Abstract

A promising new compound class for treating human malaria is the imidazolopiperazines (IZP) class. IZP compounds KAF156 (Ganaplacide) and GNF179 are effective against Plasmodium symptomatic asexual blood-stage infections, and are able to prevent transmission and block infection in animal models. But despite the identification of resistance mechanisms in P. falciparum, the mode of action of IZPs remains unknown. To investigate, we here combine in vitro evolution and genome analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae with molecular, metabolomic, and chemogenomic methods in P. falciparum. Our findings reveal that IZP-resistant S. cerevisiae clones carry mutations in genes involved in Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)-based lipid homeostasis and autophagy. In Plasmodium, IZPs inhibit protein trafficking, block the establishment of new permeation pathways, and cause ER expansion. Our data highlight a mechanism for blocking parasite development that is distinct from those of standard compounds used to treat malaria, and demonstrate the potential of IZPs for studying ER-dependent protein processing.

Subject terms: Endoplasmic reticulum, Target identification

Imidazolopiperazines (IZPs) are a class of compounds under clinical development for malaria, but their mechanism of action is unclear. Here, the authors show that IZPs inhibit the parasite’s secretory pathway, affecting protein trafficking and export.

Introduction

Malaria remains the most common human parasitic disease, sickening an estimated 219 million people annually and causing an estimated 435,000 deaths worldwide1. Although a reduction in the malaria burden has been achieved through the combined use of public health infrastructure, vector control, and increased access to medical treatment2,3, these efforts are hindered by a variety of factors, such as the lack of an effective vaccine, increased mosquito resistance to pesticides, and the continuing emergence of drug-resistant parasite strains4–6. Currently, resistance has been reported against nearly all classes of antimalarial compounds deployed in the field such the quinoline-type drugs (i.e. chloroquine, mefloquine, amodiaquine etc), antifolates (sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine), and naphthoquinones (atovaquone)7–9. And perhaps most alarming of all, resistance against the endoperoxide artemisinin—a central component of malaria control programs worldwide—is also emerging10. Given that an estimated 3.2 billion people live in endemic regions and are at risk for malaria3, new classes of antimalarial compounds will be required to combat and ultimately eradicate this disease.

One of the most promising classes of compounds are the imidazolopiperazines (IZPs), such as KAF15611 and its closely related analog GNF17912, which differs from KAF156 by a single halogen substitution (F to Cl). The chemotype that led to KAF156 was first identified in a phenotypic screen designed to discover compounds with activity against parasite asexual blood stages13. The compound series attracted more attention when it was noted that multiple analogs were present in the library, which all showed activity in a liver stage model that predicts causal antimalarial prophylaxis12. Subsequent rounds of medicinal chemistry14,15 led to the development of KAF156, an orally available, simple-to-synthesize compound suitable for testing in humans11.

KAF156 shows potent activity against asexual blood (IC50 ~ 6 nM), hepatic (IC50 = 4.5 nM) and sexual stages (IC50 = 5 nM)11, and is considered safe with good pharmacokinetic properties in healthy human volunteers16. Because the compound was able to dramatically reduce parasite numbers in patients with P. vivax and P. falciparum patients in a single agent trial17 it has now progressed to phase IIb clinical trials (NCT03167242) where it is being tested in combination with lumefantrine. It also has impressive prophylactic activity: treating mice with a single 10 mg/kg oral dose fully protects them from mosquito-borne malaria infection. Furthermore, IZPs have gametocytocidal activity and including them in a blood meal or pretreating with IZPs prevents parasites from being transmissible to mosquitoes11, both in vitro and in vivo. If licensed, IZPs have the potential to be as significantly impactful on combating malaria as current gold standard treatments, such as artemisinin-based combination therapies. With its high potency and capacity to prevent and treat malaria as well as inhibit transmission, KAF156 could serve as an important tool in the mission to eliminate this disease.

Previous studies using in vitro evolution and whole-genome analysis in P. falciparum parasites showed that resistance to IZPs is mediated by mutations in three different genes including pfcarl, the cyclic amine resistance transporter (PF3D7_0321900);11,12 pfact, the Acetyl-CoA transporter (PF3D7_1036800); and pfugt, the UDP-galactose transporter (PF3D7_1113300)18. GFP-tagging and localization experiments have shown that these three transmembrane transporters are all localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/Golgi apparatus in Plasmodium. Multiple resistance-conferring alleles have been recovered independently in pfact and pfcarl.

It is unlikely that the nonessential pfact encodes the target, although in human cells the pfact ortholog, AT-1, appears essential18 :parasite mutants with stop codons as well as frameshifts are readily recovered after KAF156 treatment, although it is possible that mutations in pfact may confer a growth disadvantage to the parasite19. Like the parasite protein, the human protein is also localized to the ER where it serves to import Acetyl-CoA for use in lysine acetylation of some newly synthesized protein. Its disruption in human cells results in a proteasome-independent endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD)(II) mechanism involving the unfolded protein response and autophagy of the ER18. In humans, mutating lysines for some proteins such as BACE results in proteins that are retained in aggregates in the ER. Many Plasmodium proteins are acetylated20, often at conserved residues, although it is not clear that this happens in the ER and which acetyl transferases are responsible.

Pfugt encodes a member of the Solute Carrier 35 Family. Members of this family play a role in import of sugars to the ER/Golgi where most glycoconjugate synthesis occurs21. Disruption of some orthologs in worms and plants also lead to ER stress22,23. Disruption mutants in pfugt have not been obtained in high-throughput approaches in P. falciparum indicating essentiality, however, the small size of the gene and certain sequence features could contribute to the intractability of pfugt to mutagenesis screens19. Although PfCARL appears essential19, mutations in pfcarl confer resistance to unrelated compounds24,25 and resistance-conferring mutations in pfcarl are located in transmembrane regions and not in an obvious catalytic site. PfCARL, although conserved in evolution, remains understudied, but its yeast ortholog, Emp65 (Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane Protein 65) protects folding polypeptides from promiscuous degradation26. Mutations in all three parasite proteins may lead to slower rates of protein folding, processing, and sorting.

Parasites treated with IZPs have also been subjected to metabolic profiling along with other clinical compounds with known modes of action. Allman et al.27 measured changes in 113 metabolites after treatment with KAF156. These data did not show a clear metabolic perturbation, in contrast to inhibitors of cytochrome bc1, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, PfATP4, or dihydrofolate reductase, many of which are also active in both blood and hepatic stages.

Given the clinical potential of GNF179, determining its mechanism of action could reveal important new druggable pathways, suggest synergistic drugs that could be used in combination therapies, and provide clues on possible toxicity. Here we report on a series of experiments in P. falciparum and S. cerevisiae to discern the mode of action of this important antimalarial compound series.

Results

Identification of potential GNF179 targets in S. cerevisiae

For target identification, we first used in vitro evolution studies in the model system Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a strategy that has been used to discover the target of cladosporin, a tRNA synthetase inhibitor that acts against both P. falciparum and S. cerevisiae. We have recently demonstrated that yeast can be successfully used for drug target identification in both antimalarial and antitrypanosomal compounds28–30, so we decided to perform selections with GNF179. IZPs are moderately active (45 μM) against an attenuated strain of Saccharomyces that has been genetically modified by replacing 16 ABC multi-drug transporter genes with modified Aequorea victoria GFP (eGFP) and that has been dubbed the “Green Monster”31. Altogether, 13 different, independent IZP-resistant yeast lines were created by growing the cells for a minimum of 20 generations in the presence of increasing GNF179 concentrations until resistance was observed (with a minimum 1.5x IC50 increase for GNF179) (Table 1). Clonal lines were isolated from each resistant culture and retested for sensitivity. The observed resistant strains exhibited 1.5–3.1-fold resistance relative to the drug-naïve Green Monster strain.

Table 1.

Mutations identified in more than one GNF179-resistant S. cerevisiae line, from a pool of 13 evolved strains.

| Standard and systematic gene name | Strain/clone name | Amino acid change | GNF179 IC50 (µM) | GNF179-fold resistance (FR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | ABC16-Monster-Parent | N/A | 45.39 ± 5.7 | N/A |

| ELO2 (YCR034W) Fatty acid elongase, involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis | GNF179-R9-2 | G183C | 81.18 + 6.3 | 1.8 |

| GNF179-R10-2 | G183C | 90.31 ± 14.8 | 2.0 | |

| GNF179-R18g1 | L193W | 137.66 ± 5.1 | 3.0 | |

| GNF179-R8h2 | L169R | 138.05a | 3.0 | |

| GNF179-R9f2 | A186D | 94.7 ± 41.3 | 2.1 | |

| SUR2 (YDR297W) Sphingosine C4-hydroxylase | GNF179-R18g1 | S94* | 137.66 ± 5.1 | 3.0 |

| GNF179-R19g2 | D257Y | 109.35 ± 23.1 | 2.4 | |

| GNF179-R9f2 | I108K | 94.7 ± 41.3 | 2.1 | |

| ATG15(YCR068W) Phospholipase | GNF179-R18g1 | W200* | 137.66 ± 5.1 | 3.0 |

| GNF179-R19g2 | C271Y | 109.35 ± 23.1 | 2.4 | |

| GNF179-R9f2 | W380* | 94.7 ± 41.3 | 2.1 | |

| GNF179-R8h2 | K303fs | 138.05a | 3.0 | |

| LCB4 (YOR171C) Sphingoid long-chain base kinase | GNF179-R9f2 | Y421N/A423S | 94.7 ± 41.3 | 2.1 |

| GNF179-R8h2 | T336K | 138.05a | 3.0 | |

| YMR102C Protein of unknown function | GNF179-R19g2 | S448W | 109.35 ± 23.1 | 2.4 |

| GNF179-R9f2 | F381V | 94.7 ± 41.3 | 2.1 | |

| GNF179-R18g1 | L271fs | 137.66 ± 5.1 | 3.0 | |

| GNF179-R8h2 | Q98fs | 138.05a | 3.0 | |

| SEC66 (YBR171W) | GNF179-R1-2 | S107* | 80.12 ± 14.6 | 1.8 |

| Non-essential subunit of Sec63 complex | GNF179-R12-2 | M1I | 67.22 ± 10.4 | 1.5 |

Eighteen hours IC50s against GNF179 (mean ± standard error with n ≥ 2) and fold resistances (calculated relative to the parental ABC16-Monster-Parent strain) are indicated. The complete set of coding changes for the 13 resistant lines are given in Supplementary Data 1.

aReplicate not available.

