through Grade 12 and $25 at Age 19. The University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee approved this protocol.

Handgun Carrying

Each year from Grade 6 to Age 19, the survey asked: “How many times in the past year (12 months) have you carried a handgun?” Response options were ordinal categories: Never, 1–2 times, 3–5 times, 6–9 times, 10–19 times, 20–29 times, 30–39 times, and 40 or more times. Age at initiation of handgun carrying was based on the first assessment during which participants reported carrying a handgun in the past year. Annual prevalence of handgun carrying was based on the self-report of this behavior in the past year at each assessment (0: did not carry a handgun in the past year; 1: carried a handgun at least once in the past year). Cumulative prevalence of handgun carrying was based on all self-reports of this behavior up to each assessment (0: never reported handgun carrying up to that assessment; 1: reported handgun carrying in the past year or at least once previously).

Handgun-Related Norms and Peer Behavior

Beginning in Grade 7, the survey also asked about handgun-related norms and handgun carrying by peers. Data obtained based on these questions were dichotomized based on clear distinctions in the prevalence of certain responses to each question observed empirically. Personal norms were measured by asking: “How wrong do you think it is for someone your age to take a handgun to school or work?” Responses were grouped into 0 denoting “Very wrong” vs. 1 denoting “Wrong”, “A little bit wrong”, or “Not wrong at all”. Perceived peer norms were measured by asking: “What are the chances you would be seen as cool if you carried a handgun?” Responses were grouped into 0 denoting “No or very little chance”, “Little chance”, or “Some chance” vs. 1 denoting “Pretty good chance” or “Very good chance”. To assess handgun-related peer behavior, participants were asked: “In the past year (12 months), how many of your best friends have carried a handgun?” Youth were instructed to think of friends to whom they felt closest. Response options were “None”, “1 of my friends”, “2 of my friends”, “3 of my friends”, and “4 of my friends”. Responses were grouped into 0 denoting no friends and 1 denoting one or more friends.

Statistical Analysis

Age at self-reported first handgun carrying, annual prevalence of handgun carrying in the past year, and cumulative prevalence of handgun carrying across adolescence from Grade 6 to Age 19 were separately described among males and females. Differences in the prevalence of handgun-related norms and peer behavior by self-reported handgun carrying status during the past year at each assessment were separately determined among males and females. The 95% confidence intervals for prevalence differences were constructed using the binomial distribution.

RESULTS

Participants were on average 12 years old in Grade 6. About 48.1% were female and 73.4% self-identified as non-Hispanic (or non-Latino/a); 79.0% of participants were White and the highest level of educational attainment for 34.1% of parents was high school or less (Table 1). There were high degrees of consistency in the rurality of former and current residence among participants who moved, and little missing data in this investigation (Supplementary Materials).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants in the 12 CYDS control communities (n=2,002)

| Characteristic | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Residence urbanicity | ||

| Urban-focused town | 828 | 41.4 |

| Large rural town | 1085 | 54.2 |

| Small rural town | 89 | 4.4 |

| Female | 963 | 48.1 |

| White | 1,582 | 79.0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 1,470 | 73.4 |

| Highest level of parent’s educationa | ||

| Completed high school or less | 654 | 34.1 |

| Some college | 466 | 24.3 |

| Completed college | 555 | 29.0 |

| Graduate or professional school | 242 | 12.6 |

CYDS: Community Youth Development Study

Highest level of parent’s education was missing for 85 participants.

