Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a group of anatomic malformations in the heart with high morbidity and mortality. The mammalian heart is a complex organ, the formation and development of which are strictly regulated and controlled by gene regulatory networks of many signaling pathways such as TGF-β. KAT2B is an important histone acetyltransferase epigenetic factor in the TGF-β signaling pathway, and alteration in the gene is associated with the etiology of cardiovascular diseases. The aim of this work was to validate whether KAT2B variations might be associated with CHD. We sequenced the KAT2B gene for 400 Chinese Han CHD patients and evaluated SNPs rs3021408 and rs17006625. The statistical analyses and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium tests of the CHD and control populations were conducted by the software SPSS (version 19.0) and PLINK. The experiment-wide significance threshold matrix of LD correlation for the markers and haplotype diagram of LD structure were calculated using the online software SNPSpD and Haploview software. We analyzed the heterozygous variants within the CDS region of the KAT2B genes and found that rs3021408 and rs17006625 were associated with the risk of CHD.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease, epigenetic factors, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test, KAT2B

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a group of anatomic malformations in the heart and is the most common type of birth defects with high morbidity and mortality [1]. There are two main categories of CHD, cyanotic and acyanotic, with the former including tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), truncus arteriosus (TA) and transposition of the great arteries (TGA), and the latter including ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) [2,3]. Many CHDs are complicated by arrhythmias or heart failure or both [4]. The worldwide prevalence of CHD ranges from 1 to 150 per 1000 neonates [5,6], about 1% of which requires clinical intervention [7].

CHDs are multifactorial heart diseases, involving many genetic variations in development, mostly not of the Mendel’s inheritance mode [8,9], including chromosomal variants such as the 22q11 deletion [6,10]. Over the past decades, numerous genetic defects have been reported for their associations with sporadic or familial CHD cases, leading to better understanding of CHDs [11,12], but the genetic abnormalities of etiological significance for most CHDs remain largely unknown.

In a previous study, we demonstrated the associations of the variant rs2289263 upstream of the SMAD3 gene 5’UTR with increased risk of VSD and variants in the Lefty gene (rs2295418 in Lefty2 and rs360057 in Lefty1) with the risk of other CHD types [2]. LEFTY and SMAD3 both play central roles in the TGF-β signaling pathway [13,14], which is involved in the development of the mammalian heart during embryogenesis together with numerous transcription and epigenetic factors [2,15,16].

KAT2B is an important histone acetyltransferase (HAT) epigenetic factor in the TGF-β signaling pathway. Alteration in epigenetic regulation of gene expression in vascular cells has been associated with the etiology of cardiovascular diseases [17,18]. KAT2B can acetylate the exposed lysines for the modification of histones [19,20]. It is also an important nuclear epigenetic factor that binds to many sequence-specific factors involved in cell growth or differentiation [19]. KAT2B gene variations may lead to vascular disorders and coronary heart abnormalities [21,22].

Based on the documented key roles of KAT2B in the TGF-β signaling pathway and vascular cellular processes, we postulate its associations with CHDs. In the present study, we analyzed the transcribed region and splicing sites of the KAT2B gene and compared the gene sequences between 400 Chinese Han CHD patients and 420 controls. We found that rs3021408 and rs17006625 in the CDS (coding sequence) region of KAT2B gene were associated with the risk of CHDs.

Materials and methods

The study population

From the First, Second and Fourth Affiliated Hospitals of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, we collected specimens of 400 CHDs patients, and from the Medical Examination Center of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, 420 normal controls with no reported cardiac phenotypes or defects were recruited (Table 1). All the CHD patients and normal controls received comprehensive physical examination, electrocardiogram and ultrasonic echocardiogram examinations. None of the patients showed any other cardiac or systematic abnormalities, and the normal controls did not show any defects in the heart or other body parts. Before this work, we had obtained a written informed consent from each participant or their parents on behalf of minors, and the Ethics Committee of the Harbin Medical University approved this work, consistent with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics and analysis of the study population.

| Parameter | CHD | Control | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | 400 | 420 | – |

| Male/Female (n) | 179/221 | 183/237 | |

| Age (years) | 15.53 ± 18.10 | 14.98 ± 9.86 | 0.207 |

Data are shown as mean ± SD between the two groups; there were no statistical differences of the age and gender composition.

