Abstract

Study Design:

This is a retrospective study comparing the diagnosis of spinal implant infection (SII) by peri-implant tissue culture to vortexing-sonication of retrieved spinal implants.

Objective:

We hypothesized that vortexing-sonication would be more sensitive than peri-implant tissue culture.

Summary of Background Data:

We previously showed implant vortexing-sonication followed by culture to be more sensitive than standard peri-implant tissue culture for diagnosing of SII. In this follow-up study, we analyzed the largest sample size available in the literature to compare these two culture methods and evaluated thresholds for positivity for sonicate fluid for SII diagnosis.

Methods:

We compared peri-implant tissue culture to the vortexing-sonication technique which samples bacterial biofilm on the surface of retrieved spinal implants. We evaluated different thresholds for sonicate fluid positivity and assessed the sensitivity and specificity of the two culture methods for the diagnosis of SII.

Results:

A total of 152 patients were studied. With >100 colony forming units (CFU)/10 mL as a threshold for sonicate fluid culture positivity, there were 46 patients with SII. The sensitivities of peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid culture were 65.2% and 79.6%; the specificities were 88.7% and 93.4%, respectively. With >50 CFU/10 mL as a threshold, there were 50 patients with SII. The sensitivities of peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid culture were 68.0% and 76.0%; the specificities were 92.2% for both methods. Finally, with ≥20 CFU/10 mL as a threshold, there were 52 patients with SII. The sensitivities of peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid culture were 69.2% and 82.7%; the specificities were 94.0% and 92.0%, respectively.

Conclusion:

Implant sonication followed by culture is a sensitive and specific method for the diagnosis of SII. Lower thresholds for defining sonicate fluid culture positivity allow for increased sensitivity with a minimal decrease in specificity, enhancing the clinical utility of implant sonication.

Keywords: implant sonification, spinal implant infection

Introduction

Infection complicates 0.7–20% of spinal procedures and is associated with significant morbidity and cost [1–3]. Appropriate surgical and medical management of these infections requires accurate and timely diagnosis. However, diagnosing spinal implant infection (SII) can be a challenge.

With the understanding that the use of peri-implant tissues may lack adequate sensitivity and specificity to diagnose a SII, we previously investigated the utility of a technique which uses a combination of vortexing and sonication to dislodge and disaggregate bacteria in biofilms on the surfaces of retrieved spinal implants followed by culture-based analysis of the resulting sonicate fluid [4]. This technique had previously been shown to be more sensitive than conventional peri-prosthetic tissue culture for the diagnosis of prosthetic knee, hip, shoulder, and elbow infections and has also been used to diagnose breast and cardiac implant associated infections [5–11].

In this follow-up study, we analyzed the largest sample size available in the literature to compare vortexing-sonication of removed spinal implants to peri-implant tissue culture for the diagnosis of SII. We also investigated different threshold levels of sonicate fluid culture positivity to determine their effect on the sensitivity and specificity of sonicate fluid culture in the diagnosis of SII.

Methods

The methodology of this study is similar to that previously reported by our group [4]. Subjects undergoing revision or resection of spinal implants at our institution between June 2007 and February 2016 who had spinal implants sent for sonicate fluid culture were analyzed. Among this cohort, only subjects who had spinal implants submitted for culture as well as 2 or more peri-implant tissue specimens submitted for culture were studied. Subjects were excluded if the implants did not fit in the container or obvious contamination of the implants occurred in the operating room. Cefazolin (or vancomycin in subjects allergic to penicillin) was administered intravenously approximately 30 minutes before incision or after tissue samples were collected. This study was approved by our institution’s IRB, number 09–000808.

In line with our prior study, subjects were classified as having a SII if ≥1 of the following were present: Acute inflammation on histopathologic examination of tissue specimens, intraoperative purulence surrounding the implant, sinus tract communicating with the implant, ≥2 positive peri-implant tissue cultures and positive sonicate fluid cultures of the same organism, or isolation of Staphylococcus aureus from sonicate fluid or peri-implant tissue [4]. Aseptic failure (AF) was defined as implant failure not meting these criteria [4, 8].

In most cases, tissue with the most obvious inflammatory change was submitted for intraoperative frozen section histopathologic evaluation, and preoperative peripheral blood leukocyte count, hemoglobin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels were determined. Microbiologic specimens were processed for culture within 6 hours of collection.

