Emerging infectious diseases are those that have appeared for the first time in a population, increased rapidly in incidence or range or developed antimicrobial resistance. 1 Emerging infectious disease outbreaks have increased since 1940, 2 , 3 due in part to changes in the human–animal–environment interface and, between 1940 and 2004, 60% of such outbreaks were caused by zoonotic pathogens. 2 , 4 Emerging infectious diseases have caused the highest mortality impact human pandemics in history, including plague, pandemic influenza in 1918/1919 and HIV. 5 Furthermore, antimicrobial resistance is increasing internationally and has been described by World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Margaret Chan as a “slow‐motion tsunami”. 6

There are often parallels between resistant infections in humans and animals, demonstrating the important links between human and animal health; for example, the discovery of colistin‐resistant Escherichia coli in China, 7 and fluoroquinolone‐resistant Campylobacter jejuni in New Zealand 8 in humans and animals. There is a strong association between antimicrobial resistance and modern livestock rearing, with the overuse of antimicrobials in livestock an important factor in the development of resistance in some pathogens that infect humans, or in the emergence of new resistant organisms. 9 Expansion of urban environments has led to increased interaction between wildlife and livestock, and climate change is an important enabling factor for transmission of many infections; for example, affecting mosquito populations competent for arboviruses.

The world contains multiple pathogens with new pandemic potential. WHO now conducts an extensive annual consultation to identify high priority hazards. 10 Their current list includes nine pathogens (or groups of pathogens) with high potential to cause a public health emergency and where limited preventive and curative measures are available: 11

Arenaviral haemorrhagic fevers (including Lassa Fever)

Crimean Congo Haemorrhagic Fever

Filoviral diseases (including Ebola and Marburg)

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

Other highly pathogenic coronaviral diseases (such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome [SARS])

Nipah and related henipaviral diseases

Rift Valley Fever

Severe Fever with Thrombocytopaenia Syndrome

Zika

In addition to the above is the persisting threat from traditional pandemics (such as from new influenza viruses), and even the persisting risks from engineered bioweapons (some of which could reach New Zealand). 12

It is therefore important and timely to consider how New Zealand can prepare for the next emerging infectious disease pandemic, taking into account the vastly different ways in which it might present – from another SARS, to a zoonotic disease with current stuttering transmission to humans such as Nipah virus, or a common pathogen that has developed complete resistance to antibiotics. In this commentary, we consider possible responses, building on: i) a Public Health Summer School day and a follow‐up workshop that included a range of Australian and New Zealand experts in February 2017; ii) a New Zealand workshop in 2015 involving medical officers of health; and iii) some initial thinking by us in a blog post on this topic. 13

What are the possible responses?

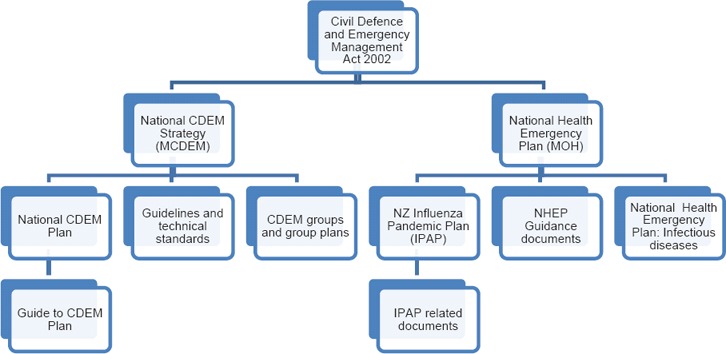

New Zealand's pandemic planning is currently embedded in the Civil Defence and Emergency Management framework (see Figure 1). This arrangement is recommended by WHO 14 , 15 and is the general pattern for developed countries. However, within these documents, very little guidance exists for infectious diseases with pandemic potential other than influenza. The National Health Emergency Plan: Infectious Diseases, developed in response to SARS in 2003 16 is now out‐of‐date, and the core New Zealand pandemic planning and response document is the Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Plan 2010. 17 The Ministry of Health's ‘Pandemic Planning and Response’ webpage links only to documents regarding influenza. 18 However, preparedness for pandemic influenza does not guarantee preparedness for another emerging infectious disease, as demonstrated by the emergence of blood‐borne (Ebola) and vector‐borne (Zika) threats in recent years.

