Abstract

Objectives:

To examine parent perception of how the physical and cultural environment of the pediatric intensive care unit impacted the implementation of family-centered care as outlined by the Institute for Patient and Family Centered Care.

Research Design:

A qualitative descriptive design utilizing secondary analysis from a longitudinal study. Sixty-one interviews with 3 mothers and 3 fathers (31 interviews with mothers, 30 interviews with fathers) of infants with complex congenital heart defects treated in a pediatric intensive care unit were subjected to secondary analysis via content analysis. The previously completed individual interviews with parents took place at least monthly ranging from soon after birth of their infant to one year of age or infant death, whichever occurred first.

Findings:

The family-centered care core concepts of information sharing, participation, respect and dignity were present in parent interviews. Parents indicated that the physical and cultural environment of the pediatric intensive care unit impacted their perceptions of how each of the core concepts was implemented by clinicians. The unit environment both positively and negatively impacted how parents experienced their infant’s hospitalization.

Conclusion:

In the pediatric intensive care unit, family centered care operationalized as policy differed from actual parent experiences. The impact of the physical and cultural environment should be considered in the delivery of critical care, as the environment was shown to impact implementation of each of the core concepts.

Keywords: Environment, Family-Centered Care, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Qualitative

INTRODUCTION

Parents have described the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) environment as a “wilderness of another world without any landmarks” (Hall, 2005, p.181). Contributing to this perception is that the work of sustaining lives of critically ill children requires the use of technology. Thus PICUs are often filled with constant noise from the multitude of alarms, monitors, and machinery. The PICU physical environment can be congested with life-saving equipment often minimizing the child patient in his or her hospital bed and leaving precious little free space at the bedside for parents or family members to participate. Since becoming a subspecialty in pediatric care in the 1960’s (Foglia and Milonovich, 2011), PICU policies in the United States often limit parent visitation thereby contributing to a culture that has minimized the importance and value of parental presence at the bedside and parental involvement in decision making (Kuo et al., 2012). Parents and clinicians in the United States have expressed differing views on restricting visitation to specific daytime hours, and at shift changeover, medical rounding, and resuscitation events (Baird et al., 2015; Uhl et al., 2013), with parents favoring less restriction and clinicians favoring more. However in other countries this has not been the case and over the past few decades there has been a renewed effort to engage in family-centered care (FCC) across pediatric units in the United States (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003, 2012; American Nurses Association, 2008, 2015). With the push for pediatric care to be family-centered, the PICU culture is slowly shifting to include parents in every aspect of their child’s care and to encourage partnerships between parents and members of the health care team. The aim of this study is to describe parent perceptions of FCC in the PICU, specifically how the PICU as a physical and cultural environment impacted parents of critically ill infants. Understanding the experience of parents of children in the PICU and their perception of family-centered care will inform this ongoing work and potentially lead to more effective implementation strategies.

