Key Points

The K666N mutation of SF3B1 has distinct clinicopathologic features in MDS.

The K666N mutation of SF3B1 has a distinct RNA splicing profile.

Introduction

SF3B1 is commonly mutated in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs).1 The mutations are hotspot, mostly missense substitutions, with K700E being the most frequent. They create a neomorphic spliceosome that missplices RNA and alters the proteome, although how this drives MDS is unclear.2-5 SF3B1MUT is strongly associated with MDS with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS), which has a relatively slower rate of progression.6 However, outcomes are heterogeneous in lower-risk MDS, so identifying additional features of SF3B1MUT MDS that are associated with disease progression could improve the management and understanding of disease. Here, we report that the K666N hotspot of SF3B1 is associated with increased progression of MDS and distinct RNA splicing.

Methods

For comparison of mutation hotspot frequencies, SF3B1 mutations from MDS and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cases were collected from 3 sources: (1) patients seen at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, and the MDS and MPN Centre at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, (2) data directly deposited into the Project Genie database of the cBio Cancer Genomics Portal (http://genie.cbioportal.org/),7 and (3) manual extraction from 67 published studies (supplemental References). SF3B1 mutations were included if they were annotated with the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms, because this was the informative clinical feature most commonly provided in publications. Individual SF3B1 mutations occurring in clonal hematopoiesis were gathered from 21 additional studies (supplemental References). Because there was heterogeneity in the exons of the SF3B1 gene sequenced in different studies, we only included mutations in exons 14 and 15, which were sequenced in all studies and contain the majority of SF3B1 mutations. Therefore, other minor mutation hotspots, such as E592 and G742, could not be compared with this analysis. For clinicopathologic characterizations, retrospective patient data from each local cancer center were curated from all MDS patients with SF3B1 mutation, and statistical comparisons were made using the Student t test (for Revised International Prognostic Scoring System [IPSS-R] and blood counts), the χ2 test (for ring sideroblast [RS] categories), or the Mantel-Cox test (for survival). Higher IPSS-R patients were defined as those in high or very high IPSS-R risk categories, and lower IPSS-R patients were defined as those in very low, low, or intermediate risk categories. Cox regression analysis was performed on lower IPSS-R patients. For comutation analysis, studies were also heterogeneous with regard to the additional genes that they sequenced; therefore, patient data were included if at least a minimum gene list had been sequenced, which represented a compromise between maximum sample inclusion and maximum gene inclusion. For MDS-RS and MDS with excess blasts (MDS-EB), the list included SF3B1, TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1, JAK2, CBL, EZH2, RUNX1, TP53, IDH2, IDH1, U2AF1, SRSF2, NRAS, and NPM1. For AML, it included SF3B1, RUNX1, FLT3, NPM1, GATA2, NRAS, KRAS, IDH1, IDH2, DMT3A, ASXL1, TET2, KIT, TP53, and EZH2. For statistical comparisons between disease subtype distribution for individual hotspot mutations and for comutation analyses, the Fisher’s exact test was used. For analysis of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data from Darman et al,2 sequence files were obtained from National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE72790. Aberrant junctions that had been identified by the investigators as being upregulated in SF3B1K700E cells were inspected for relative expression in SF3B1H662Q and SF3B1K666N cells, and the candidate differentially expressed junctions COPS2, SUPV3L1, and RRN3 were selected for further analysis. The SF3B1H662Q and SF3B1WT Nalm6 isogenic cell lines were obtained from Horizon Discovery; the HNT34, MUTZ, and CMLT1 cell lines were from DSMZ; and KG1 cells were a gift from R. A. Casero (Johns Hopkins University). All cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640/20% fetal bovine serum, and MUTZ3 cells were supplemented with 10 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR were performed on complementary DNA synthesized from extracted total RNA using standard methods.