Figure 1.

New Zealand's currents strategic pandemic response framework for emergencies, including epidemic/pandemic emergencies.

The International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005 are a binding agreement between 196 countries aiming to prevent and respond to the international spread of disease. 19 (a2) They require States to assess, strengthen and maintain core capacities for surveillance, risk assessment, reporting and response, and notify WHO of all events that may represent a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, including unnamed diseases or events, aiming for an all‐hazards approach. 19 Antimicrobial resistance is not specifically listed in the IHR, but is included in the guide to implementation as a risk to be targeted by national initiatives. 20 Although the IHR have been widely criticised, it was a lack of implementation rather than the agreement itself that was responsible for failures in this response, according to the Review Committee on the role of the IHR (2005) in the Ebola outbreak and response. 21 Unfortunately there has been only a partial international response to the IHR, with just 35% of State Parties (including New Zealand) having core capacities in place by the end of 2015. 21 , 22 Full implementation will require support for low‐income countries to strengthen their health systems. 21

The Review Committee has developed a draft implementation plan for their recommendations. This aims to: accelerate countries’ implementation of IHR, with particular focus on countries with high vulnerability to emerging infectious diseases and low capacity; strengthen WHO's capacity to implement IHR and respond to emergencies; and improve monitoring of IHR core capacities by introducing a joint external evaluation tool. 23 One facet of this implementation plan is the development of a five‐year global strategic plan by WHO and will emphasise the importance of making use of existing frameworks, including the Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases (APSED). 23

Other frameworks have been developed to assist countries to implement the IHR, notably the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA). This was launched in 2014 by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with 43 other countries, WHO, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, the World Organization for Animal Health, and civil society. 24 , 25 It aims to promote global health security and accelerate progress towards full IHR implementation. 25 Eleven ‘Action Packages’ (Table 1) encompass the three key elements of health security: prevention, detection, and response, 26 each with five‐year targets, actions and indicators. These action packages are intended to facilitate specific commitments and leadership from countries involved. An assessment tool for essential national structures and functions has also been developed and piloted. 25

Table 1.

Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) Action Packages.

| Key domain | More specific areas |

|---|---|

|

Prevent |

1. Antimicrobial resistance 2. Zoonotic disease 3. Biosafety and biosecurity 4. Immunisation |

|

Detect |

5. Laboratory system 6. Real‐time surveillance 7. Reporting 8. Workforce development |

|

Respond |

9. Emergency Operations Centres 10. Linking public health with law and multi‐sectoral rapid response 11. Medical countermeasures and personnel deployment |

The recently developed IHR (2005) core capacities joint external evaluation tool is structured similarly, with 19 areas grouped under the headings ‘prevent’, ‘detect’, ‘respond’ and other IHR‐related hazards and points of entry. 23 It is recommended that countries undertake one external evaluation every four years. 23

APSED is a strategic framework for countries of the Western Pacific and South East Asian regions to strengthen their capacity to manage and respond to emerging infectious disease threats, and comply with IHR (2005). 27 It recommends collaboration mechanisms between human and animal health sectors, and that national pandemic preparedness and response plans should be integrated into a public health emergency plan for all emerging infectious diseases. 28 Its third version is currently in draft and now has eight focus areas: public health emergency preparedness; surveillance risk assessment and response; laboratories; zoonoses; prevention through health care (including antimicrobial resistance); risk communication; regional preparedness alert and response; and monitoring and evaluation. 9 At a recent (February 2017) meeting hosted by the Health Environment and Infection Research Unit of the University of Otago and the Integrated Systems for Epidemic Response, public health professionals saw APSED as the appropriate mechanism with which to develop IHR core capacities across the South Pacific.

