Key Points

Question

What is the safety and tolerability of a chikungunya virus–like particle vaccine (CHIKV VLP) in a chikungunya endemic area?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 400 healthy adults in 6 Caribbean sites, CHIKV VLP compared with placebo did not result in a significantly increased risk of clinically important adverse events.

Meaning

In this phase 2 trial, a chikungunya virus–like particle vaccine appeared to be safe and well-tolerated, supporting a phase 3 trial.

Abstract

Importance

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a mosquito-borne Alphavirus prevalent worldwide. There are currently no licensed vaccines or therapies.

Objective

To evaluate the safety and tolerability of an investigational CHIKV virus–like particle (VLP) vaccine in endemic regions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 clinical trial to assess the vaccine VRC-CHKVLP059-00-VP (CHIKV VLP). The trial was conducted at 6 outpatient clinical research sites located in Haiti, Dominican Republic, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Puerto Rico. A total of 400 healthy adults aged 18 through 60 years were enrolled after meeting eligibility criteria. The first study enrollment occurred on November 18, 2015; the final study visit, March 6, 2018.

Interventions

Participants were randomized 1:1 to receive 2 intramuscular injections 28 days apart (20 µg, n = 201) or placebo (n = 199) and were followed up for 72 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the safety (laboratory parameters, adverse events, and CHIKV infection) and tolerability (local and systemic reactogenicity) of the vaccine, and the secondary outcome was immune response by neutralization assay 4 weeks after second vaccination.

Results

Of the 400 randomized participants (mean age, 35 years; 199 [50%] women), 393 (98%) completed the primary safety analysis. All injections were well tolerated. Of the 16 serious adverse events unrelated to the study drugs, 4 (25%) occurred among 4 patients in the vaccine group and 12 (75%) occurred among 11 patients in the placebo group. Of the 16 mild to moderate unsolicited adverse events that were potentially related to the drug, 12 (75%) occurred among 8 patients in the vaccine group and 4 (25%) occurred among 3 patients in the placebo group. All potentially related adverse events resolved without clinical sequelae. At baseline, there was no significant difference between the effective concentration (EC50)—which is the dilution of sera that inhibits 50% infection in viral neutralization assay—geometric mean titers (GMTs) of neutralizing antibodies of the vaccine group (46; 95% CI, 34-63) and the placebo group (43; 95% CI, 32-57). Eight weeks following the first administration, the EC50 GMT in the vaccine group was 2005 (95% CI, 1680-2392) vs 43 (95% CI, 32-58; P < .001) in the placebo group. Durability of the immune response was demonstrated through 72 weeks after vaccination.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among healthy adults in a chikungunya endemic population, a virus-like particle vaccine compared with placebo demonstrated safety and tolerability. Phase 3 trials are needed to assess clinical efficacy.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02562482

This clinical trial tested whether the chikungunya virus–like particle vaccince was safe for participants living in chikungunya endemic areas.

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) consists of 3 genotypes that behave as a single serotype,1 making it an ideal target for vaccine development. Global spread began in 2005, and in 2013 the virus was first identified in the Caribbean, establishing it as endemic in the region.2,3 Chikungunya virus causes substantial morbidity, so a safe and effective vaccine is needed.

Chikungunya virus is transmitted by an Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus mosquito.3 Incubation time is between 2 and 6 days, resulting in a febrile illness characterized by arthralgias, polyarthritis, and rashes.4,5 Between 30% and 50% of patients can experience debilitating arthritis and fatigue for years afterward.6 The immunologic response to CHIKV is characterized by the appearance of IgM antibodies within 2 to 5 days following infection and IgG after several weeks.7 Neutralizing antibodies are considered a primary correlate of protection, evidenced by survival from lethal CHIKV challenge in immunodeficient mice via passive antibody transfer.8,9

The virus-like particle (VLP), vaccine VRC-CHIKVLP059-00-VP (CHIKV VLP), was developed by the Vaccine Research Center.9 Virus-like particles mimic conformational viral epitopes but lack a viral genome and are considered highly immunogenic and safe.10,11 Several VLP vaccines are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human use including hepatitis B virus and human papillomavirus, all with highly favorable safety and efficacy profiles.

The unadjuvanted CHIKV VLP vaccine was initially evaluated in a nonhuman primate model, eliciting high-titer neutralizing antibodies that protected against heterologous challenge with viral strains not contained in the vaccine.9 In a phase 1 trial involving healthy adults, the vaccine was safe, well-tolerated, and induced neutralizing antibody responses comparable with natural infection titers and was able to neutralize all 3 CHIKV genotypes.1,12 The objective of this phase 2 clinical trial was to assess the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the CHIKV VLP vaccine in endemic regions.

Methods

Study Design

This multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial examined the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of VRC-CHKVLP059-00-VP in healthy adults at 6 endemic CHIKV sites in the Caribbean. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1, and statistical analysis plan is included in Supplement 2.

