Ousmane Faye and colleagues1 recently described the chains of transmission for 152 individuals infected with Ebola virus diseases in Guinea. The resulting transmission trees provide unique insights into the individual variation in the number of secondary cases generated by an infected index case. A better understanding of this variation provides crucial information about epidemic spread, the expected number of superspreading events, and the effects of control measures.2

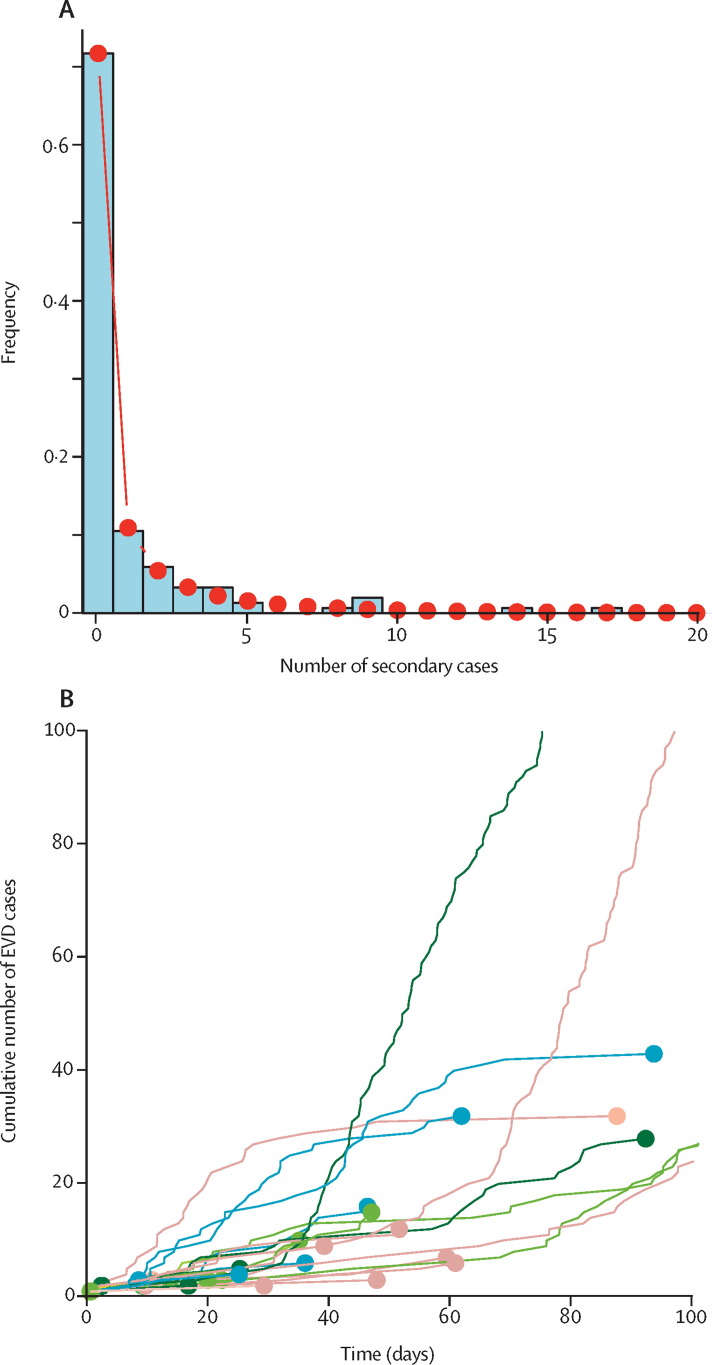

The number of secondary cases in the transmission trees is highly skewed, with 72% of individuals not generating further cases (figure ). Fitting a negative binomial distribution to the data (appendix) provides maximum-likelihood estimates of the mean (0·95, 95% CI 0·57–1·34) and the dispersion parameter (k=0·18, 95% CI 0·10–0·26). The mean corresponds to the basic reproduction number (R 0) of the overall population. The estimated value of k, which is substantially smaller than 1, suggests that the distribution of the individual reproduction number is highly overdispersed.2 The value for Ebola virus disease is similar to that estimated for severe acute respiratory syndrome (k=0·16).2 This finding suggests that superspreading events for Ebola virus disease are an expected feature of the individual variation in infectiousness.3

Figure.

Distribution of the number of secondary cases and outbreak trajectories for Ebola virus disease

(A) The histogram represents the observed frequencies in the number of secondary cases as given by the transmission trees in Faye and colleagues' study.1 The line and dots correspond to the fitted negative binomial distribution. (B) Each line represents one of 200 stochastic realisations of epidemic trajectories. Dots show when the outbreak becomes extinct. A detailed analysis is reported in the appendix. EVD=Ebola virus disease.

I simulated stochastic trajectories of Ebola virus disease outbreaks starting from one infected index case (figure). To this end, I drew the number of secondary cases for each case from the fitted negative binomial distribution (appendix). The time from disease onset in one case to disease onset in the next case was drawn from the reported gamma-distributed serial interval with a mean duration of 15·3 days.4 Although most outbreaks rapidly become extinct, some epidemic trajectories can reach to more than 100 infected cases. This finding is particularly remarkable because R 0 is less than 1, and shows the potential for explosive outbreaks of Ebola virus disease.

R 0 during the early phase of the Ebola virus disease epidemic in Guinea has been estimated to be roughly 1·5.5 The transmission trees from Faye and colleagues were generated from data obtained between February and August, 2014, when the reproduction number was fluctuating around unity.1, 4 That scenario is similar to the present situation in parts of west Africa where the incidence is declining but new outbreaks still occur. The observed variation in individual infectiousness for Ebola virus disease means that although the probability of extinction is high, new index cases also have the potential for explosive regrowth of the epidemic.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com/infection on May 19, 2015

Acknowledgments

I received funding through an Ambizione grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (project 136737). I declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Faye O, Boëlle P-Y, Heleze E. Chains of transmission and control of Ebola virus disease in Conakry, Guinea, in 2014: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:320–326. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71075-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp ME, Getz WM. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Science. 2005;438:355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature04153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volz EM, Pond SL. Phylodynamic analysis of Ebola virus in the 2014 Sierra Leone epidemic. PLoS Curr. 2014 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.6f7025f1271821d4c815385b08f5f80e. published online Oct 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Ebola Response Team Ebola virus disease in West Africa—the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl J Med. 2014;317:1481–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Althaus CL. Estimating the reproduction number of Ebola virus (EBOV) during the 2014 outbreak in West Africa. PLoS Curr. 2014 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.91afb5e0f279e7f29e7056095255b288. published online Sept 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.