Abstract

Genes and neural circuits coordinately regulate animal sleep. However, it remains elusive how these endogenous factors shape sleep upon environmental changes. Here, we demonstrate that Shaker (Sh)-expressing GABAergic neurons projecting onto dorsal fan-shaped body (dFSB) regulate temperature-adaptive sleep behaviors in Drosophila. Loss of Sh function suppressed sleep at low temperature whereas light and high temperature cooperatively gated Sh effects on sleep. Sh depletion in GABAergic neurons partially phenocopied Sh mutants. Furthermore, the ionotropic GABA receptor, Resistant to dieldrin (Rdl), in dFSB neurons acted downstream of Sh and antagonized its sleep-promoting effects. In fact, Rdl inhibited the intracellular cAMP signaling of constitutively active dopaminergic synapses onto dFSB at low temperature. High temperature silenced GABAergic synapses onto dFSB, thereby potentiating the wake-promoting dopamine transmission. We propose that temperature-dependent switching between these two synaptic transmission modalities may adaptively tune the neural property of dFSB neurons to temperature shifts and reorganize sleep architecture for animal fitness.

Subject terms: Behavioural genetics, Sleep, Neural circuits

Ji-hyung Kim and Yoonhee Ki et al. show that low temperatures suppress sleep in Drosophila by increasing GABA transmission in Shaker-expressing GABAergic neurons projecting onto the dorsal fan-shaped body, while high temperatures potentiate dopamine-induced arousal by reducing GABA transmission. This study highlights a role for Shaker in sleep modulation via a temperature-dependent switch in GABA signaling.

Introduction

Sleep is an essential behavior that is manifested by highly conserved physiological features across animal species. These include behavioral quiescence in a sleep-specific posture, elevated arousal threshold, daily regulation of the sleep-wake cycle by circadian clocks, and sleep homeostasis. Nonetheless, the evolutionary distance between different animal species does not necessarily correlate with similarities or differences in their daily sleep behaviors. It is thus likely that animal sleep has adaptively evolved according to various ecological circumstances in addition to the sleep-regulatory components encoded by each genome.

A Drosophila model of sleep has been established to understand how genes, neurotransmitters, and neural activity collectively regulate sleep behaviors1–3. A missense mutation, minisleep (mns), in the gene encoding the evolutionarily conserved voltage-gated potassium channel Shaker (Sh) has been identified via a forward genetic screen4. This mutation is known to cause wakefulness. Sh-dependent sleep regulation is further supported by the short sleep phenotypes observed in mutants of two Sh-related genes, Hyperkinetic (Hk) and sleepless (sss). HK and SSS proteins associate with the SH channel and potentiate its activity or stability5–9. Accordingly, the SH complex represents one of the major sleep-promoting pathways in Drosophila, although Sh-independent sleep regulation by sss has also been reported10. Another sleep-promoting pathway involves the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Indeed, pharmacological enhancement of GABA transmission has been shown to promote sleep11,12. In addition, genetic manipulation of GABA receptors in a subset of Drosophila neurons disrupts specific aspects of daily sleep behaviors13–16 and masks the sleep-promoting effects of a GABA receptor agonist12.

On the other hand, two monoamine neurotransmitters, dopamine (DA) and octopamine (OA, closely related to norepinephrine in mammals), contribute to wake-promoting pathways in Drosophila. Transgenic excitation of either dopaminergic or octopaminergic neurons induces insomnia-like behaviors with distinguishable daily sleep profiles17–19. A specific subset of sleep-regulatory neurons has been mapped; these neurons express subtypes of DA or OA receptors, respectively, and mediate the wake-promoting effects of their ligands18–21. In particular, two groups of wake-promoting dopaminergic neurons, PPL1 and PPM3, have been shown to project onto sleep-promoting dorsal fan-shaped body (dFSB) neurons in the central complex of adult fly brain18,19. D1-like DA receptors, Dop1R1 and Dop1R2, transmit the inhibitory dopaminergic input to dFSB neurons and suppress their sleep-promoting neural activity18,19,21. Sleep state further modulates sleep-regulatory inputs into dFSB neurons or the excitability of dFSB neurons, suggesting their roles in sleep homeostasis18,22,23. Accordingly, dFSB neurons are considered as analogous to sleep-promoting ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) in mammalian brains18,24.

In fact, the opposing effects of the voltage-dependent Sh and voltage-independent leak potassium channel Sandman set the electrical property of dFSB neurons21. Sh depletion in dFSB neurons suppresses the generation of repetitive neural activity while negligibly affecting their DA responses. Consistently, dFSB-specific depletion of the SH complex, including HK and SSS, decreases daily sleep amount. By contrast, Sandman depletion in dFSB neurons blocks their entry into electrical quiescence upon prolonged DA transmission, thereby inducing sleep. Sleep need is further sensed by the elevation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and the subsequent oxidation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate bound to HK25. The latter leads to high-frequency spiking in dFSB neurons that induces sleep, underlying their role in sleep homeostasis.

While genetic and neural components of sleep regulation have been defined, the mechanisms by which endogenous sleep-regulatory pathways sense external sleep-modulatory cues and adjust sleep behaviors remain elusive. Temperature is an environmental factor that affects sleep acutely and reversibly. Animals keep a 24-hour periodicity in their circadian rhythms over a physiological range of ambient temperatures. This phenomenon is an important clock property of circadian rhythms and is known as temperature compensation26. By contrast, mid-day siestas and nighttime insomnia in hot summer exemplify the temperature-dependent plasticity of sleep in humans. These adaptive changes in sleep-wake cycles are also present in Drosophila27–29. Both circadian clock-dependent and -independent mechanisms are implicated in shaping the sleep architecture in immediate response to heat30,31. Nonetheless, genetic and neural bases underlying the clock-independent control of sleep by temperature or the long-term effects of temperature shifts on sleep behaviors are largely unknown.

Results

Sh mutants display temperature-sensitive short sleep

To understand how ambient temperature affects sleep behaviors in Drosophila, we designed a behavioral test with a temperature shift (Fig. 1a). We first measured baseline sleep in individual flies at 21 °C in 12-h light:12-h dark (LD) cycles. We then elevated the ambient temperature to 29 °C and continuously monitored their sleep behaviors. This experimental setup allowed us to trace the temperature-dependent behavioral plasticity in individual flies. In addition, we could distinguish between immediate arousal responses to the temperature shift at midnight (i.e., 4 h after lights-off) and chronic effects of the high temperature on baseline sleep in the following days.

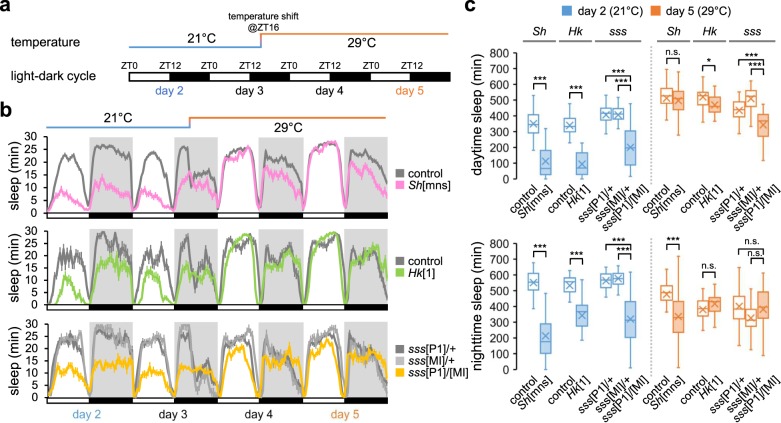

Fig. 1. Sh and Hk mutants display short sleep phenotypes in a temperature-sensitive manner.

a A schematic of 12-h light (white bars):12-h dark (black bars) cycles and a temperature shift for monitoring temperature-adaptive sleep behaviors. b Sleep profiles of Sh (pink line, n = 68), Hk (green line, n = 27), sss mutants (yellow line, n = 29), and their controls (gray lines, n = 20–122). Sleep behaviors were analyzed in individual male flies and averaged for each genotype. Error bars indicate SEM. c Box plots represent the total amounts of L or D sleep on day 2 (21 °C, blue boxes) versus day 5 (29 °C, orange boxes) (n = 20–122). Each box plot ranges from lower Q1 to upper Q3 quartile; crosses and horizontal lines inside each box indicate mean and median values, respectively; whiskers extend to minimum or maximum values of 1.5 × interquartile range. n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 as determined by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA, Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

In wild-type flies, the temperature shift from 21 to 29 °C acutely suppressed nighttime sleep (D sleep); however, the daily amount of baseline sleep subsequently became comparable between 21 and 29 °C (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). More notable effects of temperature were observed on sleep bout numbers and average sleep bout length (ABL). In particular, high temperature increased sleep bout numbers (Supplementary Fig. 1c) while substantially shortening nighttime ABL (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Accordingly, daily sleep architecture was modulated at 29 °C by long daytime sleep (L sleep) and D sleep fragmentation (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Additional change included longer latency to D sleep onset at 29 °C (Supplementary Fig. 1e). The temperature-driven plasticity of sleep behaviors was consistent with nocturnal activities in wild-type flies at high temperature27–29 (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Nonetheless, our assessment of waking activity (i.e., activity counts per minute awake) suggested that ambient temperatures were less likely to have an effect on locomotion per se (Supplementary Fig. 1g).

