Abstract

Background

Predicting mortality risk in patients is important in research settings. The Pitt bacteremia score (PBS) is commonly used as a predictor of early mortality risk in patients with bloodstream infections (BSIs). We determined whether the PBS predicts 14-day inpatient mortality in nonbacteremia carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections.

Methods

Patients were selected from the Consortium on Resistance Against Carbapenems in Klebsiella and Other Enterobacteriaceae, a prospective, multicenter, observational study. We estimated risk ratios to analyze the predictive ability of the PBS overall and each of its components individually. We analyzed each component of the PBS in the prediction of mortality, assessed the appropriate cutoff value for the dichotomized score, and compared the predictive ability of the qPitt score to that of the PBS.

Results

In a cohort of 475 patients with CRE infections, a PBS ≥4 was associated with mortality in patients with nonbacteremia infections (risk ratio [RR], 21.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 7.0, 68.8) and with BSIs (RR, 6.0; 95% CI, 2.5, 14.4). In multivariable analysis, the hypotension, mechanical ventilation, mental status, and cardiac arrest parameters of the PBS were independent risk factors for 14-day all-cause inpatient mortality. The temperature parameter as originally calculated for the PBS was not independently associated with mortality. However, a temperature <36.0°C vs ≥36°C was independently associated with mortality. A qPitt score ≥2 had similar discrimination as a PBS ≥4 in nonbacteremia infections.

Conclusions

Here, we validated that the PBS and qPitt score can be used as reliable predictors of mortality in nonbacteremia CRE infections.

Keywords: Pitt bacteremia score, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, mortality, risk score

In 475 patients with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections, the Pitt bacteremia score predicted 14-day mortality in patients with bacteremia as well as in patients with nonbacteremic infections. A dichotomized “quick” Pitt bacteremia score predicted mortality similarly well in nonbacteremic infections.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Al-Hasan and Baddour on pages 1834–7.)

The global spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections is an urgent threat to public health. CRE infections are associated with worse clinical outcomes and higher healthcare costs compared to infections with susceptible strains [1]. Patients with severe acute and chronic illnesses are most at risk for CRE infection and mortality [2–5]. Limited availability of effective antibiotic treatment further contributes to the high mortality associated with CRE infections [3, 6–8]. Well-designed observational studies complement randomized controlled trials to answer important questions in infections caused by CRE and other multidrug-resistant organisms. In such studies, a valid, reliable, and easily measured indicator of acute severity of illness may help to stratify patients by baseline risk of mortality.

The Pitt bacteremia score (PBS) is widely used in infectious disease research as a severity of acute illness index. It ranges from 0 to 14 points, with a score ≥4 commonly used as an indicator of critical illness and increased risk of death [9]. The PBS was originally developed to predict mortality in patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection (BSI) and has since been shown to be predictive in patients with BSIs due to other gram-negative, gram-positive, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria as well as Candida spp. [9–19]. However, use of the PBS in nonbacteremia infections has not been validated. Furthermore, researchers have used different cutoff levels to indicate increased risk of mortality.

In this study, we determined whether the PBS predicts 14-day inpatient mortality among patients with nonbacteremia CRE infections as well as BSIs. We then assessed the contribution of each component of the PBS to the prediction of mortality in this study population, as well as the most appropriate cutoff level for dichotomization of the score. Finally, we compared the predictive ability of the PBS to that of the qPitt score [20] in nonbacteremia CRE infections.

METHODS

CRACKLE-1 Study

The Consortium on Resistance Against Carbapenems in Klebsiella and Other Enterobacteriaceae (CRACKLE-1) is a prospective, multicenter study of hospitalized patients with CRE [21–24]. All hospitalized patients with a CRE cultured from any specimen source from December 2011 through June 2016 were included and followed until hospital discharge. From December 2011 through December 2014, only data on patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae were collected; from January 2015 through June 2016, patients with any CRE were included. The 2012 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of CRE was used, as previously described [2]. On available isolates, detection of carbapenemase genes by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and molecular strain typing by repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (rep-PCR) was performed, as previously described [2]. All clinical data were obtained from the electronic medical record. Each health system involved in this study had approval from its respective institutional review board.

