Abstract

Density (ρ), viscosity (η) and surface tension (γ) of three amino acids (valine, alanine, and glycine) have been measured at a different mass fraction (0.002 - 0.009) of aqueous hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) mixtures and different temperatures (278.15 - 295.15 K). The formation of inclusion complexes has been analyzed via evaluating the amounts of apparent and limiting apparent molar volumes, limiting apparent molar expansibilities, activation energy, kinematic, relative, intrinsic, spatial, and dynamic viscosities. The surface tension studies indicated that the inclusion complexes have been formed with 1:1 stoichiometry and mediated by hydrophobic effects and electrostatic forces. Additionally, the ρ and η parameters were evaluated by molecular modeling experiments to provide more details on the mechanisms of the complexation.

Keywords: Theoretical chemistry, Pharmaceutical chemistry, Food science, Density, Dynamic viscosity, Activation energy, Kinematic viscosity, Amino acid, HP-β-cyclodextrin

Theoretical chemistry; Pharmaceutical chemistry; Food science; Density, Dynamic viscosity, Activation energy, Kinematic viscosity, Amino acid, HP-β-cyclodextrin

1. Introduction

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are a family of cyclic oligosaccharides consisting of six (α-CD), seven (β-CD) and eight (γ-CD) glucose subunits constructed from starch by enzymatic conversion (Chen et al., 2017). They are vastly used for the controlled release of compounds due to their exceptional ability to form inclusion complexes with a variety of guest molecules, represented an major duty to follow whether a molecule forms an inclusion complex with cyclodextrins (Chen et al., 2017; Szejtli, 1998).They have applications majorly in food, pharmaceutical, drug delivery, and chemical industries, and also environmental engineering (Wimmer, 2012; Adeoye and Cabral-Marques, 2017; Gao et al., 2006). In the pharmaceutical industry, β-CDs have mostly been used as complexing agents to increase aqueous solubility of imperfectly soluble drugs and to increase their bioavailability and stability. Thus, improved and comparatively safe β-CDs have been synthesized and used properly (Costa et al., 2015). 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (2-HP β CD) is a derivative of β-CD that hydroxypropyl groups replace the hydroxyl groups of C2, C3 and C6 of β-CD (Chen et al., 2017). HPβCD is known to be a mixture of various isomers (disparate orientation of hydroxypropyl groups) and comparable with different degree of substitution (Stella et al., 1997; Tablet et al., 2012). Amino acids have important interactions with cyclodextrins and have been intensively studied due to their properties that are similar to enzyme-substrate complexes (Huang et al., 2016). So, the physicochemical features of amino acids in aqueous solutions are mediated by solute-solute interactions and solute-solvent interactions that are important in several biochemical and physiological processes taken place in living systems (Zhao et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2016). Based on this insight, the present study focuses on the evaluations of density and viscosity of non-polar amino acids (valine, alanine, and glycine) from 0.002 to 0.009 mol kg−1 in aqueous solutions of HPβCD at different temperatures (278.15, 283.15, 288.15, 293.15, and 295.15K). Furthermore, the nature of the complexes will be defined using thermodynamic parameters, based on density, viscosity measurements by devious the portion to the various physicochemical parameters such as ΦV, , SV, , E, υ, , , , η which are computed within the experimental data. Finally, the results will be explicated in terms of solute solvent and solute-solute interactions in these complexes (Chen et al., 2017).

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Density study: group contributions and interactions between amino acids and cyclodextrins

Intitally, the density of solutions increases with increasing mass fraction of HPβCD at constant temperature due to structure built from a contribution of CDs with water molecules. The density of HPβCD decreases with increasing temperatures at constant mass fraction of HPβCD (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

Density of the solution against molality of the Amino acids at different temperatures and wHPβCD = 0.002.

Figure 2.

Density of the solution against molality of the Amino acids at different temperatures and wHPβCD = 0.009.

Figure 3.

Density of the solution against molality of the Amino acids at different mass fraction of HPβCD and T = 278 K.

Figure 4.

Density of the solution against molality of the Amino acids at different mass fraction of HPβCD and T = 295 K.

