Abstract

Background:

Overactivation of ryanodine receptors and the resulting impaired calcium homeostasis contribute to Alzheimer’s disease-related pathophysiology. We hypothesized that exposing neuronal progenitors derived from induced pluripotent stems cells of patients with Alzheimer’s disease to dantrolene will increase survival, proliferation, neurogenesis and synaptogenesis.

Methods:

Induced pluripotent stem cells, obtained from skin fibroblast of healthy subjects, patients with familiar and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, were used. Biochemical and immunohistochemical methods were applied to determine the effects of dantrolene on viability, proliferation, differentiation and calcium dynamics of these cells.

Results:

Dantrolene promoted cell viability and proliferation in these two cell lines. Compared to the control, differentiation into basal forebrain cholinergic neurons significantly decreased by 10.7% (32.9 ±3.6% vs. 22.2 ±2.6%, N=5, P=0.004) and 9.2% (32.9 ±3.6% vs. 23.7 ±3.1%, N=5, P=0.017) in cell lines from sporadic and familiar Alzheimer’s patients, respectively, which were abolished by dantrolene. Synapse density was significantly decreased in cortical neurons generated from stem cells of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease by 58.2% (237.0± 28.4 vs. 99.0 ± 16.6 arbitrary units N=4, P=0.001) or familiar Alzheimer’s disease by 52.3% (237.0± 28.4 vs.113.0 ± 34.9 vs arbitrary units, N=5, P=0.001), which was inhibited by dantrolene in familiar cell line. Compared to the control, ATP (30 μM) significantly increased higher peak elevation of cytosolic calcium concentrations in cell line from sporadic Alzheimer’s patients (84.1± 27.0% vs. 140.4 ± 40.2%, N=5, P=0.049), which was abolished by the pretreatment of dantrolene. Dantrolene inhibited the decrease of lysosomal vATPase and the impairment of autophagy activity in these two cell lines from Alzheimer’s disease patients.

Conclusions:

Dantrolene ameliorated the impairment of neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, in association with restoring intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and physiological autophagy, cell survival and proliferation in induced pluripotent stem cells and their derived neurons from sporadic and familiar Alzheimer’s disease patients.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Calcium, Neurogenesis, autophagy, neurodegeneration

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating neurodegenerative disease.1 The deficit in the development of new drugs targeting the amyloid pathology over the past several decades2 warrants exploration of alternative pathways that could be the primary cause of Alzheimer’s disease cognitive dysfunction. Ca2+ dysregulation via overactivation of the endoplasmic reticulum ryanodine receptor is thought to play a central, upstream role in the neuropathology and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease.3–7 Some familial Alzheimer’s disease gene mutations cause ryanodine receptor overexpression, resulting in excessive endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release via activated ryanodine receptor, 8,9 which in turn worsen amyloid and Tau pathology, neurodegeneration and synapse dysfunction. Moreover, adult neurogenesis, critical for maintaining synaptic and cognitive function during aging is also impaired10,11. Considering the important role of Ca2+ in the regulation of neurogenesis12, it is important to understand the mechanisms of impairment of neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease.

Sporadic Alzheimer’s disease accounts for more than 95% of Alzheimer’s disease patients, but its pathology is largely unknown. Lack of understanding of the mechanisms and inadequate cell or animal models of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease limit the development of new effective drugs for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Although the pathology and mechanisms of familial Alzheimer’s disease have been relatively well studied, they are primarily in cell and animal models, not in patients. Recent advancement in the development of induced pluripotent stem cells from skin fibroblasts of Alzheimer’s disease patients allows for a new cell model to study pathology in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and test the therapeutic efficacy of new drugs, especially for the process of neurogenesis.13

Dantrolene, which reduced mortality of malignant hyperthermia from 85% to below 5%14, is the only US Food and Drug Administration approved clinically available drug to treat malignant hyperthermia. Chronic use of oral dantrolene is also utilized to treat muscle spasm, with relatively tolerable side effects.15 Although not fully consistent3, the majority of recent studies,5,6,16,17 indicate that chronic use of dantrolene significantly ameliorated memory loss and amyloid pathology in various familial Alzheimer’s disease animal models, with acceptable adverse reactions. The mechanisms of dantrolene neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease were also investigated in vitro, including the correction of Ca2+ disruption, inhibition of neurodegeneration and synapse dysfunction etc.15,18 However, significant gaps of knowledge need to be filled before dantrolene can be studied as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease patients: 1). Mechanisms by which dantrolene ameliorates cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease; 2). Efficacy of dantrolene neuroprotection in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells or animal model, especially in tissues from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients; 3). Effects of dantrolene on neurogenesis in human sporadic Alzheimer’s disease models. We hypothesized that dantrolene inhibit impaired neurogenesis and synaptogenesis by correction of Ca2+ dysregulation due to overactivation of ryanodine receptor and associated impairment of lysosome and autophagy function. In this study and with the use of induced pluripotent stem cells from both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease patients and their derived neuroprogenitor cells and basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, we studied the effects and mechanisms of dantrolene on neurogenesis and synaptogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human control (AG02261) and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (AG11414) induced pluripotent stem cells were obtained from John A. Kessler’s lab.19 Familial Alzheimer’s disease (GM24675) induced pluripotent stem cells was purchased from Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ, USA). Each type of induced pluripotent stem cells was generated from skin fibroblasts of one heathy human subject or one patient diagnosed of either sporadic Alzheimer’s disease or familial Alzheimer’s disease. AG02261 cell line was derived from a 61-year-old male healthy patient. Another AG11414 cell line came from a 39-year-old male patient with early onset Alzheimer’s disease who displayed an APOE3/E4 genotype. GM24675 cell line was derived from a 60-year-old familial Alzheimer’s disease patient with APOE genotype 3/320. The human pluripotent stem cells were maintained on Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) coated plates in mTeSR™1 medium (Catalog #05850, Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and were cultured in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. The culture medium was changed every day. We routinely checked the cells before the experiments for healthiness and those unhealthy cells (e.g. nonadherent cells) were removed. We randomly assign the cells into two experimental groups. During the experiments, if the cultured cells were visibly infected, the data were removed and not used. This happened 2 times in cell viability experiments.

Cell viability

The cell viability on different wells in 96-well plates was determined using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) reduction assay at 24 h as we previously described.21,22 After being washed with phosphate buffered saline, the samples were incubated with fresh culture medium containing MTT (0.5 mg/ml in the medium) at 37 °C for 4 h in the dark. The medium was then removed, and formazan was solubilized with dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance was measured at 540 nm with plate reader (Synergy™ H1 microplate reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Cell Proliferation Assays

The induced pluripotent stem cells were plated onto cover glasses coated with Matrigel in mTeSR™1 medium. 5-Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) was added to the mTeSR™1 medium 4h before the end of treatment with a final concentration of 30μM. The cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. For BrdU detection, acid treatment (1N HCL 10 min on ice followed by 2N HCL 10 min at room temperature) separated DNA into single strands so that the primary antibody could access the incorporated BrdU. After being incubated with blocking solution (5% normal goat serum in phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100), cells were incubated with rat monoclonal anti-BrdU primary antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) overnight at 4°C. After subsequent wash with phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100, cells were incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody conjugated with anti-rat IgG (1: 1,000; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) for 2h at room temperature. Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) for 5 min at room temperature. The immunostained cells were covered and then mounted on an Olympus BX41TF fluorescence microscope (200×; Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA, USA). Images were acquired using iVision 10.10.5 software (Biovision Technologies, Exton, PA, USA). Five sets of images were acquired at random locations on the cover glass and were subsequently merged using Image J 1.49v software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The percentage of 5-BrdU-positive cells over the total number of cells was calculated and compared across different groups from at least three different cultures.

Differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells

The protocol for differentiation into cortical neurons and basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from induced pluripotent stem cells was adapted from previously described protocol23,24. Briefly, feeder-free culture was induced to neural progenitors via Dual-SMAD inhibition. The cells were cultured in chemical defined condition with SB431542 2uM and DMH1 2uM (both from Tocris, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 7 days.

