Abstract

Background

We examined how often new serious safety signals were identified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration within the first 2 years after approval for new molecular entities (NMEs) for treatment of cancer that required specific regulatory actions described here.

Methods

We identified, for all NMEs approved for treatment of cancer or malignant hematology indications between 2010 and 2016, substantial safety‐related changes within the first 2 years after approval, which included a new Boxed Warning or Warning and Precaution; requirement for (or modification of existing) Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS); and withdrawal from the market because of safety concerns.

Results

Fifty‐five NMEs were approved between 2010 and 2016: 32 (58%) under regular approval (RA) and 23 (42%) under accelerated approval (AA). Of these 55 NMEs, 9 (16%) had substantial safety‐related changes after approval. Across all 55 NMEs, one was temporarily withdrawn from the market for safety reasons (1.8%); one (1.8%) required a new REMS; nine required labeling revisions—new Boxed Warnings were required for two NMEs (3.6%), and new Warnings and Precautions subsections were required for eight (14.6%). One drug (ponatinib) was responsible for several of the substantial safety‐related changes (withdrawal, REMS, Boxed Warnings). One of 32 NMEs approved under RA required a new Warning and Precaution, whereas 7 of 23 NMEs approved under AA had substantial safety‐related changes in the first 2 years after approval.

Conclusion

Based on our analysis we conclude that although there was a greater incidence of substantial safety‐related changes to AA drugs versus RA drugs, the majority of these were changes to the Warnings and Precautions and did not substantially alter the benefit‐risk profile of the drug.

Implications for Practice

The majority of new cancer drugs (84%) approved in the U.S. do not have new substantial safety information being added to the label within the first 2 years of approval. Unprecedented efficacy seen in contemporary cancer drug development has led to early availability of effective cancer therapies based on large effects in smaller populations. More limited premarket safety data require diligent postmarketing safety surveillance as we continue to learn and update drug labeling throughout the product lifecycle.

Keywords: FDA approval, Approval safety signals, Accelerated approval

Short abstract

An increasing number of oncology drugs are approved under the FDA Accelerated Approval Program. This article examines new molecular entity approvals and evaluates subsequent changes in recommendations for use of these drugs.

Introduction

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves new drugs and biologics (subsequently referred to under the collective term drugs) based on the results of adequate and well controlled clinical trials that demonstrate substantial evidence of safety and effectiveness or substantial evidence of an effect reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit 1. The regular approval (RA) pathway was the main pathway used for oncologic drug approvals until the introduction of the accelerated approval (AA) pathway in 1992 during the HIV crisis. Since its introduction as an expedited pathway to approval of drugs that treat serious or life‐threatening conditions and offer an advantage over available therapy, an increasing number of oncology drugs have been approved under AA.

Between December 11, 1992, and May 31, 2017, the FDA Office of Hematology and Oncology Products (OHOP) approved 64 drugs for treatment of cancer or hematologic malignancies under AA for 93 new indications 2. Accelerated approvals are based on surrogate endpoints that are reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit or on an intermediate clinical endpoint that can be measured earlier than clinical benefit endpoints such as overall survival. Although earlier endpoints allow for smaller and more efficient clinical trials, there may be less information available regarding the safety data of the drug at the time of approval compared with new molecular entities (NMEs) approved under regular approval 2. One analysis of novel drugs approved between 2010 and 2016 stated that those drugs receiving accelerated approval had a higher chance of detecting new postapproval safety signals (incidence rate ratio, 2.20; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15–4.21; p = .02) 3. Oncology drugs represented a minority of the approvals studied (21%).

The primary goal of this analysis was to examine oncology NME approvals between 2010 and 2016 and evaluate new substantial safety‐related changes, defined in this analysis as a new Boxed Warning or Warning and Precaution; requirement for (or modification of existing) Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS); or withdrawal from the market because of safety concerns, identified in the first 2 years after approval for drugs receiving accelerated approval compared with regular approval. In general, these safety‐related regulatory actions are taken when the adverse reaction is so serious it is essential to consider when assessing the risk and benefit of using the drug (Boxed Warning), there are serious or otherwise clinically significant adverse reactions that have implications for prescribing decisions or patient management (Warnings and Precautions), and a drug safety program (e.g., information communicated to and/or required activities to be undertaken by one of more participants to dispense, prescribe, or take the medication) is required for drugs with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks (REMS).

