Emerging infections cause justifiable global concern. Current outbreaks of avian influenza A H7N91 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)2 raise troubling memories of pandemic influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). With few mutations,3, 4, 5 these or other pathogens could evolve to cause widespread outbreaks.

When new threats emerge, well established public health systems rapidly identify cases and evaluate sources, clinicians provide early descriptive case reports, and laboratories develop diagnostics and characterise pathogens. Clinical science is markedly less agile. We lack the tools to answer key questions rapidly. Who is susceptible, and why? What are the mechanisms of disease? What are the sites and dynamics of pathogen replication? How can early cases be identified and stratified? What is the clinical utility of new diagnostics? What treatments might work?

Each emerging infection presents these fundamental questions. The method of answering them need not be reinvented from one infection to the next. If clinical scientists across the world were able to agree on methods and cooperate, the results of separate studies from diverse locations and conditions could be collated, allowing clinically useful conclusions to be reached from shared data.

The International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC)6 grew from the recognition that we have to do things differently, in the light of our experience during the epidemics of SARS, H5N1, and the 2009–10 influenza pandemic, but also regional epidemics of enterovirus 71, dengue, viral haemorrhagic fevers, and even during the rapid emergence of drug resistant malaria.7 We must motivate and equip individual investigators and networks around the world to work together to rapidly answer basic questions when new threats emerge. Academic credit and access to data and samples must be given to clinical investigators, who often recruit patients in extremely challenging circumstances. Unlike the existing model that prioritises independence, effective collaboration should be rewarded. The core materials needed to enrol patients must be freely available, making it as easy as possible for investigators at the front line.

The core materials of clinical research—protocols, information sheets, consent forms, and case report forms—are analogous to the source code of computer software. In open-source software projects contributors receive recognition that builds their reputation within the software community. We propose a similar approach to clinical research, in parallel with the drive towards open access in academic publishing.8 Although community projects have a long history in other fields, individual recognition is required for scientists to obtain funding and promotion; to succeed, academic institutions, funders, journals, the clinical science and public health communities, and the public need to be in full support.

To develop a consensus set of documentation, we engaged with investigators across countries and disciplines, in collaboration with WHO, in a systematic three-stage process: first, to agree criteria by which to prioritise and stratify studies; second, to identify important unanswered questions relating to pathogenesis, susceptibility, and pharmacology in severe infection; and to allocate studies within a globally scalable framework.

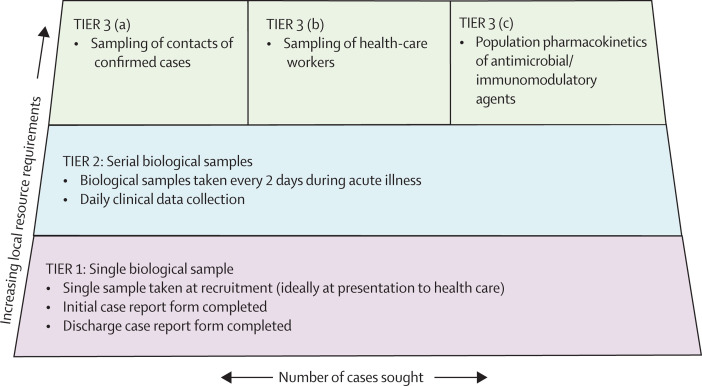

In the resulting protocol, research intensity is stratified according to the local costs incurred. The lowest tiers have a minimum requirement for staff and resources to recruit a case (figure ), enabling adaptation for use in places with differing resource levels, and also in different phases of an outbreak. For example, early in an outbreak there are urgent questions that require intensive study of a small number of cases; later, when larger numbers of cases present, it will be both more difficult and less important to obtain frequent serial samples.

Figure.

Stratified, modular framework of research studies enabling recruitment in a range of different conditions

ISARIC aims to reach a global consensus behind collection of harmonised clinical data linked with biological sampling protocols that are of value to anyone facing future outbreaks of any emerging infection. Importantly, our recommendations are not to be regarded as fixed and final, but an initial contribution to an evolving framework of research studies to which anyone, anywhere, may contribute and improve, and which will be openly shared in perpetuity.

We regard this consensus as essential but not sufficient. Here we lay the foundations for more challenging coordinated studies, including clinical trials of pathogen-specific therapies with pragmatic endpoints. We encourage clinicians everywhere to develop and share appropriate research protocols and seek approvals for clinical research that can begin immediately as soon as future epidemics threaten. Experience confirms that the time to act is now.

For the full list of contributors, affiliations, and acknowledgments, see appendix.

Acknowledgments

SHL has received research grants, travel bursaries, speakers honoraria, and support for HIV & hepatitis drug interaction websites from Merck, Janssen, Gilead Sciences, BristolMyersSquibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, AbbVie, and ViiV Healthcare. JPC is Director of the US Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group, and receives some salary support and contract funding from the US Government's Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1888–1897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herfst S, Schrauwen EJA, Linster M. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science. 2012;336:1534–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature. 2012;486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309:1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yong E. Trials at the ready: preparing for the next pandemic. BMJ. 2012;344:e2982. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran TH, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Hayden FG, Farrar J. Patient-oriented pandemic influenza research. Lancet. 2009;373:2085–2086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulton G, Rawlins M, Vallance P, Walport M. Science as a public enterprise: the case for open data. Lancet. 2011;377:1633–1635. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60647-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.