Summary

In 2013, China proposed its Belt and Road Initiative to promote trade, infrastructure, and commercial associations with 65 countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe. This initiative contains important health components. Simultaneously, China launched an unprecedented overseas intervention against Ebola virus in west Africa, dispatching 1200 workers, including Chinese military personnel. The overseas development assistance provided by China has been increasing by 25% annually, reaching US$7 billion in 2013. Development assistance for health from China has particularly been used to develop infrastructure and provide medical supplies to Africa and Asia. China's contributions to multilateral organisations are increasing but are unlikely to bridge substantial gaps, if any, vacated by other donors; China is creating its own multilateral funds and banks and challenging the existing global architecture. These new investment vehicles are more aligned with the geography and type of support of the Belt and Road Initiative. Our analysis concludes that China's Belt and Road Initiative, Ebola response, development assistance for health, and new investment funds are complementary and reinforcing, with China shaping a unique global engagement impacting powerfully on the contours of global health.

Introduction

China's engagement with global health began in the 1960s when the government dispatched medical teams to Africa. Since restoring its membership in the UN in 1971 and entering the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has joined almost all multilateral organisations. Following rapid economic growth to become the world's second largest economy, China has transitioned very quickly from aid recipient to aid donor. A 2014 analysis1 showed that China had emerged as an important participant in global health, serving as an essential source of overseas development assistance (ODA) and development assistance for health (DAH), sharing concerns about cross-border infectious disease threats, joining in global health governance, and participating in global sharing of knowledge and technology.

Since 2013, China has steadily rolled out an ambitious One Belt One Road Initiative (also called the Belt and Road Initiative, the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, or the Belt and Road). The initiative has increasingly emerged as China's major vehicle for international engagement, with important health dimensions.2 In January, 2017, China's President Xi signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with WHO that endorsed international health regulation and promoted health security on the Silk Road.3 In May, 2017, China hosted the Road and Belt Summit in Beijing, which was attended by 29 heads of state and, in August, 2017, China launched the first of what will be biennial global conferences of health on the Belt and Road.4 More than 30 health ministers and leaders of multilateral agencies signed the Beijing Communique of follow-up priorities.5

What is China's 21st Century Belt and Road Initiative? How does this initiative relate to China's role in global health? How are China's major global health activities, such as Ebola response, ODA, and DAH, related to the initiative? And what are the implications for global health? Through analyses of quantitative and qualitative data, we discuss the rapidly developing Belt and Road Initiative and related global health activities.

Data and methods

Two government white papers on China's ODA published in 2011 and 2014 did not contain detailed data on DAH. China's ODA classification system differs from the standards used in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), and health-specific data were not reported. Our study collected quantitative and qualitative data on DAH and ODA in both Chinese and English. Analyses on the Belt and Road Initiative and Ebola are based on a literature search and publicly available documents. Quantitative data on China ODA and DAH are based on estimates from AIDDATA, which ascribed a value in US$ to 390 health and population-reproductive health projects from 2008 to 2013. Financial data on governance come from official documents of the Chinese Government, OECD DAC, UN agencies, and the World Bank (appendix).

