Abstract

Gas-filled ultrasound (US) contrast agents easily collapse in the body, and the gas can easily overflow, which limits the effectiveness of US imaging. To address this issue, an injectable gas-generating multi-mode system was developed that carries the MR negative contrast agent Fe3O4, the fluorescent dye Cy5.5, and the CO2 releasing donor (Na2CO3). The nanoparticles can continuously generate carbon dioxide (CO2) gas in acidic tumour tissue in the body, giving the tumour a strong echo signal under ultrasonic imaging. In addition, the nanoparticles confer excellent effects for MR and fluorescence imaging of the tumour tissue. The results indicate that this pH-responsive NP system provides good effects in MR/US/fluorescent imaging. This study provides a useful reference for multi-mode tumour imaging.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Gas-generating nanoparticle, Multi-mode imaging, Tumour targeting, Contrast agent

Introduction

In clinical practice, microbubbles are primarily applied as ultrasound contrast agents for the real-time imaging of various organs and blood vessels [1–3]. Traditional ultrasound contrast agents typically consist of materials such as lipids or proteins that enclose air or perfluorocarbon gases. The gas species encapsulated in the microspheres have low stability in the blood and a short half-life because of the rapid diffusion of microbubble defects [4–6]. Moreover, because the particle size of the gas-filled microbubbles is usually large (approximately 1 to 8 μm), it is difficult for the microbubbles to penetrate into the host tumour environment by tissue extravasation. Therefore, the current application of micron-sized bubbles in intravascular imaging is limited [7]. Ideal ultrasound contrast agents should generally exhibit an optimal size for transport through the tissue vascular space, an adequate duration of acoustic effect, good targeting and biocompatibility, and easy excretion from the body [8, 9]. The concept of “gas-generating nanoparticles” was proposed in prior research, and such nanoparticles have the potential for use in ultrasound contrast imaging [10–12]. These gas-generating nanoparticles are superior to the current gas-filled microbubbles in performance, and the continuously generated gas enables intense ultrasound imaging. Gas-generating nanoparticles can enhance permeation and retention, and they may stably circulate in the blood and effectively accumulate in the tumour tissue [13, 14].

It remains a challenge to detect tiny and occult tumours by traditional imaging methods, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and ultrasound, which are limited by long acquisition times, high radiation dose, and poor sensitivity [15, 16]. It is necessary to integrate different imaging methods and develop multi-modal imaging technology to achieve integrate synergy for the early detection of cancer [17–19]. Superparamagnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles can be used as negative MRI contrast agents in T2-weighted imaging [20, 21]. Fe3O4 has attractive overall properties, including small particle size, strong penetrability, high magnetization, good metabolism, and relatively low toxicity [22, 23]. Fe3O4 contrast agents for the MRI diagnosis of early-stage cancer have been extensively studied due to their high relaxation and contrast [24–26]. In addition, real-time fluorescence imaging has excellent resolution and can be a valuable method for defining tumour staging, guiding tumour resection, and monitoring the treatment effects [27, 28].

Herein, these nanoparticles are mainly encapsulated by poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA), which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as a biosafe material [29, 30]. The PLGA particles are modified with RGD peptide to enable binding to αvβ3 integrin on the surface of breast cancer cells and with Cy5.5 as a fluorescent dye for imaging in vivo, and they are encapsulated with Fe3O4 to act as a T2-negative contrast agent in MRI (Scheme 1a). Due to the upregulated glycolysis in tumour tissue, which could produce more lactic acid and protons in the extracellular environment, the pH of tumour tissues (6.8–7.2) is lower than that of normal tissues (pH 7.4) [31–33]. Thus, we designed sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) in the PLGA to produce CO2 bubbles at the lower pH of tumour tissues for ultrasound imaging. To verify their promising application in tumour imaging, the comprehensive properties of these multi-mode nanoparticles for in vitro imaging were systematically characterized, including their cytotoxicity, targeting specificity, and biodistribution in tumour tissue, by three imaging modes.

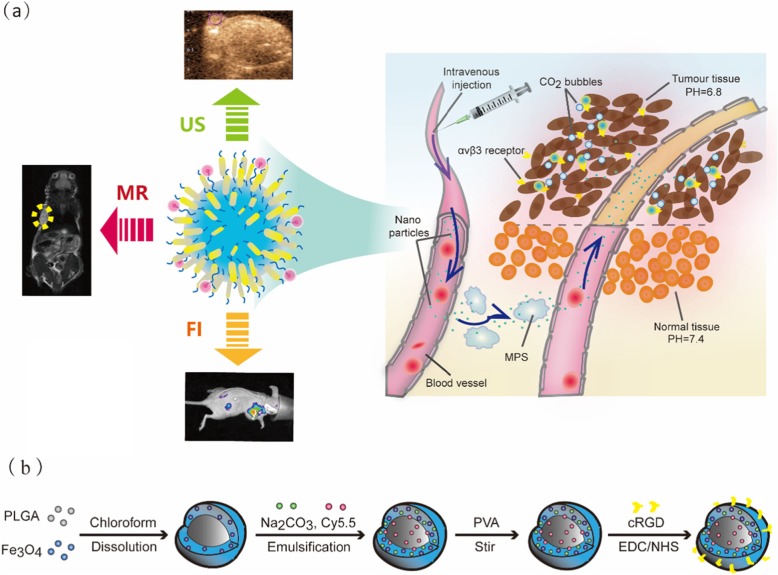

Scheme 1.

a Schematic diagrams of the function in Fe3O4/Na2CO3 @PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs via targeted accumulation into the tumor and generating CO2 bubbles in acid tumor tissues, followed by triple-modal MR/US/FI imaging of breast cancer. b Schematic illustration of the preparation of the Fe3O4/ Na2CO3 @PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of Na2CO3/Fe3O4 @PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs

Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs were designed as RGD-targeted multi-mode contrast agents by encapsulating a biocompatible polymer of PLGA with Fe3O4 and Na2CO3 and an integrin-targeted agent via a biodegradable chemical bond (Scheme 1b).

