Abstract

Aims

Left ventricular (LV) remodelling after ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) worsens outcome. The effect of sex on LV post‐infarct remodelling is unknown. We therefore investigated the sex distribution and long‐term prognosis of LV post‐infarct remodelling after STEMI in the contemporary era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and optimal pharmacotherapy.

Methods and results

Data were obtained from an ongoing primary PCI STEMI registry. LV remodelling was defined as ≥20% increase in LV end‐diastolic volume at either 3, 6, or 12 months post‐infarct, and LV remodelling impact on outcome was evaluated with a log‐rank test. A total population of 1995 STEMI patients were analysed (mean age 60 ± 12 years): 1527 (77%) men and 468 (23%) women. The mean age of male patients was 60±11 versus 63±13 years for women (P < 0.001). A total of 953 (48%) patients experienced LV remodelling in the first 12 months of follow‐up, and it was equally frequent amongst men (n = 729, 48%) and women (n = 224, 48%). After a median follow‐up of 94 (interquartile range 69–119) months, 225 patients died: 171 (11%) men and 54 (12%) women. No survival difference was seen between remodellers and non‐remodellers in the male (P = 0.113) and female (P = 0.920) groups.

Conclusion

LV post‐infarct remodelling incidence, as well as long‐term survival of LV remodellers and non‐remodellers, was similar in men and women who were treated with primary PCI and optimal pharmacotherapy post‐STEMI.

Keywords: LV remodelling, Post‐infarct, Sex, Prognosis

1. Introduction

Women have a worse long‐term survival after ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) than men, even when treated with guideline‐directed primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and optimal pharmacotherapy [routine prescription of statins, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and thienopyridines].1 The reasons for this are unclear, but might relate to left ventricular (LV) remodelling. LV remodelling is a complication that occurs in almost half of STEMI patients during the first year after the event, and it is caused by an inflammatory response, myocardial extracellular matrix degradation, muscle bundle slippage, and apoptosis.2, 3, 4 Although LV post‐infarct remodelling has been linked to increased mortality in the past, this does not appear to be the case in the current era of primary PCI and guideline‐directed medical therapy.4 Conflicting data exist on sex differences in LV post‐infarct remodelling.2 The impact of sex on the incidence and long‐term prognosis of LV post‐infarct remodelling has not been investigated in a large cohort of patients receiving contemporary, guideline‐based treatment. We therefore investigated a registry of STEMI patients, treated with primary PCI and guideline‐based medical therapy, for (i) the impact of sex on the incidence of LV post‐infarct remodelling in the first 12 months after the event and (ii) differences in survival between patients with and without LV post‐infarct remodelling in male and female groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and data collection

Data (clinical, angiographic and echocardiographic) were collected from an ongoing registry of patients with STEMI, who received primary PCI at the Leiden University Medical Centre (the Netherlands), according to a standardized, institutional protocol (MISSION!).5 This management protocol is based on contemporary guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and includes culprit vessel PCI, aspirin, beta‐blockers, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, aldosterone receptor antagonists [for heart failure patients with an LV ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%], statins, and thienopyridines.6, 7 All patients were followed up during the first year after admission at the outpatient clinic of the Leiden University Medical Centre and underwent transthoracic echocardiography within 48 h of admission for STEMI, as well as at 3, 6, and 12 months. Subsequently, patients were referred to primary care centres or cardiology outpatient referral clinics. All data used for the present study were acquired for clinical purposes and handled anonymously. Written informed consent on a patient level was waived by the Institutional Review Board, due to the retrospective nature of the study. The investigation conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.8

2.2. Transthoracic echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed at rest and in the left lateral decubitus position with a commercially available echocardiography system (VIVID 7 or E9, General Electric Vingmed Ultrasound, Milwaukee, USA). Images (including M‐mode, two‐dimensional, and Doppler) were acquired with either 3.5 MHz or M5S transducers and archived digitally for offline analysis (EchoPac 202, General Electric Vingmed Ultrasound, Milwaukee, USA). Measurement of chamber dimensions [LV end‐systolic volume, LV end‐diastolic volume (LVEDV) and LVEF] was performed with the Simpson's biplane method, using two‐dimensional apical, two‐chamber and four‐chamber views.9 The linear method was employed for LV mass calculation.9 Wall motion score index was calculated by summation of individual segment scores (1 = normokinesia or hyperkinesia, 2 = hypokinesia, 3 = akinesia, 4 = dyskinesia), divided by the total score from all 16 segments.

2.3. Data analysis and left ventricular remodelling definition

An increase in the LVEDV of ≥20% (compared with baseline LVEDV at 0 months) at any time during the first 12 months after STEMI was used as a threshold for determining the presence of LV remodelling.10 This definition was applied to follow‐up at 3, 6, and 12 months, and patients with LV remodelling at any of those time points (early, mid‐term, or late, respectively) were classified as LV remodellers. Inclusion into any of the three groups (early, mid‐term, or late LV remodeller) excluded allocation to either of the remaining two groups. This approach was taken to account for the dynamic nature of LV post‐infarct remodelling. The study population was therefore dichotomized according to sex (male and female) and remodelling status (LV remodellers and LV non‐remodellers) during the first year after STEMI.

