Key Points

Human T cells coexpressing the full-length isoform of Helios with FOXP3 delay disease in a murine graft-versus-host disease model.

The full-length and short isoforms of the transcription factor Helios differentially mediate human Treg function.

Abstract

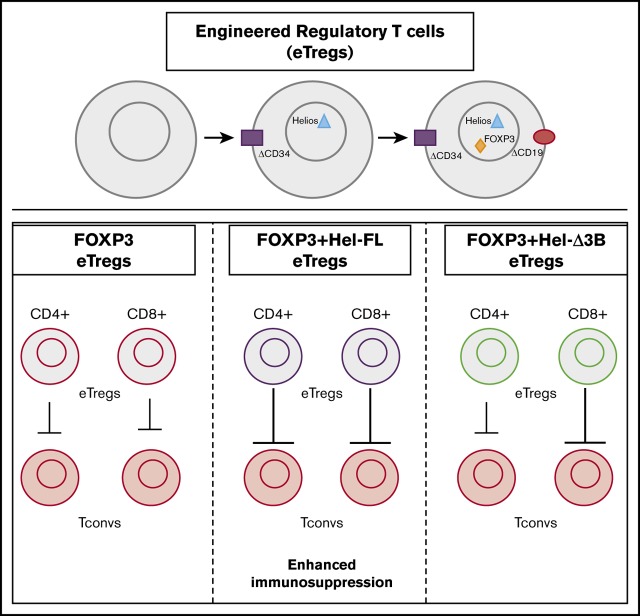

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a subset of immune cells that suppress the immune response. Treg therapy for inflammatory diseases is being tested in the clinic, with moderate success. However, it is difficult to isolate and expand Tregs to sufficient numbers. Engineered Tregs (eTregs) can be generated in larger quantities by genetically manipulating conventional T cells to express FOXP3. These eTregs can suppress in vitro and in vivo but not as effectively as endogenous Tregs. We hypothesized that ectopic expression of the transcription factor Helios along with FOXP3 is required for optimal eTreg immunosuppression. To test this theory, we generated eTregs by retrovirally transducing total human T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) with FOXP3 alone or with each of the 2 predominant isoforms of Helios. Expression of both FOXP3 and the full-length isoform of Helios was required for eTreg-mediated disease delay in a xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease model. In vitro, this corresponded with superior suppressive function of FOXP3 and full-length Helios-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs. RNA sequencing showed that the addition of full-length Helios changed gene expression in cellular pathways and the Treg signature compared with FOXP3 alone or the other major Helios isoform. Together, these results show that functional human CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs can be generated from total human T cells by coexpressing FOXP3 and full-length Helios.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a subset of T cells that mediate immune homeostasis through suppression of immune activity.1-4 Tregs downregulate the immune response via a variety of mechanisms, including inhibiting conventional T-cell (Tconv) proliferation and activation, secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines, killing of immune cells, and induction of anergy. The major Treg subset that has been studied is CD4+ Tregs, which represent 3% to 5% of circulating CD4+ T cells. In addition, there are CD8+ Tregs, which have not been well characterized.5,6

There is intense interest in using Tregs as a cellular therapeutic. Clinical trials are testing the use of natural Tregs in the treatment of multiple inflammatory diseases, including type 1 diabetes, transplant rejection, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).7-11 These trials have shown that CD4+ Treg infusions are safe but only moderately successful. A major challenge is expanding natural CD4+ Tregs to numbers required to treat.9 Another limitation of Treg therapy is isolating a pure population of Tregs. Tregs are commonly isolated by selecting CD4+ CD25+ T cells, but these markers are also expressed by activated Tconvs.12 This scenario leads to potential contamination of Tregs with Tconvs that could exacerbate disease. In addition, natural Tregs can convert to Tconvs and lose immunosuppressive activity in vivo.13-16

Engineered Tregs (eTregs) provide potential solutions to the limitations of natural Tregs. Total CD4+ T cells can be isolated in greater numbers and expanded more quickly than endogenous Tregs. These cells can then be transduced with Treg genes, allowing for the creation of a much larger number of Tregs compared with natural Tregs. Coexpression of Treg genes with a transduction marker allows for purification of eTregs and ensures homogeneity of the cell population.17 Constitutively expressing Treg transcription factors stabilizes the Treg phenotype.18 Although the advantages of eTregs are clear, the Treg genes necessary to create an optimal engineered Treg are still undefined.

High expression of the transcription factor FOXP3 is a hallmark of CD4+ Tregs. Enforced FOXP3 expression in CD4+ T cells generates Tregs capable of mediating in vitro suppression.19 Furthermore, FOXP3-transduced CD4+ T cells can reduce symptoms in murine colitis and GVHD models.20,21 However, in a study using a murine arthritis model, FOXP3-transduced cells were not as effective as endogenous Tregs at reducing joint destruction or decreasing the number of pathogenic T helper 17 cells in the joint.18 In addition, microarray data have shown that FOXP3 is not sufficient to induce a complete Treg gene signature in murine CD4+ T cells.22

In addition to FOXP3, the Ikaros family member Helios is highly expressed in ∼70% of CD4+ FOXP3+ Tregs.23 Helios+ CD4+ Tregs more effectively suppress cytokine production by Tconv cells24,25 and are more stable under inflammatory conditions than Helios– CD4+ Tregs.23,26-28 Mice with Helios deficiency in Foxp3+ cells develop spontaneous autoimmune disease, and CD4+ Tregs from these mice have reduced suppressive activity and survival.29,30 Coexpression of Helios and Foxp3 in murine CD4+ Tconvs increases the Treg transcriptional signature index compared with Foxp3 alone.31 Furthermore, Helios is required to mediate CD8+ Treg function.29 For these reasons, we hypothesized that ectopic expression of Helios with FOXP3 would generate optimal CD4+ and CD8+ eTreg-mediated immunosuppression.

Here, we report that human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated from the peripheral blood can be genetically modified to express high levels of FOXP3 and Helios. We generated eTregs that coexpressed FOXP3 with the following 2 endogenous splice variants of Helios found in human nTregs32,33: full-length Helios (Hel-FL) and a shorter form, Δ3B Helios (Hel-Δ3B). The addition of Hel-FL to FOXP3 was able to convey increased immunosuppressive properties to both CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs in vitro, and eTregs expressing Hel-FL and FOXP3 were the most effective at immunosuppression in vivo in a xenogeneic GVHD model.

Methods

Isolation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Blood was collected from healthy adult volunteers under signed informed consent with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated via Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) density centrifugation with SepMate tubes (STEMCELL Technologies Inc.).