BACKGROUND/SIGNIFICANCE

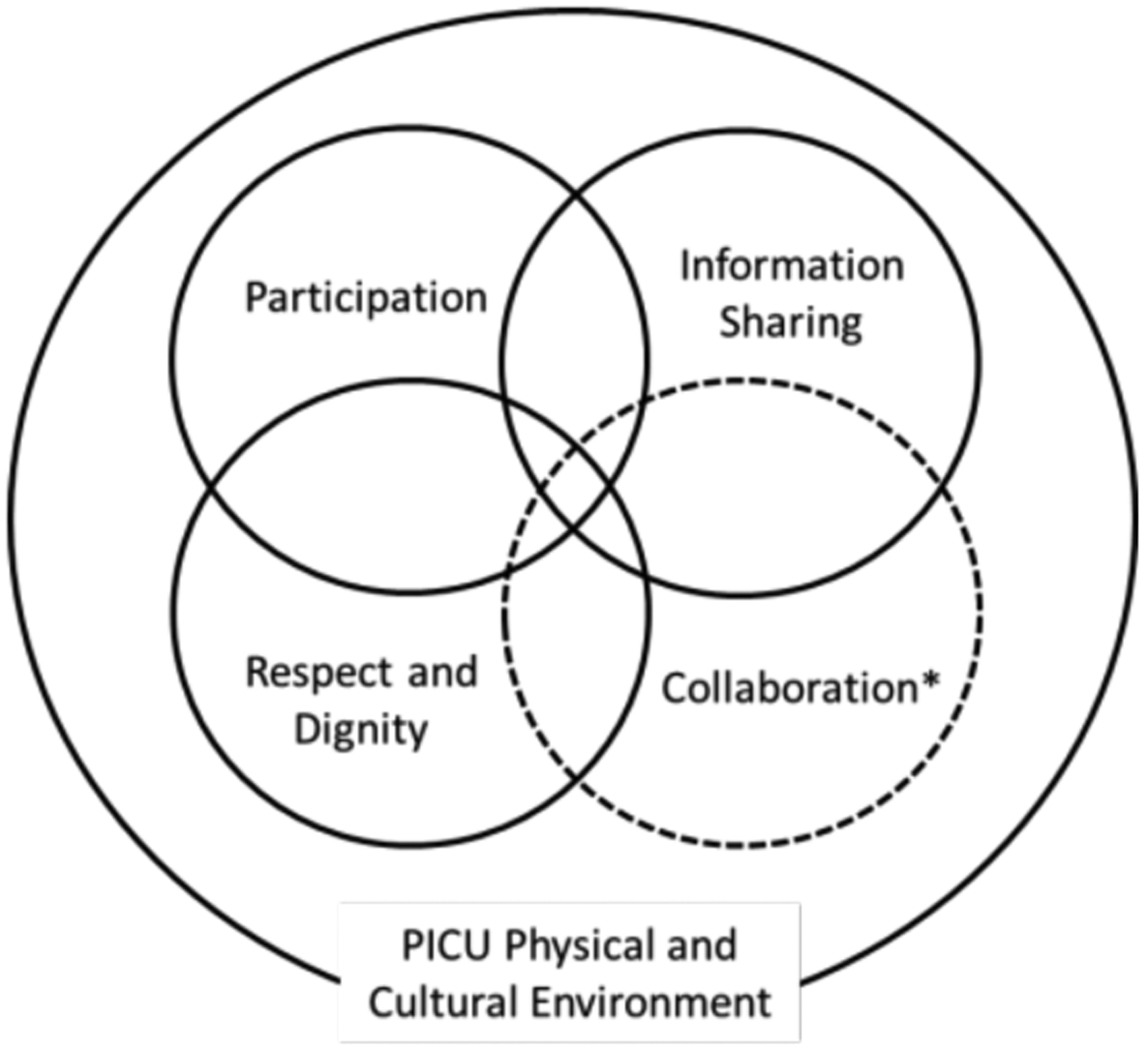

The Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) defines FCC as a partnership between families and health care professionals that contributes to better outcomes for patients and their family members, increased quality and safety, superior health care experiences, and enhanced satisfaction with care (www.ipfcc.org). According to the IPFCC, FCC includes four concepts: respect and dignity, information sharing, participation in care and decision making, and collaboration between patients, families, and the healthcare team (www.ipfcc.org). Multiple professional organizations have advocated for the delivery of pediatric health care in a manner that is patient and family-centered (The Institute of Medicine, 2001; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003, 2012; American Nurses Association, 2008, 2015).

In their grounded theory study examining the social and physical environments of the PICU, Butler et al. (2019) found that the environment impacted parent-provider relationships at end of life, but how does the PICU environment impact parent perception of the delivery of FCC? The importance of the physical environment (i.e., the makeup of the unit, patient room, and waiting room) in the enactment of respect and dignity, information sharing, and participation while in the PICU is understandable. However, to understand the impact of the cultural environment, or the shared attitudes, values, goals, and behavioral practices of the PICU, one must understand how care has been delivered historically. In the past, hospitalized children were cared for exclusively by staff with little involvement in care or decision making by parents; parental visitation was also severely restricted (Johnson, 1990; Jolley, 2007; Jolley and Shields, 2009). As care of the hospitalized child changed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, parents became more directly involved in care and decision making for hospitalized children. This necessitated family-centered partnerships with hospital staff, specifically nurses and physicians. While the care of children hospitalized in acute settings in the United States has made strides in the transition to a more family-centered model, PICUs have been slower to adopt this method of care delivery (Butler et al., 2013; Foglia and Milonovich, 2011), perhaps due to their use of technology, the critical conditions of their patients, and the history of limited visitation and participation by parents. Generally speaking, the PICU cultural environment can be characterized as having limited family visitation and/or involvement in direct care and decision making (Baird et al., 2015; Frazier et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2012). As a result of these constraints on the family, the PICU nurses were the child’s primary and often only direct caregiver. Parents have reported feeling that their infant “belonged to the staff” (Cantwell-Bartl and Tibballs, 2013) and have perceived nurses as both facilitators (Ames et al., 2011; Latour et al., 2011; Mattsson et al., 2014) and barriers (Ames et al., 2011; Carnevale et al., 2007; Macdonald et al., 2012) to parent participation in the child’s care.

Parents are integral members of the partnership that is needed to ensure the successful delivery of FCC in pediatric critical care settings. As such, their perspective on how well FCC is being implemented is critical. The evidence has shown that parents have both positive and negative perceptions of the implementation of FCC in the PICU. We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a longitudinal study of parent involvement in decision-making in an intensive care environment to further elaborate the role of the physical and cultural environment in parent perception of the delivery of FCC.

METHODS

This secondary analysis was based on interview data from a subsample of parents enrolled in a primary study that examined the trajectory of decision making for infants with complex life-threatening conditions (R01NR010548, P.I. Docherty). The third author of this manuscript was the PI for the primary study; the first, second, and fourth authors were primarily responsible for this secondary analysis and were not involved with the primary study. Institutional review board (IRB) approval (16–1439) was obtained from the first author’s academic institution as well as from the IRB responsible for oversight of the primary study. An overview of the primary study is presented below.

