Abstract

Background

Oral candidiasis (OC) associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection occurs commonly and recurs frequently, often presenting as an initial manifestation of the disease. Left untreated, these lesions contribute considerably to the morbidity associated with HIV infection. Interventions aimed at preventing and treating HIV‐associated oral candidal lesions form an integral component of maintaining the quality of life for affected individuals.

Objectives

To determine the effects of any intervention in preventing or treating OC in children and adults with HIV infection.

Search methods

The search strategy was based on that of the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group. The following electronic databases were searched for randomised controlled trials for the years 1982 to 2005: Medline, AIDSearch, EMBASE and CINAHL. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were also searched through May 2005. The abstracts of relevant conferences, including the International Conferences on AIDS and the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, as indexed by AIDSLINE, were also reviewed. The strategy was iterative, in that references of included studies were searched for additional references. All languages were included.

The updated database search was done for the period 2005 up to 2009. The following databases were searched: Medline, EMBASE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library. AIDSearch was not searched for the updated search as it ceased publication during 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of palliative, preventative or curative therapy were considered, irrespective of whether the control group received a placebo. Participants were HIV positive adults and children.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the trials and extracted data. Study authors were contacted for additional data where necessary.

Main results

For the first publication of the review in 2006, forty studies were retrieved. Twenty eight trials (n=3225) met inclusion criteria. During the update search for the review a, further six studies were identified. Of these, five met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The review now includes 33 studies (n=3445): 22 assessing treatment and 11 assessing prevention of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Six studies were done in developing countries, 16 in the United States of America and the remainder in Europe.

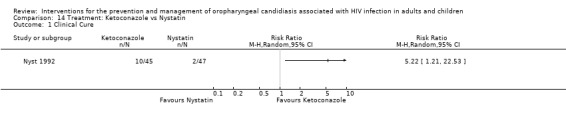

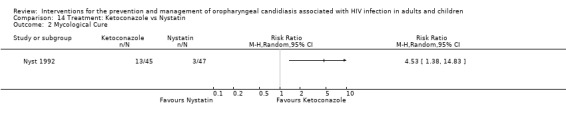

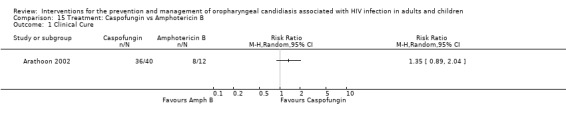

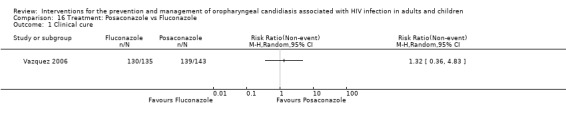

Treatment Treatment was assessed in the majority of trials looking at both clinical and mycological cures. In the majority of comparisons there was only one trial. Compared to nystatin, fluconazole favoured clinical cure in adults (1 RCT; n=167; RR 1.69; 95% CI 1.27 to 2.23). There was no difference with regard to clinical cure between fluconazole compared to ketoconazole (2 RCTs; n=83; RR 1.27; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.66), itraconazole (2 RCTs; n=434; RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.16), clotrimazole (2 RCTs; n=358; RR 1.14; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.42) or posaconazole (1 RCT; n=366; RR1.32; 95% CI 0.36 to 4.83). Two trials compared different dosages of fluconazole with no difference in clinical cure. When compared with clotrimazole, both fluconazole (2 RCTs; n=358; RR 1.47; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.87) and itraconazole (1 RCT; n=123; RR 2.20; 95% CI 1.43 to3.39) proved to be better for mycological cure. Both gentian violet (1 RCT; n=96; RR 5.28; 95% CI 1.23 to 22.55) and ketoconazole (1 RCT; n=92; RR 5.22; 95% CI 1.21 to 22.53) were superior to nystatin in bringing about clinical cure. A single trial compared gentian violet with lemon juice and lemon grass with no significant difference in clinical cure between the groups. Prevention Successful prevention was defined as the prevention of a relapse while receiving prophylaxis. Fluconazole was compared with placebo in five studies (5 RCTs; n=599; RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.5 to 0.74) and with no treatment in another (1 RCT; n=65; RR 0.16; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.34). In both instances the prevention of clinical episodes was favoured by fluconazole. Comparing continuous fluconazole treatment with intermittent treatment (2 RCTs; n=891; RR 0.65; 95% CI 0.23 to 1.83), there was no significant difference between the two treatment arms. Chlorhexidine was compared with normal saline in a single study with no significant difference between the treatment arms.

Authors' conclusions

Five new studies were added to the review, but their results do not alter the final conclusion of the review.

Implications for practice Due to there being only one study in children, it is not possible to make recommendations for treatment or prevention of OC in children. Amongst adults, there were few studies per comparison. Due to insufficient evidence, no conclusion could be made about the effectiveness of clotrimazole, nystatin, amphotericin B, itraconazole or ketoconazole with regard to OC prophylaxis. In comparison to placebo, fluconazole is an effective preventative intervention. However, the potential for resistant Candida organisms to develop, as well as the cost of prophylaxis, might impact the feasibility of implementation. No studies were found comparing fluconazole with other interventions. The direction of findings suggests that ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole and clotrimazole improved the treatment outcomes.

Implications for research It is encouraging that low‐cost alternatives are being tested, but more research needs to be on in this area and on interventions like gentian violet and other less expensive anti‐fungal drugs to treat OC. More well‐designed treatment trials with larger samples are needed to allow for sufficient power to detect differences in not only clinical, but also mycological, response and relapse rates. There is also a strong need for more research to be done on the treatment and prevention of OC in children as it is reported that OC is the most frequent fungal infection in children and adolescents who are HIV positive. More research on the effectiveness of less expensive interventions also needs to be done in resource‐poor settings. Currently few trials report outcomes related to quality of life, nutrition, or survival. Future researchers should consider measuring these when planning trials. Development of resistance remains under‐studied and more work must be done in this area. It is recommended that trials be more standardised and conform more closely to CONSORT.

Plain language summary

Interventions for the prevention and management of oral thrush associated with HIV infection in adults and children

Oral candidiasis (thrush) associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection occurs commonly and recurs frequently, often presenting as an initial manifestation of the disease. Interventions aimed at preventing and treating HIV‐associated oral thrush form an integral component of maintaining the quality of life for affected individuals. This review evaluated the effects of interventions in preventing or treating oral thrush in children and adults with HIV infection. Thirty three trials (n=3445) were included. Twenty two trials investigated treatment and eleven trials investigate prevention. There was no difference with regard to clinical cure between fluconazole compared to ketoconazole, itraconazole, clotrimazole and posaconazole. Fluconazole, gentian violet and ketoconazole were superior to nystatin. Compared to placebo and no treatment, fluconazole was effective in preventing clinical episodes from occurring. Continuous fluconazole was better than intermittent treatment. Insufficient evidence was found to come to any conclusion about the effectiveness of clotrimazole, nystatin, amphotericin B, itraconazole, ketoconazole or chlorhexidine with regard to OC prophylaxis.

Background

Description of the condition

Oral candidiasis (OC) associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection occurs commonly and recurs frequently (Arribas 2000; Greenspan 1992; Gennaro 2008; Reznik 2005), often presenting as an initial manifestation of the disease (Coogan 2005; Epstein 1998; Nittayananta 1997; Rachanis 2001). Though Candida albicans is most commonly implicated, other organisms have also been identified. If left untreated these lesions contribute considerably to the morbidity associated with HIV infection. Interventions aimed at preventing and treating HIV‐associated oral candidal lesions form an integral component of maintaining the quality of life for affected individuals. For brevity's sake, the term oral HIV lesions will be used for oropharyngeal infections associated with HIV/AIDS infection.

The spectrum of oral HIV lesions seen include those of fungal, viral, bacterial and neoplastic origin. This review deals with oral candidiasis, the most common oral HIV lesion seen in both children and adults (Ramos‐Gomez 1999; Williams 1993). Four forms occur (Williams 1993) ‐ pseudomembranous candidiasis, erythematous candidiasis, angular chelitis and mixed candidal lesions. OC has been found to occur more commonly in those with advancing HIV infection (Klein 1984), often requiring more aggressive forms of treatment. The presence of OC, which can be painful, may lead to a reduction in food intake (Oude Lashof 2004), or a reduction in the correct kinds of food, with subsequent malnutrition, which may compromise an already ill patient even more. Additionally, OC has been found to lead to the loss of taste and smell in HIV‐infected patients and can subsequently impair the intake of food and contribute to wasting (Heald 1997; Paillaud 2004). Xerostomia, a reduction in the flow of saliva, is a common occurrence (Arendorf 1998). It may occur as a result of the disease process or secondary to medications used. Not only does this condition render the normal protective components of saliva less effective, but it also interferes with the solubility of topical antifungals. It has also been found that concomitant drug therapy with antibiotics may influence the colonization and proliferation of the yeast within the oral cavity.

Description of the intervention

The treatment of mucosal fungal infections is dominated by the azole compounds, which can be used either topically or systemically. The antifungal agents for the treatment of OC in adults, together with their recommended dosages, are listed in Table 26. Similarly the antifungal agents for the treatment of OC in children are listed in Table 27, together with their dosages, as recommended by Ramos‐Gomez 1999. Mucosal diseases do however have the propensity for some patients to suffer from repeated relapses (Rex 2000). The suppression of OC is possible with the use of topical agents such as clotrimazole or nystatin, or with systemic agents such as ketoconazole or fluconazole (Gallant 1994; Pankhurst 2005). The routine use of prophylactic treatment in patients with OC may lead to the development of resistance, especially to the azole antifungal agents like fluconazole. Resistance has been found to develop in patients with advanced HIV disease or after repeated or long‐term therapy for OC (Epstein 1998). There is however an overall lack of data on resistance following antifungal usage (Patton 2001; Ioannidis 2005).