The trial was conducted at 6 outpatient clinical research sites: San Juan Hospital Research Unit, Puerto Rico; Puerto Rico Clinical and Translational Research Consortium, Puerto Rico, a unit of the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus, San Juan; the Haitian Group for the Study of Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections, Haiti; Instituto Dermatologico y Cirugia de Piel, Dominican Republic; University Hospital of Martinique, Martinique; and University Hospital of Guadeloupe, Guadeloupe.

The trial protocol was reviewed and approved by site-specific institutional review boards, adhering to country-specific requirements. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases data and safety monitoring board monitored the study at predefined intervals. The trial was conducted in accordance with clinical research regulations from the US Department of Health and Human Services and applicable international regulatory authorities. Participants were recruited using institutional review board–approved materials, as well as by word of mouth. Written informed consent was obtained from participants by study team members before participation in any study-related activities, including testing for previous CHIKV exposure. The informed consent process included review of the study procedures, risks, and benefits with the opportunity to ask questions of study team members and completion of a written or verbal Assessment of Understanding form, to assess level of comprehension of the trial.

Participants

Participants were healthy adults, aged 18 to 60 years. Eligibility was determined by 36 inclusion and exclusion criteria based on clinical laboratory results, medical history, and physical examination. Participants were required to test negative on the CHIKV IgG/IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) screening kit (InBios, International Inc) as assessed during the screening period (up to 56 days prior to randomization) and had no prior exposure to an investigational CHIKV vaccine. Additional testing was performed on the study enrollment samples collected from participants at the Dominican Republic and Haiti sites using the screening kit.