Culture was performed on 2 to 13 peri-implant tissue specimens per patient, as previously described [4, 6]. Each unique colony morphology was identified using routine techniques. Colonies were counted semiquantitatively, per usual clinical practice. Organisms were defined as causative of infection if the same organism was cultured from at least 2 peri-implant tissue specimens.

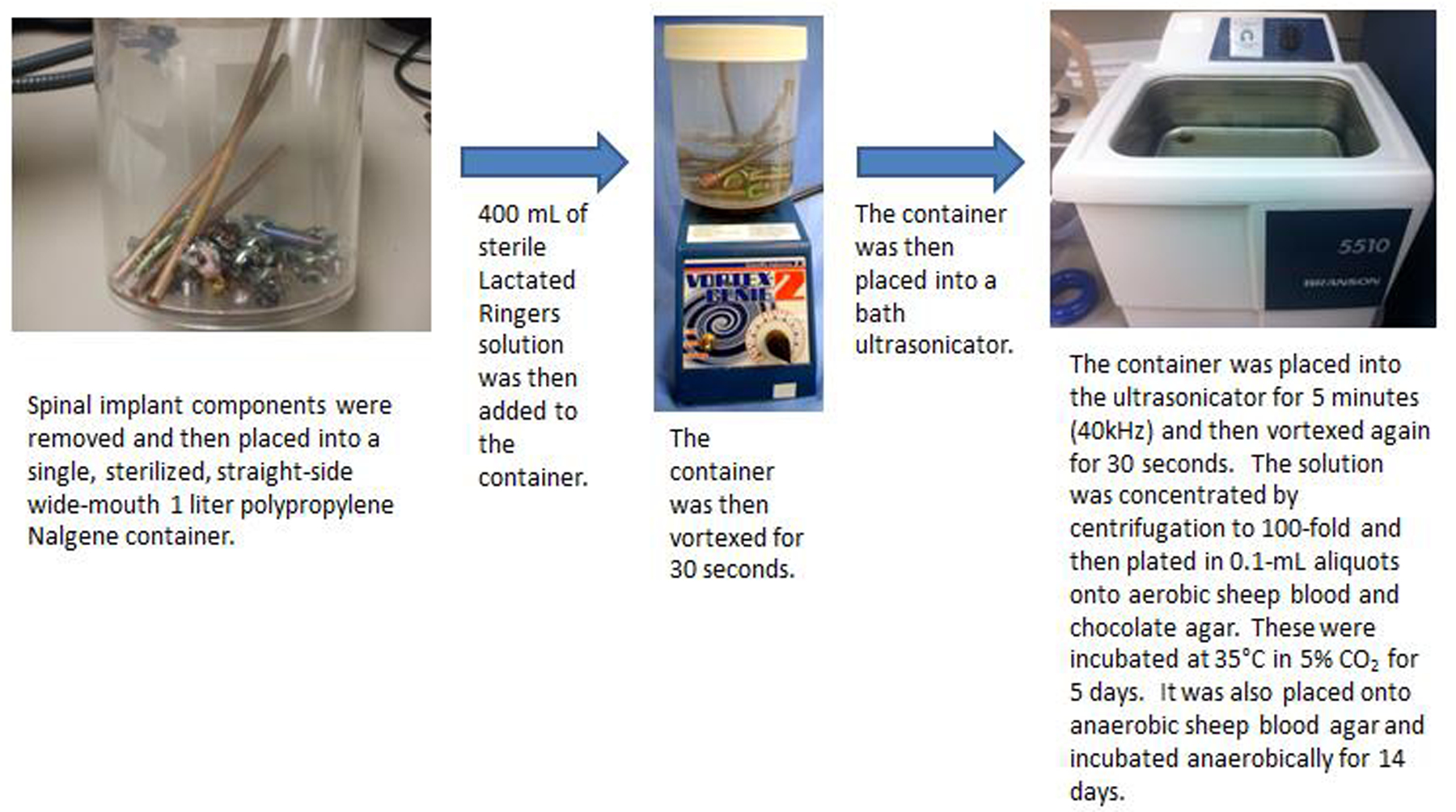

Using sterile technique, implant components were combined into a single sterilized 1L polypropylene container (Nalgene, Lima, OH), to which 400 mL of Ringer solution was added; the container was processed as shown in Figure 1, with sonicate fluid cultured as previously described [6]. In our previous analysis, the cutoff value for sonicate fluid culture positivity for virulent bacteria was set at >100 colony forming units (CFU)/10 mL. In this study, we established three separate groups based on different thresholds of sonicate fluid culture positivity. In Group 1, sonicate fluid cultures were considered positive when >100 CFU/10 mL were isolated. In Group 2, sonicate fluid cultures were considered positive when >50 CFU/10 mL were isolated and in Group 3, sonicate fluid cultures were considered positive when ≥20 CFU/10 mL were isolated. These thresholds were established as our laboratory reports sonicate fluid culture results as <20 CFU/10 mL, 20–50 CFU/10 mL, 51–100 CFU/10 mL, and >100 CFU/10 mL.