China's Belt and Road Initiative

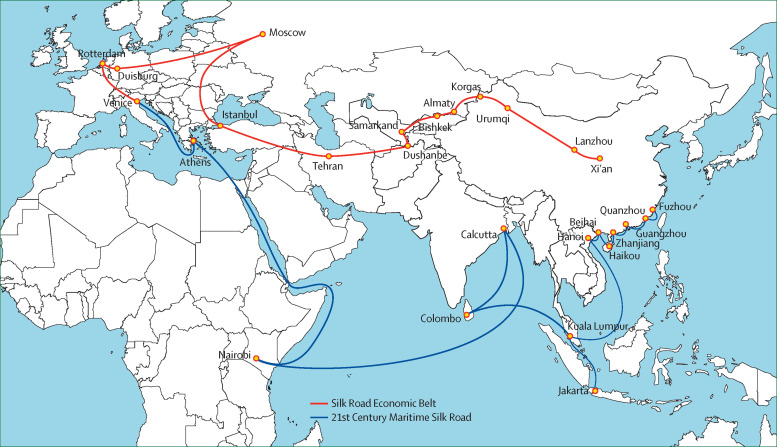

In 2013, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative to link China to Asia, Africa, and Europe (figure 1 ). Historically, the Silk Road was an ancient network of routes that facilitated trade and movement of the arts, culture, religion, knowledge, and medicine, and enhanced relations between people and between countries.6 China's Belt and Road Initiative of the 21st century is primarily a regional plan for economic integration, covering 65 countries that contain 70% of the world's population, 30% of global gross domestic product (GDP), and 75% of world energy reserves.7 The Silk Road has two routes. The Silk Road Economic Belt is a series of land-based economic corridors connecting China with countries in central and western Asia, the Middle East, and eastern and central Europe. The 21st century Maritime Silk Road will traverse the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Mediterranean, covering southeast and south Asia and extending into sub-Saharan Africa. Both the land and maritime routes eventually connect China, across Asia and Africa, to Europe.8

Figure 1.

Map of China's Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

The initiative is not a single project but a long-term strategy to boost the region's economic development by enhancing trade, infrastructure, and connectivity by building networks of railways, highways, bridges, airports, ports, oil and gas pipelines, and fibre optics. So far, China has reached bilateral agreements with about half of the proposed countries and, in 2016, Chinese enterprises reportedly signed nearly 4000 contracts, valued at US$93 billion, in 60 countries.9 Previous analyses8, 10 have estimated that China plans to invest up to 9% of its GDP into this initiative, an amount 12 times larger in absolute dollar value than the US-led Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of Europe after World War 2.

Although the Belt and Road Initiative is primarily economic, there are important health dimensions.11 China's National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) has set forth a 3-year (2015–17) strategic plan to promote development of health and safeguard health security on the Silk Road.12 In August, 2017, China hosted the Belt and Road High-Level Meeting to promote health cooperation. A concluding so-called Beijing Communique was adopted by more than 30 health ministers and high-level representatives from multilateral health agencies.5 Seventeen bilateral MoUs were signed between China and surrounding Silk Road countries and agencies such as UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS), the Global Fund, and Gavi (the Vaccine Alliance). The agreements covered many areas, such as health security, maternal and child health, health policy, health systems, hospital management, human resources, medical research, and traditional medicine. The Chinese Government plans to launch four networks—public health, policy research, hospital alliance, and health industry—to promote continuous exchange in the search for cooperative opportunities under the broader goal of advancing the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

As an ambitious venture, the Belt and Road Initiative is not a guaranteed success. Many barriers will have to be overcome, such as buy-in from neighbouring countries, cultural and linguistic differences, varying legal frameworks, and environmental sustainability. Questions have also been raised about the economic risks and viability of many proposed infrastructure investments.13 Although high-level meetings have provided a clearer scope for the Belt and Road health plans, there is an absence of measurable targets and prescribed indicators to evaluate success. Health appears to be both a valued goal and a necessary diplomatic instrument of the initiative.

Ebola and pandemics

From 2012–14, China launched an unprecedented response to the Ebola epidemic in west Africa. Ebola virus, which infected more than 28 600 people, caused more than 11 000 deaths and sparked China's largest ever health emergency overseas. China's State Council mobilised action across 23 ministries and departments, dispatching a Chinese team to west Africa days after the WHO declared Ebola an Public Health Emergency of International Concern. To do so, China mobilised its military medical cadres and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Altogether, about 1200 Chinese workers, including doctors, public health experts, and military medical officers, were deployed to west Africa.14, 15, 16 China opened a 100-bed treatment unit and established three field demonstration sites in Sierra Leone. The Chinese medical and public health professionals provided free treatment, and zero infection among these workers was achieved through intensive management and training.15, 17, 18, 19 In March 2015, China built a biosafety level-3 laboratory, transporting in all construction materials in only 87 days.14

