Abstract

Despite improvements in surgery and medical treatments, epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) remains the most lethal gynaecological malignancy. Aim of this study is to investigate the preclinical immunotherapy activity of cytokine-induced killer lymphocytes (CIK) against epithelial ovarian cancers, focusing on platinum-resistant settings. We generated CIK ex vivo starting from human peripheral blood samples (PBMCs) collected from EOC patients. Their antitumor activity was tested in vitro and in vivo against platinum-resistant patient-derived ovarian cancer cells (pdOVCs) and a Patient Derived Xenograft (PDX), respectively. CIK were efficiently generated (48 fold median ex vivo expansion) from EOC patients; pdOVCs lines (n = 9) were successfully generated from metastatic ascites; the expression of CIK target molecules by pdOVC confirmed pre and post treatment in vitro with carboplatin. The results indicate that patient-derived CIK effectively killed autologous pdOVCs in vitro. Such intense activity was maintained against a subset of pdOVC that survived in vitro treatment with carboplatin. Moreover, CIK antitumor activity and tumor homing was confirmed in vivo within an EOC PDX model. Our preliminary data suggest that CIK are active in platinum resistant ovarian cancer models and should be therefore further investigated as a new therapeutic option in this extremely challenging setting.

Subject terms: Ovarian cancer, Tumour immunology

Introduction

Standard therapy of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) includes cytoreductive surgery to no residual disease associated with platinum-based chemotherapy1–3. Unfortunately recurrence rate of remains high and at the day EOC represent the main cause of death among gynecological neoplasm for women in developed countries4,5. It’s reported that platinum-based re-challenging brings benefit in platinum-sensitive patients, while platinum-resistant patients are treated with single-agent chemotherapy (e.g., pegylated liposomal doxorubicin6,7 paclitaxel8 gemcitabine9, topotecan10,11, or docetaxel11,12). Several new drugs have been recently approved, such as bevacizumab13–16 and PARP inhibitors17–23, for BRCA-mutated EOCs, but nevertheless the prognosis remains severe and it is necessary discovered new strategies to prevent tumor spreading, progression and overcome drug resistance.

In the last few years strong evidence showed that immunotherapy is effective both in solid and hematological malignancies. Currently, most of the efforts are directed towards immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA4) which are able to induce long lasting remissions in specific settings of metastatic solid tumors (e.g. melanoma, Non small cell lung cancer), although if still in limited numbers of patients24–27. Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown activity but only in small subsets of EOC patients with BRCA mutations or microsatellite instability (MSI)28. Defects in tumor antigen presentation and antigen-presenting machinery are emerging among the possible causes of resistance to immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors29. An MHC unrestricted cell based approach with cytokine-induced killer (CIK) lymphocytes could help to overcome some limitations emerged with other immunotherapies based on checkpoint inhibitors30–34. CIK, firstly described in the early 1990s, exert MHC-unrestricted antitumor activity35,36 and represent a subgroup of heterogeneous T lymphocytes expanded ex vivo with mixed T-NK phenotype. CIK can be easily expanded starting from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), cord blood37,38, bone marrow39 or other sources40, in presence of INF-ϒ, Ab-anti-CD3 and interleukin 2 (IL2)41. The cytotoxic activity is mostly mediated by the interaction of their NKG2D membrane receptor with several members of stress-inducible molecules expressed on tumors, such as UL-16–binding proteins (ULBPs) and MHC class I-related chain A and B (MIC A/B)42,43.

It has already been reported that MICA/B and ULBPs are expressed on EOC tumors and are associated with poor prognosis44,45.

Strong preclinical evidence46–49 and early clinical trials with CIK have shown encouraging findings in challenging settings such as metastatic lung cancer, liver cancer, cervical cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, leukemia, soft tissue-sarcoma and melanoma. Moreover, some preclinical works underscore the killing capacity of CIK even against ovarian cancer cells in vitro30,50,51. We built on this evidence and focused our attention on the setting of platinum resistant ovarian cancer, exploring the antitumor activity of autologous CIK against chemoresistance patient-derived ovarian cancer cell lines (pdOVC).

Results

Generation and characterization of patient-derived ovarian cancer cell lines (pdOVC)

pdOVC were successfully established from patients with advanced EOC in 4 to 12 weeks; characteristics of the 9 patients are shown in Table 1. Notably, 6 out of 9 pdOVC cultures were established from relapsed heavily treated chemotherapy resistant patients, while the remaining 3 were established from first relapse.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of ovarian cancer patients and corresponding tumor cell lines.

| ID | Age | Mutated germline BRCA | Stage at diagnosis | Histology | Tumor grade | Number of previous lines of chemotherapy | Chemotherapic agents employed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pdOVC 02 | 73 | BRCA 1 mutated | IV | serous | G3 | 2 | carboplatin, paclitaxel |

| pdOVC 03 | 69 | unknown | IV | serous | G3 | 2 | cisplatin, PLD |

| pdOVC 04 | 61 | unknown | IIIc | serous | G3 | 2 | carboplatin, paclitaxel |

| pdOVC 05 | 45 | unknown | IIIc | serous | G3 | 3 | carboplatin, paclitaxel, bevacizumab, trabectedin, gemcitabine |

| pdOVC 06 | 53 | unknown | IIIc | serous | G1 | 1 | carboplatin, paclitaxel |

| pdOVC 07 | 56 | BRCA 2 mutated | IIIc | serous | G3 | 0 | na |

| pdOVC 08 | 67 | unknown | unknown | serous | borderline | 2 | carboplatin, paclitaxel |

| pdOVC 12 | 43 | BRCA 1 mutated | IIIc | serous | G3 | 0 | na |

| pdOVC 14 | 52 | unknown | IV | serous | G3 | 0 | na |

Abbreviations: na: not applicable.