Figure 1:

Sonication Procedure. Spinal implants were removed and placed into a sterile solution. They were then vortexed for 30 seconds and placed into an ultrasonicator. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures were then grown as detailed in the figure.

Overall comparisons among the descriptive summaries of clinical characteristics for continuous and categorical outcomes among the groups were made using the Kruskall-Wallis or Chi-Square (or Fischer exact) test, or ANOVA, as appropriate. The sensitivity and specificity of the peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid culture using SII status as an appropriate gold standard were calculated along with 95% exact binomial confidence intervals. The sensitivity and specificity of peri-implant tissue were compared to the sensitivity and specificity of sonicate fluid cultures using McNemar’s tests. P-values less than 0.05 for (2-sided test) were considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed with the SAS statistical software package, version 9.4 (SAS Institute INC., Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 212 subjects were studied, of which 60 were excluded, leaving 152 subjects available for analysis. Twenty four patients were excluded as only sonicate fluid cultures were assessed with no peri-implant tissue cultures performed at the time of implant revision or resection. Twenty three patients were excluded as they had been on antibiotic therapy prior to surgery. Twelve patients were excluded as only 1 peri-implant tissue culture was sent for analysis at the time of surgery. One patient was excluded as their sonicate specimen was mislabeled as a spine culture when it was truly a total hip arthroplasty specimen. In Group 1 in which sonicate fluid cultures were considered positive when >100 CFU/10 mL were isolated, 106 patients had AF and 46 patients had SII. In Group 2, in which sonicate fluid cultures were considered positive when >50 CFU/10 mL were isolated, 102 patients had AF and 50 patients had SII. In Group 3, in which sonicate fluid cultures were considered positive when ≥20 CFU/10 mL were isolated, 100 patients had AF and 52 patients had SII (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Subject Inclusion and Exclusion. Two hundred and twelve subjects were initially identified for inclusion in the study. Sixty subjects were ultimately excluded. The remaining 152 subjects were broken into 3 groups based on 3 separate thresholds for ultrasonicate culture positivity.

The time to implant removal was similar across all groups, with a majority of patients in each group having their implants either revised or resected over 1 year following initial implantation (Group 1: AF 77.7% vs. SII 65.0% p=0.14; Group 2: AF 77.8% vs. SII 66.7% p=0.15; Group 3: AF 77.3% vs. SII 68.0% p=0.22). There were significantly more hardware resections performed in the SII group (Group 1: AF 30.2% vs. SII 78.3%, p<0.0001; Group 2: AF 28.4% vs. SII 78.0%, p<0.0001; Group 3: AF 28.0% vs. SII 77.0%, p<0.0001). Inflammatory markers were significantly higher in the SII cohort when compared to the AF cohort across all groups (Group 1 ESR: AF 16.3 vs. SII 44.1, p=0.0003; Group 2 ESR: AF 16.5 vs. SII 42.9, p=0.0005; Group 3 ESR: AF 16.8 vs. SII 41.7, p=0.0008; Group 1 CRP: AF 13.9 vs. SII 60.2, p=0.002; Group 2 CRP: AF 14.2 vs. SII 58.4, p=0.003; Group 3 CRP: AF 14.4 vs. CRP 56.8, p=0.004). Additional demographic and clinical characteristics and laboratory data are shown in Table 1.