DNA and SNP genotyping analysis

As detailed in previous studies [23,24], the genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood leukocytes of the participants. The human KAT2B gene consisting of 17 exons is located on 3p24.3. In order to determine the genotypes of the KAT2B gene, we amplified the 17 exons and the splicing sites of the gene using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method (Supplementary Table S1). All reagents were purchased from the TransGen Biotech company, Beijing, China. The PCR reaction system was 10 × PCR buffer: 5.0 μl, dNTP mixture (2.5 μmol/l): 1.0 μl, rTaq dnase 0.4 μl, up/down primers (10 μmol/l each): 1.0 μl, DNA: 150 ng, add purified water to 50 μl. The products were sequenced using standard protocols [2,25]. Then, the genotypes were determined using PCR (Supplementary Table S2) and gene sequencing methods [26,27].

Statistical analysis

We determined genotypes rs3021408, rs17006625, rs148960024 and rs41285059 within the CDS region of the KAT2B gene (Supplementary Figure S1A) on 400 CHDs patients and 420 normal controls. Using the software SPSS (version 19.0) and PLINK, we carried out the statistical analyses and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium tests of the CHDs and control populations as previously reported [23,27]. The experiment-wide significance threshold, matrix of linkage-disequilibrium (LD) correlation for the markers and haplotype diagram of LD structure were calculated using the Haploview software as previously reported [27].

Multiple sequence alignments

The KAT2B protein sequences of various species were obtained from the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and multiple-sequence alignments and position of the SNPs in the KAT2B protein were carried out using the Vector NTI software [28].

Results

Patients

We recruited the participants from the First, Second and Fourth Affiliated Hospitals of Harbin Medical University and confirmed the clinical diagnosis for each of the patients. They had no history or manifestations of any other disease or systemic abnormalities except CHDs. We also established that their mothers did not take medications or attract infections during her gestation, because such factors have been reported to be associated with heart malformation in pregnancy [29,30].

The 400 CHD patients included 184 with ventricular septal defects (VSD), 131 with atrial septal defects (ASD), 54 with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), 7 with tetralogy of Fallot, 4 with pulmonary stenosis, and 19 with other types of congenital heart defects. The 400 CHD patients (male 179, female 221, with an average age of 15.42 years) and 420 unrelated controls (male 183, female 237, with an average age of 14.02 years) recruited for the present study had no statistical differences in gender composition or age between the two groups (Table 1).

Genotype analysis of the KAT2B gene

We sequenced the KAT2B gene to determine whether genetic variants in the KAT2B gene may confer susceptibility to CHDs. In comparisons of the transcribed regions and splicing sites of KAT2B between the patients and controls, we identified variations rs3021408, rs17006625, rs148960024 and rs41285059 within the CDS region of the KAT2B gene (Supplementary Figure S1A). Further analysis showed that the genetic heterozygosity was very low in rs148960024 and rs41285059, but remarkably high in rs3021408 and rs17006625 (Supplementary Figure S1B).

The genotype and allele distributions of rs3021408 and rs17006625 in the CHD patients and control subjects were shown in Supplementary Table S3. Chi-Square tests showed that the variants rs3021408 and rs17006625 were associated with the risk of CHDs in the Chinese Han population (Table 2). We conducted the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test for the CHDs and controls and it was in line with the equilibrium (Table 3).

Table 2. SNP rs3021408 and rs17006625 in the CDS region of KAT2B gene were associated with the risk of congenital heart diseases in Chinese populations.

| Comparison SNP | Type | Pearson Chi-square | Spearman Correlation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Min count1 | df | Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) | Value | Asymp. Std. error2 | Approx. T3 | Approx. Sig | ||

| rs3021408 | Genotype | 11.6671 | 87.8 | 2 | 0.003 | 0.117 | 0.035 | 3.373 | 0.001 4 |

| Allele | 11.5131 | 369.76 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.084 | 0.025 | 3.403 | 0.001 4 | |

| rs17006625 | Genotype | 5.6821 | 5.37 | 2 | 0.058 | 0.038 | 0.034 | 2.379 | 0.018 4 |

| Allele | 5.4611 | 103.90 | 1 | 0.019 | 0.058 | 0.024 | 2.339 | 0.019 4 | |

The minimum expected count.