We next examined whether mutations in sleep-regulatory genes could affect sleep behaviors differentially at either temperature. Indeed, we found that loss of Sh function caused short sleep phenotypes in a temperature-dependent manner. Male flies hemizygous for the mns mutation (Sh[mns]) displayed short and fragmented sleep at 21 °C (Fig. 1b, c and Supplementary Fig. 2), consistent with the previous observations4. Intriguingly, Sh mutants did not display any L sleep phenotypes at 29 °C. Their short D sleep was also partially rescued by high temperature since we detected a significant interaction between temperature and Sh mutation on D sleep amount (Fig. 1c, P < 0.0001 by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). These results thus indicate that Sh promotes sleep more potently at low temperature.

We further investigated if sleep mutant phenotypes in Sh-relevant genes were also sensitive to ambient temperature. As described previously8,9, both Hk and sss mutants showed Sh-like, short sleep phenotypes at 21 °C (Fig. 1b, c and Supplementary Fig. 2). However, these two sleep mutants behaved very differently at 29 °C. Loss of Hk function largely phenocopied Sh mutation, since short sleep in Hk mutants was significantly rescued at 29 °C (P < 0.0001 for temperature x genotype interaction on either L or D sleep by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). By contrast, sss mutants showed short L sleep even at 29 °C and additive effects of temperature and sss mutation were detected on L sleep (P = 0.6722 for sss[MI] heterozygous backgrounds by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). Given the lack of Sh phenotypes in L sleep at 29 °C, these observations suggest that sss promotes L sleep independently of its regulatory role in Sh function at high temperature. In this regard, transgenic expression of wild-type sss in cholinergic neurons of sss mutants rescued short sleep but not leg-shaking phenotypes relevant to Sh6. It has been further demonstrated that sss antagonizes nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and suppresses cholinergic transmission in wake-promoting neurons10.

Light masks Sh effects on sleep at high temperature

High temperature suppresses D sleep consolidation, which may lead to the lengthening of L sleep duration as a consequence of sleep homeostasis32,33. We reasoned that a similar mechanism could underlie temperature-sensitive L sleep phenotypes in Sh mutants. Accordingly, we compared wild-type and Sh mutant sleep in constant light (LL) or constant dark (DD). LL abolishes circadian rhythms in Drosophila34, thus disrupting daily sleep-wake cycles. Conversely, DD allows circadian gene expression and locomotor rhythms in the free-running condition while avoiding any direct behavioral responses to light transitions.

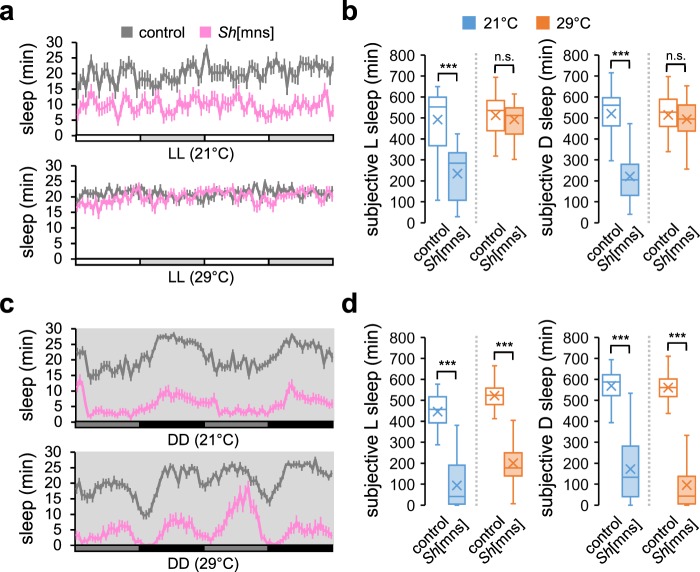

Sh mutants displayed short sleep phenotypes in LL at 21 °C (Fig. 2a, b), indicating that sleep-promoting effects of Sh require neither circadian clocks nor daily light cycles. By contrast, Sh mutant phenotypes disappeared in LL at 29 °C, consistent with the lack of Sh effects on L sleep in LD cycles at high temperature. Further sleep analyses revealed that Sh mutants showed short DD sleep at either temperature (Fig. 2c, d) and no significant interactions between temperature and Sh mutation were detected on DD sleep (P = 0.1002 for subjective L; P = 0.0918 for subjective D by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). These observations could be explained by a model that Sh promotes sleep at either temperature but light masks Sh effects more strongly at high temperature. In either constant condition, high temperature suppressed Hk mutant sleep (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b) whereas ambient temperature did not significantly affect sss mutant sleep (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). Although sleep behaviors are likely governed by more complex mechanisms in LD cycles, our results demonstrate that light and temperature cooperatively gate the sleep-promoting effects of Sh in a manner independent of circadian rhythms or sleep homeostasis. The interplay between light and temperature has also been documented on heat-induced sleep in circadian clock mutants31.

Fig. 2. Light masks Sh effects on sleep at high temperature.

Sleep behaviors in individual male flies were analyzed in constant light (LL) or constant dark (DD) at 21 °C or 29 °C. a, c Sleep profiles of control (gray lines) or Sh mutants (pink lines) during the first two cycles of LL or DD. Data represent average ± SEM (n = 20–48). b, d Box plots represent the total amounts of subjective L or subjective D sleep on the second cycle of LL or DD at 21 °C (blue boxes) or 29 °C (orange boxes) (n = 20–48). Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA detected significant interactions between Sh mutation and temperature on sleep duration in LL (P < 0.0001 for either subjective L or subjective D), but not in DD (P = 0.1002 for subjective L; P = 0.0918 for subjective D). n.s., not significant; ***P < 0.001 as determined by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Sh depletion in GABAergic neurons phenocopies Sh mutants

Sh mutation leads to the hyperexcitability of affected neurons, delaying repolarization by potassium efflux and possibly elevating intracellular Ca2+ levels35,36. Given the genetic evidence that Sh promotes sleep, a simple hypothesis would be that loss of Sh function in wake-promoting neurons excites their neural activity and thereby suppresses sleep. In fact, a previous study has shown that RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated depletion of the SH complex, including HK and SSS, in sleep-promoting dFSB neurons suppresses sleep21. This puzzling observation indicates a more elaborate mechanism for Sh function in dFSB neurons that sustains their tonic firing during sleep25. Nonetheless, it does not exclude the possibility that Sh may also act in brain regions other than dFSB neurons6, contributing to temperature-sensitive L sleep in Sh mutants. Accordingly, we employed a similar RNAi strategy to deplete Sh expression in a specific group of neurons and examined its effects on sleep behaviors.

We first confirmed that overexpression of the Sh RNAi transgene by the pan-neuronal galactose-responsive transcription factor 4 driver (ELAV-Gal4) reduced Sh transcript levels in adult fly heads (Supplementary Fig. 4). The pan-neuronal silencing of Sh expression indeed suppressed sleep only at 21 °C, partially phenocopying Sh mutant sleep (Fig. 3a, b). Similarly, pan-neuronal disruption of the Sh locus by CRISPR-mediated targeting37 suppressed sleep at 21 °C, but not at 29 °C (Supplementary Fig. 5). The stronger transgenic phenotypes at low temperature cannot be explained by the intrinsic temperature dependency of the Gal4 activity since high temperature actually enhances the Gal4-driven expression of Drosophila transgenes in general. These results further support that loss of neuronal Sh function, but not the temperature-sensitive nature of the Sh[mns] allele, may underpin temperature-sensitive sleep phenotypes in Sh mutants.

