Abstract

Background/Aim: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is an indicator of systemic inflammation and could be a predictive factor in malignant tumors. The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of NLR in patients with lower rectal cancer who received preoperative chemo-radiotherapy (CRT). Patients and Methods: Forty-eight patients with lower rectal cancer who underwent preoperative CRT and curative resection were enrolled. Blood samples were obtained before and after CRT. The relationship of NLR with clinical outcome was investigated. Results: Post-CRT NLR was higher compared to pre-CRT NLR. The patients with higher post-CRT NLR tended to have worse pathological response to CRT compared to those with low post-CRT NLR. The patients with high post-CRT NLR showed poorer 5-year overall survival and 3-year disease free survival while there was no correlation according to pre-CRT NLR. The univariate analysis showed that post-CRT stage and post-CRT NLR were associated with a poorer 5-year overall survival. Conclusion: NLR after preoperative CRT could be a potential prognostic indicator for patients with lower rectal cancer.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, NLR, preoperative chemoradiotherapy

Preoperative chemo-radiotherapy (CRT) has become standard treatment for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (RC) because it could down-stage cancer, resulting in a lower rate of postoperative local recurrence and a higher rate of preservation of sphincter in surgery as well as longer survival (1-3). However, in unresponsive cases it could have disadvantages such as delaying surgery or suppressing immune response. Although it has been suggested that clinical factors (4,5), radiologic findings (6,7) and molecular markers (8-10) are related to the therapeutic response, the clinical usefulness of these markers remains controversial. Identifying factors that can predict the efficacy of neoadjuvant CRT is important for deciding in the management of patients with RC. In our previous report, the usefulness of CRT for lower RC and potential predictive biomarkers such as microRNA-223 have been reported (11).

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been suggested as a marker of the systemic inflammatory response in critical care patients (12). NLR can be easily calculated from routine complete blood counts in peripheral blood. It has been reported to be a useful prognostic indicator in some solid malignancies such as colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, urethral cancer and bladder cancer (13-17). Zhou et al. have reported that NLR is an independent prognostic indicator for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing CRT and changes in NLR levels with treatment may indicate its therapeutic benefit (18).

Kitayama et al. have reported that in the case of lower RC, peripheral blood lymphocytes have a significant impact on complete response rate of radiotherapy (RT) and suggested that lymphocyte-mediated immune reactions have a positive role in the responses to radiotherapy (19,20). To date, there have been few studies examining the role of NLR, especially post-CRT NLR in RC and its role remains controversial. The aim of this study was to examine the prognostic significance of NLR at both of pre- and post-CRT phases in patients with lower RC who underwent CRT.

Patients and Methods

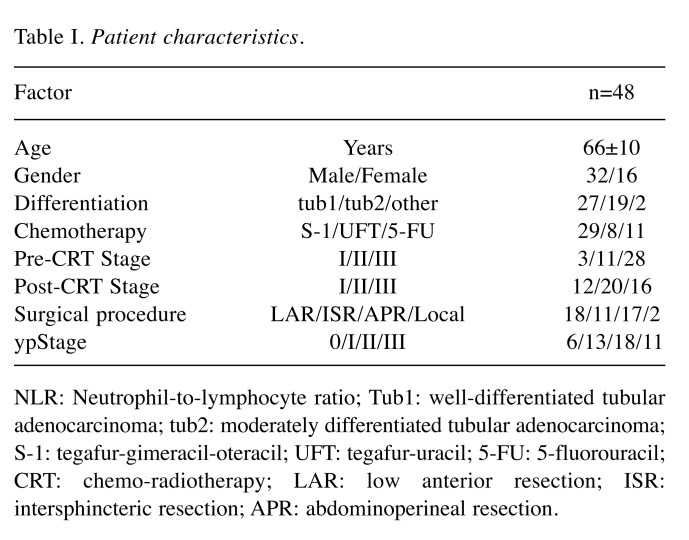

Patients. Forty-eight patients newly diagnosed with lower RC who underwent CRT at the Department of Surgery in Tokushima University Hospital between 2004 and 2012 were enrolled in this study. The study protocol was approved by the Tokushima University Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee and informed consent was obtained from all the participating patients. The patients’ clinical data, including medical history, physical examination, laboratory analysis and clinical staging were retrospectively reviewed from the medical records. Blood examinations for pre-CRT and post-CRT were conducted on the first day of CRT and within one week after the final day of CRT. The characteristics of the patients are listed in Table I.