There are probably several reasons for China's unprecedented response. China has a long-standing friendship and commercial linkages with Africa. Like other countries, China also sought to protect its own citizens, since there are about 1·1 million Chinese people living in Africa and an estimated 100 000 African migrants living in Guangzhou, China.20, 21 China tightened airport screening to avoid introduction of people with Ebola into the country, which could spoil its hosting of several major international events (eg, the Youth Olympics Games). Perhaps most importantly, the Ebola epidemic was reminiscent of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in China of 2002–03. SARS originated in China and spread to 37 countries, exerted a catastrophic effect on the Chinese economy, and almost halted its international trade. China's economic loss from this epidemic was estimated at $25·3 billion, slowing down GDP growth by 1–2% in 2003.16, 22 China was also widely criticised for concealing information and failing to comply with international health regulations. The importance of health security to China seemed to be confirmed when it signed two MoUs with WHO in 2017 on strengthening the international health regulation, especially on the Silk Road.

The response by China to the Ebola epidemic was an exceptional intervention because mobilisation of the military required Central Party directives beyond governmental ministries. In tackling Ebola, China learned the difficulties of overseas operational work: communications and operational barriers across ministries (foreign affairs, commerce, health, and the military), between headquarters and the front lines, and working across cultures. Applying China's experience in domestic disease control to Ebola, China instituted disease surveillance with community-based house-to-house case finding, contact tracing, community mobilisation, and health education in Sierra Leone.23 The Chinese workers learned that active surveillance and quarantine, which was effective during the SARS epidemic, requires strong management on the ground and compliant health-seeking behaviour, which can differ across cultures. The medical and public health teams concluded that China needs much stronger professional and organisational capability for future overseas work. Few of the Chinese workers sent to Sierra Leone had previous overseas experience. To sustain the newly built biosafety level-3 laboratory, training of local professionals and sustained funding beyond single-year emergency budgets were needed. Chinese professionals dispatched to fight Ebola have admirably published several papers on their experiences.14, 15, 18, 19 Although their success has been lauded, more systematic monitoring and evaluation is suggested by these studies.

China finally learned that effectively addressing epidemics would ultimately require international cooperation. Sometimes perceived as working in isolation, China cooperated with all groups in west Africa, including local government, bilateral donors, UN, multilateral groups, and non-government organisations. China offered five rounds of assistance, mostly in-kind, totalling $123 million to 13 west African countries.24 The Ebola epidemic stimulated China to sign a formal MoU with the USA so that the CDCs of both countries could work together to help establish an African CDC at a time of unsettled China–USA political relations.

Governance, aid, and investment

Governance in global health could be defined as protecting and promoting world health through collective action, using shared mechanisms and involving several public and private groups in an era of globalisation. Key functions of this governance are in standards and norm setting, policies and regulations, financing, stewardship, and other actions that advance shared global health goals.25, 26

China has become more proactive in global health governance. Early efforts have included participating in WHO agenda setting (on essential and traditional medicine and universal health coverage) and prioritising chronic disease, drug innovations, and social determinants of health in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.27 However, three areas of governance have dominated Chinese engagement. The first is the promotion of health security, as illustrated by the Ebola response and follow-up funding. The second is the Belt and Road Initiative, which will be accompanied by new multilateral institutional arrangements. The third is the sharp increase in China's financing of global health through DAH and ODA and new investment vehicles.