Materials and Methods

We identified all NMEs approved by OHOP in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research between 2010 and 2016 using an internal database. Cellular and gene therapies, vaccines, and nonmalignant hematology or supportive care products were not included in this analysis.

The following information was captured: the pathway used for the initial approval (RA vs. AA), characteristics of the trials that supported initial approval (randomized vs. single arm), type of randomized control (active vs. placebo), and the size of the safety database supporting initial approval. We then reviewed the products for substantial safety‐related changes defined as requiring the following regulatory actions within the first 2 years after approval: the addition of a new Boxed Warning or new Warnings and Precautions added to the approved prescribing information (product label), requirement for (or modification of existing) REMS, and withdrawal from the market because of safety concerns. We chose the 2‐year postapproval period to reflect data that may otherwise have been obtained if a larger trial had been conducted for the original approval, because one study showed that the median time to establishment of confirmatory clinical benefit for drugs approved via the AA pathway was 3.4 years (range, 0.5–12.6 years) 2. Identification of postapproval changes to the original FDA‐approved product labeling were identified using product labeling posted on the Web site Drugs@FDA: FDA‐Approved Drug Products 4. Safety‐related product withdrawals were identified using FDA safety communications posted on FDA's Web site Drug Safety Communications 5. In addition, FDA's Web site Drug Safety‐Related Labeling Changes 6 and FDA approval announcements posted on FDA's Web site Hematology/Oncology (Cancer) Approvals & Safety Notifications were used in adjunct to extract the information outlined above 7.

The number of patients in the safety database supporting approval of NMEs was identified using the introductory paragraph that details the characteristics of the safety database (patients exposed to the NME) in Section 6 of the approved prescribing information. When such information was missing in this section of the label, the number of treated patients in the investigational arm of the common adverse event table(s) was used to determine the safety database at initial approval.

Results

Between 2010 and 2016, there were 55 novel anticancer drugs approved by OHOP; of these 55 NMEs, 23 (42%) were approved under the provisions of AA and 32 (58%) were approved under RA. Among the 55 NMEs, 9 drugs (16%) had new safety signals added within 2 years of approval. Among the 23 receiving AA, 8 (35%) NMEs had substantial safety‐related changes within 2 years of approval. Among the 32 granted RA, one (3%) NME had substantial safety‐related changes within 2 years of approval.