Table I. Patient characteristics.

NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; Tub1: well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; tub2: moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; S-1: tegafur-gimeracil-oteracil; UFT: tegafur-uracil; 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil; CRT: chemo-radiotherapy; LAR: low anterior resection; ISR: intersphincteric resection; APR: abdominoperineal resection.

Treatment. Twenty-nine patients received tegafur-gimeracil-oteracil (S-1) based CRT, eight patients received tegafur-uracil (UFT) and eleven patients received intravenously 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). The following criteria were fulfilled: i) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0-2; ii) white blood cell count ≥4,000/mm3; iii) platelet count ≥100,000/mm3; iv) serum total bilirubin <1.5 mg/dl; v) creatinine <1.5 mg/dl; and vi) heart function (stable cardiac rhythm, no active angina and no clinical evidence of congestive heart failure). The treatment schedule has been described in a previous report (11). S-1 (80 mg/m2) or UFT (300 mg/m2) was orally taken five days per week, over five weeks. 5-FU (600 mg/m2) was intravenously administered on days 1, 8, 15 and 26. A total of 40Gy RT was delivered at 2.0 Gy per fraction daily on five days per week over four weeks. Within six to eight weeks after CRT, forty-six patients underwent a total meso-rectal excision, namely lower anterior resection, intersphincteric resection or abdominoperineal resection and two patients underwent local resection. The effects of CRT were evaluated by pathologists according to the Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma. In three patients, pathological examination of the resected specimen detected no tumor cells at either the primary site or in regional lymph nodes, confirming the pathological complete response (pCR). The patients were followed up postoperatively for five years by the levels of tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and computed tomography every three months to diagnose the recurrence of the disease.

Parameters. NLR was calculated pre-CRT and post-CRT. Median cut-off values of 2.45 for pre-CRT and 3.85 for post-CRT were used to divide the patients into low NLR and high NLR groups. The clinicopathological factors, overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were compared according to NLR pre-CRT and post-CRT, respectively.

Statistics. Statistical analyses were carried out using the JMP 10 statistical software package (SAS Institute Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The Student’s t-test was used for comparison of the continuous variables. The chi-squared test was used to analyze the relationship between the NLR and the clinicopathological characteristics. The patients’ survival data were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed by the log-rank test to calculate differences between the curves. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

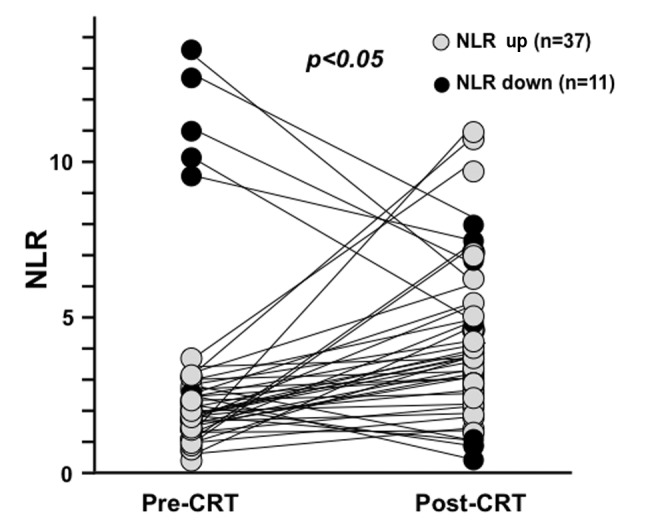

The changes of NLR from pre-CRT to post-CRT. The median value of pre-CRT NLR was 2.45 and that of post-CRT NLR was 3.85. The post-CRT NLR was significantly higher than pre-CRT NLR (Figure 1). In thirty-seven patients, NLR increased after CRT while it decreased in eleven patients. It was notable that three patients with low pre-CRT NLR had the highest three post-CRT NLRs.

Figure 1. The changes of NLR from pre-CRT to post-CRT. NLR was increased in 37 patients and decreased in 11 patients after CRT. Median value of NLR was 2.45 before CRT and 3.85 after CRT.