Randomization and Masking

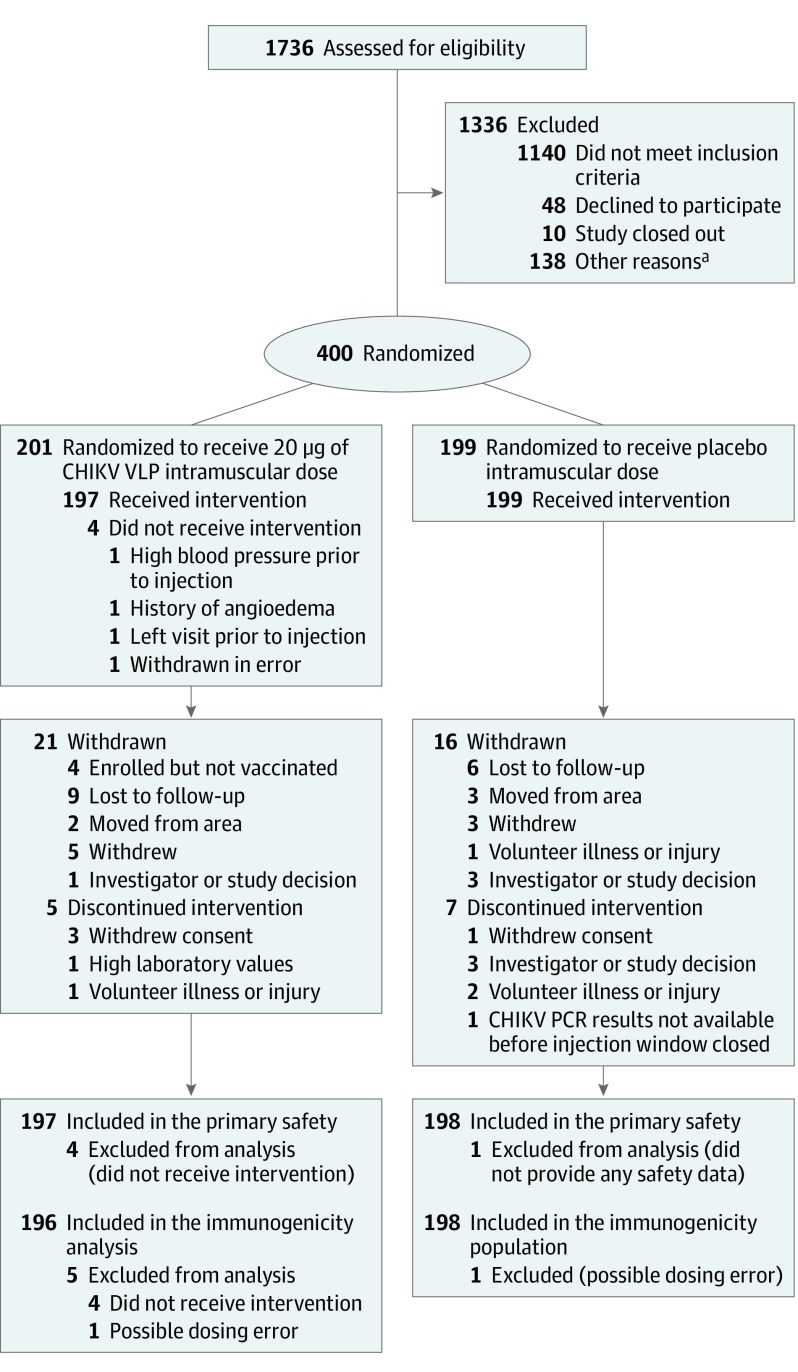

Participants were randomized to receive the vaccine or phosphate-buffered saline placebo in a 1:1 ratio using a permuted block design with a block size of 4 (Figure 1). Randomization was stratified within sites by age groups (18-40 and 41-60 years) to ensure equal age distribution between the 2 groups. Randomization occurred online using an electronic system. The protocol statistician prepared the randomization schedule. Injections were prepared by an unblinded site pharmacist or by qualified personnel who were not involved in participant assessments and did not discuss randomization assignments with the study clinicians. The participants, data entry personnel at the sites, and the laboratory personnel performing immunologic assays were blinded to the treatment assignments for all injections. Maintenance of the blind was governed by the study protocol. All participants and study team members were unblinded following completion of data collection and the locking of the trial database.

Figure 1. Recruitment, Randomization, and Follow-up of Participants in the Chikungunya Virus–Like Particle Vaccine Clinical Trial.

aOther reasons includes that participants withdrew consent, enrolled after the study stopped or was paused at the site, exceeded protocol-defined maximum of 56 days between screening and enrollment, or lost interest in participation.

Procedures

The vaccine, VRC-CHKVLP059-00-VP,12 was administered twice 28 days apart via intramuscular injection into the deltoid at a dose of 20 µg (0.5 mL). The dose was selected based on preclinical data and phase 1 clinical data showing that 3 dose levels (10 µg, 20 µg, and 40 µg) were safe and well tolerated and that elicited robust and durable titers of CHIKV neutralizing antibodies.12 Additional details on preclinical and phase 1 data along with study dose and schedule selection can be found in the trial protocol (Supplement 1).

The placebo, VRC-PBSPLA034-00-VP, was composed of sterile phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.2 and was manufactured under Good Manufacturing Practice regulations. The 0.5 mL doses were administered twice 28 days apart.

Immunogenicity

The CHIKV-specific neutralizing antibody responses were measured using the attenuated CHIKV strain 181/cone 25 in a previously described focus reduction neutralization test at baseline and at week 8 (4 weeks following the second injection) and reported as effective concentration (EC50) values.13 The EC50 is the dilution of sera that inhibits 50% infection in the viral neutralization assay. Durability of the immune response was measured in a different laboratory using a CHIKV luciferase neutralization assay through 72 weeks for vaccine recipients found to be seronegative at baseline and reported as NT80 values. NT80 is the reciprocal dilution of sera associated with an 80% reduction in viral activity (eMethods in Supplement 3). The 2 neutralization assays used, focus reduction neutralization test and CHIKV luciferase, are highly correlated (R2 = 0.94).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the safety and tolerability of VRC-CHKVLP059-00-VP in a 2-injection vaccine regimen (days 0 and 28) at a dose of 20 µg in healthy adults residing in endemic regions. Assessment of safety included clinical observation and monitoring of protocol-specified laboratory parameters (specifically, complete blood cell count and alanine aminotransferase concentrations). After each injection, local (injection site) and systemic reactogenicity symptoms were assessed with the use of a 7-day diary card and recorded into an electronic database. Laboratory measures of safety were performed through 28 days after the second injection, and all unsolicited adverse events occurring from receipt of the first study injection through 28 days after administration of second study injection were recorded. Serious adverse events, new chronic medical conditions, and chikungunya cases (Supplement 3) were recorded throughout the 72-week study. All adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms and graded for severity with a table adapted from the US FDA Guidance for Industry Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials.14

The secondary outcome was the vaccine-specific immune response by neutralizing antibody assay at week 8.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size for this study was not selected to test a formal null hypothesis. The power calculations assumed a 10% loss to follow-up in both treatment groups for the primary and secondary end points. The power to observe at least 1 safety event (adverse event or solicited reactogenicity event) in a single group of 180 participants was 83.6% when the true rate of the safety event was 1%, and 97.4% when the true safety event rate was 2%. Vaccine-specific neutralization antibodies were not anticipated in the nonvaccinated group. Therefore, direct comparison between the active and placebo group was of minimal value in assessing sample size.

Safety was analyzed in the safety population, composed of all randomized participants who received at least 1 injection and provided safety data via diary card following the injection. For the final statistical analysis, an immunogenicity population was analyzed consisting of randomized participants who received at least 1 injection with nonmissing immunogenicity data at their week 8 visit, analyzed according to the study product received. Two participants were excluded from the immunogenicity analyses due to possible dosing errors. It was determined upon unblinding and data review that the dosing errors did not occur; however, these participants were excluded because statistical analysis was already complete at the time of determination. This study was not powered to perform formal subgroup analyses. Age stratum (18-40 and 41-60 years) and site were used to define prespecified subgroup analyses for the purpose of providing sensitivity descriptive statistics for secondary immunogenicity outcomes.