Then, to achieve our purpose, the values of are determined from the experimental values of density of the solutions using the proper equation (Masson, 1929) by taking 0.002, 0.004, 0.006, 0.008, 0.009 mass fractions of HPβCD at different temperatures (278.15 K–295.15 K). The results demonstrate that the magnitude of ΦV is larger and more positive for Valine rather than for alanine and glycine. This would describe that the values of ΦV increase linearly with the increase in the size of the alkyl chain of the amino acids and also with the increase in the mass fraction of HPβCD (0.002, 0.004, 0.006, 0.008, 0.009) in aqueous medium (Figures 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10). In this regards, the apparent molar volume of valine at 295.15 K and the mass fraction of 0.009 are greater than that of alanine and glycine, respectively, under the same conditions (ΦV (Valine, WHPβCD = 0.009, T = 295.15 K) > ΦV (Alanine, WHPβCD = 0.009, T = 295.15 K) > ΦV (Glycine, WHPβCD = 0.009, T = 295.15 K).

Figure 5.

Apparent molar volume against √m for Valine, Alanine, Glycine.

Figure 6.

Apparent molar volume against √m for Valine, Alanine, Glycine.

Figure 7.

Apparent molar volume against √m for Valine, Alanine, Glycine.

Figure 8.

Apparent molar volume against √m for Valine, Alanine, Glycine.

Figure 9.

Apparent molar volume against √m for Valine, Alanine, Glycine.

Figure 10.

Apparent molar volume against √m for Valine, Alanine, Glycine.

These findings also indicate stronger solute-solvent interactions of valine than alanine and alanine relatively to glycine at 295.15 K and 0.009 mass fraction of HPβCD (solute-solvent interactions increase with increasing concentration of HPβCD, size of the alkyl side chain of amino acids and temperature (Roy et al., 2016a, b). At all temperatures (278.15 K–295.15 K), the values of increase the size of the alkyl group from glycine to valine. Considering particular amino acids (such as Glycine, Valine, alanine), it is ascertained that the values of increase with increasing the mass fraction of HPβCD and temperature (Figures 11, 12 and 13). That means that the ion-hydrophilic group interactions, between zwitterionic centers of the amino acids and the –OH groups of HPβCD, are stronger than the ion-hydrophobic group interactions, between zwitterionic centers and non-polar parts of HPβCD, and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions, between non-polar parts of the amino acids and HPβCD (Roy et al., 2016a, b). Due to these interactions, the electrostriction of water caused by the charged centers of the amino acids will be reduced resulting in an increase in the volume and the order glycine < alanine < valine at each investigated temperature.

Figure 11.

Plot of limiting apparent molar volume against mass fraction of HPβCD for Glycine at different temperature.

Figure 12.

Plot of limiting apparent molar volume against mass fraction of HPβCD for Alanine at different temperature.

Figure 13.

Plot of limiting apparentlar volume against mass fraction of HPβCD for Valine at different temperature.

The increase of with increasing temperature may be identified to the release of some solvated molecules from the loose solvated layers of the solutes in solution. The apparent molar volume (ΦV) and limiting apparent molar volume () are considered to be sensitive tools for understanding the interactions taking place in solutions (Roy et al., 2014; Das et al., 2018). Where = is the apparent molar volume at infinite dilution (m < 0.1 mol kg−1). At infinite dilution, each monomer of solute is surrounded only by the solvent molecules, and being infinite distant with other ones. So, this would tell us that is unaffected by solute-solute interaction and it is a measure only of the solute-solvent interaction (Ekka and Roy, 2013). is found to be investigated for all the studied systems, suggesting that the pairwise interaction is restricted by the interaction of the charged functional group one molecule to chain of the other amino acids (Chen et al., 2017). A quantitative comparison between and values show that the magnitude of values is higher than , suggesting the solute-solvent interactions at the different temperatures (278.15–295.15 K). Furthermore, values are negative and have an irregular trend at all temperatures which are indicative of the fact that solute-solute interactions are influenced by number of effects (Figure 14) (Chen et al., 2017). The values of faintly increase with the increase of temperatures, and consequently the entropy of the solution increases with increasing temperature.

Figure 14.

Plot of SVagainst mass fraction of HPβCD at different temperatures.

Generally, 3D diagrams confirm the results obtained from the density section (Figures 15 and 16).

Figure 15.

3D diagram for inclusion of HPβCD-AA.

Figure 16.

3D diagram for inclusion of HPβCD-AA.

