Abstract

We sought to develop a quality standard for the delivery of psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that is both consistent with the underlying evidence supporting psychotherapy as a treatment for PTSD and associated with the best levels of symptom improvement. We quantified psychotherapy receipt during the initial year of PTSD treatment in a 10-year national cohort of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) users who completed patient-reported outcome measurement as part of routine practice. We added progressively stringent measurement requirements. The most stringent requirement was associated with superior outcomes. Quality of psychotherapy for PTSD in the VA improved over time.

Keywords: Quality of Healthcare, Patient Reported Outcomes Measures, Comparative Effectiveness Research, Psychotherapy, Stress Disorders, Posttraumatic

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that may follow exposure to a traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Symptoms include reexperiencing the trauma, avoidance of reminders of the trauma, arousal, and negative cognitions. PTSD affects approximately 6% of the United States (US) population during their lifetime (Goldstein et al., 2016; Pietrzak, Goldstein, Southwick, & Grant, 2011). Rates are higher in combat or military-exposed populations such as veterans who use health services provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA; Holowka et al., 2014; Shiner, Drake, Watts, Desai, & Schnurr, 2012). The VA has implemented multiple effective treatments for PTSD, including two specific evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) protocols (Karlin & Cross, 2014): Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) and Prolonged Exposure (PE). CPT is comprised of twelve weekly 60-minute sessions of cognitive therapy, during which veterans address maladaptive thoughts associated with their worst traumatic event (Patricia A. Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2017). CPT can be administered either in an individual therapy format or a group format (P. A. Resick et al., 2015). PE consists of nine to twelve weekly 90-minute sessions of trauma-associated imaginal and in-vivo exposures administered in an individual therapy format (Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007). Research trials of CPT and PE have resulted in statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in veterans’ PTSD symptoms (Haagen, Smid, Knipscheer, & Kleber, 2015). The VHA Uniform Mental Health Services Package mandated the availability of these treatments in VHA clinics beginning in 2008 (Kussman, 2008).

Measuring the implementation of EBPs for PTSD has been a challenge. Single-site studies have used labor-intensive chart review to identify psychotherapy notes indicating the provision of EBPs (Hundt et al., 2015; Kehle-Forbes, Meis, Spoont, & Polusny, 2016; Lamp, Maieritch, Winer, Hessinger, & Klenk, 2014; Lu, Plagge, Marsiglio, & Dobscha, 2016; Mott, Mondragon, et al., 2014; Mott, Stanley, Street, Grady, & Teng, 2014; Shiner, Bateman, et al., 2012). Studies attempting to measure implementation of EBPs for PTSD nationally have relied on use of psychotherapy procedural codes (Cully et al., 2008; Mott, Hundt, Sansgiry, Mignogna, & Cully, 2014), with some assumptions about how the number and timing of encounters indicate that an EBP could have been delivered (Seal et al., 2010; Spoont, Murdoch, Hodges, & Nugent, 2010). For example, Spoont et al. (2010) measured whether patients had at least eight encounters associated with a psychotherapy procedural code over the course of 6 months (Spoont et al., 2010), while Seal et al. (2010) determined whether those encounters occurred over the course of 15 weeks (Seal et al., 2010). However, assumptions about the use of psychotherapy procedural codes may be incorrect, as these codes are not protocol-specific.

We have performed three studies using automated natural language processing (NLP) of psychotherapy notes to bridge the gap between laborious chart review and efficient but potentially inaccurate use of psychotherapy procedural codes. NLP is a method to abstract information from large unstructured bodies of note text (Meystre, Savova, Kipper-Schuler, & Hurdle, 2008). Our general approach has been to use machine learning to train a computer to mimic the judgments of expert clinicians in classifying clinical notes (Hripcsak & Wilcox, 2002); in our case, practicing therapists classify whether a psychotherapy note describes the provision of an EBP for PTSD. In our initial (single-site) study, we found that in 43% of encounters with psychotherapy procedural codes, the associated notes described services other than psychotherapy, such as intakes, psychological testing, and case management services (Shiner, D’Avolio, et al., 2012). This raised concerns about the accuracy of psychotherapy procedural codes. In our second (regional) study of 1,924 patients enrolling in six specialized outpatient PTSD clinics, patients had a mean of 9.1 encounters with psychotherapy procedural codes over their initial six months of treatment, but only 0.4 of these were EBP sessions (Shiner et al., 2013). Importantly, 6.1% (n=121) patients received at least one EBP session. This showed both that having a given number of encounters was not a proxy for receiving EBP and that it is possible to measure EBP delivery with an automated NLP-based classifier. In our third (national) study of 255,933 Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, we found that 20.2% (n=51,852) received at least one EBP session over a median of 4.1 years of observation (Maguen et al., 2018). This showed we could efficiently apply an automated NLP-based classifier to a large national population. However, in focusing on Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, this study examined only a subset of VA patients with PTSD. Additionally, this work did not examine the adequacy of treatment for patients who received EBP.

Donabedian (1997) proposed a framework for measuring healthcare quality that divides measures into domains of structure, process, and outcome (Donabedian, 1997). In Donabedian’s model, a quality measure assessing whether patients with PTSD received an EBP would fall under the process domain. Such process measures would allow healthcare teams to assess the effectiveness of their efforts to improve the quality of care that they deliver. For example, staff members at a VA mental health clinic trying to increase the number of patients who receive EBP for PTSD might use such a process measure to understand whether their improvement intervention has worked. However, this model is predicated upon the validity of the quality measure. Chassin, Loeb, Schmaltz, and Wachter (2010) proposed that to be valid, a quality measure must capture whether an evidence-based care process has actually been provided. In the case of EBP for PTSD, the receipt of at least one session is an insufficient measure of quality because the studies establishing the efficacy of EBP for PTSD typically require multiple weekly sessions delivered by the same therapist over several months. Therefore, now that we can classify whether encounters associated with psychotherapy procedural codes include the provision of EBP, the next step is to examine the effect of increased measurement requirements designed to better approximate the evidence-based care process.

This study expands our work to all veterans who initiated PTSD care in VA from 2004 through 2013. This was a time of intense demographic change (Hermes, Rosenheck, Desai, & Fontana, 2012; Rosenheck & Fontana, 2007) and resource reallocation (Wagner, Sinnott, & Siroka, 2011) in VA, with a national focus on improving the capacity of the VA mental health treatment system to deliver evidence-based treatments (Karlin & Cross, 2014; Rosen et al., 2016). Our objectives were to: (1) measure the delivery of EBPs for PTSD to a national cohort of Veterans from diverse service eras; (2) determine longitudinal trends in EBP for PTSD delivery according to potential quality measures; and (3) determine whether quality measures that more stringently reflect the evidence supporting EBPs are associated with superior outcomes. While the VA has operationalized an EBP reporting strategy that leverages therapist-completed medical record templates (Sripada, Bohnert, Ganoczy, & Pfeiffer, 2018), our prior work has shown that uptake of the templates has lagged therapist-reported use of EBPs (Shiner, Leonard Westgate, et al., 2018). As efforts to incentivize the use standardized reporting tools such as templates are implemented (Sripada, Pfeiffer, Rauch, Ganoczy, & Bohnert, 2018), we feel that our work leveraging historical data will be informative to the VA and other large healthcare systems as they look to leverage these diverse data sources to develop valid quality measures to help drive improvement (Brown, Scholle, & Azur, 2014; Hepner et al., 2016).

Method

Data Source

We used the VA corporate data warehouse (CDW) to identify patients with new PTSD treatment episodes from fiscal year 2004 (FY04) through FY13. We obtained patient demographic information as well as encounter, diagnostic, patient-reported outcome, and pharmacy data from the CDW. The Veterans Institutional Review Board of Northern New England and VA National Data Systems approved this study.

Patients

We included VA users who received a primary diagnosis of PTSD at two or more outpatient encounters, at least one of which occurred in a mental health setting, over the course of 90 days between October 1, 2003 and September 30, 2013 and had not met this criterion during the prior two years. We examined one year of treatment receipt following the first diagnosis of the two qualifying diagnoses. This was called the “index PTSD diagnosis.” When patients met the cohort inclusion criteria multiple times over the 10-year period, only their first episode was included. This resulted in a cohort of 731,520 patients. This cohort has been previously described elsewhere (Shiner, Leonard Westgate, Bernardy, Schnurr, & Watts, 2017; Shiner, Leonard Westgate, Harik, Watts, & Schnurr, 2016; Shiner, Westgate, Bernardy, Schnurr, & Watts, 2017).

Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD Receipt

We identified all encounters associated with psychotherapy procedural codes for each patient during the one-year period of observation and linked these encounters to the related treatment notes. This resulted in a set of 18,185,216 documents. We used our previously-developed NLP-based classifier, which has an overall classification accuracy of 0.92 (Maguen et al., 2018), to determine whether each document described the provision of psychotherapy at all, whether psychotherapy documents described the provision of PE or CPT, and whether CPT was delivered in a group or an individual format (CPT-G, CPT-I). We found that 0.5% (n=88,674) of documents described PE, 0.8% (n=143,147) of documents described CPT-G, 1.2% (n=217,250) of documents described CPT-I, 30.6% (n=5,558,844) of documents described other group or individual psychotherapy, and 67.0% (n=12,177,301) of documents did not describe psychotherapy at all.