Not assuming the null hypothesis.

Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis.

Based on normal approximation.

Table 3. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test for the study population groups.

| SNPs | Genotype | H–W equilibrium testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo/Hetero/Homozygote | O(HET) | E (HET) | P | |

| rs3021408 | 180/398/242 | 0.4854 | 0.4971 | 0.5272 |

| rs17006625 | 11/191/618 | 0.2329 | 0.226 | 0.4424 |

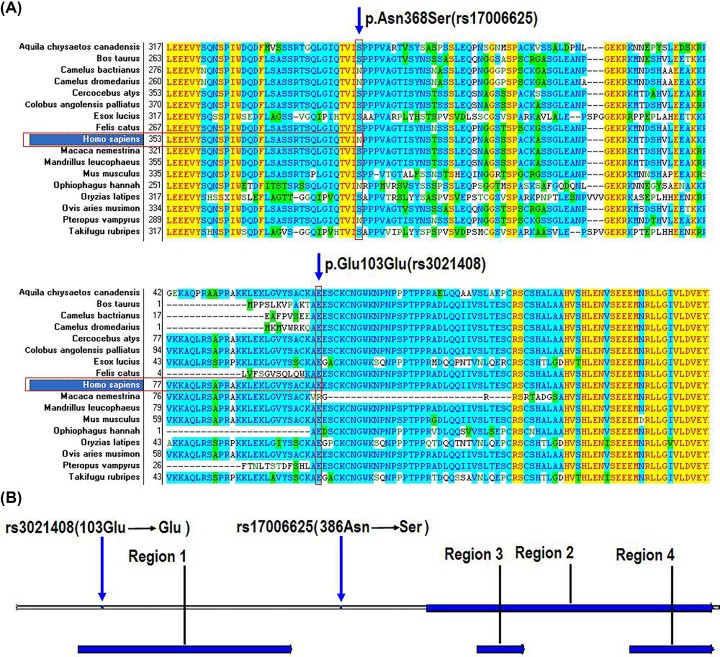

The experiment-wide significance threshold of the variants rs3021408 and rs17006625 in KAT2B gene was 0.027. The Haploview software was used to conduct LD analysis of the variants rs3021408 and rs17006625, and the results were consistent with the data from the HapMap CHB population (Figure 1). The genotype frequencies in the CHD and control groups were further analyzed by three genetic models, including trend, dominant and recessive models, in addition to Chi-square and Fisher tests (Table 4). All those analyses indicated that the variants rs3021408 and rs17006625 were associated with the risk of CHDs.

Figure 1. LD analysis of the variants rs3021408 and rs17006625 in the KAR2B gene.

(A) Data analysis of CHD patients and controls from the present study of variants in KAR2B gene. (B) Data from HapMap CHB of variants in KAR2B gene. The data from the HapMap CHB and this work were consistent.

Table 4. SNP rs3021408 and rs17006625 within KAT2B gene associated with the risk of congenital heart diseases.

| SNPs | Trend model | Dominant model | Recessive model |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs3021408 | 0.00079771 | 0.014391 | 0.0023581 |

| rs17006625 | 0.017621 | 0.018921 | 0.5474 |

statistically significant.