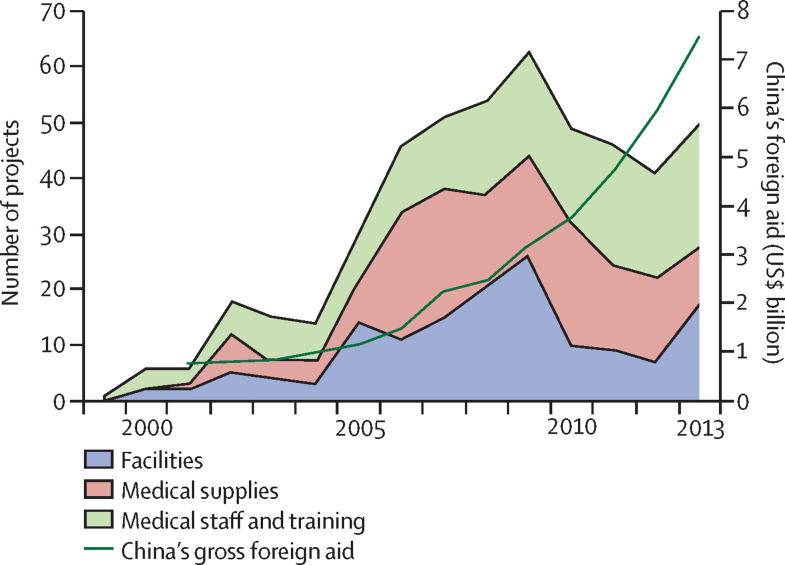

China's ODA has shown sharp increases since 2000 (figure 2 ). China's ODA in 2013 was $7 billion, having had annual increases of 25% over the previous 3 years. China's ODA is still lower than the contributions of other major OECD donors: the Chinese contribution is 23% of USA's $32 billion, 39% of UK's $19 billion, and 69% of Japan's $11 billion (table ). As a percentage of gross national income, China's ODA at 0·04% is lower than the OECD DAC target of 0·7%, and China's 7% health component of ODA is also lower than that of other donors. Arguably, these comparisons show a lag effect of a newly emerging economic power that is still developing its ODA modalities of work.

Figure 2.

China's foreign aid and number of projects funded by development assistance for health, 2000–13

Gross foreign aid is the amount spent in each year. Projects are classified by category of expenditure. Data are sourced from AIDDATA and the JICA Research Institute

Table.

China's ODA and DAH compared with the USA, UK, Japan, and the OECD DAC, 2010–13

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | ||||

| ODA | 3773 | 4705 | 6003 | 7462 |

| DAH | 468 | 347 | 340 | 489 |

| DAH as proportion of ODA (%) | 12% | 7% | 6% | 7% |

| USA | ||||

| ODA | 31 854 | 32 585 | 31 672 | 31 793 |

| DAH | 11 768 | 12 931 | 11 209 | 13 222 |

| DAH as proportion of ODA (%) | 37% | 40% | 35% | 42% |

| UK | ||||

| ODA | 14 968 | 14 971 | 14 967 | 19 132 |

| DAH | 2625 | 2690 | 3277 | 3964 |

| DAH as proportion of ODA (%) | 18% | 18% | 22% | 21% |

| Japan | ||||

| ODA | 9003 | 8357 | 8084 | 10 748 |

| DAH | 1121 | 968 | 1507 | 784 |

| DAH as proportion of ODA (%) | 12% | 12% | 19% | 7% |

| OECD DAC | ||||

| ODA | 133 258 | 131 839 | 126 749 | 133 951 |

| DAH | 24 622 | 25 390 | 24 633 | 28 058 |

| DAH as proportion of ODA (%) | 18% | 19% | 19% | 21% |

Data are shown as US$ million (calculated against US$ for each year present), unless otherwise indicated. OECD DAC members include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA. ODA=overseas development assistance. DAH=development assistance for health. OECD=Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. DAC=Development Assistance Committee.