The IHR specifies a number of diseases that constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, but neither APSED or GHSA provide guidance on development of preparedness for particular diseases or categories. A number of frameworks have been created to methodically prioritise or classify diseases to inform such development; for example, through expert consensus on diseases of national or international importance using number of pre‐set criteria. 29 , 30 , 31 Some studies have focused on zoonoses, and others have focused on specific aspects of disease prioritisation or a specialised group of diseases; for example, prioritising solely for surveillance or assessing emerging diseases only.

The national public health institute of Germany, the Robert Koch Institute, has selected 127 pathogens notifiable by German law, reportable within the European Union or to WHO, with potential for deliberate release or with dedicated chapters in a manual of infectious diseases. 32 It then used previous research and expert scoring to determine pathogen importance as a risk to population health. 32 Some pathogens that scored highly had already been identified as priorities, such as HIV and influenza, but the potential importance of others (such as Hantavirus) was newly recognised through this process. 32 Similarly, the National Expert Panel on New and Emerging Infections of the United Kingdom (UK) developed a two‐algorithm risk assessment process for emerging infectious diseases, considering the likelihood a pathogen will infect the population and its potential impact on human health. 33 This tool has been used to assess the threat of a range of infections in the UK and communicate information to government departments and other agencies. 33

Many authors state that one of the most effective ways to test and improve pandemic preparedness is by conducting exercises. 34 Reports from exercises undertaken around the world detail their benefits. They give stakeholders the opportunity to deepen their understanding of crisis issues, clarify policies and processes, and build up trust and familiarity that can lead to faster decision making during a crisis. 35 , 36 New Zealand public health professionals also emphasise the importance of exercises in building capacity, 37 and simulation exercises will form part of the new IHR core capacity monitoring and evaluation framework. 23

What more can and should New Zealand do to prepare?

A New Zealand‐based workshop and series of interviews with public health professionals (undertaken by one of us in 2015), 37 assessed utility of ranking pandemic ‘scenarios’ to inform planning. These were thought to be a useful way to consider threats for training and testing capacity. Other key components of emerging infectious disease preparedness identified during these discussions were retention of institutional knowledge, exercising responses, national public health leadership and consideration of potential impact on vulnerable populations. Surveillance outside notifiable diseases and laboratory capacity for highly pathogenic organisms were identified as major gaps in current New Zealand preparedness. Recommendations from New Zealand health sector debriefs on the response to Ebola also emphasised the need for further development of intelligence, communication and decision support tools and a framework providing for infectious disease management across a range of disease types and transmission methods. 38

The recent workshop convened by the Health Environment and Infection Research Unit of the University of Otago and the Integrated Systems for Epidemic Response aimed to identify opportunities to strengthen capacity to prevent and respond to emerging infectious diseases, particularly in the South Pacific. Participants discussed the need for technical and financial support from Australia and NZ for Pacific Island countries in epidemiology, laboratory capacity and infection prevention and control, and recommended that countries in the region are encouraged to assess their capacity for responding to public health emergencies using appropriate tools such as the joint external evaluation tool. The need for field epidemiology training in public health workforce development was emphasised, and steps towards ensuring public health data is rapidly available and better utilised were discussed, including undertaking a stocktake of returned traveller surveillance and use of rapid electronic journals (e.g. Eurosurveillance). It was recommended that a health or development agency perform a regional surveillance needs assessment to guide development of an operational plan under APSED, and that agencies in the region continue to strengthen collaboration between human and animal health sectors at all levels with a view to developing an effective One Health platform.

Given this background, (particularly the IHR Core Components Questionnaire, the APSED Framework, and the GHSA Action Packages), we recommend New Zealand health authorities should consider the following priorities:

Prevention

Completing and implementing an antimicrobial resistance action plan (currently in development). 39 In particular, there is a need to strengthen collaboration between human and animal health sectors in this domain.

