Abstract

Background

In 2015, a large outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection occurred following a single patient exposure in an emergency room at the Samsung Medical Center, a tertiary-care hospital in Seoul, South Korea. We aimed to investigate the epidemiology of MERS-CoV outbreak in our hospital.

Methods

We identified all patients and health-care workers who had been in the emergency room with the index case between May 27 and May 29, 2015. Patients were categorised on the basis of their exposure in the emergency room: in the same zone as the index case (group A), in different zones except for overlap at the registration area or the radiology suite (group B), and in different zones (group C). We documented cases of MERS-CoV infection, confirmed by real-time PCR testing of sputum samples. We analysed attack rates, incubation periods of the virus, and risk factors for transmission.

Findings

675 patients and 218 health-care workers were identified as contacts. MERS-CoV infection was confirmed in 82 individuals (33 patients, eight health-care workers, and 41 visitors). The attack rate was highest in group A (20% [23/117] vs 5% [3/58] in group B vs 1% [4/500] in group C; p<0·0001), and was 2% (5/218) in health-care workers. After excluding nine cases (because of inability to determine the date of symptom onset in six cases and lack of data from three visitors), the median incubation period was 7 days (range 2–17, IQR 5–10). The median incubation period was significantly shorter in group A than in group C (5 days [IQR 4–8] vs 11 days [6–12]; p<0·0001). There were no confirmed cases in patients and visitors who visited the emergency room on May 29 and who were exposed only to potentially contaminated environment without direct contact with the index case. The main risk factor for transmission of MERS-CoV was the location of exposure.

Interpretation

Our results showed increased transmission potential of MERS-CoV from a single patient in an overcrowded emergency room and provide compelling evidence that health-care facilities worldwide need to be prepared for emerging infectious diseases.

Funding

None.

Introduction

Since the first identification of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in 2012,1 most patients infected with the virus have been exposed in the Middle East. As of March 23, 2016, 1698 laboratory-confirmed cases have been reported to WHO.2 On the basis of previous epidemiological findings,3 the potential of MERS-CoV to spread to large numbers of people has been considered low, by contrast with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). The basic reproductive number of MERS-CoV was estimated to be less than 1·0, suggesting low transmissibility.4, 5 However, a 2013 outbreak of MERS-CoV infection in Al Hasa, Saudi Arabia, where one patient infected seven other patients in dialysis and intensive care units,6 raised concerns about potential so-called super-spreaders7 that were reported during the SARS epidemic.8, 9

From May to July, 2015, a large outbreak of MERS-CoV infection occurred in South Korea from a traveller returning from the Middle East, which led to 186 confirmed cases (Patient 1 to Patient 186) in the country.10 Patient 1 was diagnosed at our hospital (Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea) after transmitting the virus at several health-care facilities before he came to our hospital. Patient 14 was exposed to Patient 1 outside the hospital and sought additional care at our hospital without knowing he was infected with MERS-CoV. Therefore, we experienced both South Korea's first MERS-CoV case and the case of highest transmission of MERS-CoV following a single patient exposure in an emergency room. We aimed to investigate the epidemiology of MERS-CoV infection in a crowded emergency room outside of the Middle East and the presence of multiple super-spreaders.

Methods

Contact investigation and management

In May, 2015, two patients with MERS-CoV infection (Patient 1 and Patient 14) sought care in our emergency room at the Samsung Medical Center without knowing they were infected with MERS-CoV. While these patients were in the emergency room, a large number of patients, visitors, and health-care workers were exposed during both events.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Little information on nosocomial outbreaks caused by Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outside the Middle East had been available before the large MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea in 2015, for which global alert was issued. We searched PubMed for reports published in English from May 1, 2015, to Dec 31, 2015, using the terms “MERS-CoV” and “Korea”. We identified 38 reports, none of which provided detailed description for the contact investigation of massive transmission of MERS-CoV from a super-spreader in an overcrowded emergency room setting.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this study is the first to categorise exposed patients into groups according to the type of exposure and to document group-specific incubation periods and attack rates. Furthermore, this study provides detailed epidemiological data, including a floor plan of the emergency room, to understand how MERS-CoV spread by a single super-spreader through several modes of transmission.

Implications of all the available evidence

Results from our contact investigation showed increased transmission potential of MERS-CoV from a single spreader, as has been documented in the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. The potential for similar outbreaks anywhere in the world should be noted, as long as MERS-CoV transmission continues in the Middle East. Our study provides evidence that hospitals, laboratories, and governmental agencies should be prepared for MERS-CoV infection.