The values of limited apparent molar expansibility () for complexation of the studied three amino acids at different temperatures. are also employed to interpret the structure-making or breaking properties of various solutes (Kumar and Kaur et al., 2012). Positive expansibilities increase the volume with the increase at considered temperature for all the amino acids in aqueous HPβCD solutions (Wang et al., 2014). If limiting apparent molar expansibility is positive, the molecular is a structure maker. This trend in values indicates the presence of strong solute-solvent interactions and such interactions further strengthen at elevate temperature. values for valine is higher than alanine and glycine, respectively.

2.2. Viscosity: group contribution and solvation number: the degree of solvation by cyclodextrin molecules

Next, the viscosity of the aqueous solution of CD increases with the increase of mass fraction for HPβCD at constant temperature due to the structure making from contribution of HPβCD with water molecules. In the studied ternary systems the viscosity and activation energy (Arrhenius model: μ (T) = μ0 exp ()) of HPβCD-AA were found to be increased with the increase of molar concentration for valine, alanine and glycine (Figures 17 and 18). These consequences reveal that the values of dynamic viscosity increases with the increase in the mass fraction of HPβCD at constant temperature and also decrease with the increase of temperatures at constant mass fraction from HPβCD.

Figure 17.

Dynamic Viscosity against molality of Glycine at w = 0.002 and different temperatures.

Figure 18.

Dynamic Viscosity against molality of Glycine at w = 0.009 and different temperatures.

Furthermore, we focus on kinematic viscosity that refers to the ratio of dynamic viscosity (η) to density (ρ) at different temperatures and different molalities of amino acids. The results show that the kinematic viscosity of aqueous cyclodextrin decreases with increasing temperature at constant mass fraction of HPβCD and also increases with increasing mass fraction of HPBCD (Figures 19, 20, 21, and 22).

Figure 19.

Kinematic Viscosity against mass fraction of HPβCD and T = 278 K.

Figure 20.

Kinematic Viscosity against mass fraction of HPβCD and T = 278 K.

Figure 21.

Kinematic Viscosity against molality of amino acids in different temperatures and wHPβCD = 0.002.

Figure 22.

Kinematic Viscosity against molality of amino acids in different temperatures and wHPβCD = 0.009.

Activation energy (Ea), can be thought of the magnitude of the potential barrier (sometimes called the energy barrier) separating minima of the potential energy surface pertaining to the initial and final thermodynamic state (k = A). The results confirmed that activation energy increases with increasing molality of amino acids at constant mass fraction of HPβCD. The magnitude of Ea is higher for valine rather than alanine and glycine, respectively (Figures 23 and 24). It can be concluded from the above discussion that the rate constants decrease with incraesing molality and thus the rate of complex formation decreases. This decrease is larger for glycine than alanine and valine respectively (Ea (valine) > Ea (alanine) > Ea (alanine); k (glycine) > k (alanine) >k (valine)).

Figure 23.

Activation Energy against molality of amino acids in different temperatures and wHPβCD = 0.002.

Figure 24.

Activation Energy against molality of amino acids in different temperatures and wHPβCD = 0.009.

Additionally, we turned our attention to reduced viscosity that refers to the ratio of specific viscosity to the concentration of amino acids. Here, the reduced viscosity diagram versus concentration gives us intercept (intrinsic viscosity) and the gradient (slope) of the chart on the intrinsic viscosity (). The internal viscosity and the reduced viscosity are measured for each concentration that has a different viscosity. The intercept of the reduced viscosity graph is intrinsic in the viscosity concentration and the slope of the graph is dependent on the intrinsic viscosity. Usually, the intrinsic viscosity is calculated from both methods and if they fit each other, we realize that we have done all the steps correctly by shown the diagrams obtained from the two methods together in a coordinate system. The reduced viscosity of aqueous HPβCD decreases with increasing molal concentration of the above three amino acids and decreases with increasing temperature and increases with increasing mass fraction of HPBCD. The magnitude of reduced viscosity for valine is more than alanine whereas alanine is larger than glycine. The relative viscosity refers to the ratio of discharge time dissolved to solvent drain time. Spatial viscosity refers to the ratio of the difference in discharge time dissolved and solvent drain time to solvent drain time (). Spatial viscosity was obtained at different temperature and different mass fraction of HPβCD. Therefore, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29 confirm our findings for this research.