The magnitude of immune response was assessed by calculating the geometric mean titer (GMT) of participant EC50 focus reduction neutralization test assay results at baseline and week 8. Any values less than the lower limit of detection (30) of the assay were imputed as 15 prior to analysis. The geometric mean ratio (GMR) was calculated as the GMT at week 8 over the GMT at baseline. Comparisons of the magnitude of immune responses were performed using 2-sided t tests on the log-transformed data. In cases of small-sample skewed subsets of data, P values from the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test were used. The frequency of immune response measured by the focus reduction neutralization test at week 8 was evaluated by tabulating the number and percentage of participants with a positive response defined as an EC50 value of 30 or higher. Uncertainty in estimates of percentages was assessed using exact (Clopper-Pearson) 95% CIs for each study group. A 2-sided Fisher exact test was used in all comparisons of frequency between groups. Durability of the immune response was assessed in vaccine recipients without neutralizing antibody titers at baseline by CHIKV luciferase neutralization assay (eMethods in Supplement 3).

Additional testing of the 168 participants enrolled in the Dominican Republic and Haiti was performed using the IgG/IgM ELISA screening kit on samples stored from the study enrollment and randomization day taken just prior to their first injection, results of which were used to define baseline seropositivity. A post hoc analysis of the magnitude of immune response by baseline seropositivity was performed by calculating the GMT with 95% CIs, GMR with 95% CIs and comparisons using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and positive response frequency with 95% CIs and comparisons using the 2-sided Fisher exact test. To compare any repeat ELISA screening assay results and baseline neutralization assay results, the Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated and used to define the direction and magnitude of the relationship between the 2 assays.

The threshold of significance was set at a P value of .05 or less, and all statistical tests were 2-sided. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Between November 18, 2015, and October 20, 2016, 1736 participants were screened for study eligibility and 400 were subsequently enrolled and randomized: 201 to receive the vaccine and 199, the placebo. The final study injection was administered on November 17, 2016, and the final study follow-up visit was March 6, 2018. The study population consisted of 199 women (50%) and 201 men (50%) with a mean age of 35 years (range, 18-60 years; Table 1). Four participants randomized to the vaccine group never received the vaccine, 5 received only 1 of the 2 planned vaccinations, 192 received both vaccinations, and 180 completed the study. Seven patients randomized to the placebo group received 1 injection, 192 received both injections, and 183 completed the study (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of participants were similar between groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Demographics of Participants.

| No. (%) of participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vaccine (n = 201) |

Placebo (n = 199) |

|

| Sex | ||

| Women | 96 (48) | 103 (52) |

| Men | 105 (52) | 96 (48) |

| Age, y | ||

| Mean (SD) [range] | 35 (12) [18- 60] | 36 (12) [18-59] |

| 18-40 | 135 (67) | 135 (68) |

| 41-60 | 66 (33) | 64 (32) |

| Racea | ||

| North, South, or Central American native (aboriginal) | 144 (71.6) | 143 (71.9) |

| Multiracial | 21 (10.4) | 20 (10.1) |

| White | 20 (10) | 14 (7) |

| Black | 3 (1.5) | 6 (3) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| Unknown or not reported | 13 (6.5) | 15 (7.51) |

| Ethnic origin | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 137 (68) | 138 (69) |

| Primary language | ||

| Spanish | 138 (69) | 140 (70) |

| Haitian Creole | 32 (16) | 30 (15) |

| French | 31 (15) | 29 (15) |

| Other | ||

| BMI, mean (SD) [range] | 26 (5.4) [16-40] | 26 (5) [17-39] |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Race data were self-reported during participant interview and based on a pick list.

The CHIKV VLP vaccine was well tolerated, with no serious adverse events related to vaccine were reported. Two hundred ninety-four participants (74%) reported no solicited local reactogenicity; 64 (32%) in the vaccine group reported at least 1 local symptom, including pain or tenderness, swelling or redness, and 37 (19%) in the placebo group reported at least 1 local symptom. In both groups, local symptoms were most often rated as mild and occasionally as moderate in severity (Table 2). For solicited systemic reactogenicity, including malaise, myalgia, headache, chills, nausea, joint pain, and fever, 87 participants (44%) in the vaccine group reported at least 1 symptom, also generally rated as mild or moderate in severity (Table 2). One participant (0.5%) in the vaccine group who reported having a history of migraines experienced a headache after the second vaccination that was graded as severe and that resolved within 1 day. Compared with placebo, there were no significant differences in solicited systemic reactogenicity in vaccine recipients, and the significant differences in local reactogenicity were pain or tenderness at the injection site (61 [31%]) in the vaccine group vs 37 [19%] in the placebo group; P = .005), as well as the overall category of any local symptom (64 [33%] in the vaccine group vs 37 [19%] in the placebo group, P = .003) (Table 2).