Study Population and Measures

A culture episode was defined as a clinical culture with growth of CRE from any anatomical site. Patients with BSIs were analyzed as such regardless of the primary source. Infections were distinguished from colonization using standard definitions, as previously described [2]. Culture episodes were excluded if the admission date, discharge date, first positive culture date, culture source, or posthospital disposition was missing.

For this analysis, each unique patient was included once at the time of the last CRE-positive culture episode. For each patient, baseline was defined as the date of collection of the CRE-positive culture that was included in this analysis. The outcome of interest was 14-day all-cause inpatient mortality, measured from baseline. For analysis purposes, patients discharged to hospice within 14 days of baseline were classified as deceased at discharge. The PBS was calculated for each patient at baseline [9]. The hypotension, mechanical ventilation, mental status, and maximum temperature parameters of the PBS were measured on the baseline date. For each variable, the worst reading on the calendar day of the index culture was recorded. Cardiac arrest was considered present if it occurred on the baseline date or within the previous 48 hours.

The qPitt score incorporates all 5 components of the PBS as binary variables, with temperature dichotomized as <36.0°C vs ≥36.0°C and mental status dichotomized as altered vs normal. Additionally, the respiratory failure parameter includes either mechanical ventilation or respiratory rate ≥25/min. The maximum qPitt score is 5, with a score ≥2 indicating increased risk of mortality [20]. Respiratory rate was not measured in our cohort; therefore, the respiratory parameter used to calculate the qPitt score included only mechanical ventilation.

Statistical Analyses

We estimated the predictive ability of the PBS overall and for each of its components individually on 14-day inpatient mortality. The PBS was analyzed both as an ordinal and as a dichotomized variable [9]. To determine the most appropriate cutoff value for the dichotomized PBS, we calculated the sensitivity and specificity at each possible cutoff value. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using modified Poisson regression models with robust errors [25]. We then compared the discrimination of the qPitt score to that of the PBS in nonbacteremia infections. Predictive discrimination of the models was evaluated using the concordance (c) statistic (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) [26], where a value of 0.5 indicates no predictive discrimination and a value of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination. A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Population and 14-Day Inpatient Mortality

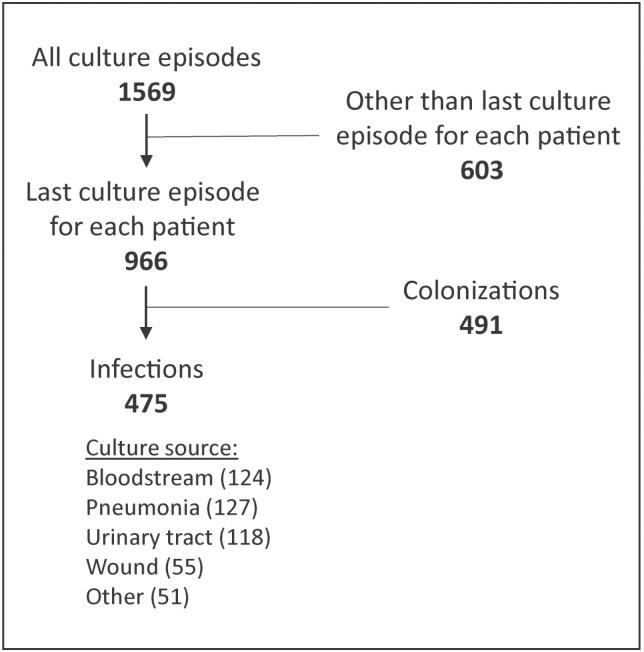

A total of 1627 culture episodes were available for analysis; 58 (3.6%) were excluded due to missing data. The 1569 remaining culture episodes corresponded to 966 unique patients. After selecting the last culture episode from each of the 966 patients, 475 (49%) were classified as infections and were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of culture episodes.