We sequenced drug-resistant genomes to an average 47.3x coverage and compared these to the drug-sensitive parent (Supplementary Table 1). Excluding mutations in repetitive elements, we detected 67 total variants including 49 missense, frameshift or nonsense variants, 2 synonymous variants, 2 inframe deletions and 14 intergenics (Supplementary Data 1). The high proportion of coding to silent mutations suggests that most changes have a beneficial effect. Multiple independent alleles were found in six different genes arising in independent selections (sec66(2 variants), elo2(5), lcb4(3), YMR102C(4), atg15(4) and sur2(3)), with the most resistant lines harboring multiple mutations (e.g. GNF179-R19g2 with YMR102C, atg15 and sur2) although not generally in catalytic domains (Fig. 1a). With ~5800 genes in the genome, the probability of finding more than one allele by chance in the same gene after in vitro evolution is very low (p = 4.4e-7) and highlights the reproducibility of the selections. In addition, the set of 38 variants included singletons in the closely related genes sur1, elo3, and atg22. This mutational pattern is specific to IZPs and has not been observed for in vitro evolution with other antimalarial compounds whose targets have been identified using the Green Monster system30,32.

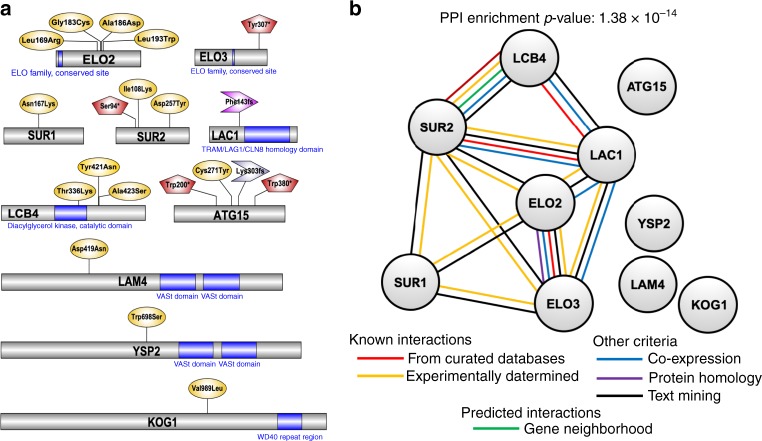

Fig. 1. GNF179-resistant yeast strains harbor mutations in endoplasmic reticulum(ER)-based lipid homeostasis and autophagy genes.

a Protein maps showing relevant mutations and PROSITE predicted protein domains, if applicable. Maps were generated using Illustrator of Biological Sequences (IBS) software package86. Missense mutations are shown in yellow ovals, nonsense mutations in red pentagons, and frameshift mutations as purple arrows. b Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was generated using the STRING database87. Each node represents a S. cerevisiae protein and connecting lines delineate interactions. The PPI enrichment p-value (p = 1.38 × 10−14) indicates that the proteins show significantly more interactions among themselves than would be expected from a random subset of genes from the yeast genome.

With the exception of YMR102C, whose function is not known, these genes are all directly or indirectly associated with trafficking and processes in the ER (Fig. 1b). SEC66 encodes a non-essential subunit of the SEC63 complex that forms a channel competent for SRP-dependent and post-translational SRP-independent protein targeting and import into the ER. SEC66 disruption is well known to slow the process of protein trafficking, such that the accumulation of differently-sized trafficking intermediates becomes evident by gel electrophoresis and immunodetection33. Similarly, ELO2 and ELO3, which encode fatty acid elongases that contribute to sphingolipid biosynthesis in the ER, were identified in a protein trafficking screen: Alleles in both ELO2 and ELO3, named VBM1 and VBM234, were identified as suppressors of a v-SNARE mutant in which yeast cells accumulate post-Golgi secretory vesicles, and are defective in invertase secretion35. ATG15 and ATG22 play a role in autophagy, which is induced in proteasome-independent ER expansion that results from aggregates of misfolded proteins. SUR1 (the catalytic subunit of mannosylinositol phosphorylceramide (MIPC) synthase that is required for biosynthesis of mature sphingolipids), SUR2 (sphingosine hydroxylase involved in sphingolipid metabolism), and LCB4 (sphingoid long-chain base kinase) are all part of the sphingolipid metabolism pathway, which is carried out in the ER. Sphingolipids and long-chain fatty acids play a role in regulating autophagy. The identification of resistance-conferring genes in S. cerevisiae whose products are localized to the ER or Golgi is similar to observations in P. falciparum, where parasite lines that have been evolved to be profoundly resistant to GNF179 also develop mutations in transporters located in the ER/Golgi complex (Supplementary Table 4).

As these resistant strains often harbored multiple mutations, we used CRISPR-Cas9 based genome editing to introduce these mutations in a drug-naïve Green Monster genetic background. For sec66 (M1I, IC50 = 70.1 ± 11.7 µM, S107*, IC50 = 74.83 ± 9.4 µM), elo2 (G183C IC50 = 88.15 ± 8.7 µM) and elo3 (Y307*, IC50 = 76.57 ± 10.0 µM) vs wild-type (WT) Green Monster IC50 = 47.3 ± 3.8 µM (Table 2), the CRISPR-edited lines exhibited similar, 1.5 to 1.9-fold levels of resistance to the drug-pressure derived lines, indicating that these three genes were responsible for the resistance observed in those yeast strains.

Table 2.

IC50s (mean and S.E.M) for GNF179 in the indicated yeast CRISPR-Cas9 edited strains.

| Strain name | Systematic gene ID | Standard gene name | Mutation | Gene description | GNF179 IC50 (µM) | GNF179-fold resistance (FR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC16-Monster | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 47.30 ± 3.8 | N/A |

| EAW361 | YBR171W | SEC66 | M1I | Non-essential subunit of Sec63 complex, involved in protein targeting and import into the ER | 70.10 ± 11.7 | 1.5 |

| EAW277 | YBR171W | SEC66 | S107* | Non-essential subunit of Sec63 complex, involved in protein targeting and import into the ER | 74.83 ± 9.4 | 1.6 |

| EAW289 | YCR034W | ELO2 | G183C | Fatty acid elongase, involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis; | 88.15 ± 8.7 | 1.9 |

| EAW327 | YLR372W | ELO3 | Y307* | Fatty acid elongase, involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis; | 76.57 ± 10.0 | 1.6 |

Strain name, systematic name, 18 h IC50s against GNF179 (mean ± standard error with n ≥ 3) and relative change compared to unedited ABC16-Monster strain are indicated.

Some of the mutations (e.g. elo2, sur2, atg15, and sec66) were early stop codons and therefore resulted in truncated proteins. To provide a further layer of confirmation for the in vitro resistance experiments, the homozygous deletion strains (which are not attenuated like the Green Monster strain)36,37 for sec66, sur2, atg15, and elo2 were tested against GNF179, revealing each to be 1.3 to 2.1-fold more resistant to IZPs (IC50 = 121.26 ± 2.9 µM (WT) vs 188.69 ± 11.4 µM (sec66Δ), 254.88 ± 55.1 µM (elo2Δ), and 217.9 ± 12.5 µM (sur2Δ) respectively). We found that the homozygous deletion strain for yer140w (which encodes the PfCARL homolog EMP6538) showed low-level resistance to IZPs (152.2 ± 10.5 µM), and a homozygous deletion of sec72, another nonessential subunit of the complex for importing proteins into the ER, also conveyed a similar level of resistance (177.37 ± 5.1 µM) (Table 3). These data suggest that modifications to either the protein export complex or lipid synthesis pathways or both can result in IZP resistance in yeast. Although the observed mutations may help overcome GNF179 treatment, it seems unlikely that these genes encode targets. Many genes are not essential and we observe stop codons. In addition, levels of resistance for isolated alleles are mild.

Table 3.

