Abstract

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) has a strong racial and ethnic component and disproportionately affects whites of European background. Recent incidence reports suggest an increasing rate of MS among African Americans compared with whites. Despite this recent increase in MS in African Americans, Hispanics and Asians are significantly less likely to develop MS than whites of European ancestry. MS-specific mortality trends demonstrate distinctive disparities by race/ethnicity and age, suggesting that there is an unequal burden of disease. Inequalities in health along with differences in clinical characteristics that may be genetic, environmental, and social in origin may be contributing to disease variability and be suggestive of endophenotypes. The overarching goal of this review was to summarize the current understanding on the variability of disease that we observe in selected racial and ethnic populations: Hispanics and African Americans. Future challenges will be to unravel the genetic, environmental and social determinants of the observed racial/ethnic disparities.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, race, ethnicity, health disparity, genetic ancestry

Introduction:

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a genetically complex autoimmune disease with an incidence and prevalence that is reported to differ with race and ethnicity.(1) World distribution supports that northern latitudes have the highest prevalence of MS(2) and that its considerably lower in Asian and Hispanic populations. However, the incidence of MS for African Americans is increasing(3, 4) which could suggest both environmental and genetic changes. On the other hand, Hispanics are increasingly reported among pediatric MS cohorts(5) with an overall younger age of onset noted among Hispanic adult cohorts.(6, 7) The variability in clinical presentation and disease severity reported for both groups could suggest an MS endophenotype that could be used to identify high-risk individuals. In this review, we summarize current observations and trends that highlight ramifications that stem from the complexity of race and ethnicity as a composite variable in disease presentation, severity and progression. Focusing on African Americans and Hispanics we hope to present a framework to further explore the concept of race and ethnicity in MS and its related health disparities.

Definitions behind Race and Ethnicity

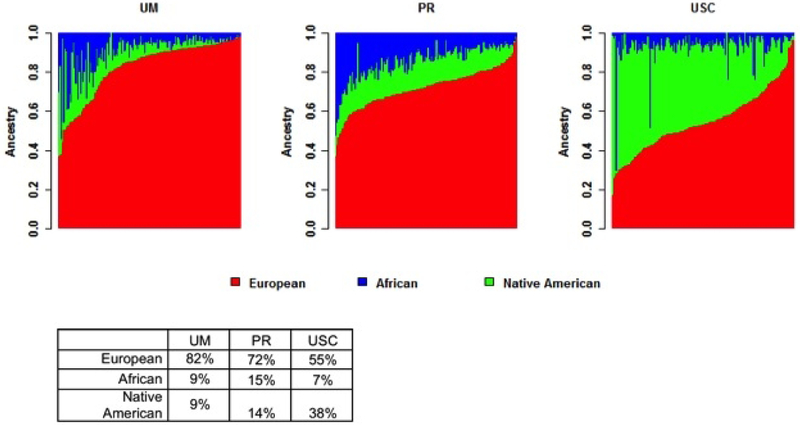

Race and ethnicity are widely used interchangeably in population research. However, more often it is used as a simple demographic variable where the methods to arrive at categorization are seldom discussed. The use of self-identification combined with physical characteristics and medical records could provide a better framework when examining race and ethnicity in disease. Race presumes a person’s physical appearance (i.e. skin color) and biological differences that may concern phenotype or genotype in disease. Ethnicity tries to infer societal differences related to cultural heritage, language and other social and geopolitical factors.(8) While informative and helpful in clustering individuals with common features and background, they do not reveal the extent of genetic admixture in an individual’s ancestry. This is particularly important to consider in a disease such as MS where both genetics and race play a role. The genetic admixture of both African Americans and Hispanics across the United States (US) differ in the proportion of European and African genetic background as well as Native American proportions between Hispanic ethnicities.(9) These admixture differences are the result of geopolitical changes and migrations that occurred between continentally divided ancestral populations within the past 200–500 years leading to genetic variant frequency differences among these various groups.(9) For example the use of a single Hispanic ethnic category is insufficient to distinguish genetic variability between Mexican and Puerto Rican populations, which could be important when examining why a certain disease that has a genetic basis is more common among individuals with Puerto Rican ancestry versus those individuals of Mexican ancestry. On average, our own work in Hispanics with MS further highlights the genetic ancestral differences between Hispanic groups; Mexican-Americans have a higher proportion of Native American ancestry (~38%) but lower African ancestry (average 7%) than Puerto Ricans who have on average 15% or higher African ancestry (Figure 1).(10, 11)