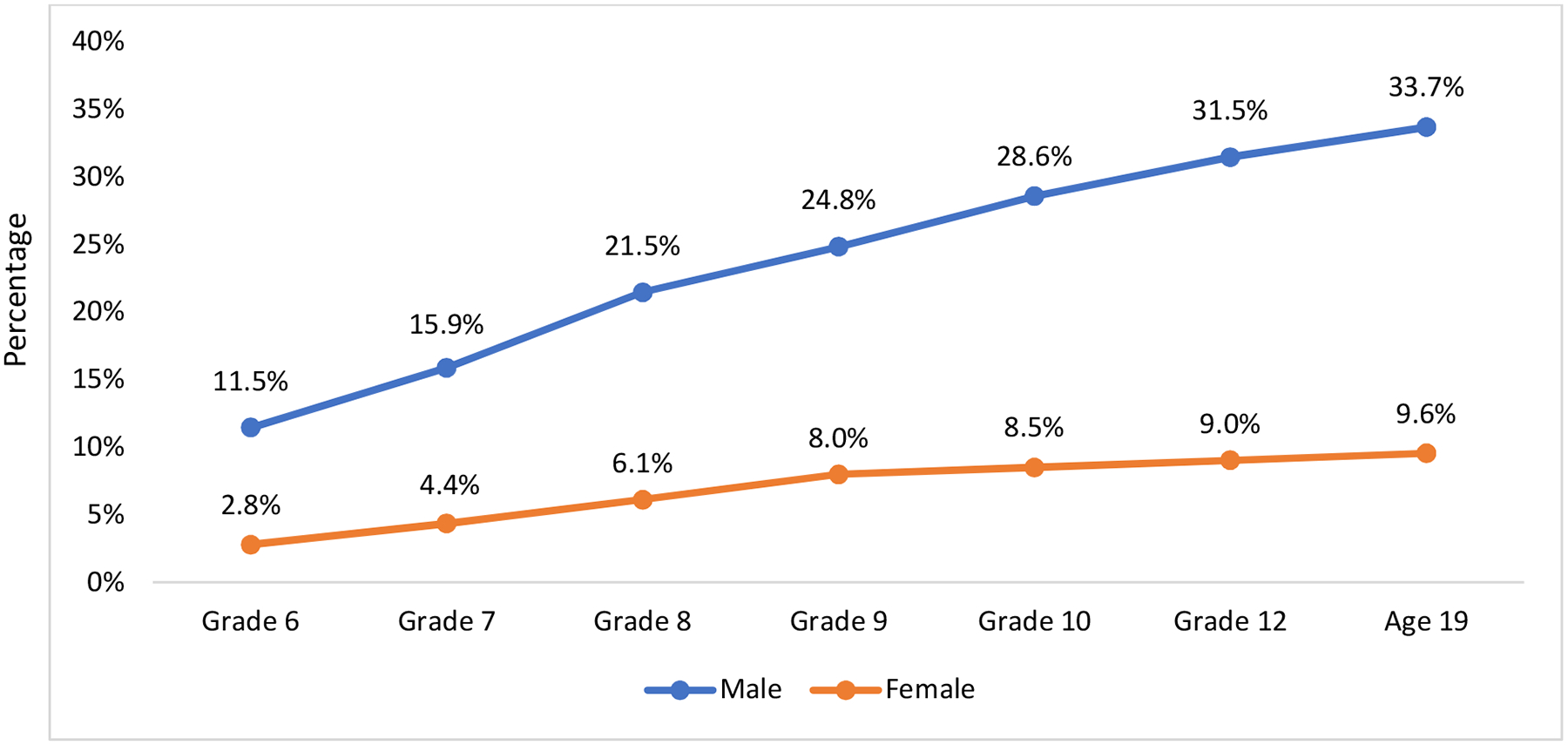

In Grade 6, 11.5% of males and 2.8% of females reported handgun carrying in the past year (Table 2). The cumulative prevalence of handgun carrying had increased several-fold by Age 19, with the steepest increase occurring between Grade 6 and Grade 8 (Figure 1). Between Grade 6 and Age 19, 22.1% (n=442) of participants including 33.7% (n=350) of males and 9.6% (n=92) of females reported handgun carrying at least once (Figure 1). Across assessments, annual prevalence of handgun carrying was relatively stable at about 9%–12% for males and 1%–3% for females at any grade or age (Table 2). Among participants who ever reported handgun carrying, 34.0% of males and 29.3% of females did so for the first time in Grade 6 (Table 2). Among participants who ever reported handgun carrying, 54.6% of males and 71.7% of females did so only 1 time over the 7 assessments (Figure 2). Among participants who ever reported handgun carrying, only 5.4% did so at 5 or more of the 7 assessments. Only 3 males and no females reported carrying at all 7 assessments. Among participants who ever reported carrying a handgun, the maximum frequency of that behavior in the past year was 1–2 times for 44% of males and 61% of females (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 2.