1. Antifungal Agents for use in Adults.

| Administration | Drug | Form | Dosage |

| Topical | Amphotericin‐B | Lozenge | 10 000 iu dissolved slowly in the mouth 3‐4 times a day for a minimum of 2 weeks |

| Topical | Nystatin | Cream | Apply to affected area twice a day |

| Topical | Nystatin | Oral suspension | 20ml 4 times a day; continue to use for several days post clinical resolution |

| Topical | Nystatin | Pastille | Dissolve tablet in mouth 5 times a day |

| Topical | Clotrimazole | Solution | 5ml 3‐4 times a day for 2 weeks minimum |

| Topical | Clotrimazole | Cream | apply to affected area 2‐3 times a day for 3‐4 weeks |

| Topical | Miconazole | Oral gel | apply to the affected area 3‐4 times a day |

| Topical | Miconazole | Cream | Apply twice a day and continue to use 10‐14 days after lesions heal |

| Systemic | Fluconazole | 150mg Capsules | 150mg stat or one 150mg capsule once a day for 2‐3 weeks |

| Systemic | Ketaconazole | 200mg Tablets | One to two tablets twice a day with food for 2 weeks |

| Systemic | Itraconazole | 100mg Capsules | one capsule per day taken immediately after meals for 2 weeks |

| Topical | Chlorhexidine gluconate (0,2%) | Mouthwash | 10ml to be swirled in the mouth for 1 timed minute and then spat out |

| Topical | Gentian Violet (0,5%) | Aqueous solution | Paint on affected area(s) of mouth three times daily |

2. Antifungal Agents for use in Children.

| Administration | Drug | Form | Dosage |

| Topical | Nystatin | Oral suspension | 1 to 5 ml suspension five times per day |

| Topical | Nystatin | 100 000 U/ml vaginal tablets | 1 in nipple TID |

| Topical | Clotrimazole | 10 mg troches | five times per day |

| Topical | Clotrimazole | 100 000 u/ml vaginal tablets | 1 in nipple TID |

| Systemic | Fluconazole | 2‐5 mg per kg | Once a day |

| Systemic | Ketoconazole | 4‐6 mg per kg | Once or twice a day |

How the intervention might work

While antifungals are available as either topical or systemic agents, the choice of treatment is influenced by many variables. Current criteria for prescription of treatment are either arbitrary or determined by availability and affordability within particular clinical settings, or based on specified hospital protocols. In resource‐poor settings the availability is dependent on the cost of treatment.

Whilst antiretroviral therapy may not cure OC, evidence suggests that individuals on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) have less frequent and severe occurrences (Munro 2002; Schmidt‐West 2000). An observational cohort study, Arribas 2000 found that in patients with advanced HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy including a protease inhibitor, had a positive impact on OC. Yang 2006 investigated the effect of prolonged HAART on OC and found that it is highly effective in decreasing OC in association with a rise in CD4+ lymphocyte count. It has been reported that the risk of having OC can be halved in patients treated with HAART (Hodgson 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review evaluated the current evidence about interventions for the prevention and management of oro‐pharyngeal candidiasis associated with HIV infection in both adults and children. The differences, as well as the similarities, between the developing and the developed world were taken into account where possible when evaluating the available evidence.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine the effects of any intervention in preventing and treating oropharyngeal candidiasis in children and adults with HIV infection, by reviewing randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs) only.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

For the primary purpose of determining the effects of any given intervention, only randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs) of palliative, preventive or curative therapy were considered, irrespective of whether the control group received a placebo. Quasi‐randomised trials were excluded.

Types of participants

HIV‐positive adults and children (We defined children according to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) as being ≤13 years and adolescents or adults as being > 13 years, Osmond 1998).

Participants were receiving one or more of the following:

Treatment for OC;

Prophylactic treatment for OC;

HAART.

Types of interventions

Any intervention aimed at preventing, treating or palliating HIV‐associated OC.

These included:

HAART;

Traditional medicines;

Scaling and Polishing, curettage;

A combination of the above.

A comparison of any of these interventions against placebo or no treatment or another drug or intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Presence or absence of clinical lesions (Williams 1993)

Severity of the lesions (as defined by the study)

Microbiological measures e.g. candidal counts.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes:

Quality of life indicators (as defined by study)

Any adverse events such as hypersensitivity and development of resistant strains were reported if recorded.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The search strategy was based on that of the HIV/AIDS Cochrane Review Group. For the first review publication, the following electronic databases were searched 13 May 2005 for RCTs for the years 1982 to 2005: Medline; AIDSearch; EMBASE and CINAHL. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library were also searched through May 2005.

The abstracts of relevant conferences, including the International Conferences on AIDS and the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, as indexed by AIDSearch, were also searched. The reference lists of all review articles and primary articles identified were also searched. The abstracts of the International Conference on AIDS and STDs in Africa (ICASA) were not reviewed as we were unable to obtain access to the abstracts of the past conferences.

The search strategy was iterative, in that references of included studies were searched for additional references. All languages were included.

A search was undertaken using MeSH terms and the full strategy is listed in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2. These strategies was combined with the search strategy for RCTs as recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration (Alderson 2004).

The updated database search was done using the original search terms in July 2009 for the period 2005 up to 2009 and including the date the search was done. The following databases were searched: Medline, EMBASE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library. AIDSearch was not searched for the updated search as it ceased publication during 2008.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Abstracts of all trials identified by electronic or bibliographic scanning were examined by two authors (EP and TY) working independently. Where necessary, the full text was obtained to determine the eligibility of studies for inclusion. Full studies were not examined in instances where both authors agreed that the study was not a RCT.

Data extraction and management

Data from eligible trials was extracted and coded by two independent authors (EP and TY) using a standardised data extraction form. Where there were differences they were resolved by the review mentor, Nandi Siegfried. The following information was collected for each trial: type and dose of intervention used; duration of treatment; patient characteristics, including number of patients, gender, age, and co‐morbid conditions; adverse events and length of trial follow‐up. Also noted were the various diagnostic criteria used for the identification of lesions, these included presumptive as well as definitive criteria (Williams 1993). Where necessary authors were contacted for additional information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

EP and TY independently examined the components of each included trial for risk of bias using a standard form. This included information on the sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, personnel and outcome assessor), and incomplete outcome data. We did not assess selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. The methodological components of the trials were assessed and classified as adequate, inadequate or unclear as per Chapter 8 the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). Where differences arose, these were resolved by discussions with the mentor for the review.

Sequence generation

Adequate: investigators described a random component in the sequence generation process such as the use of random number table, coin tossing, cards or envelops shuffling etc.

Inadequate: investigators described a non‐random component in the sequence generation process such as the use of odd or even date of birth, algorithm based on the day/date of birth, hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgment of the sequence generation process.

Allocation concealment

Adequate: participants and the investigators enrolling participants cannot foresee assignment, e.g. central allocation; or sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

Inadequate: participants and investigators enrolling participants can foresee upcoming assignment, e.g. an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); or envelopes were unsealed or nonopaque or not sequentially numbered.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgment of the allocation concealment or the method not.

Described.

Blinding

Adequate: blinding of the participants, key study personnel and outcome assessor, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. Or lack of blinding unlikely to introduce bias. No blinding in the situation where non‐blinding is not likely to introduce bias.

Inadequate: no blinding, incomplete blinding and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgment of adequacy or otherwise of the blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Adequate: no missing outcome data, reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome,or missing outcome data balanced in number across groups.

Inadequate: reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in number across groups or reasons for missing data.

Unclear: insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions.

Unit of analysis issues

Data analysis was conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.0.24 (2010).

The weighted mean difference was calculated for continuous outcomes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For dichotomous / binary outcomes, the relative risk was calculated with 95% CIs and for time to event data the median survival time, hazard ratios and 95% CI were included.

Where trials were similar enough, we conducted a meta‐analysis. Use was made of the random effects model to calculate the overall measure of effect, as significant heterogeneity was anticipated. When trials did not allow for meta‐analysis, we reported the results reported by the investigators.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Testing for between study heterogeneity was carried out using the Chi2 and I2 provided by the RevMan software. The Chi2 test for heterogeneity was computed with a P value of 0.10 to determine statistical significance. The I2 statistic was computed to quantify inconsistency across studies. A stratified analysis of children (< 13 years) and adults was carried out. We also planned to explore any significant heterogeneity by analysis of the following subgroups:

WHO and CDC clinical disease staging (CDC 1992; WHO 1993; Table 28);

CD4 cell counts: (> 200 cells/ml; 50‐200 cells/ml; < 50 cells/ml; and

Study who were taking antiretroviral therapy or those who were not.

3. Clinical disease staging systems.

| CDC | WHO |

| A | I |

| B | II, III |

| C | IV |

However, this was not possible due to insufficient data. Instead we have reported any possible reasons for clinical heterogeneity in narrative form.

Sensitivity analysis

We were also not able to conduct a sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of the results as most comparisons included only one trial.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

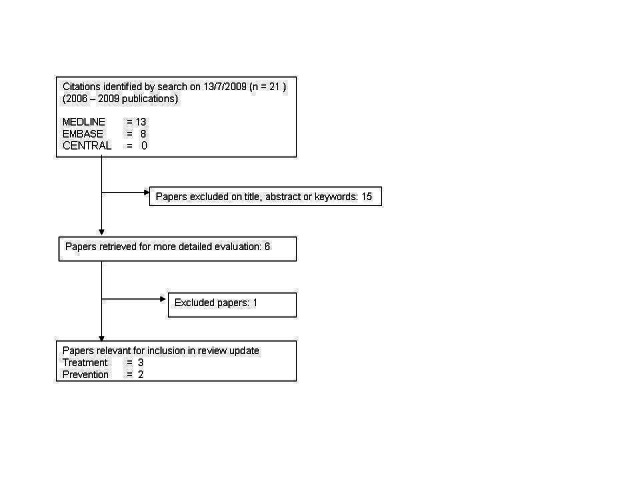

For the first publication of the review in 2006, 40 studies were retrieved. Twenty‐eight trials with a total of 3225 participants met the inclusion criteria. During the updated search for the review a further six studies were identified. Of these, five studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The review now includes 33 studies with a total of 3445 participants. The flow‐diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the retrieval and selection of studies included in the review.

1.

Flow diagram of study selection for review update

Included studies

As the review investigates both treatment and prevention of OC the review is structured to provide information for treatment and prevention separately

Treatment

Twenty‐two of the included trials looked at treatment (Arathoon 2002; Chavanet 1992; de Repentigny 1996; De Wit 1989; De Wit 1993; De Wit 1997; De Wit 1998; Graybill 1998a; Hamza 2008; Hernandez 1994; Linpiyawan 2000; Murray 1997; Nyst 1992; Phillips 1998a; Pons 1993; Pons 1997; Redding 1992; Smith 1991; Van Roey 2004; Vazquez 2002; Vazquez 2006; Wright 2009) of candidiasis. In one trial (Hernandez 1994) the participants were children aged between 7 weeks and 14 years. In three trials (Redding 1992; Smith 1991; Wright 2009) the age of the participants was not stated and in the remaining trials the participants were all adults.