Primary Study

The primary study (R01NR010548, P.I. Docherty) from which the data for this secondary analysis was obtained took place in a major academic children’s hospital in the Southeastern United States. This PICU environment was one with few private rooms which were reserved for children requiring isolation. The majority of the infants were cared for in a large, open area that contained 6–8 bed spaces with retractable curtains present between each bed space for limited privacy. The unit allowed for visitation, however visitors were asked to leave during shift changeover, morning medical rounds, and emergent situations. Only those over the age of 12 were allowed to visit and one family member could stay overnight at bedside in a portable recliner. A waiting room was adjacent to this PICU and all visitors were required to request access from staff members when entering the unit. A longitudinal mixed-methods case-study design was used to examine the trajectory of parental decision making for infants with complex life-threatening conditions. Parent enrollment in the primary study was initiated at the birth of their infant (for infants whose condition was diagnosed prenatally) or within days of the diagnosis (for infants whose condition was diagnosed in the post-natal period). Subsequently, interview data, parent reported outcome data and infant clinical data were collected at least monthly for one year for those infants who lived, and at least monthly until death and at 6 and 12 months following death for those infants who did not survive. In addition to monthly data collection, the investigators collected data when a major treatment event or decision occurred; there were multiple instances for which the monthly and event/decision data collections coincided and were combined to minimize parent burden.

Secondary Analysis

Design.

In this secondary analysis, a qualitative descriptive design was used to examine parents’ experience with the core concepts of FCC and how the physical and cultural environment of the PICU influenced those experiences.

Sample Selection.

The primary study sample consisted of infants (n=30) diagnosed with three categories of conditions: complex congenital heart anomalies (n=10); extreme prematurity (n=9); metabolic conditions requiring stem cell transplantation (n=11). Since our study aims focused on the PICU environment, we used only data from parents of infants with complex congenital heart anomalies who were cared for in a PICU environment. The cases (defined as an index infant, the infant’s mother and the infant’s father) selected for this analysis were purposively sampled, with assistance from the primary study investigators. The cases were sampled sequentially, based upon the following criteria: (a) quantity and depth of information related to FCC contained in parent interview data; (b) informational variability based upon time of diagnosis (i.e., pre/post natal diagnosis); and (c) length of PICU stay. For example, the first case was purposively chosen based on primary study investigators’ perceptions of the quantity and information richness related to parenting an infant in the PICU. The second case was then chosen based upon the timing of diagnosis (post-natal versus prenatal) to determine any variability based on diagnosis timing. The third case was chosen based on a reduced medical complexity and a shortened length of PICU stay that was different from the two previously analyzed cases. Our sampling goal was to achieve what Hennink et al. (2017) have called “meaning saturation”, or the point at which themes or issues have been fully elaborated and “no further dimensions, nuances, or insights of issues can be found” (p. 594). The authors determined that saturation was achieved after completing the analysis of data from three cases (61 interviews, approximately 1500 pages of data). Each case contained an infant with a complex congenital heart anomaly and as a matter of chance, a married mother and father in their 30’s. The first case infant (C1) was a female of minority race/ethnicity with a prenatal diagnosis who spent approximately 150 days in the PICU. The second infant (C2) was a non-minority female with a post-natal diagnosis who spent approximately 300 days in the PICU, while the third infant (C3) was a non-minority male with a pre-natal diagnosis who was hospitalized in the PICU for just under a month.

Data Analysis.

Data analysis entailed careful reading of the interview transcripts for each case and development of codes that were applied to the entire data set. A data management program was used to support data coding and analysis (Atlas. Ti, Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany). Using directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) the first author coded the data using the FCC core concepts as defined by the IPFCC as the initial start list of codes. Following this initial round of coding, data related to each of the core concepts were reviewed to identify the nature of parents’ experiences related to each of the core concepts and the PICU physical and cultural environment. A working codebook was developed that included definitions and text examples of all FCC codes (Miles et al., 2014).

Trustworthiness.

Given the first authors’ clinical experience in a PICU and impressions regarding the implementation of FCC in that setting, analytic memos were routinely composed throughout data analysis to track her assumptions and biases, and as a means to preserve analytic insights (Saldana, 2013). The working codebook was reviewed and refined during data analysis with input from the second author, an expert in qualitative research. In the interest of supporting trustworthiness and to evaluate the reliability of the coding, the second author performed code checks on 20% of the interview transcripts. The first and second authors met frequently to discuss the application of codes and to resolve discrepancies in coding, if any.

FINDINGS

Our analysis revealed the IPFCC core concepts of information sharing, participation, respect and dignity in the data from three cases. Based on parents’ report, we describe how each core concept was manifested in the PICU. We also examine how the parents perceived the physical and cultural environment of the PICU as influencing implementation of FCC, and parenting in the PICU.