Figure 25.

3D diagram for inclusion of HPβCD-AA.

Figure 26.

3D diagram for inclusion of HPβCD-AA.

Figure 27.

3D diagram for inclusion of HPβCD-AA.

Figure 28.

3D diagram for inclusion of HPβCD-AA.

Figure 29.

3D diagram for inclusion of HPβCD-AA.

2.3. Surface tension study explains the inclusion as well as the stoichiometric ratio of the inclusion complexes

The surface tension (γ) measurement provides a considerable implication about the formation of inclusion complexes (IC) and also the stoichiometry of the host-guest assemblage. Each plot also indicates that there is a breakpoint at certain concentrations after which the slopes become less (Roy et al., 2016a, b). Finding of breakpoint in surface tension curve not only indicates the formation of IC but also provides information about its stoichiometry, i.e., the appearance of single, double and so on break point in the plot indicates 1:1, 1:2 and so on the stoichiometry of host: guest ICs (Roy et al., 2016a, b). In the present study the guest amino acids molecules exist in zwitterionic forms and contain basic side groups hence having a charge in their molecules. Therefore, it might be some ionic interactions between the charged groups resulting in an increase in surface tension of the aqueous medium, which would be definitely affected in the presence of HPβCD. Here a set of solutions has been prepared to have 4 mmol.L−1 concentration of alanine, valine, and glycine with increasing concentration of HPβCD and the surface tension is measured at 295 K surface tension curve is found to be steadily come down with increased concentration of HPβCD, which perhaps ascribed to the formation of the inclusion complex (Figure 30). The curves for all the amino acids are similar, but the slope of valine is higher than that of alanine and alanine higher glycine, which may be due to a greater number of valine molecules present in the charged structure than that of alanine and glycine, HPBCD of which is encapsulated in the cyclodextrin cavity as the inclusion occurs. Single discernible breaks at about 4 mmol.L−1 concentration of HPBCD are found for all the possible for three cases indicating the 1:1 stoichiometric ratio for each of the inclusion complexes formed (Table 1) (see Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 30.

Variation of surface tension of valine solution (4 mmol L−1) and alanine solution (4 mmol L−1) and glycine solution (4 mmol L−1) with increasing concentration of HPβCD at 295 K.

Table 1.

Values of surface tension (γ) at the break point with corresponding concentration of aqueous HPβCD at 295 K.

| Surface tension |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine | Alanine | Valine | ||||

| HPβCD | Conc./mM | γ/mN m−1 | Conc./mM | γ/mN m−1 | Conc./mM | γ/mN m−1 |

| 4 | 69.2 | 4 | 70 | 4 | 70.2 | |

Table 2.

Average density (ρ) of amino acids and their HPβCD complexes in water solution at different temperature parameters calculated for 250 ps using molecular dynamics with the GAFF force field.

| Ρ (g/) | Temperature (K) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 278.15 | 283.15 | 288.15 | 293.15 | 295.15 | |

| Alanine | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Glycine | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Val | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Ala-HPβCD | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Gly-HPβCD | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Val-HPβCD | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

Table 3.

Average viscosity (η) of amino acids and their HPβCD complexes in water solution at different temperature parameters calculated for 250 ps using molecular dynamics with the GAFF force field.

| η (μPa∗s) | Temperature (K) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 278.15 | 283.15 | 288.15 | 293.15 | 295.15 | |

| Alanine | 198.49 | 156.9 | 170.41 | 165.9 | 135.43 |

| Glycine | 175.01 | 214.09 | 208.87 | 169.48 | 207.49 |

| Val | 199.21 | 210.97 | 143.19 | 128.01 | 192.58 |

| Ala-HPβCD | 199.21 | 225.59 | 194.28 | 176.92 | 168.25 |

| Gly-HPβCD | 210.77 | 187.16 | 181.37 | 198.05 | 213.64 |

| Val-HPβCD | 220.94 | 222.82 | 216.8 | 209.46 | 223.87 |

2.4. Solid-state characterization of the inclusion compounds

The freeze-dried solids were studied by a range of techniques to confirm amino acids inclusion and to evaluate the purity and stability of the compounds and to study the geometry of inclusion of amino acids into HPBβCD and the supramolecular packing of the complex units in the solid state.