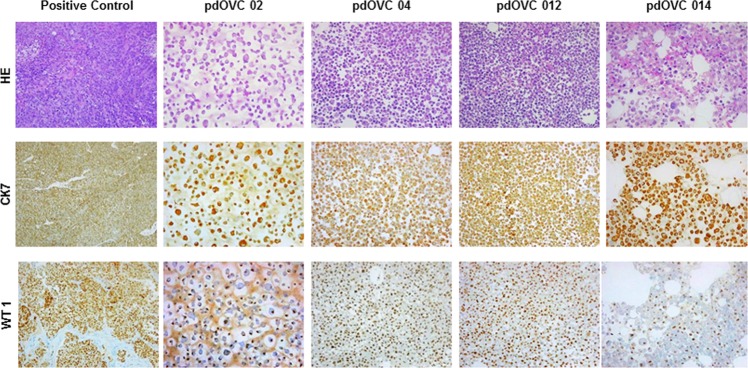

Patient-derived ovarian cancer cells displayed morphologic features consistent with the pathology evaluation of the corresponding tumor and were characterized with IHC analysis for the expression of ovarian cancer marker WT152 and epithelial marker cytokeratin 753 (Fig. 1). We explored the expression of MHC class I molecules on all pdOVC (Table 2), along with their membrane expression of main ligands recognized by CIK (MICA/B, ULBP1, ULBP2/5/6, ULBP3). We found that pdOVC presented variable but consistent expression of ULBP2/5/6, (median 95%,range 22–99%), MICA/B (median 37,5%, range 10%-93. All pdOVCs expressed HLA class I molecules (median 94%, range 72–99%); comparable expression of CIK ligands was confirmed in 5 commercially available ovarian cancer cell lines: A2780, IGROV-1, OAW42, OVCAR3, OVCAR 5 (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Patient derived ovarian cancer cell lines retain the expression of ovarian cancer marker WT1 and cytokeratin 7. Images of pOVC cell cultures obtained from ascites of patients affected by ovarian cancer. Image shows representative pictures of four different cultures expressing ovarian cancer marker WT1 and epithelial marker CK7 (10X magnitude). Positive control: high grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer; Abbreviations: WT1: Wilms’ Tumor 1; CK7: cytokeratin 7; HE: hematoxiliyn eosin.

Table 2.

Membrane expression of NKG2D ligands and HLA class I molecules by ovarian cancer cell lines.

| ID | MIC A/B* | ULBP2,5,6* | Class-I HLA* |

|---|---|---|---|

| pdOVC 02 | ne | 63 | 97 |

| pdOVC 03 | ne | 99 | 93 |

| pdOVC 04 | 91 | 99 | 99 |

| pdOVC 05 | ne | 22 | 90 |

| pdOVC 06 | 26 | 68 | 94 |

| pdOVC 07 | 93 | 99 | 72 |

| pdOVC 08 | 49 | 93 | 96 |

| pdOVC 09 | 10 | 97 | 94 |

| pdOVC 12 | 18 | 95 | 91 |

| MEDIAN | 37,5 | 61 | 94 |

| OVCAR 3 | 59 | 91 | 84 |

| OVCAR 5 | 11 | 92 | 98 |

| OAW42 | 48 | 53 | 97 |

| A2780 | 9 | 24 | 96 |

| IGROV 1 | ne | 48 | 94 |

| MEDIAN | 29,5 | 53 | 96 |

*Values are expressed as percentage of viable positive cells assessed by flow cytometry.

Abbreviations: ne: not expressed.

CIK efficiently kill ovarian cancer in vitro

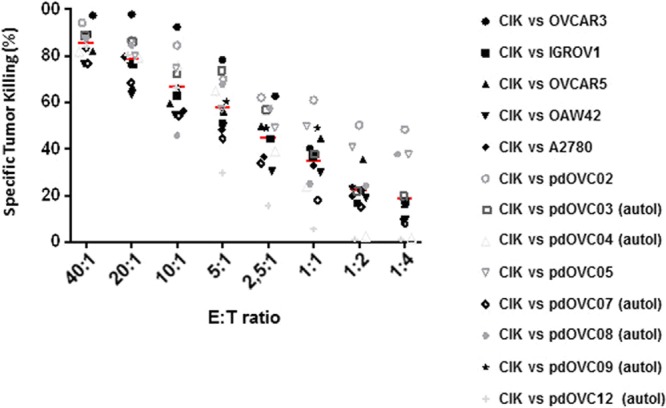

We ex vivo expanded CIK from 14 patients suffering from EOC; CIK were obtained starting from fresh PBMCs cultured with the timely addition of IFN-γ, Ab-anti-CD3, and IL-2. Median expansion of bulk CIK, after 3–4 weeks of culture, was 48 fold (range 12–88). The median rate of mature CIK co-expressing CD3 and CD56 molecules (CD3+CD56+) was 33% (range 19–61%), and 87% (range 73–96%) of CIK were also CD8+. The median membrane expression of the NKG2D receptor, which is the main receptor responsible for tumor recognition, was 90% (range: 78–97%). A summary of patient characteristics and the relevant CIK expansion data are reported in Table 3. In selected experiments we performed a deeper phenotype analysis, including the additional i) antitumor receptor DNAM (median expression 90, range 85–99), ii) immune-checkpoint: molecules PD1 (median expression 31, range 10–60), TIM3 (median expression 64, range 41–93), LAG3 (median expression 6, range 0–15), TIGIT (median expression 29, range 17–35), iii) Natural Killer activation molecules: NKp44 (median expression 1, range 2–1), NKp 30 (median expression 9, range 8–13), NKp46 (median expression 2, range 1–6), iv) TCRαβ (median expression 96, range 87–97), TCRϒδ (median expression 2, range 1–9), v) lymphocyte subsets: effector memory (EM, median expression 63, range 42–65), effector memory-RA (EM RA median expression 20, range 13–30), central memory (CM, median expression 8, range 6–9), Naive (median expression 15, range 12–17) (Supplementary Fig. 1). At the end of CIK expansion we tested their capability to kill ovarian cancers in vitro. We could reproduce the autologous CIK/pdOVC setting in 6 experiments, while allogenic targets (2 pdOVC and 5 commercially available ovarian cancer cell lines) were used in 7 cases when autologous PBMC were not available. Mean values of tumor specific killing at decreasing effector/target (E/T) ratios were 82% ± 3 (40:1), 73% ± 2 (20:1), 61% ± 3 (10:1), 49% ± 3(5:1), 34% ± 6 (2,5:1), 26% ± 5 (1:1), 15% ± 4 (1:2), 12% ± 3 (1:4), assessed by luminescent cell viability assays (Fig. 2). The killer activity of CIK was further confirmed by flow cytometry based independent experiments. We did not observe any difference in the intensity of CIK tumor killing against either autologous or allogeneic pdOVC targets (n = 6) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics and corresponding generation of CIK cells.