The median age of patients was 63 years (interquartile range [IQR], 51, 74), and 48% were male (Table 1). Overall 14-day inpatient mortality was 19%. Fourteen-day mortality was highest in patients with BSIs (28%) and pneumonia (25%). Patients with wound, urinary, and other infections had 14-day mortality of 16%, 6%, and 14%, respectively. Overall 14-day mortality decreased over the study period, from 26% in 2012 to 10% in 2016. When analyzed by infection type, the decreasing trend in mortality was seen in BSIs and pneumonia only. The median baseline PBS was 4 (IQR, 4, 6) among patients who died within 14 days and 2 (IQR, 1, 4) among patients who survived. Comorbidities were common, with a median Charlson comorbidity index of 3 among patients who died as well as those who survived.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae–positive Culture, Stratified by 14-Day Inpatient Mortality

| Characteristic | Survived (Median [IQR] or n [%]) (n = 385) |

Dieda (Median [IQR] or n [%]) (n = 90) |

Total (Median [IQR] or n [%]) (N = 475) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63 (51–73) | 63 (53–75) | 63 (51–74) |

| Male | 185 (48) | 43 (48) | 228 (48) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 3 (1–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (1–5) |

| Culture source | |||

| Blood | 89 (23) | 35 (39) | 124 (26) |

| Respiratory | 95 (25) | 32 (36) | 127 (27) |

| Urine | 111 (29) | 7 (8) | 118 (25) |

| Wound | 46 (12) | 9 (10) | 55 (12) |

| Other | 44 (11) | 7 (8) | 51 (11) |

| Pitt bacteremia score | 2 (1–4) | 4 (4–6) | 3 (1–4) |

| Hypotension | 181 (47) | 79 (88) | 260 (55) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 180 (47) | 76 (84) | 256 (54) |

| Cardiac arrest | 4 (1) | 13 (14) | 17 (4) |

| Maximum temperature (°C) | |||

| 36.1–38.9 | 334 (87) | 68 (76) | 402 (85) |

| 35.1–36.0 or 39.0–39.9 | 46 (12) | 18 (20) | 64 (13) |

| ≤35.0 or ≥40.0 | 5 (1) | 4 (4) | 9 (2) |

| Mental status | |||

| Normal | 279 (72) | 62 (69) | 341 (72) |

| Disoriented | 61 (16) | 6 (7) | 67 (14) |

| Stuporous | 31 (8) | 11 (12) | 42 (9) |

| Comatose | 14 (4) | 11 (12) | 25 (5) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

aInpatient mortality within 14 days of baseline (collection date of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae–positive culture).

Prior to 1 January 2015, K. pneumoniae was isolated from 178/182 (98%) patients. From January 2015 through June 2016, K. pneumoniae was isolated from 249/293 (85%) patients. The remaining 48 isolates were Enterobacter sp. (25), Morganella sp. (7), Escherichia coli (3), Citrobacter sp. (2), Serratia sp. (1), and other CRE (10). Among patients with BSIs, 89% of isolates were K. pneumoniae, and among patients with nonbacteremia infections, 90% of isolates were K. pneumoniae. Of 284 isolates tested, 239 (84%) were found to carry carbapenemase genes.

Evaluation of Cutoff Level for Dichotomized PBS

To determine the most appropriate cutoff value for dichotomization of the PBS, we plotted the observed mortality in the cohort by PBS (Figure 2). As the PBS increased from 3 to 4, mortality increased markedly and continued in an increasing trend as the PBS increased above 4. Additionally, the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity − 1) was maximized when the PBS was dichotomized at <4 vs ≥4 (Supplementary Table 1). The most appropriate cutoff level was <4 vs ≥4 for both BSIs and nonbacteremia infections (Figure 2) and after stratifying by Charlson comorbidity index or by time period (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

Observed mortality by Pitt bacteremia score for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia and nonbacteremia infections. Scores ≥7 combined into a single category.

PBS in Nonbacteremia Infections

Among all patients, PBS ≥4 was strongly associated with 14-day inpatient mortality (RR, 12.2; 95% CI, 6.0, 24.6). In patients with nonbacteremia infections, the RR was 21.9 (95% CI, 7.0, 68.8), and in patients with BSIs, the RR was 6.0 (95% CI, 2.5, 14.4). Survival curves for the dichotomized PBS in both groups of patients are shown in Figure 3. Separation between the curves for PBS ≥4 vs <4 was similar for BSIs and nonbacteremia infections, and the log-rank test was significant (P < .0001) for both groups. However, patients with nonbacteremia infections had significantly lower mortality than was observed in the corresponding bacteremic patients (P = .03 for patients with PBS <4; P = .02 for patients with PBS ≥4).

Figure 3.

