Abstract

Background:

Breastfeeding rates of incarcerated women in the United States are unknown but are likely to be low. Little is known about the breastfeeding views and experiences of incarcerated women. This exploratory study examined the breastfeeding knowledge, beliefs, and experiences of pregnant women incarcerated in New York City jails.

Methods:

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 20 pregnant women in a New York City jail. Research methods were inspired by grounded theory.

Results:

Three main themes emerged from women’s collective stories about wanting to breastfeed and the challenges that they experienced. First, incarceration removes women from their familiar social and cultural context, which creates uncertainty in their breastfeeding plans. Second, incarceration and the separation from their high-risk lifestyle makes women want a new start in motherhood. Third, being pregnant and planning to breastfeed represent a new start in motherhood and give women the opportunity to redefine their maternal identity and roles.

Conclusions:

Breastfeeding is valued by incarcerated pregnant women and has the potential to contribute to their psychosocial well-being and self-worth as a mother. Understanding the breastfeeding experiences and views of women at high risk for poor pregnancy outcomes and inadequate newborn childcare during periods of incarceration in local jails is important for guiding breastfeeding promotion activities in this transient and vulnerable population. Implications from the findings will be useful to correctional facilities and community providers in planning more definitive studies in similar incarcerated populations.

Keywords: breastfeeding, correctional, incarceration, jail, motherhood, prenatal, qualitative research

Breastfeeding confers numerous health-related benefits to both infants and their mothers. The World Health Organization (WHO) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend that infants should be exclusively breastfed from birth to 6 months of age, barring contraindications (1,2). The nutritional, immunological, developmental, and psychosocial benefits of breastfeeding are well documented (1–4). In addition, breastfeeding can be central to a woman’s experience of motherhood. Successful breastfeeding creates a unique bonding experience between mother and infant and contributes to positive maternal identity and empowerment (5). Incarceration of women who are either current or soon-to-be mothers of young infants may interfere with maternal and infant bonding and breastfeeding, adversely affecting maternal psychosocial well-being and potentially compromising infant health and development (6,7).

In the United States, women of reproductive age are the fastest growing subset of incarcerated persons (8,9). Although approximately two-thirds of female inmates have children aged 8 years or less, correctional programs for young families are lacking and many such families experience the consequences of extended separation periods (10–12). Forced separation after giving birth, because of incarceration, may create psychological and emotional distress among incarcerated mothers who experience a loss of autonomy and control over aspects of their motherhood (11,13). The establishment of secure attachment between children and their primary caregivers is supported by sustained contact, whereas extended separation places them at greater risk for maladaptive outcomes (6). Infants of incarcerated mothers who experience inconsistent or infrequent maternal contact may be particularly vulnerable to poor social and emotional development (7). In addition, infrequent or inconsistent maternal and child contact, as well as maternal stress or depression because of separation, can inhibit or negatively affect breastfeeding (14–16). However, breastfeeding can alleviate maternal symptoms of stress and depression, promote positive self-image, and enhance bonding with their infants (4,17,18), thus having the potential to foster the maternal–infant relationship and support maternal feelings of self-worth. Limiting maternal and infant separation would enable incarcerated mothers to be consistent caregivers for their infants and would provide their infants with the benefits of breastfeeding. In the United States, however, only nine prison-based and one jail-based nursery programs exist; thus, most incarcerated mothers do not have the option to reside with or breastfeed their newborn infants (19,20).

Breastfeeding rates of formerly or currently incarcerated women in the United States are unknown, but are likely to be low. In addition to separation from their children, which can adversely affect breastfeeding, incarcerated women often belong to racial or ethnic minorities, have low educational attainment and socioeconomic status, lack social support, and receive limited prenatal care, all of which are associated with low breastfeeding initiation and duration (8,10,21–25). In addition, they have a high prevalence of illicit drug use and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, which in the United States are contraindications to breastfeeding (24,26). These factors also place incarcerated pregnant women at risk for adverse birth outcomes and poor infant health (27,28).

Little is known about the breastfeeding views and experiences of incarcerated women. This exploratory study examined the breastfeeding knowledge, beliefs, and experiences of pregnant women incarcerated in New York City jails.

Methods

Setting

Interviews were conducted at the New York City Rikers Island Jail’s Rose M. Singer Center from July 2007 to June 2008 (study period) using a protocol approved by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Institutional Review Board. The Rose M. Singer Center typically houses female pretrial detainees and women sentenced to 1 year or under. In 2006, 428 pregnant women were housed in New York City jails, 60 percent of whom were black, 21 percent Hispanic, 14 percent white, and 5 percent of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. The Rose M. Singer Center includes a prenatal clinic and the only jail-based nursery program in the United States. Incarcerated pregnant women receive breastfeeding education and literature at the prenatal clinic, along with comprehensive prenatal services, and are encouraged to apply for the jail nursery program.

