Abstract

Rationale: Development of diagnostic tools with improved predictive value for tuberculosis (TB) is a global research priority.

Objectives: We evaluated whether implementing higher diagnostic thresholds than currently recommended for QuantiFERON Gold-in-Tube (QFT-GIT), T-SPOT.TB, and the tuberculin skin test (TST) might improve prediction of incident TB.

Methods: Follow-up of a UK cohort of 9,610 adult TB contacts and recent migrants was extended by relinkage to national TB surveillance records (median follow-up 4.7 yr). Incidence rates and rate ratios, sensitivities, specificities, and predictive values for incident TB were calculated according to ordinal strata for quantitative results of QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST (with adjustment for prior bacillus Calmette-Guérin [BCG] vaccination).

Measurements and Main Results: For all tests, incidence rates and rate ratios increased with the magnitude of the test result (P < 0.0001). Over 3 years’ follow-up, there was a modest increase in positive predictive value with the higher thresholds (3.0% for QFT-GIT ≥0.35 IU/ml vs. 3.6% for ≥4.00 IU/ml; 3.4% for T-SPOT.TB ≥5 spots vs. 5.0% for ≥50 spots; and 3.1% for BCG-adjusted TST ≥5 mm vs. 4.3% for ≥15 mm). As thresholds increased, sensitivity to detect incident TB waned for all tests (61.0% for QFT-GIT ≥0.35 IU/ml vs. 23.2% for ≥4.00 IU/ml; 65.4% for T-SPOT.TB ≥5 spots vs. 27.2% for ≥50 spots; 69.7% for BCG-adjusted TST ≥5 mm vs. 28.1% for ≥15 mm).

Conclusions: Implementation of higher thresholds for QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST modestly increases positive predictive value for incident TB, but markedly reduces sensitivity. Novel biomarkers or validated multivariable risk algorithms are required to improve prediction of incident TB.

Keywords: latent tuberculosis, epidemiology, screening, QuantiFERON, T-SPOT.TB

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Few studies have previously assessed the association between quantitative IFN-γ release assay results and tuberculosis (TB) incidence rates; all were restricted to only one test, the QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube (QFT-GIT). Although two studies have suggested that a QFT-GIT threshold of ≥4 IU/ml may improve prediction of incident TB, none were able to fully assess the potential impact of implementing higher thresholds on predictive values, or the proportion of incident cases missed by latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) screening programs.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This is the first study to comprehensively assess the potential impact of implementing higher diagnostic thresholds for all three available LTBI tests (tuberculin skin test, QFT-GIT, and T-SPOT.TB). We demonstrate that TB incidence rates increase incrementally with the magnitude of the T-cell recall response for all three tests. However, although implementing higher thresholds leads to modest improvement in positive predictive value of these tests for incident TB, this benefit is offset by a marked loss in sensitivity, with the majority of incident TB cases being missed. Implementing higher diagnostic thresholds for the tuberculin skin test and commercial IFN-γ release assays is therefore unlikely to be of value for LTBI-screening programs in settings aiming toward TB elimination.

Treatment for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) reduces the risk of progression to tuberculosis (TB) disease and thus offers an opportunity to prevent TB-related morbidity, while also interrupting onward transmission (1). Scaling up testing and treatment for LTBI among TB risk groups is therefore an integral component of the World Health Organization (WHO) End TB Strategy (2, 3). However, the effectiveness of LTBI-screening programs is undermined by the poor positive predictive value of currently available LTBI diagnostic tests for incident TB disease, which is <5% for both the tuberculin skin test (TST) and commercial IFN-γ release assays (IGRAs) over a 2-year period (4–6). As a result, the majority of individuals with a positive TST or IGRA will never develop TB disease. This leads to a large burden of unnecessary LTBI treatment, with associated risks of drug toxicity to patients, and economic costs to health services. Furthermore, poor predictive value may also undermine the uptake of LTBI treatment among target groups because of the low perceived risk of TB (7). The WHO has therefore highlighted the development of novel biomarkers with better predictive value as a key research and development priority in a target product profile (TPP) consensus document, stating optimal performance criteria of sensitivity and specificity ≥90% over a 2-year interval (8).

Recent emerging data from studies in both adults and infants in low– and high–TB-incidence settings have demonstrated that higher quantitative IGRA results are associated with increased risk of incident TB, thus raising hope that IGRAs themselves may go some way to fulfilling the WHO TPP (9–11). Moreover, because current diagnostic thresholds for scoring a positive test are based on detecting sensitization to Mycobacterium tuberculosis rather than development of incident TB disease, optimizing these thresholds might lead to improved implementation of existing LTBI diagnostics, while novel biomarkers with improved predictive value are awaited. However, previous evaluations of quantitative IGRA results have been limited to the QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube (QFT-GIT) assay only (9–13), and it remains unclear whether implementation of a higher threshold for positivity may actually be of use in clinical practice to improve the risk-stratification of patients with LTBI.

We sought to address these key knowledge gaps by extending follow-up of participants in the UK PREDICT (UK Prognostic Evaluation of Diagnostic IGRAs Consortium) TB study (6). First, we aimed to test the hypothesis that higher quantitative QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST results were associated with increased risk of incident TB. Second, we sought to evaluate the test sensitivities, specificities, and predictive values when higher thresholds for a positive test than currently recommended are used over a fixed 3-year follow-up period. Finally, we plotted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for all three tests to compare performance across the full range of test cutoffs. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (14).

