Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors (rAAVs), based on AAV8 and AAVrh.10, have been utilized in multiple clinical trials to treat different monogenetic diseases. The closely related AAVrh.39 has also shown promise in vivo. As recently attained for other AAV biologics, e.g., Luxturna and Zolgensma, based on AAV2 and AAV9, respectively, the vectors in this study will likely gain U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for commercialization in the near future. This study characterized the capsid structures of these clinical vectors at atomic resolution using cryo-electron microscopy and image reconstruction for comparative analysis. The analysis suggested two key residues, S269 and N472, as determinants of BBB crossing for AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39, a feature utilized for central nervous system delivery of therapeutic genes. The structure information thus provides a platform for engineering to improve receptor retargeting or tissue specificity. These are important challenges in the field that need attention. Capsid structure information also provides knowledge potentially applicable for regulatory product approval.

KEYWORDS: AAV, DNA packaging, adeno-associated virus, blood-brain barrier, capsid, cryo-EM

ABSTRACT

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) from clade E are often used as vectors in gene delivery applications. This clade includes rhesus isolate 10 (AAVrh.10) and 39 (AAVrh.39) which, unlike representative AAV8, are capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), thereby enabling the delivery of therapeutic genes to the central nervous system. Here, the capsid structures of AAV8, AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 have been determined by cryo-electron microscopy and three-dimensional image reconstruction to 3.08-, 2.75-, and 3.39-Å resolution, respectively, to enable a direct structural comparison. AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 are 98% identical in amino acid sequence but only ∼93.5% identical to AAV8. However, the capsid structures of all three viruses are similar, with only minor differences observed in the previously described surface variable regions, suggesting that specific residues S269 and N472, absent in AAV8, may confer the ability to cross the BBB in AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39. Head-to-head comparison of empty and genome-containing particles showed DNA ordered in the previously described nucleotide-binding pocket, supporting the suggested role of this pocket in DNA packaging for the Dependoparvovirus. The structural characterization of these viruses provides a platform for future vector engineering efforts toward improved gene delivery success with respect to specific tissue targeting, transduction efficiency, antigenicity, or receptor retargeting.

IMPORTANCE Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors (rAAVs), based on AAV8 and AAVrh.10, have been utilized in multiple clinical trials to treat different monogenetic diseases. The closely related AAVrh.39 has also shown promise in vivo. As recently attained for other AAV biologics, e.g., Luxturna and Zolgensma, based on AAV2 and AAV9, respectively, the vectors in this study will likely gain U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for commercialization in the near future. This study characterized the capsid structures of these clinical vectors at atomic resolution using cryo-electron microscopy and image reconstruction for comparative analysis. The analysis suggested two key residues, S269 and N472, as determinants of BBB crossing for AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39, a feature utilized for central nervous system delivery of therapeutic genes. The structure information thus provides a platform for engineering to improve receptor retargeting or tissue specificity. These are important challenges in the field that need attention. Capsid structure information also provides knowledge potentially applicable for regulatory product approval.

INTRODUCTION

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are nonpathogenic, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses of the Parvoviridae used as vectors for gene delivery applications. To date, three AAV-vector-mediated gene therapies have gained approval for commercialization: Glybera, an AAV1 vector for the treatment of lipoprotein lipase deficiency by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (1); Luxturna, an AAV2 vector for the treatment of Leber’s congenital amaurosis (2); and Zolgensma, an AAV9 vector for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (3), the latter two by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These approvals usher in a new era for the use of this vector system for the treatment of monogenetic diseases. The virions of these viruses are composed of nonenveloped capsids with T=1 icosahedral symmetry and diameters of ∼260 Å that enclose the ssDNA genome (4). Currently, 13 human and primate AAV serotypes, and numerous additional genomic isolates from different primate and nonprimate species, have been described (5–7). The amino acid sequence identity of the capsids of these different AAVs can diverge up ∼50%. The capsids are assembled from 60 subunits of three overlapping capsid viral proteins (VPs)—VP1 (∼82 kDa), VP2 (∼73 kDa), and VP3 (∼61 kDa)—in a 1:1:10 ratio (8). The individual VPs are expressed within the same open reading frame and share a C terminus that includes the entire VP3. VP1 and VP2 represent N-terminal extended forms of VP3. In addition, VP1 possesses ∼137-amino-acids (aa) N-terminal to VP2. This unique region of VP1 (VP1u) contains a phospholipase A2 (PLA2) domain, a calcium-binding domain, and a nuclear localization signal, all of which are required for AAV infectivity (9, 10).

The three-dimensional (3D) structures of numerous AAV capsids have been determined by either X-ray crystallography and/or cryo-electron microscopy and image reconstruction (cryo-EM) (11–24). The VP structures show ordering of only the common VP3 region, regardless of the method of structure determination. In these structures, the first ∼15 aa of VP3 are missing. The structure consists of a core eight-stranded (βB to βI) anti-parallel β-barrel motif, with a BIDG sheet forming the inner surface of the capsid. An additional strand, βA, runs antiparallel to the βB strand. Furthermore, all AAVs conserve an alpha helix (αA) located between βC and βD. Inserted between the β-strands are large loops of high sequence and structure variability that constitute AAV serotype-specific capsid surface features. These loops are named after their flanking β-strands (e.g., DE-/HI-loop). The sequence variability of different AAVs results in alternative conformations of the surface loops. Nine regions of significant diversity were defined as variable regions (VRs) by structural alignments (21).

Despite the differences on their capsid surfaces arising from various loop topologies, all AAVs conserve similar morphologies (reviewed in reference [4]). The icosahedral 5-fold symmetry axis is surrounded by DE-loops that form a cylindrical channel. This portal is believed to be the route of genomic DNA packaging and uncoating, and VP1u externalization during endo/lysosomal trafficking after cell entry (25, 26). At the 2-fold symmetry axis, depressions are flanked by protrusions surrounding the 3-fold symmetry axis, and the raised capsid regions between the 2- and 5-fold axes are termed 2/5-fold walls. The AAV capsids have multiple functions. They package and protect the viral genome and mediate the attachment to various host cell receptors, thereby determining the virus’ cell and tissue tropism. Many AAV serotypes utilize cell surface glycans as their first contact receptors. Among these are heparan sulfate proteoglycan binders (e.g., AAV2, AAV3, AAV6, and AAV13) (27–31), sialic acid binders (e.g., AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, and AAV6) (32–34), and terminal galactose binder (e.g., AAV9) (35, 36), and AAVrh.10 was shown to bind to a sulfated N-acetyl-lactosamine (LacNAc) on a glycan array (37). In addition, a series of protein receptors have been described, e.g., AAVR (38), laminin (39), αvβ1 integrin (40), αvβ5 integrin (41), the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (42), the fibroblast growth factor receptor (43), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (44). Following host cell entry, the AAV capsid is crucial for the delivery of the packaged genome through the endo/lysosomal pathway to the nucleus, where it is uncoated and replicated. In addition, the surface of the capsid displays antigenic sites for antibodies raised by the host immune response (45).

AAV variants isolated from rhesus macaque tissues are being developed for a variety of gene delivery applications. This is because of the lower percentage of preexisting neutralizing antibodies against their capsids in the human population (46) and their higher transgene expression in a variety of tissues in comparison to other AAV serotypes (47, 48). The primate AAVs are classified into six genetic groups (clades A to F) and two clonal isolates (5). AAV rhesus isolate 10 (AAVrh.10) and 39 (AAVrh.39) belong to clade E represented by AAV8 (5). The capsid amino acid sequence of AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 differ by ∼6.5% from AAV8 and exhibit different tissue tropisms compared to AAV8 (49, 50). They are reported to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and efficiently transduce neuronal cells (50–52) similar to AAV9 that belongs to clade F (53). This phenotype has resulted in the utilization of AAVrh.10 vectors in multiple clinical trials (54, 55) despite its basic biology being poorly understood. In this study, the structures of the AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 were determined by cryo-EM to 2.75- and 3.39-Å resolution, respectively. In addition, these structures were compared to the capsid structure of AAV8 determined to 3.08-Å resolution, also by cryo-EM. The only minor differences observed among the three viruses are at the previously described surface VR-IV. The absence of structural differences between the different AAVs at the proposed region responsible for BBB crossing in AAVrh.10 (52) points to specific amino acids that are similar to AAV9 for conferring this property. This suggests that S269 and N472, absent in AAV8, control this phenotype. A comparison of the empty (no DNA) and full (genome packaged) capsid structures for all three viruses showed that a previously described nucleotide binding pocket has extended DNA ordering in genome-containing particles. This observation confirms the assignment of this pocket as a conserved nucleotide interaction site and suggests that a role in genome packaging that is yet to be confirmed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cryo-EM reconstruction of empty and genome-containing particles.