Survival curves for Pitt bacteremia score ≥4 vs <4. Abbreviation: PBS, Pitt bacteremia score.

For all infections, a PBS ≥4 had high sensitivity (0.91) for prediction of 14-day all-cause mortality. The positive predictive value (ie, the proportion of patients with PBS ≥4 who died within 14 days) was 0.38, and the negative predictive value (ie, the proportion of patients with PBS <4 who survived at least 14 days) was 0.97. The values were similar for BSIs and nonbacteremia infections (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value, and Negative Predictive Value for Pitt Bacteremia Score ≥4 in Prediction of 14-Day Mortality, by Infection Type

| Infection Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.97 |

| Bloodstream infection | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.92 |

| All nonbacteremia | 0.95 | 0.65 | 0.34 | 0.98 |

| Respiratory | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 1.00 |

| Urinary | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.24 | 1.00 |

| Other nonbacteremia | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.96 |

Contributions of Individual Components of the PBS

When analyzed separately, each of the 5 components of the PBS was statistically significantly associated with increased risk of 14-day mortality (Table 3). With all 5 components included in a multivariable model, temperature was no longer statistically associated with mortality. Further analysis showed that mortality for all infection types increased with temperatures <36°C (Supplementary Figure 3). After dichotomization of temperature as <36.0°C vs ≥36.0°C, a temperature <36.0°C was significantly associated with mortality in a multivariable model (RR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.4, 3.5). However, the predictive ability of the model (as measured by the c-statistic) was not significantly improved with the inclusion of the temperature parameter, either as a dichotomized variable or classified as per the original PBS.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Risk Ratios of Pitt Bacteremia Score Components on 14-Day Inpatient Mortality

| 14-Day Inpatient Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Weight | Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

| Hypotensiona,b | 2 | 5.9 (3.2, 10.9) | <.0001 |

| Mechanical ventilationb | 2 | 4.6 (2.7, 7.8) | <.0001 |

| Cardiac arrestc | 4 | 4.5 (3.2, 6.3) | <.0001 |

| Mental status (referent: normal)b | |||

| Disoriented | 1 | 0.49 (0.22, 1.1) | .08 |

| Stuporous | 2 | 1.4 (0.83, 2.5) | .2 |

| Comatose | 4 | 2.4 (1.5, 4.0) | .0005 |

| Maximum temperature (°C)b (referent: 36.1–38.9) | |||

| 35.1–36.0 or 39.0–39.9 | 1 | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | .03 |

| ≤35.0 or ≥40.0 | 2 | 2.6 (1.2, 5.6) | .01 |

| Pitt bacteremia score ≥4 (N = 475) | 12.2 (6.0, 24.6) | <.0001 | |

| Bacteremic infections (n = 124) | 6.0 (2.5, 14.4) | <.0001 | |

| Nonbacteremic infections (n = 351) | 21.9 (7.0, 68.8) | <.0001 | |

aAn acute hypotensive event with drop in systolic blood pressure >30 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure >20 mm Hg or requirement for intravenous vasopressor agents or systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg.

bOn day of collection of index culture.

cOn day of or within 48 hours preceding collection of index culture.

Comparison of the PBS and the qPitt Score in Nonbacteremia Infections

The qPitt score (calculated without the respiratory rate component) ≥2 was strongly associated with 14-day mortality (RR, 14.2; 95% CI, 5.2, 38.5) in nonbacteremia infections. Discrimination was very similar between the PBS and qPitt score models (c-statistic = 85.3 and 85.1, respectively). After dichotomization at 4 and 2, respectively, the c-statistic was 79.9 for the PBS and 76.9 for the qPitt score. Sensitivity and specificity were similar between the dichotomized PBS and qPitt scores (sensitivity = 94.6 and 92.7, respectively; specificity = 65.2 and 60.1, respectively). Notably, the binary mental status parameter (altered vs normal) was not predictive of mortality in our cohort, whereas mental status as classified for the original PBS added substantially to the predictive ability of the model.