Methods

Population

The UK PREDICT study cohort has been described in detail previously (6). Briefly, individuals aged ≥16 years were recruited (May 1, 2010 to June 30, 2015) from London, Birmingham, and Leicester. Inclusion criteria were recent contacts of patients with active TB; or recent migrants from, or prolonged travelers to, high–TB-burden countries. Participants treated for LTBI were excluded, as were participants diagnosed with suspected baseline prevalent TB (evidence of TB within 21 d of enrollment).

Study Procedures

Participants were tested with QFT-GIT (Qiagen), T-SPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec), and then Mantoux TST (Statens Serum Institut) using standardized protocols on the same day, at least 6 weeks from last TB exposure or migration. Indeterminate results were classified as recommended by the manufacturers (online supplement). Incident TB cases were identified via telephone interview at 12 and 24 months, and by linkage to the national TB surveillance system held at Public Health England, which includes all statutory TB notifications and all results of positive M. tuberculosis cultures. For this analysis, all participants were relinked to national TB surveillance records to identify individuals notified with TB until December 31, 2017. Follow-up was censored on the earliest of date of TB diagnosis, death, or December 31, 2017. The study procedures and protocol were approved by the Brent National Health Service Research Ethics Committee (10/H0717/14).

Statistical Analysis

Tuberculosis incidence rates and ratios were calculated relative to the negative test category (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) using Poisson models, according to ordinal strata for quantitative results of each LTBI test during the full duration of follow-up. For participants with previous bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination (defined by self-report and scar inspection), 10 mm was subtracted from the quantitative TST result to adjust for the associated sensitization to BCG (“BCG-adjusted TST”). The rationale for this was that, in the main UK PREDICT analysis, a BCG-stratified TST cutoff of 5 mm in BCG-naive or 15 mm in vaccinated participants performed most similarly to IGRA (6). For QFT-GIT and BCG-adjusted TST, test strata were based on previous data (9, 10, 15–17). For QFT-GIT, these were TB antigen IFN-γ minus unstimulated control IFN-γ levels of <0.35, 0.35–0.69, 0.7–3.99, and ≥4.00 IU/ml. For BCG-adjusted TST, the strata used were <5, 5–9, 10–14, and ≥15 mm induration.

For T-SPOT.TB, no previous data were available to inform the test strata examined. We chose initial strata of spot counts in the maximal TB antigen panel minus the negative control of ≤4 and 5–7 spots, based on manufacturer test thresholds for borderline and positive results, and used restricted cubic spline models to investigate the nonlinear association between quantitative T-SPOT.TB results and incident TB risk (online supplement). Informed by visualization of these models, we defined further strata of spot counts in the maximal TB antigen panel minus the negative control of 8–49 and ≥50 spots (corresponding approximately to the top 5% of quantitative T-SPOT.TB results in the cohort).

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and ROC curves for incident TB over a fixed 3-year follow-up period were calculated at the corresponding thresholds for each stratum.

Seven sensitivity analyses were performed, as detailed in the online supplement. All analyses were performed using Stata version 15.