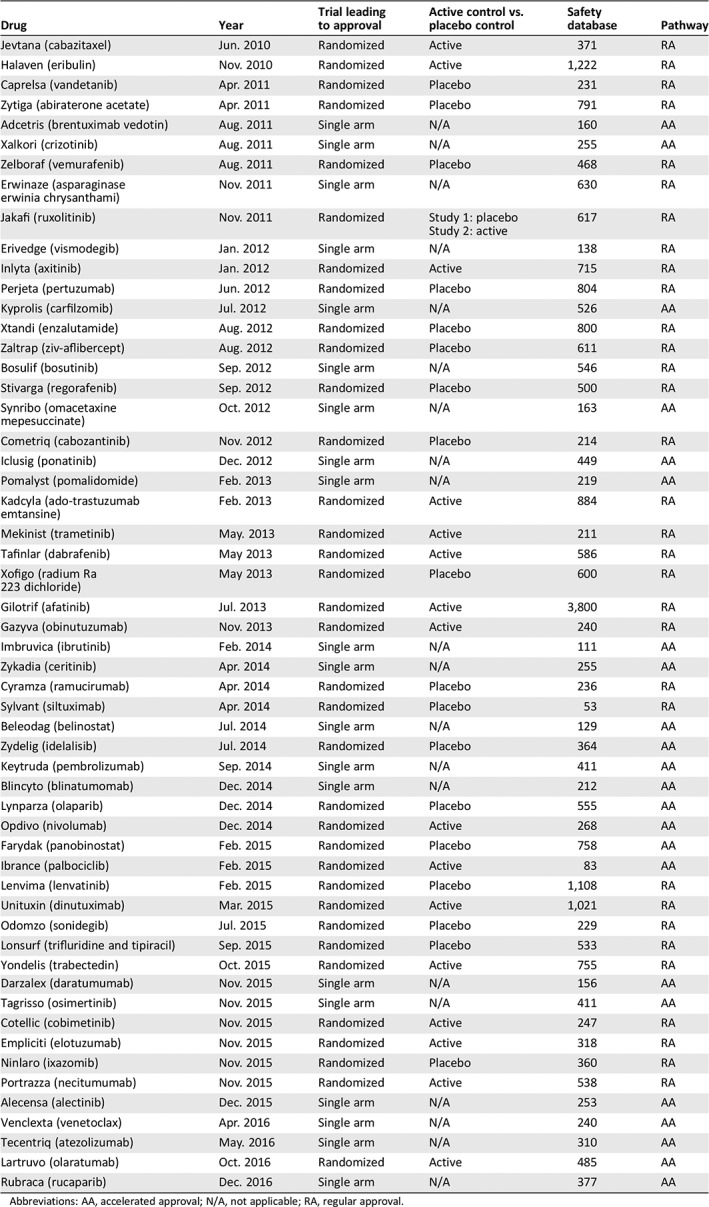

Approval Characteristics

For 23 NMEs approved under AA, 17 (74%) approvals relied on single‐arm trials, and 6 (26%) relied on randomized trials. Among the six NMEs approved under AA based on randomized trials, three had an active comparator arm, and three had a placebo comparator arm. In contrast, for the 32 NMEs approved under RA, 3 (9%) relied on single‐arm trials, and 29 (91%) relied on randomized trials. Among the 29 NMEs approved under RA based on randomized trials, 14 had an active comparator arm, and 15 had a placebo comparator arm (Table 1). Among the drugs that had the safety information of interest added, all drugs were approved on the basis of a single‐arm trial (AA pathway), except vemurafenib, which was approved on the basis of a randomized clinical trial through the RA pathway. Among the drugs that did not have these changes, 74% were randomized trials, and 26% were single‐arm trial design.

Table 1.

2010–2016 new molecular entity approvals: approval characteristics

| Drug | Year | Trial leading to approval | Active control vs. placebo control | Safety database | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jevtana (cabazitaxel) | Jun. 2010 | Randomized | Active | 371 | RA |

| Halaven (eribulin) | Nov. 2010 | Randomized | Active | 1,222 | RA |

| Caprelsa (vandetanib) | Apr. 2011 | Randomized | Placebo | 231 | RA |

| Zytiga (abiraterone acetate) | Apr. 2011 | Randomized | Placebo | 791 | RA |

| Adcetris (brentuximab vedotin) | Aug. 2011 | Single arm | N/A | 160 | AA |

| Xalkori (crizotinib) | Aug. 2011 | Single arm | N/A | 255 | AA |

| Zelboraf (vemurafenib) | Aug. 2011 | Randomized | Placebo | 468 | RA |

| Erwinaze (asparaginase erwinia chrysanthami) | Nov. 2011 | Single arm | N/A | 630 | RA |

| Jakafi (ruxolitinib) | Nov. 2011 | Randomized |

Study 1: placebo Study 2: active |

617 | RA |

| Erivedge (vismodegib) | Jan. 2012 | Single arm | N/A | 138 | RA |

| Inlyta (axitinib) | Jan. 2012 | Randomized | Active | 715 | RA |

| Perjeta (pertuzumab) | Jun. 2012 | Randomized | Placebo | 804 | RA |

| Kyprolis (carfilzomib) | Jul. 2012 | Single arm | N/A | 526 | AA |

| Xtandi (enzalutamide) | Aug. 2012 | Randomized | Placebo | 800 | RA |

| Zaltrap (ziv‐aflibercept) | Aug. 2012 | Randomized | Placebo | 611 | RA |

| Bosulif (bosutinib) | Sep. 2012 | Single arm | N/A | 546 | RA |

| Stivarga (regorafenib) | Sep. 2012 | Randomized | Placebo | 500 | RA |

| Synribo (omacetaxine mepesuccinate) | Oct. 2012 | Single arm | N/A | 163 | AA |