When MERS-CoV infection was suspected in Patient 1 and Patient 14, contact investigation was immediately initiated. Since no one developed MERS among contacts who were exposed to Patient 1, only contacts of Patient 14 are reported here. We identified, from electronic medical record review and security video footage, all patients who had been in the emergency room with Patient 14 as contacts, regardless of the location and duration of exposure. We categorised patient contacts into three groups on the basis of their maximum exposure: patients who were in the same zone in the emergency room (group A; considered close contacts), those who were in different zones but had time overlap with Patient 14 in the registration area or radiology suite (30 min before and 2 h after; group B), and those who were in different zones (group C). Patients who were admitted to hospital for treatment of their primary illness after exposure in the emergency room were quarantined in private rooms for 14 days from the last exposure or discharged home after treatment was finished and continued isolation at home. Patients and their family members who were already discharged home were reached by telephone, informed about possible MERS-CoV exposure, and provided with hotline numbers for any inquiries.

Health-care workers who were exposed were identified through interviews and review of employees' duty schedules, electronic signature on medical records of Patient 14 and patient contacts, security video footage, and self-report. Health-care workers who provided direct care to Patient 14 were initially considered close contacts and were placed into quarantine at home for 14 days from the last day of exposure. Other health-care workers who worked in the emergency room during the same time period continued to work with monitoring and were removed immediately from duty if symptoms developed.

Demographic and epidemiological data

A confirmed case was defined as a person with laboratory confirmation of MERS-CoV infection from sputum samples, initially by real-time RT-PCR testing with amplification targeting the upstream E region (upE) and then confirmed by subsequent amplification of open reading frame 1a (ORF1a) using PowerChek MERS real-time PCR kits (Kogene Biotech, Seoul, Korea). Patients' demographic information, underlying disease, dates of emergency room visit, duration of stay with exact arrival and departure times, and location within the emergency room were collected. If radiographic examinations were done, the time of examination was collected. For health-care workers, age, sex, occupation, history of patient assignments and working or visiting zone, and dates and time of duty or emergency room visits were collected. The attack rate was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed cases by the total number of exposed individuals in the emergency room in each group. Because the total list of visitors was unavailable, we estimated the number of visitors who were in the emergency room by assuming that one patient had at least one visitor during their stay; we also simulated the scenarios of two and four visitors per patient. To avoid underestimation, we chose the assumption of one visitor per patient, which would give the highest attack rate among the scenarios. The incubation period was defined as the time of first exposure to the onset of clinical symptoms of MERS-CoV infections.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented with frequency (percentage) and continuous variables were summarised with median (range, IQR). We calculated overall comparison of attack rates across the groups with χ2 test and across zones with Fisher's exact test. Incubation period and exposure time were compared among groups with Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Tukey's test using ranks for multiple comparisons. To assess the risk factors for MERS-CoV infection among all patient contacts, we did a multiple logistic regression analysis based on likelihood ratio, by regressing on age, sex, underlying disease, and groups. In a subgroup analysis of patients in group A, the length of stay in the same zone and location were included. For these analyses, odds ratios and 95% CIs were reported. p values and 95% CIs were adjusted with Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons if necessary. Two-sided p values of less than 0·05 were considered significant. We used SAS version 9.4 and GraphPad Prism version 6.04 for statistical analyses.

Hospital and environmental conditions

Samsung Medical Center is a modern 1982-bed university-affiliated tertiary hospital providing referral care in South Korea (total population roughly 50 million), with roughly 9000 staff, including more than 1400 physicians and 2600 nurses.