Results

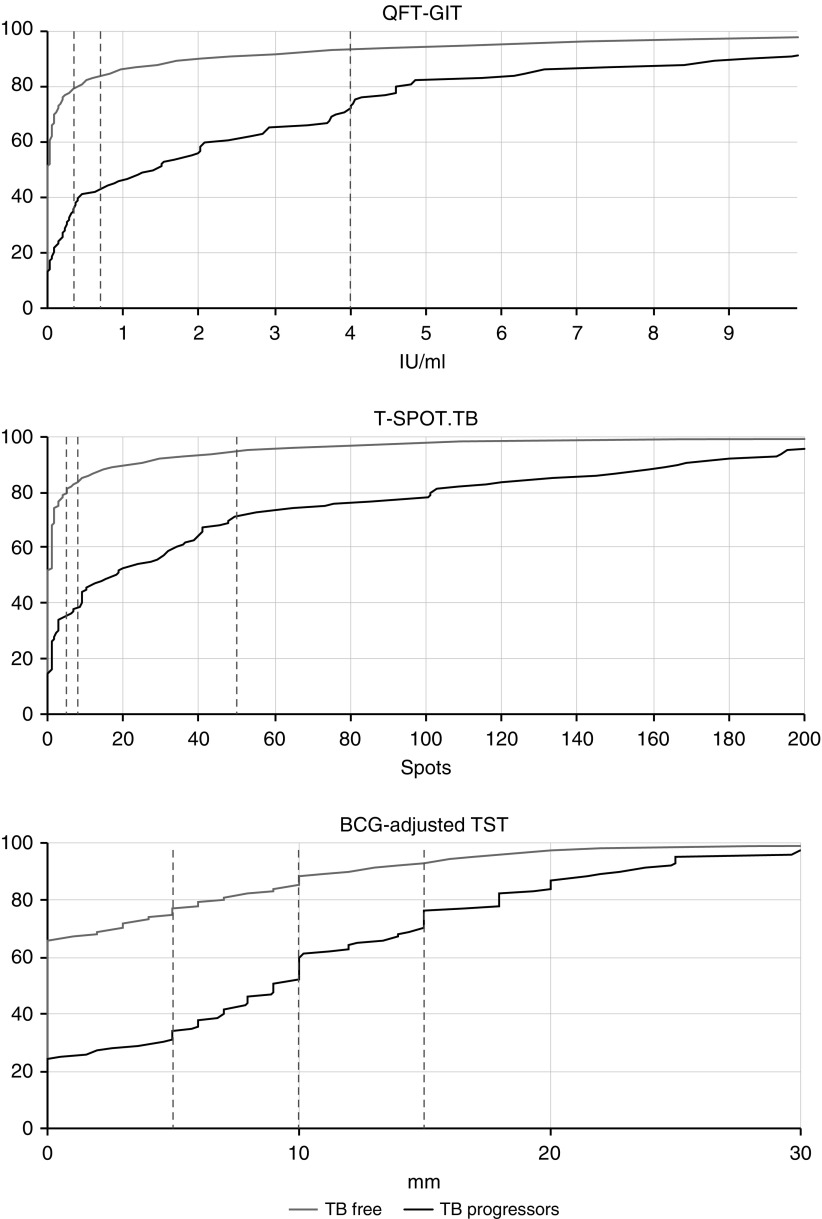

A total of 10,045 participants were recruited to the study. Of these, 175 had possible prevalent TB at baseline, and a further 260 were treated for LTBI. The remaining 9,610 were therefore included in the final study cohort, with median follow-up 4.7 years (interquartile range, 3.8–5.5). Baseline characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. A total of 5,526/9,610 (57.5%) participants were aged <35 years. The cohort included 4,781 (49.8%) recent TB contacts and 4,729 (49.2%) migrants from high-incidence countries, whereas 6,618/9,610 (68.9%) reported previous BCG vaccination. A total of 8,562 (89.1%), 8,079 (84.1%), and 7,833 (81.5%) of participants had available quantitative QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST results, respectively. A total of 107 participants progressed to incident TB during follow-up, of which 47 (43.9%) had pulmonary involvement, and 59 (55.1%) were microbiologically confirmed by either culture or PCR. Median time to TB disease among the progressors was 188 days (interquartile range, 76–488 d). A total of 71 (66.4%), 19 (17.8%), and 5 (4.7%) participants progressed during the first, second, and third years of follow-up, respectively. The distributions of quantitative QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and BCG-adjusted TST results, stratified by the development of incident TB, are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of UK PREDICT TB Cohort, Stratified by Whether or Not Participants Progressed to Incident TB during Follow-up

| TB Free | TB Progressors | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| M | 4,673 (49.2) | 56 (52.3) | 4,729 (49.2) |

| F | 4,758 (50.1) | 51 (47.7) | 4,809 (50) |

| Missing | 72 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 72 (0.7) |

| Age, yr | |||

| ≤35 | 5,455 (57.4) | 71 (66.4) | 5,526 (57.5) |

| >35 | 4,026 (42.4) | 36 (33.6) | 4,062 (42.3) |

| Missing | 22 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 22 (0.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 33 (26–47) | 30 (26–39) | 33 (26–47) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Indian | 3,939 (41.5) | 42 (39.3) | 3,981 (41.4) |