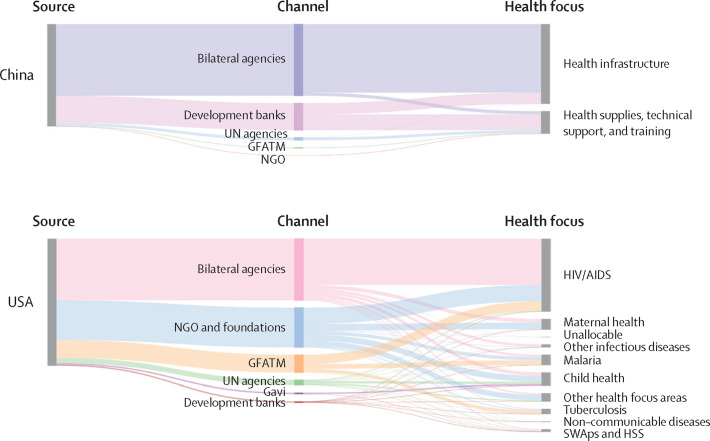

China's ODA is heavily concentrated in Africa (52%) and Asia (32%), matching the geography of the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. China's type of DAH differs from other donors. Of China's $21·9 billion ODA in 2010–13, nearly four-fifths (78%) were invested in infrastructure and a fifth (21%) in supplies and drugs. Modest funding was provided for technical assistance and training. China's well known medical staff, posting 23 000 medical teams in 66 countries over the past 50 years, constitute a shrinking share of its global health activities. The distinctiveness of Chinese channels of funding and categories of expenditure compared with those of the USA is shown in figure 3 , which depicts the channels and health focuses of DAH from both countries. The USA has both bilateral and multilateral channels of funding, which focus on specific diseases like HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, and on maternal and child health. American non-governmental organisations and foundations provide supplemental resources. Chinese funding, by contrast, is almost entirely governmental and is focused on providing medical facilities, supplies, and equipment. China has few non-governmental organisations that work overseas, and the wealthy Chinese have yet to begin overseas health philanthropy.

Figure 3.

Channel and health focus of developmental assistance for health in 2013 from (A) China and (B) USA

Data taken from AIDDATA and the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. GFATM=Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. NGO=non-governmental organisations. SWAps=sector-wide approaches. HSS=health sector support.

Two-thirds of China's ODA is channelled bilaterally, although China's contributions to multilateral mechanisms have been growing. WHO, with a Chinese former Director-General, seemed to be favoured among multinational agencies as China became the third largest donor to WHO's unrestricted budget. Immediately after the August, 2017 conference, China pledged an additional $20 million for pandemic control along the Silk Road. By contrast, China has contributed modestly to other UN agencies (Unicef, United Nations Population Fund, and UNAIDS) and the Global Fund.

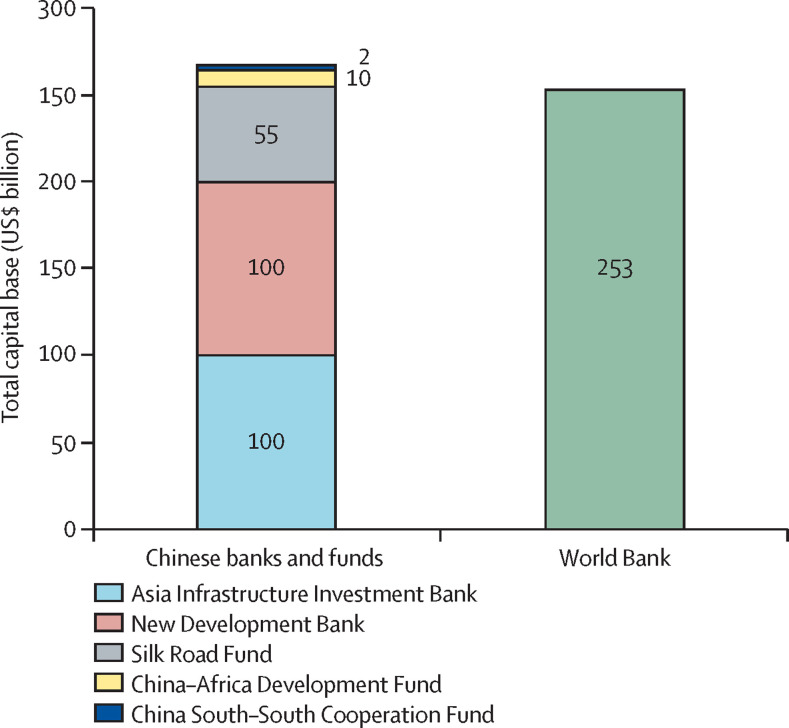

Crucially, China is not confining itself to the existing multilateral architecture. Since China had been unable to secure its share in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank on the basis of its weight in the global economy, China has embarked on establishing its own multilateral investment vehicles. These new multilateral funds are quite substantial, with China securing major pledges that total $267 billion. These pledges include $100 billion from Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), $100 billion from New Development Bank, $55 billion from the Silk Road Fund, $10 billion from the China–Africa Development Fund, and $2 billion from the China South-South Cooperation Fund. The sum of these new funds exceeds the total capitalisation of the World Bank of $253 billion (figure 4 ). It is of note that three of the larger funds are for-profit investment vehicles, consistent with the commercial objectives of China's Belt and Road Initiative; only the smallest, the China South-South Cooperation Fund is concessionary ODA.