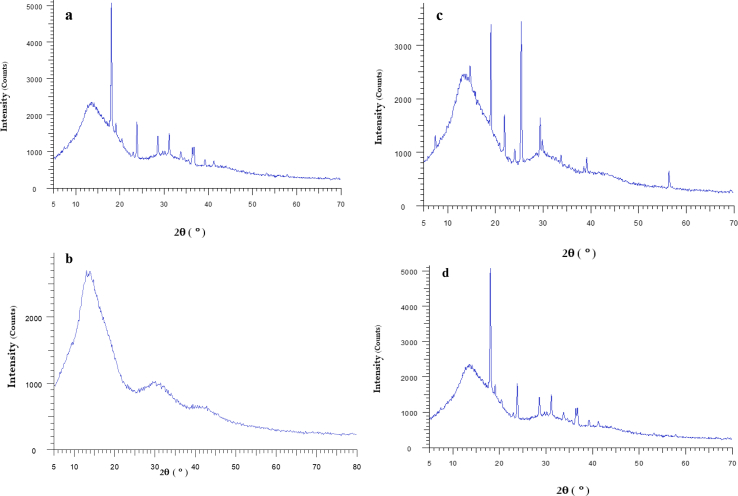

2.5. X-ray powder diffraction studies

XRD is an impressive procedure for exploring the complexation process of HPβCD and molecules in the powder or microcrystalline states. The powder X-Ray diffraction patterns of the aforementioned amino acids, 2-HP-β-CD, the physical mixture and the complex were shown in Figures 31, 32 and 33. The XRD patterns of amino acids display such sharp and intense vertex of the amino acids which are suggestive of its crystalline character are shifted, disappeared or become less intense in complexed forms due to encapsulations of amino acids into the hydrophobic cavity of 2-HP-β-CD. However, 2-HP-β-CD showed the amorphous lacking crystalline peaks.

Figure 31.

XRD patterns (a) Glycine, (b) 2-HP-β-CD, (c) Glycine/2-HP-β-CD physical mixture, (d) Glycine/2-HP-β-CD inclusion complex.

Figure 32.

XRD patterns (a) Alanine, (b) 2-HP-β-CD, (c) Alanine/2-HP-β-CD physical mixture, (d) Alanine/2-HP-β-CD inclusion complex.

Figure 33.

XRD patterns (a) Valine, (b) 2-HP-β-CD, (c) Valine/2-HP-β-CD physical mixture, (d) Valine/2-HP-β-CD inclusion complex.

2.6. FTIR (Fourier transform infrared spectra) studies

Characterization of the inclusion complex was performed in order to obtain further information on AA-2-HPβCD. The results showed a better host-guest formation in aqueous solution. To evaluate any possible interaction of the amino acids with 2- HPβCD in the solid state, the FTIR technique was employed (Liang et al., 2018). The FTIR spectra of amino acids (glycine, alanine and valine), 2-HP-β-CD, amino acids/2-HP-β-CD physical mixture and amino acids-2-HP-β-CD inclusion complex were shown in Figures 34, 35 and 36. Comparison of the FTIR spectra of amino acids with amino acids-2-HP-β-CD, our findings reveal that the stretch vibration of carbonyl groups (C=O) of glycine, alanine and valine were shifted from 1647 to 1664 , 1626 and 1613 respectively after encapsulating by the 2-HP-β-CD. The FTIR characteristic peaks of amino acids/2-HP-β-CD physical mixture induce changes compared with amino acids and 2-HP-β-CD, it could be inferred that amino acids and 2-HP-β-CD were mixed with host-guest interaction. FTIR spectra results clearly support the formation of the complexation between amino acids and 2-HP-β-CD.

Figure 34.

IR patterns (a) Glycine, (b) 2-HP-β-CD, (c) Glycine-HP-β-CD physical mixture, (d) Glycine-2-HP-β-CD inclusion complex.

Figure 35.

IR patterns (a) Alanine, (b) 2-HP-β-CD, (c) Alanine-HP-β-CD physical mixture, (d) Alanine-2-HP-β-CD inclusion complex.

Figure 36.