| White | 1,161 (12.2) | 12 (11.2) | 1,173 (12.2) |

| Black African | 1,126 (11.8) | 12 (11.2) | 1,138 (11.8) |

| Mixed | 881 (9.3) | 11 (10.3) | 892 (9.3) |

| Pakistani | 891 (9.4) | 15 (14) | 906 (9.4) |

| Bangladeshi | 712 (7.5) | 4 (3.7) | 716 (7.5) |

| Black Caribbean | 237 (2.5) | 5 (4.7) | 242 (2.5) |

| Other | 315 (3.3) | 5 (4.7) | 320 (3.3) |

| Missing | 241 (2.5) | 1 (0.9) | 242 (2.5) |

| UK Born | |||

| No | 7,917 (83.3) | 91 (85) | 8,008 (83.3) |

| Yes | 1,536 (16.2) | 16 (15) | 1,552 (16.1) |

| Missing | 50 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 50 (0.5) |

| Contact or migrant | |||

| Contact | 4,711 (49.6) | 70 (65.4) | 4,781 (49.8) |

| Migrant | 4,692 (49.4) | 37 (34.6) | 4,729 (49.2) |

| Missing | 100 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) |

| BCG vaccinated | |||

| No | 1,457 (15.3) | 13 (12.1) | 1,470 (15.3) |

| Yes | 6,538 (68.8) | 80 (74.8) | 6,618 (68.9) |

| Missing | 1,508 (15.9) | 14 (13.1) | 1,522 (15.8) |

| QFT-GIT | |||

| <0.35 | 6,603 (69.5) | 34 (31.8) | 6,637 (69.1) |

| 0.35–0.69 | 398 (4.2) | 7 (6.5) | 405 (4.2) |

| 0.7–3.99 | 793 (8.3) | 27 (25.2) | 820 (8.5) |

| ≥4 | 552 (5.8) | 26 (24.3) | 578 (6) |

| Indeterminate | 119 (1.3) | 3 (2.8) | 122 (1.3) |

| Missing | 1,038 (10.9) | 10 (9.3) | 1,048 (10.9) |

| T-SPOT.TB | |||

| <5 | 6,257 (65.8) | 33 (30.8) | 6,290 (65.5) |

| 5–7 | 316 (3.3) | 3 (2.8) | 319 (3.3) |

| 8–49 | 876 (9.2) | 30 (28) | 906 (9.4) |

| ≥50 | 416 (4.4) | 27 (25.2) | 443 (4.6) |

| Indeterminate | 119 (1.3) | 2 (1.9) | 121 (1.3) |

| Missing | 1,519 (16) | 12 (11.2) | 1,531 (15.9) |

| BCG-adjusted TST, mm* | |||

| <5 | 5,739 (60.4) | 30 (28) | 5,769 (60) |

| 5–9 | 805 (8.5) | 22 (20.6) | 827 (8.6) |

| 10–14 | 612 (6.4) | 18 (16.8) | 630 (6.6) |

| ≥15 | 576 (6.1) | 31 (29) | 607 (6.3) |

| Missing | 1,771 (18.6) | 6 (5.6) | 1,777 (18.5) |

| Follow-up, yr | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4.69 (3.82–5.52) | 0.51 (0.21–1.34) | 4.68 (3.78–5.51) |

| Total | 9,503 | 107 | 9,610 |

Definition of abbreviations: BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; IQR = interquartile range; QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin test; UK PREDICT = UK Prognostic Evaluation of Diagnostic IFN-γ Release Assays Consortium.

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

For participants with previous BCG vaccination (defined by self-report and scar inspection), 10 mm was deducted from the quantitative TST result to adjust for the associated sensitization to BCG (“BCG-adjusted TST”).

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution plots showing distribution of quantitative test results for the QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube, T-SPOT.TB, and bacillus Calmette-Guérin–adjusted tuberculin skin test, stratified by whether participants progressed to incident TB during follow-up. Dashed lines indicate thresholds used in this analysis. BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Indeterminate results contributed 122/8,562 (1.4%) QFT-GIT results and 121/8,079 (1.5%) T-SPOT.TB results. Of those with available results, 6,637 (77.5%), 405 (4.7%), 820 (9.6%), and 578 (6.8%) had QFT-GIT results in the <0.35, 0.35–0.69, 0.7–3.99, and ≥4.00 IU/ml strata, respectively. For T-SPOT.TB, 6,290 (77.9%), 319 (3.9%), 906 (11.4%), and 443 (5.6%) of participants had results in the ≤4, 5–7, 8–49, and ≥50 spots strata, respectively. For BCG-adjusted TST, 5,769 (73.7%), 827 (10.6%), 630 (8.0%), and 607 (7.75%) had induration in the <5, 5–9, 10–14, and ≥15 mm strata, respectively. Duration of follow-up was similar between participants in different test strata (online supplement).

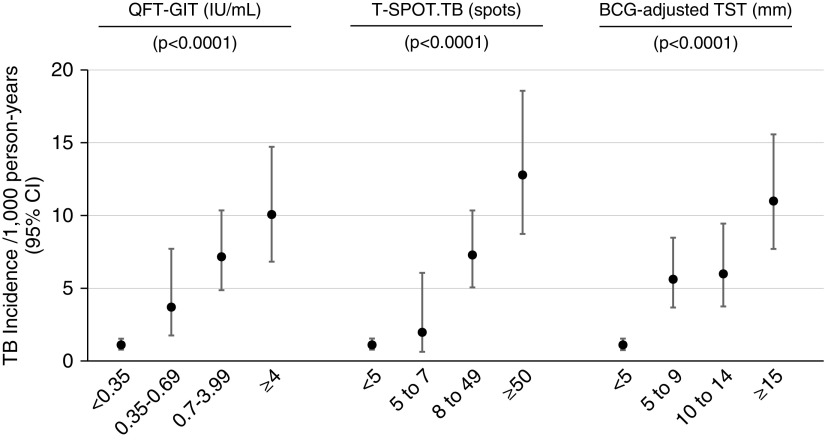

For all tests, TB incidence rates and ratios increased with the magnitude of the test response (Figure 2). For QFT-GIT, TB incidence rates (per 1,000 person-years) increased from 1.10 (95% CI, 0.78–1.53) in the <0.35 IU/ml stratum to 10.02 (6.82–14.72) in the ≥4.00 IU/ml stratum (likelihood ratio test for trend P < 0.0001). For T-SPOT.TB, TB incidence rates increased from 1.10 (0.78–1.54) in the ≤4 spots stratum to 12.73 (8.73–18.57) in the ≥50 spots stratum (P < 0.0001). For the BCG-adjusted TST, TB incidence rates increased from 1.07 (0.75–1.54) in the <5 mm stratum to 10.95 (7.70–15.57) in the ≥15 mm stratum (P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Tuberculosis incidence rates and ratios in ordinal strata for quantitative results of QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube, T-SPOT.TB, and bacillus Calmette-Guérin–adjusted tuberculin skin test. P values indicate likelihood ratio tests for trend. Data are also presented as a table in the online supplement. BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CI = confidence interval; QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Considering diagnostic test performance for the prediction of incident TB in the first 3 years of follow-up, positive predictive values (PPV) were uniformly low but increased modestly with the higher thresholds for all three tests (Table 2). PPVs were 3.0% (2.2–3.9) for QFT-GIT ≥0.35 IU/ml vs. 3.6% (2.2–5.5) for ≥4.00 IU/ml; 3.4% (2.6–4.4) for T-SPOT.TB ≥5 spots vs. 5.0% (3.2–7.5) for ≥50 spots; and 3.1% (2.4–4.0) for BCG-adjusted TST ≥5 mm vs. 4.3% (2.8–6.2) for ≥15 mm. However, as thresholds for test positivity increased, sensitivity declined for all tests (Table 2). For the QFT-GIT, sensitivity decreased from 61.0% (95% CI, 49.6–71.6) with a threshold ≥0.35–23.2% (14.6–33.8) with a threshold ≥4.00 IU/ml. For T-SPOT.TB, sensitivity decreased from 65.4% (54.0–75.7) with a threshold ≥5 spots to 27.2% (17.9–38.2) with a threshold ≥50 spots. For BCG-adjusted TST, sensitivity was 69.7% (59.0–79.0) with a threshold ≥5 mm but only 28.1% (19.1–38.6) with a threshold ≥15 mm.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Values, and Negative Predictive Values during 3 Years’ Follow-up with Prespecified Test Thresholds

