Abstract

The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is placing a huge strain on health systems worldwide. Suggested solutions like social distancing and lockdowns in some areas to help contain the spread of the virus may affect special patient populations like those with chronic illnesses who are unable to access healthcare facilities for their routine care and medicines management. Retail pharmacy outlets are the likely facilities for easy access by these patients. The contribution of community pharmacists in these facilities to manage chronic conditions and promote medication adherence during this COVID-19 pandemic will be essential in easing the burden on already strained health systems. This paper highlights the pharmaceutical care practices of community pharmacists for patients with chronic diseases during this pandemic. This would provide support for the call by the WHO to maintain essential services during the pandemic, in order to prevent non-COVID disease burden on healthcare systems particularly in low-and middle-income countries.

Keywords: COVID-19, Chronic diseases, Medication adherence, Community pharmacists, Pharmaceutical care, LMICs

Highlights

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic is putting a huge strain on healthcare systems worldwide.

-

•

Patients with chronic diseases have challenges accessing health facilities for their routine care.

-

•

Community pharmacists can support in medicines management and promote medication adherence.

-

•

Contributions from community pharmacists will help maintain essential services during the pandemic.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is putting a huge strain on healthcare systems worldwide.1 Several developed countries such as the United States of America, United Kingdom, Italy and Spain have had to recruit retired health personnel to help battle the infections. Countries like the United States have contracted car and weapon manufacturers to provide ventilators for affected patients in need of them and to help fight the pandemic in the nation. Hospitals in many affected countries are overburdened and in Italy for example, it was projected that approximately 80% of ICU beds was going to be occupied by patients affected by COVID-19 before April 2020.2 In line with the challenge that this pandemic poses on healthcare systems worldwide, the WHO in recognizing how fragile many of the world's health systems and services were, proposed guidelines for countries to maintain essential health services throughout the pandemic period.3

Healthcare systems in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) are especially challenged because of the effect this pandemic will have on the already weak health systems in these countries. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems in LMICs faced considerable challenges in providing high-quality, affordable and universally accessible care.4 , 5 These health systems had limited financial resources, inadequate health personnel and unavailable medications.6, 7, 8, 9

Again, inequitable health access within LMICs may be further widened by the COVID-19 pandemic. The socio-economic gap together with poor quality access to health care has become even more glaring in these times. Persons of higher socio-economic standing are more likely to have access to quality health information and medications for chronic health management, given the current challenges with health care personnel, facilities and essential medicines. Chronic diseases which are often managed poorly in persons of low socio-economic standing is going to be further poorly managed and health outcomes can be projected to get worse. For patients who prior to the pandemic could not afford prescription refills and healthy lifestyle adjustments, a deterioration of their condition as a result of poor health accessibility may be imminent. Thus in the face of this global COVID-19 pandemic, although some persons with high socio-economic standing may struggle with keeping up good health behaviors and medication adherence, the projection for persons with low socio-economic status may be rather dire.10

Impact of COVID-19 on chronic disease medication and adherence

Prior to the incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic, LMICs had a double disease burden of chronic infectious and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, hepatitis, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic pulmonary diseases and mental illnesses.11

Patients with chronic diseases are at a higher risk of threat from the pandemic as the COVID-19 is best combatted by a strong immune system. Yet, chronic diseases like HIV, diabetes and kidney diseases are immunosuppressing, making patients more vulnerable to infections with difficulties in management.12, 13, 14 While stress and anxiety are normal reactions during crisis situations,15 the negative impact of COVID-19 outbreak may affect the clinical outcomes of patients with chronic conditions like mental illness and cardiovascular diseases whose development and management are linked to stress and anxiety.16

In the face of the current pandemic, many countries have had to make tough decisions in order to safeguard its people. These decisions include lockdowns and restrictions on people's movement and mobilization of health personnel to the frontline of the COVID-19 infection. This may be a major problem for patients with chronic diseases requiring revisits, follow-ups, check-ups and prescription refills since access to health facilities and their attending physicians may be denied. Also, the increased likelihood of being infected at hospitals has forced most patients to avoid their health facilities for physician consultations.

