Abstract

Although China's 2009 health-care reform has made impressive progress in expansion of insurance coverage, much work remains to improve its wasteful health-care delivery. Particularly, the Chinese health-care system faces substantial challenges in its transformation from a profit-driven public hospital-centred system to an integrated primary care-based delivery system that is cost effective and of better quality to respond to the changing population needs. An additional challenge is the government's latest strategy to promote private investment for hospitals. In this Review, we discuss how China's health-care system would perform if hospital privatisation combined with hospital-centred fragmented delivery were to prevail—population health outcomes would suffer; health-care expenditures would escalate, with patients bearing increasing costs; and a two-tiered system would emerge in which access and quality of care are decided by ability to pay. We then propose an alternative pathway that includes the reform of public hospitals to pursue the public interest and be more accountable, with public hospitals as the benchmarks against which private hospitals would have to compete, with performance-based purchasing, and with population-based capitation payment to catalyse coordinated care. Any decision to further expand the for-profit private hospital market should not be made without objective assessment of its effect on China's health-policy goals.

Introduction

China has pledged to provide affordable, equitable access to quality basic health care for all its citizens by 2020. To achieve this goal, China launched a nationwide systemic reform in 2009, supported by infusions of substantial public funding. The reform marked a departure from the market-oriented strategy used after the liberalisation of the economy in 1978, and re-instated the government's role in the financing of health care and provision of public goods. In only 4 years, the reform produced substantial positive results in expansion of insurance coverage and strengthening of the infrastructure of primary health-care facilities, but much still needs to be done to reform China's health-care delivery. Particularly, China faces major challenges in transformation of its underperforming hospital-centric, fragmented system into one that delivers high-quality and efficient care to meet the emerging health needs and rising patient expectations associated with rapid ageing, environmental deterioration, urbanisation, and other socioeconomic transformations.

An addition to this ongoing challenge is the government's latest decision to open up the hospital sector for private investment, signalling a major swing back towards the market along the government-market pendulum guiding health-care policy.

What are the implications of a pro-market policy on China's health-care delivery system, in view of the fact that China already has a very hospital-centred system dominated by public hospitals mainly driven by profit? What alternative pathways might China consider if it were to achieve its health-policy goals? In this Review, we aim to provide informed speculative answers to these questions, using social policy and economic theories, China's past experiences, and international lessons.

We provide an update on China's 2009 reform, the progress and challenges of the reform, and the government's latest plans. We then suggest a more cost-effective and high-quality health-care delivery approach as a rational direction for China to aim for, discuss whether China is on track towards this vision, and what alternative pathways it might consider.

China's current health-care system and the latest government policies

In response to growing public discontent with unaffordable access to health care, little financial risk protection from out-of-pocket spending on health, and a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak that emphasised weaknesses in the health-care system, China took a giant step to reform its health sector in 2009. Guided by the principle of equity, the reform departed from the previous market approach and re-instated the government's role in health care, increasing annual public spending from ¥481·6 billion to ¥836·6 billion (US$1 is roughly equal to ¥6·5) between 2009 and 2012.1 Before the reform, there was heated debate about whether additional government funding should be given as a direct budget to the providers (supply-side approach) or channelled through insurance programmes that then purchase services from providers (demand-side approach).

Key messages.

-

•

China's 2009 reform has produced substantial results in expansion of insurance coverage, but unless the wasteful and inefficient delivery system is reformed, China cannot achieve affordable and equitable access to quality health care for all its citizens

-

•

Privatisation of an already profit-driven public hospital sector combined with a hospital-centric fragmented delivery system would result in health-care expenditure escalation, with patients bearing increasing costs; a two-tiered system in which access and quality of care are decided by ability to pay; and poor population health outcomes

-

•

Benchmark competition between public and private sectors, with public hospitals reformed to pursue the public interest and be held accountable for population outcomes, offer an alternative pathway to steer China back on course to achieve its health-policy goals

-

•

Objective monitoring and assessment are essential to support evidence-based reform, and any decision to further expand the for-profit private hospital market should not be made without objective assessment of its effect on China's health-policy goals

The government decided that most additional finance should be used to subsidise rural and urban residents not already covered by the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) programme to enrol in the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) or the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance programme (URBMI), respectively. The government also directly paid primary health-care providers to deliver a defined package of public health services. This, together with the services covered by these three health insurance programmes (hereafter referred to as social health insurance [SHI]), constitutes the basic health care financed by the government. To strengthen the primary health-care networks, the reform invested in infrastructure and provider training, and established the Essential Medicine Program to improve the safety, quality, and efficiency of primary health-care services. Finally, unable to decide on a viable strategy to reform public hospitals, the government initiated various pilots.2

The 12th 5-Year Plan for Health (12th FYP), announced in 2012, reconfirmed the government's commitment to the ongoing reform and set new targets for 2015, including further increases in government funding for NCMS, URBMI, and public health services; continued improvements in primary health-care infrastructure and training of general practitioners; and an expansion of the essential drugs list. The government is moving towards integration of all three existing insurance programmes, starting with the NCMS and URBMI schemes initially, to increase risk pooling and equalise benefit packages.3 Table 1 describes the 2009 reform, its progress and challenges, and the government's short-term plans.2, 3, 4, 5

Table 1.

Overview of China's health-care reform

| Description | Progress so far | Plans forward and challenges | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expand health insurance coverage | The government subsidises each rural and urban resident not covered by the UEBMI programme to enrol in the NCMS or the URBMI, respectively | By now, NCMS, URBMI, UEBMI together cover more than 96% of the population Service coverage has gradually been expanded from its initial focus on hospital admission to include outpatient services. Chronic diseases and major disorders that incur high expenditures have also been prioritised for reduced copayment |

Further increase in premium subsidies for the NCMS and URBMI schemes to ¥360 RMB per capita by 2015 (up from ¥80 in 2009) Higher NCMS and URBMI reimbursement rates to cover at least 75% and 50% of expenditures for hospital admissions and outpatient services, respectively, and additional insurance for selected groups of diseases with high expenditures Integrate NCMS, URBMI, and UEBMI into one risk pool for each locale Challenges: financial sustainability of the schemes if health expenditure growth is not managed |

| Equalise public health services for all | The government funds primary health-care providers to deliver a defined package of basic public health services, including health promotion and prevention; immunisation and vaccinations; infectious disease control; secondary prevention for hypertension and diabetes; management of psychotic patients; health examinations for pregnant women, children, and elderly people and compilation of electronic health records for every resident. These services are provided free for users | Reported statistics suggest that most of the government-set targets have been met | Funding would further increase to ¥40 per head by 2015 (up from ¥15 in 2009) to increase service coverage of the defined package of public health services Challenges: the quality of services are unknown |

| Strengthen primary health care | Building and strengthening of infrastructure for primary health care with a focus on rural areas Improvement of workforce: waiving tuition fees for medical students willing to work at rural primary health-care facilities for 3 years after graduation; recruitment to meet a target of one licensed physician per township health centre; selection of physicians from county hospitals to receive on the job training in tertiary hospitals; and encouragement of experienced physicians to rotate to county hospitals to train staff |