Detection

Developing laboratory capacity for highly pathogenic organisms (ideally with shared planning and capacity building with Australia to maximise cost‐effectiveness).

Developing real time surveillance beyond notifiable diseases and influenza. (We note past New Zealand work on developing a framework for surveillance that could be used.) 40

Response

Developing or adopting a framework to cover prevention, detection and response to a broad range of emerging infectious diseases, especially those with greatest potential to spread in our region. Scenarios or disease prioritisation could be used to facilitate this process. Doing this would be in line with IHR core capacity development and New Zealand's own Ebola debrief recommendations and could be undertaken as part of the next review of the National Health Emergency Plan: Infectious Diseases.

Conducting regular exercises to test plans for emerging infectious diseases other than pandemic influenza (but additional exercises on pandemic influenza are still warranted, e.g. every 5–10 years).

Undertaking regular joint external assessments of IHR core capacities both in New Zealand, and assisting low‐ and middle‐income countries in the Pacific Region to undergo assessments and develop their capacities.

Many of these suggested priorities could be performed with minimal cost. However, we acknowledge that where costs are substantive then further evaluation of the costs and benefits should be performed. For example, for some types of laboratory capacity it might be optimal if New Zealand contributes resources to a single Australian‐based service.

In summary, there is a continual need in an increasingly globalised world for all nations to continuously review and upgrade their responses to emerging infectious disease threats. For New Zealand, there are a range of potential options for further strengthening capacity to prevent, detect and respond to such threats.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of: i) the Medical Officers of Health who participated in a 2015 workshop; ii) the contributors to the Public Health Summer School on Emerging Infectious Diseases in February 2017; and iii) the workshop participants from official agencies and Australia (also in February 2017).