Figure 1:

The distribution of global ancestry proportions for self-identified Hispanic MS cases by ascertainment site within Alliance for Research in Hispanic MS (ARHMS). Predominantly Caribbean Hispanic patients ascertained at both the University of Miami (UM; n=150) and within Puerto Rico (PR; n=150) versus largely Mexican-American ascertainment at the University of Southern California (USC; n=150).

Summary:

Race and ethnicity, combined, is a multidimensional construct that reflects exposure to external health risks posed by environmental, genetic, social, and behavioral factors. Examining the ancestral heterogeneity in Hispanics and African Americans, could help detect genetic variation which can be used as a tool to sort biological from non-biological explanations of MS.(9)

Methodologies in Determining Race/Ethnicity

Changing demographics in MS are suggested by large multiethnic datasets in the US. Electronic medical records (EMR) have been successfully used to improve patient care and obtain important information on demographic and clinical characteristics. Not neglecting their importance to our understanding of MS, the reliance on race and ethnic categorization using EMR and death certificates can sometimes be problematic and lead to an underestimation of certain ethnic minority groups.(12, 13) Lower sensitivity and positive predictive values have been reported when comparing ethnicity of Hispanics (0.55 and 0.81, respectively) and Native Americans (0.47 and 0.50; respectively) from hospital admissions records compared to self-reported study interviews.(14) Misclassification of race and ethnicity has also been reported when comparing EMR to birth certificates with the lowest percent correlations being reported for Asian, Native American, and those that report as multiple ethnic/racial background (~18–74%).(13) A separate study reported that the classification of race and ethnicity on death certificates between 1999–2011 were not significantly problematic for Hispanics.(15) However, misclassification remained high at 40% for Native American related ancestry. Thus, Asian, Native American, and Hispanic groups are more likely to be underestimated.

MS Prevalence/Incidence and Race/Ethnicity

In the last several years, changes in the demographics of MS have been reported around the world.(3, 16, 17) In the US, both African Americans and Hispanics are being increasingly diagnosed and recent studies reflect changes that contradict the once held belief that African Americans were a low MS risk population. A retrospective cohort study using electronic medical records from the Kaiser Permanente plan in Southern California reported African Americans to have a 47% increased risk of MS, while Hispanic Americans had a 50% lower risk and Asian Americans had an 80% lower risk of MS compared with white Americans (2.9 per 100,000 for Hispanics vs. 6.9 for whites).(3) Wallin and colleagues, using data from the US military Veteran population, also reported similar observations indicating higher rates of MS in African Americans.(4) Lower risk of MS in both studies was consistently reported for Hispanics and Asians. Interestingly, a Canadian study reported the incidence of MS to be increasing among females of Asian background living in British Colombia where the incidence doubled during the period of 1986–2010 while the non-Asian white population remained unchanged.(17) The explanation for these changing demographics are unknown but certainly could reflect environmental and social factors but less so genetic susceptibility as changes would be too rapid to be explained by genetic alterations.