Measures of Psychotherapy Quality

We followed a series of progressively restrictive steps in calculating our putative measures of psychotherapy quality. First, we used the NLP-based classifier results to determine whether each patient received any psychotherapy, any individual psychotherapy, any group psychotherapy, as well as each of the EBPs during their initial year of treatment based on their clinical notes. Second, we added a requirement that patients had an “adequate” number of psychotherapy sessions, defined here as eight or more sessions. Outcomes research in psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders has indicated that half of patients achieve a clinically meaningful improvement after eight sessions (Howard, Kopta, Krause, & Orlinsky, 1986). Similarly, most patients who respond to evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD have achieved the bulk of their gains by session eight (Galovski, Blain, Mott, Elwood, & Houle, 2012; Tuerk et al., 2011). Third, we added a requirement that the eight sessions be delivered by the same therapist. Continuity of care is associated with improved health outcomes across disorders (van Walraven, Oake, Jennings, & Forster, 2010), and in mental health treatment in particular (Adair et al., 2005). For group therapy led by two-therapist teams, each therapist was considered separately for meeting this requirement. Fourth, we added a requirement that eight sessions be delivered during a 14-week period. Because both PE and CPT are designed for delivery in a weekly or twice-a-week format (Foa et al., 2005; P. A. Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002), this requirement ensures that the sessions are spaced in a similar manner to the efficacy trials supporting clinical practice, while allowing some flexibility for missed or rescheduled sessions. This treatment density standard has been used as part of VA psychotherapy performance measures (Trafton et al., 2013).

Concurrent Evidence-Based Medication for PTSD Receipt

We determined whether patients also received adequate trials of evidence-based medications for PTSD. To do this, we examined all medications dispensed by VA pharmacies during the year following the index PTSD diagnosis. Antidepressant drug names were classified into categories for individual agents and an overall category. The antidepressant drug class label was used to confirm our coding. We determined whether patients received one of the four effective antidepressants for PTSD specifically recommended in the VA/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline (VA/DoD CPG) in place during the time our cohort received treatment (Friedman, Lowry, & Ruzek, 2010). These included fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. For patients who received one of the four effective antidepressants for PTSD, we determined whether they received an adequate treatment, which we defined as eight weeks of a daily dose at least as high as the dose used in the efficacy trials supporting the treatment recommendation (Jonas et al., 2013; Watts et al., 2013). While the length of efficacy trials of psychotropic medications for PTSD varies, the VA/DoD CPG recommended medication trials of at least eight weeks (Friedman et al., 2010). Therefore, participants receiving continuous treatment of one of the following medications daily for eight weeks or more were considered to have received an adequate medication trial (AMT): fluoxetine 20 mg or more daily, paroxetine 20 mg or more daily, sertraline 100 mg or more daily, and venlafaxine 150 mg or more daily.

Covariates

We developed three groups of covariates. First, we examined patient characteristics, such as age, gender, race, military service era, rurality, military-related exposures (including combat and sexual trauma), and medical and psychiatric comorbidities. Second, we examined health service use characteristics including prior receipt of psychotherapy, outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and admissions. For prior receipt of psychotherapy, we assessed whether patients had an outpatient encounter associated with psychotherapy procedural codes in the two years prior to their index PTSD diagnosis. Outpatient visits included visits to specialized PTSD clinics, general mental health clinics, substance abuse clinics, and integrated primary care-mental health clinics. Emergency department visits included those for a psychiatric indication. Admissions included stays on an acute inpatient psychiatric clinic, a residential PTSD treatment program, or a residential substance abuse program. Third, we examined therapist characteristics. Patients were assigned a primary therapist based on the clinician who completed the plurality of their psychotherapy encounters. Primary therapists were characterized by age, gender, service section, and professional background. Service section included specialized PTSD, general mental health, substance abuse, and primary care-mental health integration clinics. Because individual therapists may work across multiple service sections, we calculated the percentage of time they spend seeing PTSD patients in various settings. This was based on our assumption that therapists who spend a higher percentage of their time in specialized PTSD settings may bring increased knowledge and experience in treating PTSD, even when seeing patients in non-specialized settings. Professional background included psychologist, social worker, nurse, and psychiatrist. To account for the possibility that some psychotherapy might be delivered briefly in the course of medication management, we assessed whether each provider had prescription privileges.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment

Use of patient-reported outcome measurement using the PTSD Checklist (PCL; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) as part of routine practice became more common beginning in FY08 (Shiner, Westgate, et al., 2018). Therefore, we obtained available PCL data for the FY08–13 portion of the cohort. During these years, the VA used the version of the PCL corresponding to PTSD diagnostic criteria in the fourth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Wilkins, Lang, & Norman, 2011). This version of the PCL was a 17-item measure with each item rated on a five-point Likert-type scale, resulting in total scores ranging from 17 through 85 (Weathers et al., 1993). Respondents were asked to rate how much they are bothered by each symptom over the last month. Symptom presence was determined by a response of “moderately” or greater (Weathers et al., 1993). Therefore, the tool could be used to determine whether patients meet minimal symptomatic criteria for PTSD according to DSM-IV, defined as one re-experiencing symptom, three avoidance and numbing symptoms, and two hyperarousal symptoms. Clinically meaningful improvement has been previously defined as a decrease of 10 points or more on the PCL (Monson et al., 2008). A clinically meaningful improvement in PTSD symptoms plus no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD has been shown to be an important marker of improved quality of life (Schnurr & Lunney, 2016).

Analysis

Our analysis plan was divided into descriptive and causal elements. For descriptive analyses using the entire FY04–13 cohort, we summarized cohort characteristics and compared patients who had at least one encounter that was administratively coded as psychotherapy with those who did not using t-test or χ2 analysis, as appropriate. We then described psychotherapy receipt as measured using both administrative coding and the NLP-based clinical note classification algorithm for the entire cohort during each fiscal year and for the overall 10-year period. We then focused on psychotherapy initiation by excluding patients who had encounters that were administratively coded as psychotherapy in the two years prior to their index PTSD diagnosis and recalculated initiation rates for each psychotherapy category for each individual fiscal year and for the overall 10-year period. We progressively added the measures of psychotherapy quality described above to this sub-cohort newly initiating psychotherapy, representing the cumulative number of patients who met each increasingly restrictive standard during their first year of PTSD treatment.

For causal analyses using patients from the FY08–13 portion of the cohort, we identified patients who initiated EBP at progressively higher levels of adherence to our “quality” measures (8 visits, 8 visits with the same therapist, 8 visits with the same therapist within 14 weeks) and had concurrent symptoms measurement using the PCL, as defined below. We created orthogonal comparison groups by including patients only in the longitudinally earliest (first during treatment year) quality standard that they met. Patients who initiated care that met multiple quality standards on the same day were assigned to the strictest standard met on that day. From this group, we selected patients who had a minimum of a PCL score at or before the second session (baseline) but no more than 14 days prior to the first session, and at or after the seventh session (follow-up) but no more than 14 days after the eighth session. To ensure patients had active PTSD symptoms at baseline, we required that they meet DSM-IV symptomatic criteria on their baseline PCL. When there were multiple PCL scores meeting our baseline criterion, we selected the measure closest to session 1. When there were multiple PCL scores meeting our follow-up criterion, we selected the measure closest to session 8. We calculated two change measures from baseline to follow-up: 1) mean PCL change, and 2) “loss of diagnosis,” which included both no longer meeting symptomatic criteria for PTSD plus experiencing a meaningful decrease in symptoms of 10 points or more.

Following a procedure developed in prior work (Shiner, Westgate, et al., 2018), we examined both the raw change in PTSD symptoms among those with measurement and the patient characteristic-weighted mean change, as well as the percentage of patients achieving our reliable change and loss of diagnosis criteria. Given that we were comparing three conditions (8 visits, 8 visits with the same therapist, 8 visits with the same therapist within 14 weeks), we used a conservative Bonferroni-corrected alpha of p<0.0167 for pre/post comparisons to avoid type I error. We balanced patient characteristics that have a plausible association with the outcome using inverse propensity of treatment weighting (IPTW; Stuart, 2010). We estimated propensity scores with multinomial logistic regression using generalized booster effects (McCaffrey et al., 2013), in which case the dependent variable is an indicator for the quality standard met and the independent variables are an antiparsimonious specification of variables that have a plausible correlation with the outcome. Using these propensity scores, we weighted participants in order to balance the pretreatment covariate distribution. Covariates in the IPTW model included baseline PCL score, number of days between the baseline PCL and session 1, number of days between follow-up PCL and session 8, and all covariates described in Table 1. In balancing almost 50 patient characteristics, a Bonferroni correction would indicate a corrected alpha of p<0.001. However, we conservatively maintained an alpha threshold of p<0.01 for significant differences to avoid type II error. Therefore, covariates that continued to differ at the p<0.01 threshold after IPTW were included as covariates in models of change in PTSD symptoms. We assessed the potential contribution of unmeasured confounding on our results by calculating E-values, which indicate the minimum strength of association on the risk ratio scale that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the exposure and the outcome, conditional on the measured covariates, to fully explain away a specific exposure-outcome association (Haneuse, VanderWeele, & Arterburn, 2019; VanderWeele & Ding, 2017).