| Cometriq (cabozantinib) | Nov. 2012 | Randomized | Placebo | 214 | RA |

| Iclusig (ponatinib) | Dec. 2012 | Single arm | N/A | 449 | AA |

| Pomalyst (pomalidomide) | Feb. 2013 | Single arm | N/A | 219 | AA |

| Kadcyla (ado‐trastuzumab emtansine) | Feb. 2013 | Randomized | Active | 884 | RA |

| Mekinist (trametinib) | May. 2013 | Randomized | Active | 211 | RA |

| Tafinlar (dabrafenib) | May 2013 | Randomized | Active | 586 | RA |

| Xofigo (radium Ra 223 dichloride) | May 2013 | Randomized | Placebo | 600 | RA |

| Gilotrif (afatinib) | Jul. 2013 | Randomized | Active | 3,800 | RA |

| Gazyva (obinutuzumab) | Nov. 2013 | Randomized | Active | 240 | RA |

| Imbruvica (ibrutinib) | Feb. 2014 | Single arm | N/A | 111 | AA |

| Zykadia (ceritinib) | Apr. 2014 | Single arm | N/A | 255 | AA |

| Cyramza (ramucirumab) | Apr. 2014 | Randomized | Placebo | 236 | RA |

| Sylvant (siltuximab) | Apr. 2014 | Randomized | Placebo | 53 | RA |

| Beleodag (belinostat) | Jul. 2014 | Single arm | N/A | 129 | AA |

| Zydelig (idelalisib) | Jul. 2014 | Randomized | Placebo | 364 | AA |

| Keytruda (pembrolizumab) | Sep. 2014 | Single arm | N/A | 411 | AA |

| Blincyto (blinatumomab) | Dec. 2014 | Single arm | N/A | 212 | AA |

| Lynparza (olaparib) | Dec. 2014 | Randomized | Placebo | 555 | AA |

| Opdivo (nivolumab) | Dec. 2014 | Randomized | Active | 268 | AA |

| Farydak (panobinostat) | Feb. 2015 | Randomized | Placebo | 758 | AA |

| Ibrance (palbociclib) | Feb. 2015 | Randomized | Active | 83 | AA |

| Lenvima (lenvatinib) | Feb. 2015 | Randomized | Placebo | 1,108 | RA |

| Unituxin (dinutuximab) | Mar. 2015 | Randomized | Active | 1,021 | RA |

| Odomzo (sonidegib) | Jul. 2015 | Randomized | Placebo | 229 | RA |

| Lonsurf (trifluridine and tipiracil) | Sep. 2015 | Randomized | Placebo | 533 | RA |

| Yondelis (trabectedin) | Oct. 2015 | Randomized | Active | 755 | RA |

| Darzalex (daratumumab) | Nov. 2015 | Single arm | N/A | 156 | AA |

| Tagrisso (osimertinib) | Nov. 2015 | Single arm | N/A | 411 | AA |

| Cotellic (cobimetinib) | Nov. 2015 | Randomized | Active | 247 | RA |

| Empliciti (elotuzumab) | Nov. 2015 | Randomized | Active | 318 | RA |

| Ninlaro (ixazomib) | Nov. 2015 | Randomized | Placebo | 360 | RA |

| Portrazza (necitumumab) | Nov. 2015 | Randomized | Active | 538 | RA |

| Alecensa (alectinib) | Dec. 2015 | Single arm | N/A | 253 | AA |

| Venclexta (venetoclax) | Apr. 2016 | Single arm | N/A | 240 | AA |

| Tecentriq (atezolizumab) | May. 2016 | Single arm | N/A | 310 | AA |

| Lartruvo (olaratumab) | Oct. 2016 | Randomized | Active | 485 | AA |

| Rubraca (rucaparib) | Dec. 2016 | Single arm | N/A | 377 | AA |

Abbreviations: AA, accelerated approval; N/A, not applicable; RA, regular approval.

Safety Database

The median number of patients in the safety database at the time of approval was 255 NME‐exposed patients (range, 83–758 patients) for NMEs approved under AA and 542 patients (range, 53–3,800 patients) for NMEs approved under RA. Among the drugs that had substantial safety‐related changes approved under the AA pathway, the median was 310 (range, 156–449), compared with the safety database of 468 for the single RA with these safety‐related changes (vemurafenib; Table 1).