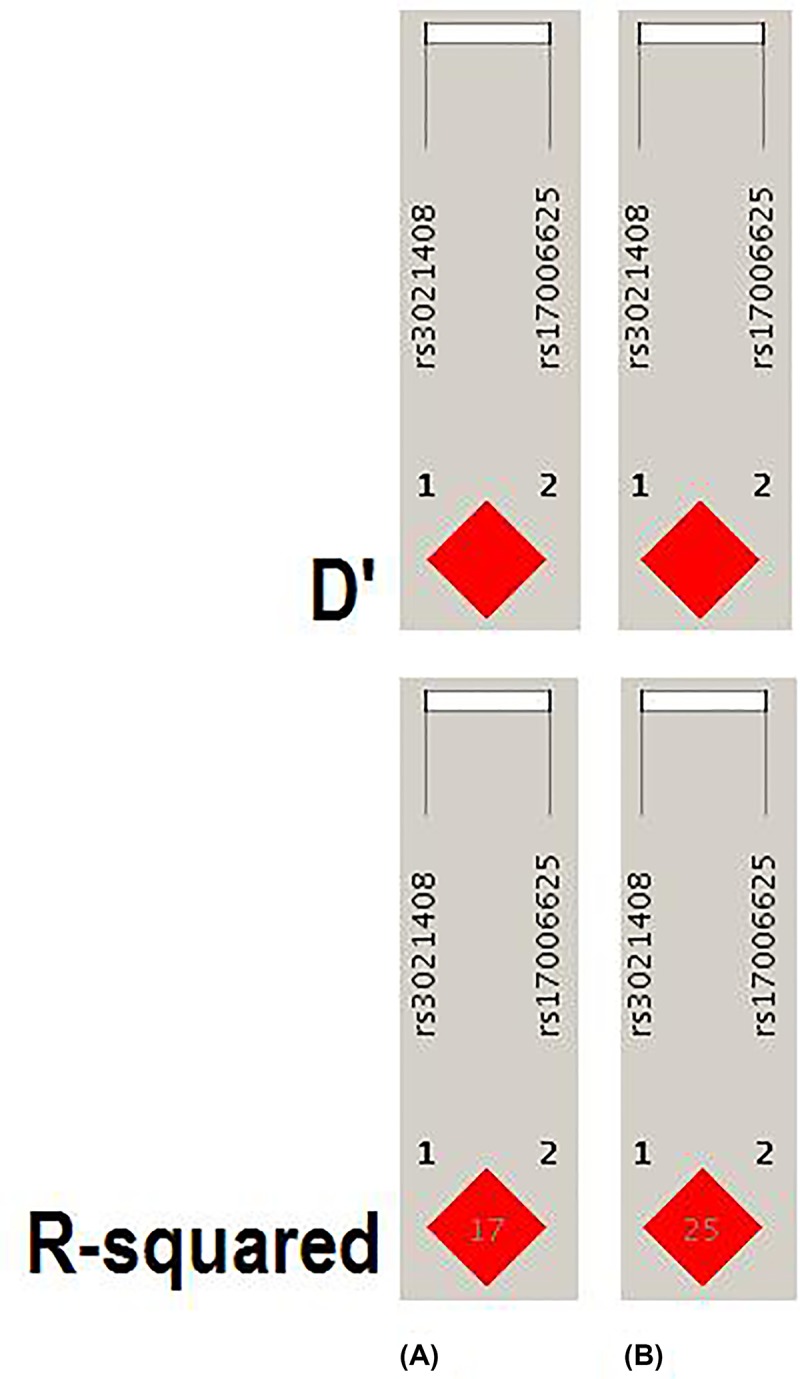

Conservation of the protein in evolution

We also compared the conservativeness of the KAT2B protein sequences from different species including birds, fishes, rodents and primates. Multiple-sequence alignment analysis showed that rs17006625 and rs3021408 were located within the conserved area of the KAT2B protein (Figure 2A), with rs17006625 being located between the first (Homology) and second (AT) functional domain of the KAT2B protein and rs3021408 within the first (Homology) functional domain (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Multiple-sequence alignment and position analysis of rs3021408 and rs17006625.

(A) Multiple-sequence alignment of KAT2B from birds, fishes and mammals (including Homo sapiens, Pan troglodytes, Macaca mulatta etc.). (B) Position analysis of the SNPs in the KAT2B protein.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the transcribed regions and splicing sites of the epigenetic factor KAT2B gene in a large cohort of CHD patients and controls. We found that the variants rs3021408 and rs17006625 in the KAT2B gene were associated with the risk of CHDs in the Chinese Han population, suggesting the possible involvement of the KAT2B gene in the etiology of the disease.

The epigenetic and genetic factors affect many protein expression and metabolic changes in human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Those cells are perfect cell sources for human complex disease modeling and regenerative medicine [26]. The importance of epigenetic factors in human complex diseases can enable us to better understanding for those diseases, and may be used for diseases risk prediction and treatment [21].

During the formation of the human heart many genes and factors are strict temporal, spatial, and sequential expressed and translated [2]. The expression and translation of those genes or factors are regulated by those epigenetic factors [31]. The KAT2B family members are one of the epigenetic factors, have been found implicated in a variety of biological processes and human complex disease [31,32]. This work further emphasized the importance of epigenetic factors especially the KAT2B in the etiology of CHDs.