2200 county hospitals, more than 330 000 community health centres, township health centres or village posts rebuilt or upgraded | Continue with infrastructure building, general practitioner training, stabilisation of the workforce through training and improved compensation, establishment of a referral system Challenges: Patients still bypass primary health-care facilities and most visits are concentrated at hospitals. Primary health care not performing gatekeeping functions No data have been reported for the quality or equitable distribution of services |

| Establish essential medicines programmes | Establish national essential drug list: should selection of drugs be based on disease burden needs, safety and clinical efficacy, affordability, past use patterns, and availability of supply Establish province-based centralised procurement system Remove mark-up for drugs at primary health-care facilities |

All public primary health-care facilities have used the zero drug mark-up policy Zero drug mark-up policies extended to county hospitals The national essential medicines list and province-based centralised-procurement system has been used in all provinces for public primary health-care facilities. Most provinces have formulated supplementary lists |

Improve bidding mechanism Expand items on essential drug lists, encourage generic substitutions, expand drugs for chronic disease and child health conditions, remove drugs with low frequency of use Reduce prices of drugs on essential drug lists Challenges: Local supplements of essential drug list do not seem to be based on cost-effectiveness; rather they are determined by interest groups Kickbacks still exist and therefore providers have not delinked drug revenue from income. No evidence that appropriate drug prescription has improved |

| Pilot public hospital reform | Do pilots in 17 cities along the following four areas: separation between ownership and regulation; separation of government administration from hospital management; separation between for-profit and not-for-profit; and separation between drug sales and hospital revenues | Little progress | Increase market share for private hospitals to 20% |

UEBMI=Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance. NCMS=New Cooperative Medical Scheme. URBMI=Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance.

At present, 96% of the population is covered by one of the three insurance schemes. However, progress in service delivery reform has been slow. Despite substantial investment in infrastructure and training at the primary health-care level, visits and admissions continue to take place mainly at secondary and tertiary hospitals.6 Primary health-care facilities have not been able to perform a gate-keeping function, and health-care delivery remains hospital-centred and fragmented. Public hospital reform has been stymied. Pilots in 17 cities yielded few lessons for guiding policy formulation. Premier Li Keqiang described China's health-care reform as having entered the “deep water zone”, especially in reference to the difficulties of reformation of profit-driven public hospitals.7

Between 2007 and 2012, real per capita total health expenditure and gross domestic product increased at annual rates of 14·9% and 10·2%, respectively.1 Subsequently, although expansion of health insurance coverage has led to increases in insurance reimbursement, it has neither reduced illness-related financial burdens faced by households nor improved quality of care.2, 8 If health expenditure continues to grow unabated, the sustainability of the insurance programmes will be at risk, with patients ultimately bearing the cost.

The 12th FYP set forth a programme for the reform of public hospitals, including delinking drug sale revenue from staff remuneration, changing of provider payment methods, testing of alternative corporate governance structures, improvement of supervision of quality and rational drugs, and use of more efficient management,4, 5 most of which have been initiated in the 2009 reform pilots.

The most striking announcement is the government's decision to promote private investment in the hospital sector, with the target of private hospitals reaching a 20 percent market share by 2015.4, 5, 9, 10 Although not made explicit, the motivation behind privatisation can be interpreted partly as a strategic move to use private sector competition to stimulate changes in the otherwise stymied public hospital reform, partly as a swing back in government ideology towards a more pro-market approach to improve productivity in the health sector, and partly naively treating the health sector as another sector to boost the economy. The rationale of the 20% target and whether the government intends further market expansion beyond 2015 remains unknown. Companion policies putting private hospitals on equal footing with public hospitals are being introduced—eg, the three insurance schemes would contract with private hospitals, and physicians working in the private hospitals would qualify for promotion within the medical professional ranking system.11 At the same time, no new building projects or expansion of public hospital beds will be approved. How the government plans to regulate the private hospitals and, more importantly, can regulations be effectively enforced in the Chinese context, are both open questions at the moment. Overall, whether additional government financing would produce effective health care that serves the needs of its population depends crucially on whether China can find a workable and sustainable strategy to reform its delivery system.

A more cost-effective and higher-quality health-care delivery approach

Similarly to other emerging economies, China faces increasing pressure on its health-care system from a combination of demographic, environmental, economic, and epidemiological forces12 (appendix). With a population increasingly affected by non-communicable diseases and disabilities associated with ageing,13, 14, 15, 16 a more cost-effective approach of delivery is a primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model, which focuses on population-based prevention, health promotion, and disease management, with functioning coordination between primary, secondary, and tertiary health-care providers, and possibly links to social care. In this approach, primary health care plays a central part in prevention, case detection and management, gatekeeping, referral, and care coordination.

The primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model can take many structural and organisational forms. They can range from fully integrated models that combine primary health care and hospital services into one delivery system that includes all aspects of care for a defined population, to the more common disease management programmes, which are narrower approaches to coordinated care with a focus on population groups with specific health conditions. Unlike fully integrated models, disease management programmes do not usually include major structural changes to the health-care system. Instead, they integrate care decisions usually through a care coordinator (for the purpose of this Review, we do not differentiate integrated and coordinated care).17, 18 There are also attempts to integrate medical and social care for an ageing population with multimorbidities.19

Panel 1 describes existing evidence on the effects of integrated care. The scientific literature shows that integrated care encompasses a wide range of interventions whose effects are dependent on the specific design of the programme and the contexts in which they are implemented. A synthesis of evidence from 19 systematic reviews suggests that available evidence “points to a positive impact of integrated care programmes on the quality of patient care and improved health or patient satisfaction outcomes but uncertainty remains about the relative effectiveness of different approaches and their impacts on costs”.31 However, it remains “challenging to interpret the evidence from existing primary studies, which tend to be characterised by heterogeneity in the definition and description of the intervention and components of care under study”.31 The authors also emphasise the importance of assessment of integrated care as a complex strategy to innovate and implement long standing change in service delivery that includes several changes at many levels, rather than one intervention.31

Panel 1. Examples of integrated care and evidence of its effects.

Integrated care schemes differ widely in the degree of integration, target population, and scope of interventions.20, 21 Fully integrated models are uncommon. Kaiser Permanente and the Veterans Health Administration (VA) in the USA are rare examples. Findings from one study22 showed that when Kaiser Permanente stratifies its patients into levels of care and enrols high-risk patients into specific disease management programmes for more intensive case management, the percentage of hypertensive patients with blood pressure under control has more than doubled and admissions to hospital for coronary heart disease and stroke decreased by 30% and 20%, respectively, between 1998 and 2007. Findings from other studies showed that participants in the Care Coordination/Home Telehealth programme for diabetes in the VA were 50% less likely to be admitted to hospital and 11% less likely to have an emergency room visit 1 year after enrolment.23, 24, 25 However, these results were based on before and after comparisons.