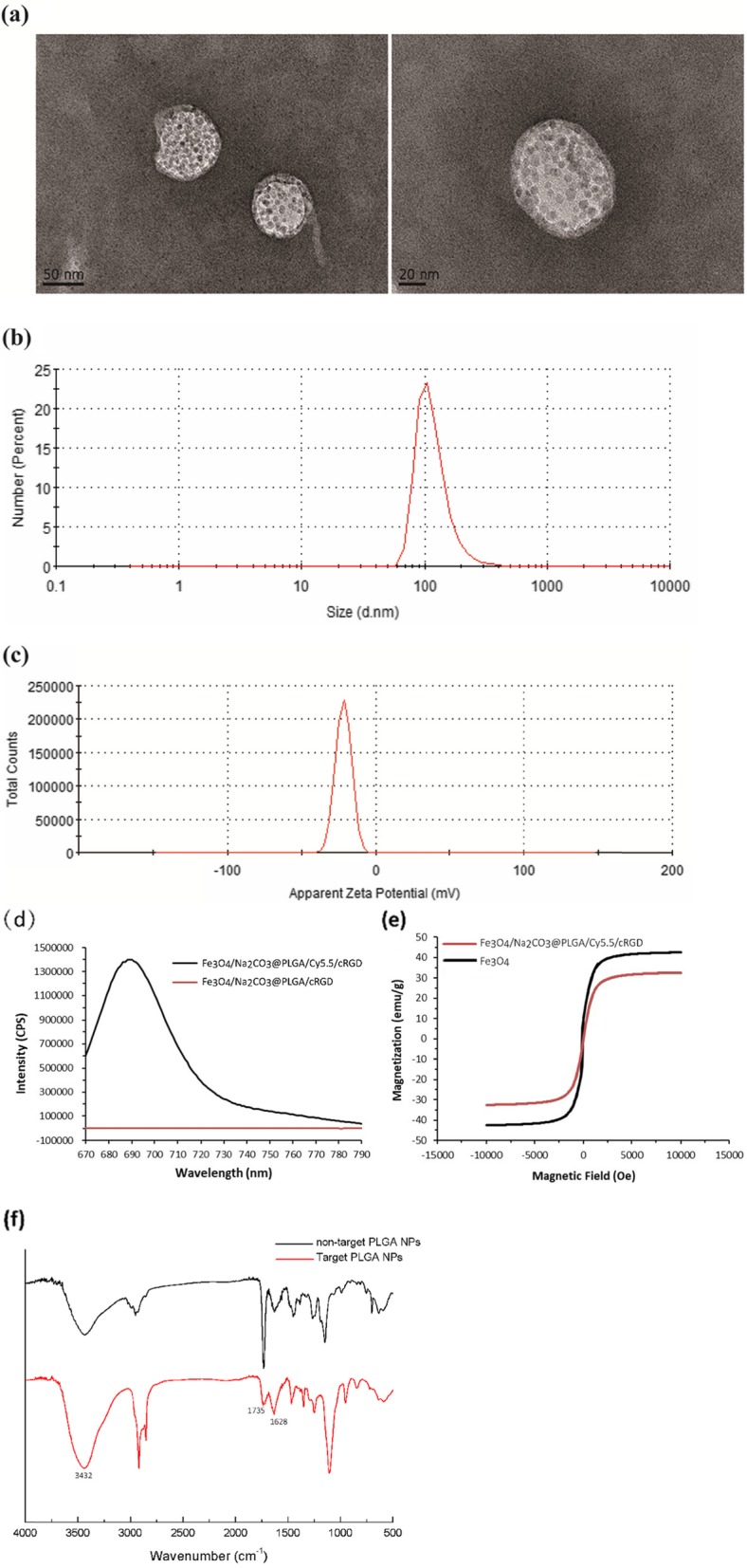

Transmission electron microscopy images showed that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs were clear spheres with uniformly dispersed iron oxide particles visible in the shell (Fig. 1a). The average hydrodynamic size of the NPs was measured as 117.6 nm by dynamic light scattering, and the average polydispersity index was 0.234 (Fig. 1b). The surface charge of the NPs was confirmed by zeta potential measurements to be − 21.7 mV (Fig. 1c). Fluorescence spectrum measurement revealed that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD had the maximum emission wavelength at 685 nm, indicating that Cy5.5 was successfully encapsulated in the PLGA core (Fig. 1d). The saturation magnetization values for Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD and free Fe3O4 NPs were equal to 32.6 and 42.5 emu/g, respectively (Fig. 1e). These findings indicated the superparamagnetic characteristic of the nanoparticles at room temperature. The FITR spectrum of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD showed that N-H stretching vibration and –OH absorption peak appeared around 3432 cm−1. In addition, we found an enhancement (1628 cm−1) of the C = O stretching vibration. Compared to that of the non-targeted NPs, the characteristic peak (the carboxyl) at 1735 cm−1 of the targeted NPs was significantly reduced. The results showed the bonding between the carboxyl group on the microsphere surface and the amino group on RGD peptide. In vitro binding of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs is shown in Fig. 1f.

Fig. 1.