IC50s (mean and S.E.M) for GNF179 in the indicated yeast haploid deletion strains.

| Strain name | Systematic name | Mutation | Gene description | GNF179 IC50 (µM) | GNF179-fold resistance (FR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BY4742 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 121.26 ± 2.9 | N/A |

| sec66Δ | YBR171W | Haploid deletion of sec66 | Non-essential subunit of Sec63 complex, involved in protein targeting and import into the ER | 188.69 ± 11.4 | 1.6 |

| sec72Δ | YLR292C | Haploid deletion of sec72 | Non-essential subunit of Sec63 complex, involved in protein targeting and import into the ER | 177.37 ± 5.1 | 1.5 |

| elo2Δ | YCR034W | Haploid deletion of elo2 | Fatty acid elongase, involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis; | 254.88 ± 55.1 | 2.1 |

| sur2Δ | YDR297W | Haploid deletion of sur2 | Sphinganine C4-hydroxylase; catalyses the conversion of sphinganine to phytosphingosine | 217.9 ± 12.5 | 1.8 |

| emp65Δ | YER140W | Haploid deletion of emp65 | Integral membrane protein of the ER | 152.2 ± 10.5 | 1.3 |

| atg15Δ | YCR068W | Haploid deletion of atg15 | Phospholipase | 137.54 ± 12.9 | 1.1 |

Strain name, systematic name, 18 h IC50 against GNF179 (mean ± standard error with n ≥ 2) and relative change compared to wild-type are indicated. Strains obtained from yeast deletion collection36.

pfcarl mutant lines show altered sphingolipid profiles

To explore sphingolipid inhibition as a potential mechanism of action, we used a HPLC (high pressure liquid chromatography) linked to triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to measure 19 classes of sphingolipids in P. falciparum Dd2 parasites exposed to 5x IC50 (30 nM) GNF179 for 4 h. Of note, prior work has demonstrated mammalian-like sphingolipid biosynthetic activities in Plasmodium parasites39. Results with Dd2 WT parasites were compared to the pfcarl triple mutant (KAD452-R3; M81I, L830V and S1076I) that was earlier generated through in vitro evolution and is profoundly resistant to IZPs (370-fold and 340-fold resistant to KAF156 and GNF179, respectively)25. LC-MS/MS analysis of saponin-lysed parasite extracts identified dihydroceramides (DH), ceramides (C), sphingosines (So), sphinganines (Sa), and sphingomyelins (SM), with varying fatty acid chains and degree of saturation (Supplementary Fig. 1a-d).

Normalized lipidomic comparison of untreated wild-type and mutant parasites indicated that the baseline sphingolipid concentration was notably lower in the pfcarl mutant (denoted KAD). Ceramide levels (Supplementary Fig. 1b) in untreated wild-type parasites were found to be consistently higher than in the mutant, with statistical significance being observed in three out of the six identified species (C16, C20, C24). Notably, sphingomyelins (SM C18, SM C18:1) were significantly lower compared to Dd2 (Supplementary Fig. 1d). This could also be observed with sphinganine (Sa, also known as sphingosine) that showed 2-fold lower levels in the pfcarl mutant compared to its parental Dd2 line (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Lower levels were also observed for several dihydroceramides (Supplementary Fig. 1a), which can be derived from Sa via the addition of fatty acids of varying chain lengths and (de)saturation states (Supplementary Fig. 1e); As an example, C18:1 dihydroceramide was undetectable in mutant parasites. KAD and Dd2 parasites treated with GNF179, however, showed SL levels that were largely unchanged compared to untreated controls, suggesting that GNF179 does not directly inhibit SL synthesis. Further studies will be informative in assessing whether other lipid species, such as phospholipids, also show differences in their abundance in the KAD mutant line. The SL differences observed in the pfcarl mutant line are supportive of shared mechanisms of resistance to GNF179 between Plasmodium and yeast.

Localization of GNF179 within the parasite

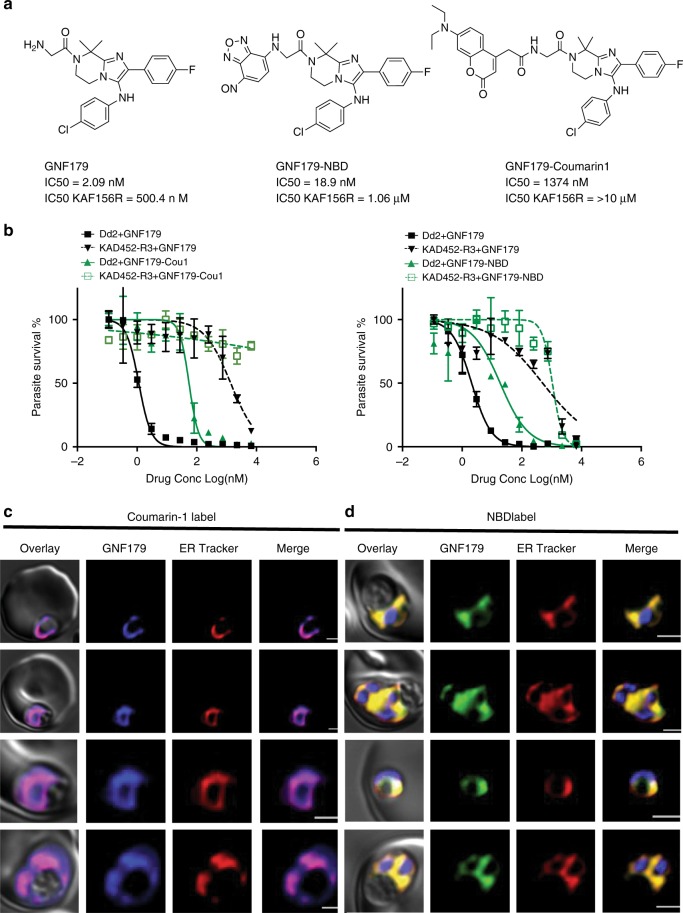

To gain further insight into the compound’s function we next examined subcellular localization using a fluorescently-conjugated form of GNF179 in P. falciparum, as recently performed for primaquine40. We first generated both NBD- or Coumarin-1-conjugated forms of GNF179 (Fig. 2a), leveraging an existing reaction series41. These modified compounds retained activity against P. falciparum blood stages, though the potency was noticeably reduced for the Coumarin-1 conjugated form of GNF179 (19 nM for NBD and 1.2 µM Coumarin-1 vs 5 nM for non-modified GNF179). However, the GNF179-resistant strain (KAD452-R3) was also resistant to the modified forms of GNF179 (Fig. 2b), indicating a similar mechanism of action for the labeled and unlabeled compounds. We first examined the localization of GNF179 in ring-stage parasites, as previous reports indicated that GNF179 is most active against early blood stages25. GNF179 colocalized with ER tracker Red, a live-cell dye that recognizes the ER42 (Fig. 2c). This, combined with the S. cerevisiae data and the localization of the three previously identified resistance genes (pfact, pfugt, and pfcarl) to the ER/Golgi, suggest that IZPs affect a process within this compartment.

Fig. 2. GNF179 localizes to the ER of early stage parasites.

a Chemical structure of canonical and NBD conjugated GNF179 and Coumarin-1 conjugated GNF179. b Dose response curves for GNF179 and Coumarin1 (left) or NBD (right) conjugated GNF179 in wild-type and KAF156-resistant clone (KAD452-R3, containing three mutations in pfcarl (M81I, L830V and S1076I). c Colocalization of Coumarin-1 conjugated GNF179 with ER-tracker red. d Colocalization of NBD conjugated GNF179 with ER-tracker red. Parasites are in mid-ring (6-hours post-infection) stage and were treated for 30 min with 2 µM GNF179-Coumarin1 and 100 nM GNF179-NBD. The blue signal represents the DAPI-stained parasite nucleus. Scale bars: 2 µm. Source data for b is provided as a Source Data file.

GNF179 inhibits protein export in P. falciparum

To further explore the hypothesis that GNF179 blocks the production or sorting of mature proteins, we next tested for synergy with known protein-export inhibitors. Brefeldin A inhibits Sec7-type GTP-exchange factors (GEFs) that catalyze the activation of a small GTPase called Arf1, responsible for ER to Golgi transport, as well as Golgi to ER retrograde transport, through the inhibition of COPI coating of secretory vesicles43, and is commonly used to inhibit protein secretion. We observed that treating parasites with sublethal concentrations of brefeldin A (1 µM) rendered parasites 5-fold more sensitive to GNF179 (IC50 of 0.8 ± 0.22 nM, vs 4.31 ± 0.88 nM without brefeldin A co-treatment) (Table 4), while sensitivity to the control drug artemisinin was unchanged. This suggests that parasites exposed to GNF179 are highly sensitive to alterations in protein export.

Table 4.

Seventy-two-hour SYBR-green IC50s for the indicated compound combinations including GNF179.

| Plasmodium falciparum drug treatment | GNF179 IC50 (nM) | Fold change in IC50 | Artemisinin IC50 (nM) | Chloroquine IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dd2 | 4.31 ± 0.88 | – | 19.4 ± 1.2 | 117 ± 14 |

| Dd2 + 1 µM Brefeldin A | 0.80 ± 0.22 | 0.19 | 21.1 ± 2.7 | 108.1 ± 17 |

| Dd2 + 5 uM Golgicidin | 1.55 ± 0.3 | 0.36 | 20.4 ± 1.9 | 108 ± 18 |

| Dd2 + 250 nM KDU691 | 1.8 ± 0.35 | 0.42 | 18.0 ± 2.4 | 90.3 ± 6 |

| Dd2 + 1 mM Thapsigargin | 4.42 ± 1.4 | 1.3 | 18.4 ± 0.8 | 139 ± 9.8 |

| Dd2 + 1 nM Carmaphycin B | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 0.75 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 90 ± 5.8 |

| Dd2 + 100 nM Cycloheximide | 2.6 ± 0.63 | 0.75 | 17.5 ± 1.52 | 101 ± 13.1 |

Parasites were synchronized to ring stage before IC50s were measured using the SYBR green method. IC50s presented as Mean ± Standard error with ≥2 biological replicates of two technical replicates each.

A similar effect was observed for two other compounds: golgicidin, another inhibitor of protein export that works through inhibition of Golgi function44, and KDU691, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type III beta (PI4KIIIβ)45. Simultaneous treatment with 5 µM golgicidin (IC50 11 µM) as well as with KDU691 (IC50 100 nM) also rendered parasites 2 to 3-fold more sensitive to GNF179 (Table 4). Interestingly, PI4K—the target of KDU691—is responsible for catalyzing the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol to generate phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P), which is found to be localized in the Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane of the parasite46. Essential for the functional and structural maintenance of the Golgi complex, dysregulation of PI4K—and subsequently PI4P—results in fragmentation of the complex as well as perturbation of transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane47.