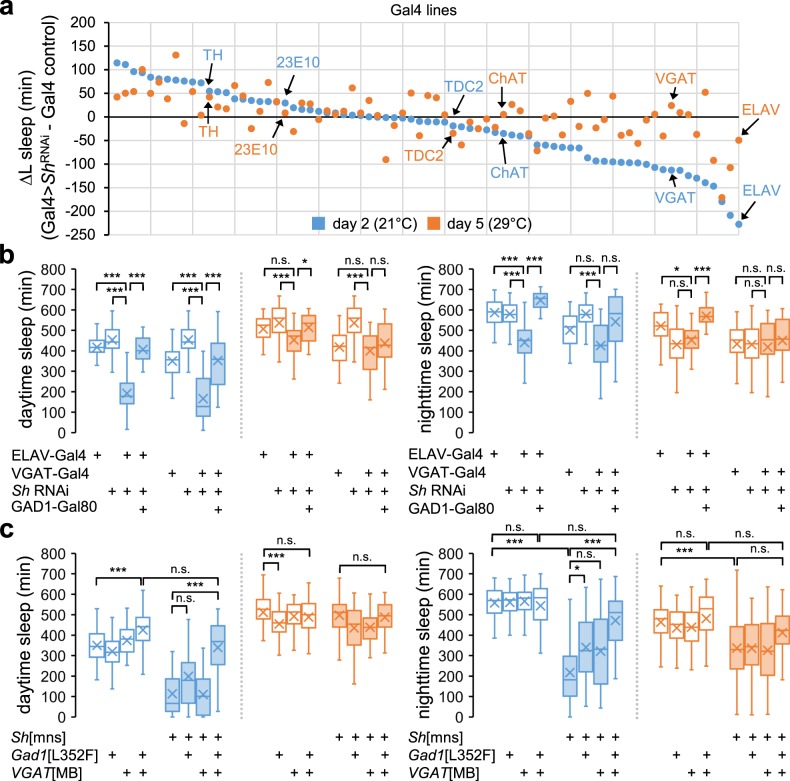

Fig. 3. Sh acts in GABAergic neurons to promote sleep likely via GABA transmission.

a A series of Gal4 drivers was genetically combined with Sh RNAi transgene (Sh RNAi#1, BL53347) to deplete endogenous Sh expression in distinct sets of cells. Sleep behaviors were analyzed individually in transgenic male flies. The differences in the averaged amount of L sleep between Gal4>ShRNAi and Gal4 control flies (∆L sleep, n = 15–91) for each Gal4 driver were plotted by blue (day 2, 21 °C) or orange dots (day 5, 29 °C), respectively. The x-axis indicates each Gal4 line sorted by the size of ∆L sleep at 21 °C. b Box plots represent the total amounts of L or D sleep on day 2 (21 °C, blue boxes) versus day 5 (29 °C, orange boxes) (n = 24–62). The Sh RNAi#1 transgene was co-expressed with Dicer-2 to enhance RNAi effects. Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA detected significant interactions of temperature with Sh depletion in all neurons (ELAV-Gal4) or GABAergic neurons (VGAT-Gal4 (II), BL58980) on L sleep (P < 0.0001). n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 as determined by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. c Trans-heterozygous mutations in GAD1 and VGAT suppress temperature-sensitive plasticity of wild-type and Sh mutant sleep (n = 25–122). n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 as determined by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA, Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

We then tested a number of Gal4 drivers to deplete Sh expression in individual subsets of neurons (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 1). Sh depletion in wake-promoting neurons that release DA (TH-Gal4), OA (TDC2-Gal4), or acetylcholine (ChAT-Gal4)38 negligibly affected sleep (Supplementary Fig. 6). We also did not detect any sleep suppression by Sh depletion in dFSB neurons (23E10-Gal4) (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7), possibly due to some differences in experimental conditions (e.g., temperature, gender, age). On the other hand, we found that two Gal4 drivers (i.e., 121y-Gal4 and 30y-Gal4) expressed broadly in adult brain, including the mushroom body, significantly suppressed L sleep at either temperature while causing short D sleep only at 21 °C (Supplementary Fig. 8). Accordingly, these data suggest that a sub-group of Sh-expressing neurons may suppress sleep regardless of ambient temperature. We also reason that sleep phenotypes observed in Sh mutants are caused by the net effects of its loss-of-function in various subtypes of Sh-expressing neurons (e.g., wake-promoting vs. sleep-promoting, constitutive vs. thermosensitive).

Our genetic screen further identified a vesicular γ-aminobutyric acid transporter (VGAT)-Gal4 driver as one of the strongest hits that mimicked L sleep phenotypes in Sh mutants (Fig. 3a, b). Sh depletion in VGAT-expressing neurons suppressed L sleep at 21 °C, but not at 29 °C, whereas it did not cause any D sleep phenotypes at either temperature. Similar results were obtained using independent transgenic lines of VGAT-Gal4 or Sh RNAi (Supplementary Fig. 9), excluding their off-target effects. The lack of D sleep phenotypes by VGAT-Gal4 may indicate that VGAT-expressing neurons contribute specifically to short L sleep in Sh mutants. Alternatively, the degree of Sh depletion by VGAT-Gal4 may not be sufficient to suppress D sleep. VGAT-Gal4 contains a transgenic promoter from the VGAT locus and is expressed in neurons that release the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA39. To validate if Sh expression in GABAergic neurons was responsible for Sh mutant sleep, we genetically combined a glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 (GAD1)-Gal80 repressor transgene40 with the pan-neuronal driver (ELAV-Gal4) or VGAT-Gal4 to overexpress the Sh RNAi transgene. Since GAD1 is a key enzyme for GABA synthesis, this genetic manipulation would block the RNAi-mediated depletion of Sh selectively in GABAergic neurons. Indeed, GAD1-Gal80 rescued the sleep phenotypes caused by the RNAi-mediated depletion of Sh (Fig. 3b). These data strongly implicate GABAergic neurons as a neural locus important for temperature-sensitive effects of Sh on sleep behaviors, although we do not rule out the possibility that VGAT-Gal4 or GAD1-Gal80 transgene may also be expressed in some non-GABAergic cells.

Inhibition of GABA transmission suppresses Sh mutant sleep

To validate Sh-dependent neural activity in GABAergic neuron, we expressed a Ca2+-sensitive transcriptional fluorescence reporter CaLexA41 in VGAT-expressing neurons. Their fluorescence signals were then compared between wild-type or Sh mutant flies entrained at either 21 °C or 29 °C. Similar approaches have been employed in previous studies to measure long-term changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels as a proxy for neural activity22,42,43. The quantification of our Ca2+ imaging revealed that Sh mutation elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels in subsets of VGAT-expressing neurons (Supplementary Fig. 10). This was consistent with previous observations that loss of Sh function increases neuronal excitability35,36. Significant effects of Sh on Ca2+ levels were detected in mushroom body and ellipsoid body (Supplementary Fig. 10b, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0165, respectively, by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). We further detected statistically significant interaction between Sh mutation and temperature on Ca2+ levels in mushroom body (P = 0.0148 by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA), but not in ellipsoid body (P = 0.2180 by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). In fact, high temperature generally weakened the CaLexA-driven fluorescence signals in either wild-type or Sh mutant brains (Supplementary Fig. 10b, P < 0.0001 for mushroom body and antenna lobe; P < 0.001 for ellipsoid body and pars intercerebralis by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). This observation possibly points to the intrinsic temperature-sensitivity of the CaLexA transgene. Nonetheless, these data support that Sh mutation likely increases the excitability of GABAergic neurons and thereby sustains GABA transmission.

If greater neural activity in GABAergic neurons was responsible for Sh mutant sleep, we reasoned that a down-scaling of the presynaptic GABA transmission should suppress Sh mutant phenotypes. To this end, we genetically silenced GABA transmission by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in VGAT, which incorporates GABA into the synaptic vesicles of GABAergic neurons39,44, or in GABA-synthesizing GAD145. Their effects on sleep behaviors were then compared between wild-type and Sh mutant backgrounds. The heterozygosity of either VGAT or GAD1 had negligible effects on wild-type sleep at either 21 °C or 29 °C (Fig. 3c). However, their trans-heterozygosity increased the amount of wild-type L sleep specifically at 21 °C (Fig. 3c, P < 0.0001 for temperature x genotype interaction on L sleep by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA), thereby dampening temperature-dependent changes in L sleep duration. More importantly, the trans-heterozygosity of VGAT and GAD1 rescued Sh mutant sleep at 21 °C (Fig. 3c, P < 0.0001 for trans-heterozygosity of VGAT and GAD1 × Sh[mns] interaction on either L or D sleep by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA) while it had additive effects with Sh mutation on D sleep at 29 °C (P > 0.05 for trans-heterozygosity of VGAT and GAD1 × Sh[mns] interaction on D sleep by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). The heterozygosity of VGAT similarly suppressed L sleep phenotypes caused by Sh depletion in VGAT-expressing neurons (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Collectively, these genetic interaction data provide convincing evidence that a GABA-dependent mechanism contributes to temperature-dependent effects of Sh on sleep behaviors.

Rdl in dFSB neurons acts downstream of Sh to suppress sleep

GABA receptor agonists potently enhance sleep in both flies and mammals11,12,46. By contrast, we observed that genetic suppression of GABA transmission actually promoted L sleep at 21 °C in wild-types and rescued short sleep phenotypes in Sh mutants. GABA receptor genes are broadly expressed in the adult fly brain47,48. Several lines of evidence indicate that the sleep-modulatory effects of each GABA receptor are mediated by a specific group of neurons involved in the regulation of sleep-wake cycles12–16. Given the inhibitory nature of GABA transmission onto postsynaptic neurons, we reasoned that GABA receptors may act in sleep-promoting neurons to mediate Sh mutant phenotypes. To elucidate this sleep-suppressing role of GABA transmission, we depleted endogenous expression of individual GABA receptors in different groups of sleep-regulatory neurons and examined their effects on sleep behaviors.