Results from assessments of disease management programme are mixed, in large part dependent on the specific programme designs, the population covered, and the contexts in which the intervention took place. Ofman and colleagues26 reviewed 102 studies representing 11 chronic conditions to assess the clinical and economic effects of disease management. They identified that in patients with depression, high cholesterol, cardiac insufficiency, high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes, those who received coordinated care were more likely to see improvements than were patients in control groups who received normal care.26 Gohler and colleagues27 did a meta-analysis of 36 studies spanning 13 countries that compared the coordinated management with care of congestive heart failure and identified a 3% reduction in mortality and an 8% reduction in re-hospitalisations, compared with regular care. Kruis and colleagues28 reviewed randomised controlled trials assessing integrated disease management programmes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and noted that integrated programmes reduced hospital admissions and length of stay but had no effect on mortality between comparison and control groups. However, another Cochrane review29 on integration of services that are usually delivered through vertical programmes, such as HIV/AIDS, family planning, and maternal child health into primary health services in low-income and middle-income countries, showed no evidence of improved health-care delivery or health status. This Review differs from others in looking at integration of several services for different health conditions in one health-care provider, rather than coordination of different providers involved in treating one health condition. Similarly, the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration—a systematic assessment of disease management and care coordination—identified no difference in hospital admissions in 13 of 15 randomised controlled studies and no effect on Medicare expenditures overall between 2002 and 2006. However, the 15 selected host programmes differed widely in their organisational structure, target populations, and approach to coordination. The authors note the potential of replication of results from the two successful programmes by promotion of key programme features. These features included frequent in-person patient contact with coordinators, close ties between care coordinators and physicians, and links with local hospitals to ease the transition after hospital admission.30

Examples of integrated care for elderly people include the North American Programme for All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) in the USA and the Torbay Care Trust in the UK. Although the first targets elderly people who live in communities within a set service area, Torbay focuses on high-risk patients who need intensive ongoing support from community nurses and wider integrated teams. Both programmes experienced a decrease in inpatient and nursing home use, especially emergency visits, and an increase in home and community-based services. PACE also decreased Medicare costs in comparison to non-enrolees, whererase Torbay delivered improved system performance at no additional cost.19 Generally, rigorous assessments of integrated care for the elderly population are scarce because many of them are relatively new.

The state of knowledge on integrated care is still in its early stages. In practice, there is no single model of the primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model that would fit all nations. Many countries (even those with advanced economies) still experiment with models that suit their contexts best. However, a primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model, that focuses on population-based prevention and care coordination offers a rational course for China to pursue given the changing needs of its population. Similar to other nations that have embarked on this course, China would have to innovate and discover its own model, accompanied with objective and ongoing monitoring and assessment to allow for suitable adjustments along the way. Is China on track towards primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model under the status quo with increased privatisation of the hospital sector?

China's future health-care system under the status quo

Prospects of strong primary health care

Generally, primary health care in China is weak and its core functions in prevention, case detection and management, gatekeeping, referral, and care coordination—essential for non-communicable disease prevention and control—are not being met. For instance, findings from studies32, 33, 34 showed that only 30·1%34 of adults with diabetes and 41·632–57·4%33 of adults with hypertension were aware they had the conditions. Few patients aware of their conditions receive treatment. Only 25·8%34 patients with diabetes, 34·432–49·0%33 of patients with hypertension, and 8%35 of patients with mental health problems get treated; in patients with diabetes and hypertension who do get treated, less than half32, 33, 34 get their condition under control.32, 33, 34, 35 An international study32 showed that the awareness, treatment, and control rates for hypertension were 41·6%, 34·4%, and 23·8%, respectively in China, compared with 52·5%, 48·3%, and 32·3% in the upper-middle income countries in the study. Furthermore, admission rates for complications from diabetes in China are more than five times the rate in countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, a sign of poor primary health care.14

A major challenge is how to transform primary health care delivery from an approach based on patients and episodes to a population-based approach. Increased funding and infrastructure, building are necessary, but not sufficient to bring about this transformation. A reformed medical education curriculum and other innovative programmes to train a new cadre of modern primary health-care providers are needed.36 However, how long this will take is unclear.

Barriers for integration of primary health care with hospital-based secondary or tertiary care

Primary health-care centres and hospitals in China operate independently and compete for patients. We predict that this situation will persist for several reasons. First, providers of all facility levels are mainly paid by fee-for-service, creating incentives to increase activities rather than improve patient health. Providers have no incentive to coordinate care with other health-care professionals because their financial interest is to keep rather than refer patients to an appropriate site of treatment. The government has announced a shift from fee-for-service to other forms of provider payment, such as case-based payments, capitation, and global budget. However, they have so far been implemented as facility-specific rather than population-based payments, and therefore, do not provide incentives for several providers to coordinate care decisions. Second, fragmentation in finance creates barriers for the integration of services. Although primary health-care providers are mostly financed by government subsidies to provide primary care, hospitals are paid by SHIs and patient out-of-pocket payments. Primary health-care facilities have no financial leverage over hospitals. Third, in many cases SHI coverage is more generous for inpatient than outpatient services, incentivising patients to seek hospital care first because, generally, patients do not trust the quality of primary health-care facilities. All these factors make it difficult for primary health care to have a gatekeeping role. Exacerbation of this situation means that, within the medical profession, specialists are held in high esteem, whereas primary health-care providers are not well respected, creating further barriers for them to have the care-coordinator role. Perhaps the greatest barrier to a primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model approach is the dominant profit-driven hospital sector, irrespective of whether the hospital is public or private.

China is starting to pilot some models of integrated care (panel 2 ). Because these pilots are ongoing, no assessment has been done yet. Instead, we compare features from the Chinese pilots with several facilitating characteristics that have emerged in reviewing of the international scientific literature about successful care integration. The most common features include provider and patient incentives, decision support for providers, information communication technology, and a clearly defined role for primary health care (table 2 ). Although these pilots score well in movement towards an integrated health information system, they generally do not have appropriate providers and patient incentives and dedicated care coordinators. In fact, most Chinese pilots are led by tertiary hospitals and were set up to capture market share, with lower-level facilities agreeing to refer patients to them exclusively.

Panel 2. Chinese pilots of integrated care.

In 2005, Pudong district in Shanghai began to pilot the so-called 2 + 1 model, which integrates a secondary hospital with several community hospitals. Pioneered by the Waigaoqiao Medical Group,37 this model includes Shanghai number seven People's Hospital and four community health centres. Patients who obtain referrals from the community health centres can get fast-track appointments at the hospitals.

Another common model is 3 + 2 + 1, which includes tertiary hospitals, secondary hospitals, and community health centres. This model is usually set up by a tertiary hospital. In principle, the head of the board of the network is usually a director from the tertiary hospital. The tertiary hospital takes the main responsibility for definition of the roles and responsibilities of each level of provider in the network. There are no explicit care coordination functions in these models. This model was piloted by two medical groups in Shanghai in 2011—Ruijin-Luwan and Xinhua-Chongming. Ruijing Hospital and the Xinhua Hospital Chongming Branch are the tertiary hospitals at the core of this three-tiered integrated delivery system.38 They are supported by two secondary hospitals and several primary facilities. Around ten to 15 medical groups using the 3 + 2 + 1 model will be established in Shanghai and more than 20 in Beijing will be developed to cover the whole municipality.39, 40

Because many of these pilots started not long ago or are still in the planning phase, there is no concrete evidence to show the effect of hospital integration. However, problems are emerging, particularly because of the bi-directional nature of referrals—in practice, only referrals to higher level hospitals work because of the relatively low-quality of care in primary hospitals.

Table 2.