There is also unconfirmed information on the health benefits of some products for either preventing or treating COVID-19 in some media outlets and this has caused a surge in unsafe self-medication habits of some over-the-counter medications. In some reports, patients have also relied on community pharmacies for their medication needs which should be available for them.17

Unfortunately, LMICs often rely heavily on pharmaceutical imports and the impact of the pandemic may be felt when essential medicines are unavailable and inaccessible to meet the needs of all, especially those with chronic diseases. The global shut down worldwide has led to fewer imports and exports and most pharmaceutical manufacturing firms have shifted their focus to the production of medicines and medical equipment targeted at the fight against COVID-19 in their nations. There seems to be a shift in the restrained import of pharmaceuticals towards battling the current COVID-19 pandemic, thus leaving a huge gap for pharmaceutical imports that target other chronic diseases. This focus by pharma industries will disadvantage LMICs due to the rather vulnerable and inadequate pharmaceutical manufacturing capacities in these countries to meet their general pharmaceutical needs and those for chronic diseases. With limited supply to meet the increased demand created, the market values of medicines for chronic diseases have escalated, making them unaffordable for several patients in LMICs who require them.

In addition to ensuring that these medicines are available, chronic diseases rely heavily on linear adherence patterns for adequate therapeutic outcomes18 and this needs to be emphasized especially during this COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, persons living with HIV require optimal adherence to their medications to ensure better immunity, viral suppression and treatment success, despite the stress and risk of infection.

For patients with diabetes, strict adherence to medications maintain good glycemic control and prevent complications such as diabetic ulcers and increased blood pressure which further compromise their chances of survival if infected with COVID-19. In general, favorable therapeutic outcomes across many chronic disease states will be achieved when optimal medication adherence levels are maintained.

Unfortunately, the pandemic has left many in fear and with high stress levels.19 While many people struggle to cope with the constant news of the spread and effects of COVID-19 on their media channels, they do not have adequate forms of social support to manage this stress as a result of lockdowns and self-isolation. Yet, the negative effects of stress on disease outcomes and medication adherence have been documented.20, 21, 22 The psychological impact of this pandemic might leave many patients with chronic diseases with little hope of improving their health outcomes, thereby decreasing adherence and perhaps eroding health gains made prior to the pandemic.23

Pharmaceutical care and chronic disease management

Positive health outcomes for patients with chronic diseases have been attributed to pharmaceutical care interventions and this has been consistently reported in literature.18 , 24 Pharmaceutical care interventions aim to optimize medicines utilization for improved therapeutic outcomes.25 These interventions have been reported to save lives and improve patient quality of life26 and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, this role is relevant in augmenting efforts being made by other members of the healthcare team to ensure patient safety and wellbeing.

Although different practice models relate to pharmacy, the concept of pharmaceutical care was proposed and instituted in the mid-1970s to represent general services in patient care where the patient is the primary beneficiary of the actions by pharmacist.27 The role of pharmaceutical care is significant for people with chronic illnesses and is particularly relevant during this COVID-19 pandemic period where many people have various medicines-related concerns. The concept has also been relevant for community practice where services and functions of community pharmacists in promoting and supporting rational medicines use and counseling is imperative.28

In providing pharmaceutical care during the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus of community pharmacists will be on the prevention, identification and/or resolution of drug therapy problems for patrons to their facility. Community pharmacists are ideally positioned for this role because they are the most accessible group of health practitioners during this COVID-19 pandemic to address the substantial issues of inappropriate use of and promote rational use of medicines to people in the community as well as to special populations like patients with chronic conditions.29 , 30 Some pharmaceutical care practices that have been effective in improving patient outcomes for a number of chronic diseases includes the provision of appropriate drug information and counseling on chronic medications, making essential medicines available, addressing polypharmacy and medication safety concerns, assessing medication needs, promoting adherence and providing follow-up services.31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36