For cortical neurons, change the medium to neural maintenance medium (This is a 1:1 mixture of N-2 and B-27-containing media. N-2 medium consists of DMEM/F-12 GlutaMAX, 1×N-2, 5μg ml−1 insulin, 1mM L-glutamine, 100μm nonessential amino acids, 100μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50Uml−1 penicillin and 50 mg ml−1 streptomycin. B-27 medium consists of Neurobasal, 1×B-27, 200mM L-glutamine, 50 U ml−1penicillins and 50 mg ml−1 streptomycin.) from day 12. Neural rosette structures should be obvious when cultures are viewed with an inverted microscope around day 12–17. From this point, medium was changed every other day.

For basal forebrain cholinergic neurons differentiation, the induced pluripotent stem cells-derived primitive neural stem cells were developed under Recombinant Human Sonic Hedgehog (500 ng/ml (1845-SH) and then treated with nerve growth factor (1156-NG-100, 50–100 ng/ml; both from R&D Systems, MN, USA) from day 24. At day 28 the neural progenitors were plated on the poly-L-ornithon/laminin coated plates at a density of 5,000 cells/cm2, then cultured in neuronal differentiation medium consisting of neurobasal medium, N2 supplement ( Invitrogen) in the presence of Nerve growth factor (50–100 ng/ml), cAMP (1 μM; Sigma), BDNF, GDNF (10 ng/ml; R&D), Recombinant Human Sonic Hedgehog (50 ng/ml; R&D).25

Ca2+ measurements

The changes of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) of induced pluripotent stem cells after ATP exposure were measured using jellyfish photoprotein aequorin-based probe, 7.5 −12 × 104 cells were plated on 12 mm coverslips in 24 well plate, grow to 50–60% confluence then transfected with the cyt-Aeq plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The next day, the transfected cells were incubated with 5 μM coelenterazine for 1 h in modified Krebs–Ringer buffer (in mM: 140 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 11 glucoses, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2 and then were transferred to the perfusion chamber. All aequorin measurements were carried out in KRB, anesthetics were added to the same medium as specified in the text. The experiments were performed in a custom-built aequorin recording system. For extracellular Ca2+ free experiment, Ca2+ free buffer was used (KRB without Ca2+ with 5mM EGTA). The experiments were terminated by lysing the cells with 100 μM digitonin in a hypotonic Ca2+-rich solution (10 mM CaCl2 in H2O), thus discharging the remaining aequorin pool. The light signal was collected and calibrated into [Ca2+]c values by an algorithm based on the Ca2+ response curve of aequorin at physiological conditions of pH, [Mg2+], and ionic strength, as previously described26,27.

The changes of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) of induced pluripotent stem cells after exposure to NMDA was measured by Fura-2/AM fluorescence (Molecular probe, Eugene, OR) using methods described before. Assays were carried out on an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope (Olympus America Inc, Center Valley, PA, USA) and IPLab v3.71 software (Scanalytics, Milwaukee WI, USA). In brief, the induced pluripotent stem cells were plated onto a 35mm culture dish. After the cells were washed three times in Ca2+-free Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and loaded with 2.5 μm Fura-2/AM in the same buffer for 30 min at 37 °C, the cells were then washed twice and incubated with Ca2+-free DMEM for another 30 min at 37 °C. Fura-2AM was measured by recording alternate at 340 and 380 nm excitation, and emission at 510 nm was detected for up to 10 min for each treatment. The evoked changes were recorded in response to treatment of 500μM NMDA with or without dantrolene 30 μM (Dan). The results were presented as a ratio of F340/F380 nm and averaged from at least three separate experiments.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed according to the standard procedure. Total protein extracts from induced pluripotent stem cells were obtained by lysing the cells in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100) in the presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitors28. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected, and the total protein was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein for each lane were loaded and separated on 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk dissolved in phosphate buffered saline-T for 1 h at room temperature, and then stained with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After the wash with phosphate buffered saline-T, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (HRP conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG) at 1: 1,000 dilutions, and β-actin served as a loading control. Signals were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and quantified by scanning densitometry.

Immunocytochemistry

The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes followed by three 1xPBS washes. They were then blocked by 5% normal goat serum in phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 1 hour. Primary antibodies were applied for overnight at 4°C in 1xPBS containing 1% BSA and 0.3% Triton-X-100. Following three washes with phosphate buffered saline, alexa fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000) together with DAPI (1:2000) were added for 1 hour. After three more washes, coverslips were mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Both from Invitrogen) and imaged. Primary antibodies used were listed in the supplemental table 1. Image acquisition and analysis are performed by people blinded to experiment treatment. Five sets of images were acquired at random locations on the cover glass and were subsequently merged using Image J 1.49v software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The percentage of positive cells over the total number of cells was calculated and compared across different groups from at least three different cultures.

Lysosome acidity measurements

As we described before,22 LysoTracker® Red DND-99 (Molecular Probe, Eugene, OR, USA) probe stock solution was diluted to a working concentration of 50 nM in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution. Induced pluripotent stem cells were plated on coverslips coated with Matrigel in mTeSR™1. After being washed three times with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution, the cells were loaded with pre-warmed (37°C) probe containing Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution and incubated for 1h at 37°C. Fresh media was added to replace the labeling solution. The cells were observed by a fluorescent microscope fitted with the correct filter set for the probe used, to determine if the cells were sufficiently fluorescent. LysoTracker Red used an emission maximum of ~590 nm and an excitation maximum of ~577 nm.

Data analysis and statistics

No statistical power calculation was conducted prior to the study. The sample size was based on our previous experience with this design. All data were tested for normal distribution by KS normality test and Brown-Forsythe test to determine if parametric or nonparametric tests are used for statistical analysis. Variables that satisfied the assumptions for parametric analysis were expressed as Means ± SD and analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc analysis. The nature of factors (e.g. repeated measures) and groping of the factors were adequately addressed for ANOVA analysis. Variables that satisfied the assumptions for non-parametric analysis were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA) was used for statistical analyses and graphs creation. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

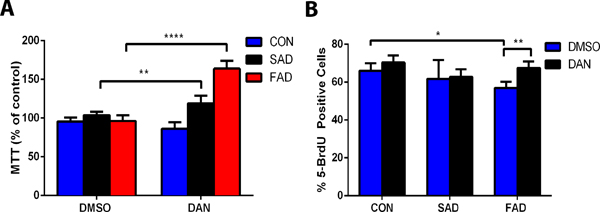

Dantrolene promoted cell viability and inhibited impairment of cell proliferation in induced pluripotent stem cells from Alzheimer’s disease patients

Induced pluripotent stem cells, neuroprogenitor cells and neurons from the healthy human subject or sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients were cultured and characterized by specific antibodies targeting types of cells. There was no significant difference in cell viability determined by MTT reduction assay of induced pluripotent stem cells among healthy human subjects or sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients. However, dantrolene treatment resulted in a significantly greater MTT (percentage of control) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells by 15.1% (103.8± 4.7% vs 118.9 ± 10.3% N=8, P=0.006) and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells by 67.6% (96.4 ± 7.3% vs 163.9 ± 10.1% N=7 replicates P<0.0001, Fig. 1A), than control cells. Compared to healthy human subjects, induced pluripotent stem cells from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients tended to have impaired proliferation ability as determined by 5-BrdU incorporation, more significantly in familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells, which was inhibited by dantrolene (Fig. 1B). Compared to control, dantrolene had no significant effects on induced pluripotent stem cells differentiation into neuroprogenitor cells (Data not shown).

Figure 1. Dantrolene promoted cell viability and inhibited impairment of cell proliferation in induced pluripotent stem cells from Alzheimer’s disease patients.

(A) Treatment of induced pluripotent stem cells with dantrolene (DAN) (30 μM) for 24 h did not affect induced pluripotent stem cells from healthy human subjects (CON) but resulted in a significantly greater cell viability of induced pluripotent stem cells from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD) (p=0.006) and familial Alzheimer disease (FAD) (p<0.0001) patients. For cell viability, interaction, treatment and cell type were all significant sources of variation (F(2,40)=92.56, p<0.0001; F(1,40)=110.40, p<0.0001; F(2,40)=92.81, p<0.0001, respectively). (B) Dantrolene proliferation, measured by the percent BrdU positive cells, was significantly impaired in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells compared to control healthy subjects cells (p=0.022). Compared with vehicle control, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), dantrolene resulted in a greater proliferation in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.008, familial Alzheimer’s disease dantrolene to dimethyl sulfoxide). For proliferation, dantrolene treatment and cell type were significant sources of variation (F(2,30)=5.44, p=0.009; F(1,30)=9.81, p<0.039, respectively). All data are expressed as the mean±SD from 5–8 independent experiments (A, familial Alzheimer’s disease, n=7; control, n=8; sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, n=8), (B, control treated with DMSO n=7, with dantrolene n=5; sporadic Alzheimer’s disease both DMSO and dantrolene group n=5; familial Alzheimer’s disease DMSO n=8, dantrolene n=6). ** P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison tests.