Information Sharing

Impact of the physical and cultural environment on information sharing.

Parents of infants in the PICU valued regular, in-depth information exchanges with members of the health care team that explained options for treatment, provided details regarding their infant’s condition and care plan, and was conveyed using language that parents understood. The parents in each case indicated that after admission to the PICU and prior to any surgical procedures, the infant’s clinicians communicated information using images of the infant’s anatomy to thoroughly explain diagnoses and recommended procedures. Parents indicated that “he brought it down to a level that we understood and wasn’t over our head” (C1) and that this type of information exchange “made it so black and white for me” (C1) and helped to allay parents’ initial experience of being overwhelmed by the amount and complex nature of information received. Additionally, when preparing parents for procedures such as placement of tracheostomy and/or nasogastric feeding tubes, parents described how nurses used dolls and booklets to show how each tube would look and how to care for it. Parents described the dolls as a non-threatening approach that helped them become comfortable with the appearance and care of these medical devices. Parents discussed how they felt comfortable asking questions about their infant’s care and gained valuable information from the nurses who were a constant presence at the infant’s bedside. One mother stated, “The nurses… will give me information and they kind of explain things and I’m sitting there and they’re doing things and we talk all day long” (C2).

Parent satisfaction with information sharing was diminished when, in situations of prognostic uncertainty, they perceived clinicians as purposefully vague about their infant’s prognosis or treatment. In two of the three cases, the infant’s medical condition was complicated by multiple setbacks and did not follow the course initially anticipated by the clinicians. Both sets of parents (C1, C2) indicated that when they asked physicians for more information, they were given “non-committal” answers to questions and vague date ranges for recovery or subsequent surgeries. Parents indicated decreased satisfaction with communication when this occurred and subsequently pushed physicians for more concrete information about their infant’s condition and treatment plan.

Each infant in this study had a complex congenital heart anomaly requiring life-saving intervention from multiple providers soon after birth. As the infants’ conditions and treatment courses evolved, the number and type of clinicians involved increased. Although parents were satisfied with how individual clinicians communicated with them, each parent reported that miscommunication between clinicians created conflict and parental mistrust. One mother commented that she felt clinicians were “passing the buck” (C1) by suggesting that another clinician was responsible for critical decisions; she reported that no one was willing to take the lead and oversee her daughter’s care.

As PICU stays lengthened and their infant’s condition evolved, parents experienced the team as no longer giving specific timelines for recovery and also as modifying and broadening treatment goals. Two parent dyads reported being frustrated by this; one of these fathers indicated that this vagueness was so the PICU team could “cover their asses” (C2) in case of a negative outcome. One mother described resigning herself to this approach to communication saying, “That’s just how it works here” (C1) indicating her perception of the culture in the PICU. One father stated that vague goals and timelines benefitted his infant by allowing her to progress at her own pace without pressure. All parents expressed that the frequent changes in the plan of care were both overwhelming and difficult to understand.

Participation

Impact of the physical and cultural environment on participation.

The impact of the physical and cultural environment on parent participation was evident in the data. Parents wanted to actively participate in their infant’s care, and were initially involved in performing basic parenting tasks such as holding the infant, changing diapers and bathing. Over time, participation progressed to include more complex aspects of parenting such as involvement in treatment decision making and care planning. Parents experienced this as being included as part of the team and their input being valued by clinicians; one mother stated, “My vote really counts” (C1). Parents of each of the three infants reported they were comfortable participating in bedside medical rounds, which provided an opportunity to exchange information with the care team.

All parents perceived the nurses as gatekeepers to participation in the basic aspects of their infant’s care. One mother stated, “It depends on the nurse working as to how involved I can be with daily cares” (C2), and another stated,

It would be really nice if the nurse decides you can play a part in your baby’s care, ‘cause if I would’ve known that day one I think it would’ve been a tremendous relief and I don’t think I would’ve been as sad.

(C1)

Two of the mothers (C1, C3) expressed feelings of not being a mother to their infants because of the abnormal circumstances in the immediate post-natal period and perceived barriers to participating in their infant’s care posed by the PICU staff and environment. In the first weeks of life, each infant was attached to multiple machines with varying numbers of tubes and lines snaking around the bedside; parents reported having to be taught how to safely perform basic parenting tasks made more difficult because of the equipment and tubes connected to their infant. Parents commented that their participation was also impacted by the nurse and respiratory therapist assigned to their infant on a given shift. Parents had definite preferences regarding staff but little control over staff assignments. One mother indicated her stress level varied based on how “on top of things” (C2) she needed to be, based on which nurse and respiratory therapist were on duty.

Parents in this study reported participation in medical rounds, yet the specific nature of their participation was based on unit policy. Parents indicated that they were not “allowed” (C2) on morning rounds in which the entire interdisciplinary team was present, but could participate in afternoon rounds which involved only the medical team; they had not been given an explicit explanation for this distinction. Although parents reported modifying their visitation schedule to participate in afternoon rounds they nonetheless would have appreciated the option of participating in the rounds that best suited their schedules.