DISCUSSION

Many scoring systems have been developed to grade severity of illness, some of which are complex and require special software to calculate. Complex scores can perform well in certain populations but be poorly calibrated in others. Furthermore, they become less well calibrated over time and require periodic updating. Some of the most commonly used scoring systems were developed in the 1980s and 1990s, such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, the 2nd Simplified Acute Physiology Score, and the Mortality Prediction Model. These scores have relatively few parameters and are easily calculated. The PBS has the fewest parameters and is the simplest to calculate of these commonly used scores. In a study of patients with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia, the PBS outperformed the Pneumonia Severity Index, the CURB-65 and CRB-65 score, the modified American Thoracic Society score, the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society guideline criteria for severity of illness, and the APACHE II score in prediction of mortality [27]. Of note, a cutoff PBS >4 was used in this study, rather than PBS ≥4. A study of intensive care unit patients with sepsis also concluded that the PBS predicted mortality better than the APACHE II score [28].

In our cohort, the dichotomized PBS had high sensitivity in predicting 14-day all-cause inpatient mortality for nonbacteremia infections as well as BSIs. We also showed that dichotomization at ≥4 was appropriate for both BSIs and nonbacteremia infections. While our observation that PBS also predicts mortality in nonbacteremia infections is not surprising, it allows for the broader use of this simple yet powerful score in clinical infectious disease research.

An abbreviated version of the PBS, the qPitt score, was recently derived in a cohort of hospitalized patients with gram-negative BSIs [20]. Here, we evaluated the qPitt score in nonbacteremic infections. The characteristics of the qPitt score were similar to the PBS in nonbacteremic infections, suggesting that the qPitt score, like the PBS, can also be used for mortality risk prediction in nonbacteremic infections.

Mortality risk scores can be used in several ways in infectious disease research. The use of standardized risk scores allows for the comparison of populations across various studies. In addition, risk scores can be used as a covariate in multivariable models or to stratify analyses. Finally, in prospective studies, risk scores can be used to target a population most likely to benefit from a given intervention. For example, in the INCREMENT study, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez et al found that patients with CRE bacteremia who had higher risk for mortality had a disproportionate benefit of combination therapy [29].

In our cohort, temperature at the time of infection was associated with mortality in univariable analysis; however, in a multivariable model, temperature did not add predictive power to the other variables in the PBS. Whether this is specific to the CRACKLE-1 cohort or can be generalized to other populations with infection remains to be determined. A recent study on solid organ transplant recipients with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial BSI found that temperature ≥40°C was associated with mortality in univariable, but not multivariable, analysis [30]. Another study showed that increased body temperature in the emergency department was strongly associated with improved outcomes in patients with sepsis [31].

Novel treatment options became available during the study period, which may have contributed to improved outcomes seen in the later years of the study period. Most notable of these was the introduction of ceftazidime-avibactam [32]. However, improved insights in polymyxin dosing and use of combination therapy may also have played a role [33–36]. Nevertheless, the association between the PBS and mortality was similar in both periods.

There are several limitations to this study. We used the well-defined CRACKLE-1 cohort as this cohort has a known high acuity of illness at the time of positive culture. However, the majority of isolates were K. pneumoniae, which may limit generalizability to other CRE infections. The participating hospitals were primarily in the Great Lakes region of the United States. Although participating hospitals ranged from small community-based hospitals to large tertiary care centers, the patient population may be systematically different from that in other locations, which may further limit generalizability. Also, infections were categorized using standardized definitions, which have high specificity and low sensitivity. Some patients with infection may therefore have been misclassified as colonization and excluded from the analysis. Some patients classified as nonbacteremia may not have received adequate blood cultures and could therefore be misclassified. Finally, further studies will be needed to explore the predictive ability of the PBS in nonbacteremia infections due to other pathogens and in different types of cohorts.

In summary, this analysis shows that among our cohort of patients with CRE infections, the PBS is at least as strongly predictive of 14-day mortality in nonbacteremia infections as with BSIs and therefore is a useful tool for predicting high risk of mortality in patients with infection at any site. We have also shown that the qPitt score predicts mortality in patients with nonbacteremia infections in this cohort.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Disclaimer. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the NIH under awards UM1AI104681 and R21AI114508 and by funding to D. v. D. from the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland (UL1TR000439) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. V. G. F. was supported by a Mid-Career Mentoring award (K24-AI093969) from the NIH. In addition, research reported in this publication was supported in part by the NIAID of the NIH under awards R21AI114508 (D. v. D. and R. A. B.) and R01AI100560, R01AI063517, and R01AI072219 (R. A. B.). This study was supported in part by funds and/or facilities provided by the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs award 1I01BX001974 to R. A. B. from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center Veterans Integrated Service Network 10 (R. A. B.). Further support came from the Research Program committees of the Cleveland Clinic (D. v. D.), an unrestricted research grant from the STERIS Corporation (D. v. D.). Y. D. was supported by research awards R01AI104895, R21AI123747, and R21AI135522 from the NIH. K. S. K. is supported by the NIAID (Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases protocol 10-0065 and R01AI119446-01).