Safety‐Related Changes

REMS

One of 55 (2%; 95% CI, 0–9.7) NMEs required the implementation of a REMS within 2 years of approval. The drug that required an addition of REMS was ponatinib, which was approved under AA. Ponatinib was approved on December 14, 2012, temporarily withdrawn from the market in October 2013, and reintroduced to the market in conjunction with REMS, new Boxed Warnings, and a narrowed indication for use on December 20, 2013. The REMS was required because of the risk of serious vascular occlusions, including loss of vision due to blood clots, and occlusion of mesenteric blood vessels, stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease with ischemic necrosis, and other vascular occlusive events.

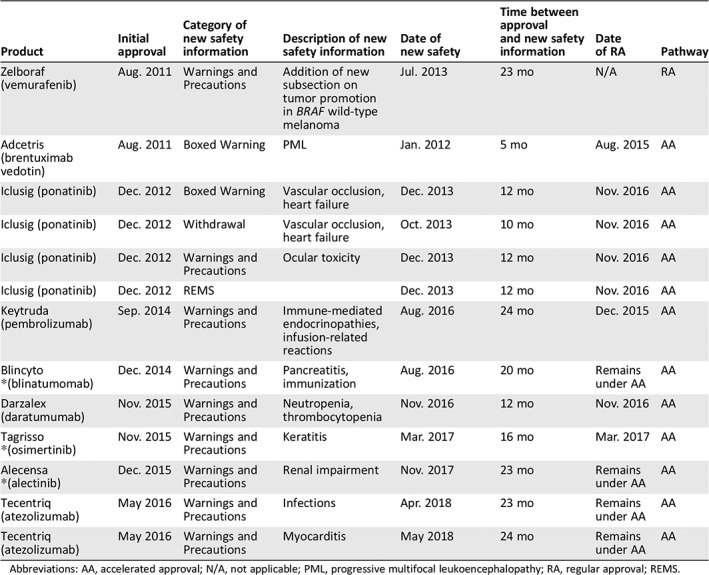

Boxed Warning

The addition of a new Boxed Warning occurred for 2 of the 55 NMEs within 2 years of approval (Table 2); in both cases, the NME was approved under AA for an incidence of 2 of 23 NMEs (8.7%; 95% CI, 1.1–28). Specifically, for ponatinib the previous Boxed Warnings for arterial thrombosis was modified to vascular occlusion, and a new Boxed Warning was added for heart failure, based on an 8% incidence, including fatal events, in December 2013. A new Boxed Warning for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy was added to the brentuximab vedotin label in January 2012.

Table 2.

New safety information for new molecular entities within 2 years of approval

| Product | Initial approval | Category of new safety information | Description of new safety information | Date of new safety | Time between approval and new safety information | Date of RA | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zelboraf (vemurafenib) | Aug. 2011 | Warnings and Precautions | Addition of new subsection on tumor promotion in BRAF wild‐type melanoma | Jul. 2013 | 23 mo | N/A | RA |

| Adcetris (brentuximab vedotin) | Aug. 2011 | Boxed Warning | PML | Jan. 2012 | 5 mo | Aug. 2015 | AA |

| Iclusig (ponatinib) | Dec. 2012 | Boxed Warning | Vascular occlusion, heart failure | Dec. 2013 | 12 mo | Nov. 2016 | AA |

| Iclusig (ponatinib) | Dec. 2012 | Withdrawal | Vascular occlusion, heart failure | Oct. 2013 | 10 mo | Nov. 2016 | AA |

| Iclusig (ponatinib) | Dec. 2012 | Warnings and Precautions | Ocular toxicity | Dec. 2013 | 12 mo | Nov. 2016 | AA |

| Iclusig (ponatinib) | Dec. 2012 | REMS | Dec. 2013 | 12 mo | Nov. 2016 | AA | |

| Keytruda (pembrolizumab) | Sep. 2014 | Warnings and Precautions | Immune‐mediated endocrinopathies, infusion‐related reactions | Aug. 2016 | 24 mo | Dec. 2015 | AA |

| Blincyto *(blinatumomab) | Dec. 2014 | Warnings and Precautions | Pancreatitis, immunization | Aug. 2016 | 20 mo | Remains under AA | AA |