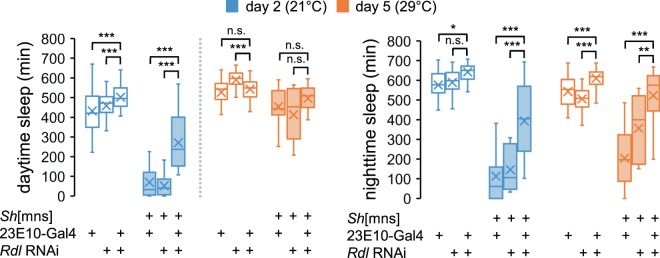

The most striking effects were observed when we silenced the expression of the ionotropic GABA receptor, Resistant to dieldrin (Rdl), in sleep-promoting dFSB neurons49. While Rdl expression in dFSB neurons has been reported previously50–52, we found that dFSB-specific Rdl depletion lengthened wild-type L sleep at 21 °C, but not at 29 °C (Fig. 4). These sleep phenotypes were in stark contrast to Sh mutant sleep (Fig. 1b, c), suggesting the opposing effects of presynaptic Sh in GABAergic neurons and postsynaptic Rdl in dFSB neurons on sleep behaviors. Indeed, Rdl depletion in dFSB neurons non-additively suppressed Sh mutant sleep only at 21 °C (Fig. 4, P < 0.001 or P < 0.01 for Rdl depletion × Sh[mns] interaction on L or D sleep, respectively, by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). These results support that Rdl in dFSB neurons acts genetically downstream of GABAergic Sh and antagonizes its effects on sleep at low temperature. Accordingly, Sh effects on sleep likely converge on a specific group of sleep-promoting neurons despite our mapping of the Sh RNAi phenotypes broadly to GABAergic neurons (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 4. Ionotropic GABA receptor Rdl in dFSB neurons acts downstream of Sh to suppress sleep.

23E10-Gal4 driver was genetically combined with Rdl RNAi transgene to deplete endogenous Rdl expression in dFSB neurons of wild-type or Sh mutant flies. Sleep behaviors were analyzed individually in transgenic male flies. Box plots represent the total amounts of L or D sleep on day 2 (21 °C, blue boxes) versus day 5 (29 °C, orange boxes) (n = 20–63). Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA detected significant interactions of Rdl depletion in dFSB neurons with Sh on sleep duration at 21 °C (P < 0.001 for L sleep; P < 0.01 for D sleep), but not at 29 °C. n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as determined by Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

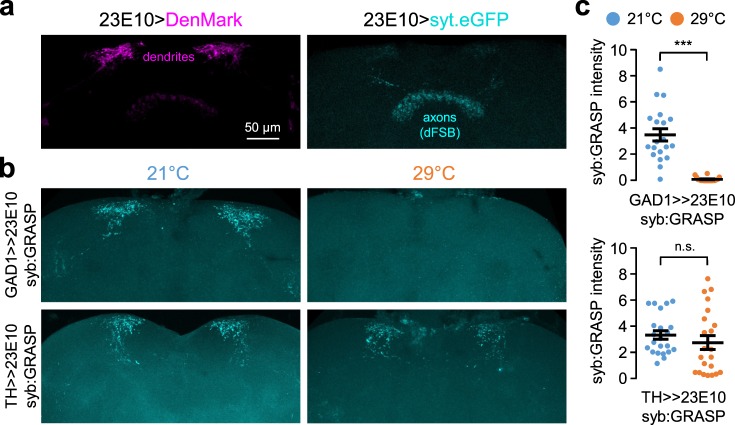

GABAergic synapses onto dFSB display temperature-sensitivity

To functionally validate GABAergic synapses onto dFSB neurons, we examined synaptic GFP reconstitution across synaptic partners (GRASP) between GAD1-expressing neurons and dFSB neurons. Unlike the original GRASP53,54, synaptobrevin-GRASP (syb:GRASP) requires the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic membrane to display trans-synaptic fluorescence at the synaptic cleft55. Accordingly, the presence of the syb:GRASP signals verifies the directionality of a given synapse between two groups of neurons. In addition, the relative intensity of their fluorescence is proportional to the neural activity of presynaptic neurons. With this experimental design, we detected the syb:GRASP signals enriched in the dendritic regions of dFSB neurons56–59 (Fig. 5a, b), validating the directionality of functional synapses from GAD1-expressing neurons to dFSB neurons. Quantitative image analyses further revealed that the syb:GRASP signals from GAD1-expressing neurons were more evident in flies that had been entrained in LD cycles at 21 °C than in those entrained at 29 °C (Fig. 5c, P < 0.0001 by Mann–Whitney U test). These data suggest that GABAergic neurons display higher synaptic transmission onto dFSB neurons at low temperature.

Fig. 5. GABAergic synapses, but not dopaminergic synapses, onto dFSB neurons display temperature-sensitive activity.

a Dendrites and axonal projections from dFSB neurons were visualized by transgenic expression of the fluorescent marker proteins DenMark (magenta) and syt.eGFP (cyan), respectively (23E10-Gal4/UAS-DenMark, UAS-syt.eGFP). Weak DenMark signals in the dFSB region may indicate leaky expression in non-dendritic regions80. Alternatively, a minor population of dFSB neurons may have dendrites in the dFSB region. b Transgenic flies were pre-entrained in LD cycles at 21 °C (blue) or 29 °C (orange), and their whole brains were dissected out. The fluorescence images of whole-mount brains were obtained using a multi-photon microscopy. Representative z-stack images of the synaptic GRASP (syb:GRASP) signals from GABAergic (lexAop-nSyb-spGFP1-10, UAS-CD4-spGFP11/+; GAD1-LexA/23E10-Gal4) or dopaminergic neurons (lexAop-nSyb-spGFP1-10, UAS-CD4-spGFP11/+; TH-LexA/23E10-Gal4) to dFSB neurons were shown. c The fluorescence intensity of the syb:GRASP at the dendritic regions of dFSB neurons was quantified using ImageJ software. Fluorescence signals above a threshold level (i.e., background) were integrated from each hemisphere, and averaged per genotype at each temperature (n = 18–22 hemispheres). Data represent average ± SEM. n.s., not significant; ***P < 0.001 as determined by Mann–Whitney U test.

Since dFSB neurons also receive inhibitory dopaminergic inputs18,19,21, we examined whether ambient temperature also affected dopaminergic synapses onto dFSB neurons. In contrast to GABAergic synapses, the syb:GRASP signals from dopaminergic neurons were comparable between two groups of flies that had been entrained at either 21 °C or 29 °C, respectively (Fig. 5c, P = 0.1777 by Mann–Whitney U test). Taken together, our results indicate that high temperature specifically weakens GABAergic synapses onto dFSB neurons. We reason that this temperature-dependent neural plasticity likely explains stronger sleep phenotypes in Sh mutants or Sh-depleted flies at low temperature.

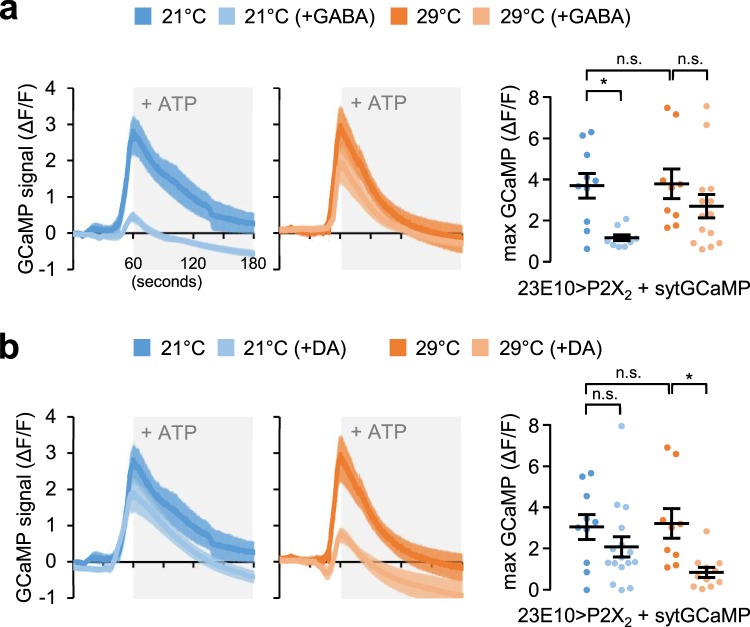

GABA and DA differentially reduce dFSB excitability

DA transmission down-regulates the excitability of dFSB neurons, switches them to an electrically quiescent status, and suppress sleep21. On the other hand, our data indicate that GABAergic synapse onto dFSB neurons displays temperature-sensitive activity (Fig. 5) and supports temperature-dependent plasticity of wild-type and Sh mutant sleep (Figs. 3c and 4b). Given the inhibitory nature of GABA transmission to postsynaptic neurons, we asked if the excitability of dFSB neurons is differentially modulated by GABA and DA. To this end, we expressed an ATP-gated cation channel P2X2 along with a synaptic calcium sensor sytGCaMP in dFSB neurons. The transgenic combination allowed us to cell-autonomously excite dFSB neurons by ATP application and measure their excitability using fluorescent Ca2+ imaging in live brains60. We first found that ATP-induced elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels in dFSB neurons were comparable between transgenic flies entrained at 21 °C and 29 °C (Fig. 6). However, pre-incubation of either GABA or DA suppressed the excitability of dFSB neurons in a temperature-sensitive manner. In particular, GABA potently suppressed the excitability of dFSB neurons only at 21 °C (Fig. 6a) whereas DA silenced it only at 29 °C (Fig. 6b). These results indicate that inhibitory effects of GABA and DA on dFSB neurons are differentially gated by temperature. Considering our GRASP data, we reasoned that temperature might modify the neural property of postsynaptic dFSB neurons, thereby governing their excitability via temperature-specific neurotransmitter signaling.