Mortality and Race/Ethnicity

MS-specific mortality trends also demonstrate distinctive disparities by race/ethnicity and age, suggesting that there is an unequal burden of disease.(18) While limited, mortality rates in the US have been reported to be the highest in whites followed by blacks with Asians and Hispanics having the lowest rates.(19) Using the compressed mortality data file for 1999–2015 in the wide-ranging online data for the Epidemiological Research System developed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in the US, we calculated the age-adjusted and age-specific MS mortality rate by sex and five distinct ethnic groups: Hispanic, non-Hispanic (NH) black, NH white, NH Asian Pacific islander and NH American Indian and Alaska Native.(18) While an increasing trend in age-adjusted MS mortality was observed during 1999–2015 among NH whites and NH blacks, age-specific MS mortality patterns highlighted NH black males as the greatest group at risk particularly before age 45. This US based study suggests that the burden of disease weighs differently by race and ethnicity, which has also been previously suggested by studies using the North American Research Committee for MS registry, which includes both US and Canadian enrollees.(20) Disparities in mortality rates between racial and ethnic groups should raise questions about particular characteristics in these groups, including the co-existence of comorbidities and/or alternate diagnoses that can mimic MS, have a higher prevalence, and are associated with higher morbidity and mortality (e.g. neuromyelitis optica (NMO) spectrum disorders(21, 22)) in African and Hispanic backgrounds.

Race and ethnic clinical variability in MS:

Multiple observational studies suggest that African Americans and Hispanics have unique clinical characteristics that could be the result of genetic and environmental factors.(23) These reports reflect less than 1% of the published literature in MS(24) but nevertheless suggest that variations in MS clinical, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), disease severity and progression are the result of complex interactions between genetic predispositions and environmental factors that could be reflective of endophenotypes.(25)

Race and Ethnicity and Age of Onset of MS:

African Americans have been reported to develop MS both at an earlier(26) and at a later(27) age compared with whites. These discrepancies in age of onset have not been rectified, but interestingly the studies appear to differ by region of ascertainment such that the earlier age observation came from the east coast and the older age reflected a west coast African-American population. Hispanics are also reported to present with MS at a younger age compared with whites(3, 6, 7, 26) and African Americans.(3, 26) Self-identified US Hispanics are found to develop MS 3–5 years younger compared to non-Hispanic whites and this younger age of onset is further seen for those Hispanics born in the US compared to those that are foreign born. Age of onset was also significantly younger (p > 0.001) for those who were US born compared to immigrant Hispanics form Latin America to the US at adolescent age or older with 74% developing MS in the US on average 15 years later from age of immigration.(7, 28) This observation continues to be consistent across other regions of the US(6) and other countries where migration has occurred between lower to higher latitudes.(29) These data favor the influence of environmental risk factors to be age dependent and suggests that birth and residence at higher geographic latitudes are also factors important in the development of MS in Hispanics.

Environmental risk factors for MS associated with Race and Ethnicity

Recent multiethnic investigations into the cause of MS have reported that known environmental risk factors in white non-Hispanic populations may not be as relevant in African Americans and Hispanics.(30–32) Epstein-Barr virus has been consistently associated with the risk of MS and recent studies also support that being Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1 seropositive is associated with an increase odds of getting MS across diverse ethnic backgrounds: African Americans, Hispanics and whites. However, CMV seropositivity was only found to be associated with a lower risk of MS in Hispanics (p = 0.004) and having been born in a low income country appeared to contribute to being seropositive. These differential observations behind CMV could suggest that timing of exposure is due to social and behavioral differences not only between cases and controls but also by race and ethnicity. Evaluating vitamin D as a risk factor in the same multiethnic cohort and the development of MS however further confirmed that having higher serum levels of 25OHD is associated with a lower risk of MS in whites, but no association was found in Hispanics or blacks. Nevertheless, a higher lifetime ultraviolet radiation exposure appeared to be statistically significant in lowering the risk of MS in blacks and whites but not in Hispanics. A follow-up study involving the same population evaluated whether these negative results in blacks and Hispanics could be best explained by differential polymorphisms in the vitamin D-binding protein gene. Interestingly, dominant polymorphisms in the vitamin D-binding protein gene were not helpful in explaining the lack of association between 25OHD and MS in blacks and Hispanics. These studies challenge the notion that MS risk factors are equal across populations but underscore the greater effect of race and ethnicity on MS.