Table 1:

VA Users with New Episodes of PTSD Care from 2004–2013, by Receipt of Psychotherapy Procedure Code

| Category | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Received Psychotherapy | Did Not Receive Psychotherapy | |

| Patient Characteristics, N | 731,520 | 647,513 | 84,007 |

| Age, M (SD)** | 49.9 (15.4) | 49.8 (15.2) | 50.8 (16.5) |

| Women, % (n)** | 8.5 (61,853) | 8.9 (57,409) | 5.3 (4,444) |

| Married, % (n) | 53.2 (389,262) | 53.0 (342,970) | 55.1 (46,292) |

| White Non-Hispanic, % (n)* | 62.6 (457,673) | 62.5 (404,774) | 63.0 (52,899) |

| OEF/OIF/OND Veteran, % (n)** | 28.5 (208,769) | 28.5 (184,246) | 29.2 (24,523) |

| Rural, % (n)** | 35.3 (258,177) | 34.8 (225,529) | 38.9 (32,648) |

| Combat Exposure, % (n)** | 32.8 (239,686) | 32.1 (208,007) | 37.7 (31,679) |

| Sexual Trauma while in Military, % (n)** | 9.2 (67,024) | 9.6 (62,388) | 5.5 (4,636) |

| VA Disability Level 70% or Greater, % (n) | 59.0 (431,632) | 58.9 (381,621) | 59.5 (50,011) |

| Charleson Comorbidity Index 1 or greater, % (n)** | 24.4 (178,575) | 24.3 (157,342) | 25.3 (21,233) |

| Psychotic Disorders, % (n)** | 5.7 (41,789) | 5.9 (38,243) | 4.2 (3,546) |

| Bipolar Mood Disorders, % (n)** | 7.2 (52,596) | 7.6 (49,128) | 4.1 (3,468) |

| Depressive Mood Disorders, % (n)** | 65.5 (478,763) | 67.2 (435,185) | 51.9 (43,578) |

| Non-PTSD Anxiety Disorders, % (n)** | 34.5 (252,107) | 35.8 (231,968) | 24.0 (20,139) |

| Traumatic Brain Injury, % (n)** | 8.6 (62,936) | 7.8 (56,844) | 7.3 (6,092) |

| Alcohol Use Disorders, % (n)** | 27.1 (198,166) | 28.1 (182,205) | 19.0 (15,961) |

| Opioid Use Disorders, % (n)** | 3.7 (27,175) | 4.0 (25,786) | 1.7 (1,389) |

| Other Drug Use Disorders, % (n)** | 19.7 (144,350) | 20.7 (134,050) | 12.3 (10,300) |

| Service Use Characteristics, N | 731,520 | 647,513 | 84,007 |

| Prior Psychotherapy Use (2 years), % (n)** | 45.9 (335,488) | 47.1 (305,132) | 36.1 (30,356) |

| Adequate Trial of EBA for PTSD, % (n)** | 31.4 (229,849) | 28.4 (207,632) | 26.5(22,217) |

| PTSD Outpatient Clinical Team Use (540 or 561), % (n)** | 34.9 (255,151) | 36.7 (237,541) | 21.0 (17,610) |

| Outpatient Mental Health Visits, M (SD)** | 12.6 (15.1) | 13.6 (15.6) | 4.3 (5.1) |

| Outpatient Substance Abuse Visits, M (SD)** | 3.0 (13.1) | 3.4 (13.8) | 0.4 (4.1) |

| Outpatient Primary Care Visits, M (SD)** | 3.5 (3.5) | 3.5 (3.5) | 2.9 (3.0) |

| Emergency Department Visit for Psychiatric Indication, % (n)** | 6.4 (46,616) | 6.8 (43,781) | 3.4 (2,835) |

| Acute Mental Health Inpatient Admission, % (n)** | 6.6 (48,531) | 7.2 (46,429) | 2.5 (2,102) |

| Residential PTSD Admission, % (n)** | 2.4 (17,278) | 2.6 (16,836) | 0.5 (442) |

| Residential Substance Abuse Admission, % (n)** | 2.7 (19,696) | 3.0 (19,464) | 0.3 (232) |

| Primary Therapist Characteristics, where known | |||

| Age, M (SD) | - | 50.8 (11.2) | - |

| Women, % (n) | - | 47.0 (304,190) | - |

| Psychologist, % (n) | - | 29.3 (189,719) | - |

| Social Worker, % (n) | - | 29.2 (189,056) | - |

| Nurse, % (n) | - | 9.0 (58,347) | - |

| Psychiatrist, % (n) | - | 25.7 (166,326) | - |

| Other, % (n) | - | 6.7 (43,374) | - |

| Prescribing Privileges, % (n) | - | 36.0 (233,108) | - |

| Percentage of Time Seeing PTSD Patients in Various Settings | - | - | - |

| PTSD Service Section (PCT or residential), M (SD) | - | 28.5 (37.5) | - |

| Substance Abuse Service Section, M (SD) | - | 5.7 (19.5) | - |

| Comorbid PTSD Substance Abuse Service Section, M (SD) | - | 0.2 (3.4) | - |

| General Mental Health Service Section, M (SD) | - | 54.7 (39.9) | - |

| Integrated Care Service Section, M (SD) | - | 6.5 (18.8) | - |

Note. VA=United States Department of Veterans Affairs; PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; M=mean, SD=standard deviation; OEF/OIF/OND=Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn

p<0.05

p<0.001

In addition to our pre/post measures, we performed a repeated measures model that included all PCL measurements between baseline and follow-up. We used a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) to account for both within-person and across-person variability. We compared changes in PTSD symptom during the time treatment was delivered, including a time by treatment interaction to measure the change in slope over time among the tree treatment groups. The model is weighted by the inverse of the propensity scores and adjusted for any unbalanced covariates (p<0.01). We performed data management in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and developed causal models in R version 3.5.0 (R core team). This included IPTW models created using the R twang package (Ridgeway, McCaffrey, Morral, Burgette, & Griffin, 2017), and models to detect unmeasured confounding using the R evalue package (Mathur, Ding, & VanderWeele, 2018).

Results

Of the 731,520 patients in our cohort, 88.6% (n=647,513) had at least one psychotherapy procedural code during their first year of PTSD treatment. Patients who did and did not receive a psychotherapy procedural code differed on almost all variables (Table 1). Most prominently, those who received a psychotherapy procedural code were more likely to be women, to have experienced sexual trauma while in the military, and to have comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses. At the same time, they were less likely to be rural or to have been exposed to combat. They also received other VA health services at higher levels, and importantly, 47.1% (n=305,132) also received a psychotherapy procedural code in the two years prior to their index PTSD diagnosis. Almost half of patients who received a psychotherapy procedural code saw a woman as their primary therapist, and patients most commonly saw a psychologist or social worker as their primary therapist. In over a third of cases, the primary therapist had prescription privileges, indicating that therapy could have been coded as part of medication management. Patients primary therapists generally spent most of their time in general mental health settings, followed by specialized PTSD settings.

In the overall cohort, use of any psychotherapy, whether classified using procedural codes or natural language processing, increased over the 10-year period of examination (Table 2). While the percentage of patients receiving at least one psychotherapy procedural code had little room for improvement, the difference between receipt of any psychotherapy as measured using procedural codes and as measured using NLP decreased from FY04–05 (86.0% versus 54.7%) to FY12–13 (90.2% versus 65.8%). At the same time, the mean number of psychotherapy encounters remained stable (9.3 versus 10.0). This indicates that despite persistence of procedural coding discrepancies, more patients with PTSD were actually receiving psychotherapy during administratively coded psychotherapy encounters by the end of the period of examination. Furthermore, there was a dramatic increase in the use of EBP for PTSD, from 0.7% in FY04–05 to 14.1% in FY12–13. The most common EBP modality was individual CPT-I, followed by CPT-G, and PE.

Table 2:

Psychotherapy Receipt in the in the Year Following Initial PTSD Diagnosis

| Fiscal Year | 2004–2005 | 2006–2007 | 2008–2009 | 2010–2011 | 2012–2013 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New PTSD Episodes | n=111,828 | n=128,652 | n=160,444 | n=168,771 | n=161,825 | 731,520 |

| Total Psychotherapy Encounters, M (SD) | 9.3 (14.1) | 8.8 (13.3) | 9.4 (13.7) | 10.1 (14.0) | 10.0 (13.7) | 9.6 (13.8) |

|

Any Receipt | ||||||

| Any Psychotherapy: Procedure Codes | 86.0% (96,138) | 86.8% (111,703) | 88.0% (141,227) | 90.3% (152,407) | 90.2% (146,038) | 88.5% (647,513) |

| Individual | 81.7% (91,337) | 82.8% (106,554) | 84.9% (136,279) | 87.3% (147,301) | 86.8% (140,415) | 85.0% (621,886) |

| Group | 32.0% (35,734) | 30.3% (39,042) | 29.3% (46,999) | 31.7% (53,426) | 33.5% (54,164) | 31.4% (229,365) |

| Any Psychotherapy: NLP | 54.7% (61,224) | 57.0% (73,393) | 60.7% (97,422) | 64.2% (108,317) | 65.8% (106,523) | 61.1% (446,879) |

| Individual | 43.6% (48,735) | 46.9% (60,329) | 52.0% (83,354) | 54.9% (92,691) | 56.5% (91,360) | 51.5% (376,469) |

| Group | 27.3% (30,478) | 26.6% (34,275) | 26.2% (42,047) | 29.0% (48,913) | 30.6% (49,559) | 28.1% (205,272) |

| Any EBP: NLP | 0.7% (773) | 2.5% (3,210) | 7.4% (11,940) | 11.1% (18,754) | 14.1% (22,756) | 7.9% (57,433) |

| Group Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.2% (257) | 0.7% (940) | 2.2% (3,587) | 3.9% (6,541) | 4.5% (7,203) | 2.5% (18,528) |

| Individual Prolonged Exposure | 0.1% (162) | 0.3% (350) | 1.6% (2,608) | 3.1% (5,192) | 3.6% (5,874) | 1.9% (14,186) |

| Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.4% (453) | 1.9% (2,431) | 4.8% (7,726) | 6.4% (10,726) | 8.6% (13,860) | 4.8% (35,196) |

Note. PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; EBP=Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD; NLP=Natural Language Processing

We then applied quality standards to psychotherapy receipt among the 54.1% (n=396,032) of patients initiating psychotherapy after their index PTSD diagnosis. This resulted in a decrease in the percentage of patients who met those standards as the standards became more stringent (Table 3). For example, while 86.5% received at least one procedural code for psychotherapy in their first year of treatment, only 13.8% received eight or more sessions (as measured using procedural codes) over the course of any 14-week period. Similarly, if we use NLP rather than procedural codes to classify psychotherapy receipt, the figure drops from 13.8% to 11.4%. If we then require that NLP indicates the sessions are EBP, the figure drops from 11.4% to 2.0%. Therefore, estimates of psychotherapy receipt appear to be highly dependent on both the restrictiveness of the quality standards and the content of the psychotherapy notes. Despite these caveats, quality as determined by all standards we applied improved over time during the period of examination (Appendix 1).