| Darzalex (daratumumab) | Nov. 2015 | Warnings and Precautions | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | Nov. 2016 | 12 mo | Nov. 2016 | AA |

| Tagrisso *(osimertinib) | Nov. 2015 | Warnings and Precautions | Keratitis | Mar. 2017 | 16 mo | Mar. 2017 | AA |

| Alecensa *(alectinib) | Dec. 2015 | Warnings and Precautions | Renal impairment | Nov. 2017 | 23 mo | Remains under AA | AA |

| Tecentriq (atezolizumab) | May 2016 | Warnings and Precautions | Infections | Apr. 2018 | 23 mo | Remains under AA | AA |

| Tecentriq (atezolizumab) | May 2016 | Warnings and Precautions | Myocarditis | May 2018 | 24 mo | Remains under AA | AA |

Abbreviations: AA, accelerated approval; N/A, not applicable; PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; RA, regular approval; REMS.

Withdrawal

Only one drug, ponatinib, was temporarily withdrawn from the market for safety‐related changes described previously. Although the risk of life‐threatening blood clots and severe narrowing of blood vessels was recognized at the time of approval and noted in a Boxed Warning, the scope and frequency of these adverse reactions became more apparent after approval and were not adequately described in the initially approved labeling. Thus, FDA requested that the company voluntarily suspend marketing of ponatinib until improved communication of this risk could be updated and a REMS instituted. These changes were approved on December 20, 2013, and ponatinib was reintroduced to the market with a narrower indication, limited approval to the population with the greatest unmet medical need, and an expanded Boxed Warning (Table 2).

Warning and Precaution

Eight (15%) of the 55 NMEs required the addition of a new Warning and Precaution subsection in the approved prescribing information within 2 years of initial approval. Vemurafenib added a warning on tumor promotion in BRAF wild‐type melanoma. Ponatinib added a new warning on ocular toxicity. Pembrolizumab added a new warning on immune‐mediated endocrinopathies and infusion‐related reactions. Blinatumomab added a new warning on pancreatitis and immunizations. Daratumumab added a new warning on neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Osimertinib added a new warning on keratitis. Alectinib added a new warning on renal impairment. Lastly, atezolizumab added a new a warning on infections and myocarditis. For drugs approved under AA, 7 of 23 (30.4%; 95% CI, 13.2–52.9) added new Warnings and Precautions, and for those approved under RA, 1 of 32 (3.1%; 95% CI, 0.1–16.2) added new Warnings and Precautions (Table 2).

Discussion

When new serious safety signals are identified after approval, FDA can communicate these risks through modification of FDA‐approved product labeling (e.g., addition of new Boxed Warnings or Warnings and Precautions, narrowing of an indication) and FDA‐issued safety communications and alerts. FDA may also require a REMS or require withdrawal of drugs from the market if serious risks are identified that outweigh the benefits of the drug. Our analysis shows that the majority of new drugs (84%) regardless of approval pathway did not have substantial safety‐related changes within the first 2 years of approval.

Among the nine NME drugs for which these postapproval safety‐related changes occurred, eight drugs added new Warnings and Precautions, two drugs added new Boxed Warnings, one drug was temporarily withdrawn, and one REMS was added. One drug, ponatinib, accounted for four types of safety‐related labeling changes: withdrawal, addition of Boxed Warning, addition of new Warnings and Precautions, and REMS addition.

Numerically, there were more Warnings and Precautions added for drugs approved than other more substantial postapproval safety‐related changes such as REMS, Boxed Warnings, and withdrawals. Warnings and Precautions are defined in FDA Guidance for Industry as “adverse reactions … that are serious or are otherwise clinically significant because they have implications for prescribing decisions or for patient management” 8. New Warnings and Precautions that were identified in this subset of approvals such as keratitis, ocular toxicity, renal impairment, etc., are serious risks that need to be communicated to the prescriber for monitoring and supportive care. However, with the exception of ponatinib, these findings did not significantly affect the overall favorable benefit‐risk profile of the drugs in the context of the nature of the serious and life‐threatening diseases they treat. The change in the benefit‐risk profile for ponatinib resulted in a narrowing of the indicated population, but no changes in the originally approved population were made for the other nine drugs.