IR patterns (a) Valine, (b) 2-HP-β-CD, (c) Valine-HP-β-CD physical mixture, (d) Valine-2-HP-β-CD inclusion complex.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Experimental methods

The solubility of the HPβCD and that of the selected amino acids in medium solution with HPβCD has been exactly studied in Milli-Q water and it can be noted these were soluble in all amounts of aqueous Solution of HPβCD. All the solutions of the amino acids were prepared by mass (measured using Sartorius AG Gottingen with uncertainly 0.0001 g), and the working solutions were obtained by mass fraction at 295 K. The densities (ρ) of the solvents were measured by means an Anton Paar mPDS5 densitometer (DMA-HPM) with a precision of ±0.5 kg m−3 maintained at ±0.01 K of the desired temperature. It was calibrated by passing Milli-Q water and Glycerol and dry air. The viscosities (η) were measured using an Ostwald viscometer.

3.2. Computational methods

The amino acid and HPβCD structures were obtained from the PubChem database or from our previously published experimental data (Shityakov et al., 2016a, b). The AMBER 16 suite (Case et al., 2005), including AMBER Tools utilities, was used to perform all the molecular dynamics (MD) calculations. Prior to MD simulations, Gasteiger partial charges were assigned to the analyzed structures and complexes, which were further solvated using the TIP3P water model (Gasteiger, Marsili, 1978; Mark and Nilsson, 2001). The GAFF and FF99SB force fields without modifications were utilized to generate the corresponding topologies (Wang et al., 2004; Wickstrom et al., 2009). The minimization, heating (NVT ensemble), and production protocols were implemented to calculate the self-diffusion coefficients and density parameters using the previously published MD protocol (Eckler and Nee, 2016). Production runs of 250 ps in the NPT ensemble with a step size of 1 fs provided ample data to determine the viscosity values from the mean-squared displacement by means of by the Einstein-Smoluchowski and Stokes-Einstein equations (Eckler; Nee, 2016).

4. Conclusion

Thermodynamic properties of amino acids in different mass fraction of HPβCD at different temperatures (278–295 K) have been determined. From the experimental results, various parameters; , , SV, , Ea, υ, , , and η were calculated. The results indicate that the solute-solvent interaction is dominant over the solute-solute interaction in the systems. The structural effect of HP-β-CD gives the favorable support in the molecular interaction with retention of configuration and the difference side groups of amino acids affect the solute-solvent interaction. The variation of with temperature indicated that amino acids (alanine, glycine, valine) as structure-maker in different mass fraction of HPβCD. Surface tension studies reveal that 1:1 inclusion complexes have been formed. Evidently, the experimental results in this study complement each other and there are a consistency with the molecular modeling. The resulted detections demonstrate the formation of the inclusion complexes. Finally, the present work illustrates its proportion to various applications as a controlled delivery system in the field of modern bio-medical sciences.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Sergey Shityakov: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

D. Esmaeilpour: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

A. K. Bordbar, F. A. Almalki, A. A. Hussein: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the University of Isfahan.

Contributor Information

S. Shityakov, Email: shityakoff@hotmail.com.

A.K. Bordbar, Email: bordbar@chem.ui.ac.ir.

References

- Adeoye O., Cabral-Marques H. Cyclodextrin nanosystems in oral drug delivery: a mini review. Int. J. Pharm. 2017;531(2):521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrhenius S. On the reaction velocity of the inversion of cane sugar by acids. Zeitschrift Für Physikalische Chemie. 1889;4:226ff. [Google Scholar]

- Case D.A., Cheatham T.E., 3rd, Darden T., Gohlke H., Luo R., Merz K.M., Jr., Onufriev A., Simmerling C., Wang B., Woods R.J. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26(16):1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Yu., Ranran Fu., Jingjing Xu., Wenting Du., Wang Xu., Wenjun Fang. Thermodynamic (volume and viscosity) of amino acids in aqueous hydroxyl-propyl-β-cyclodextrin solutions at different temperatures. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2017;9614(17) 30235-5. [Google Scholar]

- Costa M.A.S., Anconi C.P.A., Santos H.F.D., Almedia W.B.D., Nascimento C.S. Inclusion prosses of tetracycline in βand γ-cyclodextrins; A theoretical investigation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2015;626:80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Das K., Datta B., Rajbakhshi B., Nath Roy.M. Evidences for inclusion and encapsulation of an ionic liquid with β-CD and 18-C-6 in aqueous environments by physicochemical investigation. J Physicalchemistry B. 2018 doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b11274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckler L.H., Nee M.J. A simple molecular dynamics lab to calculate viscosity as a function of temperature. J. Chem. Educ. 2016;93(5):927–931. [Google Scholar]