| ID | Age | Mutated germline BRCA | Stage at diagnosis | Histology | Tumor grade | Number of previous lines of chemotherapy | Chemotherapic agents employed | Mature NKGD2D° | Mature CD3/CD8° | Mature CD3/CD56° | Final CD3 Fold Increase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIK 01 | 78 | BRCA 1 mutated | IV | serous | G2 | 1 | carboplatin, paclitaxel | 90 | 96 | 46 | 70 | |

| CIK 02 | 73 | BRCA 1 mutated | IV | serous | G3 | 2 | carboplatin, paclitaxel | 93 | 90 | 34 | 34 | |

| CIK 03* | 69 | unknow | IV | serous | G3 | 2 | cisplatin, PLD | 97 | 87 | 21 | 12 | |

| CIK 04* | 61 | unknow | IIIc | serous | G3 | 2 | carboplatin, paclitaxel | 78 | 90 | 37 | 40 | |

| CIK 05 | 45 | unknow | IIIc | serous | G3 | 3 | carboplatin, paclitaxel, bevacizumab, trabectedin, gemcitabine | 87 | 73 | 30 | 18 | |

| CIK 06* | 53 | unknow | IIIc | serous | G1 | 1 | carboplatin, paclitaxel | 96 | 94 | 27 | 87 | |

| CIK 07* | 56 | BRCA 2 mutated | IIIc | serous | G3 | 0 | na | 89 | 90 | 36 | 77 | |

| CIK 08* | 67 | unknow | unknown | serous | borderline | 2 | carboplatin, paclitaxel | 94 | 79 | 40 | 88 | |

| CIK 09 | 56 | unknow | unknown | serous | G3 | 2 | carboplatin, paclitaxel | 86 | 91 | 61 | 55 | |

| CIK 10 | 45 | unknow | IIIc | serous | G3 | 1 | carboplatin, paclitaxel, bevacizumab | 93 | 94 | 19 | 15 | |

| CIK 11 | 59 | unknow | IIIc | serous | G3 | 1 | carboplatin, paclitaxel | 90 | 87 | 27 | 39 | |

| CIK 012* | 43 | BRCA 1 mutated | IIIc | serous | G3 | 0 | Na | 87 | 94 | 33 | 36 | |

| CIK 13 | 58 | WT | IV | na | na | 1 | PLD | 74 | 75 | 44 | 53 | |

| CIK 14 | 71 | WT | IIIC | serous | G3 | 2 | PLD | 76 | 73 | 20 | 83 | |

| MEDIAN | 90 | 87 | 34 | 48 |

*Patients from whom we generated pdOVC cell lines.

°Value expressed as percentage of viable positive cells.

Abbreviations: na: not applicable.

Figure 2.

Patient-derived CIK effectively kill ovarian cancer cells. CIK lymphocytes efficiently killed in vitro ovarian cancer targets, including 6 cell lines generated from metastatic ascites post failure of platinum chemotherapy. CIK were autologous in 6/13 experiments. Tumor killing was assessed by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay following 72 hour co-culture of mature CIK with ovarian targets. Symbols represent the average mortality for each pdOVC (n = 3 for each target), red dash represents mean values of tumor-specific killing for each E/T ratio.