Importantly, this observation was specific to GNF179, rather than merely a sign of generalized parasite growth impairment, as artemisinin, atovaquone and chloroquine all showed no synergy with any of these three compounds. This synergistic effect was exclusive to inhibitors of protein secretion from the ER and Golgi, as simultaneous treatment with thapsigargin, which inhibits PfATP6 and causes depletion of ER calcium levels leading to downstream inhibition of ER chaperones48, caused no change in GNF179 potency.

In addition, we tested for synergy between GNF179 and inhibitors of the P. falciparum proteasome (Table 4), to determine whether the identified increase in ubiquitinated proteins was directly involved with the efficacy of GNF179 or rather was a downstream consequence. We did not observe any synergy between GNF179 and carmaphycin B, a natural product-derived proteasome inhibitor32. This is in contrast to artemisinin, which increases the potency of carmaphycin B. This indicated to us that the increase in protein ubiquitination was a secondary effect of GNF179 inhibiting protein trafficking, rather than a direct cause.

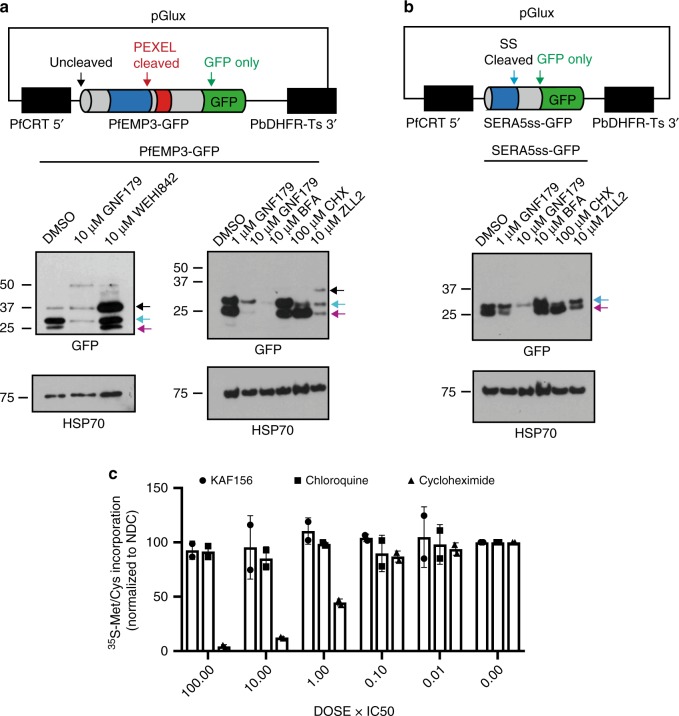

To more closely examine whether protein secretion was being blocked, we sequentially looked at protein processing in P. falciparum. In free-living organisms, proteins are trafficked to membranes or to the extracellular environment. In intracellular malaria parasites, however, proteins can be further exported into the infected red blood cell (RBC) or hepatocyte via the PTEX complex, a parasite-specific secretory complex located in the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) membrane49. To examine these two processes, we used two different transiently-expressed reporters. The first reporter (Fig. 3a) is based on a PfEMP3-GFP fusion protein and includes the first 82 amino acids of PfEMP3 (PF3D7_0201900) fused to GFP. pfemp3 encodes P. falciparum Erythrocyte Membrane 3, a protein that is exported to the surface of the infected RBC and that is needed to form knobs that permit cellular adhesion to vascular endothelial cell surface receptors. These 82 amino acids of PfEMP3 include both the signal peptide and PEXEL motif, a five-amino acid sequence (RxLxE/Q/D) present in most Plasmodium proteins exported to the RBC cytosol. This sequence is cleaved by Plasmepsin V, a type I integral membrane-bound protease with the active domain located on the luminal side of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)50. Based on where the export pathway is blocked, three different potential protein products may be observed: the full-length fusion protein, the PEXEL-domain cleaved protein, and the mature GFP degradation product after it has been exported to the RBC. As a control, we used WEHI-842, a peptide mimetic Plasmepsin V inhibitor (EC50 = 400 nM)50. Additionally, we also exposed the reporter lines to brefeldin A, cycloheximide, and an inhibitor of Signal Peptide Peptidase (SPP) ZLL251. Treatment with WEHI-842 showed a marked accumulation of the full length, unprocessed protein relative to the untreated control, as expected, given the role of Plasmepsin V in cleavage of PEXEL signal sequences. Interestingly, we also observed the full-length protein after ZLL2 treatment, suggesting that SPP is also required for the clearance of Plasmepsin V cleaved signal peptides as well as signal-peptidase-cleaved signal peptides. Parasites treated with high doses of GNF179, on the other hand, showed a marked dose-dependent decrease in levels of all forms of the secreted reporter construct (Fig. 3a). Strikingly, the western blot profile of brefeldin A- and cycloheximide-treated parasites were also different from that of GNF179 treatment. Brefeldin A treatment resulted in an accumulation of the PEXEL-domain cleaved protein and a decrease in the GFP-only species, indicating that while there is no obstruction in PEXEL cleavage, there appears to be a block in actual export to the host cell. On the other hand, treatment with cycloheximide resulted in a decrease in signal of unprocessed and PEXEL-cleaved species indicating an arrest in the synthesis of new reporter proteins—hence the only signal that remains is that of the GFP degradation products corresponding to the reporter proteins already exported prior to treatment. In contrast, levels of HSP70 protein, which does not have a signal sequence, were unchanged after treatment with GNF179, WEHI-842, brefeldin A, cycloheximide or ZLL2. This finding suggests that proteins trafficked through the ER, but not cytoplasmic proteins, are being degraded or potentially not being synthesized due to exposure to GNF179.

Fig. 3. Secretion reporter constructs demonstrate that GNF179 inhibits protein export of Plasmodium falciparum.

a Protein expression levels of PfEMP3-GFP reporter. This fusion includes the signal peptide and PEXEL motif of PfEMP3. By immunoblot, three protein products are seen with anti-GFP antibodies. The three indicated bands, in response to probing with GFP, as follows: 1. Full length protein (black arrow), 2. PEXEL cleaved protein (blue arrow), 3. GFP degradation product (magenta arrow). HSP70 is used as a loading control. b SERA5ss-GFP fusion reporter treated with GNF179. By immunoblot with anti-GFP antibodies we see two protein products for this construct: 1. Signal peptide cleaved (blue arrow) and 2. GFP degradation product (magenta arrow). HSP70 serves as a loading control. c 35S incorporation of newly synthesized amino acids at different concentrations of KAF156, chloroquine (negative control for inhibition) and cycloheximide (positive control for inhibition). Counts were normalized to data obtained from no-drug controls (NDC) and presented as mean ± SD (n = 2 independent experiments). Source data for c is provided as a Source Data file.

The second reporter construct was a SERA5ss-GFP fusion, containing the signal peptide of SERA5 (PF3D7_0207600) fused to GFP52 (Fig. 3b). SERA5 is an exported serine protease that plays a role in parasite egress from the infected RBC53. This fusion protein is co-translationally inserted to the ER and the signal peptide is removed by signal peptidase, leading to trafficking of the mature protein to the PV53. SERA5ss-GFP is therefore used as a marker of protein secretion to the PV, versus the infected RBC. The parasites were also treated with SPP inhibitor ZLL2, in addition to brefeldin A and cycloheximide. Without treatment, we also observed two protein products for this chimera corresponding to the signal sequence-cleaved species as well as the GFP only degradation product. Because the SERA5ss-GFP reporter is co-translationally processed, we are unable to see the uncleaved species of the protein. After exposure to GNF179, the reporter showed a dose-dependent reduction in overall abundance relative to the HSP70 control, as was observed for PfEMP3 reporter above (Fig. 3b). Also similar to our previous findings, brefeldin A treatment produced an accumulation of the signal sequence-cleaved species and a decrease in the GFP only species indicating an export block, while in the cycloheximide-treated cells, the strongest signal can be attributed to the GFP only degradation product. Treatment with ZLL2, in turn, resulted in a slight decrease in signal from all reporter species possibly due to the impairment of SPP-mediated clearance of signal peptidase-cleaved products in the ER membrane.

Based on results with these two reporter systems, we speculated that there was an impairment of protein secretion that occurs before signal peptide cleavage, leading to degradation of the uncleaved products or potentially a block in synthesis. Although this could be a result of reduced total protein synthesis, we observed continued incorporation of 35S methionine after treatment with GNF179, in contrast with cycloheximide (Fig. 3c). Thus, if protein synthesis was inhibited, it was likely to be restricted to a subset of proteins. To test whether the loss of reporter signal via western blot could be due to enhanced proteolysis through the ubiquitin system we compared the effects of MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, on cleaved and uncleaved reporter levels both in the presence and absence of GNF179. These data showed that proteasome inhibition, in contrast to GNF179 inhibition, did not affect the levels or processing of either the PfEMP3 or the SERA5ss reporter and that there was no observed synergy with GNF179 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We also observed that—as with MG132 treatment—there was a slight increase in ubiquitination levels after GNF179 treatment, in addition to altered banding patterns suggesting that different classes of proteins could be ubiquitinated after treatment with the two compounds.

To evaluate whether or not GNF179 triggers a significant downstream phosphorylation of eIF2α, we also probed GNF179-treated trophozoites with an antibody against the phosphorylated form of eIF2α (anti-eIF2α-p). As controls, parasites were also treated with dithiothreitol (DTT)—a known inducer of ER stress, chloroquine—which does not induce ER stress, as well as brefeldin A. Here, we found that GNF179 treatment induced a modest increase in eIF2α phosphorylation, similar to levels observed with brefeldin A, though not as pronounced as what is observed with DTT treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Our findings suggest that GNF179 is able to induce a mild ER stress response in the parasite.