Construction of retroviral vectors and production of retroviral particles

Retroviral constructs were generated to express complementary DNA (cDNA) encoding FOXP3, Hel-FL, or Hel-Δ3B. The NCBI Reference Sequences for FOXP3, Hel-FL, and Hel-Δ3B are NM_014009.3, NM_016260.2, and NM_001079526.1, respectively. The SFG retroviral vector, RDF, and pEQPAM3 retroviral packaging plasmids were generously donated by Malcom Brenner (Baylor College of Medicine). The cDNAs were cloned into the SFG vector via Gibson assembly.34 Multiple genes were linked in frame with a picornavirus 2A ribosomal skip peptide.35 The FOXP3 construct contains truncated CD19 (ΔCD19) cDNA, and the Hel-FL and Hel-Δ3B contains truncated CD34 (ΔCD34) cDNA. The NCBI Reference Sequences for CD19 and CD34 are NM_001178098.1 and NM_001025109.1. The ΔCD19 and ΔCD34 sequences only contain the signal peptide, extracellular and transmembrane regions. ΔCD19 and ΔCD34 alone vectors were generated as negative controls. FOXP3, ΔCD19, and ΔCD34 were codon optimized via Invitrogen GeneArt Gene Synthesis (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before being cloned into the SFG vector. Hel-FL and Hel-Δ3B cDNA sequences were not altered before cloning. Viral particles were generated by transfecting HEK 293T cells with SFG vectors containing genes of interest, retroviral packaging vectors, and FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega). Viral supernatants were collected 2 and 3 days after transfection and stored at −80°C until use.

Activation and transduction of human T cells

Human T cells were activated in Aim V medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 2% human AB serum (Bio-Techne) (complete media). Then, 3 × 106 PBMCs at 106/mL were stimulated with 2 µg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3 (OKT3; Bio X Cell) and anti-CD28 (9.3; Bio X Cell). After 2 days of activation, complete medium was supplemented with 200 U/mL of recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2) (PeproTech). Cells were passed every 2 to 3 days at 1 to 2 × 106 cells/mL in complete medium supplemented with rhIL-2 (200 U/mL). Five to 6 days postactivation, T cells were transduced with viral supernatants containing ΔCD34 vectors. Allowing cells to expand for 5 to 6 days increased the starting T-cell number an average of twofold. Non-tissue culture 6-well plates were coated in RetroNectin (Takara Bio Inc.) at 20 µg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline per manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 1.5 mL of viral supernatant per well was bound to RetroNectin-coated plates by centrifuging plates for 2 hours at 2000g at 32°C. Viral supernatant was removed, and 1.5 mL of viral supernatant and 2.5 to 3 × 106 T cells in complete medium with rhIL-2 at 106 cells/mL were added to each well. Transduced cells were positively selected 2 days posttransduction with anti-human CD34 CELLection magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Beads were allowed to dissociate and removed via magnet 2 days later, and cells were transduced (without restimulation) with viral supernatants containing ΔCD19 vectors. Transduced cells were positively collected 2 to 3 days later with CELLection Biotin Binder Kit beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coated with biotinylated anti-human CD19 antibody (HIB19; BioLegend). Beads were removed 2 days later and used in assays up to 10 days after the last transduction. FOXP3 and Helios were transduced on separate vectors because Helios downregulated expression of genes on the same vector (including ΔCD34) (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 1). Sequential transduction was also optimal for transduction efficiency.

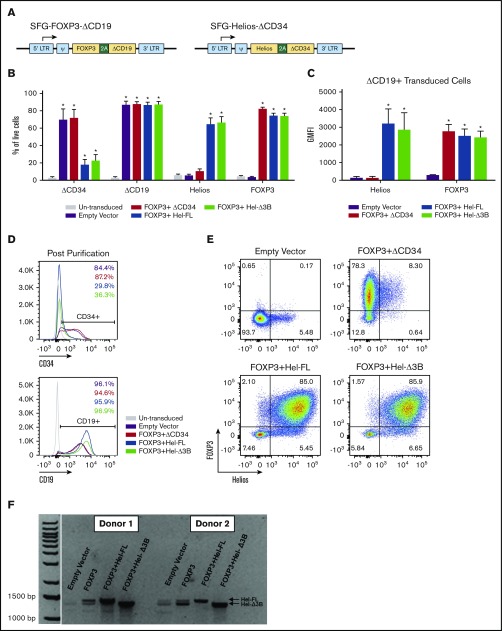

Figure 1.

Generation of human eTregs by transduction with FOXP3 and/or Helios. (A) Illustration of SFG retroviral vector containing genes of interest and transduction surface markers. (B-E) Transduction marker (ΔCD34 and ΔCD19), Helios, and FOXP3 protein expression in eTregs was assessed via surface and intracellular transcription factor staining and flow cytometry. Cells were assessed after the second transduction and magnetic bead purification for CD19. Graphs represent a summary of the percentage of eTregs positive for ΔCD34, ΔCD19, FOXP3, and Helios of total live cells (B) and geometric mean fluorescent intensity (GMFI) of FOXP3 and Helios of transduced cells gated on ΔCD19 expression (C); n = 3 to 9, and 6 different donors. Histograms and dot plots are representative figures of ΔCD34 and ΔCD19 expression following the second transduction and CD19 bead purification (D) and FOXP3 and Helios expression in ΔCD19+ transduced cells (E). (F) Representative figure of Helios messenger RNA expression assessed via real-time polymerase chain reaction and visualized via gel electrophoresis.*P ≤ .05 compared with no eTregs based on a 1-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA was converted to cDNA by using the TaqMan High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed by using the following primers:

F: 5′TGATGGCTATATAACGTGTGACAA3′, R: 5′CTCACACTTGAAGGCCCTAATC3′.

Xenogeneic murine GVHD model

All animal studies were approved by the KUMC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. NOD-SCIDIL-2Rγnull (NSG) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and bred at KUMC under specific pathogen-free conditions.