Table 2. Maximum Local and Systemic Reactogenicitya.

| No. (%) of participants with injection 1 + injection 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vaccine overall (n = 197) |

Placebo overall (n = 198) |

|

| Local symptoms | ||

| Pain or tenderness | ||

| Moderate | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Mild | 58 (29) | 37 (19) |

| Swelling | ||

| Moderate | 3 (2) | 1 (0.5) |

| Mild | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Redness | ||

| Moderate | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Any local symptomb | ||

| Moderate | 6 (3) | 1 (0.5) |

| Mild | 58 (29) | 36 (18) |

| Systemic symptoms | ||

| Malaise | ||

| Moderate | 7 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Mild | 46 (23) | 41 (21) |

| Myalgia | ||

| Moderate | 5 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Mild | 41 (21) | 34 (17) |

| Headache | ||

| Severe | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Moderate | 11 (6) | 11 (6) |

| Mild | 42 (21) | 47 (24) |

| Chills | ||

| Moderate | 4 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Mild | 13 (7) | 10 (5) |

| Nausea | ||

| Moderate | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Mild | 8 (4) | 12 (6) |

| Joint pain | ||

| Moderate | 4 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Mild | 20 (10) | 12 (6) |

| Feverc | ||

| Severe | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| Moderate | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Mild | 7 (4) | 2 (1) |

| Any systemic symptom | ||

| Severe | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Moderate | 21 (11) | 16 (8) |

| Mild | 65 (33) | 68 (34) |

Each vaccine recipient is counted once at worst severity for any local and systemic parameter. Unlisted participants had no local or systemic symptoms.

The number of participants experiencing any local or systemic symptom with each participant counted only once at the maximum severity of symptom experience.

Mild fever range is a temperature of 38.0-38.4 °C; moderate fever, 38.5-38.9 °C; severe fever, 39.0-40.0 °C.

Overall, 16 mild to moderate unsolicited adverse events potentially related to the innoculations occurred in 11 participants (eTable 4 in Supplement 3). The adverse events included neutropenia, bradycardia, hypotension, viral infection, rash, chest pain, dry lips, light headedness, fever, myalgia, gastroenteritis, abdominal pain, anemia, alanine aminotransferase increase, and 2 hematomas. Of these 16 adverse events, 12 (75%) occurred in 8 participants in the vaccine group. The remaining 4 adverse events (25%) occurred in 3 participants in the placebo group. All adverse events assessed as potentially related to study product resolved without clinical sequelae.

Of the 16 serious adverse events unrelated to the study drugs, 4 (25%) occurred among 4 patients in the vaccine group and 12 (75%) occurred among 11 patients in the placebo group. Fourteen of these events resolved without clinical sequelae, and 2 events involved sequelae: 1 participant had a left femur fraction; 1, an ileal perforation.

The CHIKV focus reduction neutralization test demonstrated that the vaccine was highly immunogenic and elicited a positive response in all but 1 of the 192 participants who had received both vaccinations (99.5%; 95% CI, 97.1%-100%). The GMT for vaccine group increased from 46.9 (95% CI, 33.6-62.5) at baseline to 2004.5 (95% CI, 1680.1-2392.5) at week 8 and was significantly greater than the GMT in the placebo group, which was 42.8 (95% CI, 31.7-57.9) and virtually unchanged from a baseline of 42.6 (95% CI, 31.7-57.3). The GMR of the week-8 titer to the baseline titer was 46.1 in the vaccine group vs 1.0 in the placebo group (P < .001, Figure 2, Table 3). At week 8, the younger cohort in the vaccine group had a GMT of 2332.8 (95% CI, 1866.5-2915.6) and the older cohort had a GMT of 1500.6 (95% CI, 1132.3-1988.7). Durability of the immune response was demonstrated throughout the 72-week study (GMT, 98; 95% CI, 82-118); 144 participants (88%) in the vaccine group who were seronegative at baseline had at least a 4-fold increase from baseline neutralization titers (P < .001), and 96% were seropositive according to the CHIKV luciferase neutralization assay (Figure 3 and eTable 1 in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Vaccination vs Placebo Response Among Participants Based on the Chikungunya Virus Focus Reduction Neutralization Test.

Injections occurred on weeks 0 and week 4. Vaccine recipients developed a statistically significant response at week 8 compared with placebo, with the vaccine group response more than 46-fold higher than the placebo group response (both vaccine and placebo groups: n = 192, P < .001). The lower limit of detection for the assay is indicated by the dotted line and shown for week 0 for vaccine group and both time points for the placebo group. The number of participants with effective concentration 50 (EC50) values at the lower limit of detection for the placebo group at week 0 was 156 and week 8, 151; for the vaccine group at week 0, 156 and week 8, 1. The chikungunya virus focus reduction neutralization test (Chikungunya Virus Focus Reduction Neutralization Test [CHIKV FRNT] log10 of the EC50, defined as the reciprocal dilution of sera at half-maximal neutralization of viral activity) is presented for all vaccine and placebo recipients. The geometric mean titer and 95% CIs are indicated by horizontal bars.