We also tested whether native parasite proteins that are normally exported to the surrounding infected RBC would be retained within the parasite after exposure to GNF179. We therefore examined the intracellular levels of three PEXEL-containing proteins: PTP2 (PF3D7_0731100), PIESP2 (PF3D7_0501200), and SERA5 (PF3D7_0207600). In all three cases, after a short, 3-hour exposure with 10 µM GNF179 (same conditions as above for the reporters for both GNF179 and WEHI-842), we observed a modest accumulation of all three proteins suggesting impairment of protein export from the parasite (Supplementary Fig. 3). A conditional knockdown of PfSEC62 using the glmS ribozyme system54,55 showed that parasites were 3-fold more sensitive to GNF179 (0.66 nM for 3D7 wildtype vs 0.24 nM for PfSEC62 kd) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

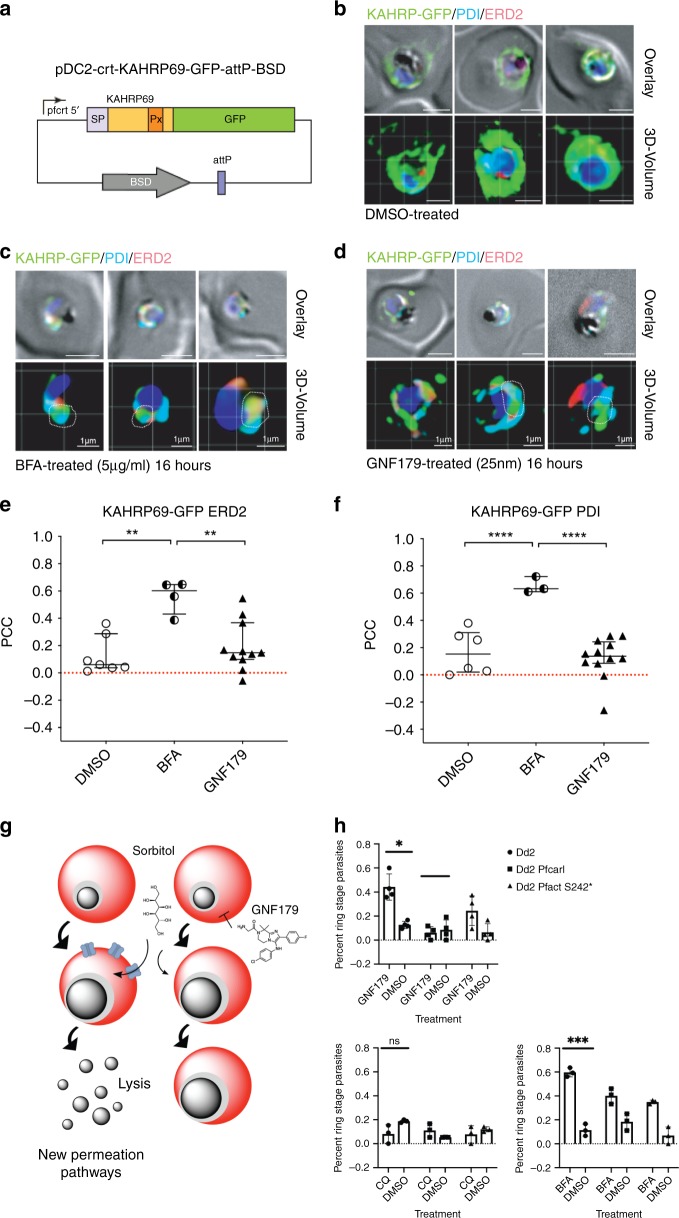

Finally, we validated the effect of GNF179 on parasite protein export in live parasites through two parallel strategies, using brefeldin A as a positive control: visualization of export of fluorescent reporter proteins, and examination of functional phenotypes that would result from inhibition of protein secretion. To begin, we constructed a parasite strain that bears a fusion between the Knob-Associated Histidine Rich Protein and GFP56 (Fig. 4a). The chimeric gene, which consists of the first 69 amino acids of KAHRP containing the signal peptide (SP) and PEXEL motif (Px), was expressed from a pfcrt promoter and was integrated into the cg6 locus in Dd2-attB parasites using the attP × attB integrase system57. To better understand in which subcellular compartment the export block occurred we co-stained with antibodies to both the cis-Golgi resident protein, ERD258, and to the ER (PDI). In the absence of GNF179 the GFP reporter was trafficked to the PV as well as to the RBC cytosol, as shown by the GFP staining in and outside the PV surrounding the parasite (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 5a). In contrast, treatment with brefeldin A resulted in accumulation of the GFP reporter in the parasite ER as evidenced when co-staining with an anti-PDI antibody (cyan) (Fig. 4c, f) or by using ER tracker (red) (Supplementary Fig. 5c, f). The white dotted outlines indicate overlap of green and cyan labels. We also observed some colocalization between the GFP and ERD2 signal (Fig. 4c, e) under brefeldin A treatment, though this correlation is lower than what is seen between GFP and PDI. Interestingly, treatment with 5x IC50 GNF179 (25 nM) for 16 hours did not show significant colocalization of the GFP signal with either organelle specifically (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5). While the images clearly demonstrate inhibition of KAHRP-GFP export, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the GFP-ERD2 (Fig. 4e), GFP-PDI (Fig. 4f), and GFP-ER tracker (Supplementary Fig. 5f) signals indicate that the GFP signal is not significantly overlapping with either marker though it appears to be closely associated with the ER. Additionally, staining of parasites with ER-tracker after GNF179 treatment showed an expansion of the ER tracker positive space relative to nuclear staining (Supplementary Fig. 5d). 3D volume quantification of the ratio between DAPI-positive staining to ER-staining in live, GNF179-treated parasites showed a statistically-significant expansion of the ER (Supplementary Fig. 5e). We speculate that the signal is being sequestered in intermediate compartments that are highly associated with the ER-Golgi complex. Two candidates in particular, come to mind: ERGIC, the ER-Golgi Intermediate Compartment, a known system of membrane clusters where anterograde and retrograde transport take place59; or the newly identified TIGER domain, a subcellular compartment that is intertwined with the ER and is thought to be responsible for enabling the formation of specific protein interactions in newly translated membrane proteins60.

Fig. 4. Confirmation of GNF179’s inhibition of protein export in P. falciparum blood stage parasites.

a Vector used for assays shown in b–d. b–d Imaging of GFP reporter to the plasma membrane under the indicated compound treatments for 16 h. Parasites were fixed and stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue), α-GFP (green), α-ERD2 (red) and α-PDI (cyan) antibodies. Scale bars: 2 µm unless otherwise indicated. Overlay: DIC images merged with fluorescent channels. Quantification of colocalization between KAHRP-GFP and ERD2 (e), and between KAHRP-GFP and PDI (f) are indicated by Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC); Each dot represents an individual parasitized red blood cell. Statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test where where * is p < 0.05, ** is p < 0.01, *** is p < 0.001, and **** is p < 0.0001. g Model for establishing new permeation pathways. If proteins are not exported to the red cell where they can form new permeation pathways, sorbitol will not be imported and cause lysis. h Percentage of rings (mean ± SEM, at least three independent experiments) from an asynchronous parasite population 24 h after sorbitol synchronization, treated as indicated by GNF179 (5 nM), Chloroquine (CQ, 500 nM) or brefeldin A (BFA, 5 µM). Statistical significance was determined using a paired, two-tailed t-test where * is p < 0.05, ** is p < 0.01, and *** is p < 0.001. Dd2 pfcarl experiments were conducted with the pfcarl evolved triple mutant (KAD452-R3) and edited Dd2-ACTStop mutant. For sensitive parasites (Dd2), 25 nM of GNF179 was used, while 1 µM was used on resistant parasites. Source data for e, f, and h are provided as a Source Data file.

To functionally confirm a secretion defect, we next determined whether parasites treated with GNF179 would be less sensitive to sorbitol treatment, which kills mature parasites and is used to synchronize cultures as only ring-stage parasites survive. For sorbitol to kill later stage parasites, the new permeability pathways (NPPs) must first be established in the RBC, which requires the export of a network of transport proteins61 (Fig. 4g). Here, we observed that 4 h of pretreatment with 25 nM GNF179 led to a loss of sensitivity to sorbitol, as seen via the presence of a nearly asynchronous culture 24 h post synchronization (Fig. 4h). This was in contrast to parasites that were GNF179-resistant, resulting from mutations in either pfcarl (KAD452-R3), or, to a lesser degree, pfact (Dd2-ACTStop) (Fig. 4h). Those resistant parasites showed less protection and more sorbitol lysis. As controls we observed a similar phenotype with brefeldin A but not with chloroquine. The lack of sorbitol sensitivity in the presence of GNF179 further highlights the impairment of ER-mediated protein trafficking due to GNF179 exposure.

Discussion

Once the parasite has successfully invaded the host cell, the parasite undergoes a rapid induction of protein synthesis62. This includes the folding and sorting of hundreds of membrane proteins and the secretion of hundreds of proteins into the host cell via the parasite ER and the PTEX complex in the PVM, leading to a dramatic rearrangement of host cell processes, all essential for parasite survival. Proteins needed for these essential processes may make effective drug targets, as shown by the development of WEHI-842, an inhibitor of Plasmepsin V63. In addition, KDU691 targets PI4K45, a protein involved in a variety of processes including vesicular trafficking from the Golgi apparatus. While the trafficking of proteins into the infected RBC may only occur during the asexual blood stage, general trafficking and protein modification is a process that occurs, at least to some degree, at all stages of parasite development. Therefore, proteins that play a role in protein processing or sorting pathways would be logical targets for the type of multistage (hepatic, asexual blood, and gametocyte stages) activity possessed by IZPs.