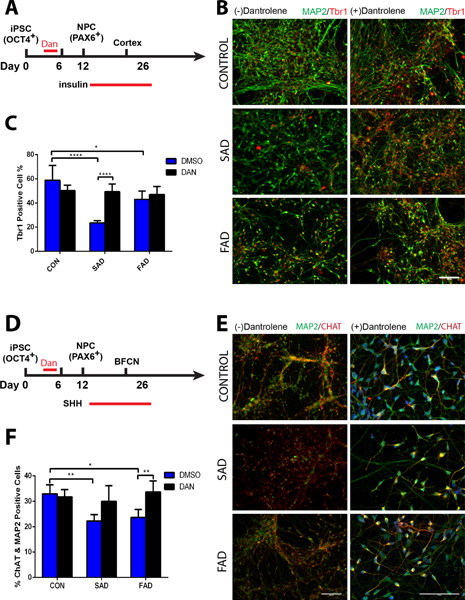

Dantrolene ameliorated the impairment of neuroprogenitor cells differentiation into immature neurons, cortical neurons and basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in both sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells

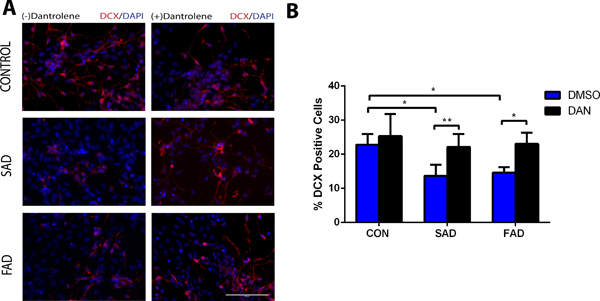

Based on our pilot study to exert adequate dantrolene neuroprotection on neurogenesis, we treated induced pluripotent stem cells with dantrolene (30 μM) for 3 continuous days, beginning at the induction of induced pluripotent stem cells differentiation into neuroprogenitor cells (Fig. 2 and 3). Differentiation of neuroprogenitor cell derived from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells into immature neurons at differentiation day 23 in the percentage of DCX positive cells was less by 9.1% (13.7 ± 3.2% vs 22.8 ± 3.2%, N=6 replicates, P=0.004) and 8.2% (14.6 ± 1.6% vs 22.8 ± 3.2%, N=6 replicates, P=0.011) respectively than the control, which was abolished by dantrolene (Fig. 2). Compared to the control, mature cortical neurons (Fig. 3) from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells decreased the percentage of Trb1 positive cells by 35.2% (23.5 ± 2.0% vs 58.8 ±12.3%, N=5 replicates, P<0.0001) and 15.8% (43.1± 6.9% vs 58.8 ±12.2%, N=5 replicates, P=0.022) respectively compared to control, an effect which was abolished by dantrolene (Fig. 3C). Using sonic hedgehog (Fig. 3D), we further examined the generation of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons [choline acetyltransferase positive cells (green) from induced pluripotent stem cells], since the deficient of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons has been considered a primary cause of memory loss and the basis of traditional treatments.19,29 Compared to the control, differentiation into particular basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (Fig. 3E) in the percentage of ChAT & MAP2 positive cells was less by 10.7% (22.2 ±2.6% vs 32.9 ±3.7%, N=5 replicates, P=0.004) and 9.2% (23.7 ±3.1% vs 32.9 ±3.6%, N=5 replicates, P=0.017) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells respectively, (Fig. 3F), which was also abolished by dantrolene.

Figure 2. Dantrolene ameliorated impairment of neuroprogenitor cells differentiation into immature neurons in Alzheimer’s disease cells.

Differentiation of neural progenitor cells into immature neurons (differentiation day 23) was significantly impaired in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD) and familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD), which was inhibited by dantrolene. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of stained immature neurons by doublecortin (DCX) (red), treated with or without dantrolene for 3 days, starting on induction day 0 from induced pluripotent stem cells. Scale bar=100μm. (B) Differentiations of both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.004) and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.011) were impaired compared to controls. However, the differentiations of both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.008) and familial Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.008) cells were enhanced after treatment with dantrolene. Cell type and treatment were significant sources of variation (F(2,30)=8.749, p=0.001 and F (1,30)=25.08, p<0.0001, respectively) using 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison tests. Data are represented by the means±SD from 6 independent experiments (n=6 for all groups). *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Figure 3. Dantrolene inhibited differentiation of neural progenitor cells into cortical neurons and basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease patient cells.

(A) Differentiation timeline of neural progenitor cells into mature cortical neurons (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of double-stained neurons with thyroid hormone receptor-b (Trb1, red) and microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP2, green). Scale bar=100μM. (C) The percent of Trb1 positive cells was significantly less in both human sporadic Alzheimer disease (SAD) (p<0.0001) and familial Alzheimer disease (FAD) cells (p=0.022) compared to control healthy subjects (CON) cells, but the sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells had significantly greater percentage of TrB1 positive cells after treatment with dantrolene (p<0.0001). Interaction, cell type, and treatment were significant sources of variation (F(2,24)=14.84, p<0.0001; F(2,24)=15.94, p<0.0001; F(1,24)=7.53, p=0.011), respectively. (D) Timeline for differentiation neural progenitor cells into mature basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of double-stained mature neurons by MAP2 (red) and choline acetyltransferase (CHAT) positive cells (green), with or without dantrolene treatment for 3 days starting from the induction of induced pluripotent stem cells differentiation into neurons. Scale bars=100μM. (F) The percentage of CHAT positive cells (basal forebrain cholinergic neurons) significantly decreased in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.004) and familial Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.017) cells, which was ameliorated by dantrolene treatment for familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.008) but not sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.067). Interaction, cell type, and treatment were significant sources of variation (F(2,24)=5.61, p=0.010; F(2,24)=6.27, p=0.006; F(1,24)=14.78,p=0.001, respectively). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. All data is represented as the mean ± SD from 5 independent experiments (n=5 for all groups). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001.

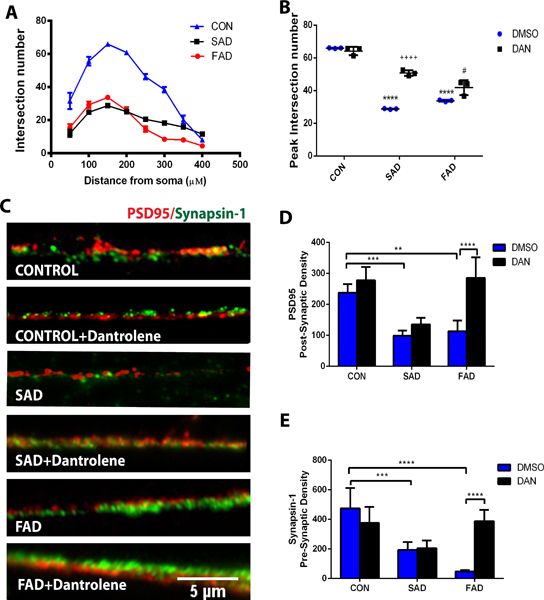

Dantrolene rescued the synaptogenesis impairment of neurons generated from the induced pluripotent stem cells of sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease patients

To determine the effects of dantrolene applied during the first three days of induced pluripotent stem cells induction period on synaptogenesis of induced pluripotent stem cells originated neurons, we quantified the numbers of intersections between dendrites and concentric circles of the cortical neurons, shown as the distance (μm) of the circles from the soma (Fig. 4A). Compared to the control neurons, the number of intersections (equivalent to synaptogenesis) were significantly less in cortical neurons generated from both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease patient induced pluripotent stem cells, and most dramatically by 52.5% (19.7 ± 6.2 vs 41.4 ± 19.3, N=3 replicates, P=<0.0001) and 57.2% respectively (17.7 ± 10.2 vs 41.4 ± 19.3 N=3 replicates, P<0.0001) at the distance around 150 μM from soma (Fig. 4A), which was inhibited by dantrolene, especially in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells (Fig. 4B). We further examined the effects of dantrolene on synaptic density by determining presynaptic marker synapsin-1 (green) and postsynaptic marker PSD95 (red), using a double immunostaining technique (Fig. 4C). Synapse density determined by either PSD95 (Fig. 4D) or synapsin-1 (Fig. 4E) was significantly less in cortical neurons generated from either sporadic Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells by 58.2% (99.0 ± 16.6 vs 237.0± 28.4 arbitrary units N=4 replicates, P=0.001) or familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells by 52.3% in PSD95 (113.0 ± 34.9 vs 237.0± 28.4 arbitrary units, N=5 replicates, P=0.001) and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells by 59.1% (194.0 ± 52.3 vs 474.5 ± 136.9 arbitrary units, N=4 replicates, P=0.001) or familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells by 89.8% in synapsin-1 (48.5 ± 9.1vs 474.5 ± 136.9 arbitrary units, N=5 replicates, P<0.0001), and both were inhibited by dantrolene in familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells.