Inclusion and analysis of all deidentified patient data were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, and the MDS and MPN Center at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Results and discussion

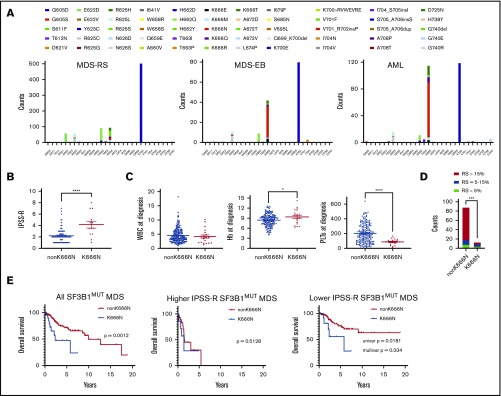

In several reported AML cohorts, SF3B1MUT cases had frequent mutations at the hotspot K666 (supplemental Figure 1),8-10 which are less common in MDS. Because this might suggest that K666 mutations correlate with MDS progression, we systematically evaluated this possibility by comparing >1200 SF3B1MUT cases: 841 cases of MDS-RS, 150 cases of MDS-EB, and 294 cases of AML (Figure 1A). The mutation distribution showed that K666 was indeed differentially partitioned across diseases, but the effect was driven primarily by 1 mutation, K666N, which increased from 1.5% in MDS-RS to 21% in MDS-EB to 28% in AML (P < 1.1E−15 for both). Other K666 mutations were not enriched (K666E, K666M, K666Q), were modestly enriched (K666T, 2.3-4.8%; P < .05), or were de-enriched (K666R, 4.5-1.0%; P < .01) between MDS-RS and AML. Thus, among SF3B1 mutations, the K666N hotspot is distinctly associated with high-risk MDS and AML.

Figure 1.

Clinicopathologic features of SF3B1K666N MDS. (A) The distribution of publicly available mutations in exons 14 and 15 of SF3B1 for MDS-RS, MDS-EB, and AML show enrichment of SF3B1K666N with increasing disease severity. Notably, E622D is absent in MDS-EB and AML, in contrast to MDS-RS. (B) In our cohorts, compared with patients with other SF3B1 mutations, SF3B1K666N patients exhibited higher IPSS-R scores. (C) SF3B1K666N patients had similar white blood cells counts (WBC; left panel), slightly higher hemoglobin levels (Hb; center panel), and lower platelets (PLTs; right panel). (D) SF3B1K666N patients had decreased RSs. (E) Among all SF3B1MUT patients, survival was shorter in those with SF3B1K666N (left panel). Survival was equally poor in both groups with higher IPSS-R MDS (middle panel), but lower IPSS-R SF3B1K666N patients had shorter survival (right panel). Univariate (Mantel-Cox) and multivariate (Cox regression including IPSS-R categories) P values are shown. *P < .05, ****P < .0001, 2-tailed Student t test. ***P < .001, χ2 test.

To go beyond population frequencies, we studied 214 SF3B1MUT MDS patients, 21 with SF3B1K666N, from 3 institutions (supplemental Tables 1-3). As above, 52% of K666N patients had MDS-EB, compared with 12% of non-K666N patients (P = 4.0E−5). SF3B1K666N also showed higher IPSS-R scores (Figure 1B), partly as a result of lower platelets (Figure 1C). In contrast, white blood cell count was similar between groups, and hemoglobin was modestly higher in K666N (Figure 1C). RSs, although present in most cases, were lower in K666N (Figure 1D). This was consistent with the still-low-but-slightly-higher-than-in-MDS-RS frequency of SF3B1K666N in MDS subtypes without RSs (supplemental Figure 2A). The SF3B1MUT variant allele fraction was similar between groups (supplemental Figure 3). We then assessed outcomes, which showed shorter overall survival (OS) for SF3B1K666N patients in cohorts 1 and 2 and a trend for cohort 3 (supplemental Figure 3). With cohorts combined, outcomes were markedly worse for K666N, with median OS of 2.3 years vs 10 years for non-K666N (P = .0012) (Figure 1E). Stratification showed that, although outcomes were similarly poor for higher IPSS-R category patients in both groups, SF3B1K666N had shorter OS in the lower IPSS-R category patients (Figure 1E). In fact, covariate analysis that included IPSS-R categories showed that K666N had independent negative prognostic value in lower IPSS-R category patients (Figure 1E).