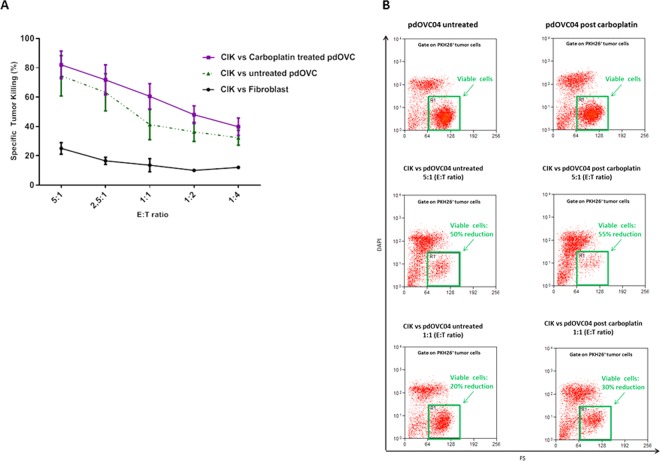

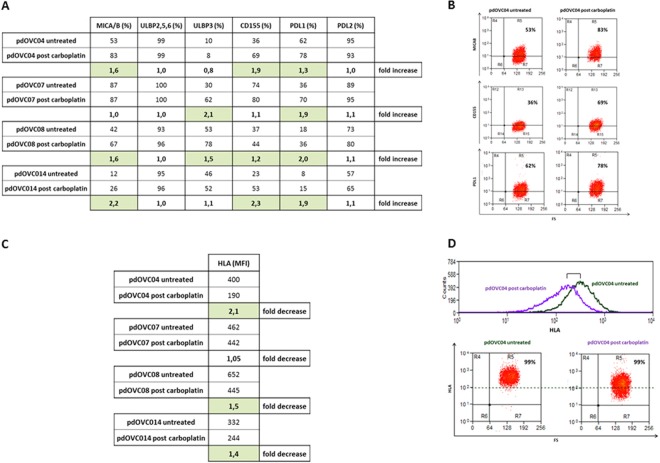

In selected experiments (n = 4) we explored and confirmed that patient-derived CIK effectively kill pdOVC that survived a previous treatment in vitro with therapeutic doses (30 μM, IC50) of Carboplatin. The killing activity was comparable, with a clear trend toward superiority, to that observed versus paired platinum-untreated controls. The mean values of tumor specific killing for platinum-surviving pdOVC, and respective platinum-untreated controls, were: 82% vs 74% (E/T 5:1), 72% vs 63% (E/T 2,5:1), 60% vs 41% (E/T 1:1), 48% vs 36% (E/T 1:2), 39% vs 32% (E/T 1:4) (Fig. 3A,B). We observed that stress-inducible NKG2D ligands, recognized by CIK, trended to be higher on pdOVC that survived the in vitro treatment with carboplatin: mean values expression were 48,5% vs 65,75% for MICAB, 39,75% vs 50% for ULBP3, 42,5% vs 61,5% for CD155, 31% vs 49,75% for PDL1, comparing untreated pdOVC with platinum-surviving pdOVC (Fig. 4A,B). These results support the rationale for the observed enhanced killing by CIK (Fig. 3A,B). The role of the NKG2D receptor was further confirmed in selected experiments where its selective blocking sensibly impaired reduction, 69% vs 38% (E/T 5:1) and 59% vs 33% (E/T 1:1), even if not abrogated, the pdOVC killing by CIK (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 3.

In vitro activity of CIK against chemo-surviving pdOVC. (A) CIK are capable of killing residual pdOVC that survived therapeutic doses (IC50, 72 hours) of carboplatin in vitro. CIK cytotoxicity is fully comparable, with a trend to superiority, with paired control against untreated pdOVC. (B) Tumor killing was evaluated by flow cytometry. The figure shows representative flow-cytometry dot plots reporting the decrease of viable tumor cells during treatment with CIK.

Figure 4.

Membrane expression of NKG2D ligands in pdOVC after treatment with carboplatin. (A,B) The expression by pdOVC of target molecules recognized by CIK, NKG2D and DNAM ligands were confirmed to be highly expressed, even trending to increase, after in vitro treatment with Carboplatin, sustaining the observed effective cytotoxic effect. Expression rates for each molecule and representative flow cytometry dot plots are reported. (C) A relative trend toward decreased expression of HLA class I molecules was observed in pdOVC surviving chemotherapy treatment in vitro. Representative flow-cytometry histograms and plots are reported.

Interestingly, following the treatment in vitro with carboplatin, the residual pdOVC presented a lower intensity of HLA-I expression (Fig. 4C,D), providing further relevance to the potential benefit in clinical perspective from an HLA-independent approach with CIK immunotherapy.

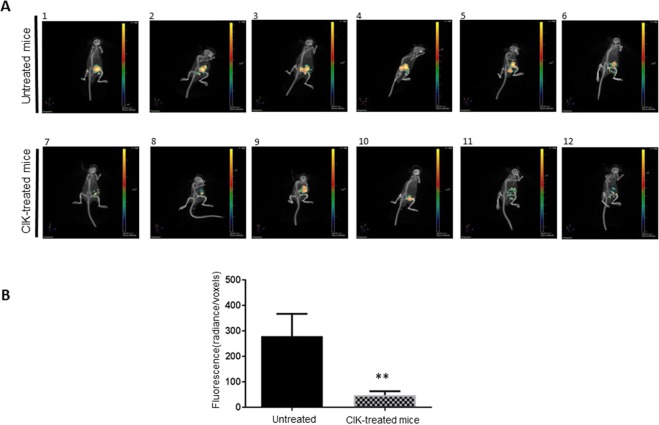

In vivo activity of CIK against ovarian cancer

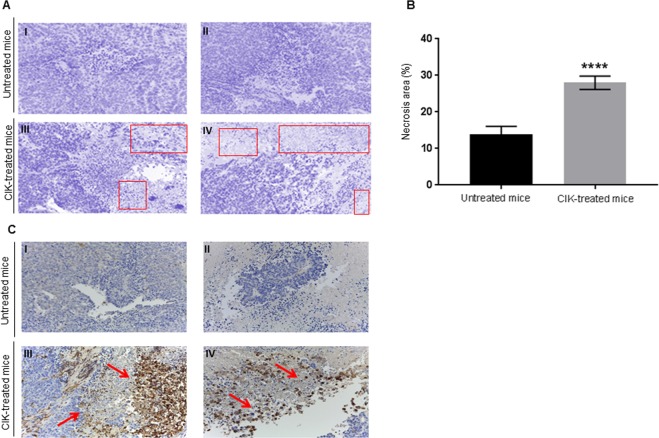

The antitumor activity of CIK was explored in vivo within a patient-derived high grade serous ovarian cancer xenograft model (PDX) obtained from an omental node of a chemo-naïve 75 years old patient54. ϒ null-NOD/SCID mice were subcutaneously injected with the PDX ovarian tumor sample (125 mm3, see methods). Starting 2 weeks after tumor implantation, mice (n = 6) were treated with 2 weekly intravenous infusions of mature CIK (1 × 107) for 5 weeks; mice injected with PBS alone were used as the untreated control (n = 6). Adoptive immunotherapy with CIK significantly reduced tumor cell viability, evaluated by tumor-glucose uptake in vivo, compared to untreated controls (p = 0.0022) (Fig. 5). Mice were sacrificed 10 days after the last CIK infusion observing i) higher rates of necrotic areas in treated mice compared with untreated controls (28% vs 14%, p < 0.0001, panel A and B, Fig. 6) and ii) detectable rates of human tumor infiltrating CIK (CD3+, 35% ± 5), mostly located near the necrotic tissue in treated tumors (panel C, Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

CIK activity in ovarian cancer PDX. (A,B) The antitumor activity of patient-derived CIK was confirmed in vivo within a patient-derived high grade serous (chemo-naïve) ovarian cancer PDX model. The antitumor activity was evaluated by measuring variations in the tumor-glucose uptake in vivo. Representative pictures of tumor-glucose uptake for each mice and cumulative analysis are reported and compared with untreated controls.

Figure 6.