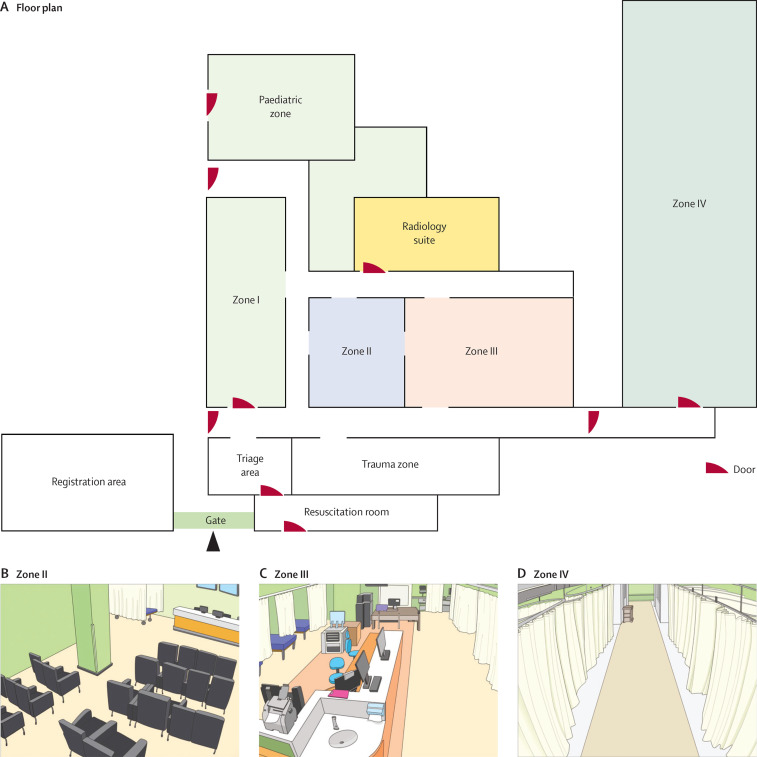

The emergency room entrance is located on the ground floor near the south gate of the main hospital building. More than 200 patients are seen in the emergency room each day; the average duration of stay in the emergency room was 15 h before the MERS-CoV outbreak (see appendix p 2 for details on emergency room overcrowding index). The emergency room has seven patient care areas, including zones I to IV for adults, a trauma zone, a resuscitation room, and a paediatric zone (figure 1 ). The paediatric zone and zone IV are separated from the rest of the main areas. Two negative-pressure rooms are located in the paediatric zone and two are in zone IV. The emergency room has its own radiology suite for emergency room patients only. The sizes of each zone were as follows: zone I 121·7 m2, zone II 64·2 m2, zone III 168·3 m2, and zone IV 223·9 m2. Zones I and II included seating areas (50 chairs in zone I and 26 chairs in zone II), where stable patients received treatment and waited for test results. Seriously ill patients, who required close observation and needed a designated bed, were moved to zone III (17 beds) or zone IV (23 beds). Zone IV was used for patients being admitted. Beds in zones III and IV were spaced roughly 1·8 m apart, with curtains in between. Nurses were assigned to work in designated zones, whereas physicians and transfer agents took care of patients in several zones. All zones in the emergency room were covered by the same air handling units.

Figure 1.

(A) Floor plan of the emergency room and schematic views of (B) zone II, (C) zone III, and (D) zone IV

Patient 14 was cared for in zones II–IV between May 27 and May 29, 2015.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

On May 20, 2015, South Korea's first case of MERS was diagnosed in a 68-year-old man (Patient 1) in Samsung Medical Center (appendix p 3). Although he denied travel history to Saudi Arabia, he had actually travelled to Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar between April 18 and May 3. On May 11, he developed fever and cough, and visited three health-care facilities from May 12 to May 17. He visited the emergency room at Samsung Medical Center on both May 17 and May 18 because of increasing symptoms. He stayed in zone II for 4 h on May 17 and in zone I for 5 h on May 18 before placement into isolation. 285 patients and 193 health-care workers were exposed to Patient 1, but no transmission occurred in our hospital. However, it was later found that Patient 1 transmitted MERS-CoV to 28 individuals in health-care facilities he had visited before coming to our hospital.10 Patient 14 was one of the patients who contracted MERS-CoV from Patient 1 at another hospital and subsequently sought care in our emergency room without knowing about MERS-CoV exposure.

The 14th patient with confirmed MERS in South Korea (Patient 14) was a 35-year-old man who was initially treated for community-acquired pneumonia at another hospital where Patient 1 had also been admitted. From May 15 to May 17, Patient 14 stayed in the same ward with Patient 1. Patient 14 was discharged from the first hospital with improvement on May 20 after antibiotic treatment. On May 21, he was readmitted to the first hospital because of fever and was cared for 5 days until May 25, when he moved to another hospital (second hospital) because of deteriorating respiratory symptoms. Eventually, he left the second hospital and came to the emergency room at Samsung Medical Center on May 27. He had not yet received notification about his exposure to MERS-CoV during his previous stay in the first hospital.