TEM images (a) Size distributions (b) Zeta potential (c) of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs. d Fluorescence emission spectrum of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD and Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/cRGD NPs. e Magnetic hysteresis curves of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs and Fe3O4 NPs. f The FTIR of spectra of targeted Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD and non-targeted PLGA NPs

In vitro binding of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs

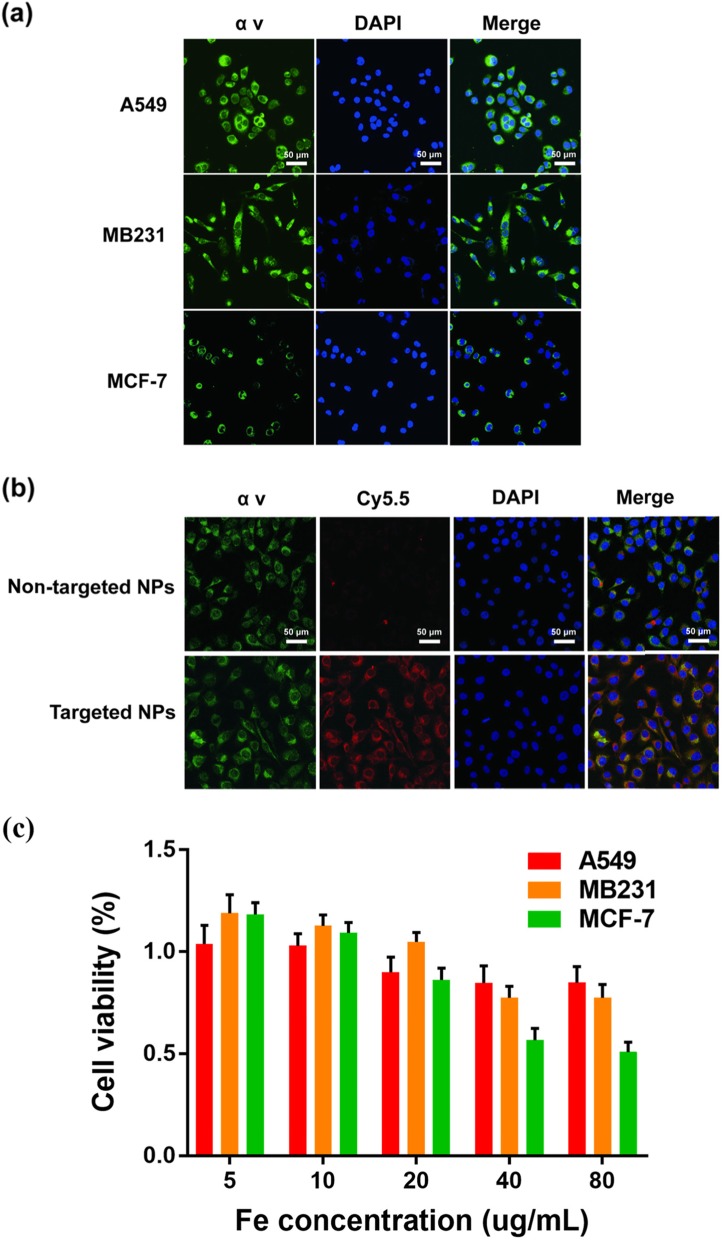

αvβ3 integrin is generally highly expressed on breast cancer tumour endothelial cells and can promote tumour metastasis [33–36]. Cellular immunofluorescence for the expression of αv integrin in MDA-MB-231 cells was much higher than that in MCF-7 cells; A549 cells served as positive controls (Fig. 2a). The cellular uptake of NPs was studied by CLSM (Fig. 2b). The Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs showed a much higher binding rate to MD-MB-231 cells than did non-targeted NPs. The fluorescence images also revealed that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs bound to the cell cytoplasm, and merged images showed the same locations as the expression of αv integrin [37, 38].

Fig. 2.

a Confocal fluorescence images with the expression of αv integrin on MB231, A549, and Mcf-7 cells. Blue and green represent DAPI and αv fluorescence, respectively. b Confocal fluorescence images of MB231 cells incubated with targeted Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs and non-targeted NPs. Blue, red, and green, represent DAPI, Cy5.5, and α v fluorescence, respectively. c Relative viability of MB231 cells incubated with different concentrations of Fe3O4/Na2CO3 @PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs

Cytotoxicity assay

The in vitro cytotoxicity of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs was estimated in MDA-MB-231 cells using a CCK8 assay, while A549 and MCF-7 cells treated with NPs were used as controls (Fig. 2c). In the range of Fe concentrations of 5–80 μg/mL, the cell viability of A549 and MB231 cells was not significantly reduced, and both were above 70%. In contrast, MCF-7 cells showed a significant decrease in cell viability to approximately 50% at Fe concentrations higher than 40 μg/mL. The CCK8 results demonstrated that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs showed significantly lower cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 cells over a given concentration range.