Tumor necrosis and infiltration by CIK in vivo. (A,B) The infusion of CIK lymphocytes determined higher rates of tumor necrosis compared to untreated controls. Representative images (squares indicate necrotic areas) and cumulative data reported (evaluation by color deconvolution method). (C) Representative images (human CD3 IHC staining, Magnification 10×) of CIK tumor infiltration in vivo.

Discussion

Our study reports the preclinical activity of HLA-independent CIK immunotherapy within patient-derived ovarian cancer models, including platinum resistant targets.

Novel surgical techniques and new drugs such as PARP inhibitors and antiangiogenics significantly improved EOC prognosis. Nevertheless, overall clinical outcome, especially after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy, is still severe and novel therapeutic strategies are largely awaited3,55–57. In recent years preclinical studies already suggested the efficacy of CIK against ovarian cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo51, underscoring the role of NKG2D in tumor recognition and possible synergism with bispecific antibodies58.

We confirmed the importance of NDG2D ligands in this setting, reporting their high expression in pdOVC generated from metastatic tumors relapsed after platinum treatment.

It is worth to note however that blocking the NKG2D receptor on CIK reduced but not completely abrogated their killing activity, suggesting the activity of other molecules (e.g. DNAM, LFA-1) partially contributing to the observed antitumor effect. A deeper comprehension of the hierarchy and role of all CIK ligands is warranted as it could help the identification of predictors of response and, as a consequence, subsets of patients that could better benefit from CIK-based immunotherapy.

Early evidence from clinical trials support the feasibility and safety profile of CIK immunotherapy, with initial signs of activity and positive impact on survival outcomes in multiple solid tumors, including ovarian cancer either in advanced31,34,38,42,59–61 or even adjuvant or post-chemotherapy maintenance settings62.

A specific, clinical relevant, issue for translational researches is exploring the killing activity of CIK against relapsed chemo-resistant EOC targets.

Our preclinical model is mainly developed within this frame, with the intent of addressing the emerging need for reliable translational platforms in clinical perspective. The experiments with autologous tumor samples are important in the effort of recapitulating the intrinsic, and mostly unknown, biologic elements that regulate the interface between immune effectors and cancer targets. Patient-derived tumor targets in our work were obtained from metastatic ascites. This could be an important aspect, representative of a realistic clinical scenarios. Metastases may have indeed important biologic and immunogenic differences compared with the primary tumors and, in the hypothesis of clinical translations, CIK immunotherapy will certainly be tested in patients with advanced metastatic disease.

Circulating CIK precursors were obtained directly from PBMC of patients with high grade serous EOCs. Importantly, we observed an intense, ex vivo expansion rates that were not affected by previous or concomitant platinum based treatments. This supports the concept of a procedure that is clinically exploitable, especially in heavily pretreated patients with platinum resistant EOC.

In a clinical perspective, the safe, simple and cost-effective protocol to generate CIK is a valuable issue; this makes CIK strategy compare favorably with other approaches currently under investigation, that include extensive lymphocyte manipulation or genetic engineering. CIK precursors for clinical use may be obtained by leukapheresis or even limited peripheral blood withdrawals, easily repeatable for patients with lower CIK expansion rates that might undergo multiple CIK ex vivo expansion processes. In preparation to clinical trials, the protocol to generate CIK has been recently validated by our and other groups in GMP conditions63.

The activity of patient-derived CIK was also confirmed in vivo within an ovarian cancer xenograft model54.

We performed multiple CIK infusions, hypothesizing that a similar schedule might be replicated also in a hypothetic clinical study. In a clinical prospective, considering the very favorable safety profile of CIK immunotherapy, multiple infusions could be pursued to provide a stronger effect. This animal model, however, was based on a PDX generated from a surgical biopsy collected before the chemotherapy treatment. A more realistic simulation of post-platinum treatment was instead simulated in vitro, observing the effective activity of patient-derived CIK versus pdOVC targets that survived a treatment with therapeutic doses (IC50) with carboplatin. Of note, the stress-inducible NKG2D ligands trended to increase after platinum treatment, supporting the observed CIK cytotoxicity and providing rational to explore combinatorial/sequential approaches with chemotherapy. In conclusion, in the continuously evolving landscape of EOC, where targeted therapies such as PARP inhibitors are acquiring increasing relevance, there is still room for immunotherapy in multiple clinical settings. However, with the exceptions of limited subsets of tumor histotypes (i.e. clear cell OC), checkpoint inhibitors have not replicated the exciting results obtained in other cancers, framing the rationale to explore alternative or complementary strategies like adoptive immunotherapy.

Probably, considering general immunologic axioms suggesting that low tumor burden may elicit a better immunologic control, the optimal clinical setting to develop CIK immunotherapy is probably that of early disease (e.g. after primary or interval cytoreduction) or non-bulky disease relapse.

CIK activity is not impaired by a restrained neoantigen load, as it seems to be the case in most ovarian cancers, nor by intrinsic defects in antigen presentation, HLA integrity or interferon pathways all reported factors linked to failure of checkpoint inhibitors. Furthermore, CIK are ultimately activated T lymphocytes presenting variable expression of PD-1 and other checkpoints. It is conceivable, and currently under investigation in other malignancies, that their antitumor activity may synergize with checkpoint modulators antibodies.

Materials and Methods

Generation and ex-vivo expansion of CIK

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained, by density gradient centrifugation with Lymphoprep (Sentinel Diagnostic), from patients affected by EOC diagnosed at advanced stage at Candiolo Cancer Institute, Fondazione del Piemonte per l’Oncologia (FPO)–IRCCS (Candiolo, Torino, Italy). All individuals provided their written informed consent.

PBMCs were cultured overnight in cell culture flasks at a cell density of 1.5 × 106/mL RPMI (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma) and IFN-γ (1.000 U/ml, PeproTech). After 24 hours in culture anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3, 50 ng/mL, PharMingen) and recombinant human IL-2 (300 U/mL, Miltenyi Biotec S.r.l.) were added. Fresh medium with IL-2 was added as needed.