Upon arrival at our emergency room, he denied having travel history to the Middle East and any possible exposure to people infected with MERS-CoV. He was treated for possible bacterial pneumonia on the basis of partial improvement from previous antibiotic treatment and increased C-reactive protein concentration of 13·0 mg/dL (normal <0·3 mg/dL; appendix p 4). During his stay in the emergency room, he was provided with a mask but frequently could not hold it because of severe respiratory symptoms. He was not isolated in a separate room; a negative-pressure room was not considered at that time. As his dyspnoea aggravated on May 28, supplemental oxygen was administered at 2 L per min via a nasal cannula (up to 5 L per min). However, no aerosol-producing procedures, including nebuliser treatments, were given. On the night of May 29, he received a notification call from the health authorities about possible exposure to Patient 1, notified our hospital, and was immediately transferred from the emergency room to isolation in a negative-pressure isolation room. MERS-CoV infection was confirmed on May 30, and he was transferred to the nationally designated health-care facility. From May 27 to May 29, he stayed in three zones in our emergency room: zone II for roughly 10 h on May 27, zone III for 19 h from May 27 to May 28, and zone IV for 25 h from May 28 to May 29 (figure 1). Additionally, from May 27 to May 29, he went to the radiology suites four times. On May 27, he walked around and outside the emergency room and went to the toilet several times because of diarrhoea.

Between May 27 and May 29, 2015, the average ventilation rate in the emergency room was maintained at three air changes per h, taking 2 h to remove airborne contaminant with a 99·9% efficiency.11 The median temperature was 23·8°C (range 14·4–32·2), and the median relative humidity was 32·9% (range 27·1–36·8).

675 patients (117 in group A, 58 in group B, and 500 in group C), an estimated 683 visitors, and 218 health-care workers were identified as contacts of Patient 14 (table 1 ). We assumed that each patient had one visitor and added eight extra visitors (five to group A and three to group C) because two or more visitors were confirmed with MERS-CoV infection per patient. From May 30 to June 23, 82 cases (33 [40%] patients, 41 [50%] visitors, and eight [10%] health-care workers) of MERS-CoV infection were confirmed after exposure between May 27 and May 29. Demographic and epidemiological data of all contacts and individuals with confirmed MERS-CoV infection are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and epidemiological data of all contacts and confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection

|

All contacts (n=1576) |

Individuals with confirmed MESR-CoV infection (n=82) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n=675) | Visitors (estimated n=683) | Health-care workers (n=218) | Patients (n=33)* | Visitors (n=41)* | Patients and visitors (n=74) | Health-care workers (n=8)† | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 49 (0–95, 25–63) | NA | 30 (22–61, 26–34) | 62 (16–84, 48–68) | 55 (31–75, 46–59) | 57 (16–84, 46–65) | 38 (24–55, 33–39) | |

| Male | 320 (47%) | NA | 85 (39%) | 17 (52%) | 31 (76%) | 48 (65%) | 5 (63%) | |

| Underlying disease | ||||||||

| Any underlying disease | 311 (46%) | .. | .. | 24 (73%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Malignancy or immunosuppression | 195 (29%) | .. | .. | 12 (36%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Endocrine disease | 78 (12%) | .. | .. | 8 (24%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 50 (7%) | .. | .. | 6 (18%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Neurological disease | 40 (6%) | .. | .. | 1 (3%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Liver disease | 29 (4%) | .. | .. | 1 (3%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Respiratory disease | 28 (4%) | .. | .. | 3 (9%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Renal disease | 21 (3%) | .. | .. | 1 (3%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Location of stay in emergency room | ||||||||

| Group A | 117 (17%) | 122‡ (18%) | .. | 23/30 (77%) | 24/38 (63%) | 47/68 (69%) | .. | |

| Zone II | 57 (8%) | 58 (8%) | .. | 13/30 (43%) | 12/38 (32%) | 25/68 (37%) | .. | |

| Zone III | 22 (3%) | 26 (4%) | .. | 7/30 (23%) | 9/38 (24%) | 16/68 (24%) | .. | |

| Zone IV | 38 (6%) | 38 (6%) | .. | 3/30 (10%) | 3/38 (8%) | 6/68 (9%) | .. | |

| Group B | 58 (9%) | 58 (8%) | .. | 3/30 (10%) | 3/38 (8%) | 6/68 (9%) | .. | |

| Group C | 500 (74%) | 503‡ (74%) | .. | 4/30 (13%) | 11/38 (29%) | 15/68 (22%) | .. | |

| Dates of stay in emergency room | ||||||||

| May 27 to May 27 | 160 (24%) | 162 (24%) | 46 (21%) | 8/30 (26%) | 12/38 (32%) | 20/68 (29%) | 0 | |