Pharmaceutical care and chronic disease management during COVID-19 pandemic

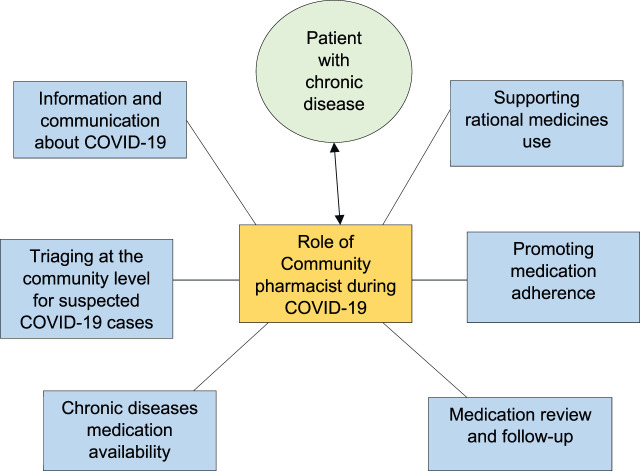

The pharmaceutical care practices of community pharmacists for patients with chronic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic are outlined (Fig. 1 ):

Fig. 1.

Role of community pharmacists during COVID-19 pandemic.

Information and communication about COVID-19

Most countries have been forced to lockdown their major cities and restrict movement within such cities. This restraint has led to many patients relying on community pharmacies for their medication needs and health information.37 Patients with chronic diseases may want to know what to do with their management and medicines during this pandemic. While community pharmacists play key roles in educating patients on preventive measures and the pandemic in general, providing adequate health information on chronic diseases and its management will directly address the concerns of patients in this category who may be confused and worried about their health. These patients may also have questions about medicines to take during this period and the community pharmacists can also serve as “information verification hubs” to clarify the various remedies being advertised on media platforms for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Again, in meeting the task of maintaining needed essential services, community pharmacists need to engage their clients in frequent transparent communications especially with people with chronic conditions to identify their medication needs and provide support appropriately. A strong community engagement will also ensure trust in the health system by patients who will be assured of continuity of health services to meet their essential needs at the community level without having to risk being infected in health facilities. This is also important to ensure that people continue to seek care when appropriate and have it available when needed.

Triaging at the community level for suspected COVID-19 cases

As people with chronic diseases and other ailments report to community pharmacies for non-COVID-19 specific health needs, community pharmacists can assist to identify suspected cases to avoid further community spread. By following laid down protocols, community pharmacists can assist to detect and prevent the spread of the pandemic within communities. For instance, the Community Practice Pharmacists Association of the Pharmaceutical Society of Ghana, has communicated some guidelines to help community pharmacists to triage and report suspected cases of COVID-19 to district health management teams. The proximity to community pharmacists become crucial in the triaging diseases of common occurrence with similar COVID-19 symptoms for appropriate assessment and referral of suspected cases.

Chronic diseases medication availability

In an attempt to promote continuity of medication supply and accessibility to meet the demands of persons with chronic diseases, while promoting social distancing and self-isolation during the pandemic, community pharmacies can employ mobile delivery and courier services to promote door-step prescription refills and other non-prescription supplies. This is to increase medication availability within these times while preventing spread of COVID-19 to vulnerable patient groups. Pharmacists are also collaborating amongst themselves on social platforms to source medications for patients. This does not only enhance availability to medications for patients in need but reduces social interaction of vulnerable chronic disease patients to the pandemic.

Supporting rational medicines use

Although there are no approved specific medicines to prevent or treat COVID-19, social media and other information channels have been flooded with claims of potential remedies for the virus. The community pharmacy will therefore be the most patronized health facility for people to either seek for or verify these recommended therapies. Examples of these popular remedies include hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, preparations with high doses of vitamin C, garlic capsules, lemon tinctures and apple cider vinegar. Community pharmacists are thus tasked with the role of providing information on the authenticity of these claims to promote rational use of medicines. For patients with chronic illnesses especially, who are likely to be taking their prescription drugs, wrongful uptake of information translating into irrational use of these other social opinionated remedies might lead to drug interactions with their routine chronic medications.38 In addition, the proper use of over-the-counter medications for managing simple ailments of common occurrence in patients with chronic illness also need to be monitored by community pharmacists. By playing their traditional roles of counseling patients on their medications, the contribution of community pharmacists in supporting rational use of medicines during this COVID-19 pandemic will be emphasized.