NSG mice (8-12 weeks old) of both sexes received 1.5 Gy of whole-body irradiation. The next day, the mice were injected retro-orbitally with 107 human PBMCs, 107 PBMCs with 5 × 106 eTregs (all cells from the same donor), or phosphate-buffered saline. Mice were clinically scored with the GVHD scoring system established by Cooke et al36 and euthanized at a score of 7 (graphed as a 7 for the remainder of the experiment) or at 42 days postinjection. The researcher assessing score was blinded to the treatment of each mouse.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with various combinations of the following anti-human antibodies: CD3-APC-Cy7, CD4-PE-Cy7, CD4-eFluor-610, CD8-Alexa Fluor (AF) 488, CD8-Brilliant Violet (BV) 785, CD19-BV421, CD34-BV605, CD39-BV 510, CD25- PerCPCy-5.5, CD127-BV650, CD73-APC-Cy7, CCR4-PE-Cy7, GITR-PE-Cy5, CTLA-4-PE, and CD62L-AF700 (BioLegend). Intracellular transcription factor staining was performed by using the FOXP3 Staining Buffer kit (eBioscience) with anti-human FOXP3-PE, anti-human Helios-AF647, or anti-Helios-BV421 (BioLegend). Samples were run on an LSRII (Becton Dickinson) or Attune NxT (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Activation-induced cell death assay

Cells were resuspended at a concentration of 106 cells/mL in complete media. Then, 2 × 105 cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 µg/mL OKT3) and anti-CD28 (1 µg/mL 9.3) for 2, 4, or 6 days. Cells were stained with Zombie Green Fixable Viability Dye and Annexin V PE (BioLegend) and assessed for cell death via flow cytometry.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Two × 105 cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 µg/mL OKT3) and anti-CD28 (1 µg/mL 9.3) for 6 hours in the presence of Golgi Stop (Becton Dickinson) and Brefeldin A (MilliporeSigma). Cells were stained with extracellular antibodies and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (MilliporeSigma), permeabilized with permeabilization buffer from the FOXP3 Staining Buffer kit (eBioscience), and stained with the following antibodies: anti-human IL-2-FITC, anti-human interferon-γ–Pacific Blue, anti-human IL-10-AF647 or anti-human-IL-21 AF647, anti-human IL-4-PE-Cyanine-7, and anti-human IL-17A BV605 (BioLegend).

Suppression assay

Autologous T cells were isolated from PBMCs by using a T-cell enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies Inc.) and labeled with the Cell Proliferation Dye eFluor670 (eBioscience). T cells were cocultured with each eTreg cell strain at a 1:1 ratio with or without stimulation at 5 × 105 cells/mL. Cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 coated DYNAL Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (1:10 bead:target cell ratio). After 96 hours, cells were stained with Zombie Green Fixable Viability Dye (BioLegend), and target cell proliferation was assayed via flow cytometry. Percent suppression was calculated by the following equation: [(percent responder proliferation alone) – (percent responder proliferation with transduced cells)]/(percent responder proliferation alone) × 100.

RNA sequencing

FOXP3–ΔCD19+ΔCD34, FOXP3–ΔCD19+Hel-FL–ΔCD34, and FOXP3–ΔCD19+Hel-Δ3B–ΔCD34 cells were generated with PBMCs from 3 different donors. Cells were collected 5 days after the second transduction, and CD4+ and CD8+ cells were isolated via flow cytometry–assisted cell sorting on a BD FACS Aria III (BD Biosciences). RNA was isolated by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). TruSeq stranded messenger RNA sequencing libraries were performed by using the Illumina TruSeq and NuGEN sample preparation kits (Illumina). Paired-end RNA sequencing data were generated by using a NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System (Illumina).

Adaptor removal was performed by cutadapt,37 and quality control was done with FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). Samples were aligned to human genome (hg38) with RSEM38 and bowtie2,39 and transcript counts were obtained. Using the Bioconductor package “edgeR,”40 data were normalized according to library size, and genes with low expression were filtered out. Genes were retained if their count per million (cpm) value was larger than 1 for at least 2 samples of the 18 considered in this study. After filtering low/nonexpressed genes, 13 955 remained for subsequent statistical analysis (supplemental Table 1).

Genes were further filtered with differential expression by taking the top 2000 genes with the lowest false discovery rate and then further restricted to genes with an expression change that was the same direction in all 3 donors. These filtered lists were made for each donor and comparison, and the cpm gene counts were used to conduct a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) with the GSEA version 3.0 software (Broad Institute) (supplemental Table 2). Enrichment in the KEGG pathway gene sets (c2.cp.kegg.v6.2.symbols.gmt) was used to identify and visualize significantly enriched pathways.41,42

To examine Treg-related gene expression, heat maps were generated based on the cpm values. Two lists of Treg genes were generated based on comparisons of Tconvs vs Tregs by Miyara et al,15 Mold et al,43 and Bonacci et al,44 referred to as the “up gene list” and the “down gene list.” From the gene expression comparisons data, genes were analyzed that were present in the up or down Treg gene lists and had a nominal, uncorrected P < .05. Genes were then selected if they exhibited the expected expression pattern; that is, all 3 subjects were upregulated in an up-gene comparison or vice versa. Finally, the 2 comparisons were merged into 1 heat map. For each cell in the heat map, the difference of cpm values was calculated between 2 strains of cell for 1 subject and divided by the average cpm value of that gene in all 3 subjects.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software) and the R statistical programming language (http://r-progject.org). Data reported at each time point for GVHD score are an average of the scores of the mice left alive and the last scores and weights of any deceased mice in each group. Mann-Whitney U tests were done to compare GVHD scores at each time point. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for analysis of Kaplan-Meier curves. Differences between groups were compared via Mann-Whitney U tests. Differences between groups with data normalized to a control were compared by using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, which paired data points within separate experiments. One-tailed analysis was used because hypotheses were 1 tailed (1 direction). P ≤ .05 was considered significant. Results show mean ± standard error of the mean unless indicated otherwise.

Results

Generation of human eTregs via retroviral transduction of FOXP3 and Helios

We generated human eTregs that expressed both FOXP3 and Helios with a dual vector transduction system. A dual vector system was used because a single tricistronic vector resulted in reduced expression of FOXP3 in Helios-expressing cells (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 1). In addition, we transduced total T cells rather than purified CD4+ T cells19 to reduce selection steps in eTreg production. T cells in both mice and humans express 2 isoforms of Helios, Hel-FL, and the shorter isoform lacking half of the 3rd exon (Hel-Δ3B), although little is known about the functional differences between these splice variants.32,33 Thus, we transduced either Hel-FL or Hel-Δ3B with a truncated CD34 marker (ΔCD34) and FOXP3 with a truncated CD19 marker (ΔCD19) into T cells purified from peripheral blood to obtain a mixed population of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that highly expressed both Helios and FOXP3 (supplemental Figure 2). Although ΔCD34 expression was downregulated in transduced cells with Helios (Figure 1D), there was still higher expression of Helios compared with an empty vector control (Figure 1E). The transduced isoform of Helios was the predominant splice variant of Helios expressed in each eTreg (Figure 1F).