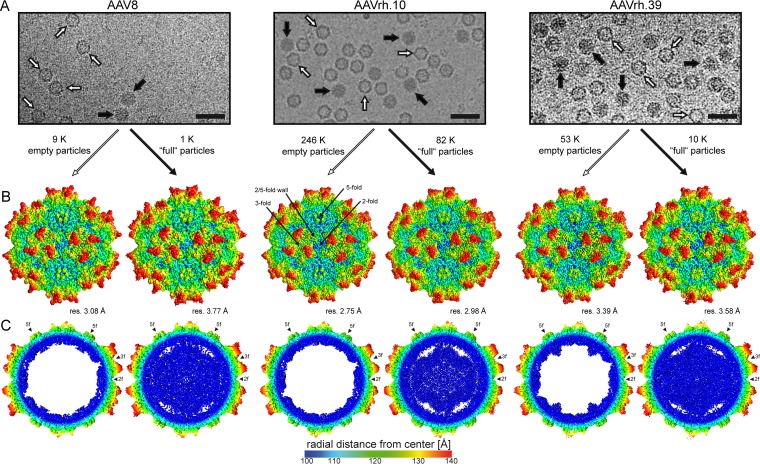

Recombinant rAAV8, rAAVrh.10, and rAAVrh.39 vectors produced by triple transfection in HEK293 cells were utilized for cryo-EM data collection. AVB affinity chromatography, used for sample purification, resulted in highly pure AAV vector preparations but did not separate empty (no genome) and genome-containing (full) particles as observed in cryo-EM micrographs (Fig. 1A). Further “purification” by separate particle picking, using their light (empty) and dark (full) appearances, enabled the independent structural determination of empty and full particles (Fig. 1B). For rAAV8, AAVrh.10, and rAAVrh.39, empty/full structures were determined from 8,574/1,072, 245,529/82,463, and 52,912/9,723 particles, respectively, to resolutions of 3.08/3.77, 2.75/2.98, and 3.39/3.58 Å (FSC 0.143), respectively (Fig. 1B, Table 1). The slightly lower resolution of the full structures compared to empty is likely due to the reduced number of particles used for the reconstructions. All three AAV structures, with up to 6.6% amino acid sequence variability, displayed the characteristic features common to AAV capsids: a channel at the 5-fold symmetry axis, protrusions surrounding the 3-fold symmetry axis, depressions at the 2-fold symmetry axis, and a 2/5-fold wall separating the depression surrounding the 5-fold axis and at the 2-fold axis (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Empty and genome-containing AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 capsid structures. (A) Electron micrographs show the presence of empty (white arrow) and genome-containing particles (black arrow). Scale bar, 50 nm. (B) Capsid surface density maps determined by cryo-EM reconstruction contoured at a sigma (σ) threshold level of 1. The resolutions of the structures are calculated based on an FSC threshold of 0.143. The reconstructed maps are radially colored (blue to red) according to distance to the particle center, as indicated by the scale bar below. The icosahedral 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes and the 2/5-fold wall are indicated on the empty AAVrh.10 map. (C) Cross-sectional views of the reconstructed maps from genome-containing and empty particles contoured at a threshold level of 0.9. The positions of some icosahedral 2-, 3-, and 5-fold symmetry axes are indicated by arrowheads. This figure was generated using UCSF-Chimera (78).

TABLE 1.

Summary of data collection and image-processing parameters

| Processing or refinement parameter | AAV8 |

AAVrh.10 |

AAVrh.39 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full | Empty | Full | Empty | Full | Empty | |

| Processing parameters | ||||||

| Total no. of micrographs | 782 | 2,146 | 2,413 | 2,415 | 1,326 | 1,684 |

| Defocus range (μm) | 0.84–3.37 | 0.79–3.91 | 0.85–4.05 | 0.85–4.05 | 0.84–4.11 | 0.84–4.11 |

| Total electron dose (e–/Å2) | 67 | 67 | 60 | 60 | 64 | 64 |

| No. of frames/micrograph | 39 | 39 | 45 | 45 | 37 | 37 |

| Pixel size (Å/pixel) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Starting no. of particles | 1,072 | 8,574 | 82,463 | 245,529 | 9,723 | 52,912 |

| No. of particles used for final map | 974 | 6,878 | 46,558 | 84,375 | 5,997 | 30,949 |

| Inverse B factor used for final map (Å2) | −1/25 | −1/50 | −1/100 | −1/100 | −1/75 | −1/100 |

| Resolution of final map (Å) | 3.77 | 3.08 | 2.98 | 2.75 | 3.58 | 3.39 |

| Refinement statistics | ||||||

| Map CC | 0.849 | 0.877 | 0.793 | 0.871 | 0.812 | 0.787 |

| RMSD (bonds) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| RMSD (angles) | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.84 |

| All-atom clashscore | 9.44 | 6.27 | 9.22 | 7.40 | 10.26 | 8.81 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||||||

| Outliers | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Allowed | 2.7 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 3.7 |

| Favored | 97.1 | 98.1 | 97.9 | 98.5 | 97.4 | 96.3 |

| Rotamer outliers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cβ deviations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

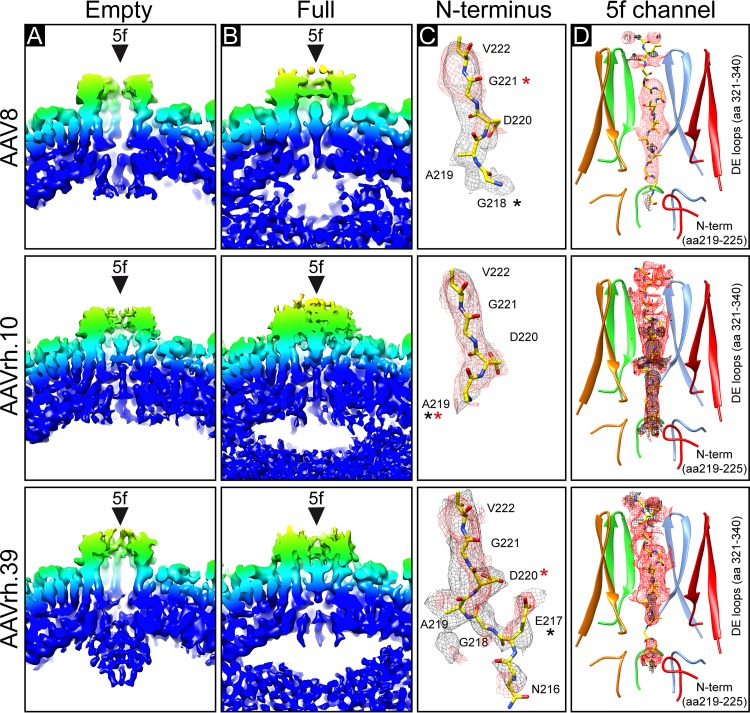

While the reconstructed density maps looked very similar on the outer capsid surface for the empty/full structures (Fig. 1B), cross sections showed a significant amount of density in the interior of the full particles that are absent from the corresponding empty maps (Fig. 1C). Another distinguishing feature of the empty and full maps was density (observed at a sigma [σ] threshold of 0.9) extending beneath the 5-fold channel for the empty AAV8 and AAVrh.39 capsid structures, but not in the AAVrh.10 empty structure (Fig. 1C and 2A to C). Interestingly, this basket-like density in the empty structures occupies the equivalence of a “gap” in full structures (Fig. 1C and Fig. 2A and B). The third difference between the empty and full structures is the presence of density within the 5-fold channel in the full maps for AAV8 and AAVrh.39 but not in the empty maps. In contrast, the AAVrh.10, for which the empty structure does not have an interior basket at this symmetry axis, there is density within the channel of both the empty and full structures (Fig. 2A and D).

FIG 2.

Fivefold region of empty and full AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 capsids. (A and B) Close-up cross-sectional views at the 5-fold symmetry axis in empty (A) and genome-containing (B) maps for AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39. The maps are colored as for Fig. 1. (C) Modeled N termini of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 residues are shown inside their mesh density maps (black, empty; red, full). The amino acids are shown as stick representation. Atom colors: C, yellow; O, red; N, blue. The first ordered residue in each map is indicated by an asterisk (black, empty; red, full). (D) The density in the channel at the 5-fold axis for the empty and full AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 maps is contoured at a σ threshold level of 0.9. Residues 198 to 209 are modeled inside the channel. This figure was generated using UCSF-Chimera (78).

The capsid structures of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 are conserved.