Promoting medication adherence

Reiterating the need for patients with chronic disease to adhere to their medication regimen has been emphasized by community pharmacists, with evidence of improved outcomes from their interventions.39 In this era of lockdowns and restricted movements, pharmacists can apply technology to remind patients of their medications and lifestyle regimen in order to enhance adherence.40 By utilizing phone calls, SMS text messaging and some social media platforms, pharmacists can constantly interact with their patients to emphasize the need for adherence to their medications and lifestyle habits especially within this pandemic. In some instances, courier services could be used for doorstep deliveries of essential medicines and prescription refills, but in such instances, strict consideration for all anti COVID safety protocols should be adhered to.

Medication review and follow-up

As the pandemic continues to extend, the widespread demand on physicians has led to the postponement of routine patient reviews and hospital visits for patients with chronic diseases. Patients who would have required changes to their medications have been left with old prescriptions to refill and patients who required minor procedures may require medications to stabilize their condition until the procedure can be carried out. Patients affected will have to receive continuous supply of prescription medications and this is where the community pharmacists can be entrusted with the responsibility using their judgement to review such prescriptions and provide appropriate medication review management. For instance, patients on opioid analgesics may have their prescription reviewed by the community pharmacist to prevent tolerance and addiction. The roles and practices of community pharmacists may evolve after the COVID-19 pandemic to embrace more prominent aspects of pharmaceutical care and medicines management.

Conclusion

As the world concentrates on containing and delaying the spread of the COVID-19, many health professionals have been burdened with this task and healthcare systems are challenged. Amid this focus, healthcare systems may miss out on patients with chronic diseases whose management may worsen with the pandemic. The contribution of community pharmacists in managing chronic conditions and promoting medication adherence while other health personnel battle the COVID-19 pandemic at the frontline is key to easing the disease burden on health systems. This will provide support for the call by the WHO to maintain essential services in order to prevent non-COVID disease burden on already strained health systems especially in LMICs.

Author's contributions

All authors were involved in all aspects of the commentary, including conceptualization, writing and review of manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

None declared.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Legido-Quigley H., Asgari N., Teo Y.Y. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10227):848–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidelines to Help Countries Maintain Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic. World Health Organization Department of Communications; 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-03-2020-who-releases-guidelines-to-help-countries-maintain-essential-health-services-during-the-covid-19-pandemic [press release] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agampodi T.C., Agampodi S.B., Glozier N., Siribaddana S. Measurement of social capital in relation to health in low and middle income countries (LMIC): a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGregor S., Henderson K.J., Kaldor J.M. How are health research priorities set in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published reports. PloS One. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108787. e108787-e108787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adam T., de Savigny D. Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Pol Plann. 2012;27(suppl_4):iv1–iv3. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovacs S., Hawes S.E., Maley S.N., Mosites E., Wong L., Stergachis A. Technologies for detecting falsified and substandard drugs in low and middle-income countries. PloS One. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090601. e90601-e90601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves A., Gourtsoyannis Y., Basu S., McCoy D., McKee M., Stuckler D. Financing universal health coverage--effects of alternative tax structures on public health systems: cross-national modelling in 89 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015;386(9990):274–280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwerdtle P., Morphet J., Hall H. A scoping review of mentorship of health personnel to improve the quality of health care in low and middle-income countries. Glob Health. 2017;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0301-1. 77-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Champion V.L., Skinner C.S. The health belief model. Health Behav Health Educ: Theory Res Pract. 2008;4:45–65. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutayeb A. The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in developing countries. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall V., Thomsen R.W., Henriksen O., Lohse N. Diabetes in Sub Saharan Africa 1999-2011: epidemiology and public health implications. A systematic review. BMC Publ Health. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-564. 564-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald H.I., Thomas S.L., Nitsch D. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for acute community-acquired infections in high-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004100. e004100-e004100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tasaka S., Tokuda H. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in non-HIV-infected patients in the era of novel immunosuppressive therapies. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18(6):793–806. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Southwick S.M., Charney D.S. Responses to trauma: normal reactions or pathological symptoms. Psychiatr Interpers Biol Process. 2004;67(2):170–173. doi: 10.1521/psyc.67.2.170.35960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariotti A. The effects of chronic stress on health: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain-body communication. Future Sci OA. 2015;1(3) doi: 10.4155/fso.15.21. FSO23-FSO23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCook A. COVID-19: stockpiling refills may strain the system. 2020. https://www.idse.net/Policy--Public-Health/Article/03-20/COVID-19-Stockpiling-Refills-May-Strain-the-System/57583 March 11; Special.