Table 3:

Psychotherapy Initiation in the Year Following Initial PTSD Diagnosis among 396,032 Patients with No Psychotherapy Encounters in the 2 Years Prior to PTSD Diagnosis, Fiscal Years 2004–2013; Mean of 7.8 (SD=10.8) psychotherapy encounters.

| Quality Standard | Any Receipt | 8+ Sessions | 8+ Sessions, Same Therapist | 8+ Sessions in 14 weeks, Same Therapist |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Psychotherapy: Procedure Codes | 86.5% (342,381) | 32.2% (127,381) | 23.3% (92,374) | 13.8% (54,608) |

| Individual | 82.7% (327,358) | 21.9% (86,704) | 14.6% (57,954) | 6.1% (24,050) |

| Group | 28.3% (112,152) | 12.6% (49,832) | 10.2% (40,346) | 7.9% (31,403) |

| Any Psychotherapy: NLP | 59.5% (235,706) | 21.8% (86,238) | 18.1% (71,789) | 11.4% (44,963) |

| Individual | 50.4% (199,543) | 11.4% (45,110) | 9.9% (39,182) | 4.6% (18,176) |

| Group | 25.0% (99,185) | 11.1% (44,024) | 8.9% (35,124) | 6.7% (26,468) |

| Any EBP: NLP | 7.7% (30,593) | 2.9% (11,353) | 2.5% (9,980) | 2.0% (8,058) |

| Group Cognitive Processing Therapy | 2.2% (8.815) | 0.8% (3,300) | 0.6% (2,226) | 0.5% (1,867) |

| Individual Prolonged Exposure | 2.1% (8,227) | 0.6% (2,440) | 0.6% (2,316) | 0.5% (1,913) |

| Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy | 4.7% (18,584) | 1.4% (5,375) | 1.3% (5,112) | 1.0% (4,005) |

Note. PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; EBP=Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD; NLP=Natural Language Processing. Yearly trends presented in Appendix 1.

A substantial number of patients from the FY08–13 cohort who met our increasingly restrictive quality standards had PCL measurement aligned with sessions 1 and 8 and were included in analyses comparing outcomes among patients who met increasingly strict quality standards. Among the 10,765 patients who had 8 or more sessions of EBP as measured using NLP, 19.1% (n=2,052) met our PCL-based inclusion criteria. Table 4 shows that there were few significant differences among patients who had 8 or more sessions of EBP with and without aligned PCL measurement. Furthermore, where differences were significant, the magnitude was small. After applying the IPTW procedure to balance covariates across quality standard groups, only one unbalanced variable remained (Appendix 2): days between baseline PCL and session 1. This unbalanced variable was used as a covariate in weighted analyses.

Table 4:

VA Users Initiating Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD and Completing 8 or More Sessions within a Year, FY 2008–2013, by Receipt of Aligned PTSD Checklist Measurement

| Category | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | With Aligned PCL Measurement | Without Aligned PCL Measurement | |

| Patient Characteristics, N | 10,765 | 2,052 | 8,713 |

| Age, M (SD)** | 47.3 (15.2) | 45.2 (15.2) | 47.8 (15.1) |

| Women, % (n) | 12.9 (1,390) | 13.8 (283) | 12.7 (1,107) |

| Married, % (n)* | 60.8 (6,547) | 62.8 (1,288) | 60.4 (5,259) |

| White Non-Hispanic, % (n) | 63.8 (6,871) | 62.3 (1,279) | 64.2 (5,592) |

| OEF/OIF/OND Veteran, % (n)** | 41.7 (4,490) | 50.3 (1,033) | 39.7 (3,457) |

| Rural, % (n) | 32.8 (3,529) | 31.6 (649) | 33.1 (2,880) |

| Combat Exposure, % (n) | 27.7 (2,983) | 27.0 (554) | 27.9 (2,429) |

| Sexual Trauma while in Military, % (n) | 13.2 (1,417) | 13.5 (277) | 13.1 (1,140) |

| VA Disability Level 70% or Greater, % (n) | 58.8 (6,334) | 60.2 (1,236) | 58.5 (5,098) |

| Charleson Comorbidity Index 1 or greater, % (n) | 12.6 (1,353) | 12.3 (253) | 12.6 (1,100) |

| Psychotic Disorders, % (n) | 1.9 (209) | 1.5 (31) | 2.0 (178) |

| Bipolar Mood Disorders, % (n) | 3.4 (363) | 3.4 (70) | 3.4 (293) |

| Depressive Mood Disorders, % (n)** | 66.3 (7,141) | 70.9 (1,455) | 65.3 (5,686) |

| Non-PTSD Anxiety Disorders, % (n)* | 37.9 (4,080) | 41.0 (841) | 37.2 (3,239) |

| Traumatic Brain Injury, % (n)** | 15.6 (1,681) | 18.6 (381) | 14.9 (1,300) |

| Alcohol Use Disorders, % (n)* | 24.6 (2,648) | 26.5 (544) | 24.2 (2,104) |

| Opioid Use Disorders, % (n) | 1.9 (207) | 2.1 (42) | 1.9 (165) |

| Other Drug Use Disorders, % (n) | 14.9 (1,607) | 13.8 (283) | 15.2 (1,324) |

| Service Use Characteristics, N | |||

| Adequate Trial of EBA for PTSD, % (n)** | 30.0 (3,227) | 33.7 (691) | 29.1 (2,536) |

| PTSD Outpatient Clinical Team Use (540 or 561), % (n)** | 67.5 (7,270) | 71.5 (1,467) | 66.6 (5,803) |

| Outpatient Mental Health Visits, M (SD)* | 28.6 (16.3) | 27.8 (14.7) | 28.8 (16.7) |

| Outpatient Substance Abuse Visits, M (SD) | 3.8 (12.3) | 4.2 (13.2) | 3.8 (12.0) |

| Outpatient Primary Care Visits, M (SD) | 3.3 (3.3) | 3.3 (3.1) | 3.3 (3.3) |

| Emergency Department Visit for Psychiatric Indication, % (n) | 7.7 (829) | 8.1 (166) | 7.6 (663) |

| Acute Mental Health Inpatient Admission, % (n) | 6.7 (722) | 6.9 (141) | 6.7 (581) |

| Residential PTSD Admission, % (n) | 8.4 (904) | 8.4 (173) | 8.4 (731) |

| Residential Substance Abuse Admission, % (n) | 2.4 (258) | 2.2 (46) | 2.4 (212) |

| Primary Therapist Characteristics, where known | |||

| Age, M (SD)** | 44.8 (10.9) | 43.6 (11.1) | 45.1 (10.8) |

| Women, % (n) | 66.4 (5,825) | 67.4 (1,126) | 66.2 (4,699) |

| Psychologist, % (n)** | 60.0 (6,450) | 65.3 (1,339) | 58.7 (5,111) |

| Social Worker, % (n)** | 32.8 (3,529) | 28.7 (588) | 33.8 (2,941) |

| Nurse, % (n)* | 2.2 (236) | 1.3 (26) | 2.4 (210) |

| Psychiatrist, % (n)* | 1.6 (175) | 0.8 (17) | 1.8 (158) |

| Other, % (n) | 3.4 (369) | 3.9 (80) | 3.3 (289) |

| Prescribing Privileges, % (n)* | 8.9 (961) | 7.6 (155) | 9.3 (806) |

| Percentage of Time Seeing PTSD Patients in Various Settings | - | - | - |

| PTSD Service Section (PCT or residential), M (SD)* | 56.2 (38.7) | 58.3 (38.6) | 55.6 (38.7) |

| Substance Abuse Service Section, M (SD) | 3.7 (13.5) | 3.5 (12.8) | 3.7 (13.6) |

| Comorbid PTSD Substance Abuse Service Section, M (SD)** | 0.4 (3.9) | 0.9 (5.9) | 0.3 (3.3) |

| General Mental Health Service Section, M (SD)* | 30.7 (34.7) | 28.6 (34.2) | 31.2 (34.8) |

| Integrated Care Service Section, M (SD) | 5.3 (16.1) | 5.1 (16.1) | 5.4 (16.1) |