| May 28 to May 28 | 162 (24%) | 162 (24%) | 0 (0) | 1/30 (3%) | 1/38 (3%) | 2/68 (3%) | 0 | |

| May 29 to May 29 | 190 (28%) | 190 (28%) | 97 (44%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| May 27 to May 28 | 77 (11%) | 83 (12%) | 21 (10%) | 14/30 (46%) | 20/38 (53%) | 34/68 (50%) | 0 | |

| May 27 to May 29 | 31 (5%) | 31 (5%) | 51 (23%) | 7/30 (23%) | 4/38 (11%) | 11/68 (16%) | 5/5 (100%) | |

| May 28 to May 29 | 55 (8%) | 55 (8%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 1/38 (3%) | 1/68 (1%) | 0 | |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Medical doctor | .. | .. | 91 (42%) | .. | .. | .. | 2/5 (40%) | |

| Nurse | .. | .. | 79 (36%) | .. | .. | .. | 3/5 (60%) | |

| Nursing assistant or radiology technician | .. | .. | 31 (14%) | .. | .. | .. | 0 | |

| Others | .. | .. | 17 (8%) | .. | .. | .. | 0 | |

Data are median (range, IQR), n (%), or n/N (%). MERS-CoV=Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. NA=not available.

Three patients and three visitors with confirmed infection were not included in the initial contact investigation (appendix p 5).

Three health-care workers (one security guard, one physician, and one patient transfer agent) with confirmed infection were not initially identified as contacts.

Five extra visitors were added to group A and three extra visitors were added to group C because there were two or more visitors with confirmed MERS-CoV infection per patient.

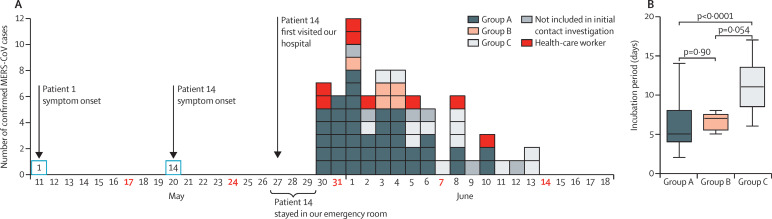

The epidemic curve of this emergency room-associated outbreak is shown in figure 2 . The incubation period was determined from 73 confirmed MERS-CoV cases: six cases were excluded because we could not determine the date of symptom onset, and data were not available from three visitors. The median incubation period was 7 days (range 2–17, IQR 5–10). Among 59 patients and visitors in groups A–C (excluding six who were not initially identified as contacts), the median incubation period was significantly shorter in group A than in group C (figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection by date of symptom onset after exposure to Patient 14 and (B) incubation periods

(A) 73 confirmed cases are shown here; six patients were excluded because we could not determine the date of symptom onset, and data were not available from three visitors. (B) Incubation periods were calculated from data of 59 patients and visitors in groups A–C. MERS-CoV=Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