Table 3. Response Rates From Baseline to Week 8 Based on Chikungunya Virus Focus Reduction Neutralization Test Neutralization Assay EC50 Dilution—Immunogenicity Populationa.

| Overall | Age 18-40 y | Age 41-60 y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Placebo | P value | Vaccine | Placebo | Vaccine | Placebo | |

| Baseline | |||||||

| No. of participants | 196 | 198 | 130 | 134 | 66 | 64 | |

| GMT (95% CI) | 45.9 (33.6-62.5) |

42.6 (31.7-57.3) |

69.2 (45.0-106.5) |

53.0 (35.9-78.4) |

20.4 (15.4-27.0) |

27.0 (18.2-40.1) |

|

| Week 8 | |||||||

| No. of participants | 192 | 192 | 126 | 129 | 66 | 63 | |

| GMT (95% CI) | 2004.5 (1680.1-2391.5) |

42.8 (31.7-57.9) |

<.001 | 2332.8 (1866.5-2915.6) |

55.3 (36.9-82.9) |

1500.6 (1132.3-1988.7) |

25.4 (17.5-37.0) |

| GMR (95% CI) | 46.1 (35.4-60.2) |

1.0 (1.0-1.1) |

<.001 | 36.1 (25.3-51.5) |

1.0 (1.0-1.1) |

73.6 (51.3-105.7) |

1.0 (1.0-1.1) |

| Positive response rates at week 8 | |||||||

| No./total (%) of patients | 191/192 (99.5) | 40/192 (20.8) | 125/126 (99.2) | 32/129 (24.8) | 66/66 (100) | 8/63 (12.7) | |

| 95% CI, %b | 97.1-100 | 15.3- 27.3 | <.001c | 95.7-100.0 | 17.6-33.2 | 94.6-100.0 | 5.6-23.5 |

Abbreviations: EC50, effective concentration of the reciprocal dilution of sera at half-maximal neutralization of viral activity; GMR, geometric mean ratio; GMT, geometric mean titer.

Immunogenicity population is defined as randomized participants who received at least 1 product administration with nonmissing week-8 immunogenicity data.

Positive immune response defined as titer value greater than or equal to 30.

P value from Fisher exact test.

Figure 3. Chikungunya Virus Luciferase Neutralization Assay.

Injections occurred on week 0 and week 4. The center line of the box for each time point represents the corresponding median titer, and the upper and lower edges of the box represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The lengths of the whiskers extending above and below each box are equal to 1.5 times the interquartile range (75th percentile-25th percentile), or the distance between the most extreme data value and the corresponding quartile, whichever is shorter. Titers for individual samples that fall outside of the whiskers are represented as open circles. Postvaccination neutralization titers rose to a peak at week 8 (n = 153, P < .001), and remained well above baseline through week 72 (n = 144, P < .001). Lower limit of detection for the assay is 15, and data points for samples with titers below the assay detection of 15 are plotted at 7.5. All prevaccination titers were below the lower limit of detection. NT80 is defined as the reciprocal dilution of sera associated with an 80% reduction in viral activity.

In comparing week-8 immunogenicity data with data from the 6-trial sites, despite standardized screening processes to exclude participants who were CHIKV seropositive at baseline (up to 56 days prior to randomization), higher baseline neutralization titers were observed in both the vaccine and placebo groups among participants enrolled at the Dominican Republic and Haiti sites relative to all other sites (eTable 2 in Supplement 3). To investigate this effect, an assessment of the 168 participants enrolled in the Dominican Republic and Haiti was performed using the IgG/IgM ELISA screening kit on samples stored from the study enrollment and randomization day taken just prior to first injection. This retrospective assessment revealed elevated CHIKV antibody titers as measured in the IgG-IgM ELISA screening at study enrollment that were not detected during the screening visit that occurred up to 56 days prior to enrollment. Results showed that of the 168 samples 74 were IgG positive; 3, IgG and IgM positive; and 1, IgM positive. Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between these repeat CHIKV ELISA results and the neutralization titers at both sites in the Dominican Republic and Haiti (Spearman correlation coefficients, 0.82 and 0.54 for each site, respectively).

Post hoc analysis of immunogenicity data showed that the vaccine was immunogenic among vaccine recipients who were seropositive when first vaccinated, inducing a 2-fold increase in neutralizing antibody titer by focus reduction neutralization test after the second vaccination (Table 4; eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). There was a significant difference (P < .001) between the GMR of the seropositive vaccine recipients at 1.9 (95% CI, 1.61-2.27) and of the seronegative vaccine recipients at 96.1 (95% CI, 79.97-115.6), indicating a positive, but different degree of, vaccine-induced response between these 2 groups with different levels of background immunity (Table 4; eFigure 1 in Supplement 3).