Phenotype of CIK was analyzed by standard flow cytometric assays. The following monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were used: CD3 (Anti-Human CD3 FITC Mouse, BD PHarmingen™), CD4 (Anti-Human CD4 PE, MACS MiltenyiBiotec), CD8 (Anti-Human CD8 PE, MACS MiltenyiBiotec), CD56 (Anti-Human CD56 APC, MACS MiltenyiBiotec) and CD314–APC (anti-NKG2D; MACS MiltenyiBiotec).

Establishment of patient derived ovarian cancer cell lines (pdOVC)

Freshly isolated ascites were obtained in a sterile vacuum bottle; platinum resistant patients provided consent under institutional review board–approved protocols. 25 ml of fresh ascites fluids were transfer in vented caps T-75cm2 tissue cultures flasks (Corning/Costar) with 25 ml MCDB131/DMEM High-Glucose (1:1) with the addition of penicillin (50 U/mL), streptomycin (50 μg/mL), Glutamax 100 × (all from Gibco BRL), 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Euroclone).

After 3–4 days medium was completely changed; when cells achieved confluence were washed with PBS and trypsinized using trypsin-EDTA solution for 5 minutes at 37 °C.

To confirm that our pdOVC had preserved the morphology and cellular details of tissue samples were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded; the samples were analyzed in collaboration with Pathology department (FPO–IRCCS, Candiolo, Torino, Italy) to confirm the expression of the ovarian cancer markers Wilms’s Tumor 1 (WT1) and epithelial marker cytokeratin 7 (CK7).

Phenotypic analysis of pdOVC was performed using the following fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), allophycocyanin (APC), (Thermo Fisher Scientific) BV421 Violet1, PerCP/CY5, PE-vio770, PE vio615, FITC VioBright, -conjugated mouse mAbs against HLA-ABC (anti-HLA-ABC-FITC, BD Pharmingen) and CIK target molecules (anti-MICA/B, BD Pharmingen; anti-ULBPs, R&D System, Space Import Export; PD1 Miltenyi Biotec; TIM3 Miltenyi Biotec; LAG3 Miltenyi Biotec; TIGIT eBioscience, Inc;, DNAM BD Pharmingen;,NKp44 Miltenyi Biotec; NKp30 Miltenyi Biotec; NKp46 Miltenyi Biotec; TCRαβ, Caltag Laboratories Burlingame ca; TCRϒδ BD Pharmingen; 62 L Miltenyi Biotec; CD45RA Miltenyi Biotec.

We also tested commercially available ovarian cancer cell lines: OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5, IGROW-1, A2780 e OAW42 obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cell lines have been characterized by the provider and maintained as suggested. Phenotypical analysis was conducted as previously described.

In vitro assays of cytotoxicity of patient-derived CIK

The tumor-killing ability of patient-derived CIK was assessed in vitro against ovarian cancer cell lines (either autologous or allogeneic).

The antitumor activity of patient derived CIK was evaluated by a bioluminescent tumor cell viability essay (CellTiter-Glo, Promega). CIK and tumor target cells were co-coltured at various effectors/target ratios (40:1, 20:1, 10:1 5:1, 2,5, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4) for 72 hours in 200 μL of culture medium with 300 U/mL IL2 at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and the measurements were recorded with a GloMax 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega). Growth inhibition at various effectors/target ratios was normalized to CIK untreated tumor cells.

Whenever possible the antitumor activity of patient derived CIK was additionally confirmed by cytofluorimetric analysis. Target cells were stained in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol with the vital dye CFSE (5, 6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester; Molecular Probes) or PKH26 Red Fluorescent Cell Linker kit (Sigma Aldrich). The immune-mediated killing was determined evaluating cell viability by flow cytometry (Cyan ADP, Dako), after 24 hours incubation with expanded CIK cells, as previously described, according to the formula: experimental − spontaneous mortality/(100 − spontaneous mortality) × 100. Cytotoxicity was calculated through flow cytometry (Cyan ADP, Beckman Coulter s.r.l.) using DAPI permeability assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) of target cells. As descriptive statistic al analysis, medians and ranges, mean ± SEM were used as appropriate; statistical significance was expressed as true P value. All P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using software Graph Pad Prism 8.0.

In blocking experiments CIK were pre-incubated with 40 μg/mL of inhibitory anti-NKG2D neutralizing antibody (Clone #149810, R&D Systems).

In vitro assessment of pdOVC sensitivity to carboplatin

pdOVC cells were seeded into 96-well plates (3, 5–4 × 104 cells/well). After overnight incubation, cells were treated with the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) dose carboplatin Carboplatin (Pfizer, 450 mg/45 ml Injection) for 72 h. The cell viability was determined with CellTiter-Glo assay.

In vivo antitumor activity of patient-derived CIK

EOC patient derived xenograft (PDX) model of was carried out as previously described54. Briefly, we implanted subcutaneously in right flank of severely immunocompromised NOD/Shi-scid/IL-2R γnull mice PDX line tumor samples of 125 mm3.Tumor size was evaluated twice-weekly with digital caliper and volume was calculated using the formula 4/3π*(d/2)2*D/2, where d is the minor tumor axis and D is the major tumor axis. All animal procedures were approved by the institutional competent Committee.

Starting 2 weeks after implantation, 6 mice of the “treated group” (CIK) received, twice a week for 5 weeks, intravenous infusions of 1 × 107 mature autologous CIK, resuspended in 1 × PBS (200 μL total volume injected), while 6 mice of the “control group” (CTRL) received PBS alone.

The analysis of tumor metabolic activity was performed using Fluorescent probe XenoLightRediJect 2-DeoxyGlucosone (DG)-750 (Caliper Life Sciences, USA). Fluorescent probe was injected through the mouse tail vein. The tumor location and glucose accumulation was acquired by IVIS® SpectrumCT (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) 4 hours after injection of 2-DG750 and analyzed using Living Image Software (Perkin Elmer, Caliper Life Sciences). To calculate metabolic activity of tumor mass, we acquired 3D images and the ratio between total fluorescence emitted and total number of tumor mass voxels, was calculated. Also in this case, we represented the mean value ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using T software Graph Pad Prism 8. The evaluation of necrotic versus alive cells area was conduct considering the color deconvolution method (acquisition of 10 field for each sample, 10X of magnitude).