Parent participation was also impacted by unit policies when there were emergencies or cardiac arrests (codes) affecting children in the PICU. Parents indicated that they were “kicked out” (C2) of the unit during codes and often not permitted to return for many hours. One mother reported that she unintentionally witnessed emergencies and code events for other children. According to unit policy, she should have left during this time but was holding her infant who was attached to an array of equipment and would have required the assistance of multiple nurses to return the infant to bed. This mother reported that witnessing the code was “scary” because although the curtains were pulled during the emergency, “you could still hear everything” (C2). Parents reported barriers to spending the night with their infant, indicating there were no actual bed spaces for overnight visitation and limited room at the bedside for the reclining chairs that were provided.

Respect and Dignity

Impact of the physical and cultural environment on respect and dignity.

Parents had individual impressions of the physical and cultural environment of the PICU and how this impacted the way they were treated. Parents frequently referred to the “way things work” (C1) in the PICU. For example, parents discussed the hierarchy of power in the PICU (as they perceived it to be) and how this influenced who they believed could implement their requests. One mother stated, “The nurse practitioners I try and get to change things ‘cause they seem to kind of have more power”(C2). Another mother believed that her understanding of what goes on in the PICU stemmed from being there when doctors “drop by” and listening to the nurses “talk to each other” (C1).

Parents noted how support from the health care team conveyed respect and dignity. Parents were positively affected by what they viewed as clinicians’ investment in their infant’s care and survival; they identified instances when nurses showed genuine excitement or disappointment related to changes of their infant’s illness trajectory; a mother commented that the nurses were her infant’s “cheerleaders” (C1). One mother was moved when she was told that nurses had called or visited on their days off to check on her infant after a surgery, and another mother was deeply moved when nurses came in from home to support her when her daughter died in the PICU. Parents frequently talked of the rapport with their nurses; the parents whose infants experienced prolonged PICU stays developed relationships with staff that they described as feeling more like “friends than nurse and parent”(C1, C2). Likewise, a mother whose infant spent minimal time in the PICU commented on her experience,

I will say everybody in the unit was almost um… so respectful to the primary parents, I mean just really… I mean they make you feel special as the parents and make you feel, I mean I really feel like they go out of their way to sort of bring you into the fold.

(C3)

Parents also indicated that staff displayed respect for their spiritual needs by praying with them while their infant was in the PICU.

On the other hand, parents also reported behavior that they experienced as not conveying respect and dignity. Parents of one infant perceived that members of the health care team had “given up” (C2) on their infant when the physicians mentioned withdrawal of intensive care as opposed to more treatment options; they indicated this was a source of distress and contributed to a sense of distrust and conflict with this physician.

Another environmental factor that parents perceived as impacting dignified and respectful care in the PICU was the lack of consistency in those providing care to their infant. Parents commented on the frequency with which the nurses responsible for their infant’s care had little, if any, experience caring for an infant in the PICU. This lack of consistent providers with PICU experience was especially disturbing to parents in one prolonged-stay family. For example, this mother stated,

Maybe people should just be able to stay in little homes where they know their people and stuff and place and…I know why floats have to happen, and stuff like that but just seems like…you’re taking people out of their comfort zone putting them in a place where they’re not quite sure and in those situations…it seems like it’s a little more critical to have those people in place.

(C2)

This parent dyad eventually requested that a consistent core group of nurses be assigned to care for their daughter.

As previously mentioned, one of the parent dyads in this study experienced trust issues with an attending physician; these trust issues developed into more pervasive conflicts with other health care team members. They perceived this physician as not respecting their care preferences and questioned whether the physician might engage in care that would harm their daughter. Given their understanding of the power hierarchy in the PICU and the institution overall, the parents of C2 expressed concerns that there weren’t “checks and balances” in place for disagreements between parents and attending physicians. This particular mother stated:

There needs to be more accountability at that level…If I have a problem with the nurse I go to the charge nurse. If I have a problem with the charge nurse I’ll go to the NP, fellow, whoever like if I have a problem with them I go to the attending. Well what if I have a problem with the attending?

(C2)

Since these parents perceived that no one was responsible for oversight of attending physicians, they were concerned for their infant’s safety when this particular physician was on duty.

DISCUSSION

A research study investigating FCC practices once asked the question “an office or a bedroom?” when referring to the PICU environment (Macdonald et al., 2012). These authors found that FCC as theorized and operationalized as policy differed from actual parent experiences in the PICU. The parents in our study described multiple environmental factors that played a role in their perception of FCC in the PICU, indicating that the physical and cultural environment of the PICU exerts contextual influence in the delivery of care that encompasses the concepts of information sharing, participation, and respect and dignity. We found no evidence of collaboration that reflected our operationalization of the IPFCC definition as involvement in programmatic and policy level collaboration. We did find evidence of collaboration between parents and clinicians related to care coordination, treatment plans, and delivery of care. Given the primary study’s aims, participants were not asked about their involvement in programmatic and policy level collaboration and collaboration as defined for this study was unlikely to be in our data. Accordingly, we cannot definitively refute the inclusion of collaboration in the PICU FCC conceptual model.