In Group 1, the sensitivities of tissue and sonicate fluid culture were 65.2% [95% confidence interval (CI), 51.4%−79.0%] and 69.6% (95% CI, 56.3%−82.9%) (p=0.59). In Group 2, the sensitivities of tissue and sonicate fluid culture were 68.0% (95% CI, 55.1%−80.9%) and 76.0% (95% CI, 64.2%−87.8%) (p=0.28). In Group 3, the sensitivities of tissue and sonicate fluid culture were 69.2% (95% CI, 56.7%−81.8%) and 82.7% (95% CI, 72.4%−93%) (p=0.07). Specificities for tissue and sonicate fluid culture, respectively, in groups 1, 2 and 3, were 88.7% (95% CI, 82.6%−94.7%) and 93.4% (95% CI, 88.7%−98.1%) (p=0.25); 92.2% (95% CI, 86.9%−97.4%) and 92.2% (95% CI, 86.9%−97.4%) (p=0.99); and 94.0% (95% CI, 89.3%−98.6%) and 92.0% (95% CI, 86.7%−97.3%) (p=0.59) (Table 2).

Sonicate fluid culture was positive in 7 instances in Group 1 without a concordant positive peri-implant culture. The organisms isolated from these cultures were coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species (CNS), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Finegoldia magna. In two instances, one (but not two) peri-implant tissue culture specimen demonstrated concordant microbiology. In Group 2 there was one patient with positive sonicate fluid cultures without positive peri-implant tissue cultures. This patient grew Cutibacterium acnes and F. magna, each at 51–100 CFU/10 mL; one of three tissue culture specimens was positive for C. acnes. In Group 3, there were two instances of positive sonicate fluid cultures without positive peri-implant tissue cultures. One patient’s sonicate fluid grew CNS at 20–50 CFU/10 mL and another grew C. acnes at 20–50 CFU/10 mL. Neither patient had positive peri-implant tissue cultures.

Overall, there were 4 patients who had positive peri-implant tissue cultures without positive sonicate fluid cultures. In one case, 9 of 13 peri-implant tissue cultures were positive for Mycobacterium chelonae/abscessus complex and the sonicate fluid demonstrated no growth. In another case, 3 of 4 peri-implant tissue cultures were positive for Streptococcus mutans and the sonicate fluid demonstrated no growth. One patient had 2 of 6 peri-implant tissue cultures positive for C. acnes and Enterobacter cloacae and sonicate fluid culture grew E. cloacae at <20 CFU/10 mL. Another patient grew CNS and C. acnes from 2 of 3 peri-implant tissue specimens and sonicate fluid culture grew C. acnes at <20 CFU/10 mL. Two patients had positive peri-implant tissue cultures with positive sonicate fluid analysis when alternate thresholds were used. One patient grew Staphylococcus epidermidis from 3 of 3 peri-implant tissue specimens and sonicate fluid culture also grew S. epidermidis at 51–100 CFU/10 mL. Finally, one patient grew CNS from 3 of 4 peri-implant tissue specimens and also grew CNS at 20–50 CFU/10 mL from sonicate fluid culture.

Using these two techniques, the bacterial organisms detected in subjects with SII are shown in Table 3. In Group 1, C. acnes was isolated from 23.9% (11/46) and 17.4% (8/46) of positive peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid cultures, respectively; S. aureus was isolated from 19.6% (9/46) and 23.9% (11/46) of positive peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid cultures, respectively; and CNS was isolated from 17.4% (8/46) and 10.9% (5/46) of positive peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid cultures, respectively. When the threshold for sonicate culture positivity was lowered, Groups 2 and 3 saw an increase in the number of positive C. acnes cultures. Amongst all patients with AF, C. acnes was the most common organism isolated from both peri-implant tissue and sonicate fluid cultures (Table 3).

Discussion

Culture of material dislodged from the surface of spinal implants is as sensitive and specific as peri-implant tissue culture for microbiologic diagnosis of SII. Setting lower thresholds for a positive sonicate culture increased the sensitivity of the test without a significant decrease in its specificity.