The observation of having more Warnings and Precautions added to products approved under accelerated approval compared with regular approval is likely due to multiple factors, including the quantity and duration of patient follow‐up. Overall, our data reveal that AA safety databases are approximately half as large as RA applications, reducing the number of patients at risk. In addition, there is often a shorter duration of follow‐up for AA studies compared with RA. With increasing experience of a drug after marketing authorization, with more randomized controlled studies and single‐arm studies in broader populations as well as real‐world use, the possibility of new safety signals requiring communication in product labeling increases 9. FDA has generally accepted this risk of marketing authorization with more limited safety information as the natural tradeoff for earlier availability of promising anticancer agents.

Because of the serious and life‐threatening nature of most cancers and the high unmet need, rapid access in exchange for smaller safety databases may be justified for many oncology indications. The AA pathway has been successful in providing earlier access to effective anticancer therapies, with a median time from AA to completion of the postmarketing trial verifying benefit of 3.4 years 2 and only 5% of accelerated approvals withdrawn for failure to verify benefit. Had the larger randomized postmarketing trial been required prior to marketing the drug, patients would have had to wait an additional median of 3.4 years to access effective anticancer therapy. Regardless of approval pathway, the initial FDA approval of an NME marks the beginning of the cancer therapy's postmarketing life cycle, and safety signals may be identified as more is learned. Robust postmarketing surveillance mechanisms are in place at FDA and by the sponsor to detect these signals early and communicate new safety information to the public. FDA also encourages providers and the public to submit postmarketing adverse event information to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) via MedWatch. In addition, although the FAERS passive reporting system is one mechanism to detect new safety signals, the increased use of real‐world data and real‐world evidence from electronic health records and other sources will undoubtedly improve our understanding of safety risks of anticancer therapies in the postmarketing setting. One advantage of real‐world evidence is that it may be able to better describe toxicity in patients with comorbidities such as cardiac, renal, or hepatic impairment who may have been excluded from the premarketing clinical trials 10, 11.

Withdrawals and/or REMS additions are rare (1 of 55) in oncology drug approvals and represent an outlier in new drug approvals. As new information emerged, FDA worked efficiently to communicate ponatinib's emerging risks to the public. Both the sponsor and FDA worked expeditiously to reassess the benefit‐risk profile of the drug and make corrective actions by narrowing the indication. The indication was narrowed to patients with advanced disease for whom limited therapeutic options are available and the benefit‐risk assessment in the refractory setting was more favorable than for patients in earlier lines of therapy with other options. Also, the existing Boxed Warning was expanded to further communicate the risk of ponatinib. In the case of ponatinib, it is apparent that postmarket surveillance was an important factor in ensuring the safety of this drug and that rapid identification and mitigation of safety signals are an integral part of the drug development process.

We recognize that our analysis has important limitations. Some safety‐related changes arising from modifications of existing Warnings and Precautions (Section 5) sections of the labeling were not included, as the analysis focused on new subsections or sections added to the prescribing information; less substantial safety‐related changes to Section 6 (Adverse Reactions) of the label were not analyzed; and we only evaluated the addition of substantial safety‐related changes within 2 years of initial drug approval. Furthermore, it is well known that many anticancer agents are approved at doses that are poorly tolerated for some patients, and the dose and/or schedules of these drugs are frequently adjusted in clinical practice. Although dose or schedule modification is beyond the scope of this analysis, it is acknowledged that expedited programs may limit the opportunity to optimize dosing in the premarketing setting 12.

Conclusion

Overall, the majority of drugs approved in OHOP did not have substantial safety‐related labeling changes within the first 2 years of approval. Although we found that more of these postapproval safety changes occurred with drugs approved using the AA pathway, with the exception of ponatinib, these additions did not change the benefit‐risk of the drugs and therefore would not have affected the approved indications had they been known at the time of initial approval. Because of expedited programs such as accelerated approval, patients have earlier access to promising new cancer drugs. Initial marketing approval is not the end of FDA's role in drug development, and knowledge will continue to be generated for both safety and efficacy in the postmarketing setting. Robust postmarketing safety surveillance strategies will continue to be critically important to monitor and communicate emerging risks and benefits to patients and their health care providers.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Janice Kim, Abhilasha Nair, Patricia Keegan, Julia A. Beaver, Paul G. Kluetz, Richard Pazdur, Meredith Chuk, Gideon M. Blumenthal