Note. VA=United States Department of Veterans Affairs; PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; M=mean, SD=standard deviation; OEF/OIF/OND=Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn

p<0.05

p<0.001

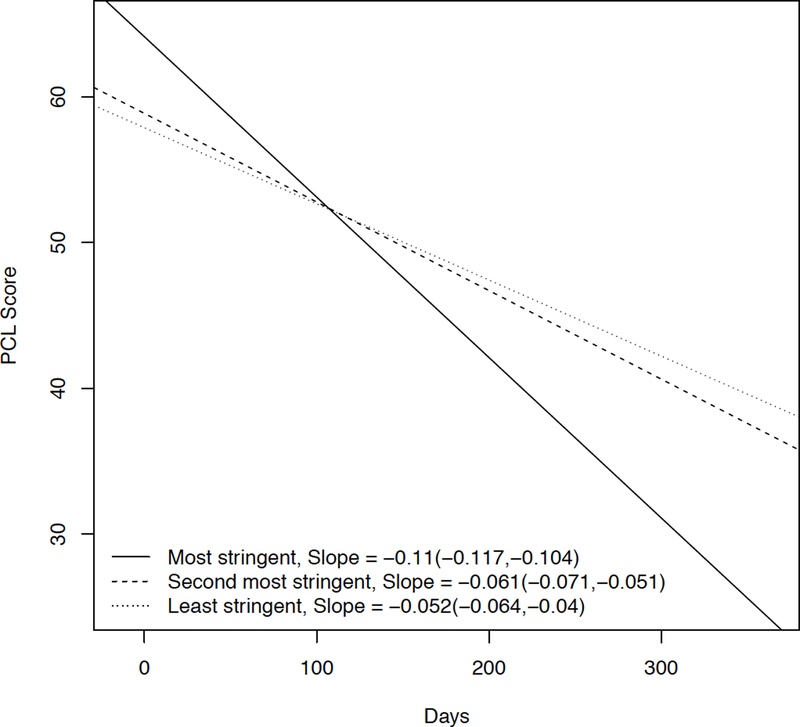

In pre/post causal analyses, the most stringent quality standard (8 EBP sessions with the same therapist within 14 weeks) was associated with significantly higher rates of loss of diagnosis (23.3% versus 13.8%; p=0.0004, e=2.78) and continuous improvement on the PCL (−9.3 versus −7.1; p=0.0101, e=1.60) than the least stringent standard (any 8 EBP sessions during the first year of treatment, but not the second most stringent quality standard (8 EBP sessions with the same therapist during the first year of treatment). However, the second most stringent quality standard was not significantly superior to the least stringent quality standard, indicating that across data sources, only the strictest definition of treatment adequacy was consistently associated with superior pre/post outcomes. The e-value findings indicate that it would take a very strong unmeasured confounder (relative risk of 2.78 or greater) to overturn the loss of diagnosis finding and a moderately strong unmeasured confounder (relative risk of 1.60 or greater) to overturn the continuous improvement on the PCL finding. Our GLMM approach supports this assessment (Figure 1). The rate of improvement in PCL score was best when using the most stringent treatment adequacy standard. Thus, requiring a quality standard of 8 or more sessions with the same therapist within 14 weeks was associated with both the greatest amount of pre/post change and the fastest rate of change.

Figure 1:

Repeated Measures Model of Change in Total PCL Score

Note. NLP=Natural Language Processing; EBP=Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Discussion

We found that psychotherapy for PTSD quality standards that more stringently reflect the underlying evidence were associated with superior outcomes in clinical practice. Thus, our work provides preliminary validity for an NLP-based quality measure comprising eight or more sessions of EBP, delivered by the same therapist, over the course of 14 weeks. The percentage of VA patients with new PTSD treatment episodes meeting this standard improved from 0.1% to 3.7% over a 10-year period marked by investment in mental health services from 2004 through 2013. This improvement is likely a reflection of the resources invested in the national implementation of EBP for PTSD. However, these findings highlight that while most patients initiating PTSD care in the VA did receive some psychotherapy in the initial year, the vast majority did not meet this quality standard. Thus, it is possible that many patients initiating care during this period would have benefited from more intensive treatment. This work shows that by examining the content of psychotherapy sessions, it is possible to avoid overestimating treatment quality, providing a more accurate baseline against which to measure the effect of improvement efforts. Regardless of how session content is measured in the future (e.g., NLP of note text versus the use of EBP-specific note templates), our work provides a basic framework for using the related data to develop an EBP for PTSD quality measure.

Our study addresses several gaps in the available research regarding quality measurement for PTSD treatment. First, few studies include clinical detail from chart notes, such as whether an EBP was delivered (Hepner et al., 2016). By using NLP, we were able to identify when an EBP was delivered for each person in the cohort and incorporate this information into our quality measures. Similarly, most measures of psychotherapy focus on access to care or quantifying the number of visits, and often this is due to limited data on diagnosis, severity of illness, treatment history, and the content and number of visits (Brown, Scholle, & Azur, 2014). Availablity of these additional factors in our dataset allowed us to perfom causal analyses in order to determine whether various definitions of quality were associated with improved PTSD outcomes.

There are several limitations to our study. First, we did not examine a range of cutoffs for the required number of sessions and for number of weeks over which those sessions should be delivered. Examining multiple cutoffs would have created an unmanageable number of comparisons, across which we would have had to balance our covariates to avoid bias in causal analyses. Thus, we used a single standard for number of sessions supported by prior research and a single standard for treatment density that has been used operationally in the VA. Future research should address the question of the minimal number of sessions for an adequate treatment and the maximum amount of time over which those sessions should be delivered. Second, we did not compare EBP to non-EBP. Extensive available research already demonstrates that trauma-focused evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD is associated with superior outcomes to non-specific psychotherapy in the treatment of PTSD (The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Work Group, 2017). While additional “real world” studies about the clinical effectiveness of EBPs for PTSD (compared to other treatments) may be warranted, our work is not designed to make those inferences. Fourth, there were several differences in potentially important patient and therapist characteristics among those meeting various quality standards. However, analyses controlled for key differences and our sensitivity analyses indicate that unmeasured confounding is unlikely to overturn our outcome. Finally, even NLP of psychotherapy notes to detect EBP use is a proxy measure of EBP delivery. Without video, we cannot be sure what happened during psychotherapy sessions. However, we believe that our NLP method is the closet possible approximation to study EBP implementation in the VA during the critical time period examined.

In summary, this research demonstrates that a theoretically-oriented approach to quality measurement can be used to create the basic structure of a psychotherapy for PTSD quality measure. While our work captures the receipt of effective and timely treatment, our measure of quality is incomplete. Health systems should also seek to provide PTSD care that is safe, patient-centered, equitable, and efficient (Pincus et al., 2007).

Table 5:

Inverse Propensity of Treatment Weighted Comparison of PTSD Symptomatic Outcomes for Patients Completing 8 or More Sessions of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD with Aligned PTSD Checklist Measurement, FY 2008–2013, by Quality Standard

| Quality Standard | (A) 8 | (B) 8 ST | (C) 8 ST 14W | A versus B | A versus C | B versus C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=303 | n=549 | n=1,200 | P | E | P | E | P | E | |

| Baseline PCL, mean (SD) | 64.2 (11.0) | 63.6 (10.1) | 63.6 (10.0) | 0.5383 | 0.4417 | 0.9994 | |||

| Change in PCL, mean (SD) | −7.1 (13.2) | −8.6 (14.2) | −9.3 (13.0) | 0.1627 | 1.45 | 0.0101 | 1.60 | 0.3757 | 1.26 |

| 10-Poing Drop on PCL plus LOD, % (n) | 13.8 (43) | 21.4 (115) | 23.3 (285) | 0.0274 | 2.47 | 0.0004 | 2.77 | 0.4346 | 1.40 |

Note. E-value indicates the he minimum strength of association on the risk ratio scale that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the exposure and the outcome, conditional on the measured covariates, to fully explain away a specific exposure-outcome association; LOD=loss of diagnosis; BOLD=p<0.0167.

Acknowledgments

AVA Health Services Research & Development Career Development Award to Dr. Shiner (CDA11–263) funded the development of this cohort. A DoD Joint Warfighter Medical Research Program Award to Dr. Maguen (JW140056) funded the refinement of our strategy to measure evidence-based psychotherapy, which was originally supported with a VA New England Early Career Development Award to Dr. Shiner (V1CDA10–03). A DoD Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program Award to Dr. Shiner (PR160206) funded the development of our strategy to leverage patient-reported outcomes data.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Department of Defense.

APPENDIX 1:

Psychotherapy Initiation in the Year Following Initial PTSD Diagnosis among Patients with No Psychotherapy Encounters in the 2 Years Prior to PTSD Diagnosis, by Punitive Quality Standards

| Fiscal Years | 2004–2005 | 2006–2007 | 2008–2009 | 2010–2011 | 2012–2013 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New PTSD Episodes | n=58,061 | n=69,640 | n=90,269 | n=92,515 | n=85,547 | 396,032 |

| Total Psychotherapy Encounters, M (SD) | 8.0 (11.6) | 7.5 (10.8) | 7.7 (10.8) | 8.0 (10.7) | 7.9 (10.5) | 7.8 (10.8) |

|

Any Receipt | ||||||

| Any Psychotherapy: Procedural Codes | 84.4% (49,022) | 85.2% (59,368) | 85.9% (77,548) | 88.1% (81,487) | 87.6% (74,956) | 86.5% (342,381) |

| Individual | 79.6% (46,199) | 81.0% (56,410) | 82.6% (74,606) | 84.8% (78,430) | 83.8% (71,713) | 82.7% (327,358) |

| Group | 30.2% (17,540) | 28.3% (19,714) | 26.1% (23,591) | 28.0% (25,933) | 29.7 (25,374) | 28.3% (112,152) |

| Any Psychotherapy: NLP | 54.2% (31,496) | 56.8% (39,537) | 59.4% (53,589) | 61.8% (57,182) | 63.0% (53,902) | 59.5% (235,706) |

| Individual | 43.6% (25,307) | 47.4% (32,978) | 51.2% (46,204) | 52.9% (48,939) | 53.9% (46,115) | 50.4% (199,543) |