In vitro contrast imaging

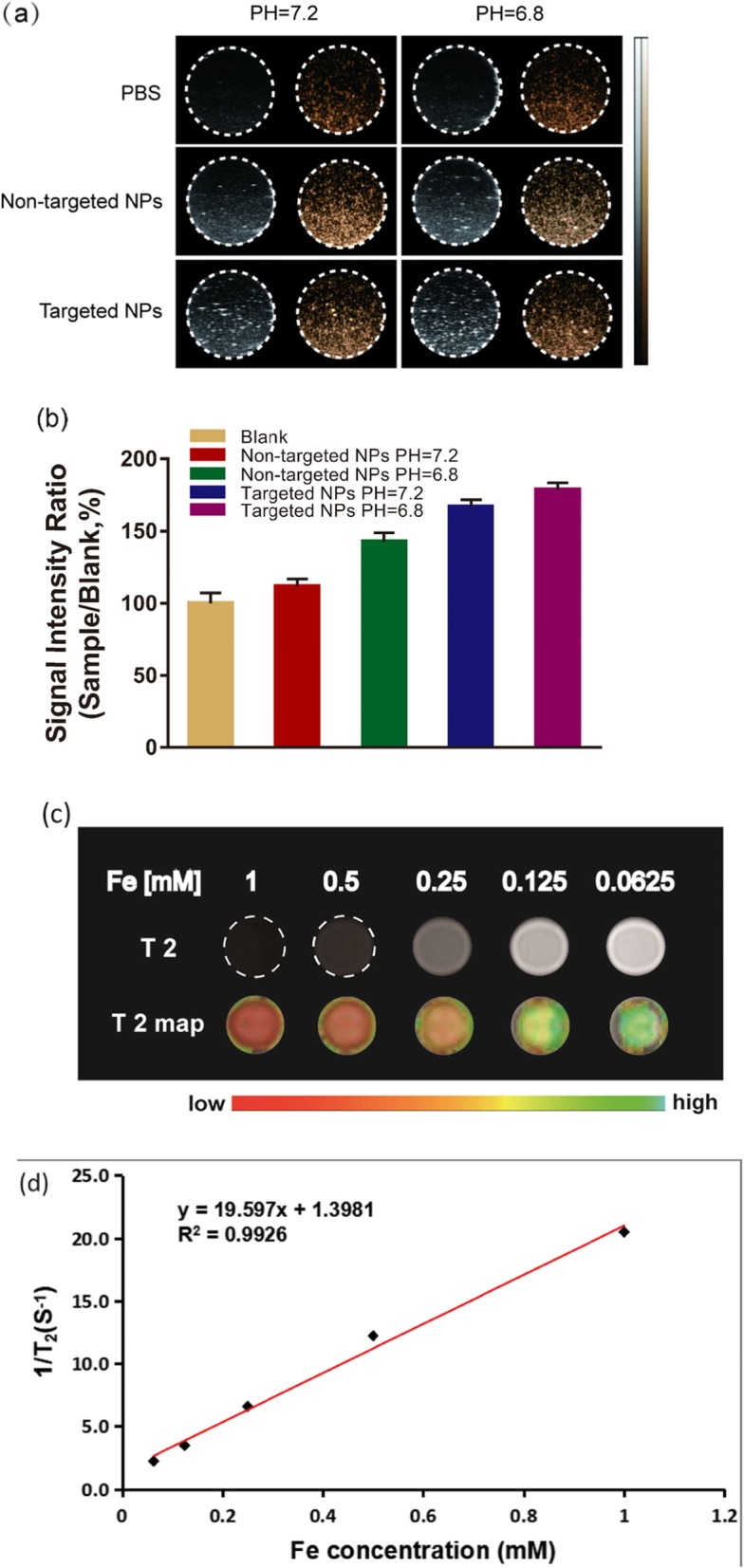

We used an agar gel phantom to study the performance of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs in vitro at different pH values (Fig. 3a). The ultrasound contrast images of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs were significantly enhanced at weakly acidic pH (pH 6.8) compared with pH 7.2, likely because pH 7.2 does not produce enough CO2 bubbles for ultrasound imaging. In contrast, when the NPs were in a weakly acidic environment, enough bubbles could be generated for ultrasound imaging. This characteristic is relevant to tumours, which exhibit high tissue heterogeneity and diverse pH levels (pH 6.8–7.2) in vivo [32, 39, 40]. The signal intensity of the ultrasound image was then analyzed (Fig. 3b). The signal intensity ratios of the non-targeted NP (pH = 7), non-targeted NP (PH = 5), targeted NP (PH = 7), and targeted NP (PH = 5) groups relative to the signal intensity of the blank group were 112%, 145%, 167%, and 178 ± 4%, respectively, which clearly indicates that the targeted NP group (PH = 5) had the strongest US signal.

Fig. 3.

a Ultrasonic images of the targeted NPs and non-targeted NPs recorded at different pH values (7.2 and 6.8), PBS as a control. b Signal intensity rate is calculated by sample/blank, sample represents the echo intensity of the targeted and non-targeted NPs, and blank represents the echo intensity of PBS. c T2-weighted MR images of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs with different Fe concentrations (0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mM). d The transverse relativities (r2) were 19.597 mM−1 s−1 for Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs

For the MRI study in vitro, as the concentration of Fe in the Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs increased, the T2-weighted signal intensity showed a significant decrease, indicating the possibility of these NPs for use as T2 MR contrast agents (Fig. 3c). The transverse relaxation rate (r2) of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs was calculated to be 19.597 mM−1 s−1. Although the transverse relaxation rate (r2) of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs is lower than that of many other MRI superparamagnetic agents, the composition of Fe3O4 can increase the r2, which was 2.94 times higher than the r2 of SPIO particles used clinically.

Ultrasound contrast imaging of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs

To demonstrate the potential of the Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs for ultrasound imaging in tumours, we administered a tail vein injection of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs to breast cancer xenograft nude mice and monitored the ultrasound images as a function of time (Fig. 4a). Before injection, images of the tumour, liver, and subcutaneous area were recorded. Immediately after injection, the area of the tumour tissues did not show any contrast enhancement. Enhancement of the tumour area was observed beginning 30 min after injection and lasted for 90 min. The in vivo ultrasound results showed that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/ RGD NPs generated enough bubbles in acidic tumour tissues to produce echogenic reflectivity for ultrasound imaging. As a control, we also obtained images of the liver and subcutaneous tissues at different times after injection of the targeted NPs. Throughout the observation period, no significant enhancement was found in the subcutaneous injection area, and the enhancement in the liver, which decreased over time, was significantly lower than that in the tumours (Fig. 4b). This result indicates that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs circulating in the body at physiological pH do not produce a substantial amount of CO2 bubbles for ultrasound contrast enhancement.

