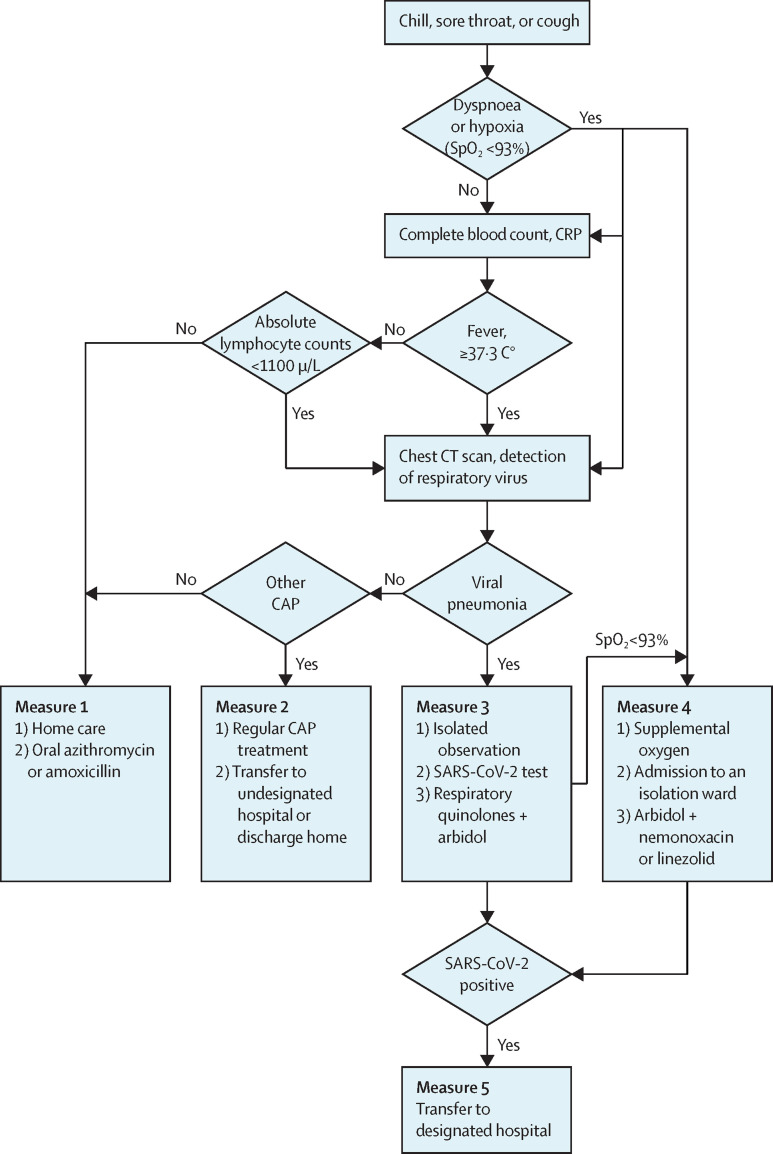

In December, 2019, numerous unexplained pneumonia cases occurred in Wuhan, China. This outbreak was confirmed to be caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), belonging to the same family of viruses responsible for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).1 The SARS epidemic in 2003 was controlled through numerous measures in China. One effective strategy was the establishment of fever clinics for triaging patients. Based on our first-hand experience in dealing with the present outbreak in Wuhan, we have established the following clinical strategies in adult fever clinics (figure ).

Figure.

Flow chart for treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus disease in fever clinics in Wuhan China

CRP=C-reactive protein. CAP=Community-acquired pneumonia. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2.

Patients can be afebrile in the early stages of infection, with only chills and respiratory symptoms. High temperature is not a general presentation. Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) is an important factor of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19; formally known as 2019-nCoV) and impaired immunity, characterised by lymphopenia, is an essential characteristic. Therefore, in afebrile patients (temperature <37·3°C) without dyspnoea, we recommend measurements of complete blood count and CRP. Subsequently, if the lymphocyte concentration is ≥1100/μL, home care with self-isolation is advised. Oral azithromycin or amoxicillin can be prescribed (measure 1, figure).