Figure 4. Dantrolene inhibited impairment of dendrite intersection and synaptic density of neurons in Alzheimer’s disease cells.

Neural progenitor cells were differentiated into mature cortical neurons with insulin and dantrolene treatment was for 3 days starting from the induction of differentiation. The mean number of intersections between dendrites and concentric circles around the cortical neurons are shown as a function of the circle distance (μm) from the soma. (A) The number of intersections was significantly less in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD) and familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) cells, which was inhibited by dantrolene in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells. (B). The mean numbers of intersections at the distance around 150 μM from soma were less in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001) and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p<0.0001) compared to controls but were significantly greater in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001) and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p= 0.014) with dantrolene treatment. Interaction (F(2,12)=42.18, p<0.0001), cell type (F(2,12)=273.30, p<0.0001), and dantrolene treatment (F(1,12)=78.48, p<0.0001), were significant sources of variation. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test. (C) Synaptic density was determined by postsynaptic marker postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) (red) and presynaptic marker synapsin-1 (green) double immunostaining. Scale bar=100μM. (D) PSD95 density was significantly less in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.001) and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.001) compared to controls but was significantly greater in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p<0.0001) with dantrolene treatment. Interaction (F(2,23)=8.78,p=0.002), cell type (F(2,23)=25.36,p<0.0001), and dantrolene treatment F(1,23)=28.60, p<0.0001 ), were significant sources of variation. (E) Synpapsin-1 was also significantly less in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.001) and familial Alzheimer’s disease p<0.0001) cells and was significantly greater n familial Alzheimer’s disease cells treated with dantrolene (p<0.0001). Interaction (F(2,23)=18.12,p<0.0001), cell type (F(2,23)=21.46, p<0.0001), and dantrolene treatment (F(1,23)=7.18, p=0.013) were significant sources of variation. Data are represented by the mean±SD from at least 4 independent experiments: CON and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (N=5), sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells (N=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

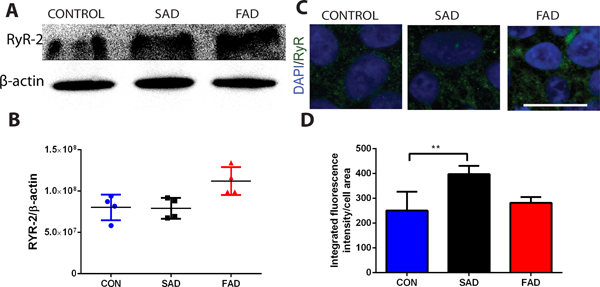

Type 2 ryanodine receptor was significantly greater in human Alzheimer’s disease than in control induced pluripotent stem cells.

For mechanisms studies, we first determined the expression of ryanodine receptor −2 using both immunoblotting (Fig. 5 A, B) and immunostaining (Fig. 5 C, D). Previous studies have demonstrated that ryanodine receptor −2 levels are abnormally elevated in Alzheimer’s disease patients8 and mice,9 contributing to Alzheimer’s disease pathology and cognitive dysfunction.5,6,17 Similarly, compared to that of healthy human subjects, ryanodine receptor −2/β-actin levels was greater by 60.4% (0.8± 0.2 vs. 0.5± 0.1, N=3, P=0.158) in familial Alzheimer’s disease (Fig. 5B.) and mean rank different by 11.1 (250.8 ± 75.7 vs 397.5 ± 33.6 arbitrary units, N=7 replicates, P=0.002) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. Increased type 2 ryanodine receptors in human Alzheimer’s disease cells.

Type 2 ryanodine receptors (ryanodine receptor-2) were more in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD) and familial Alzheimer disease (FAD) cells, and dramatically more in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells from patients (A and B), determined by immunoblotting (Western Blot). Similarly, Type 2 ryanodine receptors protein was significantly greater in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells determined by immunofluorescence staining (C, D). All data are Mean ± SD from 4 independent experiments (N=4 replicates, B) or 7 independent experiments (N=7 replicates, D). Data in B was nonparametric (D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test) and analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test (p=0.132) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison tests (P=0.158), compared to control healthy subjects (CON) cells. Data in D was also nonparametric and was analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test (p=0.002) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison tests. *P=0.020, **P=0.002. Scale bar: 25 μm (C).

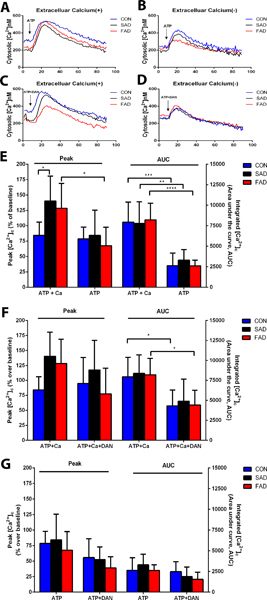

Dantrolene significantly inhibited ATP mediated abnormal elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]c) in induced pluripotent stem cells from both sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease patients.

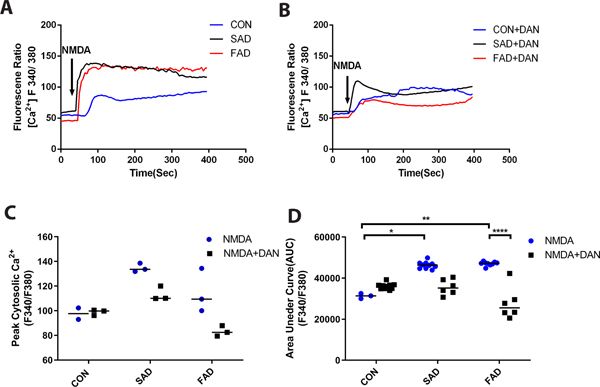

We further investigated the possible mechanisms by which neurogenesis and synaptogenesis were impaired in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells and were ameliorated by dantrolene. Consistent with this elevated ryanodine receptor-2 in Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells, the NMDA mediated elevation of integrated exposure (Fig. 6 A, D) were higher in familial Alzheimer’s disease and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells than in the normal control, which could be ameliorated by dantrolene (Fig. 6 B–D). When three types of cells are examined of the Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ store by treating them with ATP (30 μM), sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells showed significantly higher peak elevation of [Ca2+]c (percentage over baseline), (140.4 ± 40.2% vs. 84.1± 27.0%, N=5 replicates, P=0.049; 128.3 ± 40.6% vs 84.1 ± 27.0%, N=5 replicates, P=0.206,) which was abolished by removal of extracellular Ca2+and associated Ca2+ influx form extracellular space (Fig. 7 A, B, E) and pretreatment of dantrolene (30 μM) for 1 hour (Fig. 7 C, F). Without Ca2+ influx from extracellular space, ATP caused significantly lower overall elevation of [Ca2+]c in all three types of cells (Fig. 7E). In the absence of extracellular Ca2+ influx, dantrolene didn’t significantly inhibit ATP-mediated peak or overall elevation of [Ca2+]c in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (Fig. 7D and G).

Figure 6. Dantrolene significantly inhibited NMDA mediated elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]c) in induced pluripotent stem cells from Alzheimer’s disease patients.