In the human or eukaryotic cells, the histone proteins are wrapped by DNA and formed the nucleosomes, but it is not only a packaging protein but also a regulatory protein [27]. When the histones are been chemical modified the chromatin structure can be altered, and the accessibility of DNA elements to transcription factors are increased or decreased, that can regulates the transcription of genes [33]. KAT2B is the CREBBP associated factor, that can acetylate many histones and non-histone proteins, and regulates many genes expression involved in cell proliferation [34,35]. It has been found that variations in the KAT2B gene promoter can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease mortality and restenosis [21], and the heterozygous for the low-risk allele patients had about 20 present lower risks of the cardiovascular events and homozygous allele individuals had about 40 present lower risks [21]. In this work, we found many creatures have the G/G allele (p.Ser368) of the rs17006625 and very few creatures have the A/A allele (p.Asn368) including human, Pteropus vampyrus, Ophiophagus Hannah, Camelus bactrianus and Camelus dromedarius. The interesting thing is that more congenital heart diseases patients were likely to have the A/A allele and for the normal population were more likely to have the A/G or G/G allele (Supplementary Table S1).

There are mainly three conserved functional domains in the KAT2B protein sequence, the homology domain, AT domain and bromodomain [36]. The homology domain is located in the N-terminal half of the protein, and the AT domain and bromodomain are located in the C-terminal half [37]. The central region of the AT domain mediates acetyl CoA binding and catalysis, and the N- and C-terminal regions of the AT domain mediates histone substrate specificity [38,39]. It has been found that the normal functions of the protein need the combined actions of homology and AT domains [40]. In this work, we found the rs17006625 (p.Ser368) was located between the homology and AT domains of the protein.

The KAT2B protein homology domain is also contained a potential E3 ligase activity region, that could functions as a ubiquitin E3 ligase for Hdm2, and promotes the p53 protein degradation [41]. So the homology domain of the KAT2B protein plays some roles in regulating cellular p53 levels, and KAT2B underlines the functional connections between cellular acetylation and ubiquitination machineries [42]. In this work, we found the location of the SNP rs3021408 was in the homology domain and E3 ligase activity region. All those showed the important roles of the homology and AT domains for the KAT2B protein, and this is may be the reasons why rs3021408 and rs17006625 in the KAT2B gene were associated with the risk of CHDs.

Conclusion

We analyzed the transcribed regions and splicing sites of the epigenetic factors KAT2B gene between 400 Chinese Han CHD patients and 420 controls, and revealed a correlation between rs3021408 and rs17006625 in the KAT2B gene and risk of CHDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and family members for their cooperation and participation in this study; the physicians for the specimens collection and clinical examinations.

Abbreviations

- CDS

coding sequence

- CHD

congenital heart disease

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- KAT2B

lysine acetyltransferase 2B

- OD260/280

optical density 260/280

Contributor Information

Fei-Feng Li, Email: Lff-1981@163.com.

Gui-Yu Wang, Email: guiywang@gmail.com.

Shu-Lin Liu, Email: slliu@hrbmu.edu.cn.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants of Postdoctoral Foundaction of Heilongjiang Province and innovation project for college students of Harbin Medical University [grant number 201810226070 (to F.F.-L.)]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers NSFC81271786, 81110378, 81030029, 81671980, 81871623 (to S.L.-L.)]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: F.F-.L., G.Y.-W., S.L.-L.; Method: Y.S.-H., F.F.-L., J.Z.-W., S.S., Y.H., J.X.-Z., C.X.; Analysis and investigation: Y.S.-H., F.F.-L., J.Z.-W., S. S., Y.Z., Y.H., J.X. Z., C.X.; Manuscript written: F.F.L., S.L.-L; Manuscript revision: all the authors.

Ethics Approval

Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University.

Patient Consent

Patient consent was obtained.