Facilitating characteristics for successful care integration and features from the Chinese pilots

| Description | Comments on Chinese models | |

|---|---|---|

| Defined population or health conditions covered by the programme | Fully integrated systems integrate primary and hospital care across an entire population. Disease management programmes attempt to do the same but focus on particular groups within the population that share certain characteristics, such as age, a common disease or condition, or a geographical area21, 41 | Most have defined population by geographical location but do not focus on a particular health condition38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45 |

| Provider payment incentives to coordinate care | Bundled payments encourage care coordination by allocation of a fixed fee to provide a full range of services for a defined population within a certain time period across providers at various facility levels Pay-for-performance components are also increasingly being used to reward or penalise primary care physicians for improved preventive care and chronic disease management17, 21, 22, 46, 47, 48, 49 |

Most pilots do not include provider payment change. According to Shanghai's government guidance, social insurance is supposed to pay an integrated delivery network a global budget that covers all the providers within the network. To what extent it has been implemented is unclear38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45 |

| Patient incentives | Tiered reimbursement structures, referrals for specialist services, approvals for expensive diagnostic tests, and insurance discounts for engagement in health promotion activities or registering with accredited integrated delivery organisations motivate consumers to access the health-care system in the most cost-effective way21, 41, 47 | For most pilots, there is no differential tiered reimbursement schedule from SHI specifically developed to incentivise patients to use primary health care In some models, reimbursement rates for referred cases are higher than for non-referred cases In most models, obtaining referrals from community health centres fast tracks patients for appointments at higher-level hospitals38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45 |

| Role of primary health care | In several countries, registration with general practitioners is compulsory or highly incentivised financially with primary care providers acting as gatekeepers to the wider health-care system Multispecialty medical groups are made up of doctors from a number of specialties who take on a budget to provide all or some of the services needed by the population that they serve Transitional care models redirect care from hospital settings back towards the community, shifting care from physicians towards more multidisciplinary teams that include nurses, therapists, and social care workers All service delivery setups include some kind of case management with primary health care at the centre17, 41, 47 |

Most pilots are set up with the purpose of reduction of overcrowding at tertiary hospitals by redirecting patients to a lower level of facilities. They are not set up for care-coordination according to clinical protocols In most cases, community centres are supposed to play the gatekeeping role. Whether this has been successfully implemented is not known Primary health-care providers do not seem to play a core role in care-coordination. In fact, most of the networks are led by tertiary hospitals38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45 |

| Decision support for providers | Peer review, standardised care protocols, cross-disciplinary interactions, and training increasingly broadens the scope of various health-care professionals to act as patient care coordinators26, 41, 46, 50 | There is no explicitly defined care coordinator for the full continuum of services for a patient and period of time across the health facilities within the group Higher-level facilities second experts to the next lower level for training Whether there are multidisciplinary team based practice is unclear38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45 |

| Health information system | The use of standardised electronic health records that are interoperable across provider institutions is common in high performance integrated systems21, 22, 25, 41 | All have realised the essential role of health information technology in integrated care systems. Some integrated care groups (eg, Ruijin-Luwan), have established medical information exchange platforms and participated in information exchange across providers and care settings38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45 |

| Enabling regulations | Regulation and changes in organisational infrastructure facilitating the clinical integration of providers are less common and need strong government leadership and support from health-care professionals. Often what is necessary is a relaxation of regulations that impede clinical integration41, 46, 48 | The integration between providers has been impeded by some nationwide regulations. For instance, the number of health facilities where a doctor can practice is regulated (eg, three affiliations per doctor), which means that doctors cannot practice in all health facilities within a network. Also, there are regulations about what drugs each level of facility can dispense. If a patient is referred down to a community centre for rehabilitation, the community centre might not have the medicine that the patient needs. Some pilots are attempting to relax these restrictions51, 52 |

SHI=social health insurance.

Poorly governed and profit-driven public hospitals

Unlike most public hospitals in the world, Chinese public hospitals are an embodiment of both government and market failures. On the one hand, they are governed by bureaucratic rules and subject to conflicting policies from the many ministries that govern them.2 Hospital directors and managerial staff are mostly government-appointed officials who are accountable to the government.53 They do not have any autonomy over hiring and firing decisions, which are restricted by rigid Civil Service Rules.54 On the other hand, public hospitals are motivated by profits and behave similarly to any other for-profit organisation. They have built-in incentives to prescribe excessive diagnostic tests and pharmaceuticals to earn profits for distribution to physicians and finance hospital expansion. Most public hospitals have to earn 90% of their revenue from services provided, with government direct subsidies making up the rest. Meanwhile, the government sets fee schedules with prices for office visits and hospital bed-days set below cost and the latest diagnostic and medical technologies set above cost. Providers are allowed to charge a 15% mark-up on drugs. Physicians are incentivised to prescribe drugs and tests that are not clinically needed because their bonuses are frequently tied to these revenues.55, 56, 57, 58, 59 For these same reasons, hospital managers race to introduce high-tech services and expensive imported drugs to boost revenues. In this way, many public facilities act as private entities, putting profit above patient welfare.60, 61 To compound the problem, pharmaceutical and medical equipment companies provide hospitals and physicians with benefits for prescription of their products. All these have resulted in the large share of health expenditure spent on drugs in China. In 2011, expenditure on drugs as a share of total health expenditure was 43% percent compared with an OECD average of 16%,62 and drug revenues accounted for 41·4% of total hospital revenues.6 Because physician staff are the residual claimants of profits in public hospitals, they are de facto shareholders of the public hospitals. Hence, public hospitals have neither the motivation nor the incentive to integrate care with primary health-care providers or make treatment decisions based on cost-effectiveness or population health maximisation criteria.

Dynamics between public–private hospital competition and their likely consequences

How would entrance of private hospitals affect the market dynamics? Although private hospitals are not new in China, their role in health-care provision has been small. In 2011, private hospitals accounted for just 10% of total hospital admissions.6 Most are either high-end specialist hospitals that cater to the expatriate community and rich Chinese or small-scale hospitals providing elective services, such as cosmetic surgery for the general population. To reach 20% of market share by 2015 would mean rapid expansion. The policy announcement has since attracted a flurry of interest from private investors.

Trends so far suggest that most new entrants are motivated by profit, most of whom are private hospital chains, pharmaceutical and medical device conglomerates, and real estate developers. Although strategies vary from targeting of provincial megacities to sub-provincial urban centres, the emphasis has been on wealthier locations with strong household purchasing power and public insurance schemes that are more likely to cover a wider range of services.63 Investors describe a two-pronged strategy—targeting of high-end specialist hospitals that command high prices and buying of general public hospitals, typically contracted by SHI programmes, to maximise sale volume.64 Although some investors are building their own facilities, increasingly they enter the market by buying existing hospitals so they can take over existing land and staff. Various joint ventures also seek prestige by association with brand-name medical universities (appendix).