| QFT-GIT (IU/ml) |

T-SPOT.TB (Spots) |

BCG-adjusted TST* (mm) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0.35 | ≥0.7 | ≥4 | ≥5 | ≥8 | ≥50 | ≥5 | ≥10 | ≥15 | |

| Sensitivity | |||||||||

| n | 50 | 44 | 19 | 53 | 50 | 22 | 62 | 42 | 25 |

| N | 82 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| Estimate, % | 61.0 | 53.7 | 23.2 | 65.4 | 61.7 | 27.2 | 69.7 | 47.2 | 28.1 |

| 95% CI | 49.6–71.6 | 42.3–64.7 | 14.6–33.8 | 54–75.7 | 50.3–72.3 | 17.9–38.2 | 59–79 | 36.5–58.1 | 19.1–38.6 |

| Specificity | |||||||||

| n | 6,134 | 6,511 | 7,242 | 5,856 | 6,155 | 6,948 | 5,520 | 6,295 | 6,882 |

| N | 7,755 | 7,755 | 7,755 | 7,363 | 7,363 | 7,363 | 7,445 | 7,445 | 7,445 |

| Estimate, % | 79.1 | 84.0 | 93.4 | 79.5 | 83.6 | 94.4 | 74.1 | 84.6 | 92.4 |

| 95% CI | 78.2–80 | 83.1–84.8 | 92.8–93.9 | 78.6–80.4 | 82.7–84.4 | 93.8–94.9 | 73.1–75.1 | 83.7–85.4 | 91.8–93 |

| Positive predictive value | |||||||||

| n | 50 | 44 | 19 | 53 | 50 | 22 | 62 | 42 | 25 |

| N | 1,671 | 1,288 | 532 | 1,560 | 1,258 | 437 | 1,987 | 1,192 | 588 |

| Estimate, % | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 4.3 |

| 95% CI | 2.2–3.9 | 2.5–4.6 | 2.2–5.5 | 2.6–4.4 | 3–5.2 | 3.2–7.5 | 2.4–4 | 2.6–4.7 | 2.8–6.2 |

| Negative predictive value | |||||||||

| n | 6,134 | 6,511 | 7,242 | 5,856 | 6,155 | 6,948 | 5,520 | 6,295 | 6,882 |

| N | 6,166 | 6,549 | 7,305 | 5,884 | 6,186 | 7,007 | 5,547 | 6,342 | 6,946 |

| Estimate, % | 99.5 | 99.4 | 99.1 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.2 | 99.5 | 99.3 | 99.1 |

| 95% CI | 99.3–99.6 | 99.2–99.6 | 98.9–99.3 | 99.3–99.7 | 99.3–99.7 | 98.9–99.4 | 99.3–99.7 | 99–99.5 | 98.8–99.3 |

Definition of abbreviations: BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CI = confidence interval; n = numerator; N = denominator; QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin test.

For participants with previous BCG vaccination (defined by self-report and scar inspection), 10 mm was deducted from the quantitative TST result to adjust for the associated sensitization to BCG (“BCG-adjusted TST”).