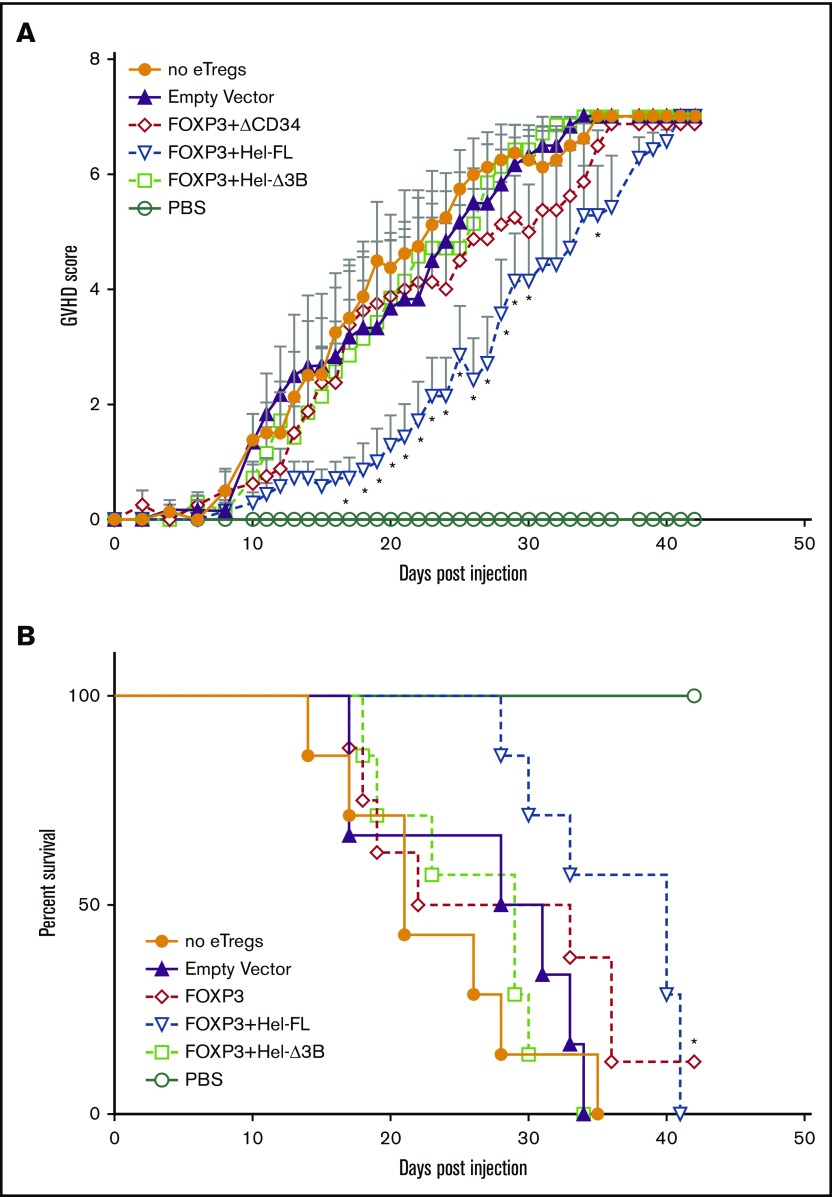

FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs delay disease in a xenogeneic GVHD model

To assess the suppressive capacity of each eTreg strain, we used a xenogeneic GVHD model in which sublethally irradiated NSG mice were injected with human PBMCs without or with each eTreg cell strain. Injected eTregs had comparable CD4:CD8 ratios across all groups (supplemental Figure 3). Treatment with FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs significantly delayed GVHD progression compared with mice injected with PBMCs alone (Figure 2A). In addition, FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs significantly improved overall survival compared with mice injected with PBMCs only (Figure 2B). In contrast, the FOXP3 or FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B eTregs did not delay GVHD or affect overall survival.

Figure 2.

FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs delay disease progression in a xenogeneic GVHD murine model. NSG mice aged 8 to 12 weeks were sublethally irradiated. The next day, the mice were injected retro-orbitally with 107 human PBMCs alone (n = 8), with 107 human PBMCs + 5 × 106 empty vector control cells (n = 6), 107 human PBMCs + 5 × 106 FOXP3 eTregs (n = 8), 107 human PBMCs + 5 × 106 FOXP3+HEL-FL eTregs (n = 7), or 107 human PBMC + 5 × 106 FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B eTregs (n = 7). (A) GVHD score. *P ≤ .05 compared with no eTregs based on a 1-tailed Mann-Whitney U test for each time point. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of survival. Death was marked when the GVHD score was ≥7. The data shown are the aggregated data from 5 separate experiments that used T cells from 4 different donors. *P ≤ .05 compared with no eTregs as determined by using the log-rank test. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

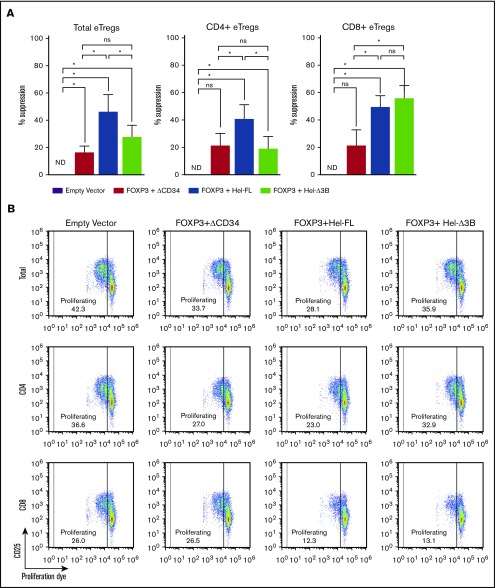

Hel-FL and Hel-Δ3B coexpression with FOXP3 differentially regulate CD4+ and CD8+ eTreg suppression

To determine why the FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs were best at suppressing GVHD, we first assessed the ability of each eTreg strain to suppress T-cell proliferation in vitro. In addition to the total eTregs, we purified and analyzed the suppressive capability of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the eTreg strains separately. Hel-FL expression increased the ability of both total and CD4+ eTregs to suppress the proliferation of naive T cells in this assay (Figure 3; supplemental Figures 4-6). However, both FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B similarly increased the suppressive capability of CD8+ eTregs. These data show that there is a differential requirement for Helios isoform expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for the enhancement of suppressive function of FOXP3-expressing eTregs.

Figure 3.

FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B differentially mediate CD4+and CD8+eTreg suppression of T-cell proliferation. Labeled autologous target Tconv cells were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio with each eTreg cell strain or empty vector control cells with no stimulation or stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 coated beads. After 96 hours, proliferation of target cells (CD19– eFluor670+) was assayed via flow cytometry. (A) Percent suppression for each eTreg cell strain. Cells were plated as follows: 5 × 104 target Tconvs alone, 5 × 104 target Tconvs + 5 × 104 empty vector control cells, 5 × 104 target Tconvs + 5 × 104 FOXP3 eTregs, 5 × 104 target Tconvs + 5 × 104 FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs, or 5 × 104 target Tconvs + 5 × 104 FOXP3+ Hel-Δ3B eTregs. Tregs were either both CD4+ and CD8+ (n = 5 for each condition), CD4+ only (n = 7), or CD8+ only (n = 6). T cells from 4 different donors were used. Negative percent suppression was plotted as 0% suppression. (B) Representative dot plots of responder cell proliferation 96 hours after coculture with eTregs or empty vector control. *P ≤ .05 in each comparison based on a 1-tailed Wilcoxon test. ND, not detectable; ns, not statistically significant.