Fig. 4.

a In vivo ultrasound imaging of tumors, livers, and subcutaneous areas at different time after injection of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs. b Echo intensity rate as a function of time is calculated by tissue/blank, tissue represents the echo intensity of the tumor, liver, or subcutaneous area, blank represents the echo intensity before injection

MRI of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs

For in vivo MRI, to demonstrate that NPs can be used for tumour-specific imaging, Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs were injected directly into tumours and muscles. The results showed that the tumour area exhibited a significant decrease in T2-MR contrast after injection of the targeted NPs, and the signal intensity decreased significantly from 8875 at 0 min to 5972 at 120 min after injection (Fig. 5a, b). However, with the same amount of nanoparticles injected, the subcutaneous muscle area showed a much lower T2 signal decrease. This finding demonstrates the effectiveness of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs with hypersensitive integrin-targeted T2-MR contrast agents for use in tumour-targeted imaging. In the tail vein injection group, T2-MR imaging also showed an obvious decrease in contrast in the tumour at 24 h post-injection, demonstrating the high tumour accumulation of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs (Fig. 5c, d). Moreover, decreased T2 signals were observed in the liver and kidneys, indicating that the iron ions in the NPs could be rapidly cleared from the body. Therefore, MRI revealed that the PLGA-wrapped Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibited efficient passive tumour targeting via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, especially RGD-mediated targeting, but could be decomposed and quickly excreted in vivo.

Fig. 5.

a In vivo T2-MR images of normal and tumor subcutaneous tissues before and after injection of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs. b Average signal intensity in muscle and tumor for injection of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs. c T2-MR images on axial and coronal of MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice before and after intravenous injection of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs. d Signal intensity ratio is calculated by tissue/muscle, tissue stands for the signal intensity of the tumor, liver, and kidney before and after injection of the targeted NPs, muscle stands for the signal intensity of the muscle at the same time

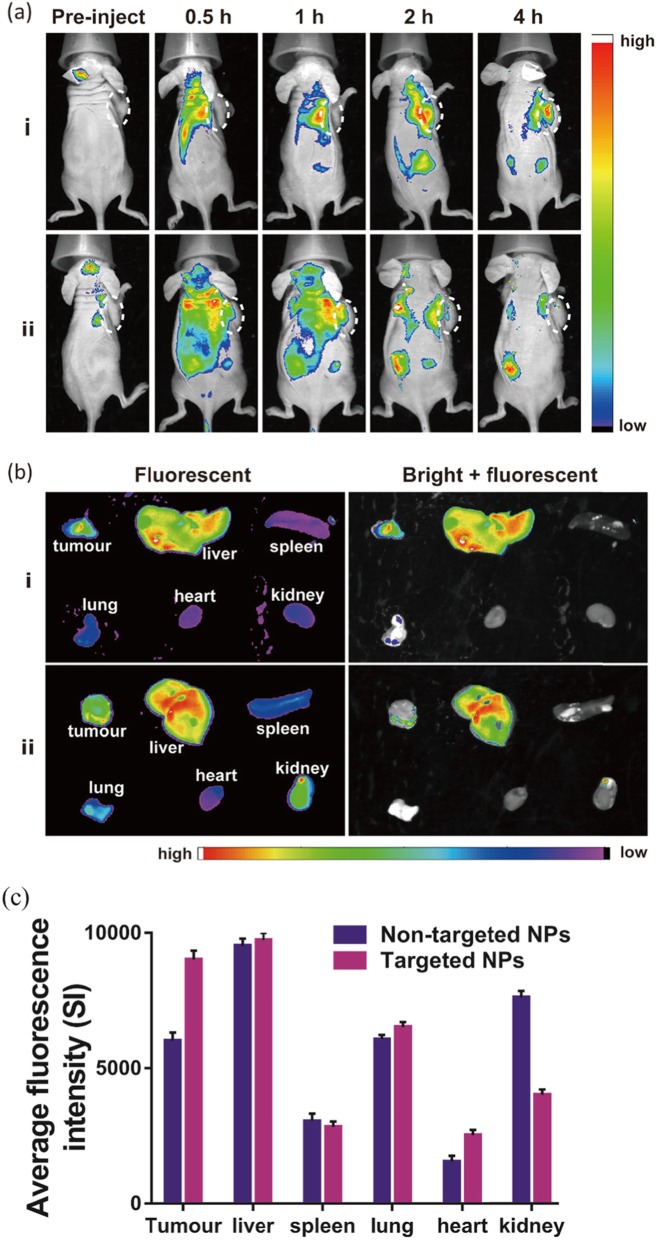

Fluorescence imaging and histology

Two hundred microliters of NPs were intravenously injected into mice for in vivo fluorescence imaging. In the group injected with RGD-targeted NPs, the fluorescence signal of Cy5.5 gradually increased in the tumour area and reached a peak at 4 h after injection, indicating that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs can effectively accumulate in the tumour. In the non-targeted group, NPs were distributed throughout the body after injection and rapidly cleared, and they did not accumulate in the tumour for a long period of time (Fig. 6a). The mice were then dissected, and the main organs and tumours were collected for in vitro fluorescence imaging, which revealed high tumour uptake of the targeted NPs (Fig. 6b, c). The fluorescence intensity of Cy5.5 in the tumours of mice injected with targeted NPs was 1.5 times that in mice injected with non-targeted NPs.

Fig. 6.

a In vivo fluorescence fluorescence imaging of animals at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h post-injection after injection of targeted and non-targeted NPs. b Ex vivo fluorescence images of tumors and major organs (liver, spleen, lung, heart, and kidney) collected from animals. c Averaged fluorescence intensity of various organs and tumors

Furthermore, tumour-specific targeting of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs was verified by tissue fluorescence imaging of frozen tumour sections (Fig. 7a). Immunofluorescence staining of tumour sections with antibodies against αv and β3 integrin revealed significant expression of αvβ3 integrin in tumour tissues. The fluorescence of αv and β3 integrin was merged with the Cy5.5 fluorescence of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs to obtain an immunostaining image revealing colocalization. The immunofluorescence results in the tumour tissues indicated that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs specifically bind to αvβ3 integrin in MB231 malignant breast cancer. Moreover, H&E staining of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs compared with the non-targeted group showed that all organ tissue sections had normal pathological morphology and no histopathological damage response (Fig. 7b). All the results of the above cytotoxicity and histological analysis indicated that Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs induced no significant toxicity to major organ tissues in vivo, and their good biocompatibility can be reasonably attributed to PLGA.