Past-year handgun carrying by grade/age and sex

| A. Annual prevalence of past-year handgun carrying at each assessment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | Grade 7 | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | Grade 12 | Age 19 | |

| Males (n=1,039)a | 119 (11.5) | 89 (9.0) | 110 (11.2) | 87 (9.0) | 94 (10.0) | 81 (9.1) | 83 (9.4) |

| Females (n=963)b | 27 (2.8) | 19 (2.1) | 25 (2.7) | 26 (2.8) | 12 (1.3) | 14 (1.5) | 13 (1.4) |

| B. Distribution of first reporting of past-year handgun carrying among ever reporters | |||||||

| Grade 6 | Grade 7 | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | Grade 12 | Age 19 | |

| Males (n=350) | 119 (34.0) | 46 (13.1) | 58 (16.6) | 35 (10.0) | 39 (11.1) | 30 (8.6) | 23 (6.6) |

| Females (n=92) | 27 (29.3) | 15 (16.3) | 17 (18.5) | 18 (19.6) | 5 (5.4) | 5 (5.4) | 5 (5.4) |

Note. Numbers shown in the table are n (%).

Total number of respondents at some assessments is fewer than 1,039.

Total number of respondents at some assessments is fewer than 963.

Figure 1.

Cumulative prevalence of past-year handgun carrying by sex

Figure 2.

Number of assessments in which past-year handgun carrying was reported among ever reporters by sex

Compared to participants who never reported handgun carrying, notably greater proportions of those who reported handgun carrying also reported favorable personal norms toward handgun carrying, perceived their friends to have favorable norms toward handgun carrying, and had close friends who carried handguns (Figure 3). For example, 63% of males who reported handgun carrying in Grade 10 had a close friend who had carried a handgun compared to only 6% of males who did not report handgun carrying (prevalence difference: 57%; 95% CI: 46%–67%). Similarly, 50% of females who reported handgun carrying in Grade 10 had a close friend who had carried a handgun compared to only 5% of females who did not report handgun carrying (prevalence difference: 45%; 95% CI: 12%–78%). These large differences in the prevalence of handgun norms and peer behavior by self-reported handgun carrying status did not substantially vary across adolescence among either male or female participants (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Among participants who ever reported that any of their close friends had carried a handgun in the past year, 39% of males and 51% of females reported a maximum of only 1 such friends at any assessment (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Norms toward handgun carrying and peer handgun carrying by self-reported past-year handgun carrying status and sex

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is one of the first multi-state longitudinal studies of rural adolescent handgun carrying in the U.S. We found that about 1 in 3 males and 1 in 10 females had carried a handgun at least once from Grade 6 to Age 19. Among those who reported carrying at least once, about 1 in 3 adolescents did so in Grade 6. There were striking differences between respondents who carried and those who did not carry in terms of handgun norms and peer behavior. These findings provide an anchor point for future investigations to identify risk and protective factors associated with handgun carrying and identify opportunities for preventing violence victimization and perpetration among rural adolescents.

The U.S. federal law bars youth under age 18 from possessing a handgun [22]. National data, however, indicate that a sizeable number of U.S. adolescents carry handguns illegally. One national survey that routinely measures adolescent gun carrying is the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) administered to thousands of adolescents in Grades 9–12. In 2017, 4.8% of adolescents (7.7% of males and 1.9% of females) participating in YRBSS reported having carried a gun in the past year [23]. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found a prevalence of 4.6% (6.8% of males and 2.4% of females) for past-year handgun carrying among adolescents aged 12–17 in 2017 [24]. Handgun carrying was especially prevalent among adolescents in non-metro areas (7.2%) compared to those in small metro (5.4%) and large metro areas (3.6%), with youth in completely rural areas reporting the highest prevalence (12.3%).