The ER serves as the initial entry into the protein trafficking and secretion pathways, as a site for protein folding, and as the location of a significant portion of the post-translation modification of parasite proteins. All of our available data suggest that IZPs exerts their effect in this organelle, including the localization of gene products that give resistance (in both S. cerevisiae and P. falciparum) to KAF156/GNF179 as well as the localization of NBD and Coumarin-labeled compounds. The ER is responsible for many functions, including lysine acetylation, protein folding, glycosylation and sphingolipid biosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. 6). After proteins have been modified and folded, they are sorted to other compartments. While KAF156/GNF179 may block the sorting of proteins to other compartments, our data seem more compatible with these compounds working at an earlier stage of protein production, possibly during protein folding. Western blot analysis shows a substantial reduction in the total amounts of secreted reporter proteins relative to cytoplasmic proteins after GNF179 treatment, suggesting that the synthesis of both membrane and PTEX-trafficked proteins may be disrupted. The reduction in protein levels is in contrast to using the WEHI-842 inhibitor of the ER-based Plasmepsin V export protease, where a shift from the processed to the unprocessed form of the protein is observed yet protein reporter levels stay high. Levels of proteins that are not exported to the RBC but have a simple signal sequence are also reduced (Fig. 3).

While a block in the synthesis of membrane proteins might be expected to result in an unfolded protein response and synergy with proteasome inhibitors such as carmaphycin B, there are different degradation pathways for cytoplasmic proteins versus proteins that are destined to be secreted. Recent data reveal the existence of two pathways for dealing with protein aggregates in the ER: ERAD(I) and ERAD(II)64. While ERAD(I) is driven by the ubiquitylation-dependent proteasomal degradation of target proteins, ERAD(II) depends on autophagy and lysosomal trafficking for the disposal of large protein aggregates, and is observed in human cells when Acetyl-CoA Transporter is disrupted65. It is likely that ERAD(II) is used when secreted reporters (e.g. KAHRP69-GFP) are overexpressed, as we observed no great increase in ubiquitinated proteins after GNF179 treatment except when a proteasome inhibitor (MG132) was used in combination with GNF179 (Fig. S2). An expansion of the ER, similar to that observed after GNF179 treatment in malaria parasites (Fig. S5), is observed when yeast cells are treated with agents that induce the unfolded protein response. ER expansion induces autophagy as a mechanism to deal with ER-stress and eliminate the blockage66.

Although GNF179 appears to work in the ER, its exact target remains unknown. The cancer and antinfectives drug discovery communities have explored this organelle and its processes as targets (reviewed in ref. 67); notably, the ER protein-folding factory examined here also contains targets for antivirals as viruses need to be packaged within the ER67. In addition, it has been established that the P. falciparum Signal Peptide Peptidase PfSPP1 is a drug-able target and its inhibition results in parasite death across the lifecycle68. Conservation of critical targets across species seems to be more the rule than the exception although selectivity of inhibitors may be very different.

Although it is difficult to predict a target based on chemical structure, KAF156/GNF179 has structural features that suggest it may inhibit a kinase or other ATP or GTP binding proteins. Many potential essential targets with ATP or GTP binding pockets are present in the ER-dependent protein packaging pathway. Members of the Sec62 translocon complex could be possible targets. However, Sec62 does not have an obvious catalytic site, a feature that is associated with many targets, although it is possible that IZPs are allosteric inhibitors. Signal recognition particle (SRP) is a protein complex critical for the translocation of proteins into the ER69. Within this complex, both SRP54 and SRPα harbor GTPase domains, both of which would represent prime drug-able targets. However, these data would not explain the increased ER volume that is observed with GNF179-exposed parasites. Other candidates may include heatshock proteins such as the GRP94-like protein endoplasmin (PF3D7_1222300). This essential protein has an ATP-binding domain and selective targeting with small molecule inhibitors is possible70. GRP94 homologs are not found in yeast and bacteria. However, GRP94 is functionally similar to HSP82. In fact, in our yeast selections we detect a Ser to Ile substitution at position 17 that lies in proximity to the ATP-binding pocket. However, the lack of a close ortholog may explain the 10,000-fold difference in potency in the yeast model. In addition, binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP), the Hsp70 homologue within the ER (PF3D7_0917900), requires ATPase activity to perform the final step of protein translocation from the SEC61 translocon into the ER71 and could also be a plausible target. Chemical targeting of BiP is feasible72. The hypothesis that KAF156/GNF179 targets protein folding in the ER is supported by the role of EMP65 as a guardian factor that protects newly synthesized, unfolded polypeptides from degradation (See Supplementary Fig. 6 for model). If pfcarl-emp65 is mutated, more premature degradation may occur in the presence of GNF179/KAF156, which may allow the cells to tolerate 10X more GNF179.

Another potential class of proteins are Rab GTPases. Given the synergy we observed between GNF179 and brefeldin A, GNF179 could inhibit COPI-mediated transport from the ER to the Golgi, similar to the mechanism of action of brefeldin A73. Sar1, an essential gene involved in the Sec23 complex, for example, is a small GTPase that functions as a target in a yeast brefeldin suppressor screen73. The lysine transferase that adds acetyl groups to nascent peptides, helping them fold and which relies on PfACT activity could be a target.

Protein glycosylation in the ER may could also be inhibited and may lead to unfolded aggregates within the ER. Tunicamycin, a nucleoside analog, inhibits protein N-linked glycosylation by preventing core oligosaccharide addition to nascent polypeptides by binding to UDP-N-acetylglucosamine--dolichyl-phosphate N-acetylglucosamine phosphotransferase (Alg7). Tunicamycin thereby also blocks protein folding and transit through the ER. The P. falciparum version of Alg7, PF3D7_0321200, could theoretically be a target, although the structure of KAF156 is not similar to tunicamycin.

It is also worthwhile to note that several additional compounds may work via similar or related mechanisms. For example, mutations in pfcarl are acquired when parasites are treated with sublethal concentrations of MMV00756425. In particular, if there is a pfcarl or pfact resistance mechanism, it seems likely that protein folding or trafficking in the ER is targeted. More work will be needed to determine whether MMV007564 has the same target as KAF156 or if they only act against the same pathway. By comparison, there are a variety of different chemotypes that inhibit mitochondrial function74, as well as different chemotypes that interact with the same active site, however, there still seem to be a limited number of high-value inhibitor binding sites in this pathway, and they appear repeatedly.

An additional mechanism of action for IZPs could be inhibiting the process of ER autophagy. The mammalian orthologue of Sec62, potentially a target of GNF179, is required for the degradation of excess ER components in a process termed ER autophagy75. In vitro directed evolution of S. cerevisiae using GNF179 identified mutations in the atg15 and atg22, genes that play a role in ER-autophagy. In addition, GNF179 induced an expansion in ER size upon treatment of P. falciparum. Collectively, these results suggest that IZPs affect ER homeostasis and function by inhibiting proteins critical for ER-phagy.

Strategies for finding the target of KAF156 remain limited in the absence of genetic methods, and few antimalarials have been matched with their target when genetic methods fail. Affinity-based methods were used to match MMV030048 to PI4K with success76, although such strategies required the use of a modified ligand. Cellular Thermal Shift Assays (CETSA) methods that involve incubating total cellular extracts with an unmodified ligand and identifying those proteins that resist heat denaturation in the presence of compound is a strategy that shows promise77. Another potential option involves a genome-wide knockdown or knock-in libraries, which have been used with success in trypanosomes and to find the target of cladosporin also using the S. cerevisiae model78. A limitation of all of these genome-wide methods is that they may produce hundreds of possible candidate molecules, and it can be challenging to sort through them using the slow methods available in Plasmodium. While finding the exact target may require further work, the studies here should allow prioritization of candidates that are identified in genome-wide experiments.

Methods

Resistance evolution of GNF179-resistant S. cerevisiae

Sublethal concentrations of GNF179 were added to 50 ml conical tubes containing 20 µl of saturated S. cerevisiae ABC16-Monster cells in 20 ml of YPD media. Each selection was cultured under vigorous shaking until the culture reached saturation. Saturated cultures were diluted into fresh YPD media containing increasing GNF179 concentrations, and multiple rounds of selection were performed. Cells of cultures that were able to grow in substantially higher drug concentrations than the parental cell line, were streaked onto agar plates containing GNF179 to select for single colonies. Single colonies were isolated, and IC50 assays, prepared by two-fold dilution were performed to determine the degree of evolved resistance vs. that of the parental strain.