Fig. 7.

a Fluorescent imaging of MDA-MB-231 tumor frozen sections from mice injected with targeted and non-targeted NPs. Green, red, purple, and blue represent αv, β3, Cy5.5, and DAPI fluorescence, respectively. b H&E-stained tumor slices collected from mice after injection of targeted and non-targeted NPs

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results above demonstrate a creative and successful approach for MRI of breast cancer through a magnetic targeting and a gas-generating system that is activated in the tumour microenvironment. Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs exhibit excellent imaging performance and good biocompatibility in MR/ultrasound/fluorescent imaging modes. Our work shows the strong potential for tumour diagnosis with improved multi-modal imaging.

Materials and methods

Materials

Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) (lactide:glycolide = 75:25, Mw = 20,000), Cyanine5.5 dye, and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company (Shanghai, China). The RGD peptide was custom synthesized by GenicBio BioTech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Fe3O4 nanoparticles and sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) were purchased from Xian Ruixi Biological Technology Co. Ltd. (Henan, China). Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Solarbio Company (Beijing, China). All chemicals were of analytical grade.

Synthesis of Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD nanoparticles

First, 12.5 mg of PLGA and 0.25 mL of chloroform were mixed together. Then, 5 μL of Cy5.5, 15 μL of oleic acid-modified magnetic nanoparticles dispersed in chloroform (OA@Fe3O4, 10 mg/mL), 5 μL of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), and 1.5 mL of 1% PVA solution were added in sequence and emulsified with an ultrasonic processor for 2 min. Then, 12.5 mL of 0.3% PVA solution was added and stirred for 3–4 h at room temperature, and 12.5 mL of 0.4% PVA solution was added for stirring (500 rpm/min) overnight to remove residual organic solvent. The above solution was subjected to several ultrafiltration washings with ddH2O and then diluted with PB buffer (pH = 7.4) to a final volume of 1.25 mL. Next, 0.25 mg of EDC and 1.25 mg of NHS were added to the above mixed solution. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at 25 °C and then, washed three times with ultrafiltration and resuspended in PB buffer solution (pH = 7.4). Next, 1.25 mg of cRGD was added to the solution and stirred at 4 °C overnight. To remove EDC, NHS, and any residual cRGD, the transparent solution was filtered by an ultrafiltration tube. Finally, Fe3O4/Na2CO3@PLGA/Cy5.5/cRGD NPs were resuspended in 1.25 mL of deionized water and stored at 4 °C.

Nanoparticle characterization

The dynamic diameters and zeta potential of nanoparticles were measured by a Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK). The morphology of the nanoparticles was obtained using a FEI Tecnai F20 transmission electron microscope. The Cy5.5 loading was recorded by a Hitachi F-7000 fluorescence spectrometer. FTIR was performed using a fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Alpha II, Bruker, Switzerland). A vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, Lake Shore 7410) was applied to determine the hysteresis curve of the nanoparticles and free Fe3O4.

Cells and animals

Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells were kindly provided by the Stem Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in 95% air and 5% CO2. Female BALB/c mice (4 weeks) were purchased from Shanghai Slaccas Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. and maintained according to protocols approved by the Guangxi Medical University Laboratory Animal Center. Animal experiments were followed with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, released by the Animals Ethics Committee of Laboratory Animal Center, Guangxi Medical University. MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were transplanted into the right flank of BALB/c mice (2 × 106 in 200 μl cells per mouse) and allowed to grow for 10–14 days (mean diameter 5 mm) before imaging.

Cellular expression of αv integrin

Cellular immunofluorescence was carried out to confirm the high expression of αv integrin in MDA-MB-231 cells. A549 and MCF-7 cells were used as controls. Cells were seeded onto 35 mm glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek, USA) at 2 × 104 cells mL−1 for 24 h. After incubation, cells were fixed for 20 min at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde. Then, they were incubated with rabbit monoclonal anti-integrin αv antibody (ab179475, Abcam) at 4 °C overnight and anti-rabbit IgG antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the cells were stained with DAPI. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy (TCS SP8, Leica, Germany).

To assess the targeting efficacy of the nanoparticles, a cellular uptake study was performed by using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Cells were seeded onto 35 mm glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek, USA) at 2 × 104 cells mL−1 for 24 h. Then, the cells were incubated with RGD-targeted NPs (30 μg mL−1, 0.5 mL) at pH 7.4 for 2 h, and non-targeted NPs were used as controls. After incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and then incubated with αv antibody. By means of colocalization, we verified the targeted binding of the nanoparticles to the integrin on the cells.

CCK8 assay

The biocompatibility of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD nanoparticles was evaluated by a cytotoxicity study. MDA-MB-231, A549, and MCF-7 cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells mL−1 for 24 h. Then, 0.1 mL of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NP suspension at Fe concentrations of 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μg/mL was added to each well and incubated for 24 h. Finally, 10 μL of CCK8 solution was added, and the suspension was incubated for another 1 h. The results were determined by a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 450 nm.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging

Ultrasound imaging of nanoparticles was performed by using a Vevo 2100 (Fujifilm Visual Sonics Inc., Canada) ultrasound system. The RGD-targeted and non-targeted NPs were added to the agarose model, and PBS was used as a control. Images were recorded in B-mode and CEUS-mode with different pH buffers of 7.2 and 6.8. The area of interest was drawn, and the average grey value was measured in B-mode images.