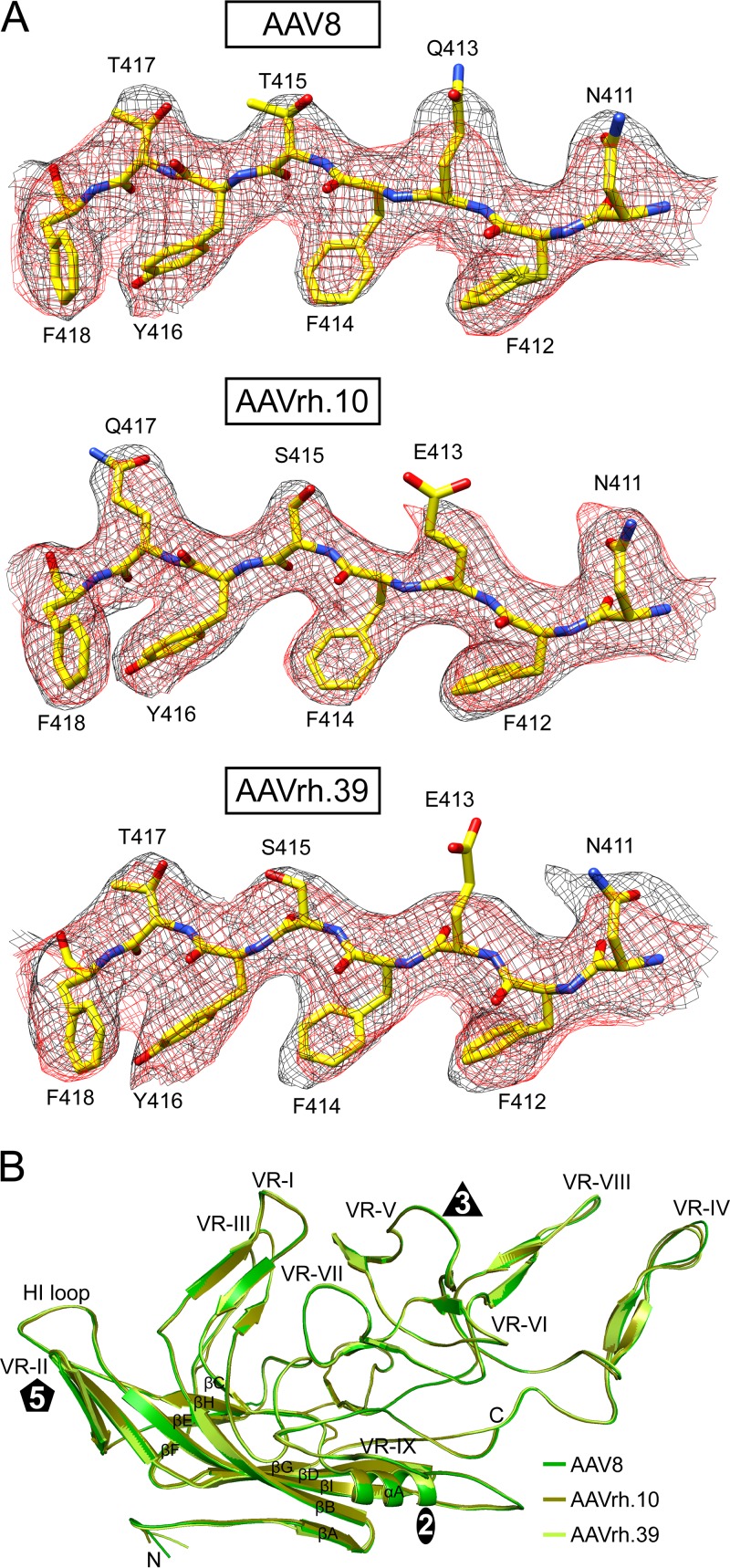

The resolution of the maps enabled the unbiased building of atomic models for AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39, based on their respective VP3 sequences. Different amino acid side chain densities in the equivalent positions of the VP, such as T417 or Q417 were readily identifiable (Fig. 3A). The first observed ordered amino acids at the N termini within the VP3 common region for the three maps was glutamic acid 217 (in AAVrh.39), glycine 218 (in AAV8), and alanine 219 (in AAVrh.10) (Fig. 2C). This is comparable to most other previously described AAV capsid structures (11–13, 15–18, 20–24). Amino acid side chain densities were interpretable to the last C-terminal residue, 738, in all three maps at ∼2σ. An exception is the apex of VR-IV showing disorder in all three viruses. Residues aa 455 to 457 in AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 showed high level of disorder preventing reliable building of the main and side chains. For the corresponding amino acids in AAV8 the main chain could be built at 1.5σ suggesting better ordering. The structural disorder within VR-IV is likely due to flexibility caused by the presence of glycine residues in this short stretch of amino acids: GGTAN, GGTAG, and GGTQG for AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39, respectively. It is possible that having two instead of three glycines reduced flexibility and thus disorder in AAV8.

FIG 3.

Structural comparison of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39. (A) The modeled AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 residues are shown inside their mesh density maps (black, empty; red, full). The high resolution enables the clear assignment of the map to the different AAV variants at positions with alternative amino acids. The larger side chain density at position 417 identifies AAVrh.10 that possesses a glutamine residue compared to AAV8’s and AAVrh.39’s threonine. The truncated density for the glutamic acid side chain (E413) is due to high sensitivity of acidic residues to radiation damage caused by cryo-electron microscopes (84). The amino acids are shown as stick representation. Atom colors: C, yellow; O, red; N, blue. This figure was generated using UCSF-Chimera (78). (B) Structural superposition of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 VP shown as ribbon diagrams. The conserved β-barrel core motif (βB to βI), βA, and the αA helix are indicated, the positions of VR-I to VR-IX are labeled, and the approximate icosahedral 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes are represented by an oval, triangle, and pentagon, respectively. This image was generated using PyMOL (85).

Similar to all other AAV structures, the VP monomers of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 consist of the core eight-stranded (βB to βI) anti-parallel β-barrel motif with the additional βA strand and the alpha helix (αA) located between βC and βD (Fig. 3B). The surface loops containing the VRs (VR-I to VR-IX) are similar among AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39. Structural superposition of the Cα coordinates for the three AAVs (Fig. 3B) resulted in root mean square deviations (RMSDs) of 0.5 Å for AAV8 versus AAVrh.10, 0.6 Å for AAV8 versus AAVrh.39, and 0.5 Å for AAVrh.10 versus AAVrh.39. The minor difference in topology indicated at the apex of VR-IV for AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 may not be accurate due to the flexibility of this VP region described above (Fig. 3B). Notably, while this is the first report of the capsid structures of AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39, the capsid structure of AAV8 has been previously determined by X-ray crystallography (11, 56). The superposition of the atomic model coordinates of the AAV8 crystal and cryo-EM structures resulted in an RMSD of 0.5 Å with no significant deviations of the VP main chain or side chains.

Structural comparison of empty and full capsids of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39.

Direct comparison of the empty and full structures for each virus showed no significant differences in the ordered VP3 region, with RMSDs of 0.2 Å for the AAVrh.10 structures and 0.3 Å for the AAV8 and AAVrh.39 structures. These values are similar for pairwise structural alignments of previously reported crystal structures of virus-like particles (VLPs) and full particles of AAV6 [PDB 3OAH versus PDB 4V86] (18, 57) and AAV8 [PDB 2QA0 versus PDB 3RA4] (11, 56) resulting in RMSDs of 0.4 and 0.2 Å, respectively. In contrast to these high-resolution structures, a direct comparison of empty and full AAV1 particles at ∼10-Å resolution, determined by cryo-EM, reported conformational rearrangements of the β-barrel (58). Rearrangements of this magnitude have not been reported for any other parvovirus empty/full structure comparison and were not observed for the current AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 structures.