Women are transferred to a nearby hospital to deliver their infants and receive maternal care according to the hospital’s policy. The hospital follows the Baby-Friendly Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding for hospitals and thus provides breastfeeding counseling and, unless contraindicated as a result of maternal criminal charges, allows rooming-in of newborns. Postpartum incarcerated women who are enrolled in the jail’s nursery program are eligible to reside with their infants for up to 1 year. The jail nursery provides breastfeeding counseling and equipment; supports bonding and attachment; promotes parenting skills; and provides health education and discharge planning. Infants of women not enrolled in the jail nursery program are cared for by designated legal guardians or are placed in foster care.

Sample and Data Collection

The principal investigator (K. Huang) designed the research methods, recruited participants, and conducted all interviews. Study eligibility criteria included women who were pregnant at time of incarceration, aged 18 years or older, and proficient in English. A purposeful sampling method of selecting women was used to reflect the racial and ethnic proportions of pregnant women at the Rose M. Singer Center. Women were enrolled in the prenatal clinic waiting area, and informed consent was obtained for participants. Reasons for declining enrollment were not obtained for ethical considerations. Women who offered an explanation for declining stated that they were not interested or that they would not be available to participate.

Semistructured interviews and questionnaire modifications were simultaneously conducted to achieve an inductive and flexible research process to explore the research question. Although all interviews used a semistructured questionnaire, researchers modified or added questions to explore emerging topics. Interviews were conducted in a private space to protect confidentiality and ranged from 30 to 85 minutes in length with a mean of 56 minutes. The process continued until information saturation was reached (e.g., no new information was obtained during the interviews). Participants were asked about sociodemographic information, number of living children, pregnancy status, previous prenatal care, and previous smoking and/or illicit drug use (Table 1). Women with living children were asked about their previous infant feeding histories and current infant feeding plans; responses were categorized into intentions to breastfeed, formula feed, or being undecided at the time of the interview (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Interview Participants, New York City Jails, 2007–2008

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) (n = 20) | |

| <20 | 3 (15) |

| 20–24 | 4 (20) |

| 25–29 | 5 (25) |

| 30–34 | 3 (15) |

| >34 | 5 (25) |

| Race/ethnicity* (n = 20) | |

| Black | 9 (45) |

| Hispanic | 7 (35) |

| Other | 4 (20) |

| Education completed (n = 19) | |

| Some high school | 6 (32) |

| High school | 4 (21) |

| Some college | 5 (26) |

| College | 4 (21) |

| Marital status (n = 20) | |

| Single | 5 (25) |

| Married | 6 (30) |

| Partner | 7 (35) |

| Widow | 2 (10) |

| Gestation at interview (n = 20) | |

| First trimester | 2 (10) |

| Second trimester | 14 (70) |

| Third trimester | 4 (20) |

| Prior prenatal care† (n = 19) | |

| Yes | 9 (47) |

| No | 10 (53) |

| Living children (n = 20) | |

| 0 | 5 (25) |

| 1 | 4 (20) |

| 2 | 4 (20) |

| 3+ | 7 (35) |

| Smoking (n = 16) | |

| Yes | 11 (69) |

| Quit‡ | 3 (19) |

| No | 2 (12) |

| Drug use (n = 12) | |

| Yes | 9 (75) |

| Quit‡ | 1 (8) |

| No | 2 (17) |

| Low income§ (n = 17) | |

| Yes | 15 (88) |

| No | 2 (12) |

Report of both Hispanic and black/other women were recorded as Hispanic.

Before incarceration.

Stopped use during current pregnancy.

Defined by a history of enrollment in the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) supplemental nutrition program for low-income families.

Table 2.

Breastfeeding and Demographic Information of Interview Participants, New York City Jails, 2007–2008

| Woman No. | Infant Feeding History* | Infant Feeding Plan | Age (yr) | Living Children | Race/Ethnicity† | Marital Status | Education | Smoker‡ | Drug Use‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | 30–34 | 4 | Other | Married | Some high school | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Attempted breastfeeding | Undecided | 25–30 | 1 | Black | Partner | NR | NR | NR |

| 3 | Breastfeeding | Formula | >34 | 5 | Hispanic | Partner | High school | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | Not applicable | Breastfeeding | 20–24 | 0 | Hispanic | Married | Some college | Yes | NR |

| 5 | Attempted breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | >34 | 4 | Black | Married | Some high school | Yes | NR |

| 6 | Attempted breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | <20 | 1 | Hispanic | Married | Some high school | Yes | NR |

| 7 | Formula | Breastfeeding | >34 | 2 | Black | Single | Some college | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Attempted breastfeeding | Formula | >34 | 5 | Black | Widow | High school | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Breastfeeding | Formula | 25–30 | 1 | Hispanic | Single | College | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Not applicable | Undecided | 20–24 | 0 | Hispanic | Partner | Some college | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | 25–30 | 2 | Other | Married | Some college | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | Not applicable | Breastfeeding | 25–30 | 0 | Black | Widow | College | No | No |

| 13 | Not applicable | Breastfeeding | <20 | 0 | Black | Partner | College | NR | NR |

| 14 | Breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | >34 | 3 | Black | Married | College | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | Formula | Breastfeeding | 20–24 | 2 | Black | Single | High school | No | No |

| 16 | Attempted breastfeeding | Formula | 30–34 | 3 | Black | Single | Some high school | Yes | NR |

| 17 | Breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | 20–24 | 1 | Other | Partner | Some high school | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Not applicable | Breastfeeding | <20 | 0 | Other | Partner | Some college | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | Formula | Formula | 25–30 | 2 | Hispanic | Single | High school | NR | NR |

| 20 | Breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | 30–34 | 3 | Hispanic | Partner | Some high school | NR | NR |