The existing scientific literature about the effect of market competition on hospital efficiency and quality has yielded mixed results depending on the institutional context.65, 66 With few exceptions, most published work does not examine competition between different ownership types. Investigators from a few studies noted that the presence of for-profit private hospitals led to a positive spillover effect on public hospital efficiency,67, 68 whereas in others, it led to public hospitals bearing a bigger share of severely ill patients because for-profit private hospitals limit their treatment to patients who are less severely ill69 (appendix). Reviews comparing quality and cost of care of hospitals with different ownership status have generally showed that for-profit status is associated with higher costs and lower (or similar) quality than private non-profits, but the degree varies by studies’ data sources, time periods, and regions covered.70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76 Evidence in the management literature suggests that for-profit private hospitals are more efficient in management and that competition can lead to improvements in management efficiency gains.77, 78 However, in the case of China, if public hospitals continue to be subject to bureaucratic governance, competition will unlikely translate to improvements in management.

Public–private hospital competition in China is more akin to competition between for-profit hospitals. We speculate that private for-profit hospitals entering the market would compete with established public hospitals offering higher compensation to attract the best public sector physicians, and acquiring the latest expensive high-tech equipment to signal a higher quality of health care. The higher costs would be passed onto patients or SHI programmes. In response, public hospitals would have to raise the salaries of their own medical staff and enter the medical arms race, further detracting from a primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model approach.

This scenario predicts that entrance of private hospitals might exacerbate the excessive use of high-tech diagnostic tests and expensive pharmaceutical products so long as they generate profits, especially because patients are often unable to judge clinical quality of care. If the parent company of a private hospital were a pharmaceutical or medical device firm, incentives to overprescribe would be even more reinforced.79 As the 12th FYP has identified the biomedical industry as one of the seven strategic industries for stimulation of the economy, both pharmaceutical and medical device companies are making aggressive moves into China's market.80

Although the government introduced a Certificate of Need policy in 2005 to regulate the purchase of expensive medical equipment,81 it has not been enforced effectively. A study in four Chinese cities showed that the number of CTs and MRIs increased by 50% on average between 2006 and 2009.82, 83, 84, 85, 86

Overall, our assessment suggests that China's prospect of provision of affordable and equitable access to health care with a primary health-care-centred integrated delivery model approach would be relatively dismal. The for-profit motive of large public hospitals would result in escalation of health-care cost, inefficient use of pharmaceutical and high-tech diagnostic tests, and an absence of incentives for public hospitals to integrate care with primary health-care facilities. Entrance of private investment will further exacerbate these trends. To remain solvent, insurance programmes might limit payments, reduce resources for primary health-care services, and pass the higher costs on to patients as out-of-pocket costs. A two-tier system would emerge, with rich people serviced by the for-profit private hospitals and another tier for the rest of the population, leading to unequal access to and quality of care. In the long term, population health outcomes would suffer while the burden of rising health-care expenditures continues to increase.

A way forward towards an affordable, equitable, and effective health-care system

Adopt a systemtic approach

If the status quo does not lead China towards affordable, equitable, and effective health care for its people, what alternative pathway could it consider? In this section, we propose a way forward, taking into account what China has already embarked on, what is feasible in view of existing institutional constraints, and supplemented by international experience. We take as a starting point that the government will continue to fund basic health care, mainly through SHI, with some direct funding to primary health-care facilities and that it is highly unlikely that the government will reverse course to directly pay hospitals from government budgets; and that the for-profit private hospital market share will continue to grow as a result of government policies and increased demand from a population with rising income. Therefore, the question is how to introduce systemic changes that would make the best use of these conditions, bearing in mind ongoing reform efforts described in table 1.

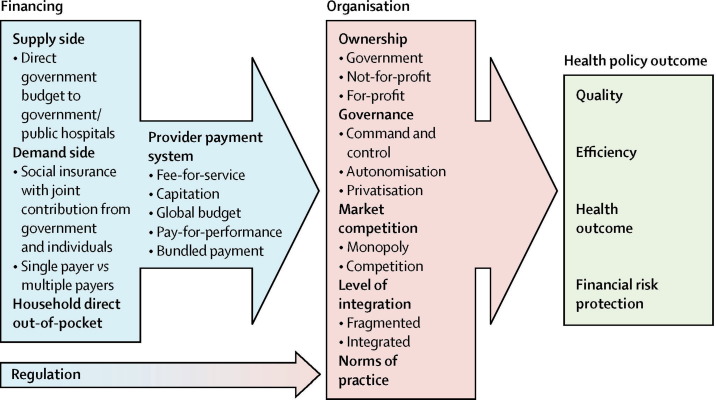

Figure 1 shows the systemic framework followed in our proposal. We first discuss what the government might do to improve the organisation of health-care delivery and then how financing and provider payment incentives could be used to further enhance improvements of delivery. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the various policy levers that could affect health-care delivery decisions, either independently or in combination with one another. The organisational features of the health sector—such as ownership, governance, market competition, level of integration, and norms of practice—all affect health-care delivery practices. Additionally, how health care is financed and how providers are paid substantially affects treatment decisions because they create different incentives for providers. Regulation could also be used, but its effect is often dampened by poor enforcement.

Figure 1.

A schematic framework relating various policy levers to health-care delivery

table 3 provides a brief description of the financing, key organisational features, and provider payment methods used by selected Asian countries to put our proposal in the global context.

Table 3.

Snapshot of health-care systems in selected Asian countries

| Hong Kong | Taiwan | Singapore | Japan | South Korea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General description | Two-tiered system with the government directly funding public hospitals or clinics and the private sector financed by a mix of direct out-of-pocket payment and private insurance and primarily serving the higher-income and middle-income groups. A hospital sector dominated by public providers and a primary care sector dominated by private clinics creates a barrier for service integration. Quality of care in the private sector is poorly regulated and highly variable | The National Health Insurance (NHI) covers 100% of the population with comprehensive service coverage. As a single-payer system, it is quite effective in controlling of health expenditure growth and assurance of equal access, however, there are quality and efficiency weaknesses in service delivery | Covers all citizens through Medisave (an individual savings account), MediShield, Medisave-Approved Integrated Shield Plans, and Medifund; this system is inequitable because Medisave does not provide risk pooling. Medisave creates disincentives to use primary care because it can only pay for inpatient services and chronic disease related outpatient services | NHI covers 100% of the population with comprehensive service coverage. It uses a nationally uniform fee schedule and claims review to control cost. Professional governance and accountability are relatively weak in the service, and delivery and quality can be variable | NHI covers 100% of the population. Service coverage has been increased, although coinsurance is high. Fees-for services provide hospital with incentives to oversupply services that might not be clinically necessary, leading to expenditure growth and high out-of-pocket spending | |

| Total health expenditure as % of GDP | 5·1%87 | 6·6%88 | 4·7%89 | 10·1%89 | 7·5%89 | |

| Financing | ||||||

| Sources of financing (note: private includes out-of-pocket and private insurance) | Government 48·7%, private 51·3%87 |

Government 5·88%, NHI 52·24% (Government vs individual vs employer: 25·5% vs 38·0% vs 36·5%), private 36·74%, other 5·14%88 | Government 37·60%, private 62·40%90 |

Government 10·18%, -NHI 71·92%, -private 17·90%91 |

Government 11·17%, -NHI 43·26%, -private: 45·57%91 |

|

| Risk pooling | One risk pool for government financing; no risk pooling for private financing | One risk pool for NHI | One risk pool for Medishield; one risk pool for Medifund; no risk pooling for Medisave | Several risk pools for NHI but all use the same benefit package and fee schedule | One risk pool for NHI | |

| Provision | ||||||

| Public–private hospital share (beds) | Public 87·59%, private (mix of for-profit and not-for-profit): 12·41%87 |