Most sub-national studies of adolescent firearm carrying in urban settings have identified recent (past 12-month, 6-month, or 30-day) prevalence of about 5%–10%, and cumulative prevalence of about 15%–20% [10]. A study that measured past-year handgun carrying to school among Grade 8–10 students in rural areas found the prevalence of that behavior to be about 10% [25]. Our estimates of the annual and cumulative prevalence of handgun carrying suggest that a notable number of rural youths carry a handgun at least once over adolescence. While female adolescents are less likely than males to carry a handgun, national data suggest that the frequency of this behavior may be increasing among them [24]. Our study provides new information on the frequency of this behavior among female adolescents in rural areas and facilitates further research into motivations, risk and protective factors, and consequences of handgun carrying specifically among this group of youth.

The NSDUH data also suggest that younger adolescents (3.0% of those aged 12–13 years) are less likely to carry a handgun than older adolescents (5.9% of those aged 16–17 years). While evidence on the age at initiation and longitudinal patterns of adolescent handgun carrying in diverse urban areas is limited, it is virtually non-existent in rural areas. The few studies that have examined these characteristics in urban areas have generated different results due to heterogeneity in definitions, timeframes used to examine trajectories, and study populations [2,5,26–30]. For example, using data from the urban sample of National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997, Dong et al. found the mean age at initiating handgun carrying to be 18.2 years (males: 17.8 years; females: 19.4 years) [2]. The mean age at initiation of firearm carrying has been found to be lower among certain high-risk youth such as adolescents involved in criminal justice systems, those exposed to neighborhood violence, and those with certain behavioral disorders [3,5]. Our finding that about a third of youth who carried a handgun reported doing so in Grade 6 highlights the importance of early prevention programs among rural adolescents.

We found that a majority of rural adolescents reported handgun carrying only once, and those who reported more than once did so episodically. Most of prior studies of firearm carrying among urban adolescents have considered persistent or continuous carrying as one that extended beyond 1–2 waves of annual data collection with intermittent or episodic carrying defined as lasting fewer than 1–2 years of adolescence. Most of those studies found that a majority (about 50%–70%) of adolescents reported carrying only at one timepoint, with a minority reporting carrying at two or more waves, and a much smaller fraction reporting at all waves [2,5,28–31]. This evidence indicates that urban adolescent firearm carrying is an intermittent, and not persistent, behavior. Our findings on the longitudinal patterns of rural adolescent handgun carrying are consistent with those observations in urban areas. Future research to discern different subgroups of rural adolescent handgun carriers based on duration of carrying is important as such qualitative distinction may shed light on specific motivations, risk and protective factors, and consequences of this behavior in each of these subgroups as done in urban areas [32].

We found striking differences in handgun-related norms and peer behavior between rural adolescents who ever carried a handgun and those who did not; the differences were robust across all grades over adolescence and observed among both males and females. These results are important as they enhance our understanding of factors beyond the individual level that may have a bearing on rural adolescent handgun carrying. Earlier studies in urban areas have found peer gun ownership, carrying, and delinquency as well as perceived norms about firearms to be associated with firearm carrying [33–37]. Firearm carrying creates “replicative externalities” where one action increases the likelihood that similar actions will occur [9]. Handgun carrying by peers and the perception of that behavior being “cool” may increase the likelihood that others will also carry handguns. Perceived norms have a powerful effect on many social behaviors; youth who overestimate the prevalence of risky behaviors by their peers engage in such activities more often than those who estimate norms more accurately [33]. As such, prevention programs that help students more accurately assess firearm carrying by their peers may allow them to adjust their sense of social norms around this behavior and make a more accurate assessment of its “cost-benefit” [9].

This study is subject to some limitations. First, the survey did not ask to where the respondents carried a handgun (e.g., school, neighborhood), from whom they obtained it (e.g., family, friend), how they obtained it (e.g., purchasing, renting), and why they carried it (e.g., self-defense, retaliation). Since the handgun-related questions were all placed in the section of the survey that sought information on problem behavior and violence, the adolescents may not have responded to the question on the frequency of handgun carrying affirmatively if they had carried handguns for recreational or sporting purposes only. Second, the response options for that question did not include “1 time” (it was “1–2 times”); as such, we were unable to quantify the proportion of respondents who carried exactly one time. Third, since our first assessment of past-year handgun carrying took place in Grade 6, we cannot be certain that it began during that year (and not earlier) among those who endorsed it at that wave. Fourth, sample sizes for racial groups were too small to provide statistically stable race-specific estimates. Fifth, communities studied are not representative of the entire country, specific regions, or certain states. They were chosen based on data indicating that none of them were using tested and effective preventive measures to address prioritized community risks. Sixth, as in other self-report-based surveys, the possibility of bias (e.g., social desirability) cannot be ruled out. However, based on our prior analyses of CYDS data, we have found the extent of reporting certain behaviors (e.g., drug use) to be very similar to that of the same cohort in the Monitoring the Future survey mitigating concerns about potential mismeasurement of the frequency of problem behaviors.