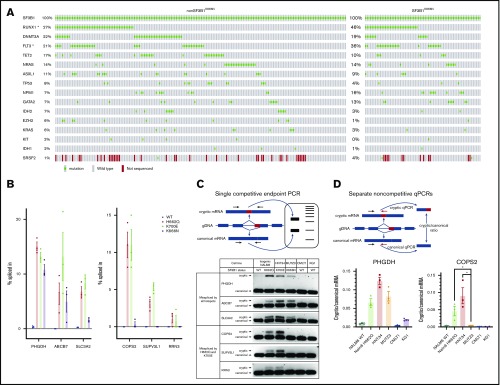

We next examined comutations in SF3B1MUT patients. In AML, comutation distribution was similar between groups, although K666N patients had more RUNX1 and FLT3 mutations (Figure 2A). Of note, SF3B1K666N was frequent in primary and secondary AML (supplemental Figure 2B-C). Comutation frequencies were also comparable between groups for MDS-RS and MDS-EB, although 1 notable difference was that 4 of 10 K666N MDS-RS cases had mutations in the spliceosome gene SRSF2, in contrast to 0.4% (2/471) of non-K666N (supplemental Figure 5). In 2 cases, SF3B1 and SRSF2 variable allele frequencies were available and relatively high, suggesting that they were mutated in the same cells (supplemental Table 4). Because different spliceosome mutations generally show mutual exclusivity,11 this suggests that SF3B1K666N is especially permissive of, or cooperative with, SRSF2 mutations. That said, SRSF2MUT enrichment was not seen in SF3B1K666N MDS-EB or AML, so the implications of this association in the smaller number of SF3B1K666N MDS-RS cases are not clear. Overall, these data show that K666N and non-K666N MDS/AML have similar comutations, and it is unlikely that the distinct clinicopathologic features of SF3B1K666N are driven solely by comutational differences.

Figure 2.

Biologic features of the K666N mutation in SF3B1. (A) Comutation distribution of SF3B1MUT AML patients shows a similar genetic landscape between K666N and other SF3B1 mutations, although RUNX1 and FLT3 mutations were higher in SF3B1K666N patients. SRSF2 was also included, despite not being sequenced in all samples, because of its increased comutation in SF3B1K666N MDS-RS (supplemental Figure 3). *P < .05, Fisher’s exact test. (B) Analysis of RNA-seq performed on isogenic Nalm6 cells by Darman et al shows that missplicing of some junctions is increased in all mutant cells (left panel), whereas others are increased in cells with K700E and H662Q, but not K666N, mutations (right panel). (C) Use of a single competitive end point PCR (upper panel) to validate distinct missplicing in independent cell populations with SF3B1 mutation, including SF3B1K700E HNT34 AML cells, SF3B1K666N MUTZ3 AML cells, wild-type CMLT1 and KG1 leukemia cells, and isogenic Nalm6 controls (lower panel). (D) Use of separate noncompetitive quantitative PCRs (qPCRs; upper panel) to further validate distinct missplicing in PHGDH (lower left panel) and COPS2 (lower right panel). *P < .05, Student t test.

To consider potential mechanisms, we next investigated RNA splicing. We first examined publicly available RNA-seq data generated by Darman et al on Nalm-6 isogenic cell knock-ins of the K700E, H662Q, and K666N mutations.2 Most aberrant splice junctions had increased expression in all mutant cells, but we identified cryptic junctions increased in cells with K700E and H662Q, but not K666N, mutations (Figure 2B). Because such differences could arise by chance within RNA-seq or from differences in single knock-in clones unrelated to the introduced mutations, we validated this pattern in independent cells. Isoform-competitive end point PCR in AML with naturally arising SF3B1 mutations showed increased missplicing of PHGDH, ABCB7, and SLC3A2 in all mutant cells, whereas missplicing of COPS2, IPO7, and RRN3 was detected in K700E and H662Q, but not in K666N, cells (Figure 2C). Further validation with isoform-separate quantitative PCR was done on PHGDH and COPS2 (Figure 2D). These data indicate that SF3B1K666N can induce patterns of RNA missplicing distinct from other SF3B1 mutations.