Eosin/hematoxylin-stained cells were digitally separated using ImageJ software (version 1.46c; WS Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA,) and an ImageJ plugin for color deconvolution64. The hematoxylin deconvoluted image was subjected to histogram analysis to identify nuclei of alive cells. The total area of alive nuclei were subtracted from estimated total field area (measured and calculated as average in 4 field fully covered of alive cells and used ad reference data) and translate in percentage. Significant Statistical analysis was conducted using software Graph Pad Prism 8.The collection of clinical samples was undertaken with the understanding and written consent of each subject according to the PROFILING Protocol, conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regione Piemonte Ethical Committee (approval no 5141 on 9/3/2011) and then by the IRCCS Ethical Committee (approval no. 192/2016 on 19/7/2016).

All animal procedures were approved by the local Ethical Commission and by the Italian Ministry of Health in accordance with EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments; first authorization was sent on 12/7/2012 and, following subsequent regulations, approved on 14/01/2016 (no. 16/2016-PR) and extended for two additional years on 17/9/2018.

Immunohistochemistry

5 μm in thickness FFPE tissue sections were utilized to visualize morphology of tumor tissues via H&E staining and to detect human lymphocytes with CD3 antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), for CD3 staining, deparaffinization, rehydration and target retrieval were performed following Dako instructions. To quantify data, at least 10 images of each sample were acquired by optical microscope (20×) connected with charge-coupled device (CCD) camera and analyzed by using automatic counter software (NIH ImageJ, W. Rasband, NIH) software. The percentage of necrosis was estimated calculating the difference between a “standard control area” covered by healthy cells and the treated and untreated groups. To define “standard control area” we considered 5H&E fields in which all the area was occupied by round and clearly healthy cells. To calculate the percentage of human lymphocytes in tumors, we compared in the number of all nuclei present in the field versus the number of CD3 positive cells (which are completely absent in non treated tumors).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work supported in part by FPRC ONLUS 5 per mille 2015 Ministero Salute, progetto 357 “Strategy”, to G.V. and MFDR; Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente 2019; FPRC ONLUS 5 per 1000, Ministero Salute 2015 to DS; Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro” (AIRC), IG-2017 n. 20259 to DS, FPRC 5 per mille 2015 Ministero Salute progetto Cancer ImGen to DS.

Author contributions

S.C. study concept, study design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation; J.E. study concept, study design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation; C.M. data analysis and interpretation, manuscript editing, manuscript review; GMes: study concept, immunofluorescence analysis; S.G. clinical data analysis and interpretation; A.P. pathologic revision; manuscripts review; G.M. clinical data analysis and interpretation; E.G. data analysis and interpretation, manuscript editing and manuscript review; M.O. data analysis and interpretation and manuscript review; MFDR manuscript editing and manuscript review, M.A. manuscript editing and manuscript review, D.S. study concept, study design, interpretation, manuscript review; G.V. study concept, study design, interpretation, manuscript review.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: D. Sangiolo and G. Valabrega

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-63634-z.