| Group | 25.6% (14,835) | 24.6% (17,103) | 23.1% (20,885) | 25.4% (23,540) | 26.7% (22,822) | 25.0% (99,185) |

| Any EBP: NLP | 0.6% (373) | 2.7% (1,884) | 7.7% (6,939) | 10.7% (9,855) | 13.5% (11,542) | 7.7% (30,593) |

| Group Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.2% (104) | 0.6% (436) | 2.0% (1,801) | 3.4% (3,160) | 3.9% (3,314) | 2.2% (8.815) |

| Individual Prolonged Exposure | 0.1% (82) | 0.3% (224) | 1.9% (1,687) | 3.2% (2,946) | 3.8% (3,288) | 2.1% (8,227) |

| Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.4% (236) | 2.1% (1,449) | 4.9% (4,454) | 6.0% (5,545) | 8.1% (6,900) | 4.7% (18,584) |

|

Eight or More Sessions | ||||||

| Any Psychotherapy: Procedural Codes | 30.9% (17,926) | 29.8% (20,757) | 32.0% (28,864) | 33.6% (31,079) | 33.6% (28,755) | 32.2% (127,381) |

| Individual | 18.1% (10,506) | 19.0% (13,214) | 22.9% (20,635) | 23.5% (21,741) | 24.1% (20,608) | 21.9% (86,704) |

| Group | 15.4% (8,931) | 13.1% (9,121) | 11.5% (10,371) | 12.4% (11,479) | 11.6% (9,930) | 12.6% (49,832) |

| Any Psychotherapy: NLP | 19.3% (11,179) | 19.6% (13,656) | 21.3% (19,237) | 23.4% (21,603) | 24.0% (20,563) | 21.8% (86,238) |

| Individual | 7.0% (4,048) | 8.8% (6,150) | 11.9% (10,745) | 12.8% (11,864) | 14.4% (12,303) | 11.4% (45,110 |

| Group | 12.6% (7,331) | 11.4% (7,927) | 10.3% (9,284) | 11.4% (10,519) | 10.5% (8,963) | 11.1% (44,024) |

| Any EBP: NLP | 0.2% (94) | 0.7% (494) | 2.6% (2,326) | 4.4% (4,060) | 5.1% (4,379) | 2.9% (11,353) |

| Group Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.0% (23) | 0.2% (109) | 0.6% (579) | 1.4% (1,337) | 1.5% (1,252) | 0.8% (3,300) |

| Individual Prolonged Exposure | 0.0% (11) | 0.0% (31) | 0.5% (493) | 1.1% (991) | 1.1% (914) | 0.6% (2,440) |

| Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.1% (63) | 0.5% (372) | 1.4% (1,226) | 1.8% (1,622) | 2.4% (2,092) | 1.4% (5,375) |

|

Eight or More Sessions with the Same Therapist | ||||||

| Any Psychotherapy: Procedural Codes | 23.1% (13,389) | 22.0% (15,288) | 22.9% (20,635) | 24.0% (22,204) | 24.4% (20,858 | 23.3% (92,374) |

| Individual | 11.8% (6,841) | 12.5% (8,697) | 15.2% (13,717) | 15.6% (14,397) | 16.7% (14,302) | 14.6% (57,954) |

| Group | 12.7% (7,367) | 10.9% (7,595) | 9.2% (8,317) | 10.0% (9,237) | 9.2% (7,830) | 10.2% (40,346) |

| Any Psychotherapy: NLP | 15.8% (9,167) | 16.4% (11,389) | 17.8% (16,028) | 19.7% (18,189) | 19.9% (17,016) | 18.1% (71,789) |

| Individual | 6.0% (3,456) | 7.5% (5,216) | 10.3% (9,302) | 11.3% (10,464) | 12.6% (10,744) | 9.9% (39,182) |

| Group | 10.2% (5,941) | 9.4% (6,528) | 8.2% (7,377) | 9.1% (8,379) | 8.1% (6,899) | 8.9% (35,124) |

| Any EBP: NLP | 0.1% (78) | 0.7% (458) | 2.3% (2,042) | 3.9% (3,562) | 4.5% (3,840) | 2.5% (9,980) |

| Group Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.0% (11) | 0.1% (74) | 0.4% (369) | 1.0% (924) | 1.0% (848) | 0.6% (2,226) |

| Individual Prolonged Exposure | 0.0% (11) | 0.0% (31) | 0.5% (460) | 1.0% (952) | 1.0% (862) | 0.6% (2,316) |

| Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.1% (55) | 0.5% (361) | 1.3% (1,149) | 1.7% (1,549) | 2.3% (1,998) | 1.3% (5,112) |

|

Eight or More Sessions in 14 Weeks with the Same Therapist | ||||||

| Any Psychotherapy: Procedural Codes | 13.2% (7,678) | 12.6% (8,747) | 12.7% (11,437) | 14.5% (13,390) | 15.6% (13,356) | 13.8% (54,608) |

| Individual | 3.6% (2,074) | 4.3% (2,971) | 5.9% (5,345) | 6.8% (6,300) | 8.6% (6,300) | 6.1% (24,050) |

| Group | 9.6% (5,584) | 8.4% (5,853 | 7.0% (6,304) | 7.9% (7,297) | 7.4% (6,365) | 7.9% (31,403) |

| Any Psychotherapy: NLP | 9.5% (5,497) | 10.0% (6,962) | 10.6% (9,540) | 12.7% (11,763) | 13.1% (11,201) | 11.4% (44,963) |

| Individual | 2.0% (1,154) | 2.8% (1,983) | 4.5% (4,068) | 5.6% (5,176) | 6.8% (5,795) | 4.6% (18,176) |

| Group | 7.2% (4,209) | 7.0% (4,863) | 6.0% (5,440) | 7.1% (6,534) | 6.3% (5,422) | 6.7% (26,468) |

| Any EBP: NLP | 0.1% (62) | 0.5% (359) | 1.7% (1,557) | 3.2% (2,924) | 3.7% (3,156) | 2.0% (8,058) |

| Group Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.0% (8) | 0.1% (61) | 0.3% (302) | 0.8% (777) | 0.8% (719) | 0.5% (1,867) |

| Individual Prolonged Exposure | 0.0% (9) | 0.0% (22) | 0.4% (366) | 0.9% (801) | 0.8% (715) | 0.5% (1,913) |

| Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy | 0.1% (44) | 0.4% (279) | 0.9% (833) | 1.3% (1,245) | 1.9% (1,604) | 1.0% (4,005) |

Note. PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; EBP=Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD; NLP=Natural Language Processing

Appendix 2:

Raw and Weighted Covariates for Comparisons of Quality Standards for Patients Receiving 8 or More Sessions of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD and Aligned PCL Measurement, FY 2008–2013

| Raw Data | Weighted Data | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics, N | (A) 8 n=303 | (B) 8 ST n=549 | (C) 8 14W ST n=1,200 | p value | (A) 8 n=303 | (B) 8 ST n=549 | (C) 8 14W ST n=1,200 | p value |

| Baseline PCL, M (SD) | 64.9 (9.9) | 63.2 (9.6) | 63.5 (9.8) | 0.041 | 64.2 (11.0) | 63.6 (10.1) | 63.6 (10.0) | 0.735 |

| Days Between Baseline PCL and Session 1, M (SD) | 2.4 (15.5) | 6.9 (23.0) | 0.8 (6.0) | <0.001 | 3.1 (22.7) | 2.8 (10.4) | 1.1 (8.1) | 0.002 |

| Days Between Follow-Up PCL and Session 8 M (SD) | 0.2 (5.8) | −1.9 (13.7) | 0.3 (5.8) | <0.001 | 0.2 (7.0) | −0.4 (7.3) | 0.2 (6.4) | 0.230 |

| Fiscal years 2008–2009 | 5.3 (16) | 7.7 (42) | 5.7 (68) | 0.220 | 6.3 (16) | 7.2 (42) | 6.1 (68) | 0.678 |

| Fiscal years 2010–2011 | 37.3 (113) | 35.5 (195) | 39.4 (473) | 0.284 | 36.3 (113) | 36.1 (195) | 39.1 (473) | 0.468 |

| Fiscal years 2012–2013 | 57.4 (174) | 56.8 (312) | 54.9 (659) | 0.625 | 57.4 (174) | 56.6 (312) | 54.9 (659) | 0.683 |

| Age, M (SD) | 47.2 (14.6) | 42.8 (14.7) | 45.8 (15.5) | <0.001 | 46.3 (16.4) | 16.3 (44.6) | 45.4 (15.4) | 0.326 |

| Women, % (n) | 9.6 (29) | 14.6 (80) | 14.5 (174) | 0.070 | 13.6 (29) | 14.4 (80) | 14.3 (174) | 0.963 |

| Married, % (n) | 68.6 (208) | 60.3 (331) | 62.4 (749) | 0.050 | 68.1 (208) | 61.8 (331) | 62.5 (749) | 0.252 |

| White Non-Hispanic, % (n) | 48.2 (146) | 62.7 (344) | 65.8 (789) | <0.001 | 55.3 (146) | 62.0 (344) | 63.8 (789) | 0.053 |

| OEF/OIF/OND Veteran, % (n) | 46.9 (142) | 55.2 (303) | 49.0 (588) | 0.024 | 48.8 (142) | 49.0 (303) | 50.2 (588) | 0.877 |

| Rural, % (n) | 32.3 (98) | 33.2 (182) | 30.8 (369) | 0.580 | 30.5 (98) | 33.6 (182) | 30.5 (369) | 0.462 |

