Natural Behavior and Domestication

The question as to why ferrets were domesticated may be more easily answered than when the domestication process took place and from what molecular phylogeny. This is in part because of the scarcity of written records from 2000 years ago and because of difficulties in identification of which species was actually being domesticated. Vernacular names for the animal we presume to be the ferret frequently varied from geographic district to district, and ancient scientists may have added to the confusion with incorrect translations from one language to another.43

Domestication is the process by which human selection and control of breeding results in an animal that provides a service or product that is beneficial to humans. With time, domestication results in physical and physiologic changes from the ancestral species. Animals are domesticated for work, food, or materials for clothing and shelter. Ferrets were in all probability originally used by man to control vermin. The earliest written account of an animal that fits the description of our domesticated ferret dates back to the Greek satiric writer Aristophanes (448-385 BC), who used the term “house ferret” in several of his plays to satirize political opponents. Soon thereafter, in 350 BC, the Greek philosopher and naturalist Aristotle (384-322 BC) also made written reference in a treatise on animals and physiognomy to a polecat that “resembles a weasel; and becomes very mild and tame.”43 It is reasonable to suppose he was referring to the ferret, and the demeanor of the animal described implies a close association with people. These early written accounts coincide with the time (circa 300 BC) when agriculture began to take hold in the civilized regions of the northern Mediterranean region centered around present-day Greece. One theory suggests the Greeks domesticated the indigenous European polecat (Mustela putorius) in order to protect grain stores from rodent infestation much in the way the Egyptians domesticated the cat.

Completely carnivorous, the polecat (ferret) will take a wide variety of prey, including hares, rabbits, mice, voles, and rats. The efficiency with which the ferret hunts rabbits brought it into favor with people. Strabo (63 BC–24 AD), a Greek historian, philosopher, and geographer, reported that the Romans used ferrets to control the overpopulation of rabbits on the Balearic Islands: “The ferrets with their claws drag outside all the rabbits they catch, or else force them to flee into the open, where men, stationed at the hole, catch them as they are driven out.”43 By the Middle Ages, man was ferreting rabbits throughout Europe and Asia (Figure 4-1 ).

Figure 4-1.

Ferreting in the Middle Ages—approximately 1300 AD.

(From Thompson AD: A History of the ferret, J Hist Med 6(4):471-480, 1951.)

© 2006

Many historians believe that eleventh-century Normans introduced ferrets to Britain, where they were used to chase rabbits out of burrows. The sport of ferreting (hunting for rabbits) resulted in further domestication, as the ferret did not catch its prey but chased or frightened the rabbit out of its hole with its strong musky smell. The fleeing rabbit would then be caught in nets or by dogs or hawks used by the hunters.

This may also explain the ferret's musky body odor. Ferrets with a strong scent would make better ferreters and therefore were bred. The goal was to chase prey, not capture it. Ferrets that caught and ate the rabbits not only would destroy the food source and pelt but also would be more difficult to retrieve from the rabbit burrow. To discourage prey capture, working ferrets sometimes were harnessed with string, had bells attached to their collars, or were muzzled. With time the instinct to hunt and kill was bred out of the ferret. The sport of ferreting is still practiced by many people in Europe and Australia but is outlawed in the United States and Canada.

It is believed ferrets were brought to the United States in the late eighteenth century and used to control shipboard vermin on long, transatlantic crossings.37 In the mid nineteenth century ferrets were bred for their fur, a practice that continued late into the twentieth century. Only recently has fur production fallen out of favor in much of the world.

Ferrets have been kept as companions by historical figures such as Genghis Khan and Queen Elizabeth I; however, their popularity as pets did not increase until the late 1960s. This resulted in additional physical and behavioral changes as ferrets were bred for greater docility, decreased odor, preferred body confirmation, coat color, and failure to thrive in the wild. The last half of the twentieth century also saw the domestic ferret grow in popularity as a laboratory and research animal.

This ferret domestication timeline brings us to the present day, but the precise parent species of the domestic ferret remains uncertain. Ferrets may have been domesticated from the European polecat or from its eastern congener, the steppe polecat (Mustela eversmannii), which has more similar morphology of the cranium. Because M. putorius and M. eversmannii are occasionally reported to hybridize where they overlap in their distribution, the reality of a true species split has been debated, and several authors have at least considered whether M. putorius, M. eversmannii, and the endangered Mustela nigripes from North America (black-footed ferret) could be viewed as one Holarctic species.13

Regardless, in 1758 the domestic ferret was classified by Linnaeus as a separate genus and called Mustela furo. At that time it was believed that the steppe polecat was the most closely related to the domestic ferret. In 1970, through the examination of external chromosome shape, it was determined that the European polecat was closer to the domestic ferret than the steppe polecat. When this evidence came to light it was decided M. putorius and the domestic ferret were one and the same species, and the domestic ferret was then renamed M. putorius furo to distinguish it from the polecat.5

In 1998 Davison and co-workers13 used mitochondrial DNA sequencing to investigate polecat genetic diversity in Britain. Molecular genetics, however, did not resolve whether ferrets were originally domesticated from M. putorius or M. eversmannii. The degree of nuclear introgression* of domestic ferrets and polecats may be so extensive as to rule out ever tracing their wild ancestors.

It must be emphasized that the behavior of domesticated animals in captivity differs from that of tamed wild animals and that these behavioral differences have arisen as a result of selection by humans.5 The exact form taken by such selection will, however, depend on the role of the particular domesticated animal in relation to people. Behaviorally there are major differences between domestic ferrets and the ancestral polecat. Polecats tend to be solitary and very territorial with fighting between males having been observed, presumably over territory and sexual domain. The domestic ferret on the other hand is very social and gregarious, enjoying play activities with conspecifics and preferring to sleep with other ferrets of the same or opposite sex.

The polecat is quick, nervous, and easily frightened and will show fear of people if left with the mother during the critical period of 7½ to 8½ weeks of age.34 The domestic ferret, however, was initially kept as a pest destroyer, normally raised in confinement and liberated to the field in order to hunt the intended prey. Therefore these ferrets were raised to be easily handled and could not be nervous or fearful of humans. Further resemblance and disparities between the domestic ferret and the wild polecat will be made in other sections of this chapter as we investigate the behavior of today's pet ferret.

Sensory Behaviors

Vision and Behavior

Being domesticated from a crepuscular species, ferrets possess a tapetum lucidum, which allows for more effective vision at low levels of light. They do not see well in pitch dark and have difficulty adjusting to bright light. This means that a ferret must be allowed to adjust to the light and become fully awake before it is removed from under a blanket or from a cozy spot where it is sleeping, or the handler risks being bitten.

Ferrets have binocular vision, and although they can swivel their eyes to look at different objects, most ferrets look forward and turn their heads to see things to the side. The pupil is horizontally slit, which is common in species that chase prey with gaits characterized by a hopping motion39 and explains the ferret's fascination with a bouncing ball. Ferrets have very good visual acuity at close range, which is important because the ferret uses varying body language and visual displays to communicate.28 They see less detail at greater distances and as a result pay more attention to complex visual stimuli such as moving objects.

Hearing and Behavior

The ear canals of a ferret do not open until approximately 32 days postnatally (as compared with 6 days in a cat), which coincides with the appearance of a startle response to loud hand claps and the recording of acoustically activated neurons in the midbrain (Figure 4-2 ).31 This late onset of hearing may explain why kits produce exceptionally loud, piercing sounds during the first 4 weeks of life. Lactating jills are tuned in to kit vocalizations and will respond to high-frequency (greater than 16 kHz) sounds in a maze test, whereas males and nonlactating females will ignore these sounds.39 Adult ferrets hear best when sounds are within a range of 8 to 12 kHz.39 This may explain why ferrets love squeaky toys, which produce sounds in this range.

Figure 4-2.

The ear canals of ferrets do not open until approximately 32 days postnatally, as compared with 6 days in cats. This late onset of hearing may explain why kits produce exceptionally loud, piercing sounds during their first 4 weeks of life.