Helios expression reduces eTreg proliferation and survival

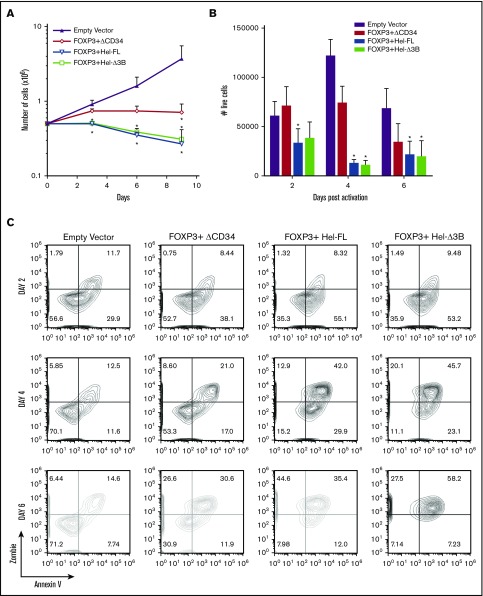

To determine whether the greater suppressive function of the Helios-expressing eTregs was due to enhanced eTreg survival, we compared the proliferation and survival of the eTreg cell strains in vitro. FOXP3 expression reduced proliferation over time, and the addition of either isoform of Helios further reduced proliferation and/or survival (Figure 4A). There was also an increase in activation-induced cell death in all 3 eTreg cell strains, with more death observed in both the Helios-expressing eTregs (Figure 4B-C). Interestingly, Helios expression alone did not significantly affect proliferation (supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 4.

Expression of FOXP3, FOXP3+Hel-FL, and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B reduces cell expansion and survival. (A) Cell counts of eTregs growing in IL-2–supplemented media over 9 days. n = 4 for each group from 4 different donors. *P ≤ .05 compared with empty vector control based on a 1-tailed Mann-Whitney U test for each time point. (B) Numbers of live (Zombie Green and Annexin V negative) eTregs after stimulation for 2, 4, and 6 days with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 plate-bound antibody. Cells were plated as follows: 2 × 105 empty vector control cells (n = 5), 2 × 105 FOXP3 eTregs (n = 5), 2 × 105 FOXP3+HEL-FL eTregs (n = 6), or 2 × 105 FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B eTregs (n = 6). T cells from 4 to 6 different donors were used. *P ≤ .05 compared with empty vector control based on a 1-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. (C) Representative contour plots of activation-induced cell death in eTregs or empty vector control cells after stimulation for 2, 4, and 6 days.

Hel-FL and Hel-Δ3B differentially affect gene expression in FOXP3-expressing human T cells

In addition to no observable difference in cell survival between FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B eTregs, we detected no differences in the expression of the Treg markers CD25, CD73, or CCR4, or secretion of interferon-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, or IL-17A between these cell strains (supplemental Figures 8-10). Therefore, to determine how these cell strains were different, we performed RNA sequencing (supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