References

- 1. McCloskey B, Dar O, Zumla A, Heymann DL. Emerging infectious diseases and pandemic potential: status quo and reducing risk of global spread. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1001–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ross AG, Crowe SM, Tyndall MW. Planning for the next global pandemic. Int J Infect Dis 2015;38:89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gautret P, Gray GC, Charrel RN, Odezulu NG, Al‐Tawfiq JA, Zumla A, et al. Emerging viral respiratory tract infections—environmental risk factors and transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging infectious diseases: Threats to human health and global stability. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan M. WHO Director‐General Briefs UN on Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. Geneva (CHE): World Health Organization Director General's Office; 2016. [cited 2017 Jan 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2016/antimicrobial-resistance-un/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu Y‐Y, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi L‐X, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid‐mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR‐1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williamson D, Baker M, French N, Thomas M. Missing in action: An antimicrobial resistance strategy for New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2015;128:65–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization Regional Committee for the Western Pacific . DRAFT Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases and Public Health Emergencies: Advancing Implementation of the International Health Regulations Beyond 2016 [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WPRO; 2016. [cited 2017 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/about/regional_committee/67/documents/wpr_rc67_9_apsed.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kieny M‐P. Emergency Preparedness, Response: R&D Blueprint for Action to Prevent Epidemics [Internet]. Geneva (CHE): World Health Organization; 2017. [cited 2017 Feb 13]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/research-and-development/blueprint/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization . Revised List of Priority Diseases, January 2017 [Internet]. Geneva (CHE): World Health Organization; 2017. [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/research-and-development/list_of_pathogens/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson N, Lush D. Bioterrorism in the Northern Hemisphere and potential impact on New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2002;115:247–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scott J, Wilson N, Baker M. Improving New Zealand's preparations for the next pandemic. 2017 Feb 1 In: Public Health Expert Blog [Internet]. Otago: University ofOtago; [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2017/02/01/improving-new-zealands-preparations-for-the-next-pandemic/ [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . Consultation on the Health Emergency Risk Management Framework and Improving Public Health Preparedness: Meeting Report. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . Pandemic Influenza Risk Management: WHO Interim Guidance. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ministry of Health New Zealand . National Health Emergency Plan: Infectious Diseases. Wellington (NZ): Government of New Zealand; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ministry of Health New Zealand . New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan: A Framework for Action. Wellington (NZ): Government of New Zealand; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ministry of Health New Zealand . Pandemic Planning and Response. Secondary Pandemic Planning and Response [Internet]. Wellington (NZ): Government of New Zealand; 2015. [cited 2016 Jul 7]. Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/emergency-management/pandemic-planning-and-response [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization . International Health Regulations. 2nd ed. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization . International Health Regulations (2005) Areas of Work for Implementation [Internet]. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2007. [cited 2017 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/ihr/IHR_Areas_of_work.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization . Implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005): Report of the Review Committee on the Role of the International Health Regulations (2005) in the Ebola Outbreak and Response [Internet]. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2016. [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_21-en.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization . International Health Regulations (2005) Summary of State Parties 2013 Report on IHR Core Capacity Implementation: Regional Profiles. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization . Draft Global Implementation Plan for the Recommendations of the Review Committee on the Role of the International Health Regulations (2005) in the Ebola Outbreak and Response [Internet]. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2016. [cited 2017 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/about-us/governance/regional-committee-for-europe/66th-session/documentation/working-documents/eurrc6626-draft-global-implementation-plan-for-the-recommendations-of-the-review-committee-on-the-role-of-the-international-health-regulations-2005-in-the-ebola-outbreak-and-response [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frieden TR, Tappero JW, Dowell SF, Hien NT, Guillaume FD, Aceng JR. Safer countries through global health security. Lancet. 2014;383:764–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Global Health Security Agenda [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2014. [cited 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/security/ [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Global Health Security Agenda: Action Packages [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2014. [cited 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/security/actionpackages/default.htm [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization . Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases Progress Report 2014: Securing Regional Health. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization . Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases 2010. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ng V, Sargeant JM. A quantitative and novel approach to the prioritization of zoonotic diseases in North America: A public perspective. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Balabanova Y, Gilsdorf A, Buda S, Burger R, Eckmanns T, Gärtner B, et al. Communicable diseases prioritized for surveillance and epidemiological research: Results of a standardized prioritization procedure in Germany, 2011. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ng V, Sargeant JM. A stakeholder‐informed approach to the identification of criteria for the prioritization of zoonoses in Canada. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balabanova Y, Gilsdorf A, Buda S, Burger R, Eckmanns T, Gartner B, et al. Communicable diseases prioritized for surveillance and epidemiological research: Results of a standardized prioritization procedure in Germany, 2011. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morgan D, Kirkbride H, Hewitt K, Said B, Walsh AL. Assessing the risk from emerging infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:1521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horvath J. Commonwealth pandemic preparedness plans. N S W Public Health Bull. 2006;17:112–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tay J, Ng YF, Cutter J, James L. Influenza A (H1n1‐2009) pandemic in singapore–public health control measures implemented and lessons learnt. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:313–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Health Protection Agency . Exercise Winter Willow Lessons Identified. Edinburgh (UK): Government of Scotland; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scott J. Developing New Zealand's Pandemic Preparedness. Wellington (NZ): University of Otago; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ministry of Health New Zealand . Response to Suspected Ebola Virus Disease Cases in New Zealand: Key Themes from Sector and Ministry Debriefs [Internet]. Wellington (NZ): Government of New Zeland; 2015. [cited 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/ebola-updates/ebola-information-health-professionals [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ministry of Health New Zealand . Antimicrobial Resistance Strategic Action Plan Development Group [Internet]. Wellington (NZ): Government of New Zeland; 2016. 2016 [cited 2016 Feb 18]. Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/antimicrobial-resistance/antimicrobial-resistance-strategic-action-plan-development-group [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baker MG, Easther S, Wilson N. A surveillance sector review applied to infectious diseases at a country level. BMC Public Health 2010;10:332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]