(Courtesy Peter Fisher.)

Olfactory Behaviors

Kits of wild polecats have a critical period of learning the scent of prey (olfactory imprinting), which according to Apfelbach (1986) is between 60 and 90 days of age.1 Except under duress, polecats will refuse to eat any prey whose smell they have not learned by that time.39 As adults, they will actively search for prey with which they were familiarized during this critical time period and will ignore other prey or food smells. This may explain why certain ferrets will eat only one type of diet and why kits exposed to only one brand of food at 60 to 90 days of age may be opposed to dietary changes later in life. It is therefore recommended that young kits be offered a variety of foods during their first 6 months of life in order to prevent dietary selectivity or olfactory imprinting.

The sense of smell in ferrets is particularly keen. Wild mustelidae hunt down their prey using their sense of smell to home in on the quarry. During exploratory behavior the ferret spends a great deal of time with its nose to the ground investigating its environment. Objects placed directly in front of a ferret will be examined first by smelling, followed by visual or tactile inspection.

Communication Behaviors

Olfactory Communication

Polecats are a solitary species and leave marks throughout their home range by performing a repertoire of scent-marking actions that include wiping, body rubbing, and the anal drag (Figures 4-3 and 4-4 ).10 Observations of ferrets in an outside enclosure revealed that anal drags were performed at latrines near den sites and at an equal frequency by males and females throughout the year.10 Mustelidae also use urine for scent-marking and produce skin oils that are profoundly affected by circulating hormone levels. Hobs (male ferrets) in particular will produce intense seasonal skin oils that correspond to the increased testosterone levels associated with longer day lengths.

Figure 4-3.

The anal drag. The domestic ferret defines its territory by marking behavior such as backing into corners to defecate and following with the anal drag, as illustrated here.

(Illustration courtesy Barb Lynch.)

Figure 4-4.

Wiping behavior. Domestic hobs possess preputial sebaceous glands that produce oils that they will wipe or mark on household items to communicate sexuality and territoriality. This behavior corresponds to the increased testosterone levels associated with longer day lengths.

(Illustration courtesy Barb Lynch.)

Ferret anal scent gland odors are sexually dimorphic, and studies have demonstrated that ferrets can use these variations as a communication tool.11 Ferrets can distinguish between male and female anal sac odors, among strange, familiar, and their own odors, and between fresh and 1-day-old odors.11 These results are consistent with both a sex attraction role and a territorial defense role for anal sac odors.

Different messages are conveyed by the various marks. Kelliher and Baum22 showed that in the ferret, olfactory detection and processing of volatile odors from conspecifics is required for heterosexual mate choice.22 Males perform more body rubbing than females (jills), especially during the breeding season. Anal drags leave an olfactory signature of anal sac secretion for intersexual and intrasexual communication. Olfactory marking behavior also communicates territoriality and gives other ferrets knowledge of the marking ferret's sex and hormonal activity. Wiping and rubbing actions release the ferret's general body odor and may act as a threat signal in agonistic encounters.10

The response to olfactory stimuli and the scent-marking behavior of domestic ferrets is much less pronounced than that of their undomesticated counterparts. Domestic ferrets retain the actions of marking that are so important to their wild relatives.39 The ferret thrives in the company of other ferrets; readily sharing living quarters, hammocks in which they sleep, food bowls, and water bottles. Despite this harmony, ferrets are still instinctively territorial and lay claim to smaller, albeit significant territories within their home environment. Like the wild polecat, domestic ferrets back up and defecate on objects or certain areas (and some even anal drag after defecation) in order to mark their territory. The domestic ferret tends to choose corners in which to defecate that may represent territory perimeters.

When it comes to the postdefecation anal drag, operators of ferret shelters will note that this behavior will increase in some ferrets when a new ferret is introduced to the household or when ferrets become more seasonally hormonal.25 This innate behavior occurs even in ferrets that are surgically descented (anal sacculectomy), as the ferret is unaware of its missing anatomy. Ferrets also possess perianal sebaceous glands that secrete oils used in scent-marking. The strength of the scent from these glands is reduced in neutered males.

Worth mentioning is the way in which ferrets use their sense of smell in meet-and-greet behavior. When ferrets are introduced they will often sniff each other's anal area and neck and shoulder region (Figure 4-5 ). This behavior may give a domestic ferret information about the other ferret's sex and hormonal status. This activity may be the domestic ferret's equivalent of the behavior in the wild counterpart by which sexual receptivity is assessed.

Figure 4-5.

Meet-and-greet behavior. When ferrets are introduced, they will often sniff each other's anal area and the neck or shoulder region. This behavior may give the domestic ferret information about the other ferret's sex and hormonal status.

(Courtesy Laura Powers.)

Vocalizations

Although quiet most of the time, domestic ferrets do make a variety of vocalizations with which they communicate. In order to determine the meaning of ferret sounds, Shimbo39 recorded waveforms and sound spectrographs of various domestic ferret vocalizations. Interpretation of these auditory studies led to several generalizations such as an increase in tonality on a basic signal indicates heightened excitement, a rising inflection indicates urgency, and a rising pitch of a string of sounds indicates displeasure.39 Any one or more of these alterations in inflection can be superimposed on any vocalization to alter its meaning. The following are descriptions and the interpretive significance of the most common ferret vocalizations as recognized by many ferret owners.

Dook

Also know as chuckling or “the buck,” the dook is the most commonly used ferret vocalization. This vocal signal can be low- or high-pitched and is usually strung together in a series of chortles or chucks in undulating pitches. The dook usually signifies happiness or excitement and is commonly expressed during play and exploratory behavior. The greater the excitement level is, the louder are the intensity and volume.

Hiss

The ferret and most other mustelidae use a hissing sound to convey anger and frustration, but it can also denote fear or be used as a warning signal. It can be a short burst that warns a playing partner, “Hey, that hurt, back off a little,” or serves as a fear response, forewarning that “my guard is up, be careful.” Prolonged hissing usually indicates frustration.

Scream

A high-pitched screech is used when a ferret is startled, frightened, or in pain. When cornered by another animal, ferrets may scream to startle their opponent and thereby gain escape. Prolonged screaming is an indication that something is seriously wrong and may occur when a ferret is in intense pain; such screaming has also been reported to occur during seizures.6 All cases of continual or recurrent screaming warrant a medical workup.

Bark

An unusual loud chirp may occur as a defensive vocalization when a ferret is frightened or very excited. Some ferrets bark when they are angry. It is usually easy to discern a happy, curious ferret vocalization from one indicating anger, fear, or extreme pain. Be aware that an apprehensive or distressed ferret may bite, and use appropriate caution with ferrets that are using these verbal signals.

Visual

Ferrets also use body language and a variety of visual displays to communicate moods and feelings. They prefer to follow and attack prey moving at a velocity close to the escape speed of a mouse.45 This may help to explain their fascination with bouncing balls, toys pulled along the ground in front of them, and in general anything that moves. During exploration the inquisitive ferret will periodically demonstrate scouting behavior in the form of erect or alert posturing. This attention response is similar to (and probably stems from) actions shown by the European polecat while investigating unfamiliar surroundings. During this response the neck is raised, the head is held at 90 degrees to the body, the ears are pricked, and the vibrissae are extended.39

Piloerection in the form of a frizzed-out tail may be a sign of anger or excitement, either fearful or joyous (Figure 4-6 ). During a display of anger, the puffed tail is usually accompanied by an arched back and a vocal hiss or screech. If the display represents excitement and joy, the tail may fuzz out and flick back and forth. Piloerection of the tail may also be noted during an anaphylactic reaction such as that seen with a vaccine reaction.

Figure 4-6.

Bottle brush tail. Piloerection in the form of a frizzed-out tail may be a sign of anger or excitement, either fearful or joyous. During a display of anger the puffed tail is usually accompanied by an arched back and a vocal hiss or screech. If the display represents excitement and joy, the tail may fuzz out and flick back and forth.