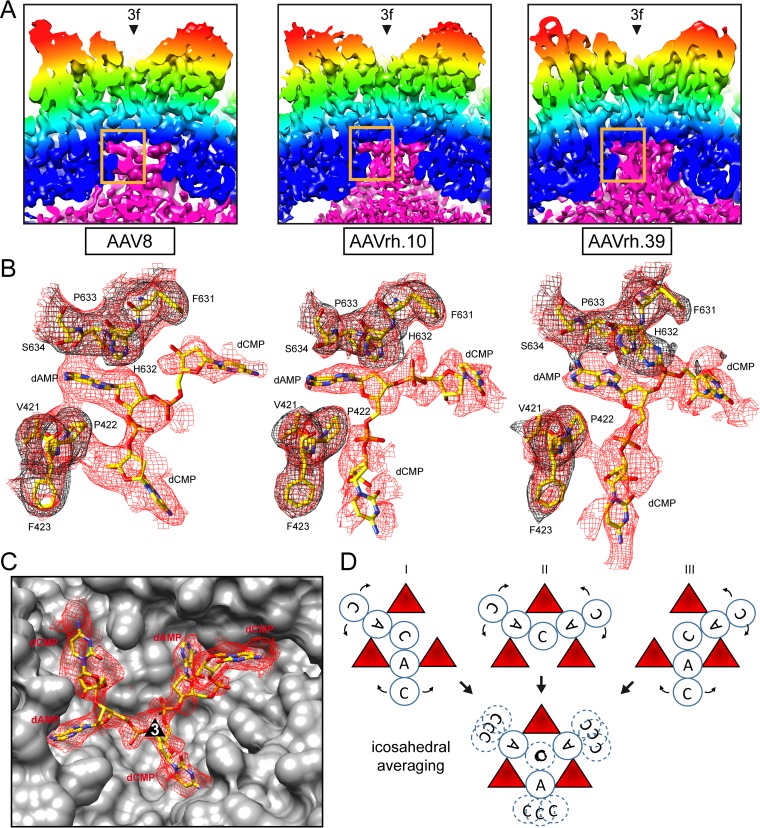

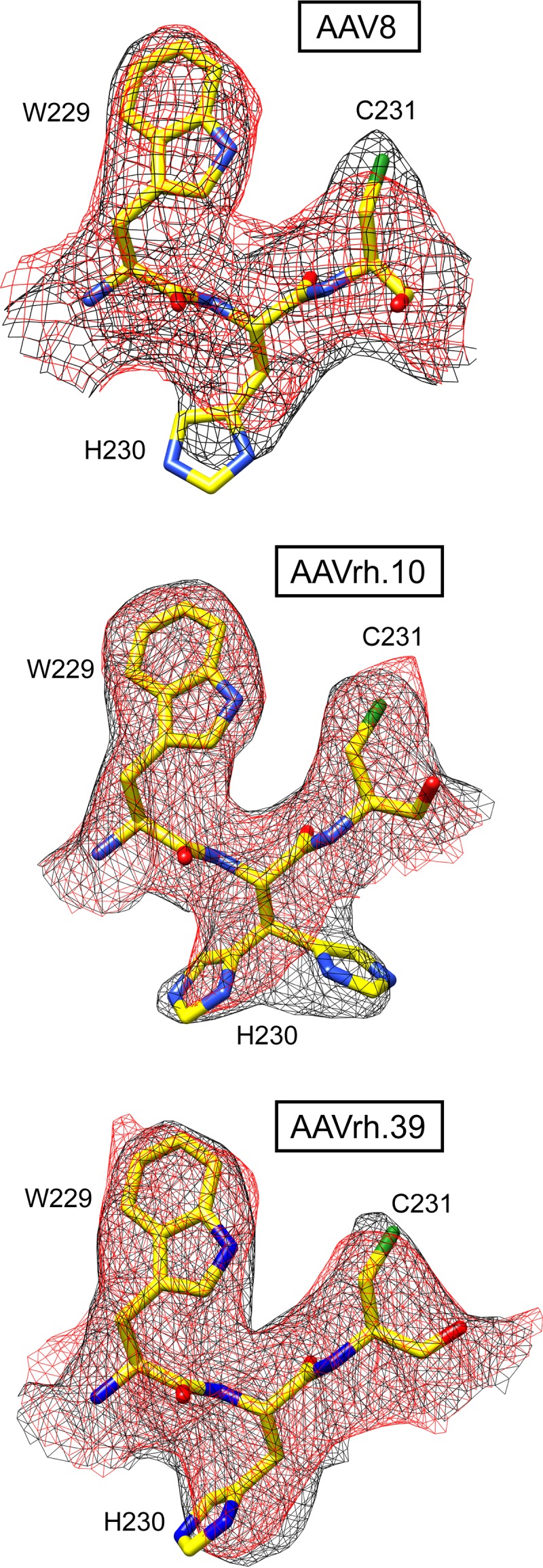

As previously stated, three main differences exist between the empty and full density maps: (i) electron density fills the interior of the full structures, (ii) the basket-like density in the empty AAV8 and AAVrh.39 particles extend the channel at the 5-fold axis, and (iii) the full structures for all three viruses, as well as the empty AAVrh.10 structure, have density within the 5-fold channel (Fig. 1C, 2, and 4A). The additional density in full capsids extend into a pocket underneath the 3-fold-symmetry axis while leaving a gap at the 5-fold axis (Fig. 2B and 4A). An adenine nucleotide could be built into the portion of this density (at 1.5σ) inserted between VP3 amino acids P422 and H632/P633 offset from the 3-fold axis (Fig. 4B). This assigned nucleotide density is contiguous with additional low sigma density (at 0.8 σ) flanking either side of the adenosine nucleotide, exiting the 3-fold pocket and filling the remaining void in the pocket, leading toward the 3-fold symmetry axis. These nucleotides, not as well ordered compared to the adenine nucleotide, were interpreted as cytosines; thus, a dCAC trinucleotide was built (Fig. 4B). Two of these nucleotides, the 5′ dCMP and dAMP, are structurally equivalent to those previously reported in the crystal structure of AAV8 full particles (56). The application of icosahedral symmetry to the VP model, including the dCAC, to generate a capsid, likely results in steric clashes of the dC nucleotides positioned at the 3-fold axes. This suggests that only one ssDNA strand can lead into the 3-fold pockets and interacting with two symmetry-related VP P422 and H632/P633 pockets before exiting the 3-fold pocket. Thus, three possible “pathways” for the ssDNA ordering could be interpreted to generate a pentanucleotide chain at the 3-fold region (Fig. 4C and D). The less ordered state of the DNA density in all three maps compared to the surrounding VP density is likely due to the fact that the ssDNA does not follow icosahedral symmetry (unlike VP3), which was imposed during the 3D image reconstruction (Fig. 4B and C). While the positioning of the DNA density was similar in all three viruses, H632 adopts a dual conformation in AAVrh.39 that introduces minor differences in interaction and juxtaposition between the ordered nucleotides and VP atoms among the three viruses (Fig. 4B). Significantly, side chain movement of residues F631 and H632, “the HIS-PHE switch,” was proposed as a mechanism for the loss of VP-DNA interaction as the pH decreases in full AAV8 particles, resulting in the loss of DNA density (56). The orientation of H632 in all three viruses is consistent with the DNA binding position observed in other AAVs (17, 18, 20, 21, 24, 56) and the dual orientation in AAVrh.39 appears to stabilize the phosphodiester bond between the dAMP and the 3′ dCMP (Fig. 4B). Histidine 632 is not the only residue displaying dual conformation in these structures. Notably, histidine 230 also adopts a dual conformation in the empty AAVrh.10 structure (Fig. 5) but not in the full particles or in the AAV8 and AAVrh.39 structures. This residue is located near the 5-fold symmetry axis and the dual conformation may be related to the observed differences of the 5-fold region in empty AAVrh.10 particles versus the AAV8 and AAVrh.39 particles.

FIG 4.

Comparison of nucleotide binding pocket in empty and full particles. (A) Close-ups of cross-sectional views underneath the 3-fold symmetry axis based on the empty maps, colored as for Fig. 1. The additional density of the full maps is colored in pink showing the position of the nucleotide binding pocket (rectangle). (B) The modeled AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 residues at the nucleotide binding pocket are shown inside their mesh density maps (black, empty; red, full). The presence of extra density including an ordered nucleotide (dAMP) exclusively in the full maps of AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 can be observed. The more disordered density on either side of the dAMP was interpreted as cytosine nucleotides (dCMP). (C) A pentanucleotide built based on density at the 3-fold symmetry axis is shown for the full AAVrh.39 structure (as an example) inside a red mesh density map. The location of the 3-fold symmetry axis is indicated. Panels A to C were generated using UCSF-Chimera (78). (D) Three models of a pentanucleotide (CACAC) DNA strand shown at the 3-fold DNA binding pocket. Since the DNA does not follow icosahedral symmetry, icosahedral averaging results in the disorder of nucleotides (circles with broken lines). Atom colors: C, yellow; O, red; N, blue.

FIG 5.

Dual conformation of histidine 230. The modeled AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 residues are shown inside their mesh density maps (black, empty; red, full). Atom colors: C, yellow; O, red; N, blue; S, green. Histidine 230 adopts alternative side chain conformations in the absence of packaged DNA exclusively in AAVrh.10. This figure was generated using UCSF-Chimera (78).

The 3-fold pocket is the previously described AAV nucleotide-binding site conserved among AAV serotypes (11, 17, 18, 20, 21, 24). However, these previous reports include an ordered nucleotide in “empty” AAV6 and AAV8 VLPs (11, 18). The presence of an ordered nucleotide in an otherwise empty capsid led to the hypothesis that the AAV capsids might require a nucleotide to initiate capsid assembly (11). The present study suggests that previous observations were due to both empty and DNA-packaged particles in samples crystallized rather than an assembly requirement because of the lack of nucleotide density in the empty structures. The previous reports thus support reports of AAV packaging cellular pieces of DNA in the absence of Rep proteins (59). A prior study of AAV8 showed that while exposure to low-pH conditions reduces nucleotide ordering in full particles, this is reversible when conditions are restored to pH 7.5 (56). Thus, the low pH used for elution during AVB purification is not responsible for the lack of interior density in the empty particles.