References

- 1.Vaughan S, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer: recommendations for improving outcomes. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:719–725. doi: 10.1038/nrc3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowtell DD, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer II: reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:668679. doi: 10.1038/nrc4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poveda A, Marth C. Platinum or nonplatinum in recurrent ovarian cancer: that is the question. Future Oncol. 2017;13:11–16. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temkin SM, Bergstrom J, Samimi G, Minasian L. Ovarian Cancer Prevention in High-risk Women. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;60:738–757. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JY, Cho CH, Song HS. Targeted therapy of ovarian cancer including immune check point inhibitor. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2017;32:798–804. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staropoli N, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the management of ovarian cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2014;15:707–720. doi: 10.4161/cbt.28557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrandina G, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the management of ovarian cancer. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2010;6:463–483. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampan, N. C., Madondo, M. T., McNally, O. M., Quinn, M. & Plebanski, M. Paclitaxel and Its Evolving Role in the Management of Ovarian Cancer. Biomed Res Int2015, 10.1155/2015/413076 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ferrandina G, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in progressive or recurrent ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:890–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards SJ, Barton S, Thurgar E, Trevor N. Topotecan, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride, paclitaxel, trabectedin and gemcitabine for advanced recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2015;19:1–480. doi: 10.3310/hta19070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardillo I, et al. Functional and pharmacodynamic evaluation of metronomic cyclophosphamide and docetaxel regimen in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2013;9:1375–1388. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JA, Ngo H, Martin MC, Wolf JK. An evaluation of cytotoxicity of the taxane and platinum agents combination treatment in a panel of human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;98:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aghajanian C, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:2039–2045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman RL, et al. Bevacizumab and paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy and secondary cytoreduction in recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study GOG-0213): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779–791. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30279-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oza AM, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7): overall survival results of a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:928–936. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00086-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark D, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in advanced ovarian cancer: quality-of-life outcomes from the International Collaboration on Ovarian Neoplasms (ICON7) phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:236–243. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70567-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee S, Kaye SB, Ashworth A. Making the best of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010;7:508–519. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farmer H, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fong PC, et al. Poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase inhibition: frequent durable responses in BRCA carrier ovarian cancer correlating with platinum-free interval. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:2512–2519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fong PC, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstantinopoulos PA, Ceccaldi R, Shapiro GI, D’Andrea AD. Homologous Recombination Deficiency: Exploiting the Fundamental Vulnerability of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1137–1154. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledermann JA. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27(Suppl 1):i40–i44. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittica G, et al. PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer. Recent. Pat. Anticancer. Drug. Discov. 2018;13:392–410. doi: 10.2174/1574892813666180305165256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donini C, D’Ambrosio L, Grignani G, Aglietta M, Sangiolo D. Next generation immune-checkpoints for cancer therapy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018;10:S1581–S1601. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.02.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee L, Gupta M, Sahasranaman S. Immune Checkpoint inhibitors: An introduction to the next-generation cancer immunotherapy. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016;56:157–169. doi: 10.1002/jcph.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger AC, et al. A Comprehensive Pan-Cancer Molecular Study of Gynecologic and Breast Cancers. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:690–705.e699. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marin-Acevedo JA, et al. Next generation of immune checkpoint therapy in cancer: new developments and challenges. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018;11:39. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0582-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mittica G, et al. Checkpoint inhibitors in endometrial cancer: preclinical rationale and clinical activity. Oncotarget. 2017;8:90532–90544. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaretsky JM, et al. Mutations Associated with Acquired Resistance to PD-1 Blockade in Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mittica G, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy against ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2016;9:30. doi: 10.1186/s13048-016-0236-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giraudo L, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cells as immunotherapy for solid tumors: current evidence and perspectives. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:999–1010. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jäkel CE, Schmidt-Wolf IG. An update on new adoptive immunotherapy strategies for solid tumors with cytokine-induced killer cells. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2014;14:905–916. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2014.900537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jäkel CE, Vogt A, Gonzalez-Carmona MA, Schmidt-Wolf IG. Clinical studies applying cytokine-induced killer cells for the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors. J. Immunol. Res. 2014;2014:897214. doi: 10.1155/2014/897214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sangiolo D. Cytokine induced killer cells as promising immunotherapy for solid tumors. J. Cancer. 2011;2:363–368. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt-Wolf IG, Negrin RS, Kiem HP, Blume KG, Weissman IL. Use of a SCID mouse/human lymphoma model to evaluate cytokine-induced killer cells with potent antitumor cell activity. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:139–149. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt-Wolf IG, et al. Phenotypic characterization and identification of effector cells involved in tumor cell recognition of cytokine-induced killer cells. Exp. Hematol. 1993;21:1673–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Introna M, et al. Feasibility and safety of adoptive immunotherapy with CIK cells after cord blood transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 2010;16:1603–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golay J, et al. Cord blood-derived cytokine-induced killer cells combined with blinatumomab as a therapeutic strategy for CD19. Cytotherapy. 2018;20:1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishimura R, et al. In vivo trafficking and survival of cytokine-induced killer cells resulting in minimal GVHD with retention of antitumor activity. Blood. 2008;112:2563–2574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-092817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin W, Xiong Y, Chen J, Huang Y, Liu T. DC-CIK cells derived from ovarian cancer patient menstrual blood activate the TNFR1-ASK1-AIP1 pathway to kill autologous ovarian cancer stem cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018;22:3364–3376. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu PH, Negrin RS. A novel population of expanded human CD3 + CD56+ cells derived from T cells with potent in vivo antitumor activity in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. J. Immunol. 1994;153:1687–1696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng Y, et al. Cell-based immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells: From preparation and testing to clinical application. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017;13:1–9. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1285987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bremm M, et al. In-vitro influence of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and Ciclosporin A (CsA) on cytokine induced killer (CIK) cell immunotherapy. J. Transl. Med. 2016;14:264. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai X, et al. Control of Tumor Initiation by NKG2D Naturally Expressed on Ovarian Cancer Cells. Neoplasia. 2017;19:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vyas, M. et al. Soluble NKG2D ligands in the ovarian cancer microenvironment are associated with an adverse clinical outcome and decreased memory effector T cells independent of NKG2D downregulation. Oncoimmunology6, 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1339854 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Mesiano G, et al. Cytokine Induced Killer cells are effective against sarcoma cancer stem cells spared by chemotherapy and target therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1465161. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1465161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gammaitoni L, et al. Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells Kill Chemo-surviving Melanoma Cancer Stem Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:2277–2288. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sangiolo D, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cells eradicate bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Cancer Res. 2014;74:119–129. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gammaitoni L, et al. Effective activity of cytokine-induced killer cells against autologous metastatic melanoma including cells with stemness features. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:4347–4358. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gritzapis AD, Dimitroulopoulos D, Paraskevas E, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Large-scale expansion of CD3(+)CD56(+) lymphocytes capable of lysing autologous tumor cells with cytokine-rich supernatants. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2002;51:440–448. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0298-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HM, et al. Inhibition of human ovarian tumor growth by cytokine-induced killer cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2007;30:1464–1470. doi: 10.1007/bf02977372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taube ET, et al. Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1)–not only a diagnostic but also a prognostic marker in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016;140:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leroy X, Farine MO, Buob D, Wacrenier A, Copin MC. Diagnostic value of cytokeratin 7, CD10 and mesothelin in distinguishing ovarian clear cell carcinoma from metastasis of renal clear cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2007;51:874–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Erriquez J, et al. Xenopatients show the need for precision medicine approach to chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:26181–26191. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ledermann JA. Front-line therapy of advanced ovarian cancer: new approaches. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:viii46–viii50. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pignata S, et al. Treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:viii51–viii56. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC, Ledermann JA. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2014;384:1376–1388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan JK, et al. Enhanced killing of primary ovarian cancer by retargeting autologous cytokine-induced killer cells with bispecific antibodies: a preclinical study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:1859–1867. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu J, et al. Maintenance therapy with autologous cytokine-induced killer cells in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer after first-line treatment. J. Immunother. 2014;37:115–122. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Introna, M. & Correnti, F. Innovative Clinical Perspectives for CIK Cells in Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci19, 10.3390/ijms19020358 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Wang X, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cell/dendritic cell-cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy for the postoperative treatment of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97:e12230. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou Y, et al. Retrospective analysis of the efficacy of adjuvant CIK cell therapy in epithelial ovarian cancer patients who received postoperative chemotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1528411. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1528411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Castiglia S, et al. Correction to: Cytokines induced killer cells produced in good manufacturing practices conditions: identification of the most advantageous and safest expansion method in terms of viability, cellular growth and identity. J. Transl. Med. 2018;16:275. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruifrok AC, Johnston DA. Quantification of histochemical staining by color deconvolution. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 2001;23:291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.