Whole-genome sequencing of GNF179-resistant S. cerevisiae

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from yeast samples using the YeaStar Genomic DNA kit (Cat. No D2002, ZYMO Research). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina Nextera XT kit (Cat. No FC-131-1024, Illumina) following the standard dual indexing protocol, and were then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 in RapidRun mode to generate paired-end reads 100 bp in length. Reads were aligned to the S. cerevisiae 288 C reference genome (assembly R64) using BWA-mem79 and further processed using Picard Tools (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). A total of 13 clones were sequenced to an average coverage of 47.3×, with an average of 99.3% of reads mapping to the reference genome. SNVs and INDELs were called using GATK HaplotypeCaller, filtered based on GATK recommendations80 and annotated with SnpEff81. Variants were further filtered by removing mutations that were present in the both drug-sensitive parent strain and resistant strains, such that mutations were only retained if they arose during the drug selection process. Evolved yeast strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

CRISPR-Cas9 allelic exchange in S. cerevisiae

CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering was performed on the S. cerevisiae ABC16-Monster strain using vectors p414 and p426 obtained from the Church lab (Addgene) as previously described29. To produce gRNA plasmids specific to the desired mutation sites, oligonucleotides were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) to match the target sequence and contain a 24 base-pair overlap with the p426 vector backbone. Gene-specific gRNAs were amplified by PCR, transformed into StellarTM competent E. coli cells (Takara) and selected on LB-Ampicillin plates. DNA was isolated from transformed E. coli cells and purified using the QiaQuick Miniprep kit (Qiagen) and quantified via Qubit Fluorometric Quantitation (ThermoFisher). Cas9-expressing ABC16-Monster cells were transformed with 300–500 ng of gene-specific gRNA vector and 1–2 nmole of synthesized donor template (IDT) containing the desired base-pair substitution via standard lithium acetate method. Transformed cells were selected on methionine and leucine deficient CM-glucose plates. Each mutation was confirmed with Sanger sequencing (Eton Bioscience). Sequences of primers and oligonucleotides used for this study can be found in Supplementary Table 3. Edited yeast strains generated for this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

P. falciparum culture

P. falciparum Dd2 strain parasites were cultured under standard conditions82, using RPMI media (Thermo Fisher # 21870076) supplemented with 0.05 mg/ml gentamycin (Thermo Fisher # 15710072), freshly-prepared 0.014 mg/ml hypoxanthine (Sigma Aldrich #H9377), 38.4 mM HEPES (Sigma Aldrich #H3375), 0.2% Sodium Bicarbonate (Sigma Aldrich #S5761), 3.4 mM Sodium Hydroxide (Sigma Aldrich #S8045), 0.05% O+ Human Serum (Denatured at 560C for 40 min and obtained from Interstate Blood Bank, Memphis, TN) and 0.0025% Albumax (Thermo Fisher Scientific # 11021037). Human O+ whole blood was obtained from The Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA) using the Normal Blood Program and Humann Subjects Protocol Number (IRB-12-5933). Leukocyte-free erythrocytes were stored at 50% hematocrit in RPMI-1640 screening media (as above, but without O+ human serum and with 2x albumax concentration) at 4 °C for one to three weeks before experimental use. Cultures were monitored every one to two days via direct observation of parasite infection using light microscopy-based observation of Giemsa-stained thin blood smears of parasite cultures. Specific parasite cultures used are as indicated in the specific experiments. Additionally, all parasite strains used for this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Sphingolipid quantitation

Parasites were grown in culture media containing both human serum (5%) and albumax (0.25%) at 3% hematocrit. Asynchronous parasites (containing ~2/3 rings) were treated with GNF179 for 4 h at 5X wild type IC50 (25 nM). Parasitized cells were then washed with PBS (+drug for GNF179-treated samples). Samples were then lysed with 5 volumes of 0.15% saponin (in cold PBS) on ice for 20 min, and centrifuged and washed extensively. Parasite pellets were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford Protein Assay for biological (n = 3) and technical (n = 2) replicates for WT and mutant parasites ± drug. Samples were solubilized using cell lysis buffer comprising 1 M Tris, 20% SDS, 0.5 M EDTA, β-mercaptoethanol and double distilled water then boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards and parasite samples were incubated with Bradford Reagent (BioRad) at room temperature for 15–30 min then absorbance read at 595 nm in order to derive protein concentrations.

For lipid extraction, parasite samples and controls for lipid analysis were prepared in a 96-well plate comprising a final volume of 50 μl per well. To each well, 50 μl internal standards comprising ceramide (C12) and sphingomyelin (SM12) were added. Lipids were extracted from parasite and control samples using 900 μl dichloromethane/methanol (1:1 v/v). The plate was vortexed overnight at room temperature then centrifuged to pellet out all insoluble material. The supernatant containing lipids was transferred into a new plate and samples subjected to mass spectrometry using a triple quadrupole LC-MS system. Briefly, 7 μl of sample was injected into the HPLC running through a C18 Poroshell column into Agilent QQQ 6430 MS/MS. HPLC was optimized under the following conditions: mobile phase A (water/methanol/ chloroform/0.1% formic acid) and mobile phase B (methanol/ acetonitrile/chloroform/0.1% formic acid). Analysis was done on Agilent Quantitative Analysis software and normalized to total protein in the samples. All sample data sets were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism 4.0 and sphingolipid content was compared across all possible combinations of data in treated (+) and untreated (−) wild type (Dd2) and pfcarl mutant (KAD452-R3) parasites.

Evaluating protein trafficking defects

P. falciparum parasites expressing PfEMP3-GFP or PfSERA5ss-GFP were generated as previously described in ref. 49, with the indicated reporters cloned into pGLUX.1 and their expression driven by the PfCRT promoter. P. falciparum trophozoites expressing PfEMP3-GFP or PfSERA5ss-GFP were magnetically-purified (Miltenyi Biotech), incubated with 1 µM and 10 µM GNF179, 10 μM brefeldin A, 100 μM cycloheximide, and 10 μM ZLL2 for 4 h at 37 °C, and treated with 0.09% saponin-containing inhibitor. Washed pellets were solubilized in 2x Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad #1610737) then boiled for 3 min. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and blocked in 1% skim milk. Membranes were probed with mouse anti-GFP (Roche, cat. no. 11814460001) (1:1000) (primary validation is provided on the manufacturer’s website) or rabbit anti-HSP70 (1:4000), subsequently followed by probing with species-matched horseradish peroxidase HRP–conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, cat. nos. 7074 and 7077) and visualization with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). Supplementary Fig. 7 shows uncropped GFP- and HSP70-probed blots corresponding to three independent experiments.

For endogenous proteins, 3D7 wild-type Plasmodium parasites were treated with the indicated concentrations of GNF179 for 3 h at 37 °C, and treated with 0.09% saponin-containing inhibitor. Immunoblotting was performed as described above using antibodies for PfIESP2, PfSERA5 and PfPTP283.

Evaluating Ubiquitination and eIF2α phosphorylation

To measure ubiquitin response after GNF179 treatment, P. falciparum trophozoites expressing PfEMP3-GFP or PfSERA5ss-GFP were magnetically-purified (Miltenyi Biotech), incubated with 10 µM MG132 alone, 10 µM GNF179 alone, and a combination of 10 µM MG132 and 10 µM GNF179 for 3 hours at 37 °C. The parasitized RBCs were then treated with 0.09% saponin-containing inhibitor. Washed pellets were solubilized in 2x Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad #1610737) then boiled for 3 min. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and blocked in 1% skim milk. Membranes were probed with mouse anti-Ubiquitin (PD41 Cell Signalling Technology #3936) (1:1000) or rabbit anti-HSP70 (1:4000), subsequently followed by probing with species-matched HRP–conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, cat. nos. 7074 and 7076) and visualization with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

To measure eIF2α phosphorylation after GNF179 treatment, highly synchronized, wild-type (Dd2-strain) P. falciparum early trophozoites were incubated for 90 minutes at 37 °C with 0.5 µM/5 µM Chloroquine, 0.5 µM/5 µM GNF179, 0.1 mM/1 mM brefeldin A, and 5 mM DTT. The parasitized RBCs were then lysed using 0.09% Saponin, and pellets were solubilized in 2x Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad #1610737) then boiled for 3 min. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Membranes were subsequently probed with rabbit anti-eIF2α-p (Cell Signaling Technology-119A11) (1:800) or mouse anti-HSP70 (1:2500), followed by incubation with species-matched, HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and then visualized using chemiluminescence (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Sec62 knockdown assay

3D7 wild type and PfSec62-HA-glmS transgenic parasites55 were synchronized using sorbitol at ring stage and incubated with 0 mM and 1 mM Glucosamine (Sigma). GNF179, chloroquine and mefloquine were added at increasing concentrations and all cultures incubated for 48 hrs until the late ring stage of the successive cycle. Parasitaemia at each drug concentration was assessed by flow cytometry and all data tabulated using GraphPad Prism.

Measuring parasite translation using 35S-incorporation

The effect of drug treatment on parasite translation was evaluated by quantifying the incorporation of 35S-labeled amino acids into newly synthesized protein by adapting a published protocol84. Briefly, synchronized, trophozoite-stage parasites (5% parasitemia, 26-30 hpi) were first washed in methionine-free media three times prior to drug treatment. Parasites were then incubated in various compound concentrations in 24-well plates for 1 h at 37 °C, at a final hematocrit of 5%, and a final concentration of 125 µMci/mL of EasyTag™ EXPRESS 35S Protein Labeling Mix (Perkin Elmer, USA). Concentrations used for incubation correspond to 100-, 10-, 1-, 0.1-, and 0.01-times the IC50 values of KAF156 (15 nM), chloroquine (85 nM) and cycloheximide (750 nM). After incubation, parasites were washed with 1x PBS and then lysed using ice-cold 0.15% saponin in 1x PBS for 20 min. All subsequent steps were performed on ice. The saponin pellet was washed with 1x PBS, and then resuspended in 0.02% sodium deoxycholate and supplemented with an equal volume of 16% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to make a final concentration of 8% TCA. The suspensions were then incubated for 20 min on ice before vacuum filtration. To collect the radiolabeled, precipitated proteins, the samples were dispensed onto 0.7 µM glass fiber filter discs (Millipore, USA) that had been presoaked in 8% TCA. The vacuum-filtered precipitates were then washed twice with 8% TCA and then, finally, with 90% acetone. The filter discs were allowed to air-dry for at least two hours, transferred into scintillation vials and resuspended in scintillation cocktail (Perkin Elmer, USA). 35S counts were obtained for 1 min using a Beckman Coulter LS 6500 Multi-purpose Scintillation Counter. Counts were normalized to data obtained from untreated parasites.