Potential conflicts of interest. S. E.: grants from NIAID/NIH during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Takeda/Millennium, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, Achaogen, Huntington’s Study Group, ACTTION, Genentech, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, the American Statistical Association, the US Food and Drug Administration, Osaka University, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center of Japan, Society for Clinical Trials, Statistical Communications in Infectious Diseases (DeGruyter), AstraZeneca, Teva, Austrian Breast & Colorectal Cancer Study Group/Breast International Group and the Alliance Foundation Trials, Zeiss, Dexcom, American Society for Microbiology, Taylor and Francis, Claret Medical, Vir, Arrevus, Five Prime, Shire, Alexion, Gilead, Spark, Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, Nuvelution, Tracon, Deming Conference, Antimicrobial Resistance and Stewardship Conference, World Antimicrobial Congress, WAVE, Advantagene, Braeburn, Cardinal Health, Lipocine, Microbiotix, and Stryker, all outside the submitted work. S. S. R.: research support from bioMerieux, BD Diagnostics, Roche, Hologic, Diasorin, Roche, Affinity Biosensors, Accelerate, OpGen, and BioFire. R. A. B.: grant/research support from Achaogen, Allecra, Entasis, Merck, Roche, Shionogi, and Wockhardt. V. G. F.: served as chair of the V710 Scientific Advisory Committee (Merck); has received grant support from Cerexa/Actavis/Allergan, Pfizer, Advanced Liquid Logics, NIH, MedImmune, Basilea Pharmaceutica, Karius, ContraFect, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Genentech; has NIH Small Business Technology Transfer/Small Business Innovation Research grants pending with Affinergy, Locus, and Medical Surface, Inc; has been a consultant for Achaogen, AmpliPhi Biosciences, Astellas Pharma, Arsanis, Affinergy, Basilea Pharmaceutica, Bayer, Cerexa Inc., ContraFect, Cubist, Debiopharm, Durata Therapeutics, Grifols, Genentech, MedImmune, Merck, the Medicines Company, Pfizer, Novartis, NovaDigm Therapeutics Inc, Theravance Biopharma, Inc, and XBiotech; has received honoraria from Theravance Biopharma, Inc and Green Cross; and has a patent pending in sepsis diagnostics. D. v. D. served on advisory boards for Actavis, Tetraphase, Sanofi-Pasteur, MedImmune, Astellas, Merck, Allergan, T2Biosystems, Roche, Achaogen, Neumedicine, and Shionogi and has received research funding from Steris Inc and Scynexis. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: IDWeek. San Francisco, CA, 3–7 October 2018.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance—global report on surveillance. Available at: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en Accessed 1 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Duin D, Perez F, Rudin SD, et al. Surveillance of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: tracking molecular epidemiology and outcomes through a regional network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:4035–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kontopidou F, Giamarellou H, Katerelos P, et al. ; Group for the Study of KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections in Intensive Care Units Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae among patients in intensive care units in Greece: a multi-centre study on clinical outcome and therapeutic options. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20:O117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nouvenne A, Ticinesi A, Lauretani F, et al. Comorbidities and disease severity as risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae colonization: report of an experience in an internal medicine unit. PLoS One 2014; 9:e110001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, De Rosa FG, et al. ; ISGRI-SITA (Italian Study Group on Resistant Infections of the Società Italiana Terapia Antinfettiva) Infections caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: differences in therapy and mortality in a multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70:2133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Falcone M, Russo A, Iacovelli A, et al. Predictors of outcome in ICU patients with septic shock caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 22:444–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:785–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rojas LJ, Salim M, Cober E, et al. ; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group Colistin resistance in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: laboratory detection and impact on mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:711–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chow JW, Yu VL. Combination antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for gram-negative bacteraemia: a commentary. Int J Antimicrob Agents 1999; 11:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hilf M, Yu VL, Sharp J, Zuravleff JJ, Korvick JA, Muder RR. Antibiotic therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: outcome correlations in a prospective study of 200 patients. Am J Med 1989; 87:540–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chow JW, Fine MJ, Shlaes DM, et al. Enterobacter bacteremia: clinical features and emergence of antibiotic resistance during therapy. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korvick JA, Bryan CS, Farber B, et al. Prospective observational study of Klebsiella bacteremia in 230 patients: outcome for antibiotic combinations versus monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1992; 36:2639–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Korvick JA, Marsh JW, Starzl TE, Yu VL. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in patients undergoing liver transplantation: an emerging problem. Surgery 1991; 109:62–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hill PC, Birch M, Chambers S, et al. Prospective study of 424 cases of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: determination of factors affecting incidence and mortality. Intern Med J 2001; 31:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu VL, Chiou CC, Feldman C, et al. ; International Pneumococcal Study Group An international prospective study of pneumococcal bacteremia: correlation with in vitro resistance, antibiotics administered, and clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee C-C, Wang J-L, Lee C-H, et al. Age-related trends in adults with community-onset bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:e01050–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Su TY, Ye JJ, Hsu PC, Wu HF, Chia JH, Lee MH. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in cefepime-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2015; 48:175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nguyen MH, Peacock JE Jr, Tanner DC, et al. Therapeutic approaches in patients with candidemia. Evaluation in a multicenter, prospective, observational study. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:2429–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vaquero-Herrero MP, Ragozzino S, Castaño-Romero F, et al. The Pitt bacteremia score, Charlson comorbidity index and chronic disease score are useful tools for the prediction of mortality in patients with Candida bloodstream infection. Mycoses 2017; 60:676–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Battle SE, Augustine MR, Watson CM, et al. Derivation of a quick Pitt bacteremia score to predict mortality in patients with gram-negative bloodstream infection. Infection 2019 doi:10.1007/s15010-019-01277-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Duin D, Cober E, Richter SS, et al. Residence in skilled nursing facilities is associated with tigecycline nonsusceptibility in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015; 36:942–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Duin D, Cober E, Richter SS, et al. Impact of therapy and strain type on outcomes in urinary tract infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70:1203–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Messina JA, Cober E, Richter SS, et al. ; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group Hospital readmissions in patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37:281–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Duin D, Cober ED, Richter SS, et al. Tigecycline therapy for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) bacteriuria leads to tigecycline resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20:O1117–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159:702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrell FE Jr, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA 1982; 247:2543–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feldman C, Alanee S, Yu VL, et al. ; International Pneumococcal Study Group Severity of illness scoring systems in patients with bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia: implications for the intensive care unit care. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; 15:850–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhee JY, Kwon KT, Ki HK, et al. Scoring systems for prediction of mortality in patients with intensive care unit-acquired sepsis: a comparison of the Pitt bacteremia score and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scoring systems. Shock 2009; 31:146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Salamanca E, de Cueto M, et al. ; Investigators from the REIPI/ESGBIS/INCREMENT Group A predictive model of mortality in patients with bloodstream infections due to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91:1362–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qiao B, Wu J, Wan Q, Zhang S, Ye Q. Factors influencing mortality in abdominal solid organ transplant recipients with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sundén-Cullberg J, Rylance R, Svefors J, Norrby-Teglund A, Björk J, Inghammar M. Fever in the emergency department predicts survival of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock admitted to the ICU. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:591–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Duin D, Lok JJ, Earley M, et al. ; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group Colistin versus ceftazidime-avibactam in the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:163–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tumbarello M, Viale P, Viscoli C, et al. Predictors of mortality in bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae: importance of combination therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:943–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Marangos M, Christofidou M, et al. Risk factors for infection and predictors of mortality among patients with KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Scand J Infect Dis 2014; 46:642–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grégoire N, Mimoz O, Mégarbane B, et al. New colistin population pharmacokinetic data in critically ill patients suggesting an alternative loading dose rationale. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:7324–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ortwine JK, Sutton JD, Kaye KS, Pogue JM. Strategies for the safe use of colistin. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2015; 13:1237–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.