Fig. 6. GABA and DA suppress the excitability of dFSB neurons in a temperature-sensitive manner.

An ATP-gated cation channel P2X2 was expressed in dFSB neurons along with a synaptic calcium sensor sytGCaMP (23E10 > P2X2, sytGCaMP) to quantify ATP-induced changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels as an indirect readout of the neural excitability. Transgenic flies were pre-entrained in LD cycles at 21 °C (blue) or 29 °C (orange). Whole brains were dissected out, transferred to an imaging chamber, and equilibrated with HL3 buffer for 5 minutes. Where indicated, dissected brains were incubated with 50 mM GABA (a) or 10 mM DA (b) for 5 minutes prior to the batch application of 5 mM ATP (shaded by gray boxes). A time series of the fluorescence images was recorded using a photoactivated localization microscopy and their quantification was performed using ZEN software. Data represent average ± SEM (n = 9–14). n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05 as determined by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA, Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

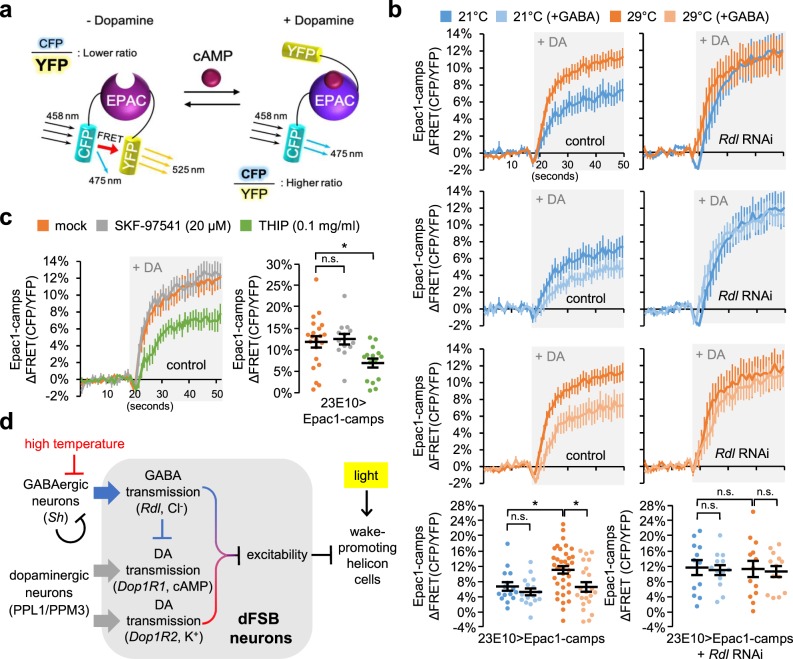

GABA transmission suppresses DA signaling in dFSB neurons

To determine if ionotropic GABA transmission in postsynaptic dFSB neurons is affected by temperature, we examined GABA-dependent changes in intracellular chloride levels using a transgenic fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensor SuperClomeleon14,61. Bath application of GABA robustly elevated chloride levels in dFSB neurons, but their FRET responses were comparable at 21 °C and 29 °C (Supplementary Fig. 11). It is thus unlikely that chloride influx via ionotropic GABA receptors is limiting at 29 °C to explain lack of GABA effects on the excitability of dFSB neurons at high temperature. We further quantified postsynaptic DA signaling in dFSB neurons using Epac1-camps, another transgenic FRET sensor for cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)62 (Fig. 7a). cAMP is a signaling molecule downstream of D1-like DA receptors implicated in Drosophila sleep18,19,21. Live-brain imaging of the transgenic Epac1-camps, expressed in dFSB neurons, allowed us to measure the relative changes in intracellular cAMP levels by bath application of DA19.

Fig. 7. Ionotropic GABA transmission suppresses postsynaptic DA signaling in dFSB neurons and supports temperature-sensitive DA transmission.

a DA receptor signaling elevates intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels. The subsequent binding of cAMP to Epac1-camps (EPAC) induces conformational change in the FRET sensor, thereby increasing the fluorescence ratio of CFP to YFP. b Epac1-camps was expressed in dFSB neurons of control (23E10 > Epac1-camps) or Rdl RNAi flies (23E10 > Epac1-camps + Rdl RNAi). Transgenic flies were pre-entrained in LD cycles at 21 °C (blue) or 29 °C (orange). Whole brains were dissected out and transferred to an imaging chamber. Where indicated, dissected brains were pre-incubated with 1 mM GABA for 5 min prior to the induction of FRET responses by the batch application of 10 mM DA (shaded by gray boxes). A time series of the fluorescence images was recorded using a multi-photon microscopy and their FRET analysis was performed using ZEN software. Data represent average ± SEM (n = 15–37 for 23E10 > Epac1-camps; n = 12–13 for 23E10 > Epac1-camps + Rdl RNAi). Two-way ANOVA detected significant effects of either temperature or GABA on the DA-induced FRET response in control (P = 0.0238 or P = 0.0151, respectively), but not in Rdl-depleted dFSB neurons (P = 0.7894 or P = 0.7040, respectively). n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05 as determined by Tukey post hoc test. c 23E10 > Epac1-camps flies were pre-entrained in LD cycles at 29 °C. Where indicated, dissected brains were pre-incubated with SKF-97541 (20 µM, a metabotropic GABA receptor agonist) or THIP (0.1 mg/ml, an ionotropic GABA receptor agonist) for 5 min prior to the induction of FRET responses by the batch application of 10 mM DA. Data represent averag ± SEM (n = 13–21). n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05 as determined by one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test. d A model for the genetic and neural interplay of sleep-promoting dFSB neurons that supports temperature- and light-sensitive plasticity of sleep behaviors.

Interestingly, we observed that DA-induced cAMP elevation was more robust in dFSB neurons of transgenic flies entrained at 29 °C than those entrained at 21 °C (Fig. 7b). While these observations were consistent with temperature-sensitive effects of DA on the excitability of dFSB neurons, we reasoned that higher activity of GABAergic synapses at 21 °C might have a negative impact on DA signaling in dFSB neurons. Indeed, dFSB-specific depletion of Rdl reversed the repression of the intracellular cAMP response to DA at 21 °C, thus blunting its temperature-dependency (Fig. 7b). Moreover, pre-incubation with GABA repressed DA-induced cAMP elevation in dFSB neurons of control flies, while the transgenic depletion of Rdl masked GABA effects. The weaker suppression by exogenous GABA at 21 °C likely reflected a floor effect caused by the stronger transmission of endogenous GABA to dFSB neurons at low temperature. Finally, we observed that an agonist of ionotropic GABA receptors (THIP), but not that of metabotropic GABA receptors (SKF-97541), suppressed DA-induced cAMP elevation (Fig. 7c), consistent with the Rdl RNAi effects. Collectively, our data demonstrate that ambient temperature tunes the postsynaptic signaling of DA transmission to dFSB neurons via temperature-sensitive GABA synapses. This neural mechanism may confer temperature-dependent plasticity on the sleep-regulatory function of dFSB neurons.

Discussion

High ambient temperature promotes sleep during the daytime but suppresses sleep consolidation at night, thereby inducing greater nocturnal activity in diurnal animals27,29. The temperature-dependent remodeling of sleep-wake patterns represents a behavioral adaptation to the environment, which is considered beneficial for animal fitness and is likely conserved across species, including humans63,64. Nonetheless, the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are poorly documented. Our genetic studies in Drosophila demonstrated that ionotropic GABA transmission from Sh-expressing neurons to sleep-promoting dFSB neurons constitutes as a neural pathway responsible for temperature-dependent control of sleep behaviors. The opposing effects of presynaptic Sh and postsynaptic GABA receptor Rdl may buffer drastic fluctuations in sleep duration over a range of ambient temperatures, thereby underscoring temperature-relevant sleep homeostasis. In addition, the temperature-sensitive activity of the GABA synapse plays important roles in adjusting postsynaptic DA signaling in dFSB neurons, thereby modulating their neural property in a temperature-dependent manner. Finally, light-dependent masking overrides the sleep-regulatory output from this Sh-relevant pathway particularly at high temperature, explaining siestas on hot days. These findings uncover an important neural principle by which environmental changes are translated into synaptic plasticity of a specific neural locus with sleep-regulatory function, possibly leading to adaptive behavioral plasticity (Fig. 7d).

