To the Editor:

The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease it causes, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), are the cause of the current pandemic.1 At present, no drug has been proven to be effective for the treatment of COVID-19 and no vaccine is available. We report the first case of a Japanese patient with severe COVID-19 pneumonia who had a favorable outcome after receiving treatment with ciclesonide, an anti-inflammatory drug.

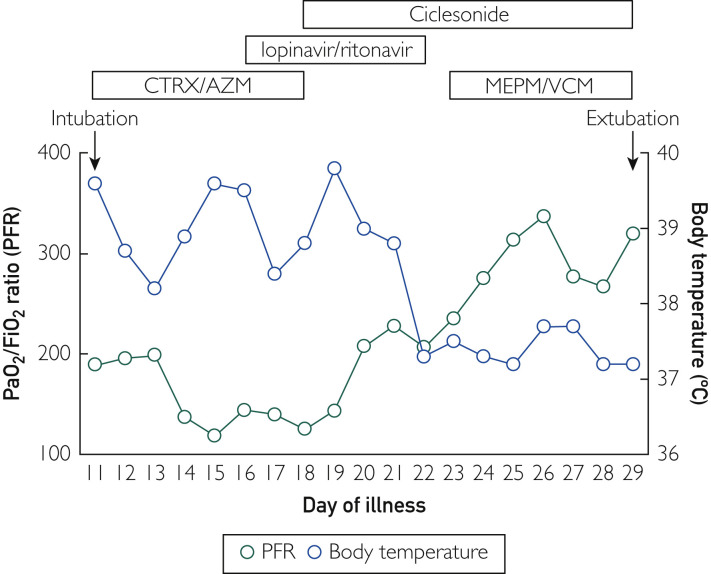

A 64-year-old Japanese man consulted a local physician for fever lasting 3 days and was initially treated with azithromycin with a presumptive diagnosis of pneumonia. However, 3 days later (illness day 6), he was referred to another hospital because the fever persisted. On illness day 9, the patient began minocycline treatment. However, his respiratory condition worsened. On illness day 11, he was referred to the Yokohama City University Hospital. The patient had a history of medicated hypertension. Upon arrival at our hospital, the patient’s vital signs were as follows: Glasgow Coma Scale, 15; blood pressure, 140/100 mm Hg; temperature, 39.4°C; pulse, 104 beats/min; respiratory rate, 36 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation with a non-rebreather mask (15 L/min), 96%. Lung auscultation was unremarkable. Although his C-reactive protein level was high (12.45 mg/L), the patient’s blood cell count was within the reference range (5800 cells/μL), with a relatively high percentage of neutrophils (74%) and a low percentage of lymphocytes (15.6%). Chest radiography performed the same day revealed diffuse infiltrates bilaterally, and chest computed tomography (CT) scans revealed multiple peripherally dominant ground-glass opacities with some infiltrating shadows. These findings were similar to those of other patients with COVID-19 seen at our hospital. The patient was a taxi driver and reported contact with passengers who had a cough. Coronavirus disease 2019 was strongly suspected, and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was ordered. The patient was immediately admitted to an intensive care unit with an infection control zone, in which he was intubated and ventilated to control hypoxia. Our treatment strategy was based on the World Health Organization recommendations for supportive care, including oxygen therapy, fluid management, and antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections (ceftriaxone and azithromycin).2 On hospital day 5 (illness day 15), the aspirated sputum tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR analysis. However, we still strongly suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection because the white blood cell count was normal, the C-reactive protein levels remained elevated, the CT findings were consistent with COVID-19, and oxygenation did not improve. On hospital day 6 (illness day 16), the aspirated sputum tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Oxygenation disturbances and chest radiographic changes persisted, and lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r; total dose lopinavir 800 mg/ritonavir 200 mg per day) was prescribed. However, the respiratory status did not improve. Therefore, on hospital day 8 (illness day 18), we prescribed ciclesonide inhalant (400 μg/d) as an anti-inflammatory drug for peripheral inflammatory lesions. By the next day (illness day 19), oxygenation improved, and the patient was weaned gradually from the ventilator. Finally, on hospital day 19 (illness day 29), he was extubated (Figure ). Since then, his respiratory condition remained stable, and he was discharged home on hospital day 34 (illness day 44) after a negative PCR test. Chest radiographs of patients with early-stage COVID-19 may reveal no severe abnormalities in mild or severe disease conditions, whereas CT scans reveal peripheral ground-glass opacities in severe cases. These findings seem specific to COVID-19.3 Coronavirus disease 2019 differs from other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome and viral pneumonias in that it has fewer interstitial changes. Rather, peripheral alveolar injury is more associated with COVID-19. Indeed, no increase in markers of interstitial disorders (such as Krebs von den Lungen-6 and pulmonary surfactant protein D and no decrease in lung compliance were observed in COVID-19. Our patient presented similar features, and we suspected COVID-19, despite the first PCR test being negative. Although previous treatment with LPV/r failed to improve oxygenation, treatment with ciclesonide coincided with a positive outcome. In fact, nasopharyngeal swab specimens before and after LPV/r administration were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Figure.

Time course of respiratory function and clinical features in the presented case. AZM = azithromycin; CTRX = ceftriaxone; MEPM = meropenem; PFR = PaO2/FiO2 ratio; VCM = vancomycin.

Ciclesonide is an inhaled steroid drug that suppresses asthmatic attacks by decreasing airway hyperresponsiveness as well as the immediate and delayed forms of pulmonary resistance induced by the inhalation of antigens.4 Ciclesonide suppresses the production of tumor necrosis factor-α and cytokines such as interleukin 4 and interleukin 5 and inhibits eosinophil infiltration into the respiratory tract.5 Ciclesonide is a locally activated drug that is converted into the active metabolite desisobutyryl ciclesonide by hydrolase esterase after inhalation. It binds to the glucocorticoid receptor and produces potent anti-inflammatory effects. Furthermore, desisobutyryl ciclesonide reversibly binds to a fatty acid to form a fatty acid conjugate, leading to protraction retention in lung tissue; as an aerosol, it has a high percentage of fine particles that can reach the peripheral airways, with a good lung penetration rate of approximately 52%. Ciclesonide has low systemic adverse effects.4 Chest CT scans, blood tests, and lung compliance results suggest that the main site of inflammation may be the peripheral alveoli.

In conclusion, we report a case of severe COVID-19 pneumonia that was diagnosed correctly on the basis of typical chest CT findings and other clinical features, with a favorable outcome. Our findings suggest that ciclesonide inhalant may improve the respiratory status in severe COVID-19 pneumonia and is worthy of further study in clinical trials.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID-19 disease is suspected. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected

- 3.Ng M.Y., Lee E., Yang J. Imaging profile of the COVID-19 infection: radiologic findings and literature review. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020;2(1) doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deeks E.D., Perry C.M. Ciclesonide: a review of its use in the management of asthma [published correction appears in Drugs. 2008;68(15):2162] Drugs. 2008;68(12):1741–1770. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868120-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoeck M., Richard R., Hochhaus G. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of the new glucocorticoid ciclesonide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309(1):249–258. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]