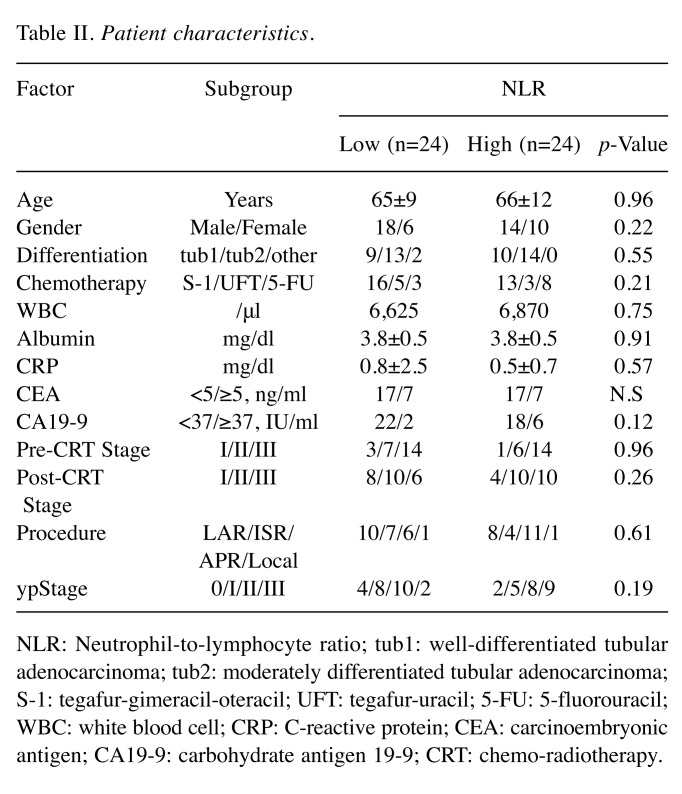

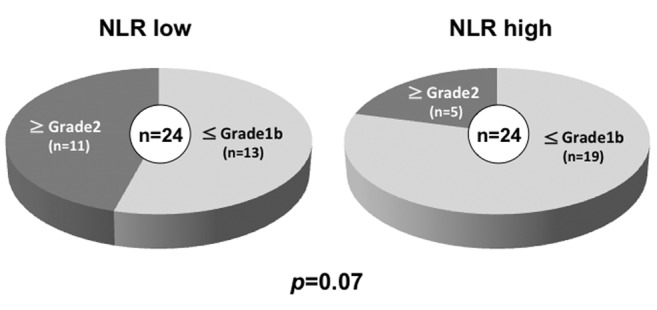

The association between the NLR and the clinicopathological factors. The post-CRT NLR tended to be correlated with the pathological response of CRT (Figure 2). About 45.8% of the patients in the low NLR group and 20.8% in the high NLR group had a pathological response greater than grade 2. No correlation was observed according to pre-CRT NLR. There was no difference in the listed clinicopathological factors according to post-CRT NLR (Table II).

Figure 2. Pathological response to CRT according to post-CRT NLR. Patients with high post-CRT NLR tended to have worse pathological response compared to those with low NLR (p=0.07).

Table II. Patient characteristics.

NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; tub1: well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; tub2: moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; S-1: tegafur-gimeracil-oteracil; UFT: tegafur-uracil; 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil; WBC: white blood cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CRT: chemo-radiotherapy.