(Courtesy Lisa Leidig.)

Locomotor Behaviors and Activity

Normal locomotion in a ferret consists of alternating movements of all four feet, although a ferret can be seen to hop or gallop with the rear legs when running or at play. Many repeatable locomotor patterns can be noted that tell us the ferret is a happy, playful pet; these activities have been described and nicknamed by ferret owners.37 For example, the “dance of joy” or the “weasel war dance” is exhibited by the ferret that is happy and excited. The animated ferret tries to go in several directions at once; dancing from side-to-side, hopping forward, twisting back, flipping and rolling on the floor—all at an energetic pace. There seems to be no apparent reason for this dance other than pure joy and happiness.

The “alligator roll” is a form of intense play or wrestling between two ferrets where one ferret grabs the other by the back of the neck and flips him upside down. Some feel this is a way for one ferret to show dominance.6 Because wild ferrets are solitary, any form of social hierarchy would be a reflection of domestication and the housing of multiple unrelated ferrets in close captivity. It is obvious that ferrets are energetic, fun-loving animals. As a result of this high energy, ferrets need ample play time (preferably up to 2 hours per day) and benefit greatly from environmental enrichment.

In addition to the “dance of joy” and the “alligator roll” already discussed, play behavior may include other visual displays. During periods of intense play ferrets may suddenly stop, fall to the ground, and slump, with body flattened, eyes open, and back legs splayed. This usually indicates the ferret is worn out and is taking a short break. In a few minutes the ferret will usually engage the rear legs and inch forward by pushing with the hind feet only. Once rested or if teased by a playmate into resuming the fun, the ferret will jump up and again engage in full-blown play behavior. This slumping may stem from the silent stalking of polecat predatory-attack behavior in which the body is held close to the ground. The actual predatory attack in which the ferret springs forward may be elicited by any rapid movement, which initiates a preprogrammed electrical brain stimulation. Therefore further romping on the part of the domestic ferret play partner initiates a return-to-play assault by the “slumping” ferret.

Elimination Behaviors

Because of their high metabolic rate, short gastrointestinal tract, and gastrointestinal transit time of about 3 hours, ferrets defecate frequently and can mark the corners of their cages, much to the aggravation of the conscientious owner who keeps a clean litter box available at all times. It should be stressed that clean to the ferret often means unused, as many ferrets will avoid a litter box that has been soiled only once. Before defecating and urinating, ferrets will usually briefly explore their cage environment in order to find a suitable location in which to void. Most ferrets choose one or two corners within the cage as the favorite location.

Once satisfied with the spot, the ferret will turn around, back into the corner, and, with back slightly arched and tail raised directly over the back, defecate using slight pulsing contractions of the abdomen. Ferrets do not bury their stool but will at times perform a postdefecation anal drag in which they scoot their anus along the floor for a few seconds. When urinating the ferret behaves similarly to find the appropriate site, it then squats with the rear legs spread slightly apart. The urination posture of both males and females is similar, with the only difference being that females squat slightly lower. Ferrets have an innate love for digging, and a clean litter box is a perfect setting for digging and play behavior, often resulting in an unused, tipped-over litter box. See Box 4-1 for litter box tips.

BOX 4-1. Litter Box Tips.

-

♦

Spend some time observing your ferret's habits in the cage. When it backs into a cage corner to relieve itself, pick it up and place it in the corner of the litter box.

-

♦

Provide a large litter box that takes up most of the bottom of the cage. This is more likely to encourage use of the box. Punch holes in the litter box and wire it to the cage walls so that it can't be tipped over.

-

♦

Offer praise and food treats when your ferret uses the box.

-

♦

To discourage digging use newspaper strips in the litter box, and slowly add a little bit of litter. Over a week or more gradually add more litter and less newspaper. Most ferrets learn not to play in the litter fairly quickly. Newspaper doesn't deter odors, so it needs to be changed often.

-

♦

Buy a ferret-friendly litter box with one low side and a guard on the higher sides to prevent the ferret from backing up far enough to miss the box.

-

♦

Clean soiled corners, inside or outside the cage, with an appropriate pet odor neutralizer such as Urine-Off or Eliminodor.

-

♦

Provide litter boxes in corners of rooms ferrets are allowed to explore. More than one litter box is ideal. If your ferret seems to prefer a certain corner, place the litter box there.

-

♦

Ferrets do not bury their stool as cats do; therefore only a shallow layer of litter to cover the bottom of the litter box is needed. Avoid fine clumping litters as they are messy and dusty, potentially resulting in respiratory problems.

-

♦

Recycled newspaper litter or plain clay litter are good choices. Avoid scented litters, as ferrets may avoid them.

-

♦

Change the litter box(es) often to encourage use.

-

♦

Most ferrets won't soil their beds or food bowls. Place bedding or food dishes in all non–litter box corners of the cage. Bedding that has been slept in and retains the ferret's body scent works best.

-

♦

Before out-of-the-cage play, place your ferret in the cage's clean litter box. Continue to place it in the box until it urinates or defecates, then reward it with play.

Urine Licking Behaviors

It is not uncommon for ferret owners to report that their ferret licks or drinks its own or a cagemate's urine. Physical examinations and health workups including complete blood count, chemistry panel, and urinalysis are usually unremarkable. It is possible that this behavior stems from the behavior of polecat hobs, which sometimes groom themselves with their own urine to make themselves more desirable to jills.

Reproductive Behaviors

Ferrets usually reach sexual maturity at 8 to 12 months of age. Most reproductive behavior in the pet ferret is suppressed because of surgical sterilization and exposure to artificial, indoor lighting for consistent periods of time averaging 15 hours per day. Knowledge of normal reproductive behavior is important when interpreting certain ferret play and aggressive behaviors as well as understanding the behavioral and physiologic changes associated with adrenal disease.

Researchers have shown that both estrogen and testosterone contribute to masculine sexual behavior in male ferrets8 and female ferrets.41 Ferret hormonal activity is strongly influenced by endogenous circadian rhythms, which persist under conditions of constant light and constant darkness. However, these circadian rhythms are usually influenced by external factors such as light, temperature, barometric pressure, and hormones.20 Of these factors the most important is light, and ferret sexual behavior becomes more evident as natural day lengths increase. As day lengths increase, circulating melatonin levels diminish and hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released in a pulsatile fashion, in turn resulting in the release of pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which stimulate the release of estrogen and testosterone from the gonads.38 This results in an increase in sexual activity and interest.

Male Reproductive Behaviors

The onset of puberty in hobs is denoted by development of male sexual behaviors such as showing more interest in jills and the introduction of neck gripping and pelvic thrusting into their play behavior. If exposed only to natural lighting, the hob will become reproductively active a full 1 to 2 months before the jill.18 A testosterone surge will result in reproductive behaviors associated with attracting the opposite sex and protecting territory.

Hobs in rut will be more aggressive and will scent-mark in order to get the message across to potential breeding partners that they are ready to mate. Male ferrets have preputial gland secretions that they will wipe on objects by dragging their bellies across the ground. Perianal scent glands are also used for scent-marking by dragging the anus or scooting across the ground (anal drag). Numerous dermal sebaceous glands, most prominent at the nape of the neck, are used by rubbing and rolling onto inanimate objects hobs wish to mark. Males have more sebaceous glands than females, and glandular production appears to be under androgenic control.32 In a natural setting all these reproductive behaviors would allow multiple polecat hobs to stake their territory and fight off any potential competitive male suitors so that by the time the jill becomes sexually receptive they can get down to the business of breeding.