Previous studies have suggested that circadian clock genes (e.g., period and cryptochrome) and a group of circadian pacemaker neurons (e.g., posterior dorsal DN1p neurons) contribute to the immediate modification of sleep behaviors by elevated temperatures30,31. Our data indicate that temperature-adaptive sleep plasticity is manifested gradually in various sleep parameters after temperature shift (Supplementary Fig. 1). We reason that a chronic shift to high temperature implicates neural plasticity (e.g., the adjustment of temperature-sensitive synapses) that stabilizes temperature-adaptive sleep behaviors. The transient effects of clock gene mutations on temperature-dependent sleep behaviors31, as well as the gender-specific delay in the latency to L sleep onset by high temperature30, further support the idea that the molecular and neural mechanisms underlying the immediate behavioral responses to temperature shifts are likely distinguishable from those triggering long-term changes in sleep architecture.

A physiological range of environmental temperatures is sensed by dedicated groups of neurons that express distinct thermo-sensing molecules and are associated with specific behavioral responses (e.g., temperature preference or avoidance)65. This raises the possibility that Sh-expressing neurons are an intrinsic component for neural sensing or processing of ambient temperatures. Alternatively, but not exclusively, SH channel activity itself may be thermosensitive as observed in transient receptor potential (TRP) channels66, thereby modulating its sleep-promoting effects in a temperature-dependent manner. However, SH activity seems to remain constant over a physiological range of temperatures, although genetic uncoupling of its voltage sensor from the gating mechanism can alter its temperature sensitivity67. In fact, we observed that a loss-of-function mutation in the thermosensitive channel TrpA1 or the surgical ablation of antenna (a peripheral tissue for temperature sensing in Drosophila)65 blunted the temperature effects on L sleep in wild-type flies (Supplementary Fig. 12, P < 0.0001 for temperature × TrpA1 mutation interaction; P < 0.001 for temperature x antenna ablation interaction on L sleep by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). This was also consistent with the previously reported role of TrpA1 in temperature-dependent control of morning wakefulness30. Nonetheless, Sh mutants displayed temperature-sensitive sleep phenotypes even in the absence of TrpA1 (Supplementary Fig. 12, P < 0.0001 for temperature × Sh mutation interaction on either L or D sleep in TrpA1 mutant backgrounds by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA). These results suggest that TrpA1-dependent sensing of warm temperature may contribute to the behavioral plasticity of sleep in wild-types, whereas the Sh-relevant neural pathway likely acts independent or downstream of TrpA1.

dFSB neurons have been mapped as a postsynaptic locus that expresses Drosophila homologs of D1-like DA receptors and is responsible for DA-dependent arousal18,19,21. Genetic or pharmacological enhancement of DA transmission suppresses sleep via Dop1R1-mediated cAMP/PKA signaling in dFSB neurons18,19. Prolonged DA transmission switches dFSB neurons to electrically quiescent neurons21. This transformation is transduced by Dop1R2 and involves neural manipulation of two types of potassium currents manifested by the voltage-gated Sh and the leak channel Sandman, respectively21. Nonetheless, we identified presynaptic GABAergic neurons expressing Sh and postsynaptic dFSB neurons expressing Rdl as the thermosensitive neural pathway important for gating the postsynaptic DA transmission in dFSB neurons as well as reorganizing sleep behaviors according to ambient temperature.

Previous studies in mammals have actually made several observations relevant to our findings. The inhibitory synapse from a group of wake-promoting GABAergic neurons in lateral hypothalamus to the VLPO, one of the mammalian sleep-promoting nuclei analogous to dFSB neurons, likely acts as a sleep-wake switch68. Cross-talks between GABA and DA transmission have also been demonstrated at the level of postsynaptic receptor signaling69. For example, ionotropic GABA receptors directly associate with hippocampal D5 receptors; this suppresses DA-induced cAMP levels and GABA currents70. In addition, D1 receptor activation leads to PKA-dependent phosphorylation of ionotropic GABA receptors and their subsequent internalization71–73. Given the latter observation, we speculate that GABAergic inhibition of DA receptor signaling in dFSB neurons provides a neural mechanism ensuring robust switching between these two postsynaptic pathways upon temperature shifts. More specifically, at 21 °C, GABA may strengthen its own transmission by inhibiting DA receptor signaling. Weaker GABA transmission at 29 °C would reverse the repression of DA transmission, which in turn would suppress any residual GABA receptor activity. This model explains temperature-sensitive dominance of GABA or DA in silencing the excitability of dFSB neurons (Fig. 6). Nonetheless, we found that chloride influx induced by exogenous GABA was not limiting in dFSB neurons at 29 °C (Supplementary Fig. 11), suggesting the presence of additional postsynaptic mechanisms that might suppress GABA effects on the dFSB excitability at high temperature.

dFSB neurons suppress wake-promoting helicon cells via the neuropeptide allatostatin-A signaling24. This neural pathway constitutes an auto-regulatory circuit that comprises dFSB neurons, helicon cells, and R2 ring neurons of the ellipsoid body (R2 EB)22,23,57 and establishes a neural basis of sleep homeostasis in Drosophila3,74,75. Intriguingly, light excites helicon cells24 and thus we reason that low baseline activity of helicon cells in the absence of light may cause a floor effect, desensitizing them to the inhibitory signals from dFSB neurons (Fig. 7d). Under these conditions, Sh mutant sleep would be contributed by other neural pathways. The presence of light, on the other hand, may increase the baseline activity of helicon cells that can be further scaled by opposing effects of the inhibitory signals from dFSB neurons, and of temperature-sensitive GABAergic synapse onto dFSB neurons. This model explains light-dependent masking of Sh mutant phenotypes at 29 °C since high temperature will silence wake-promoting effects of Sh mutation in GABAergic neurons on dFSB neurons. Future studies should further elaborate on principles underlying the complex interaction of temperature with different light regime on Sh mutant sleep.

In conclusion, plasticity in sleep behaviors represents an important strategy for sustaining animal physiology in response to external or internal changes in the sleep environment. Our study establishes a genetic pathway that constitutes temperature-sensitive GABA transmission to the sleep-promoting neural locus and generates neural plasticity underpinning the adaptive organization of sleep architecture. Given the similarities of temperature-dependent sleep behaviors between flies and humans, we propose that this underlying neural strategy may be conserved across species.

Methods

Fly stocks

All flies were maintained in standard cornmeal–yeast–agar medium at 25 °C. w[1118] (BL5905; wild-type control), Sh[mns] (BL24149), Sh[TKO] (BL76968), sss[P1] (BL16588), sss[MIC] (BL34309), Gad1[L352F] (BL6295), VGAT[MB01219] (BL23022), TrpA1[1] (BL26504), UAS-Sh RNAi #1 (BL53347), UAS-Rdl RNAi (BL52903), ELAV-Gal4 (BL458), ELAV-Gal4; UAS-Cas9 (BL67073), VGAT-Gal4 (II) (BL58980), VGAT-Gal4 (III) (BL58409), 23E10-Gal4 (BL49032), TH-Gal4 (BL8848), TDC2-Gal4 (BL9313), ChAT-Gal4 (BL6798), 121y-Gal4 (BL30815), 30y-Gal4 (BL30818), GAD1-LexA (BL60324), UAS-mLexA-VP16-NFAT (BL66542; CaLexA), UAS-DenMark, UAS-syt.eGFP (BL33065), lexAop-nSyb-spGFP1-10, UAS-CD4-spGFP11 (BL64315; syb:GRASP), UAS-SuperClomeleon (BL59847), and UAS-Epac1-camps (BL25407) were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Hk[1] (101-119) was obtained from Kyoto Stock Center. UAS-Sh RNAi #2 (v104474) was obtained from Vienna Drosophila Resource Center. GAD1-Gal80, TH-LexA, and UAS-sytGCaMP6s; UAS-P2X2 were gifts from Y. Li (Chinese Academy of Sciences), H. Tanimoto (Tohoku University), and R. Allada (Northwestern University), respectively.

Behavioral analysis

To avoid possible effects of undefined genetic backgrounds on sleep behaviors, all mutants and transgenic flies were tested in outcrossed conditions. Sleep behaviors in experimental genotypes were compared to those in control genotypes obtained from appropriate genetic crosses in parallel. w[1118] was set as a wild-type in all genetic crosses to generate control flies heterozygous for mutant alleles or transgenes (e.g., Gal4, Gal80, UAS). Hemizygous male mutants (e.g., Sh[mns], Hk[1]) were generated by crossing mutant virgins to w[1118] males whereas their genetic controls were obtained from parallel crosses in reverse orientation. Sleep behaviors in experimental flies with a specific combination of mutant alleles or transgenes were compared to those in control flies heterozygous for individual ones. Each male fly was transferred into a 65 × 5 mm glass tube containing 5% sucrose and 2% agar food. Locomotor activity in individual flies was then recorded using the Drosophila Activity Monitor system (Trikinetics) and quantified by the number of infrared beam crosses per minute. Behavioral data were collected from more than two independent tests and averaged per genotype. For LD sleep analysis, flies were entrained for 3 days in LD cycle at 21 °C prior to the temperature shift to 29 °C at ZT16 (lights-on at ZT0; lights-off at ZT12) in the last LD cycle at 21 °C. They were further incubated for 3 days in LD cycle at 29 °C. For LL or DD sleep analysis, flies were kept in constant conditions at 21 °C or 29 °C. A sleep bout was defined as a behavioral episode during which flies did not show any activity for 5 min or longer. Sleep parameters were accordingly analyzed with an Excel macro76.