Youth firearm violence is often presented as an inner-city problem among males. However, this emphasis on urban areas should not come at the cost of ignoring male and female adolescents in rural areas. It is imperative to take distinct cultural, social, and environmental features of rural areas into consideration to enhance the effectiveness of tailored prevention strategies among youth in those settings. Among gun-owning rural Americans, 47% became firearm owners before they turned 18 in contrast with 27% of their counterparts in urban communities [38]. As part of socialization into rural areas’ gun culture (e.g., hunting), receiving a long-gun in adolescence is seen as a rite of passage to adulthood [39]. However, little is known about the specific role of handguns in these settings’ social relations. Social disorganization theory posits that factors such as residential instability stemming from poverty can affect a community’s capacity to maintain strong systems of social relations and prevent urban youth violence. However, this urban population dynamic does not exist in many rural areas; outside the city, the populations of poorer communities may actually be more stable than average, not less [11].

Reducing adolescent firearm carrying is among the key national health objectives outlined in Healthy People 2020 [40]. Given that adolescence is a developmental period characterized by unique risk and protective factors and that underlying social and cultural factors related to handgun carrying may differ based on the setting, additional research on causes, correlates, and consequences of this behavior among rural adolescents is warranted.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

In this longitudinal study of rural adolescents, about 1 in 3 males and 1 in 10 females reported carrying a handgun at least once. Among ever carriers, about 1 in 3 adolescents had already done so in Grade 6. Findings inform violence prevention programs among rural adolescents.

Acknowledgments:

Parts of the findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, Washington, DC, May 30, 2018, and the annual symposium of the Firearm Safety Among Children and Teens Consortium, Ann Arbor, MI, October 21, 2019.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01DA015183, R56DA044522, and R01DA044522, with co-funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Abbreviations

- U.S.