During the mount, the male grabs the nape of the jill's neck with his teeth and will grip her body by wrapping his forelegs around her ribcage. Pelvic thrusts last variable lengths of time up to 3 minutes. Between pelvic thrust bursts are periods of rest during which the male simply lies over the female and holds on with the neck grip. At the point of penetration the male will increase the arch of his back anteriorly, causing his foreleg grip to slip behind the female's rib cage.30 Holding this position for a variable but usually prolonged period of time is the best interpretation of penetration, at which time pelvic thrusting ceases. Occasionally the male will tense his pelvis, causing the tail to raise for short periods of time. At this time the female will occasionally flinch or remain flaccid.30

Variable mating times from 120 minutes to 3 hours have been reported, but in one study mating times recorded in 10 pairs of ferrets lasted from 34 to 172 minutes.30 These prolonged intromissions appear necessary in order to ensure fertilization. Whether this is to allow for increased sperm deposition as a result of the multiple ejaculations of the male or if it is necessary to stimulate the LH surge and subsequent ovulation in the female is open to debate. Neutered males with adrenal gland disease may display sexual behavior because of production of testosterone by the abnormal glands (see the discussion of adrenal disease).

Female Reproductive Behaviors

Behavioral changes associated with rising estrogen levels and puberty in the female ferret are less pronounced. Some jills may show evidence of being more excitable and nervous, whereas most show no behavioral changes at all. Wheel-running activity was shown to increase during estrus, with the number of wheel revolutions being doubled or tripled as compared with totals in ovariohysterectomized or anestrus ferrets.14 With the onset of full estrus, food intake may decrease and jills may sleep less and become irritable.18 Before onset of full estrus, jills will be unresponsive to the advances of a hob in rut. There will be a good bit of anal, genital, and neck sniffing, nose poking, and attempts by the male to grab the female by the neck, but the jill will ignore this behavioral foreplay or when tired of it hiss and nip or attack the male.

Dramatic edematous vulvar swelling in response to estrogen secretion by the ovaries is a clear signal that full estrus has occurred. At this time the jill will demonstrate the above behaviors but with more noise and intensity. These reproductive behaviors are very similar to those in other mammalian species, with much sniffing, genitalia display, and play fighting. When ready to breed, the female becomes flaccid and submissive, and mounting by the hob is allowed.

Being an induced ovulator, the jill will remain in estrus for extended periods if not bred. If breeding does not occur, the vulvar tissue will remain swollen, and hyperestrinism can cause severe anemia that will not abate until ovariohysterectomy or hormonal treatment is instituted. Adrenal disease may also cause a swollen vulva as a result of androgens being oversecreted by the adrenals. Remnants of ovarian tissue may also cause hyperestrinism.

Social and Antisocial Behaviors

As a general rule, patterns of behavior and social relationships are developed through learning as well as heredity, and social animal groups are organized by social status, territoriality, and reproductive activities. The interplay of experience and innate* factors in the development of behavior is very subtle and can be difficult to separate.16

European polecat kits are dependent on their mothers to bring them meat meals from the time they are weaned at 6 to 8 weeks to the time they begin to hunt on their own at 10 weeks of age. During this preweaning time kits have been observed to interact socially and play.24 However, by the time they are 13 weeks old, a time when kits may leave their nests permanently and go out on their own, kits show various degrees of independence from one another.24 Adult polecats are essentially solitary, with one study finding ferrets to share dens simultaneously with other ferrets on only 7.4% of 706 radio-tracking events.36 Also, adult ferrets demonstrate intrasexual territoriality, with dominant males showing more spatial overlap with females than with subordinate males.29

The domesticated ferret, on the other hand, shows much more diurnal activity, and many can be kept in pairs or groups without conflict. The best explanation for the difference in socialization patterns is that familiarization and habituation* play a significant role in the ferret's social response to both man and conspecifics. Familiarization in the form of imprinting may be involved as young polecats removed from their mothers during this critical phase in their development (4 to 10 weeks) become imprinted on their human caretakers. Evidence to support this belief is the fact that young polecats follow their mother on foraging expeditions and that hand-reared ferrets readily follow a human being. It has also been shown that the presence of the mother appears to facilitate the development of fear of humans in the young.34 In captivity, however, fear of humans does not develop in wild polecats if they are removed from their mother at any time before the second day after their eyes have opened (typically 28 to 34 days).34 Socialized ferrets are also more likely to show habituation than isolated ferrets,9 demonstrating that socialization and domestication go hand in hand. Pet ferrets acclimate to their environment and will rise to the occasion when given an opportunity to play, explore, or interact with others. In other words, they become diurnal as their periods of activity coincide with that of their human household.

Most ferrets enter the pet trade at any time from 6 to 10 weeks of age. In the United States most pet ferrets come from a few large commercial breeding farms and therefore are exposed to other ferrets and humans from the time their eyes open. From the above data, and from observing domestic ferrets and their obvious agreeable nature with both humans and cagemates, it seems safe to assume that ferrets, like dogs, do have a critical period of socialization. This period occurs between the time their eyes open at 4 weeks of age to 10 weeks.

Through their observations, most ferret researchers and multiple ferret owners believe that ferrets do not form any kind of social hierarchy and that positioning for dominance does not occur. Nevertheless, ferrets will fight occasionally, especially when exposed to an unfamiliar ferret. Some ferret rescue workers have recommended placing Ferretone on the necks and scruffs of all ferrets being introduced to an unfamiliar ferret. Ferrets consistently like this oily supplement and will likely lick each other in an appropriate manner while being less likely to demonstrate aggression.

Pet ferrets readily show affection for their human owners through gleeful greeting behavior and willingness to shower owners with ferret kisses. Young ferrets, on the other hand, are not likely to enjoy quiet cuddle time. Their exploratory behavior creates too strong an urge to get off an owner's lap and move on to investigate the environment around them. As ferrets mature, a combination of age, improved socialization, and a decrease in exploratory behavior results in a more staid ferret that enjoys periods of quiet snuggling and petting.

Ferrets have been domesticated for over 2000 years; therefore it seems likely that given the right environment, poorly socialized ferrets can become more affable and gregarious. This suggestion is supported by the fact that intact hobs kept together in a colony situation with minimal human handling can live in harmony outside the breeding season.

Grooming Behaviors

Ferrets will groom their fur through licking and gentle nibbling motions. They normally maintain a smooth and shiny hair coat as long as they are kept on a balanced diet made up primarily of high-quality animal protein and fat. Ferrets have also been known to groom other ferrets to which they are bonded. This grooming is usually around a cagemate's ears and head as the ferrets lie side by side.

Normal ferret skin is smooth and pale without evidence of flaking, scabs, or inflammation. A dry, dull fur coat and evidence of flaking may be a reflection of poor diet or low environmental humidity. In the wild ferrets spend a good part of the day in underground burrows in which the humidity is high and the temperature a consistent 55° F (13°C). The dry warmth of many homes during the winter months may cause the skin to dehydrate, with subsequent flaking and itching. Pruritus may also be a sign of external parasites or adrenal disease.

A ferret's hair coat has a thick cream-colored undercoat covered by longer, coarse guard hairs. It is the color of these guard hairs that defines the various ferret coat colorations—from dark and light sable to cinnamon, silver, or white. Both intact and neutered ferrets undergo a hormonally influenced molt, usually twice a year, in which the hair coat thins in response to photoperiod. As daylight hours and environmental temperatures increase, corresponding with late spring in the Northern Hemisphere as well as ferret breeding season, ferrets may lose most of their guard hairs over a period of several weeks. Ferrets can get trichobezoars from grooming, which can get large enough to cause gastric obstruction or irritation (Figure 4-7 ). Therefore the use of a hairball remedy in the form of a feline petroleum-based laxative is especially important during this seasonal molt.

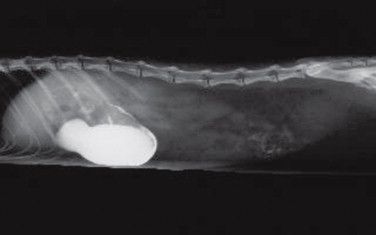

Figure 4-7.