Figure 4.

Total capital base of Chinese banks and funds and the World Bank in 2015

Of these funds, the most important could be AIIB, which is designed to serve the infrastructure needs of 56% of the world's population, making up 48% of the global GDP. With a robust capital base, AIIB will probably follow the World Bank model of low-interest loans. predominantly for infrastructure projects. The Articles of Agreement of the AIIB has been ratified by 15 of the world's 20 largest economies, including Germany, France, and the UK. China has 8·8% of the shares of AIIB equity, followed by India (8·3%) and Russia (6·6%). Notably, the USA and Japan declined to join, which was hypothesised to be because of fear that AIIB would duplicate or compete with the World Bank, be biased towards Chinese political objectives, or have lower lending standards, especially regarding the environmental effects of projects. Even though AIIB is primarily focused on infrastructure, this bank will still make China an important player in global health, since social and health developments are among its charter mandates. Of the World Bank's total investments of US$36 billion in 2016, investment for health constitutes only 5% of its lending.28 Yet, the World Bank is an indisputable major actor in global health.

Discussion

What will China's work in global health look like over the next 5 years? Steady increases of ODA and DAH and provision of supplies for infrastructure are likely to grow. Geographically, China will build upon its focus on the Silk Road in Africa and Asia. Asia is a growing proximal market, and Africa's largest trading partner and foreign investor is China.28, 29 Despite our analytical efforts, we could not find any correlation between China's DAH distribution and China's trade, import of energy, or market exports to individual African countries. Beyond economics, ODA and DAH allocations might be used for political purposes, enhancement of soft power, and humanitarianism, as shown by Chinese medical teams being sent to Africa when China was still very poor and isolated.

What are the prospects of China assuming a greater contributory role in multilateral programmes? There are important worries about the stability of funding pledges by some donors. Although China's ODA and DAH will remain mostly bilateral and country-focused, China is likely to pursue increasing cooperation with multilateral initiatives like Global Fund, Gavi, and UNAIDS, and to align its relevant health agreements under the Belt and Road Initiative theme, such as the ASEAN–China, Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation, China–Central and Eastern Europe 16 + 1, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor. However, China has also launched its own multilateral funds and banks. Thus, it seems very unlikely that China would simply fill large gaps in funding vacated by other donors. Cooperative ventures might be pursued but not simply on terms established by the existing multilateral framework. For example, increased interconnectivity along the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road will not only bring about international health risks but also new opportunities for cooperation. To this end, China has joined the UN Development Programme in seeking to advance the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals, especially in the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road countries.30 Notably, China has reaffirmed its commitment to the Paris Accord on climate change, although the Belt and Road Initiative plans are largely silent on the health dimensions of global warming.

More broadly, China's Belt and Road Initiative is its first global initiative outside the boundaries of the international relations framework established by so-called western powers in the past two centuries.31 China appears to be selectively joining some established multilateral mechanisms (such as the World Trade Organization and WHO) while also charting out its own multilateral mechanisms in others (AIIB). Indeed, China has reaffirmed its commitment to the Paris Climate Accord, despite the announced withdrawal of the USA. Like all major powers, China's participation in multilateral governance will be driven by its geopolitical and economic goals. China is the world's largest trading nation that, in 2013, had a total trade volume of $4 trillion, surpassing the USA.32 China also has about $3 trillion in foreign reserves, and investing abroad will enable the Chinese to make use of idle reserves and promote the Chinese reminbi as a global currency. The Belt and Road Initiative will also harness China's surplus capacity in steel output and state-owned enterprises for building infrastructure. Chinese firms also are confident that they will be competitive in winning contracts of new projects. Since trade will promote the movement of goods, people, and infectious diseases, health protection against pandemic diseases will be essential to achieve economic goals.29 Beyond SARs, China has experienced exportation of infectious diseases from adjacent countries on its western borders, such as polio virus from Pakistan and malaria from southeast Asia.33, 34