These findings have several important implications. First, the distinctive features of SF3B1K666N described here indicate that not all SF3B1 mutations are equal. Previous studies have classified them together, understandably, given their many shared characteristics, but hotspot-specific differences likely permeate these analyses.12-14 We propose that studies of SF3B1MUT patients should consider individual mutation identities. Given the divergent enrichment in AML of K666N compared even with other mutations at K666, these identities should be the precise amino acid changes, not solely grouping mutations by the SF3B1 residue affected. A second implication is that individual SF3B1 mutations can be associated with different clinical outcomes. SF3B1 mutations are generally considered favorable in MDS, but our data on SF3B1K666N show that this is not always the case. At the same time, other hotspots were de-enriched in advanced disease, most notably E622D (Figure 1A), suggesting that some hotspots may contribute to especially indolent MDS. Distinct hotspots may also be important in the outcomes of other disease states, such as SF3B1MUT clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, where K666N is, interestingly, rather frequent (supplemental Figure 6). Future longitudinal studies of individuals with clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential could determine how clones with distinct SF3B1 hotspots differentially give rise to symptomatic disease. Third, our data showing distinct RNA missplicing in cells with different SF3B1 mutations suggest a potential mechanism by which these hotspots produce divergent disease consequences. Additional studies are warranted to determine whether particular missplicing events, or the lack thereof, mediate hotspot-specific phenotypes. It is also notable that certain residues, like K666, but not K700 or H662, are involved in the tertiary structure of SF3B1,15 suggesting structural mechanisms that may underlie splicing differences. Lastly, our data show that the K666N hotspot mutation in SF3B1 is associated with high-risk MDS, transformation to AML, thrombocytopenia, decreased RSs, and decreased OS. These results suggest that SF3B1K666N MDS patients may need more aggressive management than patients with other SF3B1 mutations, particularly in lower IPSS-R category disease. Although additional patient cohorts will help to extend these findings, we nonetheless submit here that, in SF3B1MUT MDS, K666N is the devil.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Lilly Innovation Fellowship Award, the Department of Defense (grant W81XWH-17-1-0035), and AbbVie (all to W.B.D.); and National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants K08 HL136894 (L.P.G.) and K08 HL127269 (G.G.).

Footnotes

Data sharing requests should be sent to W. Brian Dalton (wdalton2@jhmi.edu).

Authorship

Contribution: W.B.D. and A.E.D. designed research; W.B.D., E.H., L.P., and A.E.D. performed research; W.B.D., E.H., L.P., C.D.G., J.D., B.L., Z.X., L.P.G., G.G., I.G., B.D.S, M.J.L., and A.E.D. collected data; W.B.D., E.H., C.D.G., J.D., L.P.G., and A.E.D. analyzed and interpreted data; and W.B.D. and A.E.D. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: W. Brian Dalton, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, 1650 Orleans St, CRBI Room 285, Baltimore, MD 21231; e-mail: wdalton2@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):241-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darman RB, Seiler M, Agrawal AA, et al. Cancer-associated SF3B1 hotspot mutations induce cryptic 3′ splice site selection through use of a different branch point. Cell Rep. 2015;13(5):1033-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsafadi S, Houy A, Battistella A, et al. Cancer-associated SF3B1 mutations affect alternative splicing by promoting alternative branchpoint usage. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalton WB, Helmenstine E, Walsh N, et al. Hotspot SF3B1 mutations induce metabolic reprogramming and vulnerability to serine deprivation. J Clin Invest. 2019;130(11):4708-4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberante FG, Lappin K, Barros EM, et al. Altered splicing and cytoplasmic levels of tRNA synthetases in SF3B1-mutant myelodysplastic syndromes as a therapeutic vulnerability. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, et al. ; Chronic Myeloid Disorders Working Group of the International Cancer Genome Consortium . Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1384-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consortium T; AACR Project GENIE Consortium . AACR Project GENIE: powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(8):818-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(23):2209-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metzeler KH, Herold T, Rothenberg-Thurley M, et al. ; AMLCG Study Group . Spectrum and prognostic relevance of driver gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016;128(5):686-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2018;562(7728):526-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011;478(7367):64-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malcovati L, Papaemmanuil E, Bowen DT, et al. ; Chronic Myeloid Disorders Working Group of the International Cancer Genome Consortium and of the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative . Clinical significance of SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118(24):6239-6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patnaik MM, Lasho TL, Hodnefield JM, et al. SF3B1 mutations are prevalent in myelodysplastic syndromes with ring sideroblasts but do not hold independent prognostic value. Blood. 2012;119(2):569-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damm F, Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, et al. ; Groupe Francophone des Myélodysplasies . Mutations affecting mRNA splicing define distinct clinical phenotypes and correlate with patient outcome in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;119(14):3211-3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cretu C, Schmitzová J, Ponce-Salvatierra A, et al. Molecular architecture of SF3b and structural consequences of its cancer-related mutations. Mol Cell. 2016;64(2):307-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.