Public 33·74%, private (mix of for profit and not for profit): 66·26%88 |

Public 85·59%, private (mainly for profit): 14·41%92 |

Public 26·34%, private (mainly not for profit): 73·66%91 |

Public 12·44%, private (not for profit by law, but for profit in behaviour) 87·56%91 |

|

| Public–private competition | Public and private hospitals compete on the margin on personal aspects of quality—eg, waiting time, choice of doctors, and hotel services | NHI purchases care from public and private sectors on equal terms | Public hospitals have three classes of ward with differentiated government subsidies. Private ward has no subsidy and compete directly with private hospitals. Patients have free choice of wards | NHI purchases care from public and private sectors on equal terms | NHI purchases care from public and private sectors on equal terms | |

| Governance of public hospitals | Corporatised and managed by the Hospital Authority | Public hospitals are becoming more autonomous in planning and delivery of services, although approval is needed from the Department of Health; public hospitals can manage their own staff except for civil servants | Public hospitals are corporatised and managed autonomously. They are managed similarly to not-for-profit organisations and subject to broad policy guidance by the Government through the Ministry of Health | Mostly managed by municipal governments with some autonomy given to hospital directors | Most public hospitals have been corporatised. Ministry of Health and Welfare has taken the lead to streamline the governance structure of public hospitals by putting most under their jurisdiction | |

| Primary health care | Mostly provided by private doctors in individual practices (80%) with some limited government outpatient clinics targeting low-income neighbourhoods (20%). Low or non-existent gatekeeping | Most care is provided by privately operated clinics; the government also operates some health stations in the mountain and island areas. A family doctor plan was launched in March, 2003, to promote integrated primary care with referrals for more specialised treatment when needed |

Primary health care is provided in government outpatient polyclinics (20%) and private medical practitioner's clinics (80%) | Clinics, mainly owned by physicians or medical corporations (and some by the national and local governments), provide primary care and specialist care | No clear demarcation between primary and secondary care and most clinical practitioners are also specialists who often do not do the functions of what might conventionally be viewed as primary-care practice. Low or non-existent gatekeeping | |

| Provider payment methods | Public: direct government budgets make up the bulk (>80%) of revenue, user fees (heavily subsidised at 80–90%) make up the rest. Private: fee-for-service with providers setting their own fees |

Fee-for-service with global budgets, supplemented by diagnosis-related groups and pay-for-performance for selected number of conditions | Public: direct government budgets and charging fees; fees for private wards are not subsidised, whereas fees for open wards are subsidised at about 80%. Private: fee-for-service with providers setting their own fees |

Fee-for-service, with all the different insurance schemes following one fee schedule set nationally | Predominantly fee-for-service with one national fee schedule, with intention to move towards diagnosis-related groups and capitation, but progress has been slow | |

GDP=gross domestic product. NHI=national health insurance.

Improve the organisation of health-care delivery

We propose that the government establish benchmark competition (a combination of norms and market forces) between public and private hospitals, with companion policies to reform the governance of public hospitals.

First, the government would need to re-create exemplary models of public hospitals to serve as the benchmark. This is consistent with already announced government directives clarifying the role and objective of public hospitals to pursue the public interest93, 94 defined as “making the most efficient use of available public resources to maximize the benefits for the people—providing equal, accessible and quality healthcare to everyone”.95

To achieve this objective, a new accountability system needs to be established to hold public hospitals accountable for delivery of cost-effective services on an equitable basis. To promote public hospitals to coordinate with primary health care, assessment can be based on a set of indicators that emphasises population-based prevention and management, quality of care, service provision to poor people, and patient satisfaction. Similar to the Hospital Foundation Trusts in England96, 97, 98 and public hospitals in Hong Kong,99 a board should be set up to which public hospitals are accountable to. Unlike existing boards in China, which mainly consist of government officials, they should be made up of representatives from local communities. Public hospitals would produce a quality report together with financial statements on a quarterly basis for external audit and review. Hospitals that perform well would be publicly honoured and receive bonuses for their dedication to serving patient interests. Additionally, to improve efficiency, the government should revamp the governance of public hospitals by giving hospital directors the autonomy to hire and fire staff based on performance and to set up compensation and incentive schemes within their hospitals to align the staff's incentives to pursue the public interest.

Physicians should be paid a reasonable salary with the ability to earn extra bonuses based on the quality of care provided rather than the revenue generated, thus removing compensation from behaviour in prescription of drugs. This new scheme must be accompanied by a revision of the fee schedule that covers the cost of health services, removing the need to use profit-making drugs and high-tech diagnostic tests as compensation for lost revenue. To do this, China needs to establish a standardised cost accounting system in all public hospitals.

Making these changes would be challenging. The government could consider selecting the most prestigious tertiary public hospital in all major cities to act as standard bearers in improvement of their governance structure, their management, and ultimately their performance. They would become the benchmark for other public hospitals to emulate. This strategy has already been used by Singapore. The Chinese Government is already advancing some of these policies and if further developed and appropriately implemented, we predict that in 10–15 years China would be able to establish at least one flagship public hospital as a benchmark in each geographical market against which both public and private hospitals could compete. In the future, when not-for-profit private hospitals enter with the objective to pursue the public interest, the government could also work with them to establish them as flagships.

Use of financing and provider payment incentives to enhance delivery reform

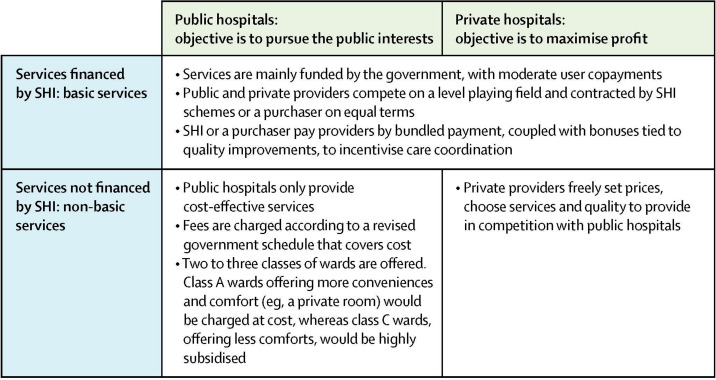

Hospital services in China can be conceptualised as two markets (figure 2 ). The first, mainly funded by the government through SHI, would provide basic health care. The second, mainly funded by direct out-of-pocket payment and some private insurance, would consist of higher-end services (non-basic services). We anticipate that this market would increase over time with continuous technological advancements, rising consumer expectations for higher-end services, and a possibly slower rate of increase of government funding for health care as growth in GDP moderates. Public and private provision would coexist, although the private sector would largely be concentrated in urban areas providing hospital services.

Figure 2.

Two hospital service markets

SHI=social health insurance.