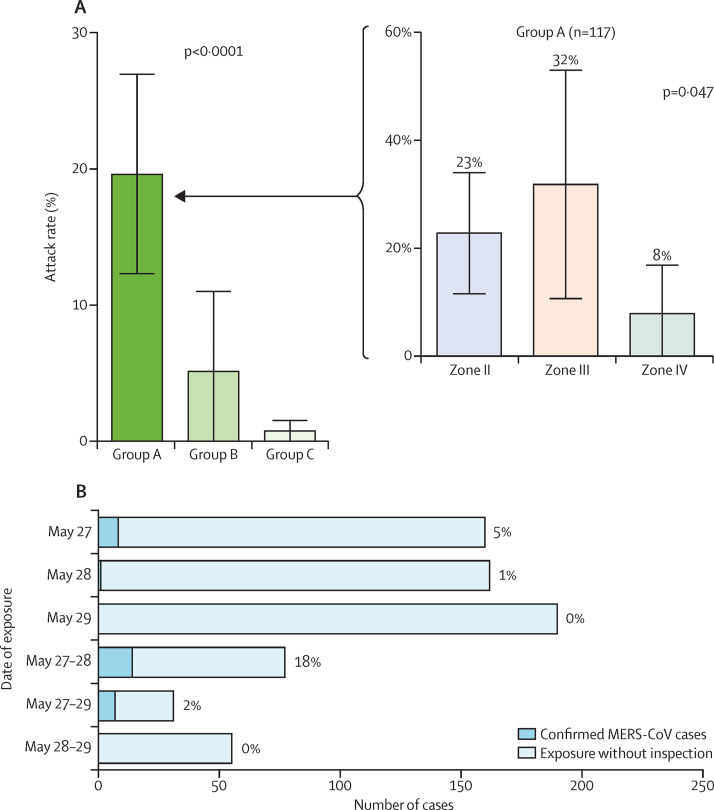

Excluding three patients with confirmed MERS-CoV infection who were not identified in the initial patient contact investigation (appendix p 5), the overall attack rate for patients in the emergency room was 4% (30 of 675). Patients in group A had the highest attack rate (20% [23 of 117]), compared with 5% (three of 58) in group B and 1% (four of 500) in group C (figure 3 ). After adjusting for age, sex, underlying disease, and groups, patients in group A had the highest risk for MERS-CoV infection (table 2 ). In group B, all three patients who had MERS-CoV infection had time overlap in the radiology suite with Patient 14.

Figure 3.

Attack rates (A) by groups of patient contacts and (B) by date of exposure

Error bars represent 95% CI. MERS-CoV=Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Table 2.

Risk factors for transmission of MERS-CoV in all patient contacts and in patients in group A

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All patient contacts (n=675) | |||

| Age (>60 years) | 1·43 (0·62–3·28) | 0·71 | |

| Male | 0·77 (0·35–1·71) | 0·48 | |

| Any underlying disease | 1·97 (0·79–5·41) | 0·12 | |

| Group | <0·0001 | ||

| A vs B | 4·32 (1·22–24·49)* | 0·016* | |

| A vs C | 25·59 (8·22–111·39)* | <0·0001* | |

| Group A (n=117) | |||

| Stay in the same zone as Patient 14 for >2 h | 1·74 (0·48–8·37) | 0·42 | |

| Location of exposure to Patient 14 | 0·010 | ||

| Zone II vs III | 0·91 (0·23–3·83)* | 1·00* | |

| Zone II vs IV | 5·62 (1·25–36·84)* | 0·019* | |

MERS-CoV=Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Bonferroni's correction.