For in vivo ultrasound imaging, mice were anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Hebei Yipin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China), and body temperature was maintained at 37 °C with a heated pad. A total of 200 μL of RGD-targeted NPs was injected via the tail vein. Control animals received a subcutaneous injection with the same amount of NPs. Ultrasonic images were recorded using a 7-MHz transducer to continuously acquire ultrasound images of the tumours, livers, and subcutaneous areas. The acoustic focus zone was placed at the centre of the tumour with the largest cross-section, and a field of view containing the tumour and its adjacent tissue was obtained.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI exams of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs were performed using a 3.0 T MR (GE Healthcare, USA) and an animal coil (RF TECH LIMITED, China). NPs with different Fe concentrations of 0.031, 0.063, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mM were scanned in 1 mL Eppendorf tubes, and PBS was used as a control. T2 MRI was performed for each tube using a T2-weighted FSE sequence (slice thickness of 3 mm, TR/TE 2000/74.4 ms, 8 × 8 cm FOV, and 320 × 256 matrix). The relaxivities (r2) were calculated by a linear fitting of the inverse relaxation time as a function of the Fe concentration.

For in vivo MRI, mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 3) for MR scanning that received either (1) local injection of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs within subcutaneous muscle and tumour tissues or (2) tail vein injection of Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/Cy5.5/RGD NPs. Baseline images of the mice were taken before injection of the nanoparticles. For group one, the same amount of NPs was injected into the subcutaneous and tumour tissues, and MRI scanning was performed every 30 min to record the signal transition of the tissues. For group two, tumour imaging was performed in the axial and coronal positions, and the MR parameters were the same as those used for in vitro imaging. The signal intensity (SI) in the region of interest (ROI) was measured and compared to tissue signals at different times before and after injection.

Tumour fluorescence imaging

For fluorescence imaging in vivo, an in vivo fluorescence imaging system (FX PRO, Bruker, Switzerland) was used for scanning, and the mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 3): (1) RGD-targeted NPs and (2) non-targeted NPs. Images were captured every 30 min for a period of 4 h after the injection. Subsequently, important organs and tumours were harvested and imaged, and the distribution of fluorescence in the organs of the body was observed. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity was performed using molecular imaging software (Bruker, Switzerland). These important organs then underwent H&E staining to evaluate the tissue toxicity. Frozen tumour sections were also subjected to fluorescence immunostaining with antibodies against αv integrin and β3 integrin.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Cy5.5

Sulfo-Cyanine5.5 NHS ester

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EDC

1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride

- FSE

Fast spin echo

- MR

Magnetic resonance

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- PB

Phosphate buffer

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- PVA

Polyvinyl alcohol

- RGD

Arginine–glycine–aspartate

- TE

Echo time

- TR

Repetition time

Authors’ contributions

ZN, NL, and DS designed the experiments. ZN and ZX performed the experiments. JL, XZ, and YZ analyzed the data. ZN, NL, and YZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81760517).

Availability of data and materials

The conclusions made in this manuscript are based on the data which are all presented and shown in this paper.

Competing interests

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhenhui Nie and Ningbin Luo contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhenhui Nie, Email: niezhenhui@hotmail.com.

Ningbin Luo, Email: luoningbin@hotmail.com.

Junjie Liu, Email: liujunjie1979@hotmail.com.

Xinyi Zeng, Email: zengxinyia@hotmail.com.

Yu Zhang, Email: zhangyuzzyy@hotmail.com.