This lateral abdominal radiograph was taken 90 minutes after the ferret was given barium. The ferret had a trichobezoar causing a gastric blockage secondary to grooming during molt. As daylight hours and environmental temperatures increase, corresponding with late spring in the Northern Hemisphere and the ferret breeding season, ferrets may lose most of their guard hairs over a period of several weeks. The use of a hairball remedy in the form of a feline petroleum-based laxative is especially important during this seasonal molt.

(Courtesy Peter Fisher.)

The skin of the ferret contains numerous sebaceous glands, the secretions of which give the ferret its characteristic musky odor.32 These secretions also are strongly influenced by seasonal hormonal influences, especially in the male, and may give the coat a greasy feel and an obvious yellow to orange appearance most noticeable over the dorsal shoulder area. In the Northern Hemisphere these secretions are observable in the late spring to early summer, corresponding with the ferret's natural breeding season. If this coat discoloration and increased odor are particularly evident and do not diminish with time, they may be signs of adrenal disease, especially in the male ferret. If associated with adrenal disease, loss of guard hairs may occur concurrently, and areas of obvious alopecia may develop, as well as other systemic signs discussed elsewhere. During this time ferrets may also show increased scent-marking behavior and will rub their backs and shoulders along carpet and furniture to the dismay of odor-conscious owners. Cage walls and bedding readily take on the yellow color and musky odor of these sebaceous secretions.

Feeding Behaviors

The ferret is an obligate carnivore with a short intestinal tract that lacks a cecum and ileocolic valve. The small intestine is approximately five times longer than the ferret's body, and the mean gastrointestinal transit time of food passage from stomach to rectum is 182 minutes.3 This rapid transit time, along with the ferret's lack of intestinal brush border enzymes, especially lactase, contributes to inefficiency in absorption. As a result, they are less able than cats to absorb sufficient calories from carbohydrates. To compensate for the inefficiency of its digestive tract, the ferret requires a concentrated diet, high in protein and fat and low in fiber.

Ferrets snack and eat multiple small meals throughout the day, and unless regularly fed very high–fat content foods they generally eat as much as they want without becoming obese. Ferrets normally increase food intake approximately 30% in the winter and gain weight by depositing subcutaneous fat. This will reverse as daylight lengthens in the spring. For maintenance, ferrets may consume 200 to 300 kcal/kg body weight daily. Daily food consumption averages 42 g (1.5 oz) and 49 g (1.7 oz) dry matter per kg body weight for male and female ferrets, respectively.4

Ferrets are solitary feeders that when allowed free access to food will eat 9 or 10 meals per day, which is true of most species when food is available ad libitum. In laboratory studies in which ferrets had to perform a task (bar press) to gain access to food, it was shown that meal frequency declined.21 There was a corresponding increase in meal size, allowing the ferrets to maintain a relatively constant total daily food intake sufficient to maintain normal growth and body weight.

These shifts in feeding patterns in response to increased work needed to procure a meal are similar to those in other species and are consistent with an ecologic analysis of foraging behavior.21 Generally, socially feeding animals increase procurement and consumption rates as food availability decreases, whereas solitary feeders, such as cats and ferrets, do not.27 This study demonstrates that ferrets could be maintained on meals fed once or twice daily versus a free-feeding situation. Many ferret owners like to offer raisins or other simple carbohydrates as treats, but these high-sugar treats are difficult for the ferret's gastrointestinal tract to digest and may be contraindicated because of the prevalence of insulinoma in ferrets. Instead, small pieces of cooked chicken, Totally Ferret, or N-Bones treats may be offered.

Prey-Catching Behaviors

The predatory behavior of ferrets consists mainly of instinctive behavior patterns that are elicited by external stimuli. In all higher animals a sudden change or stimulation will usually elicit a movement toward the source—a response described as the orientation response. The learning of an orientational component plays an important role in the development of functional sequences of behavior. Eibl-Eibesfeldt observed the prey-catching techniques of polecats and found that the normal movements of pursuit, grasping the neck of the prey, shaking it, and turning it over on its back occur the first time an appropriate object is presented.19 After several experiences the neck bite becomes properly oriented for quick killing of prey. More recently, similar behavior was demonstrated in the black-footed ferret in which maturation, experience, and greater environmental complexity (enriched cage, including encouragement of food-searching behaviors) all increased the likelihood of the ferret's making a successful kill.44

This behavior becomes important when the domestic ferret is kept in a household with other exotic pets that it may perceive as prey. It is at this time that the ferret may cross the line from play behavior to prey-catching behavior. Both behaviors can look similar initially, as ferrets at play also demonstrate neck biting, but if stimulated by a perceived prey species (pet bird, lizard, or rodent) the ferret may instinctively go beyond play and inflict harmful or fatal bite wounds on the other pet. Therefore, ferrets should not be left unsupervised with other small exotic pets.

Apfelbach showed that for the ferret the time needed to catch and kill rats depended on the size of the rats in relation to the ferret. Killing success decreases with a relative increase in prey size.2 This may explain why the domestic ferret tends to live harmoniously in a home with dogs and cats. These larger species do not stimulate instinctive prey catching and killing behavior, but instead the response to the larger animal takes the form of the less-intense, albeit similar, play behavior.

Exploratory Behaviors

A number of investigations have demonstrated the existence in mammals of behavior not motivated by fear, thirst, or hunger and unrelated to general activity level. These have led to postulation of another drive, the exploratory drive.15 Characteristically, such behavior is aroused by novel external stimulation. It involves either locomotor activity or manipulation of objects, and it declines as a function of time.15 In general, higher animals will approach and examine strange objects with whatever sensory equipment is available to them, and in a strange environment they usually move around and examine all of their surroundings.

When an animal is exposed to a novel object or environment it will first familiarize itself with the new stimulus or situation. With a strange object, exploration must precede play. As familiarity increases the exploratory behavior decreases and the animal's curiosity of the novelty may with time lead to play behavior. With other new situations fear may lead to rejection instead of exploration. Whether fear or curiosity and subsequent play behavior are elicited depends on various factors, including the physiologic state of the individual animal and the magnitude, intensity, or strangeness of the eliciting stimulus. In general, a small change in the environment elicits investigation, whereas a major change may elicit fear.

Degree of domestication can also affect exploration behavior. In his work on identifying behavioral differences between the domesticated ferret and its wild counterpart, the European polecat, Poole (1972) showed that wild ferrets are less likely to examine and more likely to avoid strange objects than tame ferrets.34 In this study attention responsiveness to new auditory stimuli was measured, and exploration of new surroundings was observed. The attention response is essentially a method of scanning for stimuli. The European polecat shows extreme caution in exploring an unfamiliar environment; it takes frequent cover, uses definite pathways in the immediate vicinity of its den, and regularly returns to its home area after making forays into unfamiliar territory. The polecat also shows a more rapidly diminished attention response to auditory stimuli.

The domestic ferret, on the other hand, can be moved to a strange cage or placed in an unfamiliar area without showing signs of fear or disorientation. The ferret also shows persistent response to repeated auditory stimuli, a feature that might also be related to the reactivity typical of a juvenile animal. These results again appear to support Lorenz's view that domesticated animals show more juvenile behavior as compared with their wild counterparts.19 Ehrlich's work with the black-footed ferret15 demonstrated similar findings: increased handling (equivalent to greater degree of domestication) leads to increased exploration behavior. Those findings may explain why today's domestic ferret shows an intense curiosity and little fear of its surroundings. When allowed to roam, the domestic ferret shows fearless exploratory behavior: Box on the floor? Got to see what's in it. Hole in the floorboard by dishwasher? Got to go inside and explore. Cabinet door ajar? Got to open it and explore what's inside. Any open door or unexplored space is an invitation for scrutiny.