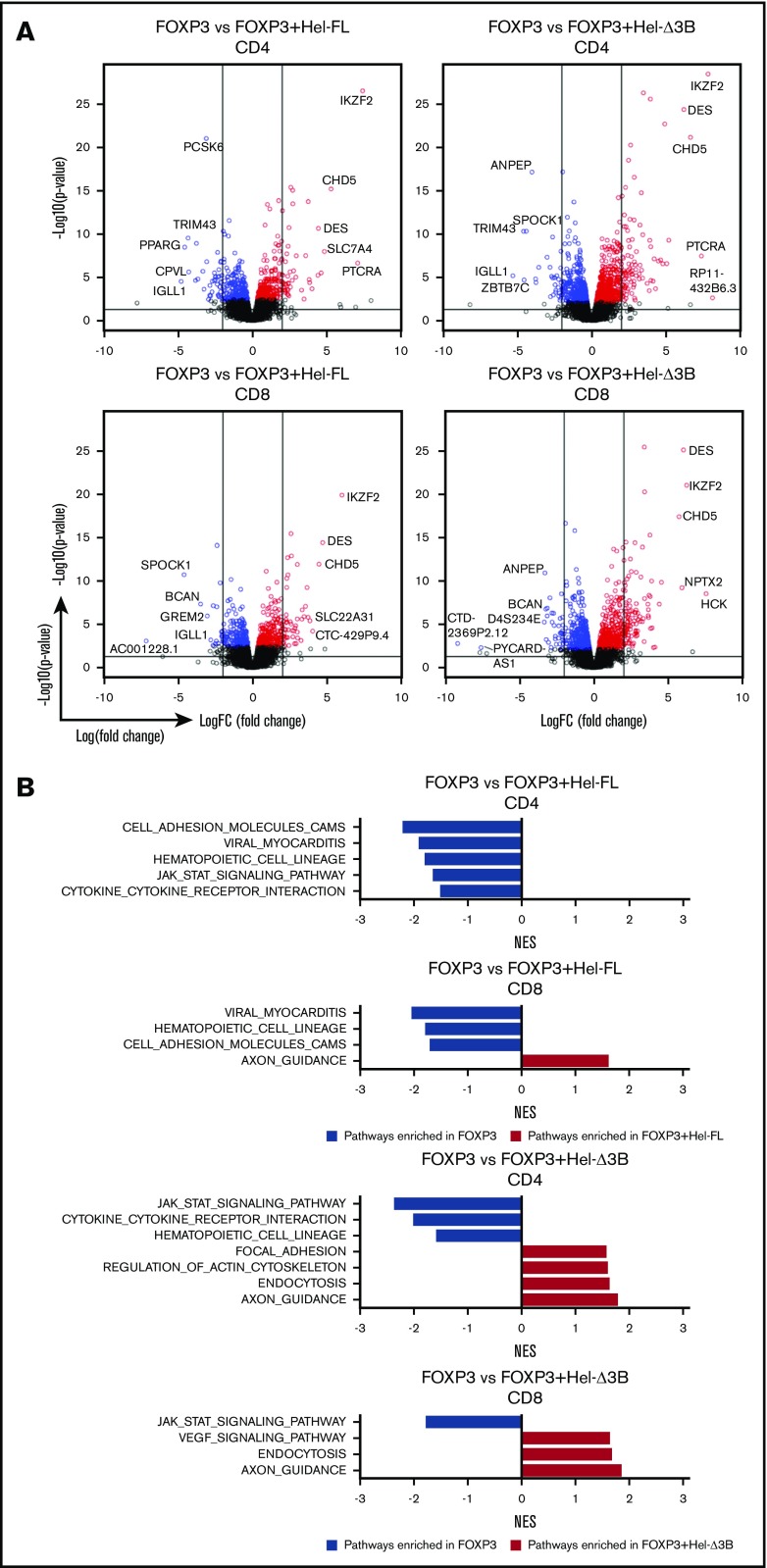

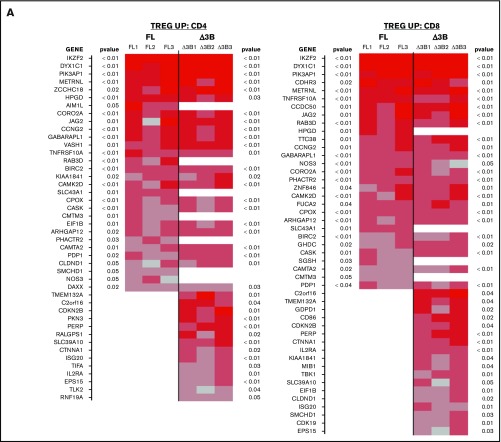

Adding either isoform of Helios to FOXP3-expressing CD4+ or CD8+ eTregs significantly changed gene expression and altered the KEGG pathways enriched compared with FOXP3 alone (Figure 5). FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B eTregs had the least transcriptional differences (Figure 6A). However, FOXP3+Hel-FL induced enrichment in different KEGG pathways more than FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B in both CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs (Figure 6B). Three of these pathways were enriched by Hel-FL in both CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs; these were the p53 signaling, cell adhesion molecule, and cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathways. Of note, however, there were differences in the genes that were changed in these common pathways between CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs (supplemental Figure 11).

Figure 5.

Hel-FL or Hel-Δ3B coexpression with FOXP3 alters gene expression and pathway enrichment in CD4+or CD8+eTregs compared with FOXP3 alone. All comparisons in this figure use FOXP3 eTregs as the baseline for comparison of CD4+ or CD8+ eTregs as indicated. (A) Volcano plots depicting gene expression differences between the cell strains. Within the volcano plots, genes were colored if they had a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤0.1. Blue denotes downregulation, and red represents upregulation. The 2 vertical lines represent logFC= −2 and logFC= 2. The horizontal line presents –log10(0.05). (B) Summary of normalized enrichment scores (NES) of KEGG pathways with P ≤ .05 that were enriched in the comparison of two eTreg cell strains indicated after GSEA. Blue bars are pathways enriched in the baseline eTregs, and red bars are pathways enriched in eTregs being compared.

Figure 6.

FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B mediates different gene transcription and pathway enrichment in CD4+and CD8+eTregs compared with FOXP3+Hel-FL. All comparisons in this figure use FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs as the baseline for comparison, either CD4+ or CD8+ as indicated. (A) Volcano plots depicting gene changes. Within the volcano plots, genes were colored if they had an FDR ≤0.1. Blue denotes downregulation, and red represents upregulation in the indicated comparison. The 2 vertical lines represent logFC= −2 and logFC = 2. The horizontal line presents –log10(0.05). (B) Summary of normalized enrichment scores (NES) of KEGG pathways with P ≤ .05 that were enriched compared with two eTreg cell strains after GSEA. Blue bars are pathways that are more downregulated in the Hel-Δ3B–expressing cell line, and red bars are pathways that are more upregulated in the Hel-Δ3B cell line, compared with the HEL-FL–expressing cell line.

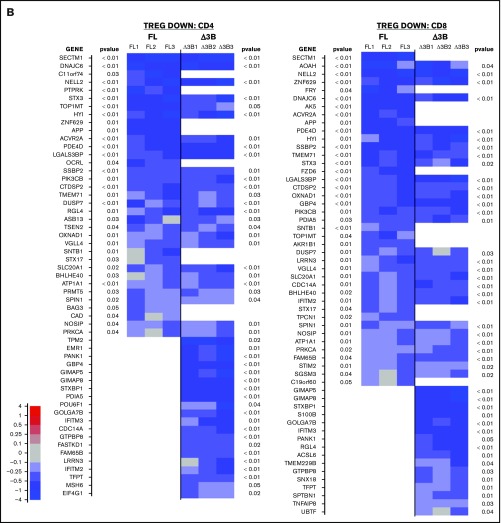

We also compared the genes expressed in our eTreg strains vs a “Treg signature” that we generated from a list of gene changes observed in previous comparisons between human Tconvs and Tregs.15,43,44 Coexpression of Hel-FL or Hel-Δ3B with FOXP3 generated cells with more “Treg signature”–like gene expression compared with FOXP3 alone (Figure 7). However, the FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B eTregs had a gene expression pattern most similar to this “Treg signature.” This was true for both CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs. In addition, there were many Treg genes whose expression was differently affected by the coexpression of Hel-FL or Hel-Δ3B with FOXP3 in both CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs.

Figure 7.

Hel-FL or Hel-Δ3B coexpression with FOXP3 mediates different gene transcription of Treg signature genes in CD4+and CD8+eTregs. Heat maps comparing expression of Treg signature genes that are upregulated in Tregs (TREG UP) (A) or downregulated in Tregs (TREG DOWN) (B) compared with Tconv. Each heat map shows differential expression of genes in each of the 3 donors for FOXP3 vs FOXP3+Hel-FL (FL, donors FL1-FL3) and FOXP3 vs FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B (Δ3B, donors Δ3B1-Δ3B1) in both CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs as indicated. We first identified the subset of genes that had a nominal, uncorrected P < .05 in each indicated eTreg comparison based on change in expression of the TREG UP and TREG DOWN genes. Indicated P values are based on average change in gene expression for each eTreg comparison. For each cell in the heat map, the difference of cpm values between 2 strains of cell for 1 subject was calculated and divided by the average cpm value of that gene in all 3 subjects.

Discussion

The current article describes that overexpression of Hel-FL along with FOXP3 in total human T cells converts these T cells into CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs with immunosuppressive properties. We recognize that transduction efficiency will need to be optimized to translate this work to the clinic. One approach would be to transduce cells 2 to 3 days after activation when cells are more actively dividing. We showed that treatment with these FOXP3+Hel-FL human eTregs was able to delay disease in a xenogeneic GVHD model, whereas treatment with FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B or FOXP3 eTregs was not. Similarly, we found that both CD4+ and CD8+ FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs had the most suppressive capacity in vitro compared with FOXP3 alone. There were no measurable differences in survival, Treg marker expression, or cytokine production between FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3 eTregs. Thus, we performed RNA sequencing and revealed that there was a significant change in gene expression between FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs compared with FOXP3 alone. These genes are involved in immune pathways, including cell adhesion molecules, JAK/STAT signaling, and Treg-related genes. Changes in transcription were expected, as ectopic expression of Helios and FOXP3 in mouse Tconvs mediated expression of different Treg signature genes.22,31 However, the changes we observed in the human cells by Helios expression were different from those observed in mouse T cells. Further studies will be needed to determine which specific genes and pathways altered by Hel-FL expression are responsible for the observed changes in human eTreg function.