Trials were conducted in different countries, in varying population groups and socioeconomic settings.

Eight of the included treatment trials were multicenter studies (de Repentigny 1996; De Wit 1997; Graybill 1998a; Hernandez 1994; Phillips 1998a; Pons 1993; Pons 1997; Vazquez 2006). Six trials were done in developing countries, namely in South Africa (Wright 2009), Tanzania (Hamza 2008), Thailand (Linpiyawan 2000; Nittayananta 2008), Uganda (Van Roey 2004), and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) (Nyst 1992). Details of geographic location and whether studies are multi or single‐centre are described in Appendix 3.

Trials used different definitions for cure, ranging from subjective clinical assessment to the use of a formal scoring system. Mycological cure was based on culture and in some instances also on microscopy. One trial (Hernandez 1994) used a composite outcome consisting of clinical cure and eradication. Colony forming units are defined as the number of colony forming units per ml of oral rinse specimen (Samaranayake 1986). Treatment trials also followed patients who were cured post treatment to determine the relapse rate. Relapse was defined as either clinical recurrence of signs and/or symptoms, or mycological relapse.

Twelve of the trials reported CD4 cell counts Arathoon 2002; Chavanet 1992; de Repentigny 1996; De Wit 1997; De Wit 1998b; Graybill 1998a; Hamza 2008; Linpiyawan 2000; Phillips 1998a; Redding 1992; Smith 1991; Van Roey 2004). None of the trials investigating the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis recorded any information regarding antiretroviral treatment or HAART received by participants.

Prevention

Eleven of the included trials investigated the prevention of OC (Goldman 2005; Just‐Nubling 1991a; Leen 1990; MacPhail 1996; Marriott 1993; McKinsey 1999; Nittayananta 2008; Pagani 2002; Revankar 1998; Schuman 1997; Stevens 1991). In two trials (Just‐Nubling 1991a; Revankar 1998 ) the age of the participants was not stated, and in the remaining trials the participants were all adults.

Trials were conducted in different countries, in varying population groups and socioeconomic settings.

Two of the included prevention trials were multicenter studies (Goldman 2005; Schuman 1997). One trial was done in a developing country (Thailand Nittayananta 2008). Details of geographic location and whether studies are multi or single‐centre are described in Appendix 3

Eight trials reported CD4 cell counts (Goldman 2005; Just‐Nubling 1991a; MacPhail 1996; McKinsey 1999; Pagani 2002; Revankar 1998; Schuman 1997; Stevens 1991). Participants received antiretroviral treatment in two of the 11 included trials investigating prevention: in Marriott 1993 zidovudine was given to 25/44 patients in the intervention group and 18/40 in the placebo group; in Schuman 1997 antiretrovirals were given but no drugs were specified. They stated that 85% (138/162) of participants in the fluconazole group and 75% (121/161) in the placebo group received antiretrovirals.

Excluded studies

Sixteen of the identified studies (Barbaro 1995a; Barbaro 1995b; Blomgren 1998; Fichtenbaum 2000; Flynn 1995; Jandourek 1998; Lim 1991; Nebavi 1998; Moshi 1998Phillips 1996; Plettenberg 1994; Powderly 1995; Skiest 2007; Smith 2001; Soubry 1991; Uberti‐Foppa 1989) were excluded from the review. Three of these (Moshi 1998; Soubry 1991; Uberti‐Foppa 1989) were initially listed as still awaiting assessment as we tried to obtain additional information in order to assess their eligibility for inclusion. After several attempts to contact the authors failed it was decided to exclude them from the review. The reasons for exclusion of all studies are given in the table of Characteristics of excluded studies.

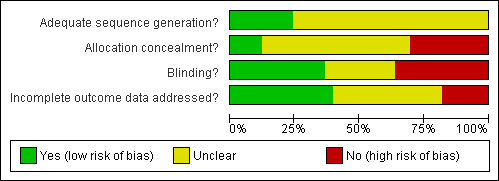

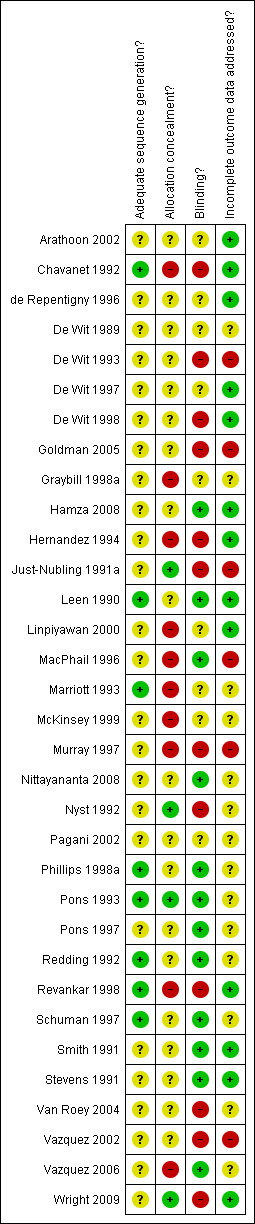

Risk of bias in included studies

When considering the risk of bias within the studies included in the review we only considered allocation, blinding and incomplete outcome data.

As with the description of the included studies the risk of bias for treatment and prevention studies are discussed separately.

The risk of bias assessment is summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Treatment

Allocation sequence generation

All trials stated that participants were randomised. One trial used a table of random numbers (Chavanet 1992) and three trials used computer generated randomisation sequences (de Repentigny 1996; Pons 1993; Redding 1992). One trial reported the use of block randomisation but did not describe how the allocation sequence was generated (Phillips 1998a ). The remainder did not describe how the allocation sequence was generated (Arathoon 2002; De Wit 1989; De Wit 1993; De Wit 1997; De Wit 1998b; Graybill 1998a; Hamza 2008; Hernandez 1994; Linpiyawan 2000; Murray 1997; Nyst 1992; Pons 1997; Smith 1991; Van Roey 2004; Vazquez 2002; Vazquez 2006; Wright 2009).

Four trials first stratified patients before randomisation into: oropharyngeal or oesophageal candidiasis (de Repentigny 1996); oropharyngeal candidiasis only or both oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis (Nyst 1992); HIV/AIDS or otherwise immunocompromised (Murray 1997); and AIDS‐related complex, or AIDS, or AIDS and esophageal candidiasis (Smith 1991).

Allocation concealment Allocation concealment was adequate in six trials (Chavanet 1992; De Wit 1997; Hamza 2008; Nyst 1992; Smith 1991; Wright 2009), inadequate in two (Graybill 1998a; Hernandez 1994) and unclear in the remaining trials.

Prevention

Allocation sequence generation

All trials stated that participants were randomised. Two trials used computer generated randomisation sequences Leen 1990; Marriott 1993). Two trials reported the use of block randomisation but did not describe how the allocation sequences were generated (Revankar 1998; Schuman 1997). The remainder did not describe how the allocation sequence was generated (Goldman 2005; Just‐Nubling 1991a; MacPhail 1996; McKinsey 1999; Nittayananta 2008; Pagani 2002; Stevens 1991).

Two trials first stratified patients before randomisation into: history of oropharyngeal candidiasis or no history of oropharyngeal candidiasis (MacPhail 1996) and CD4 count (≤ 50 vs > 50) and number of previous oropharyngeal episodes (< 2 vs ≥ 2) (Pagani 2002).

Allocation concealment Allocation concealment was adequate in one trial (Just‐Nubling 1991a), inadequate in one (Revankar 1998) and unclear in the remaining nine trials.

Blinding

Treatment

Six trials reported using double blinding (Arathoon 2002; de Repentigny 1996; De Wit 1989; De Wit 1997; Hamza 2008; Smith 1991). Placebos were used in all of these trials but did not state explicitly at which other point blinding occurred. Only providers were blinded in three trials (Pons 1993; Pons 1997; Redding 1992), and in four trials only the investigator party was blind (Graybill 1998a; Linpiyawan 2000; Murray 1997; Vazquez 2006). Both the participant and investigator were blinded in one trial(Phillips 1998a). In the rest no blinding was reportedly used (Chavanet 1992; De Wit 1993; De Wit 1998b; Hernandez 1994; Nyst 1992; Van Roey 2004; Vazquez 2002; Wright 2009).

Prevention

Patients, providers and investigators were blinded in one trial, Stevens 1991. Five trials reported using double blinding (Leen 1990; Marriott 1993; McKinsey 1999; Nittayananta 2008; Pagani 2002). Placebos were used in all of these trials but did not state explicitly at which other point blinding occurred. Both the participant and investigator were blinded in two trials (MacPhail 1996; Schuman 1997). In the rest of the trials no blinding was reportedly used (Goldman 2005; Just‐Nubling 1991a; Revankar 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

Treatment

Loss to follow‐up In 14 trials loss to follow‐up was less than 20%. In five trials (de Repentigny 1996; Graybill 1998a; Nyst 1992; Phillips 1998a; Smith 1991) loss to follow‐up was greater than 20%. Loss to follow‐up was unclear or not reported in three trials (Arathoon 2002; Murray 1997; Vazquez 2006).

Intention to Treat Analysis In six of the included studies it is indicated that intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was done (Hamza 2008; Linpiyawan 2000; Pons 1993; Redding 1992; Vazquez 2006; Wright 2009). In two trials (Vazquez 2002; Vazquez 2006) the authors reported conducting a 'modified ITT' in that all randomised participants who received at least one dose of the study medication were included in the analysis. Fifteen trials did not include ITT (Arathoon 2002; Chavanet 1992; de Repentigny 1996; De Wit 1989; De Wit 1993; De Wit 1997; De Wit 1998; Graybill 1998a; Hernandez 1994; Murray 1997; Nyst 1992; Phillips 1998a; Pons 1997; Smith 1991; Smith 1991).

Prevention

Loss to follow‐up In five trials loss to follow‐up was less than 20%. In three trials (Goldman 2005; Marriott 1993; Stevens 1991) loss to follow‐up was greater than 20%. Loss to follow‐up was unclear or not reported in three trials (McKinsey 1999; Revankar 1998; Schuman 1997).

Intention to Treat Analysis In four of the included studies, it is indicated that intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was done (Leen 1990; Marriott 1993; McKinsey 1999; Stevens 1991). Six trials did not include ITT (Goldman 2005; Just‐Nubling 1991a; MacPhail 1996; Nittayananta 2008; Pagani 2002;Revankar 1998). In one trial (Schuman 1997) it was not possible to determine whether or not they used ITT.