- 18.Viswanathan M., Golin C.E., Jones C.D. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785–795. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-11-201212040-00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y., Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 epidemic in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. 2020:20025395. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. 2020.2002.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanghøj S., Boisen K.A. Self-reported barriers to medication adherence among chronically ill adolescents: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(2):121–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kretchy I.A., Owusu-Daaku F.T., Danquah S.A. Mental health in hypertension: assessing symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress on anti-hypertensive medication adherence. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8 doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-25. 25-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakata A. Psychosocial job stress and immunity: a systematic review. In: Yan Q., editor. Psychoneuroimmunology: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2012. pp. 39–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salleh M.R. Life event, stress and illness. Malays J Med Sci : MJMS. 2008;15(4):9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viswanathan M., Kahwati L.C., Golin C.E. Medication therapy management interventions in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):76–87. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan R., Santesso N., Lowe D. Interventions to improve safe and effective medicines use by consumers: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007768.pub3. CD007768-CD007768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammed M.A., Moles R.J., Chen T.F. Impact of pharmaceutical care interventions on health-related quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(10):862–881. doi: 10.1177/1060028016656016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hepler C., Strand L. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.George P., Molina J., Cheah J., Chan S., Lim B. The evolving role of the community pharmacist in chronic disease management - a literature review. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson C., Bates I., Beck D. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce: enabling concerted and collective global action. Am J Pharmaceut Educ. 2008;72(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7206127. 127-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mossialos E.C.E., Naci H., Benrimoj S. “retailers” to health care providers: transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Pol. 2015;119:628–639. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al Aqeel S., Abanmy N., AlShaya H., Almeshari A. Interventions for improving pharmacist-led patient counselling in the community setting: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0727-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snopkova M., Szmicsekova K., Sukel O. Polypharmacy and interactions - what is A pharmacist role? Value Health. 2017;20(9):A510. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kousar R., Murtaza G., Azhar S., Khan S.A., Curley L. Randomized controlled trials covering pharmaceutical care and medicines management: a systematic review of literature. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14(6):521–539. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilby K.J., Lacey J. Pharmacist-led medication-related needs assessment in rural Ghana. SpringerPlus. 2013;2(1) doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-163. 163-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kripalani S., Yao X., Haynes R.B. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(6):540–549. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva R.D.M.L., dos Santos G.A. Pharmacist-participated medication review in different practice settings: service or intervention? An overview of systematic reviews. PloS One. 2019;14(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pharmacists are on the front line of COVID-19, but they need help too. Pharmaceut J. March 2020;(7935):304. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sørensen Janina Maria. Herb–drug, food–drug, nutrient–drug, and drug–drug interactions: mechanisms involved and their medical implications. J Alternative Compl Med. 2002;8(3):293–308. doi: 10.1089/10755530260127989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Wijk B.L.G., Klungel O.H., Heerdink E.R., de Boer A. Effectiveness of interventions by community pharmacists to improve patient Adherence to chronic medication: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(2):319–328. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Granger B.B., Bosworth H.B. Medication adherence: emerging use of technology. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26(4):279–287. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328347c150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.