Genetic Risk Factors for MS associated with Race and Ethnicity

Genetic factors have also been reported to influence age of onset using minority cohorts. A study of African Americans with MS reported that African Ancestry at the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)(33) influences clinical outcomes in this population. African Americans with MS who were carriers of the (HLA)DRB1*15 allele were twice more likely to have an earlier age of onset and had a 2.1-year younger mean age at disease onset compared to those not carrying DRB1*15 alleles. (33) Additionally, genetic variants from non-HLA risk genes reported in white MS cohorts have been tested in an African American cohort noting a trend of an effect on earlier age of onset in those individuals carrying the risk variant within the RGS1 gene locus.(34) Suggestions of potential genetic factors related to Hispanic ancestry influencing age of onset are also evident by our recently published study in self-identified Hispanics.(11) As part of our research efforts within the Alliance for Research in Hispanic MS (ARHMS) consortium, we evaluated the association of global genetic ancestry with age at first symptom in a large (n=1033) well-characterized multi-center cohort. Using multivariate linear regression we observed a significant association between genetic ancestry and age of first symptom (P=6.37×10−04; joint test of Native American and African ancestry). Both an increase in African (beta=−10.07, P=1.39×10−03) and Native American (beta= −5.58, P=3.49 × 10−02) ancestry contributed to a younger age at first symptom.(11)

Summary:

Geographical location before onset of multiple sclerosis remains a risk factor in MS and studies of both African and Native American genetic ancestry demonstrate an increased risk for younger age of onset. While our data lend support to this hypothesis, we recognize the need for more complete environmental studies that integrate genetic ancestry and migration details. These observations underscore that an earlier age of onset is an expected feature of minority MS and may confer prognostic value.

Race and Ethnicity and Disease Severity and Progression:

There are racial and ethnic effects that suggest both African American and Hispanics when compared to whites to be high-risk populations for early disability and worse prognosis.(1) Using the Patient-Derived Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score (P-MSSS) significantly higher disability scores have been reported for both Hispanics (3.9 ± 2.6) and African Americans (4.5 ± 3.0) compared to whites (3.4 ± 2.6; p < 0.0001; adjusted for age).(26) Additional measures supporting greater disability in African Americans stem from optical coherence tomography (OCT) studies and MRI where recently greater accelerated retinal damage over time(35, 36) and brain tissue loss, including regional brain atrophy(35) changes, have been reported compared to whites. While imaging measures concerning Hispanics are nearly scarce, disability measures have been reported to differ by age of immigration to the US and place of birth. Foreign born and older age of immigration to the US were found to be independently associated with increased ambulatory disability (adjusted OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.07–4.82; p = 0.03).(28)

Summary:

The mechanisms accounting for these differences in disability measures between whites and minority populations with MS here in the US are still poorly understood. The potential for confounders such as environmental and social factors makes it hard to generalize that MS is more aggressive in minorities. Nevertheless, studies in immigrants to the US that develop MS years later and coming from lower prevalence regions offer a unique opportunity to explore the effects of environmental and diet changes. Obtaining data related to changes that accompany migration may facilitate an opportunity to evaluate known risk factors as well as identify potential new triggers or modifiers. However, barriers to obtaining these types of data will include the geopolitical environment pertinent to new immigrants to the US.

Disparities in Health Outcomes

African Americans and Hispanics make-up nearly 30% of the US population and are geographically unequally distributed throughout the country (web 1). Being a minority in the US has strong links to health disparities due to social disadvantages. Disadvantages are characterized by such factors as living in poverty, being poorly educated, and other socioeconomic factors. Health disparities are defined as avoidable differences in health status, mortality and burden of disease that disproportionately affects some groups despite having similar characteristic such as gender.(37, 38) While health inequity and health disparity are intertwined, health inequities are health disparities in the access to or availability of health-related facilities and services.(38) Thus, social, economic, and environmental circumstances in which these minority groups are born to and are living in could account for some of the clinical variations in disease severity. There is evidence supporting health literacy problems when it comes to MS related disease modifying treatments and their realistic expectations,(39) poor access to specialty care, and illness perceptions affecting self-care.(40, 41) Analysis of individuals with MS using the Independence Care System, a Medicaid long-term managed care plan in New York, found several deficiencies in the care of low-income minorities with MS where 30% had never seen an MS specialist and another 30% were not taking disease modifying treatments due to poor compliance and understanding of the drug.(39) Similar access problems were recently reported using a nationally representative dataset from the 2006–2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey where both blacks and Hispanics with MS were less likely to see a neurologist compared to whites (30% and 40% less, respectively).(40)