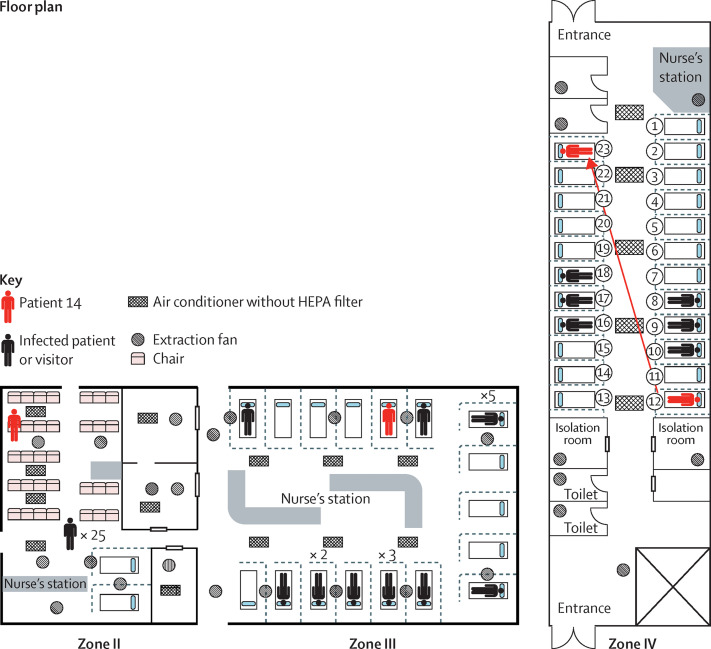

The median exposure time for patients in group A to Patient 14 was 3·0 h in zone II (range 0·5–10·3, IQR 1·9–4·5), 13·9 h in zone III (0·6–18·9, 6·3–18·4), and 17·4 h in zone IV (0·2–23·2, 9·2–21·4). The attack rates were 23% (13 of 57) in zone II, 32% (seven of 22) in zone III, and 8% (three of 38) in zone IV (figure 3). After adjusting for age, sex, underlying disease, and exposure time, staying in zone II was associated with a significantly higher risk for MERS-CoV infection than staying in zone IV (table 2). MERS-CoV transmission occurred in zone III, despite the fact that the distance from Patient 14's bed to the beds of other patients were as far as 6 m (figure 4 ). In zone IV, Patient 14 moved from bed 12 to bed 23, and six additional cases were documented in patients and visitors occupying beds in the middle of this zone, which were not adjacent to Patient 14's bed. No MERS-CoV infection was reported in patients and visitors who had been in the emergency room on May 29 during the time period when they were exposed only to zones II (n=81) or III (n=15), while Patient 14 was confined to zone IV. These patients were exposed to areas that were potentially environmentally contaminated but not to Patient 14 himself (figure 4). Under the assumption of one visitor per patient and excluding three visitors with confirmed MERS-CoV infection who were not identified in the initial visitor contact investigation (appendix p 5), the overall attack rate for visitors was 6% (38 of 683). The attack rates for patients and visitors were 20% (47 of 239) in group A, 5% (six of 116) in group B, and 2% (15 of 1003) in group C. Under the assumptions of two visitors per patient and four visitors per patient, the overall attack rates for visitors were 3% and 1%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Location of Patient 14 during his stay in the emergency room

HEPA=high-efficiency particulate arrestance.

218 health-care worker contacts were identified, and five (2%) developed MERS-CoV infection. Three health-care workers who were not initially identified as contacts (one security guard, one physician, and one patient transfer agent) developed MERS-CoV infection. Although they were not involved in the direct care for Patient 14, they visited the emergency room between May 27 and May 29. Only close contacts were furloughed and other health-care workers were isolated when they developed symptoms. There were no secondary cases from health-care workers among contacts during the their duty hours.

Discussion

We did a contact investigation of the MERS outbreak at the Samsung Medical Center by grouping exposed individuals on the basis of the extent of exposure to Patients 1 and 14. To our knowledge, we are the first to document group-specific incubation periods and attack rates. Our results showed the increased transmission potential of MERS-CoV from a single patient in an overcrowded emergency room setting. Overcrowding is an important issue for this outbreak and is also a common feature of modern medicine.

This study is unique because the index exposure occurred in a large emergency room in a tertiary-care centre, with electronic medical record information available to track the location and duration of exposure, thus enabling near-complete tracing of exposed contacts. The classic definitions of close contact as being within roughly 6 feet (1·8 m) or within the same room or care area for a prolonged period of time were difficult to apply to an emergency room setting with high patient volumes, ongoing traffic within the emergency room and to and from the radiology suite, and large numbers of visitors and family members. We considered all patients who visited the emergency room during the stay of Patients 1 and 14 as exposed contacts, developed criteria for close contacts by expanding on the definitions of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),12 and categorised patients into different groups. Therefore, we could establish group-specific viral incubation periods and attack rates during the outbreak. In close contacts who stayed in the same zone, the incubation period was shorter and attack rate was higher than patients who stayed in different zones. Additionally, in zones III and IV, patients were infected even when they were separated by curtains most of the time and were apart as far as 6 m (for beds on either side of the nurse's station; figure 4). Similar to the SARS outbreak, we observed so-called super-spreaders among patients with MERS-CoV infection, and these super-spreaders can cause large outbreaks through several modes of transmission similar to those in the SARS outbreak.13 Among patients who stayed in various locations, those who overlapped with Patient 14 at the radiology suite or registration area had higher attack rates (5%) than the rest of the patients (1%), suggesting that transmission might occur by even brief exposures to recently contaminated objects or encounters with individuals carrying a super-spreader.

Comparisons of environmental exposure and patient exposure also revealed unique findings. No patient developed MERS-CoV infection after exposure on May 29 only to the environment that had been potentially contaminated on May 27 (zone II) and May 28 (zone III) while Patient 14 was confined to zone IV on May 29. It is plausible that even if the environment was heavily contaminated by a super-spreader, the virus might not persist long enough in the environment to be capable of causing any new infection. Although patient exposure is clearly the most important factor in the spread of MERS-CoV, more research is needed to address the potential of environmental spread.14

Increased viral load and larger amounts of respiratory secretions have been suggested as the factors for SARS-CoV super-spreaders.15, 16 In this MERS outbreak, frequent ambulation of the index case could be considered as one factor related to high levels of viral transmission, in addition to large amounts of respiratory secretions and high viral load (cycle thresholds 18·6 for upE and 19·3 for ORF1a from Patient 1's sputum,17 and 16·2 for upE and 19·9 for ORF1a from Patient 14's sputum). Of note, Patient 1 infected 28 patients in another hospital but caused no confirmed secondary cases in our hospital, whereas Patient 14 caused an additional 82 cases in our hospital. The difference of transmissibility between these two individuals could be caused by a combination of factors such as the time from onset of disease, clinical symptoms, duration of contact exposure, pattern of behaviour inside and near the emergency room, and kinetics of viral shedding.