Spinal implant infections are often difficult to diagnose and challenging to treat. Specifics regarding the trials and tribulations inherent in revision surgery for implant associated spine infections and their associated outcomes have been previously reported [12]. Based on these results, early-onset spinal infections with symptoms occurring within 30 days of implantation are routinely managed with implant retention; implant removal is pursued in late-onset infections in which symptoms occur after 30 days or more after implantation [12]. Obtaining a culture in the setting of a post-operative infections remains of paramount clinical importance and is particularly difficult in the setting of SIIs as many of the organisms commonly implicated in spinal implant infections form biofilms [2]. Atkins et al., in an assessment of prosthetic infections with a suspected biofilm, found that peri-implant tissue cultures may not provide the requisite sensitivity to accurately diagnose a prosthetic joint infection [13]. Given the importance of biofilm formation in the development of an implant infection, culture methods specifically targeted towards biofilm identification, such as vortexing and sonication, have become popular. The process of vortexing and sonication of medical implants dislodges bacteria that have created a biofilm and subsequent culture allows for their identification and ultimate treatment. In one of the initial studies to report on vortexing and sonication, our group found that sonicate cultures were more sensitive than conventional periprosthetic tissue cultures for the microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic hip and knee infection [8]. Larsen et al., in a systematic literature review assessing various periprosthetic culture methods, found that sonicate fluid was the most sensitive and specific technique available [14]. In line with these studies, several authors have shown the superior sensitivity and specificity of vortexing and sonication with many different types of implants [5, 6, 15–19]. However, little has been written about the use of vortexing and sonication for the diagnosis of SII. Plaass et al. used the process of vortexing and sonication to investigate bacterial colonization of spinal implants in children undergoing growth-retaining spinal implant placement for management of early onset scoliosis. Their results demonstrated that the process of vortexing and sonication can be successfully used to detect bacterial colonization on spinal implants [20]. Our group previously compared sonicate cultures to peri-implant tissue cultures and found sonicate cultures to be more sensitive in the diagnosis of SII [4]. The results of our current study further emphasize that sonicate cultures remain a useful means of diagnosis SII.

As mentioned, many of the organisms implicated in SII have a predilection for biofilm formation [2]. Earlier series reporting on SII identified S. aureus, CNS, and enterococci as common organisms responsible for SII [1, 3]. Recently, C. acnes has been identified as an important cause of SII, particularly in late-onset infections [21, 22]. Kasliwal et al. report that many of the common bacteria implicated in SII, including S. aureus, CNS, and C. acnes, form biofilms [2]. Interestingly, this distribution of organisms is similar to the culture data we obtained from our patient cohort, with C. acnes, S. aureus, and CNS being the most common organisms found. As these organisms commonly form biofilms, it is advantageous to use culture methods such as vortexing and sonication that particularly target biofilms. A previous study from our institution investigating the management of spinal implant infections found a slightly different distribution of microorganisms, with S. aureus, polymicrobial infections, gram negative bacilli, and CNS comprising the predominant infectious species [12]. Sonicate cultures were not used in that study, thus emphasizing their utility in potentially identifying a spectrum organisms that may otherwise be missed when managing SII.

In our study we also evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of sonicate culture at various thresholds of sonicate positivity. A previous study by Rothenberg et al. performed a similar analysis for sonicate cultures in the setting of total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty infections [17]. Their analysis showed that sensitivity was maximized at 5 CFU/10 mL and that overall, sonicate cultures were more sensitive and as specific as both synovial fluid cultures and tissue cultures [17]. During our previous study, we had initially utilized ≥5 CFU as a cutoff for sonicate culture positivity in line with previous work from our institution and in line with the work of Rothenberg et al [4, 8, 17]. However, our sonicate methodology changed during our initial study to include a concentrating step that leads to a 20-fold concentration increase of the sonicate fluid [4]. Thus, we increased our threshold to >100 CFU/10 mL [4]. In this current study, we assessed three different thresholds: >100 CFU/10 mL, >50 CFU/10 mL, and ≥20 CFU/10 mL, as these are the various levels reported by our institution’s laboratory on the concentrated sonicate fluid. Cultures that return with <20 CFU/10 mL are considered clinically insignificant. Our study found that the sensitivity of sonicate fluid culture is maximized at ≥20 CFU/10 mL with minimal change in the specificity of the test. While the differences between peri-implant tissue culture and sonicate culture were not statistically significant, sonicate fluid culture tended to be more sensitive, particularly with a threshold of ≥20 CFU/10 mL. Given these results, we recommend considering sonicate culture results of ≥20 CFU/10 mL as representing true infections.

Our study has several limitations. First, while the database of patients undergoing implant sonication is maintained prospectively, our study is retrospective in design and is thus subject to biases inherent to this study design. Furthermore, not all information is available for each patient. For instance, some patients did not have tissue samples sent for intraoperative pathology and in others there is no comment as to whether there was purulent fluid present and/or a sinus tract present. These are key components of the diagnostic criteria we utilized for the diagnosis of SII and thus the absence of this data in some patients could have led us to miss some infections. Additionally, we used positive peri-implant tissue cultures and positive sonicate fluid culture as components of the diagnostic criteria for SII. We kept these in the diagnostic criteria as they had been used in the previous study and we sought to make the two studies as comparable as possible [4]. Moreover, while there are standardized definitions for peri-prosthetic infections involving total hip or total knee arthroplasty, there are no standardized definitions for spinal implant infections. Thus, we have created a definition based on studies of different implant systems. Another limitation is that there was not a uniform number of cultures sent for each patient which may influence the diagnostic parameters of the test. Finally, we have recently demonstrated that tissue culture in blood culture bottles can increase culture sensitivity [23]. This was not used in the current study; future studies should evaluate this approach for SII and compare the performance of it to sonicate fluid culture.