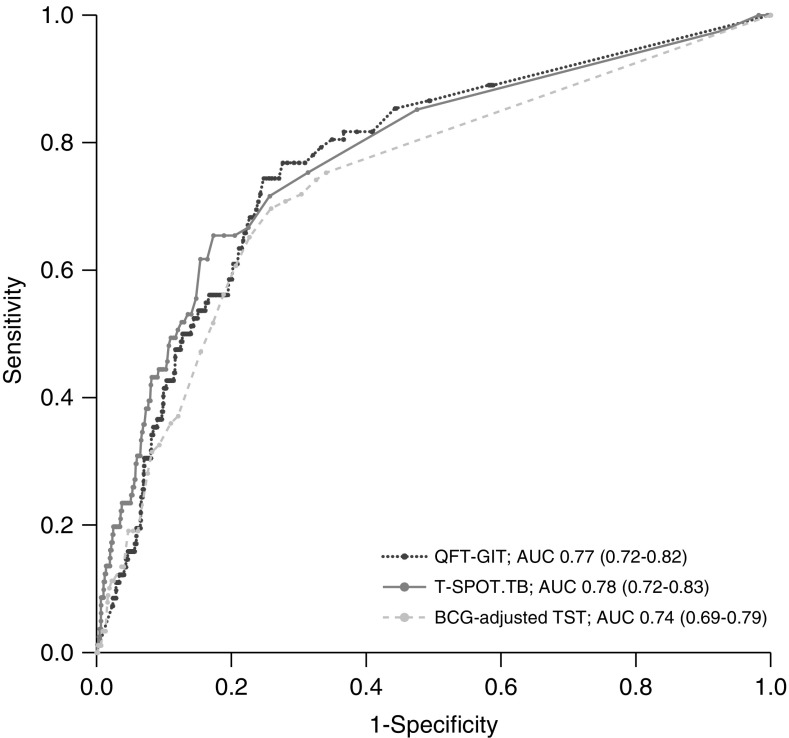

ROC curve analysis revealed similar areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROCs) of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.72–0.82), 0.78 (0.72–0.83), and 0.74 (0.69–0.79) for QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and BCG-adjusted TST for predicting incident TB over 3 years’ follow-up, respectively (Figure 3). Paired DeLong tests (18) revealed no difference in AUROCs for QFT-GIT (P = 0.21) or BCG-adjusted TST (P = 0.14), when compared with T-SPOT.TB.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for prediction of incident tuberculosis during 3 years’ follow-up by quantitative QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube, T-SPOT.TB, and bacillus Calmette-Guérin–adjusted tuberculin skin test results. The 95% confidence intervals are indicated in parentheses. AUC = area under the curve; BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; QFT-GIT = QuantiFERON Gold-In-Tube; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin test.

In the sensitivity analyses (online supplement), exclusion of incident TB cases <42 days from enrollment resulted in slightly lower TB incidence rates across all strata but had little impact on incidence rate ratios between strata. Similarly, the subanalyses restricted to TB contacts and migrants revealed lower TB incidence rates overall among migrants compared with TB contacts but little difference in incidence rate ratios between strata for each test. Analysis of participants with indeterminate results revealed only a small number of incident cases for both the QFT-GIT (n = 3) and T-SPOT.TB (n = 2), precluding further analysis. Inclusion of a fifth stratum for QFT-GIT (≥8 IU/ml) had no effect in increasing incidence rates further. Including fifth strata for T-SPOT.TB and BCG-adjusted TST (≥100 spots for T-SPOT.TB; ≥20 mm for BCG-adjusted TST) led to further increases in the incidence rates in these strata. However, as for the main analysis, there was a further loss of sensitivity when implementing corresponding diagnostic thresholds. Analysis of quantitative TST results without subtracting the 10-mm deduction for participants who reported BCG vaccination resulted in lower incidence rates in all strata, compared with the primary analysis, without changing the overall pattern observed. Limiting follow-up to 6 months produced similar sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value results to the main analysis. Finally, associations between quantitative test results and incident TB in multivariable Poisson models adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, country of birth, and indication for screening (recent contact vs. migration) were similar to the primary univariable analyses.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that higher quantitative results for the QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST were strongly associated with higher TB incidence rates, supporting existing data derived among adult and pediatric populations, from low and high TB incidence settings, respectively (9–11). This is the first study, however, to comprehensively assess the potential impact of implementing higher diagnostic thresholds for all three tests, using a uniquely powerful and well-characterized cohort. We found that implementing higher thresholds would lead to a marked loss of sensitivity for all three tests, whereby the majority of incident TB cases would test negative. A modest loss of test sensitivity may be acceptable in some circumstances, where the programmatic goal is to identify the subgroup with the highest risk of progression, if it is accompanied by a substantial improvement in PPV. However, PPV for all three tests remained ≤5%, even in the highest strata. Although this is likely partly a reflection of the low pretest probability of incident TB in low TB incidence settings (such as the United Kingdom), even among risk groups such as TB contacts and recent migrants, it also highlights the limitations of our existing diagnostic tests for predicting incident TB. Our previous analysis showed that TST stratified by BCG status yielded comparable performance to both commercial IGRAs (6). Our ROC curve data in the current analysis reinforces this conclusion, as AUROCs were very similar for all three tests, with overlapping 95% CIs.

These data demonstrate that implementing higher diagnostic thresholds for QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST is unlikely to be of use in settings aiming toward TB elimination and fails to bridge the gap to the WHO TPP for biomarkers with greater predictive value for incident TB. One approach may be to offer preventative therapy to all patients with positive LTBI tests, using current thresholds, with the offer of additional support to complete treatment to those with higher quantitative results, who are at highest risk of disease. However, such an approach should ensure that current resources are not diverted away from supporting those with lower quantitative positive test results to commence and complete preventative therapy because doing so would risk missing the majority of progressors.

Although our findings support the hypothesis that quantitative measures of T-cell recall (as measured by IGRAs and the TST) are correlates of risk of disease, which may reflect underlying mycobacterial burden, test sensitivity for incident TB cases was only 61.0–69.7% when using conventional thresholds over 3 years’ follow-up. This finding is consistent with recent data demonstrating IGRA sensitivity of 67–81%, even among prevalent TB cases (19). A negative IGRA in these examples may be a consequence of susceptibility to TB disease among a subgroup of exposed individuals who either fail to mount any adaptive immune response to M. tuberculosis, develop an immune response that is independent of IFN-γ (20), or have a localized response in tissue compartments that is not reflected in blood. Furthermore, in contrast to the hypothesis that a positive IGRA or TST are correlates of risk, cases of Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease show that T-helper cell type 1 responses that underpin IGRAs and the TST are necessary for protection against TB (21). This contradiction reflects the fact that IFN-γ–polarized T-cell responses do not discriminate between immunological protection and immunopathogenesis. Thus, these measures should be considered as imperfect correlates of risk when used for TB diagnosis, prognostication, or as outcome measures in vaccine efficacy studies (22).