NMDA (500 μM) induced greater overall exposure of the integrated cytosolic Ca2+ represented by area under curve (AUC) (A-D) in sporadic (SAD) and familiar (FAD) Alzheimer disease cells, (p=0.041 for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, p=0.008 for familial Alzheimer’s disease respectively), compared to normal human subjects (CON). Dantrolene (30 μM) ameliorated the NMDA mediated elevation of [Ca2+]c and AUC in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells, (p=0.436 for peak, p<0.0001 for AUC respectively) (B and D). All data are expressed as median [25th, 75th] from 3 independent experiments (N=3). Data in C was nonparametric and analyzed by the Kruskall-Wallis test (p=0.020) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison tests. Data for panel D was also nonparametric and analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test (p<0.001) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison tests. *p=0.041, **p=0.008, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 7. The effect of dantrolene on the ATP mediated elevation of cytosolic calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]c) in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from Alzheimer’s disease patients.

Having examined the data carefully via the use of numerical and graphical summaries, a two-way ANOVA was conducted to exam ATP (ATP + Ca2+) and cell type: control (CON), sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD), familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD). ATP (30 μM), in the presence of 1 mM extracellular calcium (ATP + Ca2+) (A, E), was a significant source of variation (F(1,35)=14.90, p=0.0005) for the peak cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations [Ca2+]c which were significantly higher in sporadic Alzheimer disease cells (p=0.049) compared to control cells. ATP, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ influx (ATP), caused significantly higher the ATP-induced peak [Ca2+]c in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.031) compared to familial Alzheimer’s disease cells in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ influx (ATP+Ca2+). (B, E). Furthermore, ATP with extracellular calcium (ATP+Ca2+) was a significant source of variation (F(1,35)=71.87, p<0.0001) for the integrated cytosolic Ca2+ (area under the curve, AUC), which was significantly less for control (p=0.0002), sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.005), and familial Alzheimer’s disease (p=<0.0001) cells compared to the same cells with ATP alone (ATP) (E). Dantrolene (30 μM) pretreatment of cells with ATP plus extracellular Ca2+ (ATP+Ca2++DAN) was a significant source of variation for Alzheimer’s disease cell type (F(2,42)=3.65, p=0.035) for the peak cytosolic [Ca2+]cthough no significant differences were detected between the groups(C, F). The addition of dantrolene (ATP+Ca2++DAN) was also a significant source of variation (F(1,40)=30.60,p<0.0001) for Alzheimer’s disease cell type for the AUC, which was significantly reduced for the controls (p=0.033) and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.015) compared to cells with just ATP + Ca2+(C, F). Dantrolene (30 μM) pretreatment of the cells with ATP in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (ATP+DAN) (D) was a significant source of variation (F(1,33)=10.01,p=0.003) on the peak cytosolic [Ca2+]c, though no significant differences were found between the groups (G), and the absence of Ca2+ was a significant source of variation (F(1,33)=5.95, p=0.020) on the AUC with no differences detected between groups (G). Peak and integrated Ca2+ concentrations are shown as a percentage of baseline from CON cells from normal human subjects. All data (E, F, G) are expressed as the mean±SD from at least 5 independent experiments (CON, n=6 replicates; sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, n=5 replicates; familial Alzheimer’s disease, n=8–9 replicates). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 Significance determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison tests.

Dantrolene ameliorated the decrease of lysosomal vATPase and acidity in induced pluripotent stem cells from Alzheimer’s disease patients.

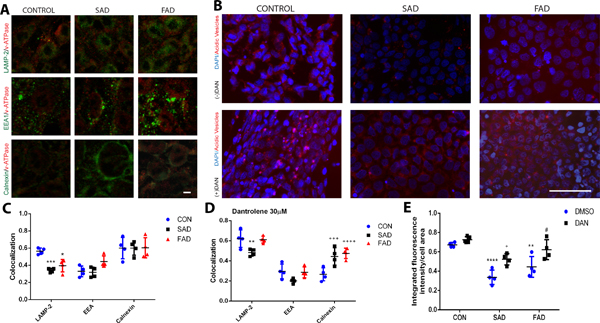

Decreased endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ concentrations in Alzheimer’s disease presenilin 1 mutation due to overactivation of ryanodine receptor impaired synthesis and secretion of vATPase from the endoplasmic reticulum into the lysosome, and subsequently decreased lysosome acidity and function.30 We have determined the changes of lysosome versus endoplasmic reticulum vATPase, as well as the lysosome acidity in various types of induced pluripotent stem cells. Location of vATPase was determined by double immunostaining and colocalization targeting lysosome (LAMP-2), endoplasmic reticulum (Calnexin) and endosome (EEA) (Fig. 8A), and the cellular acidity vehicle were determined by the lysotracker (Fig. 8B). The amount of lysosome vATPase was significantly less in induced pluripotent stem cells from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease by 39.3% (0.3 ± 0.02 vs. 0.6 ± 0.04, arbitrary units, N=4 replicates, P=0.001) and familial Alzheimer’s disease by 30.4% (0.4± 0.07 vs 0.6 ± 0.04, arbitrary units, N=4 replicates, P=0.010) (Fig. 8C, *Compared with the control), which could be inhibited by dantrolene, especially in familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells (Fig. 8D, *Compared with the control). Consistently, the cellular acidity vehicle was significantly decreased by 49.3% (0.3 ± 0.1 vs 0.7 ± 0.02, arbitrary units, N=4 replicates, P<0.0001) and 34.3% (0.4 ± 0.1 vs 0.7± 0.02, arbitrary units, N=4 replicates, P=0.004) respectively in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells compared to that of the normal control, which were also significantly inhibited by dantrolene (Fig. 8E, *Compared with the control,+ Compared with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease,# Compared with familial Alzheimer’s disease .).

Figure 8. Lysosomal ATPase and acidity in neurons derived from Alzheimer’s disease patients were less than in control cells.

(A) Colocalization of V-ATPase (red) was measured using immunostaining with specific markers targeting lysosomes (LAMP-2, green), endosomes (EEA, green), and endoplasmic reticulum (Calnexin, green), in induced pluripotent stem cells of healthy human subjects (CON), sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD) or familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) patients. (B) Cell acidity was measured by lysotracker-positive acidic vehicles (red) in control, sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (DAPI, blue). (C) V-ATPase in lysosomes (LAMP-2) was significantly lower in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.001) and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.010) than controls. There was significant source of variation for interaction (F(4,23)=4.35, p=0.008) and organelle type (F(2,23)=29.15, p<0.0001). (D) With the addition of dantrolene (30 μM), V-ATPase in lysosomes (LAMP-2) in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells was no longer significantly reduced (p=0.965) but remained significantly lower in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.007) compared to controls. Besides, v-ATPase in the endoplasmic reticulum (calnexin) of the controls was significantly reduced compared to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.001) and familial Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001) cells. There was significant source of variation for interaction (F(4,27)=8.66,p=0.0001), organelle type (F(2,27)=79.49, p<0.0001), and cell type (F(2,27)=5.96, p=0.007). (E) Lysotracker-positive acidic vesicles were significantly lower in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001), familial Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.0004) compared to control cells. Dantrolene significantly increased also- tracker-positive acidic vesicles in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.025) and familial Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.036) cells compared to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Cell type and dantrolene were significant sources of variation (F(2,19)=29.88, p<0.0001; F(1,19)=23.16, p=0.0001, respectively). All data are expressed as the mean±SD from 4 independents (n=4 replicates for all groups) and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Dantrolene promoted autophagy activity in induced pluripotent stem cells from Alzheimer’s disease patients.