Breastfeeding = duration > 2 weeks and attempted = duration ≤ 2 weeks.

Report of black/other race and Hispanic ethnicity were recorded as Hispanic.

Smoking and drug use before incarceration.

NR = not reported.

Open-ended questions provided an initial guide for exploration of women’s breastfeeding experiences, beliefs, and knowledge; examples of interview questions were “What were your past breastfeeding experiences like?” “What are the benefits and disadvantages of breastfeeding?” and “Who or where do you go to for infant feeding information?” Although women’s feelings and perceptions about their knowledge, proficiency, and confidence in breastfeeding were explored from the first interview, scale questions were included from the sixth interview to further prompt and explore related emerging topics and themes and to capture women’s intensity of feeling or level of agreement about them (Table 3). Sensitive topics such as substance use were explored only when disclosed by participants.

Table 3.

Breastfeeding Scale Questions of Interview Participants, New York City Jails, 2007–2008

| Topics | Questions | No.* | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance | 1 = not very important; 10 = very important How important or not important is it for you to breastfeed this baby? |

10 | 8 | 1–10 |

| Confidence | 1 = not very confident; 10 = very confident How confident do/would you feel about your ability to breastfeed? |

13 | 6 | 1–10 |

| Proficiency | 1 = very difficult; 10 = very easy How easy or difficult do you think breastfeeding would be? |

14 | 5 | 1–9 |

| Knowledge | 1 = not very knowledgeable; 10 = very knowledgeable How would you rate your level of knowledge about breastfeeding? |

12 | 5 | 1–9 |

| Outcome | 1 = not very good; 10 = very good If you were to breastfeed this baby, how would you rate how breastfeeding would turn out? |

11 | 8 | 5–10 |

Frequencies vary as a result of scale questions being asked to prompt discussion when relevant.

Data Analysis

Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy before importing into ATLAS.ti 5.2 for analysis (29). Qualitative methods inspired by the grounded theory approach, which involves the systematic and inductive generation of theory from data, were used for the analysis (30–32). Transcribed interviews, field notes, and analysis memos were used to identify codes, categories, and themes. Open coding identified key events and concepts that were linked to words, sentences, or paragraphs in the text. Similar and repetitive codes were grouped into categories, which were used to generate themes. Themes reflected the relationship between codes and categories and led to theory development that explained incarcerated women’s collective experience about breastfeeding.

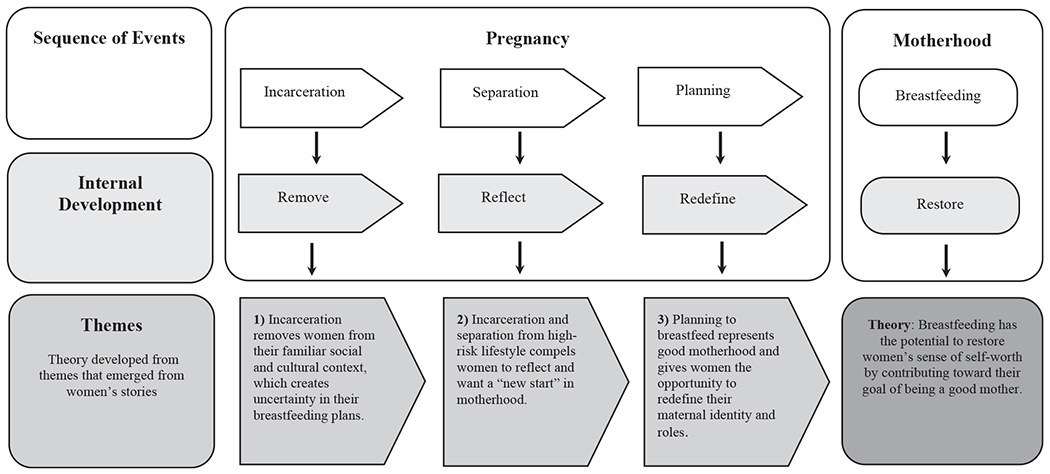

All interviews were independently coded and categorized by two researchers, one who recruited women and conducted all of the interviews and another who was not involved in the recruiting or interviewing processes. Multiple research team meetings were held to discuss and ensure identification of all relevant codes and categories; discrepancies were resolved by referring back to the interviews, field notes, and memos until a list of codes and categories were modified or agreed on. Subsequently, the two researchers independently identified the themes; disagreements were resolved in team meetings by discussing the relationships among codes, categories, and themes until consensus was reached. The use of a story framework supported the integration of the main themes to develop a theory that represented the women’s collective experiences (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Breastfeeding themes as described by incarcerated pregnant women, New York City Jails, 2007–2008.