The future of China's global health policy will be shaped, in part, by Chinese professional and organisational capabilities. China has few global health professionals with field experience and there are limited career paths or incentives for global health work. Indeed, China has not yet filled its allocated share of positions in UN organisations, given the small pool of its human resources for global health. China's medical universities are just starting work in global health research and education.35 Global health knowledge, engagement, and support from the Chinese public is just beginning. The Ebola epidemic and the Belt and Road Initiative, nevertheless, sparked the creation of two new departments dedicated to global health. A NHFPC vice minister has been assigned a newly created portfolio in global health, and the Chinese CDC has established a new global health department. A draft statement about China's global health policy has been circulating for review, and there are active discussions about revamping the NHFPC's Department of International Cooperation, traditionally a health aid-receiving agency, into an outward-looking global health agency. These new health bodies will inject a stronger health component into China's ODA policy, which is under the coordination of the Foreign Aid Department of the Ministry of Commerce. For historical reasons, only China's medical teams are managed directly by the NHFPC; all other health-related projects are planned and managed by the Ministry of Commerce. Over time, the NHFPC might be expected to assume greater responsibility and authority for China's global health work.

As China brings stronger professional and organisational capabilities into its global health work, China will surely articulate a formal global health policy. The August Beijing Communique is, in essence, a Chinese policy statement on its global health priorities. A more comprehensive policy statement would be likely before the next Belt and Road High-Level Meeting for Health Cooperation in 2019. Like with all major powers, China's Belt and Road Initiative, Ebola response, ODA and DAH, and new investment funds are complementary and reinforcing, shaping a unique engagement, with China serving an increasingly powerful role in shaping the contours of global health.

For the China foreign exchange reserves see http://www.tradingeconomics.com/china/foreign-exchange-reserves]

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Chunyan Li, Yingxi Zhao, Jingmiao Long, Yuning Liu, Liang Zhang, Chunshan Zhao, and Hanyu Wang for their assistance in data collection and editing figures.

Contributors

KT did a literature search, data collection, and analysis and interpretation, compiled tables and figures, and wrote the first draft. ZL did a literature search, compiled data and figures, and interpreted data in revisions of the manuscript. WL suggested revisions to the draft manuscript. LC contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation, and coordinated manuscript finalisation.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Liu P, Guo Y, Qian X, Tang S, Li Z, Chen L. China's distinctive engagement in global health. Lancet. 2014;384:793–804. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60725-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu R, Liu R, Hu N. China's Belt and Road Initiative from a global health perspective. Lancet Glob Heal. 2017;5:e752–e753. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu G, for National Health and Family Planning Commission Building the Silk Road with health. http://en.nhfpc.gov.cn/2017-01/20/c_71075.htm (accessed July 18, 2017).

- 4.Jaspal ZN, for Pakistan Observer CPEC & OBOR: portents of progress. http://pakobserver.net/cpec-obor-portents-progress/ (accessed July 18, 2017).

- 5.National Health and Family Planning Commission Beijing Communique, Silk Road-Belt High Level Health Conference. Aug 18, 2017. http://en.nhfpc.gov.cn/2017-08/18/c_72257.htm (accessed Aug 30, 2017).

- 6.Sen A, for the New York Review of Books Passage to China. Dec 2, 2004. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2004/12/02/passage-to-china/ (accessed Oct 10, 2017).

- 7.European Parliament One Belt, One Road (OBOR): China's regional integration initiative. July 7, 2016. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2016)586608 (accessed Feb 28, 2017).

- 8.Luft G, for Foreign Affairs China's infrastructure play: why Washington should accept the new Silk Road. Sept 1, 2016. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/china-s-infrastructure-play (accessed Feb 8, 2017).

- 9.The Economic Times China's mega Silk Road project hits road blocks. May 8, 2016. http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/chinas-mega-silk-road-project-hits-road-blocks/articleshow/52175264.cms (accessed Feb 28, 2017).

- 10.Curran E, for Bloomberg China's Marshall Plan. Aug 7, 2016. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-08-07/china-s-marshall-plan (accessed Feb 28, 2017).

- 11.Nikogosian H, for Global Policy The New Silk Road—a health diplomacy and governance perspective. April 19, 2017. http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/19/04/2017/new-silk-road-%E2%80%93-health-diplomacy-and-governance-perspective (accessed Sept 8, 2017).