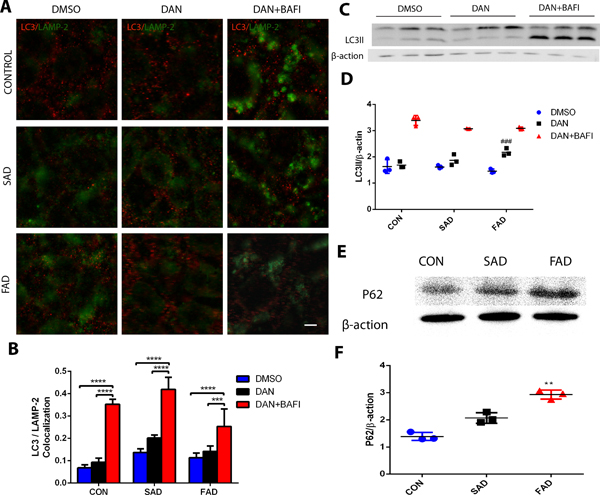

We further determined the effects of dantrolene on autophagy, considering the important role of lysosome in autophagy flux. The overall activity indicated by overall cellular level of autophagy biomarker LC3II was not significantly different among the three types of induced pluripotent stem cells (Fig. 9 A–C). However, dantrolene treatment induced higher LC3II level by 42.9% (0.2 ± 0.01 vs. 0.1 ± 0.02, arbitrary units, N=5, P=0.348) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (Fig. 9B) and by 27.3% (0.1 ± 0.02 vs. 0.1 ± 0.02, ratio of LC3 II/β-actin, N=3 replicates, P=0.0004) in familial Alzheimer’s disease (Fig. 9C. #Compared with familial Alzheimer’s disease) induced pluripotent stem cells respectively, which could be further elevated by the co-treatment with bafilomycin, an agent that impaired autophagy flux (Fig. 9 B, C). This suggests that dantrolene promoted autophagy induction, rather than impairing autophagy flux. The impaired autophagy flux in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells was further supported by the significantly elevated ratio of p62/β-actin mean rank different by 3 (1.6 ± 0.1 vs. 1.6 ± 0.3, N=3 replicates, P=0.359) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and by 6 (1.5 ± 0.1 vs. 1.6 ± 0.3, arbitrary units, N=3 replicates, P=0.015) in familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells respectively (Fig. 9D, *Compared with the control).

Figure 9. Dantrolene increased LC3II levels in induced pluripotent stem cells from Alzheimer’s disease patients.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical images and (C) representative Western blots of LC3II (red) in lysosomes (LAMP2, green) in induced pluripotent stem cells from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD), familial Alzheimer disease (FAD) and healthy human controls (CON), with Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), dantrolene, or dantrolene plus bafilomycins (BAFI). (B) Quantitation of the double-labeled immunostained cells showed that dantrolene with bafilomycins resulted in significantly greater LC3II in lysosomes (LAMP-2) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001, p<0.0001), familial Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001, p=0.001), and CON (p<0.0001) cells compared to dimethyl sulfoxide or dantrolene, respectively. There were significant sources of variation in interaction (F(4,35)=8.18, p<0.0001), cell type (F(2,35)=24.08, p<0.0001), and treatment (F(2,35)=177.00, p<0.0001) using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test. (D) Quantitation of Western blots similarly showed that dantrolene with bafilomycins resulted in significantly greater LC3II in lysosomes (LAMP-2) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001, p<0.0001), familial Alzheimer’s disease (p<0.0001, p<0.0001), and control (p<0.0001, p<0.0001) cells compared to used dimethyl sulfoxide or dantrolene alone, respectively. familial Alzheimer’s disease cells treated with dantrolene were also significantly increased (p=0.0004) compared to familial Alzheimer’s disease treated with dimethyl sulfoxide cells. Interaction (F(4,18)=6.92, p=0.002) and treatment (F(2,18)=303.40, p<0.001) were significant sources of variation using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test. (E) Representative Western blot of P62 levels in control, sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells. (F) Quantitation of P62 Western blots found that this marker of cellular stress is significantly greater in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells (p=0.015) compared to control using the Kruskal-Wallis test (p=0.004) followed by Dunn’s multiple correct tests. All data are expressed as the mean±SD from at least 3 independent experiments (n=3 replicates for all groups). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, *** P<0.001, ****P<0.0001

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that neurogenesis from neuroprogenitor cells to common cortical and Alzheimer’s disease-specific deficient basal forebrain cholinergic neurons was significantly impaired in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients, compared to in healthy human subject, which could be inhibited by dantrolene. Also, dantrolene significantly inhibited synaptogenesis impairment in cortical neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients. In term of mechanisms study, the ryanodine receptor-2 numbers in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells were abnormally increased, which contributed to the significant abnormal elevation of [Ca2+]c by Ca2+ influx from extracellular space31–35. On the other hand, the abnormal Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum aggravated Ca2+ influx via capacitive calcium entry36, forming a vicious cycle to increase [Ca2+]c and mitochondria Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m), with simultaneous abnormal decrease of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]er). All above pathological Ca2+ dysregulation in cell lines derived from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients contributed to the impairment of autophagy function, decrease of cell survival and impairment of neurogenesis and synaptogenesis. Consistently, dantrolene significantly ameliorated the above pathological Ca2+ dysregulation and therefore neuroprotective in the cell lines from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients5,6,17,18

Recent studies indicate the important role of neurogenesis and synaptogenesis in cognitive function.37 This is especially true in Alzheimer’s disease because of an existing deficiency of memory formation-related neurons, such as basal forebrain cholinergic neurons.19 Although the mechanisms remain unclear, neurogenesis/synaptogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease are significantly impaired, contributing to cognitive dysfunction.11,38 A physiological intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis plays an important role in neurogenesis/synaptogenesis and synapse function, while excessive Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum through overactivation of ryanodine receptor in Alzheimer’s disease disrupts neurogenesis/synaptogenesis, which in turn, impairs synapse and cognitive function. Theoretically, a method/approach to correct the disrupted intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis would inhibit impaired neurogenesis/synaptogenesis, synapse, and cognitive dysfunction. By targeting the upstream pathological overactivation of ryanodine receptor in Alzheimer’s disease, dantrolene is theoretically a good candidate to correct the disrupted intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and associated neuropathology and could be therapeutic. In fact, dantrolene did inhibit the NMDA receptor activation mediated Ca2+ dysregulation, impaired neurogenesis/synaptogenesis and ameliorate lysosome dysfunction in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells/neuroprogenitor cell /neurons in this study. With its potency to inhibit impaired neurogenesis/synaptogenesis and to ameliorate the neurodegeneration in different types of neurodegenerative diseases,18,21 and its relatively tolerable side effects even after chronic administration,39 dantrolene is expected to be therapeutic on both neuropathology and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease patients and further clinical trials are warranted.

Presenilin 1 mutation in familial Alzheimer’s disease causes ryanodine receptor overactivation and Ca2+ dysregulation, resulting in worsened amyloid pathology, inflammation, neurodegeneration and synapse dysfunction.4,40 Comparatively, much less is known about the Ca2+ dysregulation and mechanisms in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells, especially its role in the neurogenesis. The results from this study suggest that similar Ca2+ dysregulation caused by overactivation of ryanodine receptor and excessive Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum may also exists in the sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells from patients, which can be corrected by dantrolene. Previous studies implicated the role of glutamate excitotoxicity, especially the NMDA overactivation and associated Ca2+ dysregulation, on neurodegeneration, amyloid pathology and other neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease.9,41 This has been the fundamental basis for the US Food and Drug Administration approval of last Alzheimer’s disease treatment drug, Memantine.42 Dantrolene has been demonstrated to ameliorate the majority of NMDA mediated elevation of [Ca2+]c (up to 70%) in primary cortical neurons.43 Because previous studies have also suggested that dantrolene could inhibit NMDA receptor mediated Ca2+ influx,44 it is possible that the inhibition of the NMDA receptor by dantrolene contributes to its amelioration on the elevation of [Ca2+]c. In the comparison of similar effects of removal extracellular Ca2+ influx and use of dantrolene, it is plausible to assume that dantrolene ameliorated ATP mediated [Ca2+]c elevation by primary inhibition of Ca2+ influx from extracellular space, although the inhibition of ryanodine receptor mediated capacitive calcium entry may play a role on Ca2+ influx. Although additional experiments examining the exact Ca2+ channels on plasma membrane (e.g. different types of voltage-dependent calcium channels, glutamate receptors, Orail 1 receptors etc.) involved for ATP mediated elevation of [Ca2+]c and the effects of dantrolene is beyond the scope of current study and should be investigated furthermore in the future. Regardless of the detailed mechanisms, dantrolene can inhibit NMDA overactivation on both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells, which contributes to its beneficial effects on ameliorating the impaired neurogenesis/synaptogenesis in induced pluripotent stem cells/neuroprogenitor cell /neurons from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients. It is important to note that dantrolene is also neuroprotective in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells because sporadic Alzheimer’s disease accounts for most Alzheimer’s disease patients. In a further step, these results need continuous confirmation in multiple cell lines from induced pluripotent stem cells of different sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease patients. Although the genetic background may not be the same in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease, they seem to share a common mechanism on the disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and associated impairment of neurogenesis/synaptogenesis, in addition to the Ca2+ dysregulation mediated amyloid, Tau pathology and neurodegeneration in previous studies.45