Results

During the study period, 28 pregnant women (50% of those recruited) consented to study participation, of whom 20 (71%) were interviewed; 8 (29%) had schedule conflicts or were discharged from jail. Data were not collected on women who declined participation. Of 20 women, 16 (80%) identified themselves as black or Hispanic (Table 1). More than 80 percent of women for whom data were available reported cigarette smoking and illicit drug use before their current pregnancy. In addition, women reported current mental health issues (n = 2) and histories of homelessness (n = 4), domestic violence (n = 2), and childhood sexual or physical abuse (n = 1). More than 50 percent had no prenatal care before incarceration and six (30%) were informed of their pregnancy at jail admission. Thirteen women reported that they planned to breastfeed and an additional three women stated that they would have chosen to breastfeed if they were not HIV-positive (Table 2).

For women with breastfeeding experience, the most commonly reported challenges related to difficulties in latching, pain, concerns about breastfeeding in public, and separation from infants (because of school, work, custody issues, and previous incarceration). Past reasons for choosing to formula feed included substance use, poor maternal health, convenience, and lack of breastfeeding knowledge (e.g., proper latching techniques and contraindications for breastfeeding). Women who were asked to quantify self-perceived breastfeeding knowledge, proficiency, and confidence levels reported a median rating of 5, 5, and 6, respectively, on a scale of 1 to 10 (Table 3). Almost all women reported receiving some breastfeeding education from family or community supports before incarceration; however, most reported wanting to learn more about breastfeeding techniques, pumping, and weaning, and many had misconceptions about how routine illnesses and substances, such as tobacco and commonly used medications, affect breastmilk.

The interviews explored breastfeeding in the context of incarcerated pregnant women’s past, present, and future, and revealed a collective story about their wanting to breastfeed as a way to actively participate in motherhood. Three significant themes emerged leading to an overall theory about the meaning of breastfeeding. Women’s stories were organized into two sections: “Sequence of Events” (incarceration, separation, planning, and breastfeeding) and their corresponding “Internal Developments” (remove, reflect, redefine, and restore). Each event followed by its internal development combined to form the basis for each theme (Fig. 1).

Theme 1: Incarceration Removes Women from their Familiar Social and Cultural Context, which Creates Uncertainty in their Breastfeeding Plans

Incarceration created uncertainties by removing expectant mothers from their familiar and supportive context and prevented them from having control over aspects of their lives. Women were anxious about the potential for separation from their infants and losing the ability to breastfeed.

Removal from social supports

Women spoke about the importance of social supports in their past breastfeeding experiences. All but one women reported female family members as their primary source of breastfeeding support and valued their knowledge and influence. Women also reported other sources of support, such as their partners, health professionals, and maternal–child programs in the community. Incarceration removes women from their valued supports.

Separation from infant

Women’s confidence in their breastfeeding plans was affected by their concern about being separated from their infants. Many were uncertain of the outcome of their custody issues and potential duration of incarceration. They also worried that, after jail release, their need to return to work or plans to attend school would hinder breastfeeding. Some women shared their concern that breastfeeding caused their infants to become “too attached,” making separation and weaning difficult. Those who anticipated having to be separated from their infants planned to mix feed with formula and breastmilk or shorten the duration of breastfeeding to avoid future weaning problems.

Babies that are breastfed get more attached to the mother and then when the momma’s not around—it’s hard for the babies because they get so attached. (No. 10)

Theme 2: Incarceration and Separation from High-Risk Lifestyle Compels Women to Reflect and Want a “New Start” in Motherhood

Most of the women spoke about wanting a new start in motherhood. Although being pregnant motivated the women to make positive changes, incarceration and separation from their previous high-risk lifestyle further compelled them to reflect on their lives and desire a better future.

Breastfeeding supports a new start in motherhood

Many women intended to breastfeed as part of their plan for a new start in motherhood. Being pregnant and planning to breastfeed represented the hope that they would return home and have the opportunity to carry out their maternal duties.

I changed. This [incarceration] teached [sic] me a lesson … I tell you that you’re not gonna see my face no more because now I got two kids to deal with … What I need to do is get myself together. (No. 17)

I’m very considering breastfeeding. I think it’s healthy and, being that I’m drug free [during incarceration] … I just want to start something new. (No. 7)

Substance use as a barrier to motherhood and breastfeeding

Women reported that being in jail distanced them from their perceived negative lifestyle and social influences and gave them the opportunity to reflect on how their addictions conflicted with their desire to be good mothers.