Information Sharing

Infants cared for in the PICU can have unstable medical conditions and as such their plan of care can change quickly and without notice; this unpredictability was a source of uncertainty and thus stress for parents in this study. In her work with parents of hospitalized children, Mishel (1988) discussed uncertainty as a major variable in how parents perceived their child’s illness and thus their ability to incorporate information was largely impacted by their uncertainty. The situation this creates for parents and clinicians alike is both difficult and unavoidable given the critical, complex and sometimes rare nature of the illnesses faced by infants and children hospitalized in the PICU, compounded by the unfamiliar environment. Parents expressed that their satisfaction with information sharing and communication was decreased when they perceived clinicians as giving vague or broad answers to parental questions, however because of the tenuous and unpredictable nature of pediatric critical care, clinicians might be unable to give information that will be perceived as anything but vague.

The possibility exists that more frequent exchange of information in the form of participation in family meetings or conferences and daily bedside medical rounds could help to lessen or at least normalize and convey sensitivity to parent uncertainty and in turn, distress related to changes in their child’s plan of care. Research on family conferences in the PICU indicates that parent satisfaction with communication increased when providers considered competing demands on parent schedules (Levin et al., 2015), and discussed medical and treatment information in understandable language (Michelson et al., 2017), and in a patient and family-centered, empathetic manner (October et al., 2016). In our study, two of the dyads indicated that family meetings were commonplace to discuss their infant’s condition and treatment plan; these families had infants with prolonged stays where the plan of care changed frequently. Additionally, if PICU clinicians are hesitant to set specific treatment goals and timelines for a child because of their ever-changing condition, sensitive communication with parents that acknowledges the resultant uncertainty and impacts on parental stress could improve parent perception of information sharing. As a result, clinician sensitivity to and acknowledgement of parental uncertainty may have implications for the development of interventions that support information exchange with parents in the PICU who are dealing with uncertainty related to their child’s illness and treatment plan. Additionally, development of strategies for information exchange that ensures parents both understand and are satisfied with the nature and specificity of information provided by clinicians could aid in reducing the information uncertainty experienced by parents in the PICU. Parents of children in the PICU have indicated that “keeping them informed” and “being honest” were important clinician strategies to support parent’s while in the PICU (October et al., 2014). DeLemos et al. (2010) found that parents in the PICU were better able to build trusting relationships with their child’s providers when the parents perceived communication to be honest, inclusive, compassionate, clear, comprehensive, and coordinated. In Mishel’s uncertainty in illness theory, the ability to establish trusting relationships with clinicians caring for a loved one led to a lower level of overall uncertainty (Mishel, 1988).

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends bedside medical rounds that are inclusive of family members as a pediatric inpatient practice standard (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012). All parents in this study indicated that while they were not allowed to participate in morning interdisciplinary bedside rounds, they did attend afternoon bedside rounds as a means to exchange information and participate in their child’s care. While no parent spoke of policies that prohibited their participation in morning rounds, two parent dyads frequently said they “weren’t allowed on morning rounds” without further elaboration if this was an explicit unit policy stated to parents upon admission or one that was implicit in the PICU culture. Baird et al. (2015) found that both explicit and implicit unit-based rules impacted parents of children in the PICU. Additionally, the intersection of nurse and parent perceptions of unit-based rules impacted the delivery of family-centered care.

Participation

Early in our study, we found that all parents commented that nurses both facilitated and inhibited parental involvement in their infant’s physical care; this belief is echoed in the literature regarding parent participation in the PICU (Ames et al., 2011; Cantwell-Bartl and Tibballs, 2013; Geoghegan et al, 2016). As their participation increased, parents began to view themselves as experts in the care of their infant. Studies of parents whose infants had prolonged hospitalizations reported that parents began their infant’s stay in the PICU naïve, but over time came to better understand the unit and its culture. For example, Geoghegan et al. (2016) found that parents either developed strong relationships with the staff and came to know the culture of the unit, or became increasingly stressed over time and their “needs and concerns escalated”. This finding was true for our prolonged-stay parents as well in that one of the two parent dyads formed a highly functional working relationship with the health care team while the other dyad developed an active distrust of the clinicians and experienced multiple conflicts related to their infant’s care. Nurses in the Geoghegan et al. (2016) study also believed that prolonged stay parents became “institutionalized” to the PICU, meaning they develop an understanding of the environment and inner workings (or culture) of the PICU. This too was observed in our study in part when parents routinely used previously unknown medical terminology when discussing their infant’s condition and their observations of the PICU environment.