Whole-mount brain imaging

Transgenic flies were entrained in LD cycles at either 21 °C or 29 °C for a week. Whole brains were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in PBS containing 3.7% formaldehyde for 28 minutes at room temperature (RT), and then washed three times in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-T). For immunostaining, fixed brains were blocked in PBS-T containing 0.5% normal goat serum for 30 min at RT and then incubated with mouse anti-GFP antibody (diluted in PBS-T containing 0.5% NGS and 0.05% sodium azide at 1:1000, NeuroMab) for 2 days at 4 °C. After washing with PBS-T, brains were further incubated with anti-mouse Alexa Flour 488 antibody (diluted at 1:600, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 day at 4 °C, washed with PBS-T, and then mounted in a VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Fluorescence images were acquired using a multi-photon microscope (LSM780NLO, Carl Zeiss) and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Live-brain imaging

Transgenic flies pre-entrained in LD cycles at either 21 °C or 29 °C for a week were anesthetized in ice. A whole brain was briefly dissected in hemolymph-like HL3 solution (5 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 70 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM trehalose, 115 mM sucrose) and then placed on a cover glass in a magnetic imaging chamber (Chamlide CMB, Live Cell Instrument) filled with HL3 buffer. Live-brain imaging was recorded at room temperature. For GCaMP-based calcium imaging, brains were equilibrated with HL3 buffer for 5 min and then incubated with 50 mM GABA or 10 mM dopamine for 5 min prior to the batch application of 5 mM ATP. A time series of the fluorescence images was recorded using a photoactivated localization microscopy (ELYRA P.1, Carl Zeiss) with a C-Apochromat 40×/1.20 W Korr M27 at a pixel resolution of 512 × 512. Calcium signals were quantified by background substitution method and analyzed using ZEN software (Carl Zeiss). For SuperClomeleon-based FRET imaging, brains were equilibrated with HL3 buffer for 10 minutes prior to the induction of FRET responses by 50 mM GABA. A time series of the fluorescence images was recorded using a multi-photon microscope (LSM780NLO, Carl Zeiss) with a Plan-Apochromat 20×/0.8 at a pixel resolution of 512 × 512. The power of a 458 nm-laser projection was 10%. Two filter ranges (473–491 nm and 509–535 nm) were set for ECFP and EYFP channels, respectively. Pinhole was set as 13.69 AU to select the region of interest within the axon bundle of dFSB neurons. For Epac1-camps-based FRET imaging, brains were incubated with GABA (1 mM), THIP (4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol, 0.1 mg/ml), or SKF-97541 (20 µM) for 5 min prior to the induction of FRET responses by 10 mM DA. A time series of the fluorescence images was recorded using a multi-photon microscope (LSM780NLO, Carl Zeiss) with a Plan-Apochromat 40×/1.3 oil lens at a pixel resolution of 256 × 256. Each stack contained five slices with ~10 µm of step sizes. Pinhole was fully opened (19.07 AU) to avoid any subtle z-drift during imaging acquirement. FRET image analyses were performed using ZEN software (Carl Zeiss).

Quantitative transcript analysis

Fifty fly heads per genotype were homogenized in TRIzol Reagent and total RNAs were extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After DNase I digestion, purified RNAs were reverse-transcribed using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) and random hexamers. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using 2x Prime Q-Mastermix (GeNet Bio) with the diluted cDNA samples and gene-specific sets of primers in LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche). The primer sequences used in this study were as follows: 5’-CCG GTC AAT GTC CCT TTA GA-3’ (forward) and 5’-CTC GAA GAG CAG CCA GAC TT-3’ (reverse) for Sh; 5’-ATC TCC CAC AGG ACG TCA AC-3’ (forward) and 5’-GCG ACG AAG AGA AGG ATC AC-3’ (reverse) for pabp (internal control).

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 or R (version 3.5.3). Datasets that did not pass either Shapiro-Wilk test for normality (P < 0.05) or Brown-Forsythe test for equality of variances (P < 0.05) were analyzed by Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA with ARTool library for multifactorial statistical analyses77,78. Aligned rank transformation (ART) allowed the assessment of temperature or genotype effects on sleep behaviors using non-parametric datasets to validate their significant interaction by ANOVA. Unless otherwise indicated, all sleep parameters were analyzed by repeated measures one-way or two-way ANOVA. For sleep analyses in LL or DD, ordinary two-way ANOVA was conducted. Interaction comparisons were performed using contrast function from the emmeans package (α = 0.05 with the Bonferroni correction)79. Post hoc multiple comparisons were performed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test for repeated measures or by Wilcoxon rank-sum test for unpaired conditions (α = 0.05 with the Bonferroni correction). For statistical analyses of imaging data, significant differences or interactions between experimental conditions were determined by Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA. Where normality or homoscedasticity test was not passed, Mann–Whitney U test or Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA was conducted accordingly. The numbers of samples analyzed per condition and P values obtained from individual statistical analyses were indicated in the main text or figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Guo, Y. Li, H. Tanimoto, R. Allada, Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, Korea Drosophila Resource Center, Kyoto Stock Center, and Vienna Drosophila Resource Center for fly strains. This work was supported by grants from the Suh Kyungbae Foundation (SUHF-17020101); from the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), the Republic of Korea (NRF-2017R1E1A2A02066965; NRF-2018R1A5A1024261; NRF- 2018H1A2A1063084).

Author contributions

C.L. conceived the study; J.K., Y.K., and C.L. designed experiments; J.K., Y.K., M.S.H., and C.L. generated transgenic flies and performed sleep analyses; Y.K., H.L., and J.-H.H. performed imaging experiments; J.K. and Y.K. performed transcript analyses; J.K., B.B., and D.N., and C.L. performed statistical analyses; J.K., Y.K., and C.L. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the paper or available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ji-hyung Kim, Yoonhee Ki.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s42003-020-0902-8.