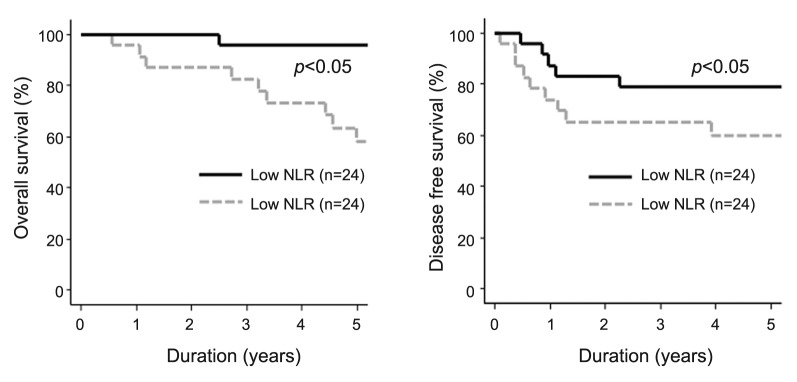

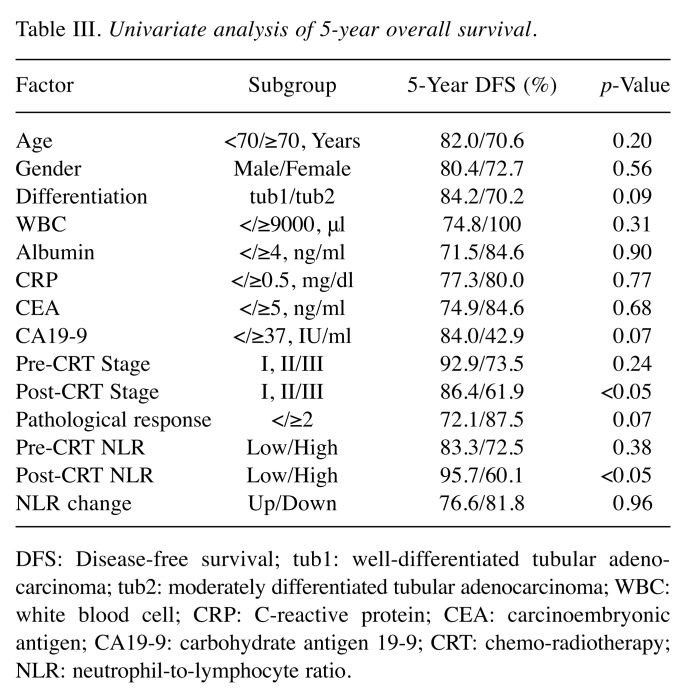

The significance of the NLR on the prognosis. As shown in Figure 3, patients with high post-CRT NLR had significantly poor DFS (3-year DFS: high NLR 62.6% vs. low NLR 82.6%: p<0.05) and OS (5-year OS: high NLR 60.1% vs. low NLR 95.7%: p<0.05), whereas pre-CRT NLR was not significantly associated with DFS (3-year DFS: high NLR 79.3% vs. low NLR 70.4%: N.S) and OS (5-year OS: high NLR 82.3% vs. low NLR 84.8%: N.S.). Univariate analysis of 5-year OS revealed that post-CRT stage and post-CRT NLR were significant prognostic factors while the change of NLR from pre-CRT to post-CRT was not determined to be a significant prognostic factor (Table III).

Figure 3. Overall and disease-free survival according to post-CRT NLR. Patients with high post-CRT NLR showed significantly worse outcome than those with low NLR.

Table III. Univariate analysis of 5-year overall survival.

DFS: Disease-free survival; tub1: well-differentiated tubular adeno - carcinoma; tub2: moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; WBC: white blood cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CRT: chemo-radiotherapy; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Discussion

Inflammation has been suggested as a hallmark of cancer (21,22). A systemic inflammatory response leads to angiogenesis, inhibition of apoptosis, and DNA damage (12,23). It has been postulated that markers of systemic inflammation may provide useful information for prognosis. Various markers of systemic inflammatory response such as cytokines, C-reactive protein (CRP), Glasgow prognostic score, NLR and platelet to lymphocyte ratio have prognostic roles in various common solid tumors, and the value of a systemic inflammatory response has been extensively examined in CRC (24-27). An elevated CRP level in response to systemic inflammation has been noted to be a particularly important factor in the nutritional and functional decline of patients with advanced cancer (28).

The NLR is a factor related to systemic inflammation and it can be obtained simply and easily by a routine blood examination. The correlation between NLR and prognosis of patients with CRC has been firstly reported by Walsh et al. (13). They reported that preoperative NLR>5 is predictive of OS and cancer-specific survival in univariate analysis. In other reports, elevated NLR has been associated with poor outcome and the NLR has been shown to be a prognostic factor in patients with resectable or unresectable CRC (29,30). In the present study, it was demonstrated that a high post-CRT NLR could be a predictive marker for poor response to CRT and prognosis after the following curative surgery. In the current study, post-CRT NLR was higher than pre-CRT NLR although there was no difference in the total WBCs, indicating a decrease of lymphocytes, which is consistent with a previous report by Kitayama et al. (20). Since lymphocytes, especially T cells play a central role in anti-tumor immunity, the decrease of NLR after CRT might reflect the overall ability of the host to fight cancer. In contrast, the neutrophils could have a pro-tumor effect in the microenvironment and can influence the environment throughout the stages of tumor progression. An elevated post-CRT NLR was predictive of the patients’ OS and DFS as shown in Figure 3, whereas Kim et al. have previously reported that the pre-CRT NLR could predict the pathologic response and cancer-specific survival and a pre-CRT NLR more than three was identified more frequently in the poor response group (31). Sung et al. have described the prognostic value of both the pre-CRT NLR and the post-CRT NLR and a persistently elevated post-CRT NLR may be an indicator of an increased risk of distant metastasis (32). Cha et al. have indicated persistent lower NLR as an independent favorable prognosticator of DFS in patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative CRT (33). Kim et al. have reported that a pre-CRT NLR of more than three was more frequently identified in the poor response group (31). In the present study, an elevated post-CRT NLR tended to be correlated with poor pathological response of CRT (Figure 2).