For basic services, both public and private hospitals (should they choose to enter the market) would be financed mainly by SHI schemes. The government should continue to increase funding for these services at an annual rate at least commensurate with GDP growth. The three SHI schemes would integrate, according to government plans, and be managed by one agency acting as a purchaser. International experience has shown that the more integrated the payers (or SHI schemes in this case), the more leverage they have to make changes in the delivery system. Canada, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea all have single-payer systems that have shown their ability to control health expenditure growth (table 3 ). In addition to integration, SHI would gradually become a more strategic purchaser. Chinese SHI's main objective is to balance costs with little concern for quality of care. The Ministry of Finance, as the financier, should hold the purchaser accountable for the quality of care that they purchase for their enrolees.

This purchaser should contract public and private providers on equal terms, as is practised in other systems with universal health insurance, such as Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, and Canada (table 3). The purchaser should move from paying hospitals by fee-for-service to population-based capitation payment, an all-inclusive payment per person, per year, for a defined and comprehensive scope of services. This form of bundled payment should provide incentives to contain costs, reduce unnecessary services, and encourage integration and coordination of services.100 The payment will cover services that span across primary, secondary, and tertiary care. In the long-term when primary health-care facilities have developed their capacity, they could act as a budget holder and take primary responsibility as care coordinators. However, secondary level hospitals (equivalent to district hospitals elsewhere) could initially play this part because most primary health-care facilities in China might not have the necessary technical or managerial capacities initially. This method could be coupled with pay-for-performance, meaning that providers’ compensations are tied to quality or patient outcomes. Evidence for performance-based payment is emerging, with their effectiveness dependent on designs and organisational contexts.101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107

With population-based capitation, hospitals would find it in their financial interest to invest in health promotion and prevention, incorporate and coordinate with primary health-care facilities, and strengthen their functions within a multidisciplinary delivery setting as cost-saving strategies.

For non-basic services, which patients pay for directly out-of-pocket, the key question is how to improve efficiency through competition while maintaining equity. Public hospitals would charge patients fees according to the government fee schedule (revised to cover actual costs) while private hospitals set their own prices subject to government regulation. However, to ensure that patients with a low income are able to afford these non-basic services, hospitals would offer two or three classes of wards, from which patients could freely choose. Services in different wards would differ only in amenities and waiting time for elective procedures, but not clinical quality. Patients in all wards would be treated by the same team of physicians. Similar to the Singaporean model, class A wards offering more conveniences (eg, a private room) would be charged at cost, whereas class C wards offering less comforts would be subsidised at a much higher percentage of cost to assure equal clinical quality of treatment.108, 109

Continue to strengthen primary health care

Needless to say, the government should continue its ongoing reform to strengthen primary health care, and fund and provide traditional public goods such as clean water, sanitation, and vector control, for which the private sector will neither fund nor provide. Additionally, for effective prevention and control of non-communicable diseases, the government should develop a multisectoral strategy that includes both targeted high-risk group identification and population-wide interventions aimed at reduction of risk factors such as obesity, tobacco use, and sedentariness.

Finally, we suggest that China allows civil society and community-based non-governmental organisations to complement public primary health-care providers in areas where the public sector is weak—eg, social services and home care for elderly people. Community-based organisations have been effective in the delivery of services in rural and poorer communities in low-income countries.110

Conclusions

China's pledge to provide affordable, equitable access to quality basic health care for all its citizens is laudable, and present reforms have laid important foundations. However, substantial challenges in the reform of its delivery system, together with a new policy to promote private hospitals could derail China from achievement of its goals. The challenges that it faces are complex and there is no stand-alone policy that would provide the magic bullet. We suggest a systemic approach that integrates benchmark competition, improved public hospital accountability, stronger coordination across levels of care, and increased performance-based purchasing to leverage changes in health-care delivery towards a more cost-effective and high-quality system that serves the changing needs of China's population.

China is big and heterogeneous. Our recommendations are necessarily directional rather than operational. Each locale will have to modify and refine their specific models based on its conditions. Success will also depend on implementation conditions. The government should institutionalise objective monitoring and evaluation to support evidence-based mid-course adjustments. Particularly, China should assess how the entry of private hospitals affects its health-care system before it makes any decision to further expand their market share. Otherwise, China might not be able to rein in a runaway delivery system plagued with inequity and cost escalation.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Our analysis is based on a review of published scientific literature. We undertook three main scientific literature searches for on the effect of hospital competition, ownership, and integrated or coordinated care. Search terms used included “hospital competition”, “hospital ownership”, “public hospital”, “private hospital”, “not-for-profit hospital”, “integrated care”, “coordinated care”, and “disease management programs” combined with “cost” or “expenditure” or “health outcome” or “quality”. We limited results to articles, book chapters, or reports classified as reviews. We excluded earlier reviews that were included in more recent papers. For subjects of which no reviews exist, we also reviewed individual studies. Database searches include PubMed, journal storage (JSTOR), Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar. For coordinated or integrated care, we also searched the websites of organisations such as the King's Fund, the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, the European Observatory, and the Commonwealth Fund. We further refined the results to chronic disease treatment or management. For descriptive reviews, we excluded reviews that included only one country. The search was complemented by references cited in relevant studies and suggestions from peer-reviewers. We included studies published between Jan 1, 1999 and June 17, 2014. For the examples of Chinese pilots of integrated care, we searched China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang for Chinese language papers using key words “yi lian ti” or “yi liao lian he ti” (in Chinese). Only papers in English and Chinese were used.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Reem Hafez and Wei Han for their excellent research assistance.

Contributors

WY and WCH both contributed to the overall conceptualisation and analysis plan. WY took main responsibility for analysis of the scientific literature, synthesising of the findings, and writing of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the recommendation sections and have seen and approved the final version.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.National Bureau of Statistics of China . China Statistical Yearbook. China Statistics Press; Beijing: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yip WC, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu S, Ma J, Maynard A. Early appraisal of China's huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet. 2012;379:833–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.People's Republic of China 12th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development. 2014. http://www.gov.cn/2011lh/content_1825838.htm (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 4.State Council People's Republic of China. The Twelfth Five-Year Plan for Health Sector Development. 2014. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2012-10/19/content_2246908.htm (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 5.State Council People's Republic of China. On Deepening Medical and Health System: Notice of the Work Arrangements. 2012. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2012-04/18/content_2115928.htm (accessed June 26, 2014).

- 6.Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China . China health statistical yearbook. China Union Medical University Press; Beijing: 2009–12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li K. Deepening Healthcare Reform for the benefit of all. http://www.qstheory.cn/zxdk/2011/201122/201111/t20111114_123642.htm (accessed Nov 14, 2011).

- 8.Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;379:805–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Development and Reform Commission. Ministry of Health. Ministry of Finance. Ministry of Commerce. Ministry of Human Resources. Social Security People's Republic of China. Further Encouraging and Guiding the Establishment of Medical Institutions by Social Capital. 2014. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2010-12/03/content_1759091.htm (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 10.National Health and Family Planning Commission. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine People's Republic of China. Accelerate the development of establishing hospitals with social capital. 2014. http://www.moh.gov.cn/tigs/s7846/201401/239ae12d249c4e38a5e2de457ee20253.shtml (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 11.Ministry of Health Development and management of private hospitals. 2014. http://wsb.moh.gov.cn/mohylfwjgs/s3586/201204/54509.shtml (accessed May 29, 2014).