A similar density to that extending the channel at the 5-fold axis in the empty AAV8 and AAVrh.39 structures has been previously reported for bocaparvoviruses (BoVs) VLPs and AAV5 VLPs complexed an FAb (60–62). The first N-terminal residue in the ordered VP region for all currently known parvovirus VP structures is located at the base of the 5-fold channel (63). In the BoV and AAV5 complex structures, the main chain of additional N-terminal amino acids, compared to other parvovirus VPs and wild-type AAV5 were built into the basket density (60, 61). Empty AAVrh.10 particles did not show any extended density below the 5-fold channel and the first ordered N-terminal residue is alanine 219 (Fig. 2C). In empty AAV8 particles the N-terminal density is slightly extended which allowed the building of an additional residue, glycine 218 (Fig. 2C). However, in full AAV8 particles the ordered density is truncated to glycine 221. The basket-like structure in empty AAVrh.39 particles allowed the building of additional amino acids up to asparagine 216 (Fig. 2C), which suggests that the N terminus is projected into the interior in empty but not in full capsids. AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 have no amino acid differences at their VP N termini, and the same genome was packaged into all three viruses; thus, the reason for the difference in the 5-fold basket ordering among them remains to be determined.

Notably, the gap observed in the additional density in the full capsids underneath the 5-fold channel coincides with density inside the channel of the full structures for all three viruses (Fig. 1C, 2B, and D). In addition, the AAVrh.10 empty map, with no basket, has density within the 5-fold channel (Fig. 2A). Previous studies suggest that the VP1u of parvoviruses is externalized via the 5-fold channel for its PLA2 enzyme function (25). The VP1/2 common region also requires externalization for its nuclear localization functions, which is also proposed to occur via the 5-fold channel. Thus, it is possible that the flexible VP1/VP2 common region and VP1u normally occupy the space under the 5-fold channel and that the gap observed is because these VP regions are externalized in the three full structures and AAVrh.10 empty structure. Density in the 5-fold channel has been reported for crystal structures of AAV8 VLPs and full AAVrh.8 capsids (11, 17). As discussed above, the AAV8 VLP structures previously reported were likely a mixture of empty capsids and those containing fragments of DNA. Significantly, the rod-shaped densities in the 5-fold channels observed here are reminiscent of the channel density reported for AAVrh.8 (Fig. 2D) (17). Interpretation of the exact amino acids in the channel density is difficult because this stretch at the 5-fold symmetry axis is icosahedrally averaged, and it did not connect to the first ordered residues, nor did it extend further inside the capsid to the basket residue. However, due to the narrow diameter of the channel, a stretch of amino acids with small side chains such as, for example aa 198 to 209 (GLGSGTMAAGGG) is suggested. The presence of several glycines to confer flexibility to the VP N termini would facilitate externalization of the enzymatic VP1u region. The absence of the channel density in the AAV8 and AAVrh.39 empty capsid structures and presence of the basket underneath the 5-fold channel is consistent with the lack of externalized N-terminal VP regions and indicates their positioning within the capsid interior.

Specific residues determine the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier.

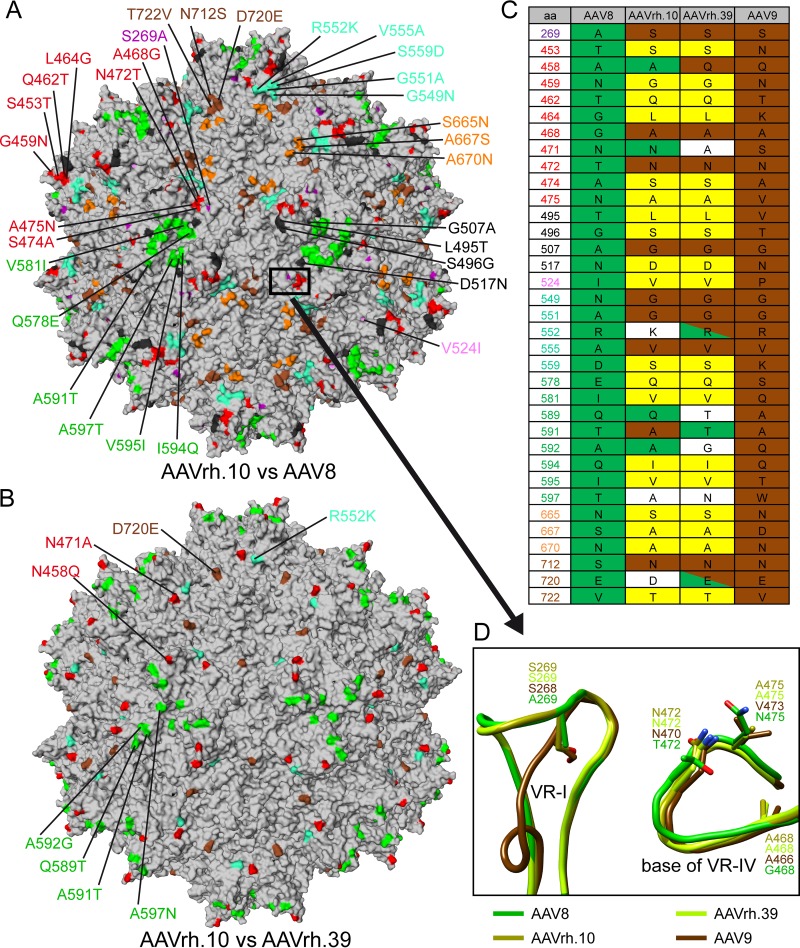

One of the advantages of AAVrh.10 is its natural ability to cross the BBB and transduce neuronal cells similar to AAV9 (50, 52, 53). Unlike AAV8, AAVrh.39 is also capable of crossing the BBB and efficiently transduces neuronal cells and keratinocytes but possesses an alternative tissue tropism to different neuronal cell types compared to AAVrh.10 (50). Due to the high structural similarity of these viruses, the difference in the ability to cross the BBB is thus likely based on amino acid differences within the VRs. The majority of the 48 amino acid differences between AAV8 and AAVrh.10 are located within or near the VRs on the capsid surface (Fig. 6A). Similarly, most amino acid differences between AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 are also located on the capsid surface (Fig. 6B). In the case of AAVrh.10, BBB crossing was previously mapped to VR-I (52). In this regard, it makes sense that AAVrh.39 shares the same ability since there is no structural or sequence difference in both AAVs in this region. AAV8 is also structurally similar in VR-I compared to AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 but displays a single amino acid difference (S269A) (Fig. 6D). This points to the importance of serine 269 in the BBB crossing ability. Interestingly, AAV9, which is also able to cross the BBB, conserves the serine (S268) in VR-I (Fig. 6C and D). Despite the fact that the AAV9 VR-I adopts a different loop configuration compared to AAV8, AAVrh.10, or AAVrh.39, the serine side chain is located approximately in the same position in all three structures where it is conserved (Fig. 6D). In a recent study, the amino acids of AAVrh.10 VR-I were substituted to the corresponding sequences of AAV1 (AAVRX1) and the BBB-crossing efficiency was reduced in this variant but not completely lost (64). This indicates that additional amino acids of the AAVrh.10 capsid act together with serine 269 to achieve the BBB crossing phenotype. In order to identify these residues, differences on the capsid surfaces of AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 compared to AAV8 were analyzed and subsequently cross-checked with AAV9 (Fig. 6C and D). Among the shared differences for AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 to AAV8, eight amino acids are identical to AAV9, including serine 269 (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, two additional shared amino acids are in close proximity to serine 269 and are located at the base of VR-IV. Asparagine 472 (N470 in AAV9) is located ∼7.5 Å away with identical side chain orientations (Fig. 6D). This amino acid is reported to be important for galactose binding in AAV9 (65). Among numerous AAVs compared, no other serotype contains this asparagine in this position, including AAV8 that has a threonine (Fig. 6D). The second residue is alanine 468 (A466) with a distance of ∼6 Å to asparagine 472, which is a glycine in AAV8. In addition, alanine 475 of AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 might preserve a more hydrophobic environment similar to AAV9 with a valine (V473) unlike AAV8 with an asparagine (N465) (Fig. 6D). It would be interesting to see whether the mutation of asparagine 472 in AAVRX1 (64) completely knocks out the capability to cross the BBB.

FIG 6.

Comparison of the capsid surfaces of AAV8, AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39. (A) Gray surface representation of the AAVrh.10 capsid generated from 60 VP monomers. The amino acid differences to AAV8 on the capsid surface are colored and an example of each is labeled. (B) Surface representation of the AAVrh.10 capsid showing the locations of amino acid differences to AAVrh.39. Example residues are labeled. (C) Tabular overview of all capsid surface amino acid differences between AAV8, AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39. In addition, the corresponding amino acid in AAV9 is shown. Residues highlighted in green are present in AAV8 or identical to AAV8. Similarly, residues in brown are present in AAV9 or are shared with AAV9. Amino acids highlighted in yellow are found exclusively in AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39. (D) Structural comparison of the region proposed to confer ability to cross the BBB. Its approximate location on the full capsid is shown by the rectangle in panel A. This image was generated using PyMOL (85).