This study has some limitations, one of which is the small sample size. The pre- and post-CRT NLR were evaluated retrospectively. NLR was dichotomized as greater or less than the median value of the data set, namely 2.45 for the pre-CRT NLR and 3.85 for the post-CRT NLR. To date there has been no consensus about the NLR cut-off value that varies between reports from 1.75 to 5.14 (31-33). Further prospective, multicenter studies are needed to validate the results of this study and to determine the appropriate cut-off value. Based on the results of this study, a high post-CRT NLR might be utilized as a predictor for more advanced disease features. Accordingly, patients with high NLR might be considered for adjuvant treatment (34,35). In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that the NLR could be an important predictive factor of the response to CRT and the prognosis for patients with lower RC after surgery.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the Authors has any potential financial conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Authors’ Contributions

Ishikawa D designed and carried out the experiments and wrote the initial draft of the article. Takasu C and Kashihara H contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. Tokunaga T and Higashijima J contributed to data collection and interpretation. Nishi M and Yoshikawa K assisted in the preparation of the article. Shimada M supervised the project. All Authors have critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version of the article.

References

- 1.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rodel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, Martus P, Tschmelitsch J, Hager E, Hess CF, Karstens JH, Liersch T, Schmidberger H, Raab R, German Rectal Cancer Study G Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(17):1731–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, Daban A, Bardet E, Beny A, Ollier JC, Trial ERG. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(11):1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortholan C, Francois E, Thomas O, Benchimol D, Baulieux J, Bosset JF, Gerard JP. Role of radiotherapy with surgery for T3 and resectable T4 rectal cancer: Evidence from randomized trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(3):302–310. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das P, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Feig BW, Chang GJ, Wolff RA, Eng C, Krishnan S, Janjan NA, Crane CH. Predictors of tumor response and downstaging in patients who receive preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1750–1755. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park HC, Janjan NA, Mendoza TR, Lin EH, Vadhan-Raj S, Hundal M, Zhang Y, Delclos ME, Crane CH, Das P, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, Krishnan S. Temporal patterns of fatigue predict pathologic response in patients treated with preoperative chemoradiation therapy for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(3):775–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kremser C, Trieb T, Rudisch A, Judmaier W, de Vries A. Dynamic T(1) mapping predicts outcome of chemoradiation therapy in primary rectal carcinoma: Sequence implementation and data analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(3):662–671. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konski A, Li T, Sigurdson E, Cohen SJ, Small W Jr., Spies S, Yu JQ, Wahl A, Stryker S, Meropol NJ. Use of molecular imaging to predict clinical outcome in patients with rectal cancer after preoperative chemotherapy and radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang SM, Wang RB, Yu JM, Zhu KL, Mu DB, Xu ZF. Correlation of VEGF and Ki67 expression with sensitivity to neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal adenocarcinoma. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2008;30(8):602–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuchi M, Mikami T, Sato T, Tokuyama W, Araki K, Watanabe M, Saigenji K, Okayasu I. High ki67, bax, and thymidylate synthase expression well correlates with response to chemoradiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancers: Proposal of a logistic model for prediction. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(1):116–123. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuremsky JG, Tepper JE, McLeod HL. Biomarkers for response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(3):673–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakao T, Iwata T, Hotchi M, Yoshikawa K, Higashijima J, Nishi M, Takasu C, Eto S, Teraoku H, Shimada M. Prediction of response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy and establishment of individualized therapy in advanced rectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015;34(4):1961–1967. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts--rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2001;102(1):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Goulder F, Justin TA, Keeling NJ. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91(3):181–184. doi: 10.1002/jso.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue P, Kanai M, Mori Y, Nishimura T, Uza N, Kodama Y, Kawaguchi Y, Takaori K, Matsumoto S, Uemoto S, Chiba T. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for predicting palliative chemotherapy outcomes in advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2014;3(2):406–415. doi: 10.1002/cam4.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azab B, Bhatt VR, Phookan J, Murukutla S, Kohn N, Terjanian T, Widmann WD. Usefulness of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in predicting short- and long-term mortality in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(1):217–224. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalpiaz O, Pichler M, Mannweiler S, Martin Hernandez JM, Stojakovic T, Pummer K, Zigeuner R, Hutterer GC. Validation of the pretreatment derived neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in a european cohort of patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(10):2531–2536. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawahara T, Furuya K, Nakamura M, Sakamaki K, Osaka K, Ito H, Ito Y, Izumi K, Ohtake S, Miyoshi Y, Makiyama K, Nakaigawa N, Yamanaka T, Miyamoto H, Yao M, Uemura H. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a prognostic marker in bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:185. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2219-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou XL, Li YQ, Zhu WG, Yu CH, Song YQ, Wang WW, He DC, Tao GZ, Tong YS. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker for patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42581. doi: 10.1038/srep42581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitayama J, Yasuda K, Kawai K, Sunami E, Nagawa H. Circulating lymphocyte number has a positive association with tumor response in neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for advanced rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:47. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitayama J, Yasuda K, Kawai K, Sunami E, Nagawa H. Circulating lymphocyte is an important determinant of the effectiveness of preoperative radiotherapy in advanced rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan TP, Arekapudi A, Metha J, Prasad A, Venkatraghavan L. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as predictor of mortality and morbidity in cardiovascular surgery: A systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(6):414–419. doi: 10.1111/ans.13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMillan DC, Crozier JE, Canna K, Angerson WJ, McArdle CS. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (gps) in patients undergoing resection for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(8):881–886. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roxburgh CS, Salmond JM, Horgan PG, Oien KA, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of inflammation-based pathologic and biochemical criteria in patients undergoing potentially curative resection for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;249(5):788–793. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a3e738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leitch EF, Chakrabarti M, Crozier JE, McKee RF, Anderson JH, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of selected markers of the systemic inflammatory response in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(9):1266–1270. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMillan DC. Systemic inflammation, nutritional status and survival in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(3):223–226. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832a7902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6(1):149–163. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon HC, Kim SH, Oh SY, Lee S, Lee JH, Choi HJ, Park KJ, Roh MS, Kim SG, Kim HJ, Lee JH. Clinical significance of preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte versus platelet-lymphocyte ratio in patients with operable colorectal cancer. Biomarkers. 2012;17(3):216–222. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.656705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chua W, Charles KA, Baracos VE, Clarke SJ. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio predicts chemotherapy outcomes in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(8):1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim IY, You SH, Kim YW. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts pathologic tumor response and survival after preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancer. BMC Surg. 2014;14:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-14-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sung S, Son SH, Park EY, Kay CS. Prognosis of locally advanced rectal cancer can be predicted more accurately using pre- and post-chemoradiotherapy neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios in patients who received preoperative chemoradiotherapy. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cha YJ, Park EJ, Baik SH, Lee KY, Kang J. Prognostic impact of persistent lower neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio during preoperative chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients: A propensity score matching analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0214415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitade H, Shimasaki T, Igarashi S, Sakuma H, Mori M, Tomosugi N, Nakai M. Long-term administration and efficacy of oxaliplatin with no neurotoxicity in a patient with rectal cancer: Association between neurotoxicity and the gstp1 polymorphism. Oncol Lett. 2014;7(5):1499–1502. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Stojanovic-Rundic S, Bensadoun RJ, Bardet E, Beny A, Ollier JC, Bolla M, Marchal D, Van Laethem JL, Klein V, Giralt J, Clavere P, Glanzmann C, Cellier P, Collette L, Group ERO. Fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: Long-term results of the eortc 22921 randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):184–190. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]