Effects of interventions

Treatment Twenty‐two of the included trials looked at treatment. Treatment success was assessed in the majority of trials by looking at both clinical and mycological cure. The number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated for those comparisons where the overall estimate of effect was statistically significant.

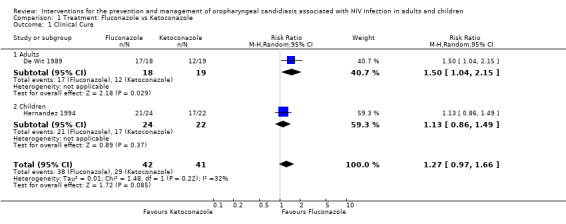

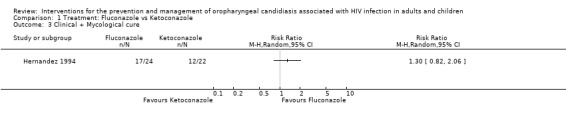

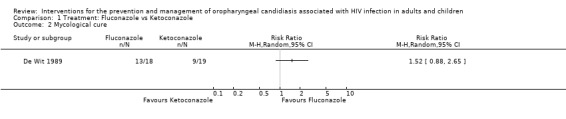

1) Fluconazole versus Ketoconazole Two trials, one in adults (De Wit 1989) (N = 37) and one in children (Hernandez 1994) (N = 46), compared oral fluconazole and ketoconazole. In the trial in adults, fluconazole was more effective than ketoconazole and favoured clinical cure (RR 1.50; 95% CI 1.04 to 2.15). This was, however, not the case in the study in children (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.49) (Analysis 1.1). From the combined result for adults and children there was no significant difference between fluconazole and ketoconazole (RR 1.27; 95 %CI 0.97 to 1.66), and there was no significant heterogeneity (I2 32.4%; Chi2 1.48 with P = 0.22). Amongst adults (De Wit 1989) there was no significant differences in mycological cure. The trial in children did not give the results for mycological cure separately, but combined with clinical cure and that was also not significantly different between fluconazole and ketoconazole (Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Ketoconazole, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Ketoconazole, Outcome 3 Clinical + Mycological cure.

Mycologically confirmed relapses were more likely in patients receiving fluconazole. De Wit 1989 followed 13 of the 18 patients assigned to fluconazole, for one month post‐treatment during which time there were six relapses (46%) after a mean of 18 days (range 10 to 24 days) with fluconazole (18 randomised, and four lost to follow‐up) and, while there was one relapse in the ketoconazole group (19 randomised, 12 cured and three lost to follow‐up) 13 days after the end of treatment.

Gastrointestinal tract toxicity (GIT) was the main adverse effect. De Wit 1989 reported severe nausea in one fluconazole patient. Diarrhoea and abdominal pain occurred in one ketoconazole patient (Hernandez 1994), and an increase in the liver enzymes (ALT and AST) occurred more often in the ketoconazole group and is reported as being mild transitory laboratory abnormalities. One patient in the fluconazole group also had thrombocytopaenia (Hernandez 1994).

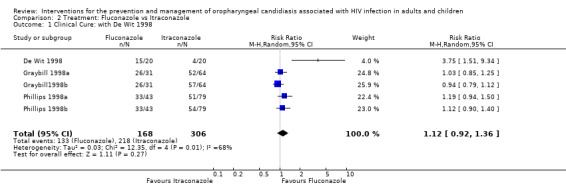

2) Fluconazole vs Itraconazole Three trials (N = 474) compared fluconazole with itraconazole (De Wit 1998; Graybill 1998a; Phillips 1998a). Graybill 1998a and Phillips 1998a both had three arms, one fluconazole and two itraconazole. In Graybill 1998a the itraconazole doses in the different arms were 200 mg per day for seven days and 200 mg per day for 14 days, in Phillips 1998a the doses in the two itraconazole arms were 100 mg per day for seven days and 14 days respectively. In order to include both itraconazole arms in the meta‐analysis the number of participants in the fluconazole arm was divided in two (Ramsay 2003). The combined RR for clinical cure was 1.12 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.36) with significant heterogeneity (I2 67.6%; Chi2 12.35 with P = 0.01) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Itraconazole, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure: with De Wit 1998.

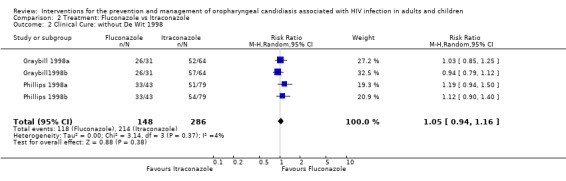

Because De Wit 1998 (RR 3.75; 95% CI 1.51 to 9.34) was an outlier, the meta‐analysis was repeated excluding this study. The revised analysis also did not indicate a benefit of one drug over the other, RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.16) with no significant heterogeneity (I2 4.3%; Chi2 3.14 with P = 0.37) (Analysis 2.2). Exploring sources of heterogeneity, mean CD4 cell counts were similar at baseline. Graybill 1998a, itraconazole (7 days) was 134 cells/mm3 (3 to 707), itraconazole (14 days) was 134 cells/mm3 and fluconazole 162 cells/mm3 (2 to 702). Phillips 1998a: fluconazole = 136 cells/ml; itraconazole (7 days) = 151 cells/ml and itraconazole (14 days) = 160 cells/mm3. De Wit 1998 reported 38 cells/mm3 for the fluconazole arm and 22 cells/mm3 for the itraconazole arm. None of the trials reported antiretroviral usage. De Wit 1998 however used itraconazole in tablet form as opposed to the oral solution used by both Graybill 1998a and Phillips 1998a and fluconazole as a single dose compared to a 2 week course in the other two studies.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Itraconazole, Outcome 2 Clinical Cure: without De Wit 1998.

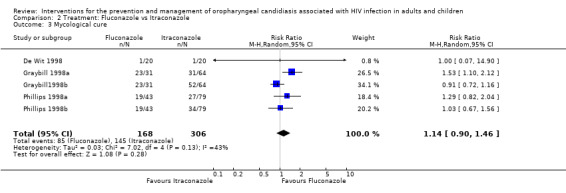

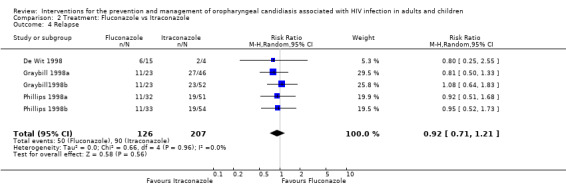

Use of fluconazole favoured mycological cure in one of the five trials. The combined RR indicated no benefit of one drug over the other (RR 1.14; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.46) with no significant heterogeneity (I2 43.0%; Chi2 7.02, P = 0.28) (Analysis 2.3). None of these showed a benefit in minimising post treatment relapse (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.21) with no heterogeneity (Chi2 0.66, P = 0.96, I2 0%) (Analysis 2.4).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Itraconazole, Outcome 3 Mycological cure.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Itraconazole, Outcome 4 Relapse.

De Wit 1998 reported that no adverse events were experienced in either group. Graybill 1998a reported that 25% of participants in each arm experienced adverse events. Nausea, diarrhoea and abdominal pain were the most common events experienced. Respiratory side effects were experienced by 21% in the fluconazole arm and 12.5% in the itraconazole arm. Phillips 1998a reported no difference in the frequency of adverse events between the three treatment groups (33% in itraconazole twice a day and 48% in the itraconazole daily group and 43% in the fluconazole group). GIT symptoms were the most frequently reported adverse event. One participant in each of the treatment groups died of causes unrelated to the study drug.

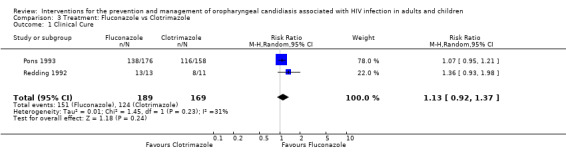

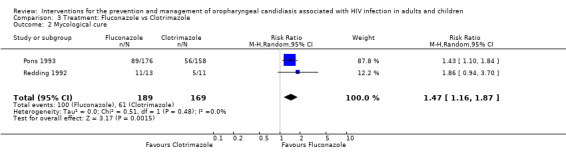

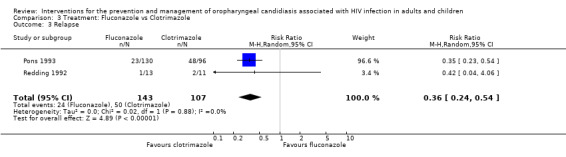

3) Fluconazole vs Clotrimazole Two trials (Pons 1993; Redding 1992) (N = 358) compared fluconazole with clotrimazole. The combined RR for clinical cure (RR 1.14; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.42) using the random effects model indicated that no treatment was superior (Analysis 3.1). Fluconazole resulted in mycological cure in Pons 1993 but not in Redding 1992. The combined RR was 1.47; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.87 with no significant heterogeneity (I2 0%; Chi2 0.51; P=0.48) (Analysis 3.2). The NNT was calculated as 6 with 95% CI 4 to 15.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Clotrimazole, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Clotrimazole, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

By day 28 post treatment 1/13 (18%) fluconazole and 2/11 (18%) clotrimazole patients relapsed (Redding 1992) compared to 23/130 (18%) fluconazole and 48/96 (50%) clotrimazole (Pons 1993), combined RR 0.36; 95% CI 0.24 to 0.54 (no significant heterogeneity). While by day 42, four out of 13 (31%) fluconazole and five out of 11(45%) clotrimazole patients relapsed (Redding 1992) and 34/99 (34%) fluconazole patients and 23/58 (40%) clotrimazole patients relapsed (Pons 1993).

The reported adverse events were similar across both arms in Pons 1993 (18% in fluconazole vs 19% in clotrimazole) with GIT the most common. Less common events included headache, dizziness, pruritis, rash, sweating and dry mouth as well as liver function abnormalities. In the majority of cases the side‐effects were mild to moderate in severity. Two participants in the fluconazole and seven in the clotrimazole arms were withdrawn from the study because of non‐life threatening treatment adverse events. Redding 1992 reported that adverse events were infrequent in both treatment groups. No patients were withdrawn from therapy because of adverse events.