References

- 1.Teteli R., Uwineza A., Butera Y., Hitayezu J., Murorunkwere S., Umurerwa L. et al. (2014) Pattern of congenital heart diseases in Rwandan children with genetic defects. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 19, 85 10.11604/pamj.2014.19.85.3428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng X., Zhou J., Li F.F., Yan P., Zhao E.Y., Hao L. et al. (2014) Characterization of Nodal/TGF-Lefty Signaling Pathway Gene Variants for Possible Roles in Congenital Heart Diseases. PLoS ONE 9, e104535 10.1371/journal.pone.0104535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodian M., Ngaide A.A., Mbaye A., Sarr S.A., Jobe M., Ndiaye M.B. et al. (2014) Prevalence of congenital heart diseases in Koranic schools (daara) in Dakar: a cross-sectional study based on clinical and echocardiographic screening in 2019 school children. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 108, 32–5 10.1007/s13149-014-0410-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Bom T., Zomer A.C., Zwinderman A.H., Meijboom F.J., Bouma B.J. and Mulder B.J. (2011) The changing epidemiology of congenital heart disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 8, 50–60 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman J.I. and Kaplan S. (2002) The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 39, 1890–1900 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01886-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierpont M.E., Basson C.T., Benson D.W. Jr., Gelb B.D., Giglia T.M., Goldmuntz E. et al. (2007) Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 115, 3015–3038 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman J.I., Kaplan S. and Liberthson R.R. (2004) Prevalence of congenital heart disease. Am. Heart J. 147, 425–439 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oyen N., Poulsen G., Wohlfahrt J., Boyd H.A., Jensen P.K. and Melbye M. (2010) Recurrence of discordant congenital heart defects in families. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 122–128 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.890103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad C. and Chudley A.E. (2002) Genetics and cardiac anomalies: the heart of the matter. Indian J. Pediatr. 69, 321–332 10.1007/BF02723219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thienpont B., Mertens L., de Ravel T., Eyskens B., Boshoff D., Maas N. et al. (2007) Submicroscopic chromosomal imbalances detected by array-CGH are a frequent cause of congenital heart defects in selected patients. Eur. Heart J. 28, 2778–2784 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruneau B.G. (2008) The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature 451, 943–948 10.1038/nature06801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards A.A. and Garg V. (2010) Genetics of congenital heart disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 6, 91–97 10.2174/157340310791162703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Laar I.M., Oldenburg R.A., Pals G., Roos-Hesselink J.W., de Graaf B.M., Verhagen J.M. et al. (2011) Mutations in SMAD3 cause a syndromic form of aortic aneurysms and dissections with early-onset osteoarthritis. Nat. Genet. 43, 121–126 10.1038/ng.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Linde D., van de Laar I.M., Bertoli-Avella A.M., Oldenburg R.A., Bekkers J.A., Mattace-Raso F.U. et al. (2012) Aggressive cardiovascular phenotype of aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome caused by pathogenic SMAD3 variants. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, 397–403 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckingham M., Meilhac S. and Zaffran S. (2005) Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 826–835 10.1038/nrg1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Weerd J.H., Koshiba-Takeuchi K., Kwon C. and Takeuchi J.K. (2011) Epigenetic factors and cardiac development. Cardiovasc. Res. 91, 203–211 10.1093/cvr/cvr138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ordovas J.M. and Smith C.E. (2010) Epigenetics and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 510–519 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartke T. and Kouzarides T. (2011) Decoding the chromatin modification landscape. Cell Cycle 10, 182 10.4161/cc.10.2.14477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahbazian M.D. and Grunstein M. (2007) Functions of site-specific histone acetylation and deacetylation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 75–100 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.162114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi S., Lin J., Cai Y., Yu J., Hong H., Ji K. et al. (2014) Dimeric structure of p300/CBP associated factor. BMC Struct. Biol. 14, 2 10.1186/1472-6807-14-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pons D., Trompet S., de Craen A.J., Thijssen P.E., Quax P.H., de Vries M.R. et al. (2011) Genetic variation in PCAF, a key mediator in epigenetics, is associated with reduced vascular morbidity and mortality: evidence for a new concept from three independent prospective studies. Heart 97, 143–150 10.1136/hrt.2010.199927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duclot F., Jacquet C., Gongora C. and Maurice T. (2010) Alteration of working memory but not in anxiety or stress response in p300/CBP associated factor (PCAF) histone acetylase knockout mice bred on a C57BL/6 background. Neurosci. Lett. 475, 179–183 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X., Shi S., Li F.F., Cheng R., Han Y., Diao L.W. et al. (2017) Characterization of soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor gene STX18 variations for possible roles in congenital heart diseases. Gene 598, 79–83 10.1016/j.gene.2016.