Normal and physiological autophagy function play important roles in many cell functions, including neurogenesis and synaptogenesis46, while impaired physiological autophagy may promote apoptosis and pathological autophagy may cause autophagic cell death directly.47 Disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, especially abnormal Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum via ryanodine receptor or inositol triphosphate receptor, contributed to both impaired physiological autophagy or pathological autophagic cell death.47 Altered and/or impaired autophagy function have been demonstrated in familial Alzheimer’s disease 30. Although the mechanisms are not clear, Ca2+ dysregulation contributes to impaired autophagy function in Alzheimer’s disease, because Ca2+ is an important messenger in the regulation of autophagy.45 Activation of Inositol triphosphate receptor and Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum can induce autophagy by a cytosolic Ca2+-dependent way48 or inhibit autophagy via mitochondrial pathway to increase production of ATP.49 Ryanodine receptor overactivation, especially ryanodine receptor −3, impairs autophagy flux at lysosome level50 and promotes autophagy cell death (ACD)51. The results from this study are consistent with the previous finding that abnormally elevated ryanodine receptor-2 (Fig. 5) and resultant Ca2+ dysregulation (Fig. 6, 7) in Alzheimer’s disease cells were associated with the impaired lysosome acidity and function (Fig. 8). Autophagy flux was consistently impaired in Alzheimer’s disease cells, but dantrolene seemed to primarily promote autophagy activity, although it also ameliorated impaired lysosome acidity and function. (Fig. 8, 9). It is reasonable to associate dantrolene mediated inhibition of impaired neurogenesis/synaptogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease cells with its ability to promote overall autophagy activity and to ameliorate the impaired lysosome function.

Due to the lack of well recognized cell or animal models of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, the autophagy function and its relationship with intracellular Ca2+ regulation is much less defined in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. We have demonstrated in this study that, like in familial Alzheimer’s disease cells,30 the lysosome acidity and function was also impaired in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells, which was rescued by dantrolene, suggesting a role of calcium dysregulation in disrupting the autophagy function in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells. Additionally, dantrolene can promote autophagy induction and relieve impaired lysosome function in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells. In combination with its beneficial effects in inhibiting impaired neurogenesis/synaptogenesis in this study, it is reasonable to assume that the ability of dantrolene to correct disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis contributes to its beneficial effects on autophagy function, neurogenesis/synaptogenesis in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease cells.

Cholinergic cortical neurons in the prefrontal cortex play important roles in the formation of memory and has been considered major deficient neurons in Alzheimer’s disease.19 The majority of current symptom relieving drugs for Alzheimer’s disease are the cholinesterase inhibitors, aiming to raise level of presynaptic acetylcholine, antagonizing the effects of deficiency of cholinergic cortical neurons.29 The results in this study indicated a reduced neurogenesis on cholinergic neurons, which can be inhibited by dantrolene. The beneficial effects of dantrolene to restore cholinergic cortical neurons theoretically make the drug a potential treatment of cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease, especially in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Furthermore, the inhibition of impaired synaptogenesis on cholinergic neurons also help to improve synapse and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease. More translational studies are needed in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease animal model or those models more translational to human Alzheimer’s disease to promote dantrolene to be a potential future drug treatment for Alzheimer’s disease patients.52 Because neuroprotection of dantrolene is dose-dependent, a method or approach to improve dantrolene penetration into CNS will be very helpful to promote dantrolene use for neuroprotection of various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and stroke.53

This study has following limitations: 1). Each sporadic Alzheimer’s disease/familial Alzheimer’s disease cell line is only from one patient and more cell lines from different patients are needed to strengthen the finding and confirm the conclusion, especially on data with less consistency between sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells; 2). The mechanisms of dantrolene neuroprotection is primarily based on its inhibition of ryanodine receptor, but other possible effects, such as on NMDA receptors, need to be clarified in future studies; 3). Lack of studies on synapse function by electrophysiology studies, which contribute to the cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease.

In conclusion, dantrolene significantly ameliorated impaired neurogenesis and synaptogenesis in both sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and familial Alzheimer’s disease cells from patients, which was associated with its effects to restore the intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and to ameliorate lysosomal dysfunction and promote autophagy activity, calling for further investigation of using dantrolene to treat Alzheimer’s disease patients in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the lab of John A Kessler, MD at Simpson Querrey Center for Neurogenetics, Northern Western University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois for providing us the induced pluripotent stem cells from health human subjects or Alzheimer’s disease patients. We thank Paola Pizzo, PhD of the Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Padova, Padova, Italy for providing us the recombinant cytosolic aequorin for Ca2+ measurement. We thank Megha Vipani, MD candidate from the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, Virginia for manuscript editing. We appreciate the valuable discussion and statistical analysis assistance from Maryellen Eckenhoff, PhD and Roderic Eckenhoff, MD from the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Funding

Supported by grants to HW from the NIH (R01GM084979, R01AG061447).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests

Dr. Huafeng Wei was once a member of the Advisory Board of Eagle Pharmaceutical Company for a one-day meeting in 2017 and the contract expired now. Eagle Pharmaceutical Company produce and sale of Ryanodex, a new formula of dantrolene. Partial results of this manuscript have been included in a US provisional patent application titled “Intranasal Administration of Dantrolene for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease” filed on June 28, 2019 (Serial number 62/868,820) by the University of Pennsylvania Trustee. Two of the co-authors, all employees of the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Huafeng Wei and Dr. Ge Liang, are listed as inventors of the provisional patent application. The patent application is also part of the research collaboration agreement between University of Pennsylvania and Eagle Pharmaceutical Company. The dantrolene used in this study is purchased from the Sigma Company.

No other authors declare conflicts of interests.