Assessment of new permeation pathways

Parasites were cultured as above. Three parasite strains were used, wild-type Dd2, KAD452-R3, and Dd2 ACT S242* (Dd2 act - PF3D7_1036800 – with S242* SNV24). Each parasite clone was split into three sets of matched cultures. Each set of matched cultures was either treated for 4 h at 37 °C with compound (50 nM GNF179, 500 nM Chloroquine or 5 µM brefeldin A (Sigma Aldrich #B6542)) or an equal volume of DMSO. After drug treatment, cultures were synchronized by treatment with 5% sorbitol (Sigma Aldrich # 240850) for 10 min at 37 °C, washed once with media and returned to normal culture conditions. 24 h after treatment, cultures were assessed by thin blood smear and GIEMSA staining for parasite lifecycle stage. The proportion of early (“ring”) stage parasites to the total parasite proportion was recorded.

Microscopy methods parasite culture

P. falciparum asexual blood stage parasites were cultured in human erythrocytes (3% hematocrit) and RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 mg/L hypoxanthine, 25 mM HEPES, 0.225% NaHCO3, 10 mg/L gentamycin, and 0.5% (w/v) Albumax II (Invitrogen). Parasites were maintained at 37 °C in 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2. Cultures were stained with Giemsa, monitored by blood smears fixed in methanol, and viewed by light microscopy.

Export block assay

The KAHRP69-GFP reporter line was generated by amplifying the first 207 bp of the KAHRP gene (PF3D7_0202000), which includes the signal peptide and PEXEL motif, followed by a glycine linker, and cloning upstream of GFP in the pDC2-crt-attP-BSD vector under the control of the pfcrt 5’ UTR. The plasmid was integrated by attB x attP recombinase-mediated integration into the Dd2attB parasite line85. Dd2attB KAHRP69-GFP ring stage parasites were incubated with either 5×IC50 GNF179 (25 nM), brefeldin A (5 µg/ml) (Sigma Aldrich) or DMSO-mock treated 16 h prior to imaging. For live-cell imaging, 5 µl of resuspended culture was added to 30 µl of RPMI-1640 media (without Albumax II) containing Hoechst 33342 (1 µg/ml) (Sigma) and imaged at room temperature after 5 min incubation at 37 °C. For experiments with ER-TrackerTM Red (Thermo Fisher), the dye was added to a final concentration of 1 µM 30 min prior to imaging. Indirect Immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) were performed in suspension. Cells were fixed in 4% (v/v) formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at RT followed by a second fixation step supplementing the 4% formaldehyde solution with 1 mM Cysteine and CaCl2 and subsequent incubation over night at 4 °C. The cells were permeabilized on ice using 0.05% Triton X-100 in 1x PBS for 5 min and autofluorescence was quenched using 50 mM glycine for 10 min. After two washes in 1x PBS the cells were resuspended in 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1x PBS blocking buffer and incubated with the appropriate dilution for each primary antibody used (1/200 for anti-ERD2, 1/200 for anti-PDI (Mouse anti-PDI (1D3), Enzo Life Sciences, Cat. No. ADI-SPA-891-D), 1/500 for anti-GFP) followed by an incubation with the species-specific corresponding secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488-, 594- or 647- conjugated goat anti mouse or rabbit antibodies, Thermo Fisher) diluted 1:2000 in 1% BSA in 1x PBS.

Parasites were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E wide-field microscope equipped with a sCMOS camera (Andor) and a Plan-apochromate oil immersion objective with 100× magnification (1.4 numerical aperture). A minimum of 27 Z-stacks (0.2 μm step size) were taken of each parasitized RBC. NIS-Elements imaging software (Version 5.02, Nikon) was used to control the microscope and camera as well as to deconvolve the images (using 25 iterations of the Richardson-Lucy algorithm for each image) and perform 3D reconstructions. Quantitative co-localization analysis of the deconvolved Z-stacks was performed using the GA3 pipeline (General analysis Pipeline 3; NIS-Elements software; developed in collaboration with Nikon). ImageJ (Fiji) (version 2.0.0-rc-68/1.52 h) was used to crop the images, adjust brightness and intensity, overlay channels and prepare montages.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Winzeler lab for technical support, reagents and critical reading of the manuscript. G.L. is supported by an AP Giannini post-doctoral fellowship. S.O. and G.M.G. were funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1054480, and OPP1171497). T.J.E. and R.M. were supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant No. 91516). R.M. also acknowledges the University of Cape Town for a travel grant. M.R.L. was supported in part by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Award from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (T32 GM008666). M.C.L gratefully acknowledges funding from Wellcome and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. D.A.F. gratefully acknowledges funding from the Medicines for Malaria Venture and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. E.A.W. is supported by grants from the NIH (5R01AI090141 and R01AI103058) and by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1086217and OPP1141300) as well as by Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV).

Author contributions

Parasite functional assays were conceived by G.L., F.R., D.S.M., D.A.F., A.F.C., and E.A.W. Parasite functional assays, including gene knockdowns, drug synergy experiments, conditional knockdowns, in vivo translation assays, and western blots were performed by G.L., F.R., D.S.M, J.K.T., B.Y.Z., and D.H. Lipidomics experiments were conceived by D.A.F., T.J.E., and T.S.W. and performed by T.S.W., R.M., and T.S.K. The KAHRP69-GFP line was generated by M.C.L. and immunofluorescence assays and live microscopy experiments were performed by N.F.G. S. cerevisiae resistance evolutions and functional assays were performed by E.V., J.Y., A.L.C., P.K. G.G., and S.O. Whole-genome sequencing was performed by the UCSD Institute for Genomic Medicine Core Facility and analyzed by M.R.L. utilizing the pipeline developed by R.M.W. Fluorescent compounds were synthesized by D.S, T.J., and J.H. E.A.W. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the paper.

Data availability

All genome sequences for the 13 IZP-resistant S. cerevisiae strains have been placed in the short-read sequence archive [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra] under accession code STUDY: PRJNA381796 (SRP107357). The source data underlying Figs. 2b, 3c, 4e, 4f, and 4h are provided as Source Data file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Paul Denny, Yo Suzuki and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Gregory M. LaMonte, Frances Rocamora.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-15440-4.

References

- 1.WHO. World malaria report 2018, (World Health Organization, 2018).

- 2.Snow RW, Craig M, Deichmann U, Marsh K. Estimating mortality, morbidity and disability due to malaria among Africa’s non-pregnant population. Bull. World Health Organ. 1999;77:624–640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gething PW, et al. A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010. Malar. J. 2011;10:378. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidhu ABS, Verdier-Pinard D, Fidock DA. Chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum Malaria parasites conferred by pfcrt mutations. Science. 2002;298:210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1074045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suwanarusk R, et al. Chloroquine resistant Plasmodium vivax: in vitro characterisation and association with molecular polymorphisms. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok S, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is associated with an altered temporal pattern of transcription. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White NJ. Antimalarial drug resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:1084–1092. doi: 10.1172/JCI21682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui L, Mharakurwa S, Ndiaye D, Rathod PK, Rosenthal PJ. Antimalarial drug resistance: literature review and activities and findings of the ICEMR network. Am. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 2015;93:57–68. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farooq U, Mahajan RC. Drug resistance in malaria. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2004;41:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dondorp AM, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhen KL, et al. KAF156 is an antimalarial clinical candidate with potential for use in prophylaxis, treatment, and prevention of disease transmission. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5060–5067. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02727-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meister S, et al. Imaging of Plasmodium liver stages to drive next-generation antimalarial drug discovery. Science. 2011;334:1372–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1211936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plouffe D, et al. In silico activity profiling reveals the mechanism of action of antimalarials discovered in a high-throughput screen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9059–9064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802982105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagle A, et al. Imidazolopiperazines: lead optimization of the second-generation antimalarial agents. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:4244–4273. doi: 10.1021/jm300041e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu T, et al. Imidazolopiperazines: hit to lead optimization of new antimalarial agents. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:5116–5130. doi: 10.1021/jm2003359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leong FJ, et al. A first-in-human randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single- and multiple-ascending oral dose study of novel Imidazolopiperazine KAF156 to assess its safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics in healthy adult volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:6437–6443. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03478-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White NJ, et al. Antimalarial activity of KAF156 in falciparum and vivax malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1152–1160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim, M. Y., et al. UDP-galactose and acetyl-CoA transporters as Plasmodium multidrug resistance genes. Nat. Microbiol.1, 16166 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zhang M, et al. Uncovering the essential genes of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum by saturation mutagenesis. Science. 2018;360:eaap7847. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao J, et al. Extensive lysine acetylation occurs in evolutionarily conserved metabolic pathways and parasite-specific functions during Plasmodium falciparum intraerythrocytic development. Mol. Microbiol. 2013;89:660–675. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishida N, Kawakita M. Molecular physiology and pathology of the nucleotide sugar transporter family (SLC35) Pflug. Arch. 2004;447:768–775. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reyes F, et al. AtUTr1, a UDP-glucose/UDP-galactose transporter from Arabidopsis thaliana, is located in the endoplasmic reticulum and up-regulated by the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9145–9151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dejima K, et al. The ortholog of human solute carrier family 35 member B1 (UDP-galactose transporter-related protein 1) is involved in maintenance of ER homeostasis and essential for larval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 2009;23:2215–2225. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-123737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaMonte G, et al. Mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum cyclic amine resistance locus (PfCARL) confer multidrug resistance. MBio. 2016;7:e00696–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00696-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magistrado, P. A., et Al. Plasmodium falciparum cyclic amine resistance locuS (PfCARL), a resistance mechanism for two distinct compound classes. ACS Infect. Dis. 2, 816–826 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]