The domestication process has been thorough at removing the ferret's fear response when it comes to exploratory behavior, and the ferret's inquisitive nature and love of exploration are boundless, sometimes to its detriment. As a result of being continuously handled and carried securely without being dropped, or perhaps because of its reportedly poor eyesight, domestic ferrets show little fear of height. This is opposite to what Shimbo39 found in her personal experience with undomesticated polecats, which appeared very frightened and uneasy when exposed to heights.39 This apparent lack of fear of heights in the domestic ferret can result in injuries or death if they climb out of an upstairs or apartment window. An open door may also be addressed with fearless curiosity, and the urge to explore can lead the ferret to the outdoors where it is limited in its ability to find food and to protect itself from predators or from extremes of weather.

Play Behaviors

Reflecting on the 1953 Lorenz hypothesis that the behavior of domestic animals resembles that of juvenile individuals of their wild counterparts,19 it can certainly be said that this holds true when it comes to play behavior. In general, motor patterns used in intraspecies play behavior are characterized by actions that occur frequently in other functional contexts (e.g., aggression, sexual, and predatory behaviors).

In 1966 Poole observed polecats (Putorius putorius) at play and demonstrated the incomplete sequence of conflict behavior. Four of the agonistic patterns were absent from intense play behavior—two extreme forms of attack (“sustained neck biting” and “sideways attack”) and two extreme fear patterns (“defensive threat” and “screaming”).19 The play behavior imitated patterns of aggression, but in a less-serious and less-threatening manner. Adolescent ferrets' play behavior also imitates sexual behavior, with juvenile male ferrets exhibiting higher levels of neck biting and “stand-over” behavior than females (Figure 4-8 ). Sex differences in the expression of prepubertal play behavior of ferrets apparently result from the differential exposure of males and females to androgen during the postnatal period.42

Figure 4-8.

Mounting play behavior. Adolescent ferrets' play behavior also imitates sexual behavior, with juvenile male ferrets exhibiting higher levels of neck biting and “stand-over” behavior than females. Sex differences in the expression of prepubertal play behavior of ferrets apparently result from the differential exposure of males and females to androgen during the postnatal period.

(Courtesy Peter Fisher.)

The same holds true for the domestic ferret. The ferret demonstrates an obvious love of play in a variety of forms, and we can imagine their merriment stemming from predatory, sexual, exploratory, and digging behaviors. The typical sequence for two ferrets at play would begin with the chase, followed by an exaggerated approach or ambush, veering off, and reciprocal chasing, followed by mounting, rolling, and wrestling with inhibited neck biting (Figure 4-9 ). These mock sexual and predatory behaviors are accompanied by vocalizations that signal both excitement (dooking) and anger (hissing).

Figure 4-9.

Neck-biting play behavior. The typical sequence for two ferrets at play would begin with the chase, followed by an exaggerated approach or ambush, veering off, and reciprocal chasing, followed by mounting, rolling, and wrestling with inhibited neck biting. These mock sexual and predatory behaviors may be accompanied by vocalizations that signal both excitement (dooking) and anger (hissing).

(Courtesy Peter Fisher.)

The solitary ferret at play also demonstrates various behaviors that stem from normal behaviors seen in its wild counterpart. Predators stalk and chase quarry. Observe the ferret playing with a hard rubber ball or squeaky toy, and you will see the same type of behaviors. Hard rubber balls, such as Super Balls, really stimulate hunt and capture behavior. A rolling or bouncing ball captivates the ferret, which immediately begins the hunt. The ball is aggressively pursued until the ferret “captures” it by grabbing it, then bites hard and shakes it as if it were prey. Keep in mind that ferrets love soft-rubber items and will readily ingest the torn pieces of soft rubber, creating potential for gastrointestinal foreign bodies (Figure 4-10 ). Therefore any ferret play ball needs to be hard enough and large enough that the ferret cannot readily tear off chunks that it might ingest (Figure 4-11 ).

Figure 4-10.

Ferrets, especially young ones, love to chew and will eat things that are inappropriate for them and may cause gastrointestinal obstruction. They are especially fond of plastic, rubber, and foam rubber

(Courtesy Teresa Bradley Bays.)

Figure 4-11.

Rubber ball play. A rolling or bouncing ball captivates the ferret, which immediately begins the hunt. The ball is aggressively pursued until the ferret “captures” it by grabbing it, then bites hard and shakes it as if it were prey.

(Courtesy Peter Fisher.)

Playing ferrets also love to dig. This digging behavior comes naturally, as the sharp claws and streamlined body of the polecat were designed for digging and tunneling deep underground in pursuit of game or for making their below-ground burrows. This ancestral behavior may explain why ferrets love to dig at the carpet, the floor, and their litter box and enjoy digging in the soil of potted plants. Some ferret owners satisfy this desire to dig by allowing the ferrets to dig away in a large plastic play box (such as a large cat litter box) filled two-thirds full with rice or potting soil. A neater option is to provide the ferret with tubing to explore. Both flexible (ribbed plastic similar to clothes dryer vent tubing) and rigid (PVC pipe) tubing make for great exploratory amusements.

Because of its keen olfactory sense the ferret explores with its nose. The ferret can be observed searching back and forth across a room with its nose to the ground. When it finds an object of interest, often the ferret will drag it off to its “lair,” also known as “ferreting it away” (Figure 4-12 ). This ferret burrow is usually the most inaccessible location the ferret can find—a small cubby or a hole discovered under the kitchen cabinets or in the back of a closet. The ferret is instinctively seeking out a tight, dark, enclosed space, which mimics its native ancestor's underground burrow. It is amazing to see the variety of objects the ferret has “stolen and stashed.” This hoarding behavior probably stems, once again, from behaviors seen in polecats, which have a very high metabolic rate and energy need; therefore having a readily available food supply is a must. Instead of toys and objects of interest, polecats would build a cache of leftover food items and prey on which to feed while resting in their burrows.

Figure 4-12.

Hiding objects. When it finds an object of interest, often the ferret will drag it off to its “lair,” also known as “ferreting it away.” This ferret burrow is usually the most inaccessible location the ferret can find—a small cubby or a hole discovered under the kitchen cabinets or in the back of a closet.

(Courtesy Peter Fisher.)

Environmental Enrichment

Studies suggest that environmental impoverishment, whether in the form of physical or social restriction or limitation of play objects, has wide-ranging effects on the overall well-being of ferrets. Chivers and Einon9 found that some of the isolation-induced effects on behavior seen in rats also occurred in ferrets, with deprivation of rough and tumble social play causing hyperactivity that persisted into adulthood.23 Work done by Korhonen (1992) showed that overall health, reflected by optimum weight and fur coat quality, occurred when ferrets were provided with increased housing floor space and compatible cagemates and when offered balls and bite cups with which to play.23

Although adult ferrets may appear perfectly content sleeping in their hammocks 20 hours a day, this certainly is not mentally and physically stimulating. Unsupervised free time in a “ferret proof” room is always recommended. Keep in mind that ferrets love human interaction, like to explore new places and objects, have a keen olfactory sense, and enjoy digging. A ferret that jumps back and forth in front of you and nips at your feet is telling you it wants to play. Simply getting down on your hands and knees and chasing a ferret will stimulate more ferret dancing and happy vocalizations, chuckling, or dooking.

If the ferret is not prone to biting, try playing tug-of-war games with an old washcloth or favorite plush toy (Figure 4-13 ). If the ferret is other-ferret friendly, try taking it to a fellow ferret fancier's ferret-proofed home for some exposure to a whole new environment complete with sights, smells, and ferret friends. Transmissible diseases, especially the gastrointestinal infection likely caused by a coronavirus and commonly referred to as epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE), should be considered when allowing initial contact between ferrets.

Figure 4-13.

Environmental enrichment. Fuzzy plush toys on an elastic string make a great play toy that keeps the playful ferret entertained. Play with these types of toys should be supervised.

(Courtesy Lisa Leidig.)

Digging can be encouraged by hiding toys in a children's sandbox or in a litter box (Figure 4-14 ). Remember, however, to never leave ferrets unsupervised outdoors, as they tend to wander and may get lost. They are also relatively intolerant of extreme heat or cold.

Figure 4-14.