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan Z.X., Li F.F., Qu Y.Y., Liu J., Liu G.R., Zhou J. et al. (2012) Identification of a known mutation in Notch 3 in familiar CADASIL in China. PLoS ONE 7, e36590 10.1371/journal.pone.0036590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q., Zhou J., Lei H., Zhu C.Y., Li F.F., Zheng D. et al. (2018) RBPJ polymorphisms associated with cerebral infarction diseases in Chinese Han population: A Clinical Trial/Experimental Study (CONSORT Compliant). Medicine (Baltimore). 97, e11420 10.1097/MD.0000000000011420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita J., Tohyama S., Kishino Y., Okada M. and Morita Y. (2019) Concise Review: Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of Cardiac Differentiation from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cells 37, 992–1002 10.1002/stem.3027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun C.Y., Sun C., Cheng R., Shi S., Han Y., Li X.Q. et al. (2018) Rs2459976 in ZW10 gene associated with congenital heart diseases in Chinese Han population. Oncotarget 9, 3867–3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li F.F., Yan P., Zhao Z.X., Liu Z., Song D.W., Zhao X.W. et al. (2016) Polymorphisms in the CHIT1 gene: Associations with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 7, 39572–39581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Driel L.M., Smedts H.P., Helbing W.A., Isaacs A., Lindemans J., Uitterlinden A.G. et al. (2008) Eight-fold increased risk for congenital heart defects in children carrying the nicotinamide N-methyltransferase polymorphism and exposed to medicines and low nicotinamide. Eur. Heart J. 29, 1424–1431 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kebed K.Y., Bishu K., Al Adham R.I., Baddour L.M., Connolly H.M., Sohail M.R. et al. (2014) Pregnancy and Postpartum Infective Endocarditis: A Systematic Review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 89, 1143–1152 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadoul K., Wang J., Diagouraga B. and Khochbin S. (2011) The tale of protein lysine acetylation in the cytoplasm. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 970382 10.1155/2011/970382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dekker F.J. and Haisma H.J. (2009) Histone acetyl transferases as emerging drug targets. Drug Discov. Today 14, 942–948 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao Q. and Ye S. (2011) The genetics of epigenetics: is there a link with cardiovascular disease. Heart 97, 96–97 10.1136/hrt.2010.214833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ge X., Jin Q., Zhang F., Yan T. and Zhai Q. (2009) PCAF acetylates {beta}-catenin and improves its stability. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 419–427 10.1091/mbc.e08-08-0792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imhof A., Yang X.J., Ogryzko V.V., Nakatani Y., Wolffe A.P. and Ge H. (1997) Acetylation of general transcription factors by histone acetyltransferases. Curr. Biol. 7, 689–692 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00296-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagy Z. and Tora L. (2007) Distinct GCN5/PCAF-containing complexes function as co-activators and are involved in transcription factor and global histone acetylation. Oncogene 26, 5341–5357 10.1038/sj.onc.1210604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterner D.E. and Berger S.L. (2000) Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 435–459 10.1128/MMBR.64.2.435-459.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clements A., Rojas J.R., Trievel R.C., Wang L., Berger S.L. and Marmorstein R. (1999) Crystal structure of the histone acetyltransferase domain of the human PCAF transcriptional regulator bound to coenzyme A. EMBO J. 18, 3521–3532 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marmorstein R. (2001) Structure and function of histone acetyltransferases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 693–703 10.1007/PL00000893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carre C., Szymczak D., Pidoux J. and Antoniewski C. (2005) The histone H3 acetylase dGcn5 is a key player in Drosophila melanogaster metamorphosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8228–8238 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8228-8238.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linares L.K., Kiernan R., Triboulet R., Chable-Bessia C., Latreille D., Cuvier O. et al. (2007) Intrinsic ubiquitination activity of PCAF controls the stability of the oncoprotein Hdm2. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 331–338 10.1038/ncb1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caron C., Boyault C. and Khochbin S. (2005) Regulatory cross-talk between lysine acetylation and ubiquitination: role in the control of protein stability. Bioessays 27, 408–415 10.1002/bies.20210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.