- Ekka D., Roy M.N. Molecular interactions of α-aminoacids insight into aqueous β-cyclodextrin systems. Amino Acids. 2013;45:755–777. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Zhao X., Dong B., Zheng L., Li N., Zhang S. Inclusion complexes of beat-cyclodextrin with ionic liquid surfactants. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:8576–8581. doi: 10.1021/jp057478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger J., Marsili M. New model for calculating atomic charges in molecules. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;(34):3181–3184. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Jang L., Liang W., Gui J., Xu D., Wu W., Nakai Y., Nishijima M., Fukuhara G., Mori T., Inoue Y. Inherently chiral azaonia [6] helicene-modified β-cyclodextrin: synthesis, characterization, and chirality sensing of underivatized amino acids in water. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:3430–3434. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H., Kaur K. Investigation on molecular interaction of amino acids in antibacterial drug ampicillin solutions with reference to volumetric and compressibility measurements. J. Mol. Liq. 2012;173:130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Guizhao, Li Jiaqi, Geng Sheng, Liu Benguo, Wang Huabin. Self-assembled mechanism of hydrophobic amino acids and β-cyclodextrin based on experimental and computational methods. J., Food research Int. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark P., Nilsson L. Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105(43) 24a-24a. [Google Scholar]

- Masson Sir. D. Orme., K.B.E.F.R.S. XXVIII. Solute molecular volumes in relation to solvation and ionization. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 1929;8(49):218–235. [Google Scholar]

- Roy M.N., Ekka D., Saha S. Host-guest inclusion complexes of αand β-cyclodextrins with α-amino acids. RSC Adv. 2014;4:42383–42390. [Google Scholar]

- Roy M.N., Saha S., Barman S., Ekka D. Host-guest inclusion complexes of RNA nucleosides inside aqueous cyclodextrins explored by physicochemical and spectroscopic methods. RSC Adv. 2016;6:8881–8891. [Google Scholar]

- Roy M.N., Saha S., Roy A. Study to explore the mechanism to form inclusion complexes of β-cyclodextrin with vitamin molecules. New J. Chem. 2016;40:651–661. doi: 10.1038/srep35764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shityakov S., Salmas R.E., Durdagi S., Salvador E., Papai K., Yanez-Gascon M.J., Perez-Sanchez H., Puskas I., Roewer N., Forster C., Broscheit J.-A. Characterization, in vivo evaluation, and molecular modeling of different propofol-cyclodextrin complexes to assess their drug delivery potential at the blood-brain barrier level. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016;56(10):1914–1922. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shityakov S., Salmas R.E., Salvador E., Roewer N., Broscheit J., Forster C. Evaluation of the potential toxicity of unmodified and modified cyclodextrins on murine blood-brain barrier endothelial cells. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2016;41(2):175–184. doi: 10.2131/jts.41.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella V.J., Rajewski R.A., Cyclodextrin Their future in drug formulation and delivery. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 1997;14:556–567. doi: 10.1023/a:1012136608249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szejtli J. Introduction and general overview of cyclodextrin chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;98(5):1743–1754. doi: 10.1021/cr970022c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tablet C., Minea L., Dumitrache L., Hillebrand M. Experimental and theoretical study of the inclusion complexes of 3-carboxycoumarin acid with β- and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrins. Spectrochim. Acta. 2012;92:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wolf R.M., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25(9):1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Xu, Li Guangqian, Guo Yuhua, Zheng Quing, Fang Wenjun, Bian Pingfeng, Lijun Zhang J. chem.Thermodynamics. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrom L., Okur A., Simmerling C. Evaluating the performance of the ff99SB force field based on NMR scalar coupling data. Biophys. J. 2009;97(3):853–856. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer T. Cyclodextrin-scaffolded alamethicin with remarkably efficient membrane permeabilizing properties and membrane current conductance. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116(26):7652–7659. doi: 10.1021/jp2098679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Ma P., Li J. Partial molar volumes and viscosity B-coefficients of arginine in aqueous glucose, sucrose and L-ascorbic acid solutions at T=298.15 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2005;37:37–42. [Google Scholar]