I know that if I continue to do the things [drugs] that I used to do … I won’t have a healthy pregnancy or healthy relationship with my baby … I want to be a mother to my child. (No. 7)

Some women viewed their addictions as a moral “vice” that could be physically passed on to their infants and potentially harm their relationship. Women wanted to overcome their substance abuse issues because they believed that the breastmilk their bodies produced is not only naturally healthy, but also vulnerable and easily tainted by substances. In addition to illicit substance use, women were concerned that the intake of substances such as tobacco or caffeine, an unhealthy diet, or routine medications would produce harmful breastmilk. Most women also believed that common illnesses (e.g., upper respiratory illnesses) were contraindicated in breastfeeding. Formula was seen as an alternate or better choice if breastmilk was tainted by use of harmful substances or poor health status.

I don’t want to consume none of those drugs, no alcohol beverages, no cancer smokes or nothing like that because when my baby comes out I want healthy milk … I have to keep those things out of my system. (No. 7)

But to me if you have a fever … and let’s say you have a cold. Whatever it is that you have, you might end up passing it on to the child. (No. 19)

Almost all the women who planned to breastfeed were smokers. However, they often viewed smoking as contraindicated in breastfeeding; as such, their breastfeeding plans were affected by their perceived ability to abstain. Some women shared how their inability to smoke or use illicit substances in jail and their current or anticipated participation in treatment programs gave them hope that they could abstain when they returned home. In addition, one woman discussed the hope that community corrections (e.g., probation) could assist her in abstaining.

When I get out, I wouldn’t smoke because I want to breastfeed, and that is cigarettes and that is weed … Sometimes I hope that I’m on probation to help me out because I’ve been smoking for seven years now. (No. 18)

Jail as a support to motherhood and breastfeeding

Aspects of incarceration were viewed by women as facilitating a new start in motherhood and successful breastfeeding. Expectant mothers were eager to make positive life changes and were receptive to learning about parenting and coping skills. Some women mentioned that the jail-based resources and Rose M. Singer Center nursery program provided helpful maternal health and breastfeeding information.

I see posters on every door about breastfeeding … Well, for me, every time I came to the clinic I thought about breastfeeding. (No. 18)

Women stated that the nursery program was an important resource for them, particularly as they planned a new start as a mother.

It [the nursery] will give me a chance to take on my responsibilities and start out fresh—it has been awhile—and, um, just do things the right way. (No. 16)

Theme 3: Planning to Breastfeed Represents Good Motherhood and Gives Women the Opportunity to Redefine their Maternal Identity and Roles

Women discussed their desire to redefine their maternal identity and roles by planning to breastfeed. They viewed breastfeeding as a symbol of good motherhood; it identified them as mothers and facilitated their maternal roles: to provide for, protect, and bond with their infants.

Breastfeeding contributes to maternal identity

Breastfeeding supported women’s sense of self-worth by identifying them as the one and only mother for their infants, which was especially important for women whose children had multiple caregivers because of frequent separations, as one participant described.

It [breastfeeding] makes me feel special. It makes me feel good to be a woman, because … a man can’t do that … and it’s a blessing. Like, you can not only hold your baby in the womb for nine months and give birth to life, but you can also give your baby vitamins and everything from your own body. (No. 6)

Breastfeeding facilitates maternal roles of provider and protector

Women valued breastfeeding as a way to provide for their infants’ physical health in both specific and metaphorical ways. They believed that breastmilk was the healthiest feeding choice and could provide essential nutrients, vitamins, and antibodies for their infant. Words such as “natural” and “good” were used to describe breastfeeding; in contrast, “synthetic” or “chemical” were used to describe infant formulas.

It’s got to be more healthy because it’s all natural … Those other milks are synthetic … Cows feed their children … We’re the only animal that decided to put something fake in and say, here use this and grow on it. (No. 14)

Women also talked about how breastfeeding protected their infants, for example, from common childhood illnesses. A few mothers had a metaphorical view of how breastfeeding would create a sense of safety for their infants.

He was looking at me, and he was holding my breast, and stuff like that, and I felt like … he felt safe, he felt safe. (No. 9)

In contrast, other women would exercise their role as protector by choosing to formula feed because they believed that their use of substances, smoking, or their poor health would produce harmful breastmilk.

Because their system is so fresh … I just don’t want to take the risk … There are too many new infections and diseases coming out … so it would be … safer to just feed them by bottle. (No. 16)

Women with HIV had a deepened sense of needing to protect their infants. For them, not breastfeeding was seen as a way of fulfilling their maternal role as protector and represented good motherhood.

It affects me because I can’t breastfeed … I can’t, because I have to save the life of my child, because I know the virus is in my body and it’s in my milk. (No. 8)

Breastfeeding facilitates bonding

Almost all women believed breastfeeding was an important and natural way to bond with their infants, making statements such as “to breastfeed is to bond” or “breastfeeding is like a bond you have.” One mother described how breastfeeding also contributed to a sense of healing from her past relationship issues.