| Combat Exposure, % (n) | 28.7 (87) | 27.0 (148) | 26.6 (319) | 0.757 | 30.2 (87) | 25.7 (148) | 27.0 (319) | 0.466 |

| Sexual Trauma while in Military, % (n) | 9.2 (28) | 12.4 (68) | 15.1 (181) | 0.020 | 12.8 (28) | 12.3 (68) | 14.8 (181) | 0.358 |

| VA Disability Level 70% or Greater, % (n) | 65.3 (198) | 62.7 (344) | 57.8 (694) | 0.023 | 62.1 (198) | 61.8 (344) | 58.5 (694) | 0.337 |

| Charleson Comorbidity Index 1 or greater, % (n) | 15.8 (48) | 10.2 (56) | 12.4 (149) | 0.056 | 14.8 (48) | 11.1 (56) | 11.9 (149) | 0.355 |

| Psychotic Disorders, % (n) | 1.0 (3) | 1.6 (9) | 1.6 (19) | 0.721 | 0.4 (3) | 1.5 (9) | 1.6 (19) | 0.133 |

| Bipolar Mood Disorders, % (n) | 3.6 (11) | 3.1 (17) | 3.5 (42) | 0.888 | 5.3 (11) | 3.0 (17) | 3.5 (42) | 0.382 |

| Depressive Mood Disorders, % (n) | 68.3 (207) | 71.6 (393) | 71.3 (855) | 0.555 | 68.6 (207) | 72.1 (393) | 71.5 (855) | 0.610 |

| Non-PTSD Anxiety Disorders, % (n) | 43.6 (132) | 41.3 (227) | 40.2 (482) | 0.550 | 42.1 (132) | 40.1 (227) | 40.0 (482) | 0.833 |

| Traumatic Brain Injury, % (n) | 17.2 (52) | 22.8 (125) | 17.0 (204) | 0.013 | 17.8 (52) | 20.7 (125) | 17.6 (204) | 0.291 |

| Alcohol Use Disorders, % (n) | 28.4 (86) | 27.0 (148) | 25.8 (310) | 0.643 | 24.8 (86) | 27.9 (148) | 25.8 (310) | 0.594 |

| Opioid Use Disorders, % (n) | 2.3 (7) | 2.0 (11) | 2.0 (24) | 0.940 | 1.6 (7) | 2.0 (11) | 2.0 (24) | 0.901 |

| Other Drug Use Disorders, % (n) | 14.9 (45) | 13.8 (76) | 13.5 (162) | 0.830 | 12.1 (45) | 13.0 (76) | 13.3 (162) | 0.863 |

| Adequate Trial of Evidence-Based Antidepressant for PTSD, % (n) | 41.3 (125) | 33.2 (182) | 32.0 (384) | 0.009 | 37.3 (125) | 33.0 (182) | 32.5 (384) | 0.363 |

| PTSD Outpatient Clinical Team Use (540 or 561), % (n) | 84.5 (256) | 71.2 (391) | 68.3 (820) | <0.001 | 78.3 (256) | 71.8 (391) | 70.4 (820) | 0.098 |

| Outpatient Mental Health Visits, M (SD) | 31.7 (16.3) | 27.6 (14.2) | 26.9 (14.4) | <0.001 | 29.0 (15.5) | 27.7 (15.3) | 27.3 (14.8) | 0.228 |

| Outpatient Substance Abuse Visits, M (SD) | 5.3 (13.9) | 3.8 (15.3) | 4.1 (11.9) | 0.256 | 3.6 (9.8) | 3.9 (16.7) | 4.1 (12.0) | 0.804 |

| Outpatient Primary Care Visits, M (SD) | 3.8 (3.5) | 3.1 (2.5) | 3.2 (3.1) | 0.005 | 3.3 (3.2) | 3.2 (2.9) | 3.2 (3.2) | 0.752 |

| Emergency Department Visit for Psychiatric Indication, % (n) | 8.3 (25) | 7.1 (39) | 8.5 (102) | 0.607 | 6.9 (25) | 7.1 (39) | 8.5 (102) | 0.510 |

| Acute Mental Health Inpatient Admission, % (n) | 6.3 (19) | 7.8 (43) | 6.6 (79) | 0.572 | 5.0 (19) | 7.5 (43) | 6.5 (79) | 0.426 |

| Residential PTSD Admission, % (n) | 15.8 (48) | 7.5 (41) | 7.0 (84) | <0.001 | 9.8 (48) | 8.2 (41) | 7.6 (84) | 0.432 |

| Residential Substance Abuse Admission, % (n) | 4.6 (14) | 1.1 (6) | 2.2 (26) | 0.004 | 2.4 (14) | 1.1 (6) | 2.2 (26) | 0.241 |

| Primary Therapist Characteristics, where known | ||||||||

| Age, M (SD) | 44.1 (12.3) | 43.3 (11.0) | 43.5 (10.9) | 0.664 | 43.1 (14.3) | 43.7 (12.9) | 43.4 (12.6) | 0.861 |

| Women, % (n) | 44.2 (134) | 60.5 (332) | 55.0 (660) | <0.001 | 64.7 (134) | 68.5 (332) | 68.5 (660) | 0.540 |

| Psychologist, % (n) | 65.7 (199) | 67.8 (372) | 64.0 (768) | 0.327 | 69.9 (199) | 66.5 (372) | 65.2 (768) | 0.395 |

| Social Worker, % (n) | 24.1 (73) | 27.0 (148) | 30.6 (367) | 0.046 | 25.2 (73) | 28.0 (148) | 29.5 (367) | 0.410 |

| Nurse, % (n) | 0.3 (1) | 1.1 (6) | 1.6 (19) | 0.199 | 0.2 (1) | 1.3 (6) | 1.5 (19) | 0.102 |

| Psychiatrist, % (n) | 0.7 (2) | 1.1 (6) | 0.8 (9) | 0.720 | 0.7 (2) | 1.2 (6) | 0.8 (9) | 0.683 |

| Other, % (n) | 9.2 (28) | 3.1 (17) | 2.9 (35) | <0.001 | 4.1 (28) | 3.0 (17) | 3.0 (35) | 0.510 |

| Prescribing Privileges, % (n) | 5.6 (17) | 7.8 (43) | 7.9 (95) | 0.379 | 6.5 (17) | 7.7 (43) | 7.7 (95) | 0.813 |

| Percentage of time in PTSD Service, M (SD) | 72.0 (33.7) | 57.5 (38.0) | 55.2 (39.2) | <0.001 | 63.8 (45.6) | 58.7 (41.2) | 57.9 (38.5) | 0.111 |

| Percentage of time in Substance Abuse Service, M (SD) | 3.4 (13.2) | 3.2 (10.7) | 3.7 (13.5) | 0.736 | 2.6 (9.5) | 3.0 (12.0) | 3.5 (12.3) | 0.338 |

| Percentage of time in PTSD-Substance Abuse Service, M (SD) | 1.1 (6.3) | 1.0 (6.5) | 0.8 (5.4) | 0.505 | 0.8 (4.0) | 0.8 (5.6) | 0.8 (6) | 0.973 |

| Percentage of time in General Mental Health Service, M (SD) | 17.5 (27.8) | 29.1 (33.8) | 31.2 (35.3) | <0.001 | 24.8 (41.4) | 28.6 (35.9) | 29.2 (34.0) | 0.245 |

| Percentage of time in Integrated Care Service, M (SD) | 3.5 (12.6) | 5.8 (17.4) | 5.3 (16.2) | 0.120 | 4.5 (17.5) | 5.5 (17.2) | 5.0 (15.8) | 0.735 |

Note. PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, PCL=PTSD Checklist, 8=eight sessions of evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP), 8 ST=eight sessions of EBP with the same the same psychotherapist, 8 14W S=eight sessions with the same therapist within 14 weeks, OEF/OIF/OND=Operations Enduring Freedom/Iraqi Freedom/New Dawn

References

- Adair CE, McDougall GM, Mitton CR, Joyce AS, Wild TC, Gordon A, … Beckie A. (2005). Continuity of care and health outcomes among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv, 56(9), 1061–1069. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision: DSM-IV-TR. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Scholle SH, & Azur M. (2014). Strategies for Measuring the Quality of Psychotherapy: A White Paper to Inform Measure Development and Implementation. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research; Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/strategies-measuring-quality-psychotherapy-white-paper-inform-measure-development-and-implementation. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, & Wachter RM (2010). Accountability measures--using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med, 363(7), 683–688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1002320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cully JA, Tolpin L, Henderson L, Jimenez D, Kunik ME, & Petersen LA (2008). Psychotherapy in the Veterans Health Administration: Missed Opportunities? Psychol Serv, 5(4), 320–331. doi: 10.1037/a0013719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. (1997). The quality of care. How can it be assessed? 1988. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 121(11), 1145–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SA, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, & Yadin E. (2005). Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol, 73(5), 953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, & Rothbaum BO (2007). Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Lowry P, & Ruzek J. (2010). VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for the management of post-traumatic stress Retrieved from www.healthquality.va.gov