Summary:

Proper care access, health literacy, and illness perceptions affect adults in all racial and ethnic groups, with a greater proportion reported in US minorities. Future studies that incorporate factors related to healthcare system, provider-patient relationships, and the patient’s and community needs, beliefs and expectations,(42) would support a more inclusive way of studying outcomes in MS.

Future Directions:

Understanding the effect of race/ethnicity is crucial in understanding MS disparities. Whether there are racial and ethnic group characteristics that would relate to an endophenotype is still unclear. Studying the impact of genetic and environmental variation, and ancestry and its relationship to health disparities on MS across populations will help ensure that precision medicine efforts will be impactful to all groups. Minorities with MS face greater barriers related to access and education in MS care. Additionally, clinical trials have <10% clinical trial participation from minorities(43) which should call into question efficacy profiles of disease modifying treatments. This lack of representation is not well understood but may reflect minorities having less access to specialists who are more likely to be at specialty care centers that recruit subjects for clinical trials. The fear of exploitation, due to a not too distant past history of unethical medical testing in the US (i.e. Tuskegee experiments and others) and lack of time or financial resources to participate and other competing barriers add another layer of complexity when examining race and ethnicity in MS.(24) Collaborative research networks that strive to develop trust and teamwork with the community, such as the Alliance for Research in Hispanics MS(44) (Web 2) and the Minority Research Engagement Partnership, could help further these research efforts.

Acknowledgements:

The authors like to thank Dr. Brett Lund, Andrea Martinez and Patricia Manrique to their contributions to data collection in support of ARHMS. We also acknowledge the Center for Genome Technology within the University of Miami John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics for generating the genotype data for this project and the funding sources to support it: National Institute of Health (NINDS 1R01NS096212‐01 award to J. McCauley (primary), L. Amezcua and NMSS RG-1607–25324 award to L. Amezcua (primary), J. McCauley.

References:

Web 1: Unites States Census Bureau Quick Facts https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120217 Accessed June 9, 2019

Web 2: Alliance for research in Hispanic MS https://www.arhms.org/ Accessed June 9, 2019