That was like my little bit of therapy because I’m adopted. I don’t know my own [mother], so it’s like I never had closeness with the family that raised me, so … I look at breastfeeding as, a kind of therapy. I get to be closer to my child. (No. 11)

Although bottle-feeding was seen by most women as inferior to breastfeeding in facilitating the maternal–infant bond, some women mentioned the advantage that it would give other family members an opportunity to build a relationship with the child. This benefit was particularly important for women who anticipated frequent separations from their infants because of work, school, or custody issues.

The three women with HIV who had previously breastfed viewed bottle-feeding as an adequate way to provide for their infant; however, they grieved for the loss of intimacy that they felt only breastfeeding could establish.

I’m HIV-positive and I cannot breastfeed this baby. It makes me feel very upset … I can’t be as close to my son, because I could infect him, and that makes me feel very bad. (No. 9)

Discussion

To our knowledge, our exploratory study is the first such investigation on breastfeeding knowledge, beliefs, and experiences of incarcerated pregnant women. For those in New York City jails, breastfeeding was talked about in connection with motherhood and had the perceived potential to help restore their maternal identity and sense of self-worth (Fig. 1). Although most women wanted to breastfeed, being incarcerated created uncertainties in their breastfeeding plans. Removal from their familiar social and support context and uncertainty about possible separation from their infants were viewed as barriers to breastfeeding.

Women anticipated needing to be separated from their infants because of incarceration or their need to work or attend school after incarceration. Thus, they planned to mix feed with formula and breastmilk or planned to shorten the duration of breastfeeding to avoid future weaning problems. For those anticipating separation from their infants after incarceration, further research is needed to explore the acceptability and feasibility of using breast pumps to facilitate breastfeeding. For expectant or postpartum mothers facing prolonged incarceration, breastfeeding opportunities are limited. Currently, only one jail-based nursery, nine prison-based nurseries, and approximately a dozen community-based residential parenting programs operate within the nation’s approximate 3,350 jails and 1,650 prisons (9,33). Incarcerated mothers and their infants could benefit from having on-site nurseries or alternatives to incarceration programs to facilitate breastfeeding, bonding, and child development (34). Preventing maternal and infant separation would give incarcerated mothers the opportunity to be a consistent caregiver and provide their infants with the benefits of breastfeeding.

Almost all of the women mentioned their female family members as their most valued support and often sought breastfeeding knowledge and validation from their maternal role models. Comparable findings were reported in a meta-analysis, where female family members were seen as potentially more important than professional or partner support for overcoming breastfeeding challenges (35). In addition, review studies emphasize the decisive role that informal, lay, and professional supports may play in breastfeeding initiation and duration (23,35). Incarceration undermines breastfeeding by separating women from their support system. Further studies are needed to identify ways to support women’s breastfeeding efforts both during incarceration and upon returning to their communities.

The women in our study reported average ratings of breastfeeding knowledge, proficiency, and confidence, suggesting the need for increased education and support. Moreover, less than one-half of the participants accessed prenatal care before incarceration, which may reflect the disparity in access to, and use of, health care by high-risk women. Although some studies have shown adverse pregnancy outcomes of incarcerated females, others suggest that contact with the correctional system during pregnancy may contribute to an increased likelihood of receiving prenatal care and improved birth outcomes (28,36). Incarceration provides a window of opportunity for prenatal care and breastfeeding education and support during a time when expectant or postpartum mothers are vulnerable, yet receptive, to learning and formal supports.

The women were concerned that their health status or substance use would produce breastmilk that was unhealthy or harmful for their infants. Some of these concerns were anticipated from women who were HIV-positive and those with a history of smoking and illicit or prescription drug use, but many women expressed the same concerns for having an unhealthy diet or a common illness. All women believed that smoking was contraindicated in breastfeeding. Studies indicate that maternal smoking may negatively affect breastfeeding intention, initiation, and duration rates (37,38). Nevertheless, although most women were smokers and viewed smoking as a main barrier to breastfeeding, nearly all participants who smoked planned to breastfeed. Comparable with the experiences of women in other studies, our study women expressed feelings of guilt about smoking and wanted to breastfeed to facilitate smoking cessation and positive motherhood (39,40). Similarly, although 50 percent of the women reported illicit drug use before incarceration, many expressed a desire to abstain from substance use after incarceration. The women’s decision to breastfeed provided motivation and hope for overcoming their smoking and drug use habits.

Overall, the desire by study women to provide a “clean” start for themselves and their children was challenged by their belief that breastmilk could be easily tainted by their health status and lifestyle choices. Their concerns about some of their health behaviors and the adverse effects of tobacco or common medications were often not evidence-based contraindications to breastfeeding (41). Moreover, an unhealthy diet and common illnesses are rarely contraindications to breastfeeding, indicating the importance of health practitioners to discuss breastfeeding clearly in relation to routine illnesses, diet, smoking, and medication use to discourage women from unnecessarily withholding breastfeeding (41,42). Furthermore, practitioners should explore possible addiction issues or breastfeeding misconceptions, and consider the possibility that women might be ashamed to discuss their addiction problems or might have beliefs that are not voiced. Successful breastfeeding initiation either during or after incarceration may motivate women to stay drug free after their release and to engage in healthier lifestyles.