Conclusions.

Following its identification in 2003, from rhesus macaque tissues (66), vectors based on AAVrh.10 have been utilized in multiple clinical trials to treat monogenetic diseases, including Sanfilippo syndrome type A (55), metachromatic leukodystrophy (54), Batten Disease, or hemophilia B (https://clinicaltrials.gov). In contrast to AAV8 and AAVrh.10, AAVrh.39 is yet to be used in a clinical trial, but studies show promise in certain neuronal cells and in keratinocytes (49, 50). The capsid structures of clinical vectors at atomic resolution provides an additional feature for product identification and approval if needed by the FDA or the EMA since they require sufficient knowledge of the vector background for evaluation (67). In addition, by providing atomic detailed information, the available structures can serve as a platform for further engineering toward improved characteristics. Potential capsid engineering targets include surface-exposed tyrosine, serine, threonine, and lysine amino acids to prevent phosphorylation or ubiquitination of the capsid that leads to their degradation following cellular entry to improve gene therapy success related to transduction efficiency (68, 69). Furthermore, the capsid surface information will aid future engineering attempts to generate AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 variants with the ability to (i) escape preexisting neutralizing antibodies based on information on known epitopes for other AAVs (70) or (ii) target different cell types based on tissue tropism information (50).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant AAV production and purification.

Recombinant AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 vectors, with a packaged luciferase gene, were produced by triple transfection of HEK293 cells, utilizing pTR-UF3-Luciferase, pHelper (Stratagene), and either pXR8, pAAV2/rh.10, or pAAV2/rh.39; purified by AVB Sepharose affinity chromatography; and concentrated as previously described (60).

Cryo-EM data collection.

Small aliquots (3.5 μl) of purified rAAV vectors were applied to glow-discharged Quantifoil copper grids with 2-nm continuous carbon support over holes (Quantifoil R 2/4 400 mesh), blotted, and vitrified using a Vitrobot Mark 4 (FEI) at 95% humidity and 4°C. The particle distribution and ice quality of the grids were screened in-house using an FEI Tecnai G2 F20-TWIN microscope (FEI Co.) operated under low-dose conditions (200 kV, ∼20 e−/Å2). Images were collected on a GatanUltraScan 4000 charge-coupled device camera (Gatan). Grids deemed suitable for high-resolution data collection were used for collecting micrograph movie frames using the Leginon application (71) on a Titan Krios electron microscope. The microscope was operated at 300 kV, and data were collected on a DE20 (for AAV8 and AAVrh.39) or DE64 (for AAVrh.10) direct electron detector (Direct Electron). During data collection, a total dose of 60 to 67 e−/Å2 was utilized for 37 to 40 movie frames per micrograph. The movie frames collected on the DE20 detector were aligned using the DE_process_frames software package (Direct Electron) without dose weighting as previously described (61, 72). MotionCor2 was used for aligning the movie frames collected on the DE64 detector with dose weighting (73). The data sets were collected as part of the NIH Southeastern Center for Microscopy of MacroMolecular Machines (SECM4) project.

Icosahedral 3D image reconstruction.

Individual particle images were selected from the aligned micrographs using the semiautomated and automated boxing application e2boxer subroutine in the EMAN2 program (74) and coordinated files converted to the bcrd format using the auto3dem subroutine box2bcrd. The AUTOPP subroutine (options F and O) of AUTO3DEM was used for preprocessing (normalization and apodization) of the extracted particle images (75). The defocus values for each micrograph were estimated using CTFFIND4, embedded in AUTOPP (option 3X), to correct the microscope-related contrast transfer functions (CTFs) (76). Initial models at low resolution (i.e., ∼30-Å resolution) were generated from 100 particle images using the ab initio model generating subroutine within AUTO3DEM while applying icosahedral symmetry (75). For each reconstruction, the entire data set was used to search the particles’ origins and orientations, followed by cycles of origin and orientation refinement, solvent flattening, and CTF refinement. In the case of the AAV8 and AAVrh.39 data sets, which utilized the non-dose-weighted images, the movie frames were realigned by truncating the number of frames to 3 to 20. This step aimed to minimize the effects of drift in early movie frames and potential radiation damage in latter movie frames. The new images were used for further rounds of refinement, followed by removal of outlier particles with the “score fraction” option within AUTO3DEM (75). For all data sets, different B-factor (temperature factor) values—1/50, 1/100, 1/150, and 1/175 Å2—were applied to sharpen the high-resolution features of the resulting final maps, followed by visual inspection in the Coot and Chimera applications (77, 78). The resolution of each cryo-reconstructed map was calculated based on a Fourier shell correlation (FSC) of 0.143 (Table 1).

Model building and structure refinement.

3D homology models of AAVrh.10 and AAVrh.39 VP3 were generated using their amino acid sequences (NCBI accession numbers AAO88201.1 and ACB55313.1, respectively) in the protein structure homology-modeling server Swiss-Model (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) with the crystal structure of AAV8 (RCSB PDB 2QA0) supplied as a template (11, 79). A 60-mer coordinate model was generated from the VP3 with the VIPERdb2 oligomer generator subroutine by icosahedral matrix multiplication (80). The 60-mer capsid models of each AAV were docked into the cryo-reconstructed density maps of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 by rigid body rotations and translations using the “fit in map” subroutine within UCSF-Chimera (78) that uses a correlation coefficient (CC) calculation to assess the quality of the fit between the map generated from the model and the reconstructed map. During the model fitting, the voxel (pixel) size of each reconstructed map was adjusted to optimize the CC between the models and maps. The fitted models were exported relative to the respective map for further use. Each map was resized to the voxel size determined in Chimera using the “e2proc3D.py” subroutine in EMAN2 (74) and then converted to the CCP4 format using the program MAPMAN (81). A VP monomer was extracted from each 60-mer, and the side and main chains were adjusted into the maps by manual building and use of the real-space-refinement subroutine in Coot (77). The adjusted capsid model was refined against the map utilizing the rigid-body, real-space, and B-factor refinement subroutines in Phenix (82). Model refinement was alternated with visualization and adjustment using Coot to maintain model geometry, as well as rotamer and Ramachandran constraints (77). The CC and refinement statistics, including the RMSD from ideal bond lengths and angles (Table 1), were analyzed using Phenix (82).

AAV capsid structure comparison.

The Cα positions of all ordered residues within the VP3 atomic coordinates of AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.8 were superposed using secondary structure matching (SSM) in Coot (83). The SSM subroutine generated RMSD values between the structures and calculated distances between the aligned Cα positions.

Data availability.

The full and empty AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 cryo-EM reconstructed density maps and models built for their capsids were deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) with accession numbers EMD-21004/PDB ID 6V10 (AAV8 full), EMD-21010/PDB ID 6V12 (AAV8 empty), EMD-21011/PDB ID 6V1G (AAVrh.10 full), EMD-0663/PDB ID 6O9R (AAVrh.10 empty), EMD-21020/PDB ID 6V1Z (AAVrh.39 full), and EMD-21017/PDB ID 6V1T (AAVrh.39 empty), respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the UF-ICBR Electron Microscopy Core for access to electron microscopes utilized for negative-stain electron microscopy and cryo-EM screening. The Spirit and TF20 cryo-electron microscopes were provided by the UF College of Medicine (COM) and Division of Sponsored Programs. Data collection at Florida State University was made possible by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant S10 OD018142-01 purchase of a direct electron camera for the Titan-Krios at FSU (PI Taylor), S10 RR025080-01 purchase of a FEI Titan Krios for 3D EM (PI Taylor), and U24 GM116788 The Southeastern Consortium for Microscopy of MacroMolecular Machines (PI Taylor). The University of Florida COM and NIH GM082946 (to M.A.-M. and R.M.) provided funds for the research efforts at the University of Florida.

We acknowledge Mandy E. Janssen and Timothy Baker (both University of California—San Diego), who previously collected cryo-EM data on AAVrh.10 particles resulting in lower-resolution maps that were not included in the present study. We thank Kim Van Vliet, who previously attempted to crystallize a different batch of AAVrh.10 not included here. We also thank Phillip Tai for critical readings of the manuscript.