This study reinforces an ongoing need for novel biomarkers that predict progression to incident TB more accurately, to facilitate precision delivery of therapy for LTBI to those who need it most, and thereby reduce the number needed to treat. Although IGRAs and the TST aim to detect immune sensitization to TB, it is increasingly recognized that tests that better delineate the spectrum of LTBI will be required to improve predictive value (23). One such example is whole-blood host transcriptional signatures, which have demonstrated promise for the detection of incipient, or subclinical, TB (24–27). However, a validated biomarker that achieves the WHO TPP for the prediction of incident TB has not yet been identified. In the interim, ensuring optimal implementation of existing LTBI tests is of paramount importance. Although higher diagnostic thresholds for QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST may not address this in isolation, inclusion of these quantitative results in a multivariable clinical risk model may improve prediction of incident TB, although existing tools remain unvalidated (4, 28).

This study has a number of strengths. First, it is a very large scale (n = 9,610), prospective study with lengthy median follow-up of almost 5 years, and robust identification of incident TB cases, including by linkage to national TB surveillance records. The study population, consisting of UK recent TB contacts and migrants from high–TB-incidence settings, is well characterized and highly representative of target groups for LTBI-screening programs in low–TB-incidence settings (3). Our findings are therefore likely to be generalizable to other low–TB-incidence countries. Furthermore, availability of diagnostic test results was very high, with QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST results available for 8,562 (89.1%), 8,079 (84.1%), and 7,833 (81.5%) of participants, respectively. The inclusion of a large number of both TB contacts and recent migrants also facilitated robust sensitivity analyses restricted to each subpopulation.

A limitation was that an updated version of the QFT-GIT (Qiagen), which became available late in the follow-up period, was not assessed in this study (29). Prospective evaluations of the predictive value of this assay for incident TB are required. Second, a positive LTBI test, done as part of the study, could potentially have led to differential reporting bias, as a positive result may have increased clinical suspicion of TB and therefore led to more TB diagnoses among participants with a positive test. However, test results were available to participants’ clinicians only for TB contacts aged ≤35 years because, during the study period, these were the only participants who met National Institute for Health and Care Excellence criteria for LTBI testing (15). The magnitude of this bias is therefore likely to be small. Third, only baseline testing was performed. We are therefore unable to assess conversions or reversions during serial testing, which may be frequent (30). Because the reality of both contact and migrant LTBI-screening programs is that serial testing (beyond 6 wk after contact) is highly unlikely to be cost-effective, this limitation reflects the constraints of routine programmatic conditions; the ability of the tests to identify progressors at the point of initial screening is therefore a key attribute. Finally, we are also unable to account for any further TB exposure events between recruitment and diagnosis, which may have led us to underestimate test sensitivity. However, 66.4% of progression events occurred in the first year (median time to disease, 188 d), and there is a generally low risk of TB transmission in the United Kingdom. Moreover, test sensitivity when using conventional thresholds remained 57.8–79.6% when follow-up was limited to 6 months; the impact of this bias is therefore likely small.

In conclusion, optimal implementation of existing LTBI diagnostic tests is critical while we continue to develop novel commercial assays with improved predictive value. Although higher quantitative QFT-GIT, T-SPOT.TB, and TST results were associated with higher TB incidence rates in this study, the implementation of higher diagnostic thresholds for these tests comes at the cost of a marked loss of sensitivity, such that only a minority of incident TB cases are detected. Moreover, the improvement in PPV with higher test thresholds was modest. Incorporation of quantitative results into validated multivariable risk prediction models may be of use to further improve prediction of incident TB in the short-to-medium term. However, a better biomarker is ultimately required to transform risk stratification of patients with LTBI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the entire UK PREDICT TB study team along with the study administrators, laboratory staff who did the tests, clinical and nursing colleagues who contributed to participant recruitment, and the data monitoring and study steering committees. The authors also thank all the temples, mosques, offices, and other community settings for their assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Program 08-68-01. In addition, R.K.G. was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (DRF-2018-11-ST2-004). I.A. was funded by NIHR (SRF-2011-04-001; NF-SI-0616-10037), Medical Research Council, UK Department of Health, and the Wellcome Trust. A.L. was funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Clinical Science, an NIHR Senior Investigator Award, and the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Respiratory Infection. F.D. was supported by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. M.N. is supported by the Wellcome Trust (207511/Z/17/Z) and by NIHR Biomedical Research Funding to University College London and University College London Hospitals.

Author Contributions: R.K.G. performed the analyses presented and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. F.D., J.J.D., A.L., and I.A. designed the UK PREDICT TB study. J.S. and I.A. led recruitment and follow-up of participants with all site principal investigators. C.J. and A.J.S. did the initial data cleaning and analysis with oversight from J.J.D. and I.A. Laboratory analyses were done by F.D., C.-Y.T., and A.L. J.D. and C.C. coordinated the updated linkage of cohort participants to national surveillance records. O.S. advised on predictive modeling strategies. All other authors contributed to the data collection, analysis methods, or interpretation. All authors have seen and agreed on the final submitted version of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201905-0969OC on December 11, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, Raviglione M. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2127–2135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1405427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015 [accessed 2017 Oct 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/strategy/End_TB_Strategy.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.World Health Organization. Latent TB infection : updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018 [accessed 2018 Aug 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2018/latent-tuberculosis-infection/en/ [PubMed]