References

- 1.Allada, R., Cirelli C., & Sehgal A. Molecular mechanisms of sleep homeostasis in flies and mammals. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.9, a027730 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Dubowy C, Sehgal A. Circadian rhythms and sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2017;205:1373–1397. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.185157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomita J, Ban G, Kume K. Genes and neural circuits for sleep of the fruit fly. Neurosci. Res. 2017;118:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cirelli C, et al. Reduced sleep in Drosophila Shaker mutants. Nature. 2005;434:1087–1092. doi: 10.1038/nature03486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JW, Wu CF. In vivo functional role of the Drosophila hyperkinetic beta subunit in gating and inactivation of Shaker K+ channels. Biophys. J. 1996;71:3167–3176. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79510-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu MN, et al. SLEEPLESS, a Ly-6/neurotoxin family member, regulates the levels, localization and activity of Shaker. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:69–75. doi: 10.1038/nn.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean T, Xu R, Joiner W, Sehgal A, Hoshi T. Drosophila QVR/SSS modulates the activation and C-type inactivation kinetics of Shaker K(+) channels. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:11387–11395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0502-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bushey D, Huber R, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Drosophila hyperkinetic mutants have reduced sleep and impaired memory. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:5384–5393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0108-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh K, et al. Identification of SLEEPLESS, a sleep-promoting factor. Science. 2008;321:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1155942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu M, Robinson JE, Joiner WJ. SLEEPLESS is a bifunctional regulator of excitability and cholinergic synaptic transmission. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry JA, Cervantes-Sandoval I, Chakraborty M, Davis RL. Sleep facilitates memory by blocking dopamine neuron-mediated forgetting. Cell. 2015;161:1656–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dissel S, et al. Sleep restores behavioral plasticity to Drosophila mutants. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:1270–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung BY, Kilman VL, Keath JR, Pitman JL, Allada R. The GABA(A) receptor RDL acts in peptidergic PDF neurons to promote sleep in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes, P. R., Christmann, B. L. & Griffith L. C. A single pair of neurons links sleep to memory consolidation in Drosophila melanogaster. Elife4, e03868 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Parisky KM, et al. PDF cells are a GABA-responsive wake-promoting component of the Drosophila sleep circuit. Neuron. 2008;60:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gmeiner F, et al. GABA(B) receptors play an essential role in maintaining sleep during the second half of the night in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:3837–3843. doi: 10.1242/jeb.085563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crocker A, Sehgal A. Octopamine regulates sleep in drosophila through protein kinase A-dependent mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:9377–9385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3072-08a.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Liu S, Kodama L, Driscoll MR, Wu MN. Two dopaminergic neurons signal to the dorsal fan-shaped body to promote wakefulness in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:2114–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueno T, et al. Identification of a dopamine pathway that regulates sleep and arousal in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:1516–1523. doi: 10.1038/nn.3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crocker A, Shahidullah M, Levitan IB, Sehgal A. Identification of a neural circuit that underlies the effects of octopamine on sleep:wake behavior. Neuron. 2010;65:670–681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pimentel D, et al. Operation of a homeostatic sleep switch. Nature. 2016;536:333–337. doi: 10.1038/nature19055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Liu Q, Tabuchi M, Wu MN. Sleep drive is encoded by neural plastic changes in a dedicated circuit. Cell. 2016;165:1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donlea JM, Pimentel D, Miesenbock G. Neuronal machinery of sleep homeostasis in Drosophila. Neuron. 2014;81:860–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donlea JM, et al. Recurrent circuitry for balancing sleep need and sleep. Neuron. 2018;97:378–389 e374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempf A, Song SM, Talbot CB, Miesenbock G. A potassium channel beta-subunit couples mitochondrial electron transport to sleep. Nature. 2019;568:230–234. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittendrigh CS. On temperature independence in the clock system controlling emergence time in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1954;40:1018–1029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.40.10.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majercak J, Sidote D, Hardin PE, Edery I. How a circadian clock adapts to seasonal decreases in temperature and day length. Neuron. 1999;24:219–230. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80834-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto A, Matsumoto N, Harui Y, Sakamoto M, Tomioka K. Light and temperature cooperate to regulate the circadian locomotor rhythm of wild type and period mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Insect Physiol. 1998;44:587–596. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(98)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishimoto H, Lark A, Kitamoto T. Factors that differentially affect daytime and nighttime sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. Front. Neurol. 2012;3:24. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamaze A, et al. Regulation of sleep plasticity by a thermo-sensitive circuit in Drosophila. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40304. doi: 10.1038/srep40304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parisky KM, Agosto Rivera JL, Donelson NC, Kotecha S, Griffith LC. Reorganization of sleep by temperature in Drosophila requires light, the homeostat, and the circadian clock. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendricks JC, et al. Rest in Drosophila is a sleep-like state. Neuron. 2000;25:129–138. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80877-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw PJ, Cirelli C, Greenspan RJ, Tononi G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emery P, Stanewsky R, Hall JC, Rosbash M. A unique circadian-rhythm photoreceptor. Nature. 2000;404:456–457. doi: 10.1038/35006558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng IF, et al. Temperature-dependent developmental plasticity of Drosophila neurons: cell-autonomous roles of membrane excitability, Ca2+ influx, and cAMP signaling. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:12611–12622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2179-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanouye MA, Ferrus A, Fujita SC. Abnormal action potentials associated with the Shaker complex locus of Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:6548–6552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Port F, Chen HM, Lee T, Bullock SL. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E2967–E2976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405500111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seidner G, et al. Identification of neurons with a privileged role in sleep homeostasis in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:2928–2938. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fei H, et al. Mutation of the Drosophila vesicular GABA transporter disrupts visual figure detection. J. Exp. Biol. 2010;213:1717–1730. doi: 10.1242/jeb.036053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakai T, Kasuya J, Kitamoto T, Aigaki T. The Drosophila TRPA channel, painless, regulates sexual receptivity in virgin females. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:546–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masuyama K, Zhang Y, Rao Y, Wang JW. Mapping neural circuits with activity-dependent nuclear import of a transcription factor. J. Neurogenet. 2012;26:89–102. doi: 10.3109/01677063.2011.642910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayser MS, Yue Z, Sehgal A. A critical period of sleep for development of courtship circuitry and behavior in Drosophila. Science. 2014;344:269–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1250553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beckwith, E. J., Geissmann, Q., French, A. S. & Gilestro, G. F. Regulation of sleep homeostasis by sexual arousal. Elife6, e27445 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Gasnier B. The SLC32 transporter, a key protein for the synaptic release of inhibitory amino acids. Pflug. Arch. 2004;447:756–759. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Featherstone DE, et al. Presynaptic glutamic acid decarboxylase is required for induction of the postsynaptic receptor field at a glutamatergic synapse. Neuron. 2000;27:71–84. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrison NL. Mechanisms of sleep induction by GABA(A) receptor agonists. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68:6–12. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okada R, Awasaki T, Ito K. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated neural connections in the Drosophila antennal lobe. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;514:74–91. doi: 10.1002/cne.21971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Enell L, Hamasaka Y, Kolodziejczyk A, Nassel DR. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling components in Drosophila: immunocytochemical localization of GABA(B) receptors in relation to the GABA(A) receptor subunit RDL and a vesicular GABA transporter. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;505:18–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.21472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donlea JM, Thimgan MS, Suzuki Y, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. Inducing sleep by remote control facilitates memory consolidation in Drosophila. Science. 2011;332:1571–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1202249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan Q, Song Y, Yang CH, Jan LY, Jan YN. Female contact modulates male aggression via a sexually dimorphic GABAergic circuit in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:81–88. doi: 10.1038/nn.3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu X, Krause WC, Davis RL. GABAA receptor RDL inhibits Drosophila olfactory associative learning. Neuron. 2007;56:1090–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aronstein K, Ffrench-Constant R. Immunocytochemistry of a novel GABA receptor subunit Rdl in Drosophila melanogaster. Invert. Neurosci. 1995;1:25–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02331829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feinberg EH, et al. GFP Reconstitution across synaptic partners (GRASP) defines cell contacts and synapses in living nervous systems. Neuron. 2008;57:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gordon MD, Scott K. Motor control in a Drosophila taste circuit. Neuron. 2009;61:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Macpherson LJ, et al. Dynamic labelling of neural connections in multiple colours by trans-synaptic fluorescence complementation. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:10024. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cavanaugh DJ, Vigderman AS, Dean T, Garbe DS, Sehgal A. The Drosophila circadian clock gates sleep through time-of-day dependent modulation of sleep-promoting neurons. Sleep. 2016;39:345–356. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donlea, J. M. et al. Recurrent circuitry for balancing sleep need and sleep. Neuron, 97, 378–389.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Ni, J. D. et al. Differential regulation of the Drosophila sleep homeostat by circadian and arousal inputs. Elife8, e40487 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Qian, Y. et al. Sleep homeostasis regulated by 5HT2b receptor in a small subset of neurons in the dorsal fan-shaped body of drosophila. Elife6, e26519 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Yao Z, Macara AM, Lelito KR, Minosyan TY, Shafer OT. Analysis of functional neuronal connectivity in the Drosophila brain. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;108:684–696. doi: 10.1152/jn.00110.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grimley JS, et al. Visualization of synaptic inhibition with an optogenetic sensor developed by cell-free protein engineering automation. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:16297–16309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4616-11.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shafer OT, et al. Widespread receptivity to neuropeptide PDF throughout the neuronal circadian clock network of Drosophila revealed by real-time cyclic AMP imaging. Neuron. 2008;58:223–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buguet A. Sleep under extreme environments: effects of heat and cold exposure, altitude, hyperbaric pressure and microgravity in space. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007;262:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okamoto-Mizuno K, Mizuno K. Effects of thermal environment on sleep and circadian rhythm. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2012;31:14. doi: 10.1186/1880-6805-31-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barbagallo B, Garrity PA. Temperature sensation in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2015;34:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Venkatachalam K, Montell C. TRP channels. Annu Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:387–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang F, Zheng J. High temperature sensitivity is intrinsic to voltage-gated potassium channels. Elife. 2014;3:e03255. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Venner A, Anaclet C, Broadhurst RY, Saper CB, Fuller PM. A Novel Population of Wake-Promoting GABAergic Neurons in the Ventral Lateral Hypothalamus. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:2137–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shrivastava AN, Triller A, Sieghart W. GABA(A) Receptors: post-synaptic co-localization and cross-talk with other receptors. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2011;5:7. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2011.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu F, et al. Direct protein-protein coupling enables cross-talk between dopamine D5 and gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors. Nature. 2000;403:274–280. doi: 10.1038/35002014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brunig I, Sommer M, Hatt H, Bormann J. Dopamine receptor subtypes modulate olfactory bulb gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2456–2460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flores-Hernandez J, et al. D(1) dopamine receptor activation reduces GABA(A) receptor currents in neostriatal neurons through a PKA/DARPP-32/PP1 signaling cascade. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2996–3004. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goffin D, et al. Dopamine-dependent tuning of striatal inhibitory synaptogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:2935–2950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4411-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Artiushin G, Sehgal A. The Drosophila circuitry of sleep-wake regulation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2017;44:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Donlea JM. Neuronal and molecular mechanisms of sleep homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017;24:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pfeiffenberger C, Lear BC, Keegan KP, Allada R. Processing sleep data created with the Drosophila Activity Monitoring (DAM) System. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010;2010:pdb prot5520. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wobbrock, J. O., Findlater, L., Gergle, D. & Higgins, J. J. The aligned rank transform for nonparametric factorial analyses using only anova procedures. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 143–146 (Association for Computing Machinery, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011).

- 78.Kay, M. & Wobbrock, J. O. ARTool: R package for the aligned rank transform for nonparametric factorial ANOVAs. https://github.com/mjskay/ARTool (2019).

- 79.Lenth, R., Singmann, H., Love, J., Buerkner, P. & Herve, M. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html (2019).

- 80.Nicolai LJ, et al. Genetically encoded dendritic marker sheds light on neuronal connectivity in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20553–20558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010198107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the paper or available from the corresponding author upon request.