Environmental enrichment. Filling a large plastic litter box with recycled newspaper pellets or rice and hiding objects for the ferret to find helps satisfy their innate digging behavior. Ferrets that enjoy playing in their water bowls will also enjoy recreation in a small wading pool with added Ping-Pong balls coated with Ferretone.

(Courtesy Peter Fisher.)

Inactive ferrets are prone to weight gain and its subsequent effects on overall health. Constant captivity in an enclosed space may also lead to behavioral problems such as biting and conspecific aggression. It is the ferret owner's responsibility to ensure that this active, energetic pet's mental, physical, and sensory well-being is routinely stimulated so that it may lead a full and robust life. Not all activities require human interaction, nor do they require a big monetary investment. Many just require a little time, creativity, and imagination. Box 4-2 describes some activities created by ferret owners—suggestions for inexpensively creating a fun and stimulating ferret household environment.

BOX 4-2. Environmental Enrichment Ideas.

-

♦Use food as treats, with the following caveats. Keep in mind that ferrets are strict carnivores with high protein requirements. They use fats more so than carbohydrates for energy needs. However, excessive high-fat treats will result in the ferret's caloric needs being met with minimal food intake and as a result protein requirements may not be met. So if treating with high-fat oils such as Ferretone, remember to use them in small quantities.

-

•Try rubbing a little Ferretone on Ping-Pong balls and floating them in a shallow pan of water.

-

•Place a few pieces of food or desirable treat in an egg carton, tape the lid shut and cut a small hole in the top. Make the ferret work for the treat. The same idea can be used with a milk carton.

-

•Place a few pieces of good-quality ferret food (try a different variety from its normal everyday food) in an 8-ounce (237 mL) plastic soft-drink bottle, leave the top off, and let the ferret roll and play with it trying to make the treats come out.

-

•

-

♦Create handmade toys and amusement centers.

-

•Make tunnels from PCV pipe or empty oatmeal containers with the bottoms cut out and taped end to end.

-

•Tape cardboard boxes together, and cut holes in various locations for exploration.

-

•Glue a small bell inside a plastic Easter egg.

-

•Make a ferret maze out of a large appliance box. Fill the box with scrap cardboard rolled and taped into round or triangular tubes. Hide food items at various spots within the box.

-

•

-

♦

Fill a box with potting soil, rice, hay, plastic balls, or crumpled paper balls, and let the ferret fulfill its instinctive digging needs.

-

♦

Use old towels to give a ferret a “magic carpet ride,” or just twirl the towel around and over the ferret.

-

♦

Use dryer hose to satisfy instinctive tunneling behavior. Some owners like to stretch the hose out, using a beanbag chair to hold one end in place.

-

♦

Obtain a bottle of deer or boar scent from the hunting section of a sporting goods store, and rub a drop or two on a favorite toy.

-

♦

Tie plastic or a Ping-Pong ball to a piece of sturdy string and hang it from the ceiling to 2 in (5 cm) above the ground.

-

♦

Put empty paper grocery bags on the floor. Some of the bags can be filled with crumpled paper, Ping-Pong balls, or food treats.

Aggressive Behaviors

Conspecific Aggression

The primary function of aggressive behavior between conspecifics is to determine and maintain rank or territory. Aggressive actions are among the most prominent social activities of animals, with patterns of aggressive behavior differing from species to species. Although such actions often appear antisocial, the fighting, bluffing, and threatening serves to promote survival of the species. It appears that a species disposition to aggression is innate, but many details of the aggressive behavior are learned or perfected through experience.12

In most animals early social experience greatly affects subsequent aggressive behavior. True fighting behavior between domestic ferrets is similar to that described by Poole in his study of European polecats33—as an incident during which each animal attempted to bite the back of its opponent's neck with a sustained, immobilizing hold. Successful bites (i.e., those during which the opponent was unable to break free) were sometimes accompanied by shaking or dragging of the immobilized animal. When the attacked animal was able to break free, it sometimes displayed evidence of intimidation, including screaming, defensive biting, hissing, fleeing, urinating, or defecating. However, serious injury did not usually occur.40

Staton and Crowell-Davis40 reported on the results of an experimental protocol to evaluate the effects of four factors on the fighting behavior between pairs of domestic ferrets: familiarity (pairings of cagemates versus strangers); time of year (pairings during winter versus spring); sex (male-male, male-female, and female-female pairings); and neutering status (intact-intact, neutered-intact, and neutered-neutered pairings).40 Awareness of factors that might affect the potential for aggression between unfamiliar ferrets may predict likelihood of a fight. Results of the Staton and Crowell-Davis study suggest that familiarity, sex, and neutering status are all important determinantes of aggression between ferrets. Sixty percent of the attempts of pairing strangers resulted in combative behavior, whereas none of the familiar cagemates fought.

Based on previous information on aggressive behavior in intact male ferrets33 and that shown in studies of other species, it was thought that intact male ferrets would, in general, be more aggressive than neutered animals. However, the study showed that intact male ferrets were not indiscriminantly aggressive and that pairs of neutered males were just as likely as pairs of intact males to fight. In addition, the study showed that females were in general not less aggressive than males, with pairings of unfamiliar neutered female ferrets likely to result in aggression. The study also showed that if unfamiliar neutered ferrets are introduced, the pairing of two males or a male and female would result in the lowest levels of aggression.

It is also interesting to note that time of year (winter versus spring) did not affect the incidence of fighting behavior, even for intact animals in which circulating hormone concentrations are likely to change with seasons. This may have been a result of the fact that animals in this study were housed under artificial lighting and that this amount of light was not altered to mimic the increase in daylight that stimulates the breeding season in ferrets. The fact that 60% of unfamiliar pairings did fight illustrates the difficulties faced by pet owners attempting to introduce a new ferret into the household or in ferret shelters in which new additions and limited space result in frequent pairings of strange ferrets.

Studies with kangaroo rats, pigs, and mice have shown that olfactory exposure, visual exposure, and sharing a common substrate may all play a key role in establishing familiarity between strangers and thus reduce fighting behavior.40 A second part of the Staton and Crowell-Davis study showed that this was not the case with ferrets. Housing strange ferrets next to each other for 2 weeks where they shared visual and olfactory stimuli did not reduce fighting when the ferrets were later introduced. However, ferret owners claim that housing a new ferret next to an existing ferret or ferrets for a period of time before introduction does help. If introducing a female to a bonded male-female pair, experienced ferret owners advocate housing the new female with the male for a few days, as they are more likely to get along. If they get along, then putting all three together inside the original cage with additional sleeping arrangements can be tried. Make sure close supervision is provided during these introductory periods.

In addition, ferret shelter managers have found that a 4- to 5-day introductory period works best when familiarizing a new ferret to a multiple-ferret household. A small open room with a minimum of hiding areas and one that does not house other ferrets works best as a neutral meeting site. The new ferret member is introduced to the most congenial ferret in the household, usually an older, easygoing male, for 30 minutes of chaperoned meet-and-greet time. If the ferrets seem to get along, then the time together is extended. Once the new ferret has accepted the introductory ferret, other ferrets are slowly introduced to see if the new ferret is capable of cohabiting with the group. Ferrets are individuals, and this bonding procedure does not always work; some ferrets just prefer living alone.

Aggression and Biting Behaviors

Ferrets use their mouths in many behaviors, including play, attention seeking, defense, “hunting,” fear, and response to pain. Watch young kits wrestle and play and you will see them bite each other's necks and drag each other around while grasping any loose skin with their mouths. Mother ferrets use their mouths to pick up and move their kits if they have wandered too far and to discipline them with gentle nips. Ferrets playing with a toy will usually pick it up, grab it, and drag it around with their mouths.

Inappropriate nipping or biting may occur when ferrets perceive people as playmates, as an attention-getting device, or when ferrets are in pain or hungry. Depending on the message they are trying to convey, ferrets may give a friendly nip or grab a human's hand or foot, bite down, hold on, and shake their heads. This is how they would respond to another ferret, whose naturally thick skin and fur would lessen the intensity of the bite. To humans, however, the bite can be both painful and alarming.