We showed that obtaining a travel history from patients is an important element of history taking by all physicians, and not only those specialising in infectious diseases or those working in infection control. Suspicion for unusual infections should be maintained if patients do not or cannot report accurate histories. Readiness of laboratory support is essential for initial investigation and for control of outbreaks, and overly rigorous requirements for laboratory testing have the potential to delay diagnosis and further spread disease. Hospital leadership needs to lead in preparedness for disaster management of high-risk communicable infectious diseases. Emergency preparedness at a national level and communication and support from government agencies are imperative to prevent and control any serious outbreak.

The results of this study need to be interpreted with caution because the study was not sufficiently powered to study risk factors for transmission. Some of our data were collected retrospectively. Analysis on visitors was limited because we did not have detailed data. Serological tests were not done simultaneously and attack rates were calculated on the basis of results from real-time RT-PCR of mainly symptomatic individuals. The potential transmission of MERS-CoV by asymptomatic carriers is under investigation.

In conclusion, we report a large nosocomial MERS outbreak that occurred outside the Middle East. The potential for similar outbreaks anywhere in the world from a single traveller should be noted, as long as MERS-CoV transmission continues in the Middle East. Emergency preparedness and vigilance are crucial to the prevention of further large outbreaks in the future. Our report serves as an international alarm that preparedness in hospitals, laboratories, and governmental agencies is the key not only for MERS-CoV infections but also for other new emerging infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere consolation for the patients and their families who had MERS-CoV infection. We greatly appreciate the efforts of all the hospital employees and their families at the Samsung Medical Center, who worked tirelessly during this outbreak. We also appreciate the cooperation of all other hospitals in South Korea that worked together to overcome the nationwide outbreak. We acknowledge the consultation and support of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the MERS Rapid Response Team of the Public-Private Joint MERS Task Force, WHO, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We also sincerely appreciate the discussion and critical feedback from Michael T Osterholm (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Janet A Englund (Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA, USA).

Contributors

SYC and J-MK designed the study and data collection methods, did the initial data analyses, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. YEH, who suspected and diagnosed the first case of MERS-CoV infection in South Korea, engaged in the management of MERS-CoV outbreak control at the Samsung Medical Center as an infectious disease specialist and reviewed the manuscript. GEP, JYeL, J-HK, JYoL, JMK, JGR, and JRC coordinated data collection, engaged in the management of MERS-CoV outbreak control at the Samsung Medical Center, and reviewed the manuscript. SK supervised data collection and analysis, analysed the data, and reviewed the manuscript. HJH, C-SK, and E-SK did laboratory tests for MERS-CoV detection, coordinated laboratory data collection, and reviewed the manuscript. C-IK, IJJ, KRP, H-JD, and J-HS supervised data collection and reviewed the manuscript. Y-JK and DRC conceptualised and designed the study, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final submitted manuscript.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—Saudi Arabia. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. http://www.who.int/csr/don/23-march-2016-mers-saudi-arabia/en (accessed March 29, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cauchemez S, Fraser C, Van Kerkhove MD. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:50–56. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breban R, Riou J, Fontanet A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet. 2013;382:694–699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61492-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowell G, Blumberg S, Simonsen L, Miller MA, Viboud C. Synthesizing data and models for the spread of MERS-CoV, 2013: key role of index cases and hospital transmission. Epidemics. 2014;9:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, Getz WM. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. 2005;438:355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature04153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riley S, Fraser C, Donnelly CA. Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions. Science. 2003;300:1961–1966. doi: 10.1126/science.1086478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen Z, Ning F, Zhou W. Superspreading SARS events, Beijing, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:256–260. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korea Centers for Disease Control Prevention Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak in the Republic of Korea, 2015. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2015;6:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehulster L, Chinn RY, CDC. HICPAC Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;6:1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS) Case definitions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/case-def.html (accessed June 11, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu IT, Li Y, Wong TW. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1731–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Munster VJ. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20590. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.38.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Severe acute respiratory syndrome—Singapore, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christian MD, Poutanen SM, Loutfy MR, Muller MP, Low DE. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1420–1427. doi: 10.1086/420743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JS, Park S, Kim YJ. Middle East respiratory syndrome in 3 persons, South Korea, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2084–2087. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.151016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.