The three women with HIV infection revealed their struggle with the irony that breastfeeding reminded them of their potential to be a source of harm to their infants. They were fearful about the possibility of transmitting HIV to their infants and emphasized their duty to protect their infants by choosing not to breastfeed. Protecting children from contracting HIV was also a primary goal reported by HIV-positive women in a recent meta-analysis (43). The HIV-positive women in our study grieved their inability to bond with their infants through breastfeeding. Mothers with HIV in a study by Hebling et al reported similar feelings of grief and incompetence because they were unable to breastfeed; for them, motherhood symbolized a rebirth or a new start in motherhood and gave them a reason to live (44). A study about pregnant women with HIV in New York City revealed how pending motherhood was viewed as a second chance to rectify past mistakes (45). Unlike women who use breastfeeding to foster their sense of self-worth in motherhood, HIV-positive women must find other ways to feel secure in their maternal identity. Further research is required to identify alternate means by which HIV-positive women can bond with their infants and feel positive about their self-efficacy in motherhood.

Our exploratory study has limitations. The breastfeeding views and experiences of a small sample of women in the New York City jail system may not be generalizable to other populations. The women who declined to participate in our study may have had negative views about breastfeeding or planned to formula feed and were hesitant to share their views with the interviewer. As the study population included only women who were proficient in English, it does not represent the breastfeeding experiences of women for whom English is not their primary language. Sensitive topics such as HIV infection or addictions were only discussed when disclosed by participants, thus limiting the interpretation of our data. Scale questions were introduced after some interviews had already been completed to prompt discussion on emerging themes; thus, data may not be generalizable to all the women we interviewed. In addition, the validity of the scale questions in capturing our intent was not assessed, limiting data interpretation. Most jails and prisons do not have on-site nurseries, thereby necessitating the separation of mother and baby on hospital discharge. Incarcerated women who do not have the option to reside with their infants or those serving long sentences in prisons may have different views about breastfeeding and motherhood than the women in our study. Further investigations should be conducted with women in other correctional settings where pregnant women or mothers with young children do not have the option to breastfeed during incarceration. Long-term breastfeeding experiences should be investigated using methodologies such as ethnography or quantitative surveys to complement this study.

Conclusions

Expectant mothers in the New York City jail system shared their belief that breastfeeding represents good motherhood, is the optimal feeding choice, and is important for establishing a close bonding relationship with their infant. Although most planned to breastfeed to achieve a new start in motherhood, they were concerned about the potential of being separated from their infants as a result of incarceration, causing uncertainties about their ability to breastfeed. Women were conflicted about how their health status and substance use problems might prevent them from breastfeeding. As breastfeeding offers multiple benefits to women and their children, correctional on-site nurseries and alternatives to incarceration programs can provide valuable breastfeeding supports and facilitate women’s connection to maternal–child resources in the community. For women with true contraindications to breastfeeding, alternate means of promoting maternal–infant bonding should be supported. Partnering with incarcerated women to address the barriers and contraindications to breastfeeding can foster their goal for a restored motherhood.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the women who shared their stories with us. We thank Jason Hershberger, Louise Cohen, and Maria Gbur for their support and advocacy; Erik Berliner and the New York City Department of Correction staff for their operational support; Michele McNeill, Sonya Pittman, Crystal Alford, and Eliott Jones of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Office of Correctional Public Health for their valuable assistance in data management; the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Institutional Review Board for their guidance on ethics in research; Pia Olsson of Uppsala University for insight and encouragement; Elizabeth Kilgore for research guidance; and Debra Waldoks for assistance with the New York City jail breastfeeding initiatives.