- 1.Rivas-Rodriguez E, Amezcua L. Ethnic Considerations and Multiple Sclerosis Disease Variability in the United States. Neurologic clinics. 2018. February;36(1):151–62. Epub 2017/11/22. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborators GBDMS. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology. 2019. March;18(3):269–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langer-Gould A, Brara SM, Beaber BE, Zhang JL. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in multiple racial and ethnic groups. Neurology. 2013. May 7;80(19):1734–9. Epub 2013/05/08. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Coffman P, Pulaski S, Maloni H, Mahan CM, et al. The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2012. June;135(Pt 6):1778–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belman AL, Krupp LB, Olsen CS, Rose JW, Aaen G, Benson L, et al. Characteristics of Children and Adolescents With Multiple Sclerosis. Pediatrics. 2016. July;138(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadjixenofontos A, Beecham AH, Manrique CP, Pericak-Vance MA, Tornes L, Ortega M, et al. Clinical Expression of Multiple Sclerosis in Hispanic Whites of Primarily Caribbean Ancestry. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44(4):262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amezcua L, Lund BT, Weiner LP, Islam T. Multiple sclerosis in Hispanics: a study of clinical disease expression. Multiple sclerosis. 2011. August;17(8):1010–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankar P, Cho MK. Genetics. Toward a new vocabulary of human genetic variation. Science. 2002. November 15;298(5597):1337–8. Epub 2002/11/16. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mersha TB, Abebe T. Self-reported race/ethnicity in the age of genomic research: its potential impact on understanding health disparities. Human genomics. 2015. January 7;9:1 Epub 2015/01/08. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galanter JM, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Gignoux CR, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Fernandez-Rozadilla C, Via M, et al. Development of a panel of genome-wide ancestry informative markers to study admixture throughout the Americas. PLoS genetics. 2012;8(3):e1002554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amezcua L, Beecham AH, Delgado SR, Chinea A, Burnett M, Manrique CP, et al. Native ancestry is associated with optic neuritis and age of onset in hispanics with multiple sclerosis. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2018. November;5(11):1362–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coker TR, Elliott MN, Kataoka S, Schwebel DC, Mrug S, Grunbaum JA, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in the mental health care utilization of fifth grade children. Academic pediatrics. 2009. Mar-Apr;9(2):89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith N, Iyer RL, Langer-Gould A, Getahun DT, Strickland D, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Health plan administrative records versus birth certificate records: quality of race and ethnicity information in children. BMC health services research. 2010. November 23;10:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez SL, Kelsey JL, Glaser SL, Lee MM, Sidney S. Inconsistencies between self-reported ethnicity and ethnicity recorded in a health maintenance organization. Annals of epidemiology. 2005. January;15(1):71–9. Epub 2004/12/02. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arias E, Heron M, Hakes J. The Validity of Race and Hispanic-origin Reporting on Death Certificates in the United States: An Update. Vital and health statistics Series 2, Data evaluation and methods research. 2016. August 1(172):1–21. Epub 2017/04/25. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinea A, Rios-Bedoya CF, Vicente I, Rubi C, Garcia G, Rivera A, et al. Increasing Incidence and Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Puerto Rico (2013–2016). Neuroepidemiology. 2017;49(3–4):106–12. Epub 2017/11/15. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JD, Guimond C, Yee IM, Vilarino-Guell C, Wu ZY, Traboulsee AL, et al. Incidence of Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders in Asian Populations of British Columbia. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 2015. July;42(4):235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amezcua L, Rivas E, Joseph S, Zhang J, Liu L. Multiple Sclerosis Mortality by Race/Ethnicity, Age, Sex, and Time Period in the United States, 1999–2015. Neuroepidemiology. 2018;50(1–2):35–40. Epub 2018/01/18. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redelings MD, McCoy L, Sorvillo F. Multiple sclerosis mortality and patterns of comorbidity in the United States from 1990 to 2001. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26(2):102–7. Epub 2005/12/24. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capkun G, Dahlke F, Lahoz R, Nordstrom B, Tilson HH, Cutter G, et al. Mortality and comorbidities in patients with multiple sclerosis compared with a population without multiple sclerosis: An observational study using the US Department of Defense administrative claims database. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders. 2015. November;4(6):546–54. Epub 2015/11/23. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flanagan EP, Cabre P, Weinshenker BG, Sauver JS, Jacobson DJ, Majed M, et al. Epidemiology of aquaporin-4 autoimmunity and neuromyelitis optica spectrum. Annals of neurology. 2016. May;79(5):775–83. Epub 2016/02/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarenga MP, Schimidt S, Alvarenga RP. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica in Latin America. Multiple sclerosis journal-experimental, translational and clinical. 