Respect and Dignity

The parents in our study expressed that having consistent nurses for their infant was important to them. Parents indicated that they preferred nurses who had previously cared for their infant; one parent dyad specifically requested that a core group of such nurses be assigned. As a sign of respect for parent wishes, every attempt should be made to establish a core group of consistent nurses for each child in the PICU. Parents whose infants had prolonged stays were especially impacted by the continuity of care given the complicated nature of their infant’s condition and treatment course. Parents evaluated care quality based on how well nurses knew their infant and the infant’s unique characteristics. As reported in Baird et al. (2016), parents preferred having consistent nurses and expressed relief when this occurred; parents experienced frustration when faced with frequent new caregivers and felt it necessary to remain vigilant at the bedside. Parents in the Geoghegan et al. (2016) study also expressed that finding out which nurse would be caring for their child would either produce the sentiment “Oh thank goodness” or “Oh, my God, this is going to be a hell of…” (p. e499). Perhaps one barrier to the implementation of consistent caregivers in the PICU is the nurses themselves. Nurses have indicated that they would prefer not to work with the same patients for multiple shifts because it could create boredom or possible attachment to a patient/family (Butler et al., 2015); many PICU nurses indicated that caring for the same patient repeatedly would not allow them to advance their knowledge or skills (Baird et al., 2016). In addition to respecting parent preferences for care of their infant and increasing satisfaction, neonatal intensive care unit outcomes research has shown that length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation may be positively impacted by consistent nurse assignments (Mefford and Alligood, 2011).

LIMITATIONS

As mentioned previously, because of the secondary nature of this data, we were unable to control the course of each interview and probe further on some of the data related to our study aims (e.g., institution-wide programmatic and policy collaboration). The primary study investigators were involved in selection of cases for this analysis, as such one might conclude this introduces the possibility of selection bias and is therefore a limitation; however we posit that our purposeful sample benefitted from the expertise and knowledge of the primary investigators. The small sample size of 3 cases could also be identified as a limitation, however we believe that the richness and amount of data analyzed mitigates this as a limitation. Further, the study participants were all cared for in the same institution and same PICU where the culture, management, and inherent policies may not reflect those at other institutions and PICUs. However, this data set was well suited to our study aims and the amount and longitudinal nature of our data allowed for analysis over time that revealed how parents of infants with prolonged PICU stays perceptions of the environment changed over time. The rigorous data analysis and coding checks also aided trustworthiness.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Continued research is necessary to ensure that the care delivered to patients and families in the PICU is family-centered and encompasses all core concepts. Parents of children in the PICU have indicated their dissatisfaction with communication and information sharing, focusing mainly on the uncertainty of their child’s prognosis and the resultant vague and changing treatment plan. Acknowledgement by clinicians of the unpredictability of a child’s PICU trajectory as a source of stress for parents is needed. Further, interventions to support consistent, regular communication and improve parent satisfaction with information sharing are needed. Additionally, parents of children with a prolonged PICU stay have indicated their preference of having a consistent set of nurses care for their children. Research should be performed to explicate the barriers, both environmental and cultural, that have prevented the assignment of consistent nurse caregivers from becoming a reality in the PICU. Moreover, while this study focused specifically on FCC in the PICU, the results found herein are not necessarily unique to the PICU and could be generalizable to other pediatric care environments where children with life-threatening conditions receive care supported by technology.

CONCLUSIONS

Parents of infants hospitalized in the PICU endure considerable stress as a result of their infant’s critical illness; the environment of the PICU has been shown to both contribute to and alleviate parental distress. Parents expect that they will be able to participate in the care of their infant, have open, honest and compassionate information exchange on a regular basis via family meetings and rounds, and that their wishes for consistent nurses will be respected. The physical and cultural environment of the PICU should be considered when attempting to deliver quality intensive care that is both patient- and family-centered as outlined by the IPFCC.

Figure 1:

Conceptualization of FCC in the PICU. *Collaboration is tentatively present pending further investigation and development.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE.

The physical and cultural environment of the PICU can both alleviate and add to parent distress.

Parents of infants in the PICU encounter uncertainty and added stress due to the fragile nature of their infant’s condition. Frequent and honest communication from clinicians that acknowledges this uncertainty is important to support parents.

Parents of infants with extended PICU stays seek consistency in those caring for their infants. Establishing consistent nurse caregivers in the PICU is important to maintain a sense of stability for the patient and parents.