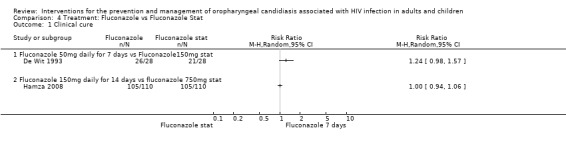

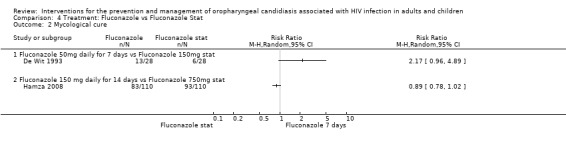

4) Fluconazole vs Fluconazole Two trials, De Wit 1993 (N = 56) and Hamza 2008 (n=220) compared different dosages of fluconazole. In De Wit 1993 one arm was 50 mg per day for 7 days and the other arm was 150 mg as a single dose. Hamza 2008 compared 150 mg per day for 14 days 750 mg as a single dose. The two studies were analysed as subgroups because of the difference in dosage as well as duration of treatment.

Clinical cure was not significantly different (Analysis 4.1). There was also no clear superiority between the dosages for mycological cure of OC (Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Fluconazole Stat, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Fluconazole Stat, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

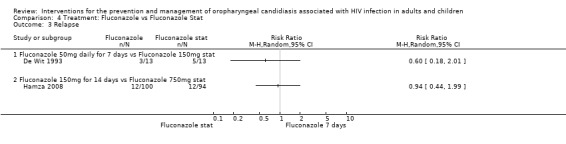

In the De Wit 1993 study 26 patients were followed for two weeks after treatment (13 per treatment group). The relapse rates within the two treatment groups are compared in Analysis 4.3 and were not significantly different. Hamza 2008 followed 194 patients for 42 days after the commencement of treatment and reported 12 relapses out of 100 patients in the 150mg fluconazole arm and 12 out of 94 patients in the fluconazole stat arm.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Fluconazole Stat, Outcome 3 Relapse.

Hamza 2008 reported the following adverse events: 14 day fluconazole: 6 patients reported gastrointestinal problems and for the single‐dose fluconazole: 6 nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and/or diarrhoea; 1 headache; 1 heart palpitations and dizziness.

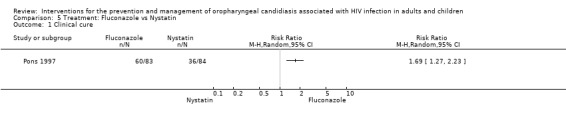

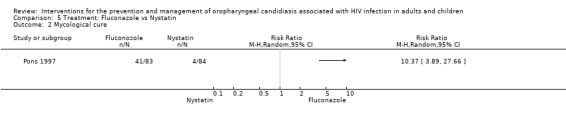

5) Fluconazole vs Nystatin One trial, Pons 1997 (N = 167) compared fluconazole with nystatin. Fluconazole favoured clinical cure, (RR 1.69; 95% CI 1.27 to 2.23) and mycological cure, (RR 10.37; 95% CI 3.89 to 27.66). For the outcome clinical cure, the NNT was calculated as 3 with 95%CI 2 to 7, and for mycological cure the NNT was 2 with 95%CI 2 to 3 (Analysis 5.1 and Analysis 5.2). GIT adverse events were the most common. One participant in each treatment group withdrew due to either nausea or vomiting. Liver enzymes were elevated in two participants in the fluconazole group. A sample of 13 participants per group was followed up for 2 weeks, 5/13 (38%) in the fluconazole stat group and 3/13 (23%) in the daily fluconazole group relapsed.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Nystatin, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Treatment: Fluconazole vs Nystatin, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

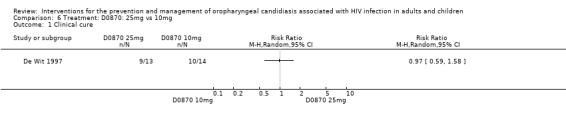

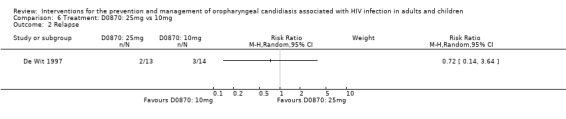

6) D0870: 25 mg vs 10 mg One trial, De Wit 1997 (N = 27) compared different dosages of D0870, a new tri‐azole antifungal agent (Cartledge 1998, Yamada 1993). Neither dosage offered an advantages over the other in bringing about clinical cure, RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.58 (Analysis 6.1). Mean CD4 counts were different, however the reported ranges overlapped (100 mg D0870 = 48 cells/mm3; range 2 to 230 and 10 mg D0870 = 100 cells/mm3; range 2 to 355). By day 14 post treatment 2/13 (15%) of the 25 mg group and 3/14 (21%) of the other group relapsed (Analysis 6.2).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Treatment: D0870: 25mg vs 10mg, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Treatment: D0870: 25mg vs 10mg, Outcome 2 Relapse.

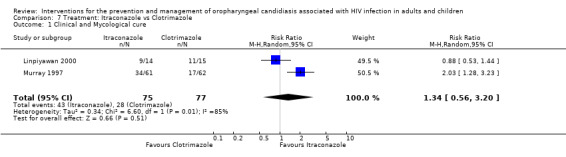

7) Itraconazole vs Clotrimazole Two trials (Linpiyawan 2000; Murray 1997) (N =152), compared itraconazole with clotrimazole. In Murray 1997 162 patients were enrolled. Of these, 123 were HIV+, 26 HIV‐ and the HIV status of the remaining 13 was unknown. For the purpose of this review, it was decided to use the 123 as the denominator. Itraconazole significantly favoured clinical cure in the Murray 1997 trial with the RR 2.03. Analysis 7.1: The combined RR 1.34; 95% CI 0.56 to 3.2, with significant heterogeneity (I2 84.9%; Chi2 6.60; P=0.01). The source of heterogeneity is unclear. Both trials used the same drug preparations and had similar participant profiles.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Treatment: Itraconazole vs Clotrimazole, Outcome 1 Clinical and Mycological cure.

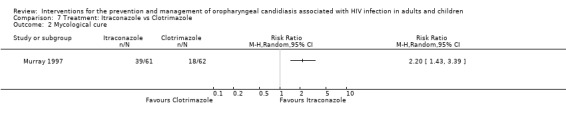

Only Murray 1997 reported on mycological cure as an outcome. Itraconazole favoured mycological cure (RR 2.20; 95% CI 1.43 to 3.39). Analysis 7.2: The NNT was calculated as 3 with 95% CI 2 to 5. One month post treatment, 46% of the itraconazole and 60% of the clotrimazole patients relapsed (Murray 1997). The median time to relapse was 31 days for itraconazole and 28 days for clotrimazole. In Linpiyawan 2000 3/9 (33%) patients in the itraconazole group and 5/5 (100%) patients in the clotrimazole group relapsed by week 4.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Treatment: Itraconazole vs Clotrimazole, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

In both studies, more participants receiving itraconazole developed GIT side effects. Two patients had transient elevation of liver enzymes (Linpiyawan 2000). Seven patients in the itraconazole group and three in the clotrimazole group had to discontinue participation prematurely as a result of adverse events (Murray 1997).

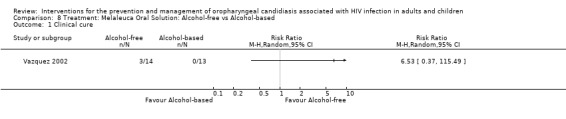

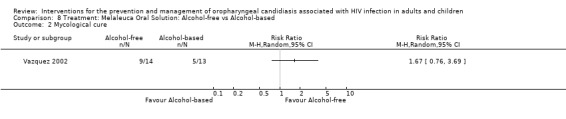

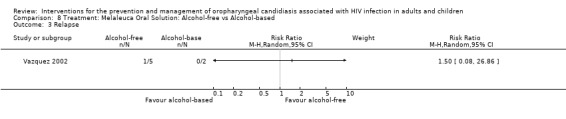

8) Melaleuca oral solution: alcohol free vs alcohol‐based One trial, Vazquez 2002 (N =27) compared an alcohol free melaleuca solution, also known as tea tree oil (Vazquez 2000), with an alcohol‐based solution of the same compound. Neither of the formulations offered any advantages in bringing about clinical cure (Analysis 8.1), mycological cure (Analysis 8.2) or preventing relapse (Analysis 8.3). By week four post treatment 0/2 (0%) alcohol‐free and 1/5 (20%) alcohol‐based patients had relapsed.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Treatment: Melaleuca Oral Solution: Alcohol‐free vs Alcohol‐based, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Treatment: Melaleuca Oral Solution: Alcohol‐free vs Alcohol‐based, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Treatment: Melaleuca Oral Solution: Alcohol‐free vs Alcohol‐based, Outcome 3 Relapse.

Oral burning was experienced in eight participants receiving alcohol‐based solution and two receiving the alcohol‐free solution.

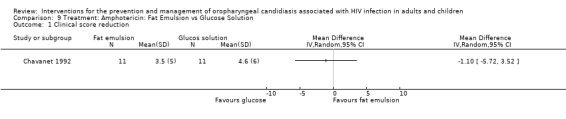

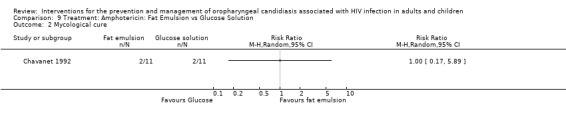

9) Amphotericin: Fat emulsion vs Glucose solution One trial, Chavanet 1992 (N =22) compared amphotericin in a fat emulsion with amphotericin glucose solution. The mean CD4 cell count for the glucose‐based solution group was 121 cells/mm3 and for the fat‐emulsion group it was 48 cells/mm3. Clinical cure was not significantly different between the two formulations (Analysis 9.1). Neither formulation provided any effect towards mycological cure (RR 1.0; 95%;CI 0.17 to 5.89) (Analysis 9.2).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Treatment: Amphotericin: Fat Emulsion vs Glucose Solution, Outcome 1 Clinical score reduction.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Treatment: Amphotericin: Fat Emulsion vs Glucose Solution, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

More frequent adverse events were experienced with the glucose preparation. Chills and fever were the most frequent side effects (66% vs 4%). Sweating and nausea were slightly less frequent in the fat emulsion group.