- 12.National Health and Family Planning Commission. NHFPC's implementation plan for the Belt and Road medical and health cooperation (2015–2017). Oct 14, 2015.

- 13.Pethiyagoda K, for Brookings What's driving China's New Silk Road, and how should the west respond? May 17, 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2017/05/17/whats-driving-chinas-new-silk-road-and-how-should-the-west-respond/ (accessed July 23, 2017).

- 14.Huang Y. China's response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Global Chall. 2017;1:1600001. doi: 10.1002/gch2.201600001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Y, Rong G, Yu SP. Chinese military medical teams in the Ebola outbreak of Sierra Leone. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162:198–202. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2015-000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei P, Cai Z, Hua J. Pains and gains from China's experiences with emerging epidemics: from SARS to H7N9. Biomed Res Int. 2016:5717108. doi: 10.1155/2016/5717108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Yin H, Liu D. Zero health worker infection: experiences from the China Ebola treatment unit during the Ebola epidemic in Liberia. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;11:262–266. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu X, Huang J, Yang H. The Chinese Ebola Diagnostic and Treatment Center in Liberia as a model center. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2015;4:e71. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo Y, Song C, Zhang H, Wang Y, Wu H. Toward sustainable and effective control: experience of China Ebola Treatment Center in Liberia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;50:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Politzer M, for Migration Policy Institute China and Africa: stronger economic ties mean more migration. Aug 6, 2008. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/china-and-africa-stronger-economic-ties-mean-more-migration (accessed March 6, 2017).

- 21.Li A. Chinese immigrants in international political discourse: a case study of Africa. West Asia and Africa. 2016:76–97. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hai W, Zhao Z, Wang J, Hou ZG. The short-term impact of SARS on the Chinese economy. Asian Econ Pap. 2004;3:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong Z, for ChinaNews Chinese public health training program reaches a new stage in Sierra Leone. March 11, 2015. http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2015/03-11/7120794.shtml (accessed March 1, 2017).

- 24.Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Republic of Liberia On China's assistance to Africa in the fight against Ebola. http://lr.china-embassy.org/eng/sghdhzxxx/t1207680.htm (accessed Feb 28, 2017).

- 25.Gostin LO, Mok EA. Grand challenges in global health governance. Br Med Bull. 2009;90:7–18. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kickbusch I, Gleicher D, for World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Governance for health in the 21st century. 2012. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/171334/RC62BD01-Governance-for-Health-Web.pdf (accessed Feb 24, 2017).

- 27.Chan LH, Chen L, Xu J. China's engagement with global health diplomacy: was SARS a watershed? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dieleman J, Murray CJL, Case MK, for Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Financing global health 2016: development assistance, public and private health spending for the pursuit of universal health coverage. 2017. http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/financing-global-health-2016-development-assistance-public-and-private-health-spending (accessed July 4, 2017).

- 29.Horton R. China's rejuvenation in health. Lancet. 2017;389:1086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations Development Programme A new means to transformative global governance towards sustainable development. May 9, 2017. http://www.cn.undp.org/content/china/en/home/library/south-south-cooperation/a-new-means-to-transformative-global-governance-towards-sustaina.html (accessed July 10, 2017).

- 31.Lampton DM. China's rise in Asia need not be at America's expense. In: Shambaugh D, Ash RF, Bush R, editors. Power shift: China Asia's new dynamics. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA, USA: 2005. pp. 306–326. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monaghan A, for The Guardian China surpasses US as world's largest trading nation. Jan 10, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/jan/10/china-surpasses-us-world-largest-trading-nation (accessed March 2, 2017).

- 33.Luo HM, Zhang Y, Wang XQ. Identification and control of a poliomyelitis outbreak in Xinjiang, China. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1981–1990. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subbarao SK. The Anopheles culicifacies complex and control of malaria. Parasitol Today. 1988;4:72–75. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(88)90199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu DR, Cheng F, Chen Y, Hao Y, Wasserheit J. Harnessing China's universities for global health. Lancet. 2016;388:1860–1862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31839-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.