References

- 1.Butte NF, Lopez-Alarcon MG, Garza C, eds. Nutrient Adequacy of Exclusive Breastfeeding for the Term Infant During the First Six Months of Life. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2005;115(2):496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.León-Cava N, Lutter C, Ross J, Martin L. Quantifying the Benefits of Breastfeeding: A Summary of the Evidence. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klaus M. Mother and infant: Early emotional ties. Pediatrics 1998;102(5 Suppl E):1244–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmied V, Barclay L. Connection and pleasure, disruption and distress: Women’s experience of breastfeeding. J Hum Lact 1999;15(4):325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dallaire DH. Children with incarcerated mothers: Developmental outcomes, special challenges and recommendations. J Appl Dev Psychol 2007;28(1):15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poehlmann J Representations of attachment relationships in children of incarcerated mothers. Child Dev 2005;76(3):679–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabol WJ, Minton TD, Harrison PM. Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2006 [Online] Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, 2007, NCJ 217675; Accessed August 2, 2011 Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephan JJ. Census of Jails, 1999 [Online] Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, 2001, NCJ 186633; Accessed August 2, 2011 Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkauskas VH, Low LK, Pimlott S. Health outcomes of incarcerated pregnant women and their infants in a community-based program. J Midwifery Women’s Health 2002;47(5): 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safyer SM, Richmond L. Pregnancy behind bars. Semin Perinatol 1995;19(4):314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poehlmann J Incarcerated mothers’ contact with children, perceived family relationships, and depressive symptoms. J Fam Psychol 2005;19(3):350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogel CI, Belyea M. Psychological risk factors in pregnant inmates. A challenge for nursing. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2001;26(1):10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coles J Qualitative study of breastfeeding after childhood sexual assault. J Hum Lact 2009;25(3):317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasselmann MH, Werneck GL, Silva CV. Symptoms of postpartum depression and early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding in the first two months of life. Cad Saude Publica 2008;24(Suppl 2):S341–S352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pippins JR, Brawarsky P, Jackson RA, et al. Association of breastfeeding with maternal depressive symptoms. J Womens Health 2006;15(6):754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groër MW. Differences between exclusive breastfeeders, formula-feeders, and controls: A study of stress, mood, and endocrine variables. Biol Res Nurs 2005;7(2):106–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mezzacappa ES, Katlin ES. Breast-feeding is associated with reduced perceived stress and negative mood in mothers. Health Psychol 2002;21(2):187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenfeld LA, Snell TL. Women Offenders [Online] Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, 1999, NCJ 175688; Accessed December 2, 2011 Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villanueva CV, B SB, Lerner GL. Mothers, Infants and Imprisonment: A National Look at Prison Nurseries and Community-Based Alternatives [Online] New York, NY: Women’s Prison Association, 2009. Accessed August 2, 2011 Available at: http://www.wpaonline.org. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Covington SS. Women and the criminal justice system. Women’s Health Issues 2007;17(4):180–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitra AK, Khoury AJ, Hinton AW, Carothers C. Predictors of breastfeeding intention among low-income women. Matern Child Health J 2004;8(2):65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennis CL. Breastfeeding initiation and duration: A 190–2000 literature review. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2002;31(1): 12–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karberg JC, James DJ. Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002 [Online] Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, 2005, NCJ 209588; Accessed August 2, 2011 Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durrah TL, Rosenberg TJ. Smoking among female arrestees: Prevalence of daily smoking and smoking cessation efforts. Addict Behav 2004;29(5):1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altice FL, Marinovich A, Khoshnood K, et al. Correlates of HIV infection among incarcerated women: Implications for improving detection of HIV infection. J Urban Health 2005;82 (2):312–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mertens DJ. Pregnancy outcomes of inmates in a large county jail setting. Public Health Nurs 2001;18(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ, Huebner CE, et al. Perinatal health service use by women released from jail. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2004;15(3):426–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ATLAS.ti GmbH ATLAS.ti (Version 5.2) [Software]. Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2007. Accessed August 2, 2011 Available at: http://www.atlasti.com. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strauss AS, Corbin JC. Grounded theory methodology: An overview In: Bryman AB, Burgess RB, eds. Qualitative Research: Part Three Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 1999:72–93. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heath H, Cowley S. Developing a grounded theory approach: A comparison of Glaser and Strauss. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41 (2):141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neill SJ. Grounded theory sampling: the contribution of reflexivity. J Res Nurs 2006;11(3):253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephan JJ, Karberg JC. Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2000 [Online] Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, 2003, NCJ 198272; Accessed August 2, 2011 Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruns DA. Promoting mother–child relationships for incarcerated women and their children. Infants Young Child 2006;19(4):308–322. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McInnes RJ, Chambers JA. Supporting breastfeeding mothers: Qualitative synthesis. J Adv Nurs 2008;62(4):407–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kyei-Aboagye K, Vragovic O, Chong D. Birth outcome in incarcerated, high-risk pregnant women. J Reprod Med 2000;45 (3):190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horta BL, Kramer MS, Platt RW. Maternal smoking and the risk of early weaning: A meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 2001;91(2):304–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amir LH, Donath SM. Does maternal smoking have a negative physiological effect on breastfeeding? The epidemiological evidence Birth 2002;29(2):112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Irwin LG, Ratner PA. Narratives of smoking relapse: The stories of postpartum women. Res Nurs Health 2000;23(2):126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards N, Sims-Jones N. Smoking and smoking relapse during pregnancy and postpartum: Results of a qualitative study. Birth 1998;25(2):94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ressel G AAP updates statement for transfer of drugs and other chemicals into breast milk. American Academy of Pediatrics. Am Fam Physician 2002;65(5):979–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorea JG. Maternal smoking and infant feeding: Breastfeeding is better and safer. Matern Child Health J 2007;11(3):287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Res Nurs Health 2003;26(2):153–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hebling EM, Hardy E. Feelings related to motherhood among women living with HIV in Brazil: A qualitative study. Aids Care 2007;19(9):1095–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanders LB. Women’s voices: The lived experience of pregnancy and motherhood after diagnosis with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2008;19(1):47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]