Provision of study material or patients: Janice Kim, Abhilasha Nair, Patricia Keegan, Julia A. Beaver, Paul G. Kluetz, Richard Pazdur, Meredith Chuk, Gideon M. Blumenthal

Collection and/or assembly of data: Janice Kim, Abhilasha Nair, Patricia Keegan, Julia A. Beaver, Paul G. Kluetz, Richard Pazdur, Meredith Chuk, Gideon M. Blumenthal

Data analysis and interpretation: Janice Kim, Abhilasha Nair, Patricia Keegan, Julia A. Beaver, Paul G. Kluetz, Richard Pazdur, Meredith Chuk, Gideon M. Blumenthal

Manuscript writing: Janice Kim, Abhilasha Nair, Patricia Keegan, Julia A. Beaver, Paul G. Kluetz, Richard Pazdur, Meredith Chuk, Gideon M. Blumenthal

Final approval of manuscript: Janice Kim, Abhilasha Nair, Patricia Keegan, Julia A. Beaver, Paul G. Kluetz, Richard Pazdur, Meredith Chuk, Gideon M. Blumenthal

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Appendices

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Erin P. Balogh, Andrew B. Bindman, S. Gail Eckhardt et al. Challenges and Opportunities to Updating Prescribing Information for Longstanding Oncology Drugs. The Oncologist 2020;25:e405–e411.

Abstract: A number of important drugs used to treat cancer–many of which serve as the backbone of modern chemotherapy regimens–have outdated prescribing information in their drug labeling. The Food and Drug Administration is undertaking a pilot project to develop a process and criteria for updating prescribing information for longstanding oncology drugs, based on the breadth of knowledge the cancer community has accumulated with the use of these drugs over time. This article highlights a number of considerations for labeling updates, including selecting priorities for updating; data sources and evidentiary criteria; as well as the risks, challenges, and opportunities for iterative review to ensure prescribing information for oncology drugs remains relevant to current clinical practice.

References

- 1. Code of Federal Regulations . Title 21 §314.126. Available at https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=8eea61dec0ef9b17f1fa0d0d3a7736c6&mc=true&node=se21.5.314_1126&rgn=div8. Published March 4, 2002. Accessed September 13, 2017.

- 2. Beaver JA, Howie LJ, Pelosof L et al. A 25‐year experience of US Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval of malignant hematology and oncology drugs and biologics: A review. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Downing NS, Shah ND, Aminawung JA et al. Postmarket safety events among novel therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration between 2001 and 2010. JAMA 2017;317:1854–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drugs @FDA: FDA‐Approved Drugs. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm. Accessed May 1, 2018.

- 5. Drug Safety Communications . U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/drug-safety-communications. Accessed May 1, 2018.

- 6. Drug Safety‐Related Labeling Changes (SrLC) . U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/safetylabelingchanges/. Accessed May 1, 2018.

- 7.Hematology/Oncology (Cancer) Approvals & Safety Notifications. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/hematologyoncology-cancer-approvals-safety-notifications. Accessed May 1, 2018.

- 8. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research , U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Warnings and Precautions, Contraindications, and Boxed Warning Sections of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products – Content and Format. Rockville, MD: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; October 2011. Available at https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/warnings-and-precautions-contraindications-and-boxed-warning-sections-labeling-human-prescription. Accessed May 1, 2018.

- 9. Mostaghim SR, Gagne JJ, Kesselheim AS. Safety related label changes for new drugs after approval in the US through expedited regulatory pathways: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2017;358:j3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khozin S, Blumenthal G, Pazdur R. Real‐world data for clinical evidence generation in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109:djx187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ et al. Real‐world evidence – What is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med 2016;375:2293–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schilsky RL, Rosen O, Minasian L et al. Optimizing dosing of oncology drugs. Issue Brief from the Conference on Clinical Cancer Research; November 2013. Available at https://www.focr.org/sites/default/files/Dosing%20Final%2011%204.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Appendices