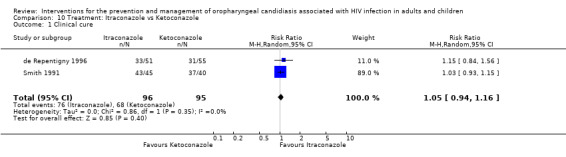

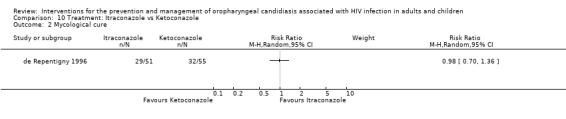

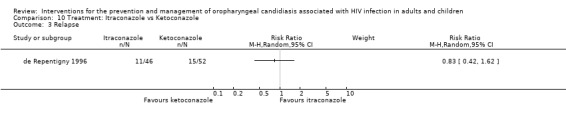

10) Itraconazole vs Ketoconazole Two trials (de Repentigny 1996, Smith 1991) (N =217) compared itraconazole with ketoconazole. The combined RR did not indicate the superiority of either treatment (Analysis 10.1). The mean days to clinical response was 32.4 ± 2.9 (95% CI 26.6 to 38.1) for itraconazole vs 28.9 ± 3.3 (95% CI 22.5 to 35.3) for ketoconazole (de Repentigny 1996). Mycological cure (de Repentigny 1996) was not favoured by either (RR 0.98; 95%CI 0.7 to 1.36) (Analysis 10.2). Within 21 days after treatment, 11/46 (24%) itraconazole and 15/52 (29%) ketoconazole patients relapsed (de Repentigny 1996). For Smith 1991 the relapse rate was > 80% in both arms within 3 months (Analysis 10.3).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Treatment: Itraconazole vs Ketoconazole, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Treatment: Itraconazole vs Ketoconazole, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Treatment: Itraconazole vs Ketoconazole, Outcome 3 Relapse.

While de Repentigny 1996 reported no significant differences in adverse event rate between the treatment groups, Smith 1991 reported that five patients had to stop ketoconazole due to serious toxic events (2 nausea, 2 hepatotoxicity and 1 generalised erythematous rash). One patient receiving itraconazole developed a maculopapular rash.

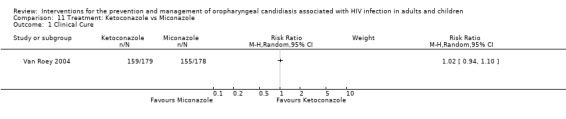

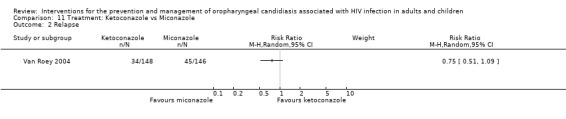

11)Ketoconazole vs Miconazole One trial, Van Roey 2004 (N = 357) compared ketoconazole with miconazole. The mean CD4 cell counts were similar with miconazole (102.3 ± 14.5 cells/mm3) and ketoconazole (109.5 ± 12.88 cells/mm3). Neither intervention clearly favoured clinical cure (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.10). Of the ketoconazole patients 34/148 (23%) and 45/146 (31%) miconazole patients relapsed (RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.51 to 1.09). Fewer drug related adverse events were noted in the miconazole group.

Gentian Violet vs Ketoconazole vs Nystatin One trial, Nyst 1992, (N = 141), consisted of three intervention arms. Gentian violet (N = 49), ketoconazole (N = 45) and nystatin (N = 47). This trial was analysed in three separate comparisons as outlined below in comparisons 12 to 14. Two patients receiving gentian violet developed irritation and small superficial ulcers of the oral mucosa 24 hours after the start of therapy.

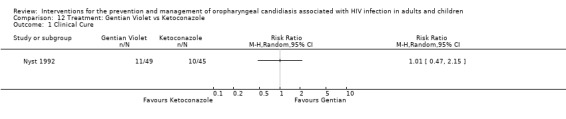

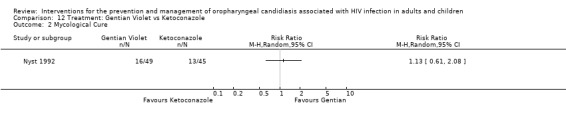

12) Gentian Violet vs Ketoconazole When comparing gentian violet with ketoconazole, clinical cure (Analysis 12.1) and mycological cure (Analysis 12.2) was not significantly different.

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Treatment: Gentian Violet vs Ketoconazole, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Treatment: Gentian Violet vs Ketoconazole, Outcome 2 Mycological Cure.

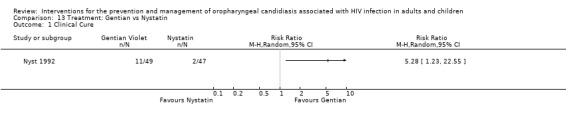

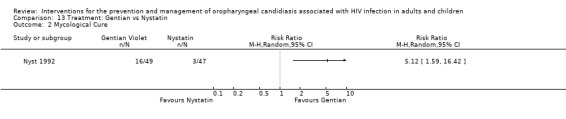

13) Gentian Violet vs Nystatin When comparing gentian violet with nystatin, gentian violet favoured clinical cure (RR 5.28; 95% CI 1.23 to 22.55) (Analysis 13.1). Gentian violet favoured mycological cure (RR 5.12; 95% CI 1.59 to 16.42) (Analysis 13.2). The NNT was calculated as 6 with 95% CI 3 to 20 for clinical cure and as 4 with 95% CI 2 to 9 for mycological cure.

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Treatment: Gentian vs Nystatin, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure.

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Treatment: Gentian vs Nystatin, Outcome 2 Mycological Cure.

14) Ketoconazole vs Nystatin In the comparison of ketoconazole with nystatin, ketoconazole favoured clinical cure with RR 5.22 95% CI 1.21 to 22.53 (Analysis 14.1). Ketoconazole favoured mycological cure (RR 4.53; 95% CI 1.38 to 14.83) (Analysis 14.2). The NNT was calculated as 6 with 95% CI 3 to 23 for clinical cure and as 4 with 95% CI 3 to 13 for mycological cure.

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Treatment: Ketoconazole vs Nystatin, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Treatment: Ketoconazole vs Nystatin, Outcome 2 Mycological Cure.

15) Caspofungin vs Amphotericin B One trial, Arathoon 2002 (N = 52), compared intravenous caspofungin with intravenous amphotericin B. Compared to other treatment options for OC, these two interventions are very expensive (Klotz 2006). Neither treatment showed any superiority, see Analysis 15.1. Mycological cure was reported as more than 75% in each of the treatment arms. Relapse during the month following discontinuation of treatment was as high as 37% and was similar among the treatment groups. Significantly fewer patients receiving caspofungin developed drug‐related fever, chills, nausea or vomiting. The incidence of local reactions (infusion related) ranged from 6 ‐ 14% across treatment arms. Drug‐related laboratory abnormalities (raised ALT, AST, ALP, creatinine and decreased potassium) were more common in patients receiving amphotericin B (Analysis 15.1).

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Treatment: Caspofungin vs Amphotericin B, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure.

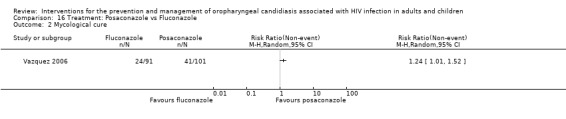

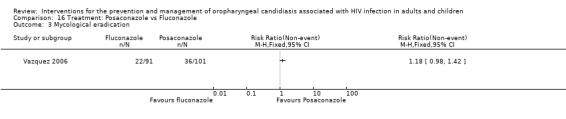

16) Posaconazole vs Fluconazole One trial, Vazquez 2006 (N=366), compared posaconazole with fluconazole. Clinical cure was not significantly different (RR 1.32; 95% CI 0.36 to 4.83). Mycological cure was significantly higher with posaconazole (RR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.52), whereas the results for mycological eradication were not statistically significant (RR 1.18; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.42).

Analysis 16.1; Analysis 16.2; Analysis 16.3

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Treatment: Posaconazole vs Fluconazole, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

16.2. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Treatment: Posaconazole vs Fluconazole, Outcome 2 Mycological cure.

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Treatment: Posaconazole vs Fluconazole, Outcome 3 Mycological eradication.

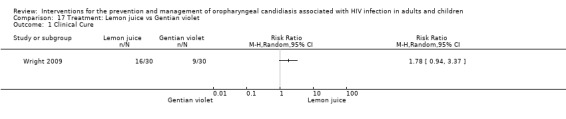

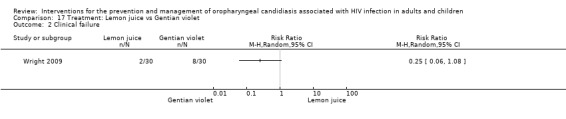

Lemon juice vs Lemon Grass vs Gentian Violet One trial, Wright 2009 (N = 90), consisted of three intervention arms. Lemon juice (N = 30), lemon grass (N = 30) and gentian violet (N = 30). This trial was analysed in three separate comparisons as outlined below in comparisons 17 to 19. The adverse events reported for the gentian violet group were purple discolouration, cracked lips and dry mouth. In the lemon juice group, the events were reported as changed taste in the mouth, and for the lemon grass group only one adverse event was reported namely increased appetite.

17) Lemon Juice vs Gentian Violet When comparing lemon juice with gentian violet, clinical cure was not significantly different (RR 1.78; 95% CI 0.94 to 3.37) (Analysis 17.1). Clinical failure was more likely in the gentian violet group than the lemon juice group (RR 0.25; 95% CI 0.06 to 1.08) (Analysis 17.2) but not statistically significant. .

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Treatment: Lemon juice vs Gentian violet, Outcome 1 Clinical Cure.

17.2. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Treatment: Lemon juice vs Gentian violet, Outcome 2 Clinical failure.

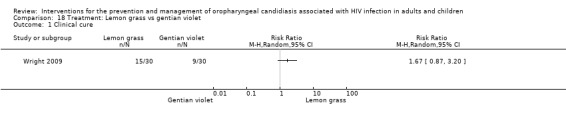

18) Lemon Grass vs Gentian Violet When comparing lemon grass with gentian violet, clinical cure was not significantly different (RR 1.67; 95% CI 0.87 to 3.20) (Analysis 18.1). Clinical failure was more likely in the gentian violet group (RR 0.25; 95% CI 0.06 to 1.08) (Analysis 18.2) but not statistically significant.

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Treatment: Lemon grass vs gentian violet, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

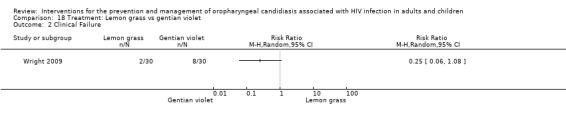

18.2. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Treatment: Lemon grass vs gentian violet, Outcome 2 Clinical Failure.