M.A.-M. is an SAB member for Voyager Therapeutics, Inc., and AGTC, has a sponsored research agreement with Voyager Therapeutics and Intima Biosciences, Inc., and is a consultant for Intima Biosciences, Inc. M.A.-M. is a cofounder of StrideBio, Inc. This is a biopharmaceutical company with interest in developing AAV vectors for gene delivery application.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott LJ. 2015. Alipogene tiparvovec: a review of its use in adults with familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Drugs 75:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd A, Piglowska N, Ciulla T, Pitluck S, Johnson S, Buessing M, O’Connell T. 2019. Estimation of impact of RPE65-mediated inherited retinal disease on quality of life and the potential benefits of gene therapy. Br J Ophthalmol 103:1610. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldrop MA, Kolb SJ. 2019. Current treatment options in neurology-SMA therapeutics. Curr Treat Options Neurol 21:25. doi: 10.1007/s11940-019-0568-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt J. 2011. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol 807:47–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, Wilson JM. 2004. Clades of Adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol 78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt M, Katano H, Bossis I, Chiorini JA. 2004. Cloning and characterization of a bovine adeno-associated virus. J Virol 78:6509–6516. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6509-6516.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bossis I, Chiorini JA. 2003. Cloning of an avian adeno-associated virus (AAAV) and generation of recombinant AAAV particles. J Virol 77:6799–6810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.12.6799-6810.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snijder J, van de Waterbeemd M, Damoc E, Denisov E, Grinfeld D, Bennett A, Agbandje-McKenna M, Makarov A, Heck AJ. 2014. Defining the stoichiometry and cargo load of viral and bacterial nanoparticles by Orbitrap mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc 136:7295–7299. doi: 10.1021/ja502616y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girod A, Wobus CE, Zadori Z, Ried M, Leike K, Tijssen P, Kleinschmidt JA, Hallek M. 2002. The VP1 capsid protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 is carrying a phospholipase A2 domain required for virus infectivity. J Gen Virol 83:973–978. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-5-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popa-Wagner R, Porwal M, Kann M, Reuss M, Weimer M, Florin L, Kleinschmidt JA. 2012. Impact of VP1-specific protein sequence motifs on adeno-associated virus type 2 intracellular trafficking and nuclear entry. J Virol 86:9163–9174. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00282-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nam HJ, Lane MD, Padron E, Gurda B, McKenna R, Kohlbrenner E, Aslanidi G, Byrne B, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2007. Structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 8, a gene therapy vector. J Virol 81:12260–12271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01304-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govindasamy L, Dimattia MA, Gurda BL, Halder S, McKenna R, Chiorini JA, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2013. Structural insights into adeno-associated virus serotype 5. J Virol 87:11187–11199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00867-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burg M, Rosebrough C, Drouin LM, Bennett A, Mietzsch M, Chipman P, McKenna R, Sousa D, Potter M, Byrne B, Jude Samulski R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2018. Atomic structure of a rationally engineered gene delivery vector, AAV2.5. J Struct Biol 203:236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan YZ, Aiyer S, Mietzsch M, Hull JA, McKenna R, Grieger J, Samulski RJ, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M, Lyumkis D. 2018. Sub-2 A Ewald curvature corrected structure of an AAV2 capsid variant. Nat Commun 9:3628. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie Q, Bu W, Bhatia S, Hare J, Somasundaram T, Azzi A, Chapman MS. 2002. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:10405–10410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162250899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiMattia MA, Nam HJ, Van Vliet K, Mitchell M, Bennett A, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Olson NH, Sinkovits RS, Potter M, Byrne BJ, Aslanidi G, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2012. Structural insight into the unique properties of adeno-associated virus serotype 9. J Virol 86:6947–6958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07232-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halder S, Van Vliet K, Smith JK, Duong TT, McKenna R, Wilson JM, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2015. Structure of neurotropic adeno-associated virus AAVrh.8. J Struct Biol 192:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng R, Govindasamy L, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Parent KN, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2010. Structural characterization of the dual glycan binding adeno-associated virus serotype 6. J Virol 84:12945–12957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01235-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drouin LM, Lins B, Janssen M, Bennett A, Chipman P, McKenna R, Chen W, Muzyczka N, Cardone G, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2016. Cryo-electron microscopy reconstruction and stability studies of the wild type and the R432A variant of adeno-associated virus type 2 reveal that capsid structural stability is a major factor in genome packaging. J Virol 90:8542–8551. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00575-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerch TF, Xie Q, Chapman MS. 2010. The structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 3B (AAV-3B): insights into receptor binding and immune evasion. Virology 403:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Kaludov N, Chiorini JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2006. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J Virol 80:11556–11570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01536-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guenther CM, Brun MJ, Bennett AD, Ho ML, Chen W, Zhu B, Lam M, Yamagami M, Kwon S, Bhattacharya N, Sousa D, Evans AC, Voss J, Sevick-Muraca EM, Agbandje-McKenna M, Suh J. 2019. Protease-activatable adeno-associated virus vector for gene delivery to damaged heart tissue. Mol Ther 27:611. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerch TF, O’Donnell JK, Meyer NL, Xie Q, Taylor KA, Stagg SM, Chapman MS. 2012. Structure of AAV-DJ, a retargeted gene therapy vector: cryo-electron microscopy at 4.5 Å resolution. Structure 20:1310–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikals K, Nam HJ, Van Vliet K, Vandenberghe LH, Mays LE, McKenna R, Wilson JM, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2014. The structure of AAVrh32.33, a novel gene delivery vector. J Struct Biol 186:308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venkatakrishnan B, Yarbrough J, Domsic J, Bennett A, Bothner B, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Muzyczka N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2013. Structure and dynamics of adeno-associated virus serotype 1 VP1-unique N-terminal domain and its role in capsid trafficking. J Virol 87:4974–4984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02524-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleker S, Sonntag F, Kleinschmidt JA. 2005. Mutational analysis of narrow pores at the fivefold symmetry axes of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids reveals a dual role in genome packaging and activation of phospholipase A2 activity. J Virol 79:2528–2540. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2528-2540.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol 72:1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handa A, Muramatsu S, Qiu J, Mizukami H, Brown KE. 2000. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-3-based vectors transduce haematopoietic cells not susceptible to transduction with AAV-2-based vectors. J Gen Virol 81:2077–2084. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-8-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halbert CL, Allen JM, Miller AD. 2001. Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of AAV2 vectors. J Virol 75:6615–6624. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6615-6624.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M, Govindasamy L, Afione S, Kaludov N, Agbandje-McKenna M, Chiorini JA. 2008. Molecular characterization of the heparin-dependent transduction domain on the capsid of a novel adeno-associated virus isolate, AAV(VR-942). J Virol 82:8911–8916. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00672-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mietzsch M, Broecker F, Reinhardt A, Seeberger PH, Heilbronn R. 2014. Differential adeno-associated virus serotype-specific interaction patterns with synthetic heparins and other glycans. J Virol 88:2991–3003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03371-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaludov N, Brown KE, Walters RW, Zabner J, Chiorini JA. 2001. Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity. J Virol 75:6884–6893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6884-6893.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol 80:9093–9103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walters RW, Yi SM, Keshavjee S, Brown KE, Welsh MJ, Chiorini JA, Zabner J. 2001. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J Biol Chem 276:20610–20616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell CL, Vandenberghe LH, Bell P, Limberis MP, Gao GP, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. 2011. The AAV9 receptor and its modification to improve in vivo lung gene transfer in mice. J Clin Invest 121:2427–2435. doi: 10.1172/JCI57367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen S, Bryant KD, Brown SM, Randell SH, Asokan A. 2011. Terminal N-linked galactose is the primary receptor for adeno-associated virus 9. J Biol Chem 286:13532–13540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hahm HS, Broecker F, Kawasaki F, Mietzsch M, Heilbronn R, Fukuda M, Seeberger PH. 2017. Automated glycan assembly of oligo-N-acetyllactosamine and keratan sulfate probes to study virus-glycan interactions. Chem 2:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pillay S, Meyer NL, Puschnik AS, Davulcu O, Diep J, Ishikawa Y, Jae LT, Wosen JE, Nagamine CM, Chapman MS, Carette JE. 2016. An essential receptor for adeno-associated virus infection. Nature 530:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature16465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, Yant SR, Xu H, Kay MA. 2006. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J Virol 80:9831–9836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asokan A, Hamra JB, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Adeno-associated virus type 2 contains an integrin α5β1 binding domain essential for viral cell entry. J Virol 80:8961–8969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00843-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Summerford C, Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ. 1999. αVβ5 integrin: a coreceptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection [see comments]. Nat Med 5:78–82. doi: 10.1038/4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kashiwakura Y, Tamayose K, Iwabuchi K, Hirai Y, Shimada T, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Watanabe M, Oshimi K, Daida H. 2005. Hepatocyte growth factor receptor is a coreceptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. J Virol 79:609–614. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.609-614.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blackburn SD, Steadman RA, Johnson FB. 2006. Attachment of adeno-associated virus type 3H to fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Arch Virol 151:617–623. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Pasquale G, Davidson BL, Stein CS, Martins I, Scudiero D, Monks A, Chiorini JA. 2003. Identification of PDGFR as a receptor for AAV-5 transduction. Nat Med 9:1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzpatrick Z, Leborgne C, Barbon E, Masat E, Ronzitti G, van Wittenberghe L, Vignaud A, Collaud F, Charles S, Simon Sola M, Jouen F, Boyer O, Mingozzi F. 2018. Influence of preexisting anti-capsid neutralizing and binding antibodies on AAV vector transduction. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 9:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thwaite R, Pages G, Chillon M, Bosch A. 2015. AAVrh.10 immunogenicity in mice and humans: relevance of antibody cross-reactivity in human gene therapy. Gene Ther 22:196–201. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De BP, Heguy A, Hackett NR, Ferris B, Leopold PL, Lee J, Pierre L, Gao G, Wilson JM, Crystal RG. 2006. High levels of persistent expression of α1-antitrypsin mediated by the nonhuman primate serotype rh.10 adeno-associated virus despite preexisting immunity to common human adeno-associated viruses. Mol Ther 13:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu C, Busuttil RW, Lipshutz GS. 2010. RH10 provides superior transgene expression in mice when compared with natural AAV serotypes for neonatal gene therapy. J Gene Med 12:766–778. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu Y, Ai J, Gessler D, Su Q, Tran K, Zheng Q, Xu X, Gao G. 2016. Efficient transduction of corneal stroma by adeno-associated viral serotype vectors for implications in gene therapy of corneal diseases. Hum Gene Ther 27:598–608. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang H, Yang B, Mu X, Ahmed SS, Su Q, He R, Wang H, Mueller C, Sena-Esteves M, Brown R, Xu Z, Gao G. 2011. Several rAAV vectors efficiently cross the blood-brain barrier and transduce neurons and astrocytes in the neonatal mouse central nervous system. Mol Ther 19:1440–1448. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang B, Li S, Wang H, Guo Y, Gessler DJ, Cao C, Su Q, Kramer J, Zhong L, Ahmed SS, Zhang H, He R, Desrosiers RC, Brown R, Xu Z, Gao G. 2014. Global CNS transduction of adult mice by intravenously delivered rAAVrh.8 and rAAVrh.10 and nonhuman primates by rAAVrh.10. Mol Ther 22:1299–1309. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albright BH, Storey CM, Murlidharan G, Castellanos Rivera RM, Berry GE, Madigan VJ, Asokan A. 2018. Mapping the structural determinants required for AAVrh.10 transport across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Ther 26:510–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foust KD, Nurre E, Montgomery CL, Hernandez A, Chan CM, Kaspar BK. 2009. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol 27:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zerah M, Piguet F, Colle MA, Raoul S, Deschamps JY, Deniaud J, Gautier B, Toulgoat F, Bieche I, Laurendeau I, Sondhi D, Souweidane MM, Cartier-Lacave N, Moullier P, Crystal RG, Roujeau T, Sevin C, Aubourg P. 2015. Intracerebral gene therapy using AAVrh.10-hARSA recombinant vector to treat patients with early-onset forms of metachromatic leukodystrophy: preclinical feasibility and safety assessments in nonhuman primates. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev 26:113–124. doi: 10.1089/humc.2014.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tardieu M, Zerah M, Husson B, de Bournonville S, Deiva K, Adamsbaum C, Vincent F, Hocquemiller M, Broissand C, Furlan V, Ballabio A, Fraldi A, Crystal RG, Baugnon T, Roujeau T, Heard JM, Danos O. 2014. Intracerebral administration of adeno-associated viral vector serotype rh.10 carrying human SGSH and SUMF1 cDNAs in children with mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA disease: results of a phase I/II trial. Hum Gene Ther 25:506–516. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nam HJ, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Potter M, Byrne B, Salganik M, Muzyczka N, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2011. Structural studies of adeno-associated virus serotype 8 capsid transitions associated with endosomal trafficking. J Virol 85:11791–11799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05305-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie Q, Lerch TF, Meyer NL, Chapman MS. 2011. Structure-function analysis of receptor-binding in adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (AAV-6). Virology 420:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerlach B, Kleinschmidt JA, Bottcher B. 2011. Conformational changes in adeno-associated virus type 1 induced by genome packaging. J Mol Biol 409:427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levy HC, Bowman VD, Govindasamy L, McKenna R, Nash K, Warrington K, Chen W, Muzyczka N, Yan X, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2009. Heparin binding induces conformational changes in adeno-associated virus serotype 2. J Struct Biol 165–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jose A, Mietzsch M, Smith JK, Kurian J, Chipman P, McKenna R, Chiorini J, Agbandje-McKenna M, Jose A, Mietzsch M, Smith JK, Kurian J, Chipman P, McKenna R, Chiorini J, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2018. High resolution structural characterization of a new AAV5 antibody epitope toward engineering antibody resistant recombinant gene delivery vectors. J Virol 91:e01394-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01394-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mietzsch M, Kailasan S, Garrison J, Ilyas M, Chipman P, Kantola K, Janssen ME, Spear J, Sousa D, McKenna R, Brown K, Soderlund-Venermo M, Baker T, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2017. Structural insights into human bocaparvoviruses. J Virol 91:e00261-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kailasan S, Halder S, Gurda B, Bladek H, Chipman PR, McKenna R, Brown K, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2015. Structure of an enteric pathogen, bovine parvovirus. J Virol 89:2603–2614. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03157-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mietzsch M, Penzes JJ, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2019. Twenty-five years of structural parvovirology. Viruses 11:E362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Albright BH, Simon KE, Pillai M, Devlin GW, Asokan A, Albright BH, Simon KE, Pillai M, Devlin GW, Asokan A. 2019. Modulation of sialic acid dependence influences the CNS transduction profile of adeno-associated viruses. J Virol 93:e00332-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00332-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bell CL, Gurda BL, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. 2012. Identification of the galactose binding domain of the adeno-associated virus serotype 9 capsid. J Virol 86:7326–7333. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00448-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao G, Alvira MR, Somanathan S, Lu Y, Vandenberghe LH, Rux JJ, Calcedo R, Sanmiguel J, Abbas Z, Wilson JM. 2003. Adeno-associated viruses undergo substantial evolution in primates during natural infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:6081–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937739100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wright JF. 2008. Manufacturing and characterizing AAV-based vectors for use in clinical studies. Gene Ther 15:840–848. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhong L, Li B, Jayandharan G, Mah CS, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Herzog RW, Weigel-Van Aken KA, Hobbs JA, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N, Srivastava A. 2008. Tyrosine-phosphorylation of AAV2 vectors and its consequences on viral intracellular trafficking and transgene expression. Virology 381:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhong L, Li B, Mah CS, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Cooper M, Herzog RW, Zolotukhin I, Warrington KH Jr, Weigel-Van Aken KA, Hobbs JA, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N, Srivastava A. 2008. Next generation of adeno-associated virus 2 vectors: point mutations in tyrosines lead to high-efficiency transduction at lower doses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:7827–7832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802866105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gurda BL, Raupp C, Popa-Wagner R, Naumer M, Olson NH, Ng R, McKenna R, Baker TS, Kleinschmidt JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2012. Mapping a neutralizing epitope onto the capsid of adeno-associated virus serotype 8. J Virol 86:7739–7751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00218-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suloway C, Pulokas J, Fellmann D, Cheng A, Guerra F, Quispe J, Stagg S, Potter CS, Carragher B. 2005. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J Struct Biol 151:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spear JM, Noble AJ, Xie Q, Sousa DR, Chapman MS, Stagg SM. 2015. The influence of frame alignment with dose compensation on the quality of single particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol 192:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache JP, Verba KA, Cheng Y, Agard DA. 2017. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods 14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ. 2007. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan X, Sinkovits RS, Baker TS. 2007. AUTO3DEM: an automated and high throughput program for image reconstruction of icosahedral particles. J Struct Biol 157:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. 2015. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol 192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Emsley P, Cowtan K. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Gallo Cassarino T, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2014. SWISS-MODEL: modeling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W252–258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carrillo-Tripp M, Shepherd CM, Borelli IA, Venkataraman S, Lander G, Natarajan P, Johnson JE, Brooks CL III, Reddy VS. 2009. VIPERdb2: an enhanced and web API enabled relational database for structural virology. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D436–D442. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. 1996. xdlMAPMAN and xdlDATAMAN: programs for reformatting, analysis and manipulation of biomacromolecular electron-density maps and reflection data sets. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 52:826–828. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995014983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2004. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bartesaghi A, Matthies D, Banerjee S, Merk A, Subramaniam S. 2014. Structure of beta-galactosidase at 3.2-A resolution obtained by cryo-electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:11709–11714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402809111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.DeLano Scientific. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The full and empty AAV8, AAVrh.10, and AAVrh.39 cryo-EM reconstructed density maps and models built for their capsids were deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) with accession numbers EMD-21004/PDB ID 6V10 (AAV8 full), EMD-21010/PDB ID 6V12 (AAV8 empty), EMD-21011/PDB ID 6V1G (AAVrh.10 full), EMD-0663/PDB ID 6O9R (AAVrh.10 empty), EMD-21020/PDB ID 6V1Z (AAVrh.39 full), and EMD-21017/PDB ID 6V1T (AAVrh.39 empty), respectively.