- 12.Huang C, Hai Y, Koplan J. Can China diminish it's burden of non-communicable diseases and injuries by promoting health in its policies, practices, and incentives? Lancet. 2014;384:783–792. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong P, Liang S, Carlton EJ. Urbanisation and health in China. Lancet. 2012;379:843–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61878-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Marquez P, Langenbrunner J. Toward a healthy and harmonious life in China: stemming the rising tide of non-communicable diseases: human development unit. The World Bank; East Asia and Pacific Region: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang G, Kong L, Zhao W. Emergence of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Lancet. 2008;372:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381:1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curry N, Ham C. Clinical and service integration: the route to improved outcomes. The King's Fund; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh D, Ham C. Improving care for people with long term conditions: a review of UK and international frameworks. 2006. http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/downloads/review_of_international_frameworks__chris_hamm.pdf (accessed June 26, 2014).

- 19.Goodwin N, Dixon A, Anderson G, Wodchis W. Providing integrated care for older people with complex needs: lessons from seven international case studies. The King's Fund; London: 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ham C, Curry N. Integrated care: What is it? Does it work? What does it mean for the NHS? London The King's Fund, 2011.

- 21.OECD . Value for money in health spending. Organisation for economic cooperation and development; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy D, Mueller K, Wrenn J. Kaiser Permanente: Bridging the quality divide with integrated practice, group accountability, and health information technology. The Commonwealth Fund pub; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chumbler NR, Neugaard B, Kobb R, Ryan P, Qin H, Joo Y. Evaluation of a care coordination/home-telehealth program for veterans with diabetes: health services utilization and health-related quality of life. Eval Health Professions. 2005;28:464–478. doi: 10.1177/0163278705281079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: implementing patient-centered medical homes in the nation's largest intergrated delivery system. The Commonwealth Fund; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald K, Sundaram V, Bravata D. Care Coordination. In: Shojania K, McDonald K, Wachter R, Owens D, editors. Closing the quality gap: a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ofman JJ, Badamgarav E, Henning JM. Does disease management improve clinical and economic outcomes in patients with chronic diseases? A systematic review. Am J Med. 2004;117:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Göhler A, Januzzi JL, Worrell SS. A systematic meta-analysis of the efficacy and heterogeneity of disease management programs in congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12:554–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruis AL, Smidt N, Assendelft WJ. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009437.pub2. CD009437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dudley L, Garner P. Strategies for integrating primary health services in low- and middle-income countries at the point of delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003318.pub3. CD003318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nolte E, Pitchforth E. What is the evidence on the economic impacts of integrated care?: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2014.

- 32.Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA. 2013;310:959–968. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.184182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng X, Pang M, Beard J. Health system strengthening and hypertension awareness, treatment and control: data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Bull World Health Org. 2014;92:29–41. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.124495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Y, Wang L, He J. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA. 2013;310:948–959. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.168118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2009;373:2041–2053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou Jianlin, Michaud Catherine, Li Zhihui. Transforming the Education of Health Professionals in China: Progress and Challenges. Lancet. 2014;384:819–827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dan S, Zhang G. The practice and discussion of medical resources integration in Shanghai Waigaoqiao District, Pudong New Area. Chinese Health Resour. 2011;14:325–326. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ministry of Health People's Republic of China. Briefing on public hospital reform no.316: the case of Shanghai. 2013. http://www.moh.gov.cn/yzygj/s10006/201305/4fcc8e649ded4a07b78f1982f7d21a56.shtml (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 39.Ministry of Health People's Republic of China. Briefing on public hospital reform no.302: the case of Beijing. 2013. http://www.moh.gov.cn/tigs/s3582/201303/b83022b55d40411cb068998332ae64ae.shtml (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 40.Shen X, Ding H, Zhang K, Fu C. Healthcare alliance through vertically integrating resources: an endeavor in Shanghai, China. Chinese J Evidence-Based Med. 2013;13:527–530. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shih A, Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Gauthier A, Nuzum R, McCarthy D. Organizing the U.S. health care delivery system for high performance: The Commonwealth Fund commission on a high performance health system. The Commonwealth Fund; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beijing Municipal Health Bureau The guidance on integrated care network. 2013. http://zhengwu.beijing.gov.cn/gzdt/gggs/t1332793.htm (accessed May 29, 2014).

- 43.Chaoyang District Health Bureau The implementation plan on developing integrated care network. 2013. http://wsj.bjchy.gov.cn/root/cywsj/tzgg/231709.htm (accessed May 29, 2014).

- 44.Government of Pudong People's Republic of China. The Twelfth Five-Year Plan for Health Sector Development of Pudong. http://gov.pudong.gov.cn/govOpen_GFZH1/Info/Detail_420959.htm (accessed March 30, 2014).

- 45.Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau The guidance on integrated care network. 2010. http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/shanghai/node2314/node2319/node12344/userobject26ai23662.html (accessed May 29, 2014).

- 46.Hofmarcher MM, Oxley H, Rusticelli E. Improved health system performance through better care coordination: OECD Health Working Paper no30. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paris V, Devaux M, Wei L. Health Systems Institutional Characteristics: A survey of 29 OECD Countries: OECD Health Working Papers no. 50. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shortell S, Addicott R, Walsh N, Ham C. Accountable care organisations in the United States and England: testing, evaluating and learning what works. The King's Fund; London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Struijs JN, Baan CA. Integrating care through bundled payments—lessons from the Netherlands. NEJM. 2011;364:990–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouwens M, Wollersheim H, Hermens R, Hulscher M, Grol R. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:141–146. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kong L. Shanghai: beautiful idea encountered institutional barriers. Health Newspaper. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu F, Gao W, Ma J, Lin J, Hu Y. Practice and thought of Ruijin-Luwan Health Alliance under the new health care reform. Chinese Hosp Manage. 2013;33:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allen P, Cao Q, Wang H. Public hospital autonomy in China in an international context. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;29:141–159. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li W. Reform and governance for public hospitals. Jiangsu Soc Sci. 2006;5:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blumenthal D, Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents—the evolving Chinese health care system. NEJM. 2005;353:1165–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Xu J, Wang F. Overprescribing in China, driven by financial incentives, results in very high use of antibiotics, injections, and corticosteroids. Health Aff. 2012;31:1075–1082. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu X, Mills A. Evaluating payment mechanisms: how can we measure unnecessary care? Health Policy Plan. 1999;14:409–413. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reynolds L, McKee M. Serve the people or close the sale? Profit-driven overuse of injections and infusions in China's market-based healthcare system. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2011;26:449–470. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yip WC-M, Hsiao W, Meng Q, Chen W, Sun X. Realignment of incentives for health-care providers in China. Lancet. 2010;375:1120–1130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He GX, van den Hof S, van der Werf MJ. Inappropriate Tuberculosis Treatment Regimens in Chinese Tuberculosis Hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:153–156. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ou Y, Jing B-Q, Guo F-F. Audits of the quality of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in Shandong Province, China, 2006 to 2011. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.OECD. WHO Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2012. 2012. http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/healthataglanceasiapacific2012.htm (accessed June 26, 2014).

- 63.He C. Hospital Investment Series IV: water in public hospitals is deep. 2014. http://companies.caixin.com/2014-01-22/100631802.html (accessed March 30, 2014).