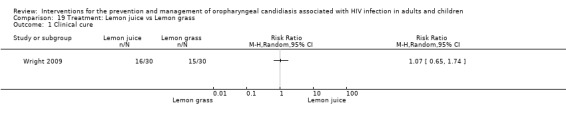

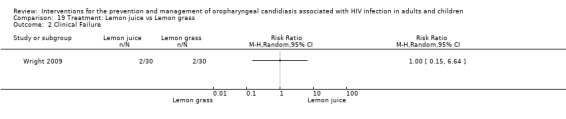

19) Lemon juice vs Lemon grass In the comparison of lemon juice with lemon grass, there was no difference between the two groups relating to clinical cure (Analysis 19.1). When looking at clinical failure there was also no difference between the two groups (Analysis 19.2).

19.1. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Treatment: Lemon juice vs Lemon grass, Outcome 1 Clinical cure.

19.2. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Treatment: Lemon juice vs Lemon grass, Outcome 2 Clinical Failure.

Prevention

Eleven RCTs looked at prevention. Successful prevention was defined as the prevention of a relapse (a reduction in the number of clinical episodes) occurring while receiving prophylaxis.

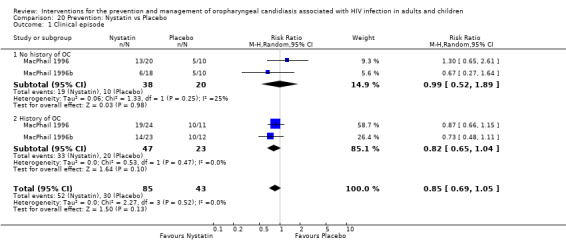

1) Nystatin vs Placebo One trial, MacPhail 1996 (N = 128), compared different dosages of Nystatin (Two nystatin pastilles of 200 000 U and one Nystatin pastilles of 200 000 U) with placebo. The participants were stratified into a group with no previous history of OC (median CD4 330 cells/mm3 (range 3 to 752)) and those with a history of OC (median CD4 166 cells/ mm3 (range 2 to 888)) with each strata having three arms. Comparing Nystatin with placebo there was no significant difference (combined RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.05) (Analysis 20.1). When comparing the two different dosages, thus excluding the placebo arms (N = 43), the prevention of clinical episodes was favoured by 2 Nystatin pastilles of 200 000 U in both strata (combined RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.50 to 0.99) (Analysis 21.1).

20.1. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Prevention: Nystatin vs Placebo, Outcome 1 Clinical episode.

21.1. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Prevention: Nystatin vs Nystatin, Outcome 1 Clinical episode.

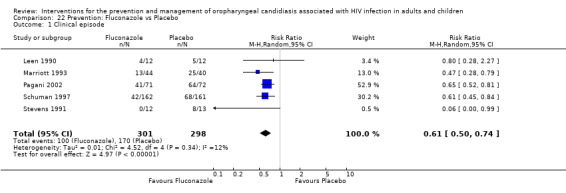

2) Fluconazole vs Placebo Five trials, Leen 1990; Stevens 1991; Marriott 1993; Pagani 2002; Schuman 1997, (N = 599) compared fluconazole with placebo. The prevention of clinical episodes was favoured by fluconazole (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.50 to 0.74), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 11.5%; Chi2 4.52, P = 0.34) see Analysis 22.1. The NNT was calculated as 4 with 95% CI 3 to 6.

22.1. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Prevention: Fluconazole vs Placebo, Outcome 1 Clinical episode.

In Marriott 1993 mycologically confirmed relapse occurred in 12/25 (48%) fluconazole and 17/18 (94%) placebo patients. In Schuman 1997 clinical resistance developed in six fluconazole and seven placebo patients. Pagani 2002 reported the number of relapses per patient as well as the time to relapse (median time to first relapse was 175 days for fluconazole vs 35 days for placebo). Clinical resistance observed in five patients was associated with isolation of a C. albicans strain resistant to fluconazole. This was observed during the study in two patients in the fluconazole group and one in the placebo group, and also within one month of the study end in two patients in the fluconazole group. These patients had a cumulative dose of fluconazole before study entry of a mean value of 8.7 g compared with 2.9 g in patients without clinical failure.

In Marriott 1993 zidovudine was given to 25 out of 44 patients in the treatment group and 18 out of 40 in the placebo group. Schuman 1997 reported that antiretrovirals were given but does not indicate which drug was given. They state that 85% (138/162) participants in the fluconazole group and 75% (121/161) in the placebo group received antiretrovirals.

Leen 1990 reported that diarrhoea developed in one patient shortly after receiving fluconazole. Marriott 1993 reported that in the fluconazole group 40 intercurrent illnesses, nine adverse drug reactions and three deaths occurred, and in the placebo group there were five intercurrent illnesses, one adverse drug reaction and two deaths. Stevens 1991 reported no differences between the two groups with regard to adverse events.

Leen 1990 did not report on CD4 cell count, Stevens 1991 reported that 11 patients had a CD4 cell count of less than 200 cells/mm3 and in Marriott 1993 the median for the fluconazole group was 18 cells/mm3 with a range of 0 ‐ 299, and in the placebo group it was 38 cells/mm3 with a range of 0‐200. Schuman 1997 reported a median CD4 cell count of 172 cells/mm3 in the fluconazole group and 186 cells/mm3 in the placebo group. In Schuman 1997, 31% in the fluconazole group and 25 % in the placebo group had a CD4 cell count of less than 100 cells/mm3. Pagani 2002 reported no difference in CD4 cell count between the different groups within the study.

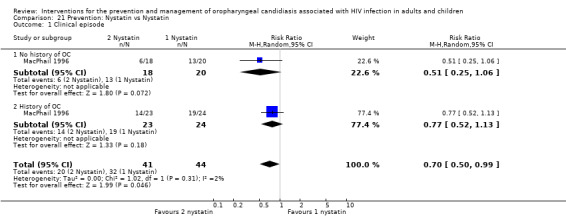

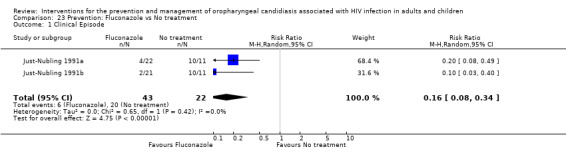

3) Fluconazole vs No treatment One trial, Just‐Nubling 1991a (N = 65) compared fluconazole with no treatment. In the fluconazole group there were two arms with different dosages, i.e. 50 mg (N = 20) and 100 mg (N = 22). In order to include both fluconazole arms in the meta‐analysis the number of participants in the no‐treatment arm was divided in two (Ramsay 2003). The prevention of clinical episodes was favoured by fluconazole in both dosage arms with RR 0.10 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.40) and 0.20 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.49) respectively. The meta‐analysis indicates that fluconazole was effective in the prevention of OC ( RR 0.16; 95%CI 0.08 to 0.34) (Analysis 23.1), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 0%; Chi2 0.65, P = 0.42). The NNT was calculated as 1 with 95%CI; 1 to 2. Just‐Nubling 1991a reported on the stage of patients disease as well as the number of relapses per patient. In the no‐treatment group 20/21 patients experienced 60 relapses, in the 50 mg fluconazole group 2/18 patients experienced 4 relapses and in the 100 mg fluconazole group 4/19 patients experienced 9 relapses. Just‐Nubling 1991a reported allergic exanthema as an adverse event in the fluconazole group. All patients had a CD4 cell count of less than 100 cells/mm3.

23.1. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Prevention: Fluconazole vs No treatment, Outcome 1 Clinical Episode.

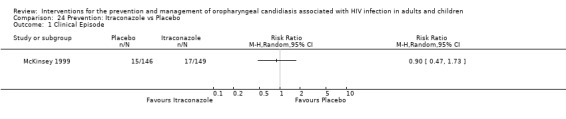

4) Itraconazole vs Placebo One trial, McKinsey 1999 (N = 298), compared itraconazole with placebo. Only data from participants who met the eligibility criteria, were enrolled and received at least one dose of the test medication were reported. They enrolled 298 patients of whom three were ruled to be ineligible, two withdrew consent before receiving the study drug and one was taking disallowed medication. It is not clear from the text whether randomisation was done before or after the exclusion of these three participants.

Itraconazole was not superior to placebo (Analysis 24.1). Diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, elevated liver enzyme levels, rash and Stevens‐Johnson syndrome were more common adverse events in the itraconazole arm of the study. The median CD4 cell count in the placebo group was 63 cells/mm3 and 57 cells/mm3 in the itraconazole group.

24.1. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Prevention: Itraconazole vs Placebo, Outcome 1 Clinical Episode.

5) Fluconazole: Intermittent vs Continuous

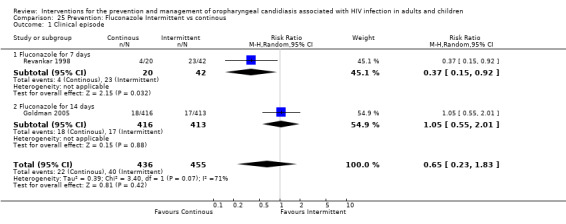

Two studies, Goldman 2005 and Revankar 1998 (N=891), compared the continuous use of fluconazole with intermittent use.

In Revankar 1998 the continuous use favoured the prevention of clinical episodes (RR 0.37; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.92). In the Goldman 2005 study there was no clear superiority between the two treatment arms (RR1.05; 95% CI 0.55 to 2.01).

The combined RR was 0.65 (95%CI 0.23 to 1.83) with significant heterogeneity (I2 71%; Chi2 3.40 with P=0.07) (Analysis 25.1). Possible sources of heterogeneity could be the difference in sample size between the studies, Goldman 2005( N=829) and Revankar 1998 (N=26), and also the difference in fluconazole dosage and length of treatment period.

25.1. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Prevention: Fluconazole Intermittent vs continous, Outcome 1 Clinical episode.