Table 4. Response Rates to Chikungunya Virus Particle–Like Vaccine From Baseline to Week 8 Based on Focus Reduction Neutralization Test and Neutralization Assay EC50 Dilution .

| Vaccine | Placebo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seropositive | Seronegative | P value | Seropositive | Seronegative | P value | |

| Baseline No. of participants | 39 | 157 | 39 | 159 | ||

| Baseline geometric mean titer (95% CI) | 3419.4 (2700.9-4329.0) | 15.7 (14.9-16.6) | 2619.1 (1859.1-3689.7) | 15.5 (15.0-16.1) | ||

| Week 8 No. of participants | 36 | 156 | 37 | 155 | ||

| Week 8 | ||||||

| GMT (95% CI) | 6812.7 (5322.2-8720.7) | 1511.5 (1258.0-1816.0) | <.001 | 2637.3 (1839.3-3781.5) | 16.0 (14.9-17.3) | <.001 |

| GMR (95% CI) | 1.91 (1.61-2.27) | 96.14 (79.97-115.6) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.88,1-12) | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) | .94 |

| Positive response rates at week 8 | ||||||

| No./total (%) | 36/36 (100.0) | 155/156 (99.4) | >.99b | 36/37 (97.3) | 4/155 (2.6) | <.001b |

| 95% CIa | 90.3-100.0 | 96.5-100.0 | 85.8-99.9 | 0.7-6.5 | ||

Abbreviations: EC50, effective concentration of the reciprocal dilution of sera at half-maximal neutralization of viral activity; GMR, geometric mean ratio; GMT, geometric mean titer.

Positive immune response defined as titer value greater than or equal to 30.

P value from Fisher exact test.

Differences were also observed between sites in the overall pool of participants screened for trial eligibility possibly reflecting variations in CHIKV seroprevalence across study sites during the screening phase of the trial. Forty-seven percent of participants at the Dominican Republic and 57% at the Haiti sites tested positive for CHIKV or had indeterminate results on ELISA as assessed by the site vs a range of 10% to 31% at all other sites (eTable 3 in Supplement 3).

Discussion

In this phase 2 placebo-controlled trial the CHIKV VLP vaccine, VRC-CHIKVLP059-00-VP, was safe, well tolerated, and immunogenic in participants residing in CHIKV-endemic areas. The trial was designed to exclude participants who were CHIKV seropositive prior to enrollment and randomization; however, at 2 sites (Dominican Republic and Haiti) on the island of Hispaniola, 78 of 168 of trial participants were retrospectively found to be seropositive on the day of study enrollment. Participants likely seroconverted between study screening and enrollment; however, because screening samples were not stored for future use, it was not possible to retest these samples for CHIKV infection. While the 2015 outbreak was waning on the island during this time,15 it cannot be ruled out that CHIKV may have been circulating during study screening. Despite identified differences in seropositivity, the vaccine was safe and immunogenic in both enrolled populations.

The CHIKV VLP vaccine is the only protein-based vaccine currently being evaluated in clinical testing. A live-attenuated CHIKV derivative vaccine and a recombinant measles virus–based vaccine have been evaluated through phase 2 clinical trials.16,17,18 Vaccine-induced humoral immune responses reported herein are comparable with titers from participants vaccinated in the phase 1 trial of this product, and serum collected from participants in the phase 1 trial induced neutralizing antibodies against all 3 genotypes of CHIKV.1 The correlate of protection against CHIKV infection has not been clearly defined but presumed to be CHIKV–specific neutralizing antibodies supported by preclinical data evaluating factors involved in protection against CHIKV.15 High-dose challenge studies showed that the CHIKV VLP vaccine described in this report protected nonhuman primates from viremia and purified IgG from the same nonhuman primates protected immunodeficient mice from lethal CHIKV challenge, suggesting that vaccine-induced antibodies play a mechanistic role in protection.9 A recent review reported that in nonhuman primates, prechallenge neutralizing antibody titers induced by vaccination and measured by plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) were associated with robust protection against viremia when PRNT50 titers were greater than 1000.19 A natural infection study involving 853 individuals in the Philippines showed that a positive (≥10) baseline CHIKV PRNT80 titer was associated with 100% (95% CI, 46.1%-100.0%) protection from symptomatic CHIKV infection.20 In the presented study a positive response was defined as a focus reduction neutralization test titer greater than or equal to 30, representing the assay limit of detection, and 99.5% (95% CI, 97.1%-100.1%) of vaccine recipients met this criteria at week 8.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this trial only assessed safety of the CHIKV VLP vaccine through 72 weeks after administration. Additional trials are needed to identify long-term vaccine safety as well as duration of potential protection. Second, the trial design aimed to enroll only CHIKV seronegative participants; however, 20% of participants were retrospectively found to be seropositive at baseline on the day of study enrollment and no screening samples were available for retesting. Third, this trial demonstrated only safety and immunogenicity of the CHIKV VLP vaccine in both seronegative and seropositive participants; it did not evaluate vaccine efficacy or correlates of protection, which will require additional trials.