Danke Su, Email: sudanke@gxmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Jai Il P, Dinesh J, Ross W, et al. Microbubbles loaded with nanoparticles: a route to multiple imaging modalities. Acs Nano. 2010;4(11):6579–6586. doi: 10.1021/nn102248g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fabian K, Stanley F, Patrick K, Wiltrud L, Twan L. Ultrasound microbubbles for molecular diagnosis, therapy, and theranostics. J Nuclear Med. 2012;53(3):345–348. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mcewan C, Owen J, Stride E, et al. Oxygen carrying microbubbles for enhanced sonodynamic therapy of hypoxic tumours. J Controlled Release. 2015;203(3):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Min HS, Kang E, Koo H, et al. Gas-generating polymeric microspheres for long-term and continuous in vivo ultrasound imaging. Biomaterials. 2012;33(3):936–944. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloch SH, Wan M, Dayton PA, Ferrara KW. Optical observation of lipid- and polymer-shelled ultrasound microbubble contrast agents. Appl Physics Letters. 2004;84(4):631–633. doi: 10.1063/1.1643544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otani K, Nishimura H, Kamiya A, Harada-Shiba M. Simplified preparation of α v β 3 integrin-targeted microbubbles based on a clinically available ultrasound contrast agent: validation in a tumor-bearing mouse model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018;44(5):S0301562918300413. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson SR, Burns PN. Microbubble-enhanced US in body imaging: what role? Radiology. 2010;257(1):24–39. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Cai W, Xu L et al (2015) Nanobubble–Affibody: novel ultrasound contrast agents for targeted molecular ultrasound imaging of tumor. Biomaterials. 37:279–288 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Li Y, An H, Wang X, et al. Ultrasound-triggered release of sinoporphyrin sodium from liposome-microbubble complexes and its enhanced sonodynamic toxicity in breast cancer. Nano Research. 2018;11(2):1038–1056. doi: 10.1007/s12274-017-1719-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu L, Hu P, Chen Y. (2018) Gas-Generating Nanoplatforms: Material Chemistry, Multifunctionality, and Gas Therapy. Adv Materials. 30(49):e1801964 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kun Z, Huixiong X, Hangrong C et al (2015) CO2 bubbling-based ‘nanobomb’ system for targetedly suppressing Panc-1 pancreatic Tumor via low intensity ultrasound-activated inertial cavitation. Theranostics. 5(11):1291–1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kyung Hyun M, Hyun Su M, Jae LH, et al. pH-controlled gas-generating mineralized nanoparticles: a theranostic agent for ultrasound imaging and therapy of cancers. Acs Nano. 2015;9(1):134–145. doi: 10.1021/nn506210a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min HS, Son S, Dong GY, et al. Chemical gas-generating nanoparticles for tumor-targeted ultrasound imaging and ultrasound-triggered drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2016;108:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ke CJ, Chiang WL, Liao ZX, et al. Real-time visualization of pH-responsive PLGA hollow particles containing a gas-generating agent targeted for acidic organelles for overcoming multi-drug resistance ☆. Biomaterials. 2013;34(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kircher MF, Gambhir SS, Jan G. Noninvasive cell-tracking methods. Nat Reviews Clin Oncol. 2011;8(11):677–688. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kircher MF, Willmann JK. Molecular body imaging: MR imaging, CT, and US. part I. principles. Radiology. 2012;263(3):633–643. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12102394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang P, Yong F, Lu L, et al. NIR-II nanoprobes in-vivo assembly to improve image-guided surgery for metastatic ovarian cancer. Nature Comm. 2018;9(1):2898. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05113-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng L, Sixiang S, Chao L, et al. Iron oxide decorated MoS2 nanosheets with double PEGylation for chelator-free radiolabeling and multimodal imaging guided photothermal therapy. Acs Nano. 2015;9(1):950–960. doi: 10.1021/nn506757x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai W, Gao H, Chu C, et al. Engineering phototheranostic nanoscale metal-organic frameworks for multimodal imaging-guided cancer therapy. Acs Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(3):2040–2051. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b11579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atabaev TS. PEG-coated superparamagnetic dysprosium-doped Fe3O4 nanoparticles for potential MRI imaging. BioNanoScience. 2018;8(1):299–303. doi: 10.1007/s12668-017-0447-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thapa B, Diaz-Diestra D, Beltran-Huarac J, Weiner BR, Morell G. Enhanced MRI T2 relaxivity in contrast-probed anchor-free PEGylated iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res Letters. 2017;12(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s11671-017-2084-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li M, Bu W, Jie R, et al. Enhanced synergism of thermo-chemotherapy for liver cancer with magnetothermally responsive nanocarriers. Theranostics. 2018;8(3):693–709. doi: 10.7150/thno.21297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai J, Wang JT, Rubio N, et al. Triple-modal imaging of magnetically-targeted nanocapsules in solid tumours In Vivo. Theranostics. 2016;6(3):342–356. doi: 10.7150/thno.11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin X, Xu C, Kohler N, Hou Y, Sun S. Controlled PEGylation of monodisperse Fe3O4 nanoparticles for reduced non-specific uptake by macrophage cells. Adv Materials. 2010;19(20):3163–3166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Luo Y, Xu Y, et al. Conjugation of iron oxide nanoparticles with RGD-modified dendrimers for targeted tumor MR imaging. Acs Appl Materials Interfaces. 2015;7(9):5420. doi: 10.1021/am508983n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jingchao L, Yao H, Wenjie S, et al. Hyaluronic acid-modified hydrothermally synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles for targeted tumor MR imaging. Biomaterials. 2014;35(11):3666–3677. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi J, Chen C, Zhang X, et al. Light-driven transformable optical agent with adaptive functions for boosting cancer surgery outcomes. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):1848. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung S, O’Shea DF. Directed self-assembly of fluorescence responsive nanoparticles and their use for real-time surface and cellular imaging. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1):1885. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caruana I, Savoldo B, Hoyos V, et al. Heparanase promotes tumor infiltration and antitumor activity of CAR-redirected T lymphocytes. Nature Med. 2015;21:524. doi: 10.1038/nm.3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Q, Xu L, Liang C, Wang C, Peng R, Liu Z. Photothermal therapy with immune-adjuvant nanoparticles together with checkpoint blockade for effective cancer immunotherapy. Nature Communications. 2016;7:13193. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko J, Park K, Kim YS, et al. Tumoral acidic extracellular pH targeting of pH-responsive MPEG-poly(β-amino ester) block copolymer micelles for cancer therapy. J Controlled Release. 2007;123(2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heebeom K, Hyejung L, Sojin L, et al. In vivo tumor diagnosis and photodynamic therapy via tumoral pH-responsive polymeric micelles. Chemical Communications. 2010;46(31):5668–5670. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01413c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, Xu F, Wang Y, Liu X, Jin Q, Ji J. pH-responsive and biodegradable polymeric micelles based on poly(β-amino ester)-graft-phosphorylcholine for doxorubicin delivery. Polymer Chemistry. 2013;4(10):3012–3019. doi: 10.1039/c3py00139c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard LP, Jonathan C, Klibanov AL, Sanjiv K, Lindner JR. Noninvasive assessment of angiogenesis by ultrasound and microbubbles targeted to alpha(v)-integrins. Circulation. 2003;41(6):430–431. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044916.05919.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Feng M, Gang N, et al. 68Ga-BBN-RGD PET/CT for GRPR and integrin αvβ3 imaging in patients with breast cancer. Theranostics. 2018;8(4):1121–1130. doi: 10.7150/thno.22601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qing-Hui Z, Ye-Zi Y, Chao W, Yi H, David O. Cyclic RGD-targeting of reversibly stabilized DNA nanoparticles enhances cell uptake and transfection in vitro. J Drug Targeting. 2009;17(5):364. doi: 10.1080/10611860902807046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu Y, Zhang J, Meng F, et al. cRGD-functionalized reduction-sensitive shell-sheddable biodegradable micelles mediate enhanced doxorubicin delivery to human glioma xenografts in vivo. J Controlled Release. 2016;233:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;10(1):9. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo L, Zhong H, Liu S, et al. Intracellular “activated” two-photon photodynamic therapy by fluorescent conveyor and photosensitizer co-encapsulating pH-responsive micelles against breast cancer. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12(12):5189–5201. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S140345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lau JTF, Pui-Chi L, Xiong-Jie J, Qiong W, Ng DKP. A dual activatable photosensitizer toward targeted photodynamic therapy. J Med Chem. 2014;57(10):4088–4097. doi: 10.1021/jm500456e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The conclusions made in this manuscript are based on the data which are all presented and shown in this paper.