Revankar 1998 reported resistance developing amongst 13/28 (46%) patients in the intermittent group and 9/16 (56%) patients in the continuous group. In the intermittent group 23/28 (82%) patients experienced relapses vs 4/16 (25%) in the continuous group. No information was given on adverse events. The mean CD4 cell count of patients on continuous therapy was 43 ± 37 cells/mm3 with a range of 4 to 116 compared with 44 ± 51 cells/mm3 with a range of 4 to 191 in patients receiving intermittent therapy. Goldman 2005 reported a total of 14 adverse events with four in the episodic arm (n=416) and 10 in the continuous arm (n=413). The median CD4 cell count of patients on continuous therapy was 52 cells/mm3 with the range of 0‐250 compared to 50 cells /mm3 with a range of 0‐209 in patients receiving intermittent therapy.

6) Chlorhexadine vs Normal Saline

One study, Nittayananta 2008 (N=75), compared the use of chlorhexidine with normal saline to prevent relapse of OC. The study reported the number of days from when patients started using the mouth‐rinse until relapse. Time to recurrence of OC was not statistically significant. The time to recurrence counted by number of visits ranged from 1‐ 15 (median 3) in the chlorhexidine group and 1‐8 (median 2) in the normal saline group (reported p>0.05).

Discussion

As the results of the review are divided into the treatment and prevention of oro‐pharyngeal candidiasis the discussion is structured in the same format.

Treatment A number of treatment options, both topical and systemic, are available for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis. The main classes of antifungal agents used for the treatment of oral candidiasis are the polyenes (e.g. nystatin and amphotericin), imidazoles (e.g. clotrimazole) and the tri‐azoles such as fluconazole (Hunter 1998). Even though topical agents may be effective, they are very often unpalatable and their use can also be inconvenient (De Wit 1998b).

In this review, 22 trials investigating the treatment of OC met our inclusion criteria. For the outcome clinical cure, fluconazole was more effective than nystatin, had similar effects as posaconazole and had no difference in effect compared to ketoconazole, itraconazole and clotrimazole. The effect of itraconazole was the same as that of clotrimazole and ketoconazole. Gentian violet and ketoconazole had similar effects and were each better than nystatin. Ketoconazole also had the same effect as miconazole. In contrast to clinical cure, both fluconazole and itraconazole were better than clotrimazole for mycological cure, that is a negative Candida culture or negative KOH microscopic preparation.

One new study Wright 2009 compared gentian violet with lemon juice and lemon grass as treatment for the OC. There was no significant difference in effect between the three different interventions.

In a previously published review, Patton and colleagues (Patton 2001) found that the efficacy of fluconazole ranged from 87% to 100%, bringing about a complete clinical response, that is the absence of signs or symptoms of OC, or both. This is similar to what was found in this review, namely that the effectiveness of fluconazole in bringing about clinical cure of OC is the highest, followed by itraconazole. This is also similar to the findings of a trial comparing fluconazole with itraconazole for the treatment of OC in cancer patients (Oude Lashof 2004). The fact that itraconazole did not give significant results could be explained by drug interactions and also unpredictable absorption of itraconazole capsules (De Wit 1998b).

The sample size of the treatment trials ranged from 22 to 357 with ten trials having less than 100 participants. With such small sample sizes it is thus not possible to draw any real robust conclusions. Some trials had a very high loss to follow‐up creating underpowered studies. Due to the limited number of studies per comparison combined with the small sample size of the majority of studies the meta‐analysis did not assist in raising the power of the comparison to such an extent as to allow for meaningful results in most comparisons.

The trials did not always use the same outcome measures which also made it more difficult to combine the results. If trials were standardised and conformed to CONSORT (Altman 1996; Moher 1987) it would improve research, reporting and hence also clinical practice.

Five of the 22 studies investigating treatment of OC were conducted in developing countries (Hamza 2008; Linpiyawan 2000; Nyst 1992; Van Roey 2004; Wright 2009). Lack of availability and cost of some of the drugs in resource‐poor countries may limit the relevance to all settings.

In addition this review is not able to make definitive recommendations regarding the treatment of OC in HIV‐positive children as only one trial with children was found (Hernandez 1994). The sample size of the trial was also small (n=48).

Prevention Eleven trials investigated the prevention of OC in adults. As no trials investigating prevention in children was found this review is not able to make recommendations regarding OC prevention in HIV‐positive children. Compared to placebo and no treatment, fluconazole was effective in preventing clinical episodes from occurring. Revankar 1998 found that continuous fluconazole was more effective than intermittent treatment. In contrast, both nystatin and itraconazole were not effective in preventing OC. A review of studies of the use of nystatin in immunodepressed patients also found similar results (Gotzsche 2005). No trial was found that investigated the prevention of OC in children.

Only one study reported drug resistance testing for Candida species where there had been prophylactic failure (Pagani 2002). None of the studies reported on the impact of compliance with treatment on the results of studies. Compliance is important as failure of prophylaxis might be due to the patient's inability or unwillingness to adhere to the therapy rather than the true reflection of the treatment efficacy (Patton 2001).

Fluconazole, a bis‐tri‐azole antifungal agent, is not altered by gastric acidity and therefore has less risk of hepatotoxicity. There is however concern that prolonged use of fluconazole increases the risk of developing azole‐resistant Candida albicans (Martin 1999; Patton 2001). When the decision has to be made whether to provide prophylaxis for OC it is necessary to weigh the risks and cost against the benefits. In patients who are HIV positive, it is rare for OC to develop into possible fatal fungemia or even systemic candidiasis (Just‐Nubling 1991a) which makes waiting until the OC appears before starting treatment an alternative to prophylaxis.

Although the use of fluconazole reduces the risk of OC in patients with advanced HIV it is not recommended as primary prophylaxis because there is potential for resistant Candida organisms to develop as well as the cost of prophylaxis. For the same reasons, chronic prophylaxis is also not recommended (CDC 1999). In patients with low CD4 cell counts, the prolonged use of systemically absorbed azoles increases their risk of developing azole resistance.

The number of participants enrolled in the studies ranged from 13 to 323 with five of the nine included studies investigating prevention having less than 100 participants. Some trials had a very high loss of participants to follow‐up creating underpowered studies. Due to the limited number of studies per comparison combined with the small sample size of the majority of studies, the meta‐analysis did not assist in raising the power of the comparison to such an extent as to allow for meaningful results in most comparisons.

As in the case of the treatment trials, prevention trials did not always use the same outcome measures which made it more difficult to combine the results. Again standardisation and conforming closely to CONSORT (Altman 1996; Moher 1987) will improve research, reporting and clinical practice. None of the included studies investigating the prevention of OC were conducted in resource‐poor settings and this may limit the relevance of our results in some settings. As no trials investigating the prevention of OC in children were identified, this review is unable to come to any conclusion as to the prevention of OC in children.

HAART None of the included studies investigated the effects of HAART or any other form of antiretroviral treatment on OC treatment or prevention. The use of antiretroviral therapy in HIV infection may be associated oral lesions related to its side effects as well as reconstitution of the immune system (IRIS). While protease inhibitors have been shown to directly attenuate the adherence of Candida albicans to epithelial cells in vitro (Bektic 2001), (Cauda 1999; Cassone 1999). The impact of this intervention warrants further investigation with regard to clinical presentation and mycological effect.

Economics None of the trials provided any information on the cost‐effectiveness of either treatment or prophylaxis of OC. There is evidence that the cost‐effectiveness of prophylaxis of HIV‐related opportunistic infections varies widely, but no specifics were provided on OC (Freedberg 1998). In general, azoles are the more expensive compounds, with ketoconazole being cheaper, but with more side‐effects. One trial (Nyst 1992) reported the cost of gentian violet, nystatin and ketoconazole in Africa as this could have a major impact on the choice of treatment. Gentian violet is much cheaper at 0.5 US $/30 ml than ketoconazole (13‐17 US$/10 tablets) and nystatin oral suspension (of which 4 bottles of 2.4 million units are necessary per treatment course at 4‐5 US$/bottle).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Four new studies were added to the review, but their results does not alter the final conclusion of the review.

Due to only one study in children it is not possible to make recommendations for treatment or prevention of OC in children. Amongst adults, there were few studies per comparison. Insufficient evidence was found to come to any conclusion about the effectiveness of clotrimazole, nystatin, amphotericin B, itraconazole or ketoconazole with regard to OC prophylaxis. The direction of findings suggests that ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole and clotrimazole improved the treatment outcomes. In comparison to placebo, fluconazole is an effective preventative intervention. However, the potential for resistant Candida organisms to develop as well as the cost of prophylaxis might impact on the feasibility of implementation. No studies were found comparing fluconazole with other interventions.

Implications for research.

It is encouraging that low‐cost alternatives are being tested, but more research needs to be on in this area and interventions like gentian violet and other less expensive anti‐fungal drugs to treat OC to be evaluated in larger studies. More well designed treatment trials with larger sample size are needed to allow for sufficient power to detect differences in not only clinical, but also mycological response and relapse rates. There is also a strong need for more research to be done on the treatment and prevention of OC in children as it is reported that OC is the most frequent fungal infection in children and adolescents who are HIV positive. More research on the effectiveness of less expensive interventions also needs to be done in resource‐poor settings. Currently few trials report outcomes related to quality of life, impact on daily activities, nutrition, or survival. Future researchers should consider measuring these when planning trials. Development of resistance remains under‐studied and more work must be done in this area. Oral lesions associated with HIV form part of the clinical spectrum of immune reconstitution associated with ARV use. More stringent criteria needs to be applied to studies in order to elucidate the true effect of OC treatment medication in persons using ARV therapy. It is recommended that trials be more standardised and conform more closely to CONSORT.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 October 2010 | New search has been performed | New studies added, review updated. Conclusions unchanged. |

| 5 October 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New studies added and review has been updated. Conclusions have not changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2002 Review first published: Issue 3, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 February 2010 | New search has been performed | The literature search was updated to July 2009, Five new studies Goldman 2005, Hamza 2008, Nittayananta 2008, Vazquez 2006 and Wright 2009 met inclusion criteria and were included. |

| 21 April 2008 | New search has been performed | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 January 2008 | New search has been performed | We updated our search to January 2008. We identified three additional relevant trials of which two (Goldman 2005; Vazquez 2006) met our inclusion criteria and the third, Skiest 2007, was excluded. |

| 23 May 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nandi Siegfried for her mentoring, help and advice. We also acknowledge the very valuable advice and assistance received from George Rutherford, Coordinating Editor of the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group and Gail Kennedy, Review Group Coordinator of the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group, and Peter Robinson, School of Clinical Dentistry, Sheffield, for extremely valuable input and advice on the final report of the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. PubMed Search strategy

Database: PubMed 2005 ‐ 2009

Date: 13 July 2009

| Search | Most Recent Queries | Time | Result |