In conclusion, we found that sonicate fluid cultures were as sensitive and specific as peri-implant tissue cultures for diagnosis of SII. Sonicate fluid cultures tended to be more sensitive as the threshold levels evaluated decreased, with sonicate fluid culture sensitivity maximized at a threshold of ≥20 CFU/10 mL. Based on our analysis, we therefore recommend the use of 20 CFU/10 mL as a sonicate culture threshold for diagnosis of SII.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health (award number R01AR056647) funds were received in support of this work.

No relevant financial activities outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

The device(s)/drug(s) is/are FDA-approved or approved by corresponding national agency for this indication.

References

- 1.Gerometta A, Rodriguez Olaverri JC, Bitan F. Infections in spinal instrumentation. Int Orthop 2012;36:457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasliwal MK, Tan LA, Traynelis VC. Infection with spinal instrumentation: Review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4(Suppl 5):S392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schimmel JJ, Horsting PP, de Kleuver M, et al. Risk factors for deep surgical site infections after spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1711–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampedro MF, Huddleston PM, Piper KE, et al. A biofilm approach to detect bacteria on removed spinal implants. Spine. 2010;35:1218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi H, Oethinger M, Tuohy MJ, et al. Improved detection of biofilm-formative bacteria by vortexing and sonication: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1360–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Cofield RH, et al. Microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic shoulder infection by use of implant sonication. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1878–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieger UM, Pierer G, Lüscher NJ, et al. Sonication of removed breast implants for improved detection of subclinical infection. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33:404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, et al. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:654–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tunney MM, Patrick S, Curran MD, et al. Detection of prosthetic hip infection at revision arthroplasty by immunofluorescence microscopy and PCR amplification of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tunney MM, Patrick S, Gorman SP, et al. Improved detection of infection in hip replacements. A currently underestimated problem. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:568–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohacek M, Weisser M, Kobza R, et al. Bacterial colonization and infection of electrophysiological cardiac devices detected with sonication and swab culture. Circulation. 2010;121:1691–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowalski TJ, Berbari EF, Huddleston PM, et al. The management and outcome of spinal implant infections: Contemporary retrospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:913–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkins BL, Athanasou N, Deeks JJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of criteria for microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic-joint infection at revision arthroplasty. The OSIRIS Collaborative Study Group. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2932–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen LH, Lange J, Xu Y, et al. Optimizing culture methods for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections: a summary of modifications and improvements reported since 1995. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(Pt 3):309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniar HH, Wingert N, McPhillips K, et al. Role of sonication for detection of infection in explanted orthopaedic trauma implants. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30:e175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliva A, Pavone P, D’Abramo A, et al. Role of sonication in the microbiological diagnosis of implant-associated infections: Beyond the orthopedic prosthesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;897:85–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothenberg AC, Wilson AE, Hayes JP, et al. Sonication of arthroplasty implants improves accuracy of periprosthetic joint infection cultures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1827–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tani S, Lepetsos P, Stylianakis A, et al. Superiority of the sonication method against conventional periprosthetic tissue cultures for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vergidis P, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Sanchez-Sotelo J, et al. Implant sonication for the diagnosis of prosthetic elbow infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:1275–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plaass C, Hasler CC, Heininger U, et al. Bacterial colonization of VEPTR implants under repeated expansions in children with severe early onset spinal deformities. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bemer P, Corvec S, Tariel S, et al. Significance of Propionibacterium acnes-positive samples in spinal instrumentation. Spine. 2008;33:E971–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hahn F, Zbinden R, Min K. Late implant infections caused by Propionibacterium acnes in scoliosis surgery. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:783–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Q, Karau MJ, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, et al. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of periprosthetic tissue culture in blood culture bottles to that of prosthesis sonication fluid culture for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection (PJI) by use of Bayesian latent class modeling and IDSA PJI criteria for classification. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:pii: e00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.