Chest CT is helpful (appendix) and is more sensitive than x-ray in identifying viral pneumonia. Imaging of patients with COVID-19 initially revealed characteristic patchy infiltration, progressing to large ground-glass opacities that often present bilaterally. The differential diagnosis for viral pneumonia includes respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus. Febrile patients (temperature ≥37·3°C) should have both chest CT and respiratory viral tests. Patients with normal chest CT scans can follow measure 1 interventions. If the consensus is bacterial community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), then standard clinical protocols are followed. Once the patient's temperature returns to normal, they are transferred to undesignated hospitals or discharged home (measure 2, figure).

Patients diagnosed with viral pneumonia require isolation and SARS-CoV-2 tests (measure 3). Systemic and local respiratory defense mechanisms are compromised, resulting in bacterial co-infection if early, effective antiviral treatment is not started. Empirical therapy consists of oral moxifloxacin or levofloxacin (consider tolerance) and arbidol. Arbidol is approved in China and Russia for influenza treatment. In-vitro studies showed that arbidol had inhibitory effects on SARS.2 Patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 are transferred to designated hospitals.

Dyspnoea and hypoxaemia suggest severe pneumonia and are suspicious even in afebrile patients. If presenting with dyspnoea and hypoxia (oxygen saturation [SpO2] <93%), prescribe supplemental oxygen, admit to an isolation ward, and assess transfer risk. If patients are deteriorating with measure 3 interventions, the core treatment principle we recommend is antiviral plus antipneumococcus plus anti-Staphylococcus aureus (measure 4, figure). Coverage for Streptococcus pneumoniae and S aureus is important as co-infection increases the likelihood of severe illness.3 High-dose nemonoxacin (750 mg once daily) and linezolid is effective against S pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]).

Glucocorticoids are not a routine treatment.4 In emergency cases, such as SpO2 <90%, dexamethasone 5–10 mg or methylprednisolone 40–80 mg is given intravenously before transfer. High-throughput oxygen therapy or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ventilation are both effective supportive therapies and target blood SpO2 should be 88–90%. Invasive mechanical ventilation is used as a last resort.

Special considerations are given for elderly, immunocompromised, and pregnant patients. Older patients (>65 years) and immunocompromised patients should be treated as moderate or severe cases in the initial assessment. Infections in pregnant women might progress rapidly and timely clinical decisions are crucial to provide pregnant women with options, such as induction, anaesthesia, and surgery. Consultation with an obstetric specialist is recommended and depending on the condition of the mother, termination of the pregnancy is a consideration.

Home care and isolation can relieve the burden on health-care providers of fever clinics. We used this strategy in Wuhan in response to the large volume of patients arriving at health care centres but do not recommend it for other regions where each suspected case can be appropriately isolated and monitored in a health setting. Inappropriate home care can be life threatening for patients and be a detriment to public health.5

Many factors contributed to developing our clinical algorithm in Wuhan during the early outbreak period. During this time, the influx of patients to fever clinics substantially outweighed the number of physicians. Inpatient care was unsafe due to potential cross-infection and supplementary resources were not ready. Applying and waiting for results of an SARS-CoV-2 test was time consuming just after the outbreak and did not aid clinical decision making. We made trade-offs between infection control and standard medical principles and adapted the protocol as more information and resources became available. We hope our experience will serve as guidance for other fever clinics and future cases.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khamitov RA, Loginova S, Shchukina VN, Borisevich SV, Maksimov VA, Shuster AM. Antiviral activity of arbidol and its derivatives against the pathogen of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the cell cultures. Vopr Virusol. 2008;53:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hageman JC, Uyeki TM, Francis JS. Severe community-acquired pneumonia due to Staphylococcus aureus, 2003–04 influenza season. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:894–899. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen RC, Tang XP, Tan SY. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with glucosteroids: the Guangzhou experience. Chest. 2006;129:1441–1452. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Home care for patients with suspected novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection presenting with mild symptoms and management of contacts. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/home-care-for-patients-with-suspected-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-presenting-with-mild-symptoms-and-management-of-contacts

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.