- 4.Pai M, Denkinger CM, Kik SV, Rangaka MX, Zwerling A, Oxlade O, et al. Gamma interferon release assays for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:3–20. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00034-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR, Ling D, Menzies D, Mwansa-Kambafwile J, et al. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:45–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70210-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abubakar I, Drobniewski F, Southern J, Sitch AJ, Jackson C, Lipman M, et al. Prognostic value of interferon-γ release assays and tuberculin skin test in predicting the development of active tuberculosis (UK PREDICT TB): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1077–1087. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30355-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J, Berry NS, Taylor D, Venners SA, Cook VJ, Mayhew M. Knowledge and perceptions of latent tuberculosis infection among Chinese immigrants in a Canadian Urban Centre. Int J Family Med. 2015;2015:546042. doi: 10.1155/2015/546042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Development of a Target Product Profile (TPP) and a framework for evaluation for a test for predicting progression from tuberculosis infection to active disease 2017 WHO collaborating centre for the evaluation of new diagnostic technologies. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017 [accessed 2018 Aug 17]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259176/WHO-HTM-TB-2017.18-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 9.Andrews JR, Nemes E, Tameris M, Landry BS, Mahomed H, McClain JB, et al. Serial QuantiFERON testing and tuberculosis disease risk among young children: an observational cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:282–290. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winje BA, White R, Syre H, Skutlaberg DH, Oftung F, Mengshoel AT, et al. Stratification by interferon-γ release assay level predicts risk of incident TB. Thorax. 2018;73:652–661. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zellweger J-PP, Sotgiu G, Block M, Dore S, Altet N, Blunschi R, et al. Risk assessment of tuberculosis in contacts by IFN-γ release assays: a tuberculosis network European trials group study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1176–1184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0232OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Niemann S, Meywald-Walter K, Nienhaus A. Negative and positive predictive value of a whole-blood interferon-γ release assay for developing active tuberculosis: an update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:88–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0974OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geis S, Bettge-Weller G, Goetsch U, Bellinger O, Ballmann G, Hauri AM. How can we achieve better prevention of progression to tuberculosis among contacts? Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1743–1746. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00187112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta RK, Lipman M, Jackson C, Sitch A, Southern J, Drobniewski F, et al. Do higher quantitative interferon gamma release assay or tuberculin skin test results help to predict incident tuberculosis? Data from the UK PREDICT study. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:OA3822. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Tuberculosis clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011 [accessed 2015 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg117/resources/guidance-tuberculosis-pdf. [PubMed]

- 16.Leung CC, Yew WW, Au KF, Tam CM, Chang KC, Mak KY, et al. A strong tuberculin reaction in primary school children predicts tuberculosis in adolescence. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:150–153. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318236ae2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran-Mendoza O, FitzGerald JM, Marion S, Elwood K, Patrick D. Tuberculin skin test size and risk of TB among non-treated contacts of TB cases. Can Respir J. 2010;17:5B. [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitworth HS, Badhan A, Boakye AA, Takwoingi Y, Rees-Roberts M, Partlett C, et al. Interferon-γ Release Assays for Diagnostic Evaluation of Active Tuberculosis study group. Clinical utility of existing and second-generation interferon-γ release assays for diagnostic evaluation of tuberculosis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:193–202. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu LL, Smith MT, Yu KKQ, Luedemann C, Suscovich TJ, Grace PS, et al. IFN-γ-independent immune markers of Mycobacterium tuberculosis exposure. Nat Med. 2019;25:977–987. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bustamante J, Boisson-Dupuis S, Abel L, Casanova J-L. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: genetic, immunological, and clinical features of inborn errors of IFN-γ immunity. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:454–470. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemes E, Geldenhuys H, Rozot V, Rutkowski KT, Ratangee F, Bilek N, et al. C-040-404 Study Team. Prevention of M. tuberculosis infection with H4:IC31 vaccine or BCG revaccination. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:138–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esmail H, Barry CE, III, Young DB, Wilkinson RJ. The ongoing challenge of latent tuberculosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369:20130437. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zak DE, Penn-Nicholson A, Scriba TJ, Thompson E, Suliman S, Amon LM, et al. ACS and GC6-74 cohort study groups. A blood RNA signature for tuberculosis disease risk: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2016;387:2312–2322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suliman S, Thompson E, Sutherland J, Weiner Rd J, Ota MOC, Shankar S, et al. GC6-74 and ACS cohort study groups. Four-gene pan-African blood signature predicts progression to tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:1198–1208. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2340OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roe J, Venturini C, Gupta RK, Gurry C, Chain BM, Sun Y, et al. Blood transcriptomic stratification of short-term risk in contacts of tuberculosis Clin Infect Dis 202070731–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta RK, Turner CT, Venturini C, Esmail H, Rangaka MX, Copas A, et al. Concise whole blood transcriptional signatures for incipient tuberculosis: a systematic review and patient-level pooled meta-analysis Lancet Respir Med [online ahead of print] 17 Jan 2020; DOI: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30282-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menzies D, Gardiner G, Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M. Thinking in three dimensions: a web-based algorithm to aid the interpretation of tuberculin skin test results. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barcellini L, Borroni E, Brown J, Brunetti E, Codecasa L, Cugnata F, et al. First independent evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB Plus performance. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1587–1590. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02033-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tagmouti S, Slater M, Benedetti A, Kik SV, Banaei N, Cattamanchi A, et al. Reproducibility of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) release assays: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1267–1276. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201405-188OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.