- Galovski TE, Blain LM, Mott JM, Elwood L, & Houle T. (2012). Manualized therapy for PTSD: flexing the structure of cognitive processing therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol, 80(6), 968–981. doi: 10.1037/a0030600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Chou SP, Saha TD, Jung J, Zhang H, … Grant BF (2016). The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 51(8), 1137–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1208-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haagen JF, Smid GE, Knipscheer JW, & Kleber RJ (2015). The efficacy of recommended treatments for veterans with PTSD: A metaregression analysis. Clin Psychol Rev, 40, 184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haneuse S, VanderWeele TJ, & Arterburn D. (2019). Using the E-Value to Assess the Potential Effect of Unmeasured Confounding in Observational Studies. JAMA, 321(6), 602–603. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepner KA, Sloss EM, Roth CR, Krull H, Paddock SM, Moen S, Timmer MT, & Pincus HA (2016). Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression in the Military Health System: Phase I Report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes ED, Rosenheck RA, Desai R, & Fontana AF (2012). Recent trends in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental disorders in the VHA. Psychiatr Serv, 63(5), 471–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowka DW, Marx BP, Gates MA, Litman HJ, Ranganathan G, Rosen RC, & Keane TM (2014). PTSD diagnostic validity in Veterans Affairs electronic records of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Consult Clin Psychol, 82(4), 569–579. doi: 10.1037/a0036347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard KI, Kopta SM, Krause MS, & Orlinsky DE (1986). The dose-effect relationship in psychotherapy. Am Psychol, 41(2), 159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hripcsak G, & Wilcox A. (2002). Reference standards, judges, and comparison subjects: roles for experts in evaluating system performance. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 9(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt NE, Mott JM, Miles SR, Arney J, Cully JA, & Stanley MA (2015). Veterans’ perspectives on initiating evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Trauma, 7(6), 539–546. doi: 10.1037/tra0000035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Cusack K, Forneris CA, Wilkins TM, Sonis J, Middleton JC, … Gaynes BN (2013) Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Rockville (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, & Cross G. (2014). From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Am Psychol, 69(1), 19–33. doi: 10.1037/a0033888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, & Polusny MA (2016). Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychol Trauma, 8(1), 107–114. doi: 10.1037/tra0000065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussman MJ (2008). VHA Handbook 1160.01: Uniform Mental Helath Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics. Washington, D.C.: Department of Veterans Affairs; Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=1762. [Google Scholar]

- Lamp K, Maieritch KP, Winer ES, Hessinger JD, & Klenk M. (2014). Predictors of treatment interest and treatment initiation in a VA outpatient trauma services program providing evidence-based care. J Trauma Stress, 27(6), 695–702. doi: 10.1002/jts.21975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MW, Plagge JM, Marsiglio MC, & Dobscha SK (2016). Clinician Documentation on Receipt of Trauma-Focused Evidence-Based Psychotherapies in a VA PTSD Clinic. J Behav Health Serv Res, 43(1), 71–87. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9372-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Madden E, Patterson OV, DuVall SL, Goldstein LA, Burkman K, & Shiner B. (2018). Measuring Use of Evidence Based Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Large National Healthcare System. Adm Policy Ment Health. doi: 10.1007/s10488-018-0850-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur MB, Ding P, & VanderWeele TJ (2018). Package ‘EValue’: Sensitivity Analyses for Unmeasured Confounding in Observational Studies and Meta-Analyses. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/EValue/EValue.pdf

- McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA, Almirall D, Slaughter ME, Ramchand R, & Burgette LF (2013). A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Stat Med, 32(19), 3388–3414. doi: 10.1002/sim.5753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meystre SM, Savova GK, Kipper-Schuler KC, & Hurdle JF (2008). Extracting information from textual documents in the electronic health record: a review of recent research. Yearb Med Inform, 128–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Gradus JL, Young-Xu Y, Schnurr PP, Price JL, & Schumm JA (2008). Change in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: do clinicians and patients agree? Psychol Assess, 20(2), 131–138. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JM, Hundt NE, Sansgiry S, Mignogna J, & Cully JA (2014). Changes in psychotherapy utilization among veterans with depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Psychiatr Serv, 65(1), 106–112. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JM, Mondragon S, Hundt NE, Beason-Smith M, Grady RH, & Teng EJ (2014). Characteristics of U.S. veterans who begin and complete prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. J Trauma Stress, 27(3), 265–273. doi: 10.1002/jts.21927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JM, Stanley MA, Street RL Jr., Grady RH, & Teng EJ (2014). Increasing engagement in evidence-based PTSD treatment through shared decision-making: a pilot study. Mil Med, 179(2), 143–149. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, & Grant BF (2011). Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord, 25(3), 456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus HA, Page AE, Druss B, Appelbaum PS, Gottlieb G, & England MJ (2007). Can psychiatry cross the quality chasm? Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance use conditions. Am J Psychiatry, 164(5), 712–719. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, & Chard KM (2017). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD : a comprehensive manual. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, & Feuer CA (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. J Consult Clin Psychol, 70(4), 867–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Wachen JS, Mintz J, Young-McCaughan S, Roache JD, Borah AM, … Peterson AL (2015). A randomized clinical trial of group cognitive processing therapy compared with group present-centered therapy for PTSD among active duty military personnel. J Consult Clin Psychol, 83(6), 1058–1068. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway G, McCaffrey DF, Morral AR, Burgette LF, & Griffin BA (2017). Toolkit for Weghting and Analysis of Nonequivalent Groups: A Tutorial for the TWANG Package. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CS, Matthieu MM, Wiltsey Stirman S, Cook JM, Landes S, Bernardy NC, … Watts BV (2016). A Review of Studies on the System-Wide Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Veterans Health Administration. Adm Policy Ment Health, 43(6), 957–977. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0755-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck RA, & Fontana AF (2007). Recent trends In VA treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental disorders. Health Aff (Millwood), 26(6), 1720–1727. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, & Lunney CA (2016). Symptom Benchmarks of Improved Quality of Life in Ptsd. Depress Anxiety, 33(3), 247–255. doi: 10.1002/da.22477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Maguen S, Cohen B, Gima KS, Metzler TJ, Ren L, … Marmar CR (2010). VA mental health services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the first year of receiving new mental health diagnoses. J Trauma Stress, 23(1), 5–16. doi: 10.1002/jts.20493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, Bateman D, Young-Xu Y, Zayed M, Harmon AL, Pomerantz A, & Watts BV (2012). Comparing the stability of diagnosis in full vs. partial posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis, 200(6), 520–525. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318257c6da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, D’Avolio LW, Nguyen TM, Zayed MH, Watts BV, & Fiore L. (2012). Automated classification of psychotherapy note text: implications for quality assessment in PTSD care. J Eval Clin Pract, 18(3), 698–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01634.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, D’Avolio LW, Nguyen TM, Zayed MH, Young-Xu Y, Desai RA, … Watts BV (2013). Measuring use of evidence based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Adm Policy Ment Health, 40(4), 311–318. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0421-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, Drake RE, Watts BV, Desai RA, & Schnurr PP (2012). Access to VA services for returning veterans with PTSD. Mil Med, 177(7), 814–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, Leonard Westgate C, Bernardy NC, Schnurr PP, & Watts BV (2017). Trends in Opioid Use Disorder Diagnoses and Medication Treatment Among Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Dual Diagn, 13(3), 201–212. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2017.1325033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, Leonard Westgate C, Harik JM, Watts BV, & Schnurr PP (2016). Effect of Patient-Therapist Gender Match on Psychotherapy Retention Among United States Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Adm Policy Ment Health. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0761-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, Leonard Westgate C, Simiola V, Thompson R, Schnurr PP, & Cook JM (2018). Measuring Use of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD in VA Residential Treatment Settings with Clinician Survey and Electronic Medical Record Templates. Mil Med. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, Westgate CL, Bernardy NC, Schnurr PP, & Watts BV (2017). Anticonvulsant Medication Use in Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 78(5), e545–e552. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, Westgate CL, Gui J, Maguen S, Young-Xu Y, Schnurr PP, & Watts BV (2018). A Retrospective Comparative Effectiveness Study of Medications for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Routine Practice. J Clin Psychiatry, 79(5). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoont MR, Murdoch M, Hodges J, & Nugent S. (2010). Treatment receipt by veterans after a PTSD diagnosis in PTSD, mental health, or general medical clinics. Psychiatr Serv, 61(1), 58–63. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada RK, Bohnert KM, Ganoczy D, & Pfeiffer PN (2018). Documentation of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy and Care Quality for PTSD in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Adm Policy Ment Health, 45(3), 353–361. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0828-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada RK, Pfeiffer PN, Rauch SAM, Ganoczy D, & Bohnert KM (2018). Factors associated with the receipt of documented evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD in VA. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 54, 12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart EA (2010). Matching methods for casual inference: a review and a look forward. Statistical Science, 25(1), 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Work Group. (2017). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder. Washington, DC: United States Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense. [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Greenberg G, Harris AH, Tavakoli S, Kearney L, McCarthy J, … Schohn M. (2013). VHA mental health information system: applying health information technology to monitor and facilitate implementation of VHA Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook requirements. Med Care, 51(3 Suppl 1), S29–36. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827da836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk PW, Yoder M, Grubaugh A, Myrick H, Hamner M, & Acierno R. (2011). Prolonged exposure therapy for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: an examination of treatment effectiveness for veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. J Anxiety Disord, 25(3), 397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, & Forster AJ (2010). The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract, 16(5), 947–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, & Ding P. (2017). Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med, 167(4), 268–274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner TH, Sinnott P, & Siroka AM (2011). Mental health and substance use disorder spending in the Department of Veterans Affairs, fiscal years 2000–2007. Psychiatr Serv, 62(4), 389–395. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.4.pss6204_0389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts BV, Schnurr PP, Mayo L, Young-Xu Y, Weeks WB, & Friedman MJ (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 74(6), e541–550. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r08225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman BS, Huska JA, & Keane TM (1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility. Paper presented at the Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, Tx. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, & Norman SB (2011). Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depress Anxiety, 28(7), 596–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]