2017. Jul-Sep;3(3):2055217317730098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivas-Rodriguez E, Amezcua L. Ethnic Considerations and Multiple Sclerosis Disease Variability in the United States. Neurologic clinics. 2018;36(1):151–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan O, Williams MJ, Amezcua L, Javed A, Larsen KE, Smrtka JM. Multiple sclerosis in US minority populations: Clinical practice insights. Neurology Clinical practice. 2015. April;5(2):132–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramagopalan SV, Dobson R, Meier UC, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis: risk factors, prodromes, and potential causal pathways. The Lancet Neurology. 2010. July;9(7):727–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ventura RE, Antezana AO, Bacon T, Kister I. Hispanic Americans and African Americans with multiple sclerosis have more severe disease course than Caucasian Americans. Multiple sclerosis. 2017. October;23(11):1554–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cree BA, Khan O, Bourdette D, Goodin DS, Cohen JA, Marrie RA, et al. Clinical characteristics of African Americans vs Caucasian Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004. December 14;63(11):2039–45. Epub 2004/12/15. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amezcua L, Conti DV, Liu L, Ledezma K, Langer-Goulda AM. Place of birth,age of immigration,and disability in Hispanics with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015. January;4(1):25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elian M, Nightingale S, Dean G. Multiple sclerosis among United Kingdom-born children of immigrants from the Indian subcontinent, Africa and the West Indies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990. October;53(10):906–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langer-Gould A, Lucas R, Xiang AH, Chen LH, Wu J, Gonzalez E, et al. MS Sunshine Study: Sun Exposure But Not Vitamin D Is Associated with Multiple Sclerosis Risk in Blacks and Hispanics. Nutrients. 2018. February 27;10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer-Gould A, Lucas RM, Xiang AH, Wu J, Chen LH, Gonzales E, et al. Vitamin D-Binding Protein Polymorphisms, 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, Sunshine and Multiple Sclerosis. Nutrients. 2018. February 7;10(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langer-Gould A, Wu J, Lucas R, Smith J, Gonzales E, Amezcua L, et al. Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and multiple sclerosis susceptibility: A multiethnic study. Neurology. 2017. September 26;89(13):1330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cree BA, Reich DE, Khan O, De Jager PL, Nakashima I, Takahashi T, et al. Modification of Multiple Sclerosis Phenotypes by African Ancestry at HLA. Archives of neurology. 2009. February;66(2):226–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson BA, Wang J, Taylor EM, Caillier SJ, Herbert J, Khan OA, et al. Multiple sclerosis susceptibility alleles in African Americans. Genes and immunity. 2010. June;11(4):343–50. Epub 2009/10/30. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caldito NG, Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Dewey BE, Cowley NJ, Glaister J, et al. Brain and retinal atrophy in African-Americans versus Caucasian-Americans with multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2018. November 1;141(11):3115–29. Epub 2018/10/13. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimbrough DJ, Sotirchos ES, Wilson JA, Al-Louzi O, Conger A, Conger D, et al. Retinal damage and vision loss in African American multiple sclerosis patients. Annals of neurology. 2015. February;77(2):228–36. Epub 2014/11/11. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014. Jan-Feb;129 Suppl 2:5–8. Epub 2014/01/05. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abbott LS, Elliott LT. Eliminating Health Disparities through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: A Systematic Review of Home Visiting in the United States, 2005–2015. Public Health Nurs. 2017. January;34(1):2–30. Epub 2016/05/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shabas D, Heffner M. Multiple sclerosis management for low-income minorities. Mult Scler. 2005. December;11(6):635–40. Epub 2005/12/03. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saadi A, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Mejia NI. Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology. 2017. June 13;88(24):2268–75. Epub 2017/05/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obiwuru O, Joseph S, Liu L, Palomeque A, Tarlow L, Langer-Gould AM, et al. Perceptions of Multiple Sclerosis in Hispanic Americans: Need for Targeted Messaging. International journal of MS care. 2017. May-Jun;19(3):131–9. investigator-initiated grant support from Acorda, Biogen, Genzyme, and Novartis. Dr. Langer-Gould has received research funding from Biogen Idec, Hoffmann-La Roche, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canino G, McQuaid EL, Rand CS. Addressing asthma health disparities: a multilevel challenge. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2009. June;123(6):1209–17; quiz 18–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Avasarala J. Inadequacy of clinical trial designs and data to control for the confounding impact of race/ethnicity in response to treatment in multiple sclerosis. JAMA neurology. 2014. August;71(8):943–4. Epub 2014/06/10. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amezcua L, Oksenberg JR, McCauley JL. MS in self-identified Hispanic/Latino individuals living in the US. Multiple sclerosis journal-experimental, translational and clinical. 2017. Jul-Sep;3(3):2055217317725103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]