Conclusions

Among healthy adults in a chikungunya endemic population, a VLP vaccine compared with placebo demonstrated safety and tolerability. Phase 3 trials are needed to assess clinical efficacy.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Chikungunya Luciferase Neutralization Assay and Case Identification

eResults. Chikungunya Case Identification and Diagnosis

eFigure. CHIKV Focus Reduction Neutralization Test Neutralization assay for baseline CHIKV seronegative vaccine and placebo recipients

eTable 1. Durability of Immune Response in Vaccine Recipients Who Were Seronegative by Luciferase Neutralization Assay at Baseline

eTable 2. GMT, Geometric Mean Ratio, and Positive Response Rates of the Neutralization Assay of the EC50 Dilution with 95% Confidence Intervals at Baseline and Week 8 by Treatment Group and Site, Modified Intent-to-Treat (mITT) Population

eTable 3. Screening Data by Site

eTable 4. Adverse Events Potentially Related to Study Product

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Goo L, Dowd KA, Lin TY, et al. A virus-like particle vaccine elicits broad neutralizing antibody responses in humans to all chikungunya virus genotypes. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(10):1487-1491. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leparc-Goffart I, Nougairede A, Cassadou S, Prat C, de Lamballerie X. Chikungunya in the Americas. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60185-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yactayo S, Staples JE, Millot V, Cibrelus L, Ramon-Pardo P. Epidemiology of chikungunya in the Americas. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 5):S441-S445. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz O, Albert ML. Biology and pathogenesis of chikungunya virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(7):491-500. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hua C, Combe B. Chikungunya virus-associated disease. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(11):69. doi: 10.1007/s11926-017-0694-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paixão ES, Rodrigues LC, Costa MDCN, et al. Chikungunya chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2018;112(7):301-316. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/try063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kam YW, Lee WW, Simarmata D, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the human antibody response to Chikungunya virus infection: implications for serodiagnosis and vaccine development. J Virol. 2012;86(23):13005-13015. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01780-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kam YW, Simarmata D, Chow A, et al. Early appearance of neutralizing immunoglobulin G3 antibodies is associated with chikungunya virus clearance and long-term clinical protection. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(7):1147-1154. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akahata W, Yang ZY, Andersen H, et al. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med. 2010;16(3):334-338. doi: 10.1038/nm.2105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roldão A, Mellado MC, Castilho LR, Carrondo MJ, Alves PM. Virus-like particles in vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9(10):1149-1176. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushnir N, Streatfield SJ, Yusibov V. Virus-like particles as a highly efficient vaccine platform: diversity of targets and production systems and advances in clinical development. Vaccine. 2012;31(1):58-83. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang LJ, Dowd KA, Mendoza FH, et al. ; VRC 311 Study Team . Safety and tolerability of chikungunya virus-like particle vaccine in healthy adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2046-2052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61185-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pal P, Dowd KA, Brien JD, et al. Development of a highly protective combination monoclonal antibody therapy against Chikungunya virus. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(4):e1003312. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guidance for Industry: Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials US Dept of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Published September 2007. Accessed 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/73679/download

- 15.Sheet CF. World Health Organization. Updated April 4, 2017. Accessed 2019.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunya

- 16.Edelman R, Tacket CO, Wasserman SS, Bodison SA, Perry JG, Mangiafico JA. Phase II safety and immunogenicity study of live chikungunya virus vaccine TSI-GSD-218. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(6):681-685. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsauer K, Schwameis M, Firbas C, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of a recombinant measles-virus-based chikungunya vaccine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active-comparator, first-in-man trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):519-527. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70043-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reisinger EC, Tschismarov R, Beubler E, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of the measles-μvectored chikungunya virus vaccine MV-CHIK: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and active-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2019;392(10165):2718-2727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32488-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milligan GN, Schnierle BS, McAuley AJ, Beasley DWC. Defining a correlate of protection for chikungunya virus vaccines. Vaccine. 2019;37(50):7427-7436. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon IK, Alera MT, Lago CB, et al. High rate of subclinical chikungunya virus infection and association of neutralizing antibody with protection in a prospective cohort in the Philippines. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(5):e0003764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Chikungunya Luciferase Neutralization Assay and Case Identification

eResults. Chikungunya Case Identification and Diagnosis

eFigure. CHIKV Focus Reduction Neutralization Test Neutralization assay for baseline CHIKV seronegative vaccine and placebo recipients

eTable 1. Durability of Immune Response in Vaccine Recipients Who Were Seronegative by Luciferase Neutralization Assay at Baseline

eTable 2. GMT, Geometric Mean Ratio, and Positive Response Rates of the Neutralization Assay of the EC50 Dilution with 95% Confidence Intervals at Baseline and Week 8 by Treatment Group and Site, Modified Intent-to-Treat (mITT) Population

eTable 3. Screening Data by Site

eTable 4. Adverse Events Potentially Related to Study Product

Data Sharing Statement