Although Helios has been described as a key Treg transcription factor for many years, its function in Tregs is still being defined. Experiments using Treg-specific Helios-deficient mice showed that Helios plays a major role in mediating both CD4+ and CD8+ mouse Treg function and survival.29,30 In contrast, we found that in human eTregs, Helios expression reduced Treg survival but enhanced Treg suppressive function. This scenario correlates with the Helios+ subset of human CD4+ Tregs that have improved stability in proinflammatory environments compared with Helios– CD4+ Tregs.23-28

We found that both Hel-FL and Hel-Δ3B coexpression with FOXP3 changed gene expression compared with FOXP3 alone, but there were changes that were unique to each isoform of Helios. We also found that coexpression of these 2 isoforms differentially affected the suppressive function of FOXP3-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs. FOXP3+Hel-FL expression improved CD4+ eTreg suppressive activity, whereas FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B expression did not. However, FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B did improve suppressive activity of CD8+ eTregs to a similar degree as FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs. Correlation of the gene changes in FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B with our functional studies reveal molecular mechanisms required to convey immunosuppressive properties to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Our RNA sequencing and GSEA data showed that FOXP3+Hel-FL CD4+ eTregs had increased gene enrichment in p53 signaling and cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction but decreased gene enrichment in cell adhesion molecules compared with FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B CD4+ eTregs. Consistent with these data, p53 signaling is important for CD4+ Treg induction in mice.45 The various cytokine receptors that were upregulated on FOXP3+Hel-FL CD4+ eTregs included the chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR6, which have been shown to be expressed on endogenous human Tregs,46 where these receptors drive immune cell trafficking to sites of inflammation.47-52 The differences we observed in cell adhesion molecule expression between FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B CD4+ eTregs could be linked to T-cell immunosuppressive function, although further studies are needed. Thus, the changes we found in these 3 KEGG pathways likely explain why FOXP3+Hel-FL CD4+ eTregs were more effective at suppressing in vivo and in vitro than FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B CD4+ eTregs. However, this theory will have to be directly tested in future studies.

FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B and FOX+Hel-FLCD8+ eTregs had similar differences in KEGG pathway expression compared with FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B and FOX+Hel-FL CD4+ eTregs, but unlike with the CD4+ eTregs, these CD8+ eTreg cell strains suppressed equally well in vitro. Further examination revealed there were differences in the specific genes that were changed in the common pathways altered in FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B compared with FOX+Hel-FL CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs. Thus, the specific gene expression differences in these pathways that were unique to the CD4+ eTregs could identify the genes important in mediating T-cell suppressive activity.

We found that both CD4+ and CD8+ FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B had a higher Treg signature compared with FOXP3+Hel-FL eTregs based on the number of genes that were differentially expressed in our Treg signature gene lists. However, based on the functional differences between FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B CD4+ eTregs, it is the genes that are differentially expressed between these 2 eTreg cell strains that are critical to CD4+ T-cell immunosuppressive function rather than the number of genes changed. Similarly, the gene expression differences between the FOXP3+Hel-FL and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B CD8+ eTregs are not critical to CD8+ T-cell immunosuppression, as these 2 cell strains suppress at a similar level.

Taken together, our findings indicate that the endogenous isoforms of Helios play different roles in CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs. Hel-Δ3B lacks half an exon in a zinc finger domain, which affects its ability to bind DNA. Thus, differences between the effect of FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B overexpression in CD4+ vs CD8+ T cells likely arises from epigenetic differences between the cell subsets and promoter accessibility. Another example of Ikaros family members playing different roles in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is the critical role of Ikaros in CD8+, but not CD4+, T-cell development.53 Investigating the differences between FOXP3, FOXP3+Hel-FL, and FOXP3+Hel-Δ3B CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs will help define which signaling pathways are critical for CD4+ and CD8+ Treg function.

In conclusion, our data show that ectopic expression of Hel-FL along with FOXP3 in human T cells results in the generation of immunosuppressive CD4+ and CD8+ eTregs. We describe differential roles for the 2 endogenous isoforms of Helios in mediating suppressive function in CD4+ and CD8+. These new findings define new roles for endogenous Helios splice variants in both CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs. These findings not only provide insight into the role of Helios and FOXP3 coexpression in Treg function but could improve current human eTreg generation protocols and increase the potential for eTregs to be used in the clinic.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Clark Bloomer and the University of Kansas School of Medicine Genomics Core for their assistance in performing the RNA sequencing.

The authors acknowledge the Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory (supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [NIH], National Institute of General Medical Sciences Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence grant P30 GM103326 and National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA168524), as well as the Bioinformatics Core (supported in part by the NIH, National Institute of General Medical Sciences IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence award P20 GM103428) and the Biostatistics and Informatics Shared Resource (NIH, National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA168524). This work was partially funded by the Tripp Family Foundation (A.S. and T.M.Y.) and the 2017 Biomedical Research Training Program (A.S.)

Footnotes

RNA sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE135452).

For original data, please contact mmarkiewicz@kumc.edu.

Authorship

Contribution: A.S., R.T.F., and T.M.Y. designed and planned the experiments with input from M.A.M.; A.S. and K.L.K. performed the experiments; D.P. and D.C.K. performed the RNA sequencing statistical analyses; A.S., T.M.Y., and M.A.M. analyzed and discussed the data; R.T.F. provided strategic guidance throughout the project; A.S., R.T.F., and M.A.M. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.A.M. is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Global Services for topics unrelated to this work. M.A.M., A.S., R.T.F., and T.M.Y. have filed a patent provisional based on the work in this publication. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mary A. Markiewicz, Department of Microbiology, Molecular Genetics, and Immunology, University of Kansas Medical Center, 3901 Rainbow Blvd, MS 3029, Kansas City, KS 66160; e-mail: mmarkiewicz@kumc.edu.