In ferrets with a history of consistent biting behavior, it is ideal to try to determine the cause. This begins with collecting a behavioral history and in problem cases having the owners fill out a behavioral questionnaire (Box 4-3 ). Once the type(s) of aggression and most probable causes for the aggression have been identified, the goal is to avoid situations that elicit the biting behavior and to diminish biting behavior if it occurs.

BOX 4-3. Behavioral Questionnaire for the Biting Ferret.

-

♦

How long have you owned your ferret?

-

♦

Are there certain situations that initiate the biting behavior?

-

♦

Is this your first pet ferret?

-

♦

Describe your ferret's environment?

-

♦

Is there a new pet in the household?

-

♦

Has the amount of “free time” and exercise your ferret gets recently changed?

-

♦

Have there been any lifestyle changes that may be reflected in the ferret's behavior?

-

♦

Have you experienced a recent move or change in living arrangements?

-

♦

Have any new ferrets been brought into the household?

-

♦

Do young children routinely handle your ferret?

-

♦

What do you do when your ferret bites?

-

♦

What forms of behavior modification have you tried? What is the response?

-

♦

Are there situations or objects that stimulate biting behavior?

-

♦

Do you smoke?

-

♦

Do you apply hand cream to which the ferret may be attracted?

Box 4-4 summarizes the various causes of ferret aggression and potential situations in which biting behavior may occur. Recently purchased or adopted ferrets may be especially problematic, as they come with limited socialization, training, or handling. These (often young) ferrets may bite as a fear response to sudden movements and noise. This is probably a reflex response that stems from the ferret's wild counterparts who were preyed on by larger mammals or birds of prey. If frightened or startled the ferret may show a defense reaction much like the frightened submissive dog—it will arch the back and fluff out the tail and body fur (piloerection) to look larger and stronger, open the mouth in a threatening way, and hiss or screech in order to frighten the perceived attacker or alarm other ferrets in the area. If not descented the ferret may empty or express its anal sacs, again much as a frightened dog would do. Depending on the level of socialization of the ferret, this fear response may also lead to biting.

BOX 4-4. Causes of Ferret Aggression or Biting Behavior.

-

♦

Play aggression—The most common underlying cause for biting in ferrets, this is a normal behavior, especially in young ferrets, that needs to be mitigated.

-

♦

Possessive aggression—Aggressive behavior directed at humans or other pets that approach the ferret when it is in possession of something it values, usually a favorite toy. May be exacerbated by restricting the ferret's free time and space.

-

♦

Fear-related aggression—Occurs when ferret is startled or poorly socialized and not used to handling. This type of aggression can occur as a result of punishment, traumatic experiences, or genetic factors.

-

♦

Predatory aggression—A normal innate behavior of the polecat from which the ferret was domesticated. When directed toward people or other pets it results in a behavioral problem that may involve stalking, chasing, grasping, and biting.

-

♦

Redirected aggression—Occurs when the harmful behavior is directed toward a person or pet that is not the original stimulus for the aggressive behavior. Occurs when a person or pet interferes with two ferrets that are playing hard.

-

♦

Maternal aggression—Refers to aggressive behavior directed toward humans or other pets that approach a jill with her kits.

-

♦Pain-induced or irritable aggression—Caused by an underlying medical condition:

-

•Gastrointestinal foreign body, hairball, gastric ulcers

-

•Inflammatory bowel disease

-

•Hormonal changes associated with adrenal disease

-

•Any painful disease process

-

•

-

♦

Sexual aggression—May explain conspecific ferret aggression in which mating behavior may be accompanied by intense biting.

It is best to try and prevent this defense response by letting the fearful ferret know your whereabouts and intentions when handling. To ensure that the ferret will not be startled, make noise outside the cage or rattle the cage door so they are aware of your presence, and when approaching talk in a soothing manner. If the ferret continues to appear fearful, give it time to adjust to your presence before handling, then use a towel to pick it up while talking to it quietly.

If a ferret is possessive of a particular toy, take away the guarded object, and discourage the ferret from obtaining objects that are off limits. If the problem persists, try redirecting the ferret's attention with an alternative activity such as ball chasing, or try desensitizing the possessive ferret with repeated relaxed exposures to the object or toy and reward with gentle praise or a treat when the ferret is not possessive. Be careful not to reinforce this behavior by offering another, possibly more acceptable toy while the ferret is nipping.

With fear-related or maternal aggression, avoid circumstances that might elicit aggression. It is important not to startle or grab fearful ferrets, especially when they are sleeping, and to respect a nursing jill's privacy and innate protective behavior. Ferrets are rarely fearful once they are awake and aware of your presence; however, if they continue to be cautious and nippy, try to replace the fear response with a counteraction such as anticipation of play or food. Extra care should be taken with deaf ferrets that may startle more readily. Congenital deafness occurs in ferrets, and anecdotal reports indicate that an increased incidence of deafness exists in albino and/or black-eyed ferrets.

If a ferret stalks and nips at young children, it may be best to change your ferret's free time to a time when the child is napping or away from home. Owners should be made aware that other household pets (e.g., birds, rabbits, or rodents) may be perceived as prey, and unsupervised contact time with that pet should be discouraged. It is also a good idea to put the pet dog or cat in another room during the ferret's free time until the behavioral interaction of these pets is known.

Overly exuberant play behavior or play aggression is the most common situation in which ferret frolicking can lead to biting. Gentle nips are normal and natural to ferrets, which often bite at other ferrets to encourage play. Therefore it is not uncommon for ferrets to nip their owners gently in order to gain their attention. Play biting in ferrets is similar to the same misbehavior in puppies. Box 4-5 outlines ideas for controlling this behavior problem.

BOX 4-5. Preventing and Managing Ferret Play Biting Behavior.

-

♦

Avoid aggressive play (pushing, rolling, wrestling).

-

♦

Avoid tug-of-war games.

-

♦

Keep fingers curled when playing with an easily excited ferret.

-

♦

Use time outs—10 to 15 minutes in a small room or pet carrier (do not use ferret's cage for time out) with no toys or towels or anything with which the ferret could play.

-

♦

When the ferret bites, make a high-pitched sound (yip, ouch). This will mimic the sound another ferret makes when play behavior gets out of hand.

-

♦

When the ferret starts biting during play, redirect it to appropriate toys such as hard rubber balls or plush toys.

-

♦

Try a gentle scruffing, and wiggle the ferret in the air while making a hissing sound (this is how a mother ferret disciplines a kit), but be mindful that the ferret may get even more excited.

-

♦

Display gentle but firm dominance over the ferret by holding it on its back for a few minutes.

-

♦

Wrap the ferret snugly in a towel or baby blanket so that it cannot get out and bite. Walk around while gently cuddling and talking to the ferret and petting when it is calm. Offer a food treat when the ferret remains calm.

Ferret play can escalate to the point where its frenzied commotion borders on aggressive behavior. One ferret may arch its neck and back and shove itself sidelong into the other in a very characteristic way. This fake challenge is an example of subdued or “domesticated” aggressive behavior turned to play. Nose poking, ramming another ferret with mouth open, and defensive threats in which the ferret stands very erect with back arched and tail possibly brushed up are other examples of playful behaviors that originate in polecat aggressive behavior. The magnitude of the actions and vocalizations differentiates play from aggressive behavior.

Young kits at play are particularly mouthy, as seen with continual biting, mouthing, tugging, and dragging each other. These behaviors are believed to reflect innate dominance behavior learning.6 Similar to other mammals, a mother ferret will tug and pull at her young as a means of discipline and control. If kits are sold to pet retailers at a young age (some kits are placed in pet shops as early as 6 weeks of age), mother-kit socialization patterns may be disrupted. This lack of maternal nurturing can lead to overly stormy play behavior, which may be perceived as aggression by new owners.