FUNDING SOURCE

The first author acknowledges training support from T32NR007091, awarded to The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing by the National Institute of Nursing Research. This work was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2003). Family pediatrics: Report of the task force on the family. Pediatrics, 111, 1541–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Patient and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics, 129, 394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association & Society of Pediatric Nurses. (2008). Pediatric Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association, National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, & Society of Pediatric Nurses. (2015). Pediatric Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, 2nd edition Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Ames K, Rennick. J, & Baillargeon S (2011). A qualitative interpretive study exploring parents’ perception of the parental role in the paediatric intensive care unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 27, 143–150. Doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird J, Davies B, Hinds P, Baggott C, & Rehm R (2015). What impact do hospital and unit-based rules have upon patient and family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit? Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30, 133–142. Doi: 1031016/j.pedn.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird J, Rehm R, Hinds P, Baggott C, & Davies B (2016). Do you know my child? Continuity of nursing care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Nursing Research, 65, 142–150.Doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Copnell B, & Hall. H (2019). The impact of the social and physical environments on paren-healthcare provider relationships when a child dies in PICU: Findings from a grounded theory study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. Doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Copnell B, & Willetts G (2013). Family-centred care in the paediatric intensive care unit: an integrative review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23, 2086–2100. Doi: 10.1111/jocn.12498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Willetts G, & Copnell B (2015). Nurses’ perceptions of working with families in the paediatric intensive care unit. British Association of Critical Care Nurses, 22, 195–202. Doi: 10.1111/nicc.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell-Bartl A, & Tibballs J (2013). Psychosocial experiences of parents of infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome in the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 14, 869–875. Doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829b1a88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale F, Canoui P, Cremer R, Farrell C, Doussau A, Seguin M,…. (2007). Parental involvement in treatment decisions regarding their critically ill child: a comparative study of France and Quebec. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 8, 337–342. Doi: 10.1097/01.PCC0000269399.47060.6D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLemos D, Chen M, Romer A, Brydon K, Dastner K, Anthony B,… (2010). Building trust through communication in the intensive care unit: HICCC. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 11, 378–384. Doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b8088b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foglia D, & Milonovich L (2011). The evolution of pediatric critical care nursing: past, present, and future. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 23, 239–253. Doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier A, Frazier H, & Warren N (2010). A discussion of family-centered care within the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 33, 82–86. Doi: 10.1097/cnq.0b013e3181c8e015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan S, Oulton K, Bull C, Brierley J, Peters M, & Wray J (2016). The experience of long-stay parents in the ICU: a qualitative study of parent and staff perspectives. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 17, e496–e501. Doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E (2005). Being in an alien world: Danish parents’ lived experiences when a newborn or small child is critically ill. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 19, 179–185. Doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00352.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink M, Kaiser B, & Marconi V (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27, 591–608. Doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, & Shannon S (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. Doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. (2017). Retrieved May 20, 2017 from www.ipfcc.org

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B (1990). The changing role of families in health care. Children’s Health Care, 19, 234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley J (2007). Separation and psychological trauma: a paradox examined. Paediatric Nursing, 19, 22–25. Doi: 10.7748/paed.19.3.22.s22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley J, & Shields L (2009). The evolution of family-centered care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24, 164–170. Doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo D, Houtrow A, Arango P, Kuhlthau K, Simmons J, & Neff J (2012). Family-centered care: current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Maternal Child Health Journal, 16, 297–305. Doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0751-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour J, Van Goudoever J, Schuurman B, Albers M, Van Dam N, Dullaart E,…. (2011). A qualitative study exploring the experiences of parents of children admitted to seven Dutch pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Medicine, 37, 319–325. Doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2074-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin A, Fisher K, Cato K, Zurca A, & October T (2015). An evaluation of family-centered rounds in the PICU: room for improvement suggested by families and providers. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 16, 801–807. Doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald M, Liben S, Carnevale F, & Cohen S (2012). An office or a bedroom? Challenges for family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Child Health Care, 16, 237–249. Doi: 10.1177/1367493511430678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson J, Arman M, Castren M, & Forsner M (2014). Meaning of caring in pediatric intensive care unit from the perspective of parents: a qualitative study. Journal of Child Health Care, 18, 336–345. Doi: 10.1177/1367493513496667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefford L, & Alligood M (2011). Evaluating nurse staffing patterns and neonatal intensive care unit outcomes using Levine’s conservation model of nursing. Journal of Nursing Management, 19, 998–1011.Doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson K, Clayman M, Ryan C, Emanuel L, & Frader J (2017). Communication during pediatric intensive care unit family conferences: a pilot study of content, communication, and parent perceptions. Health Communication, 32, 1225–1232. Doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1217450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman A, & Saldana J (2014). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mishel M (1983). Parents’ perception of uncertainty concerning their hospitalized child. Nursing Research, 32, 324–330. Doi: 10.1097/00006199-198311000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel M (1988). Uncertainty in illness. IMAGE: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 20, 225–232. Doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- October T, Fisher K, Feudtner C, & Hinds P (2014). The parent perspective: “being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 15, 291–298. Doi: 10.1097/PCC.000000000000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- October T, Hinds P, Wang J, Dizon Z, Cheng Y, & Roter D (2016). Parent satisfaction with communication is associated with physician’s patient-centered communication patterns during family conferences. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 17, 490–497. Doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl T, Fisher K, Docherty S, & Brandon D (2013). Insights into patient and family-centered care through the hospital experiences of parents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 42, 121–131. Doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]