This research work was performed in Dr. Wei’s lab and should be attributed to University of Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Sala Frigerio C, De Strooper B: Alzheimer’s Disease Mechanisms and Emerging Roads to Novel Therapeutics. Annu Rev Neurosci 2016; 39: 57–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allgaier M, Allgaier C: An update on drug treatment options of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2014; 19: 1345–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H, Sun S, Herreman A, De SB, Bezprozvanny I: Role of presenilins in neuronal calcium homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2010; 30: 8566–8580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung KH, Shineman D, Muller M, Cardenas C, Mei LJ, Yang J, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Lee VMY, Foskett JK: Mechanism of Ca2+ disruption in Alzheimer’s disease by presenilin regulation of InsP(3) receptor channel gating. Neuron 2008; 58: 871–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakroborty S, Briggs C, Miller MB, Goussakov I, Schneider C, Kim J, Wicks J, Richardson JC, Conklin V, Cameransi BG, Stutzmann GE: Stabilizing endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) Channel Function as an Early Preventative Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e52056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng J, Liang G, Inan S, Wu Z, Joseph DJ, Meng Q, Peng Y, Eckenhoff MF, Wei H: Dantrolene ameliorates cognitive decline and neuropathology in Alzheimer triple transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett. 2012; 516: 274–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelliher M, Fastbom J, Cowburn RF, Bonkale W, Ohm TG, Ravid R, Sorrentino V, O’Neill C: Alterations in the ryanodine receptor calcium release channel correlate with Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary and beta-amyloid pathologies. Neuroscience.92(2):499–513 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruno AM, Huang JY, Bennett DA, Marr RA, Hastings ML, Stutzmann GE: Altered ryanodine receptor expression in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012; 33: 1001. e1–1001. e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goussakov I, Miller MB, Stutzmann GE: NMDA-mediated Ca(2+) influx drives aberrant ryanodine receptor activation in dendrites of young Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2010; 30: 12128–12137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demars M, Hu YS, Gadadhar A, Lazarov O: Impaired neurogenesis is an early event in the etiology of familial Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic mice. J Neurosci Res. 2010; 88: 2103–2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez JJ, Jones VC, Tabuchi M, Allan SM, Knight EM, LaFerla FM, Oddo S, Verkhratsky A: Impaired adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PloS one 2008; 3: e2935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreau M, Neant I, Webb SE, Miller AL, Riou JF, Leclerc C: Ca(2+) coding and decoding strategies for the specification of neural and renal precursor cells during development. Cell Calcium 2016; 59: 75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins JP, Price J: Human induced pluripotent stem cells as a research tool in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Med 2017; 47: 2587–2592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause T, Gerbershagen MU, Fiege M, Weisshorn R, Wappler F: Dantrolene--a review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use and new developments. Anaesthesia 2004; 59: 364–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang L, Wei H: Dantrolene, a treatment for Alzheimer disease? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015; 29: 1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z, Yang B, Liu C, Liang G, Liu W, Pickup S, Meng Q, Tian Y, Li S, Eckenhoff MF, Wei H: Long-term Dantrolene Treatment Reduced Intraneuronal Amyloid in Aged Alzheimer Triple Transgenic Mice. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015; 29: 184–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oules B, Del PD, Greco B, Zhang X, Lauritzen I, Sevalle J, Moreno S, Paterlini-Brechot P, Trebak M, Checler F, Benfenati F, Chami M: Ryanodine receptor blockade reduces amyloid-beta load and memory impairments in Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Neurosci. 2012; 32: 11820–11834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakroborty S, Kim J, Schneider C, West AR, Stutzmann GE: Nitric oxide signaling is recruited as a compensatory mechanism for sustaining synaptic plasticity in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2015; 35: 6893–6902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan L, Bhattacharyya BJ, Belmadani A, Pan L, Miller RJ, Kessler JA: Stem cell derived basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from Alzheimer’s disease patients are more susceptible to cell death. Mol Neurodegener. 2014; 9: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israel MA, Yuan SH, Bardy C, Reyna SM, Mu Y, Herrera C, Hefferan MP, Van Gorp S, Nazor KL, Boscolo FS, Carson CT, Laurent LC, Marsala M, Gage FH, Remes AM, Koo EH, Goldstein LS: Probing sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease using induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2012; 482: 216–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiao H, Li Y, Xu Z, Li W, Fu Z, Wang Y, King A, Wei H: Propofol Affects Neurodegeneration and Neurogenesis by Regulation of Autophagy via Effects on Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(3):490–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren G, Zhou Y, Liang G, Yang B, Yang M, King A, Wei H: General Anesthetics Regulate Autophagy via Modulating the Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor: Implications for Dual Effects of Cytoprotection and Cytotoxicity. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Livesey FJ: Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cerebral cortex neurons and neural networks. Nat Protoc. 2012; 7: 1836–1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bissonnette CJ, Lyass L, Bhattacharyya BJ, Belmadani A, Miller RJ, Kessler JA: The controlled generation of functional basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2011; 29: 802–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Weick JP, Liu H, Krencik R, Zhang X, Ma L, Zhou G-m, Ayala M, Zhang S-C: Medial ganglionic eminence–like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells correct learning and memory deficits. Nat Biotechnol. 2013; 31: 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A, Pozzan T, Pizzo P: Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015: 201504880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonora M, Giorgi C, Bononi A, Marchi S, Patergnani S, Rimessi A, Rizzuto R, Pinton P: Subcellular calcium measurements in mammalian cells using jellyfish photoprotein aequorin-based probes. Nat Protoc 2013; 8: 2105–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollomon MG, Gordon N, Santiago-O’Farrill JM, Kleinerman ES: Knockdown of autophagy-related protein 5, ATG5, decreases oxidative stress and has an opposing effect on camptothecin-induced cytotoxicity in osteosarcoma cells. BMC Cancer 2013; 13: 500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue W, Li Y, Zhang T, Jiang M, Qian Y, Zhang M, Sheng N, Feng S, Tang K, Yu X, Shu Y, Yue C, Jing N: ESC-Derived Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Neurons Ameliorate the Cognitive Symptoms Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease in Mouse Models. Stem Cell Reports 2015; 5: 776–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JH, Yu WH, Kumar A, Lee S, Mohan PS, Peterhoff CM, Wolfe DM, Martinez-Vicente M, Massey AC, Sovak G, Uchiyama Y, Westaway D, Cuervo AM, Nixon RA: Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell 2010; 141: 1146–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Sun C: Calcium and Neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurosci. 2010; 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakroborty S, Stutzmann GE: Early calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease: setting the stage for synaptic dysfunction. Sci China Life Sci 2011; 54: 752–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camandola S, Mattson MP: Aberrant subcellular neuronal calcium regulation in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1813: 965–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katayama T, Imaizumi K, Manabe T, Hitomi J, Kudo T, Tohyama M: Induction of neuronal death by endoplasmic reticulum stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J Chem.Neuroanat. 2004; 28: 67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bordji K, Becerril-Ortega J, Buisson A: Synapses, NMDA receptor activity and neuronal Abeta production in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Neurosci. 2011; 22: 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herms J, Schneider I, Dewachter I, Caluwaerts N, Kretzschmar H, Van Leuven F: Capacitive calcium entry is directly attenuated by mutant presenilin-1, independent of the expression of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. .278(4):2484–9 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anacker C, Hen R: Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive flexibility - linking memory and mood. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017; 18: 335–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haughey NJ, Nath A, Chan SL, Borchard A, Rao MS, Mattson MP: Disruption of neurogenesis by amyloid β‐peptide, and perturbed neural progenitor cell homeostasis, in models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2002; 83: 1509–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng J, Liang G, Inan S, Wu Z, Joseph D, Meng Q, Peng Y, Eckenhoff M, Wei H: Early and chronic treatment with dantrolene blocked later learning and memory deficits in older Alzheimer’s triple transgenic mice. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2011; 7: e67 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stutzmann GE, Smith I, Caccamo A, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Parker I: Enhanced ryanodine receptor recruitment contributes to Ca2+ disruptions in young, adult, and aged Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2006; 26: 5180–5189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi Y, Wang Y, Wei H: Dantrolene : From Malignant Hyperthermia to Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2018. June 19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKeage K: Memantine: a review of its use in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. CNS.Drugs 2009; 23: 881–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frandsen A, Schousboe A: Mobilization of dantrolene-sensitive intracellular calcium pools is involved in the cytotoxicity induced by quisqualate and N-methyl-D-aspartate but not by 2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazol-4-yl)propionate and kainate in cultured cerebral cortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992; 89: 2590–2594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makarewicz D, Zieminska E, Lazarewicz JW: Dantrolene inhibits NMDA-induced 45Ca uptake in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Neurochem Int. 2003; 43: 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Shi Y, Wei H: Calcium Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Target for New Drug Development. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2017; 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cecconi F, Di BS, Nardacci R, Fuoco C, Corazzari M, Giunta L, Romagnoli A, Stoykova A, Chowdhury K, Fimia GM, Piacentini M: A novel role for autophagy in neurodevelopment. Autophagy. 2007; 3: 506–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang M, Wei H: Anesthetic neurotoxicity: Apoptosis and autophagic cell death mediated by calcium dysregulation. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2017; 60: 59–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong Y, Song F: Intracellular calcium signaling regulates autophagy via calcineurin-mediated TFEB dephosphorylation. Autophagy 2015; 11: 1192–1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cardenas C, Miller RA, Smith I, Bui T, Molgo J, Muller M, Vais H, Cheung KH, Yang J, Parker I, Thompson CB, Birnbaum MJ, Hallows KR, Foskett JK: Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell 2010; 142: 270–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vervliet T, Pintelon I, Welkenhuyzen K, Bootman MD, Bannai H, Mikoshiba K, Martinet W, Nadif Kasri N, Parys JB, Bultynck G: Basal ryanodine receptor activity suppresses autophagic flux. Biochem Pharmacol 2017; 132: 133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung KM, Jeong EJ, Park H, An HK, Yu SW: Mediation of Autophagic Cell Death by Type 3 Ryanodine Receptor (RyR3) in Adult Hippocampal Neural Stem Cells. Front Cell Neurosci 2016; 10: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuner SM, Heuer SE, Huentelman MJ, O’Connell KMS, Kaczorowski CC: Harnessing Genetic Complexity to Enhance Translatability of Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models: A Path toward Precision Medicine. Neuron 2019; 101: 399–411 e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inan S, Wei H: The cytoprotective effects of dantrolene: a ryanodine receptor antagonist. Anesth Analg. 2010; 111: 1400–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.