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155(3):1151-1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacchetta R, Passerini L, Gambineri E, et al. Defective regulatory and effector T cell functions in patients with FOXP3 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1713-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):68-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):20-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holderried TA, Lang PA, Kim HJ, Cantor H. Genetic disruption of CD8+ Treg activity enhances the immune response to viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(52):21089-21094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HJ, Verbinnen B, Tang X, Lu L, Cantor H. Inhibition of follicular T-helper cells by CD8(+) regulatory T cells is essential for self tolerance. Nature. 2010;467(7313):328-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(14):3921-3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trzonkowski P, Dukat-Mazurek A, Bieniaszewska M, et al. Treatment of graft-versus-host disease with naturally occurring T regulatory cells. BioDrugs. 2013;27(6):605-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunstein CG, Miller JS, McKenna DH, et al. Umbilical cord blood-derived T regulatory cells to prevent GVHD: kinetics, toxicity profile, and clinical effect. Blood. 2016;127(8):1044-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bluestone JA, Buckner JH, Fitch M, et al. Type 1 diabetes immunotherapy using polyclonal regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(315):315ra189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez-Fueyo A, Whitehouse G, Grageda N, et al. Applicability, safety, and biological activity of regulatory T cell therapy in liver transplantation [published online ahead of print 12 November 2019]. Am J Transplant. doi:10.1111/ajt.15700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caruso A, Licenziati S, Corulli M, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of activation markers on stimulated T cells and their correlation with cell proliferation. Cytometry. 1997;27(1):71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann P, Boeld TJ, Eder R, et al. Loss of FOXP3 expression in natural human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells upon repetitive in vitro stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(4):1088-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann P, Eder R, Boeld TJ, et al. Only the CD45RA+ subpopulation of CD4+CD25high T cells gives rise to homogeneous regulatory T-cell lines upon in vitro expansion. Blood. 2006;108(13):4260-4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30(6):899-911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Jeker LT, et al. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(9):1000-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingrao D, Majdoul S, Seye AK, Galy A, Fenard D. Concurrent measures of fusion and transduction efficiency of primary CD34+ cells with human immunodeficiency virus 1-based lentiviral vectors reveal different effects of transduction enhancers. Hum Gene Ther Methods. 2014;25(1):48-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright GP, Notley CA, Xue SA, et al. Adoptive therapy with redirected primary regulatory T cells results in antigen-specific suppression of arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(45):19078-19083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allan SE, Alstad AN, Merindol N, et al. Generation of potent and stable human CD4+ T regulatory cells by activation-independent expression of FOXP3. Mol Ther. 2008;16(1):194-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299(5609):1057-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao J, Chen C, Zeng L, Li L, Li Z, Xu K. Engineered regulatory T cells prevent graft-versus-host disease while sparing the graft-versus-leukemia effect after bone marrow transplantation. Leuk Res. 2010;34(10):1374-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill JA, Feuerer M, Tash K, et al. Foxp3 transcription-factor-dependent and -independent regulation of the regulatory T cell transcriptional signature. Immunity. 2007;27(5):786-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3433-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Himmel ME, MacDonald KG, Garcia RV, Steiner TS, Levings MK. Helios+ and Helios- cells coexist within the natural FOXP3+ T regulatory cell subset in humans. J Immunol. 2013;190(5):2001-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugita K, Hanakawa S, Honda T, et al. Generation of Helios reporter mice and an evaluation of the suppressive capacity of Helios(+) regulatory T cells in vitro. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24(7):554-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma MD, Huang L, Choi JH, et al. An inherently bifunctional subset of Foxp3+ T helper cells is controlled by the transcription factor eos. Immunity. 2013;38(5):998-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dijke IE, Hoeppli RE, Ellis T, et al. Discarded human thymus is a novel source of stable and long-lived therapeutic regulatory T cells. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(1):58-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bin Dhuban K, d’Hennezel E, Nashi E, et al. Coexpression of TIGIT and FCRL3 identifies Helios+ human memory regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2015;194(8):3687-3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Barnitz RA, Kreslavsky T, et al. Stable inhibitory activity of regulatory T cells requires the transcription factor Helios. Science. 2015;350(6258):334-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebastian M, Lopez-Ocasio M, Metidji A, Rieder SA, Shevach EM, Thornton AM. Helios controls a limited subset of regulatory T cell functions. J Immunol. 2016;196(1):144-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu W, Ergun A, Lu T, et al. A multiply redundant genetic switch “locks in” the transcriptional signature of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(10):972-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asanuma S, Yamagishi M, Kawanami K, et al. Adult T-cell leukemia cells are characterized by abnormalities of Helios expression that promote T cell growth. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(8):1097-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell JL, Seng A, Yankee TM. Expression and splicing of Ikaros family members in murine and human thymocytes. Mol Immunol. 2017;87:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA III, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):343-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma P, Yan F, Doronina VA, Escuin-Ordinas H, Ryan MD, Brown JD. 2A peptides provide distinct solutions to driving stop-carry on translational recoding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(7):3143-3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooke KR, Kobzik L, Martin TR, et al. An experimental model of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after bone marrow transplantation: I. The roles of minor H antigens and endotoxin. Blood. 1996;88(8):3230-3239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17(1):10-12.

- 38.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(1):323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545-15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mold JE, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Burt TD, et al. Fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells give rise to distinct T cell lineages in humans. Science. 2010;330(6011):1695-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonacci B, Edwards B, Jia S, et al. Requirements for growth and IL-10 expression of highly purified human T regulatory cells. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(5):1118-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawashima H, Takatori H, Suzuki K, et al. Tumor suppressor p53 inhibits systemic autoimmune diseases by inducing regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2013;191(7):3614-3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim HW, Broxmeyer HE, Kim CH. Regulation of trafficking receptor expression in human forkhead box P3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177(2):840-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butcher MJ, Wu CI, Waseem T, Galkina EV. CXCR6 regulates the recruitment of pro-inflammatory IL-17A-producing T cells into atherosclerotic aortas. Int Immunol. 2016;28(5):255-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan MC, Goedegebuure PS, Belt BA, et al. Disruption of CCR5-dependent homing of regulatory T cells inhibits tumor growth in a murine model of pancreatic cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182(3):1746-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan IA, Thomas SY, Moretto MM, et al. CCR5 is essential for NK cell trafficking and host survival following Toxoplasma gondii infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(6):e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang X, Shimaoka T, Kojo S, et al. Cutting edge: critical role of CXCL16/CXCR6 in NKT cell trafficking in allograft tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2051-2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gottrand G, Courau T, Thomas-Vaslin V, et al. Regulatory T-cell development and function are impaired in mice lacking membrane expression of full length intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Immunology. 2015;146(4):657-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deane JA, Abeynaike LD, Norman MU, et al. Endogenous regulatory T cells adhere in inflamed dermal vessels via ICAM-1: association with regulation of effector leukocyte adhesion. J Immunol. 2012;188(5):2179-2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Brien S, Thomas RM, Wertheim GB, Zhang F, Shen H, Wells AD. Ikaros imposes a barrier to CD8+ T cell differentiation by restricting autocrine IL-2 production. J Immunol. 2014;192(11):5118-5129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.