United States

- CYDS

Community Youth Development Study

- CTC

Communities That Care

- YRBSS

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

- NSDUH

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01088542

REFERENCES

- [1].Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The Major Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med 2018;279:2468–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dong B, Wiebe DJ. Violence and beyond: Life-course features of handgun carrying in the urban United States and the associated long-term life consequences. J Crim Justice 2018;54:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Spano R, Pridemore WA, Bolland J. Specifying the role of exposure to violence and violent behavior on initiation of gun carrying: a longitudinal test of three models of youth gun carrying. J Interpers Violence 2012;27:158–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zatzick D, Russo J, Lord SP, et al. Collaborative care intervention targeting violence risk behaviors, substance use, and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in injured adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:532–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Loeber R, Burke JD, Mutchka J, et al. Gun Carrying and Conduct Disorder: A Highly Combustible Combination? Implications for Juvenile Justice and Mental and Public Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lizotte AJ, Tesoriero JM, Thornberry TP, et al. Patterns of adolescent firearms ownership and use. Justice Q 1994;11:51–74. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Simon TR, Richardson JL, Dent CW, et al. Prospective psychosocial, interpersonal, and behavioral predictors of handgun carrying among adolescents. Am J Public Heal 1998;88:960–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Series. Available at: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/64. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- [9].Hemenway D, Prothrow-Stith D, Bergstein JM, et al. Gun carrying among adolescents. Law Contemp Probl 1996;59:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Oliphant SN, Mouch CA, Rowhani-Rahbar A, et al. A scoping review of patterns, motives, and risk and protective factors for adolescent firearm carriage. J Behav Med 2019;42:763–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Osgood DW, Chambers JM. Community correlates of rural youth violence. Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. 2003;5:1–12. Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/193591.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Murphy J Comparing rural and urban drug use and violence in the Pennsylvania Youth Survey. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania. Available at: https://www.rural.palegislature.us/documents/reports/PAYS-2018.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- [13].Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, et al. Testing communities that care: the rationale, design and behavioral baseline equivalence of the community youth development study. Prev Sci 2008;9:178–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Rural Definitions: Data Documentation and Methods. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-definitions/data-documentation-and-methods. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- [15].Oesterle S, Hawkins JD, Kuklinski MR, et al. Effects of Communities That Care on Males’ and Females’ Drug Use and Delinquency 9 Years After Baseline in a Community-Randomized Trial. Am J Community Psychol 2015;56:217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oesterle S, Kuklinski MR, Hawkins JD, et al. Long-term effects of the communities that care trial on substance use, antisocial behavior, and violence through age 21 years. Am J Public Health 2018;108:659–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].United States Census. City and Town Intercensal Datasets: 2000–2010. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/intercensal-2000-2010-cities-and-towns.html. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- [18].Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM, et al. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Center for Rural Health. University of North Dakota. ZIP RUCA 3.10 file access page. Available at: https://ruralhealth.und.edu/ruca. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- [20].Brown EC, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW, et al. Design and analysis of the Community Youth Development Study longitudinal cohort sample. Eval Rev 2009;33:311–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Glaser RR, Horn ML Van, Arthur MW, et al. Measurement properties of the Communities That Care® Youth survey across demographic groups. J Quant Criminol 2005;21:73–102. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Minimum Age to Purchase & Possess. Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. Available at: https://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/who-can-have-a-gun/minimum-age/#federal. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- [23].Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67:1–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Detailed Tables, 2017. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2017-nsduh-detailed-tables. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- [25].Kingery PM, Pruitt BE, Heuberger G. A profile of rural Texas adolescents who carry handguns to school. J Sch Health 1996;66:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Arria AM, Wood NP, Anthony JC. Prevalence of carrying a weapon and related behaviors in urban schoolchildren, 1989 to 1993. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:1345–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Beardslee J, Mulvey E, Schubert C, et al. Gun-and Non-Gun–Related Violence Exposure and Risk for Subsequent Gun Carrying Among Male Juvenile Offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;57:274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lizotte AJ, Howard GJ, Krohn MD, et al. Patterns of illegal gun carrying among young urban males. Valparaiso Univ Law Rev 1997;31:375. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Reid JA, Richards TN, Loughran TA, et al. The relationships among exposure to violence, psychological distress, and gun carrying among male adolescents found guilty of serious legal offenses: a longitudinal cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:412–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Steinman KJ, Zimmerman MA. Episodic and persistent gun-carrying among urban African-American adolescents. J Adolesc Heal 2003;32:356–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sheley JF. Drugs and guns among inner-city high school students. J Drug Educ 1994;24:303–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dong B, Jacoby SF, Morrison CN, et al. Longitudinal Heterogeneity in Handgun-Carrying Behavior Among Urban American Youth: Intervention Priorities at Different Life Stages. J Adolesc Heal 2018;64:502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hemenway D, Vriniotis M, Johnson RM, et al. Gun carrying by high school students in Boston, MA: does overestimation of peer gun carrying matter? J Adolesc 2011;34:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Howell JC, et al. Factors influencing gun carrying among young urban males over the adolescent-young adult life course. Criminology 2000;38:811–34. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sheley JF, Brewer VE. Possession and carrying of firearms among suburban youth. Public Heal Rep 1995;110:18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Beardslee J, Docherty M, Mulvey E, et al. Childhood risk factors associated with adolescent gun carrying among Black and White males: An examination of self-protection, social influence, and antisocial propensity explanations. Law Hum Behav 2018;42:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Luster T, Oh SM. Correlates of male adolescents carrying handguns among their peers. J Marriage Fam 2001;63:714–26. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Igielnic R Rural and urban gun owners have different experiences, views on gun policy. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/07/10/rural-and-urban-. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- [39].Yamane D The sociology of U.S. gun culture. Sociol Compass 2017;11:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Healthy People 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed August 23, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.