2.4. Study endpoints

Patients were followed up for the occurrence of all‐cause mortality after 12 months had elapsed since the index event [median follow‐up 94 (interquartile range 69–119) months]. Both municipal registries and telephonic follow‐up were used for collecting survival data.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Normally distributed, continuous data are presented as mean and standard deviation and non‐normally distributed data as median and interquartile range. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical comparisons were performed with Student's t‐tests or Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables and with χ2 and Fisher's exact tests (as appropriate) for categorical variables. The Kaplan–Meier method was applied to survival analysis, and groups were compared with a log‐rank test. The spss version 23.0 (SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) was utilized for all statistical analyses. All tests were two‐sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total population of 1995 STEMI patients was analysed (mean age 60 ± 12 years), including 1527 (77%) men and 468 (23%) women. The mean age for men was 60 ± 11 years, compared with 63 ± 13 years for women (P < 0.001). Baseline clinical and echocardiographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. While smoking was more common amongst men, women more frequently had a family history of ischaemic heart disease and hypertension. Multivessel disease (≥50% stenosis in >1 epicardial coronary artery) was more commonly observed in men. As expected, LV mass and chamber dimensions were smaller in women (Table 2). There was no difference in guideline‐directed discharge medications between men and women.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and echocardiographic patient characteristics

| Overall population (N = 1995) | Men (n = 1527) | Women (n = 468) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60 ± 12 | 60 ± 11 | 63 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 701 (35) | 509 (33) | 192 (41) | 0.009 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 401 (20) | 319 (21) | 82 (18) | 0.279 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 934 (47) | 722 (47) | 212 (45) | 0.016 |

| Ex‐smoker, n (%) | 225 (11) | 198 (13) | 27 (6) | <0.001 |

| Family history of IHD, n (%) | 844 (42) | 614 (40) | 230 (49) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 207 (10) | 149 (10) | 58 (12) | 0.102 |

| Previous infarct, n (%) | 158 (8) | 138 (9) | 20 (4) | 0.003 |

| Killip class, n (%) | ||||

| I | 1915 (96) | 1471 (96) | 444 (95) | 0.159 |

| II | 41 (2) | 28 (2) | 13 (3) | 0.208 |

| III | 12 (1) | 7 (1) | 5 (1) | 0.127 |

| IV | 27 (1) | 21 (1) | 6 (1) | 0.879 |

| Peak cTnT (μg/L) | 3.5 (1.4–7.3) | 3.8 (1.4–7.5) | 2.9 (1.1–6.3) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 98.7 ± 33.2 | 103.0 ± 32.7 | 84.7 ± 30.8 | <0.001 |

| Infarct location LAD or LMS, n (%) | 868 (44) | 653 (43) | 215 (46) | 0.225 |

| Multivessel CAD, n (%) | 1073 (54) | 852 (56) | 221 (47) | 0.001 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LV mass (g) | 200 (163–244) | 209 (174–254) | 170 (138–198) | <0.001 |

| Indexed LV mass (g/m2) | 101 (85‐121) | 105 (87‐125) | 93 (79‐109) | <0.001 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 106 ± 33 | 112 ± 33 | 87 ± 25 | <0.001 |

| LVESV (ml) | 57 ± 23 | 60 ± 23 | 46 ± 17 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 47 ± 9 | 47 ± 9 | 47 ± 9 | 0.309 |

| WMSI | 1.38 (1.19–1.63) | 1.38 (1.19–1.63) | 1.44 (1.19–1.69) | 0.432 |

| Medication | ||||

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 1887 (95) | 1442 (94) | 445 (95) | 0.761 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 1921 (96) | 1469 (96) | 452 (97) | 0.826 |

| Statin, n (%) | 1982 (99) | 1519 (99) | 463 (99) | 0.428 |

| ACE/ARB, n (%) | 1943 (97) | 1494 (98) | 449 (96) | 0.078 |

| Thienopyridinea | 1981 (99) | 1515 (99) | 466 (99) | 0.576 |

Continuous variables presented as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CAD, coronary artery disease; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LMS, left main stem; LV, left ventricular; LVEDV, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end‐systolic volume; WMSI, wall motion score index. These indicate significant values.

clopidogrel or prasugrel

Table 2.

Echocardiographic patient characteristics during follow‐up

| Overall population (N = 1995) | Men (n = 1527) | Women (n = 468) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography 3 months | ||||

| LV mass (g) | 200 (164–240) | 209 (176–247) | 169 (143–212) | <0.001 |

| Indexed LV mass (g/m2) | 102 (86–120) | 104 (88–121) | 95 (81–115) | <0.001 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 115 ± 39 | 122 ± 39 | 94 ± 32 | <0.001 |

| LVESV (ml) | 58 ± 28 | 61 ± 29 | 47 ± 22 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 51 ± 10 | 51 ± 10 | 52 ± 9 | 0.394 |

| WMSI | 1.25 (1.12–1.50) | 1.25 (1.12–1.50) | 1.19 (1.12–1.50) | 0.534 |

| Echocardiography 6 months | ||||

| LV mass (g) | 196 (162–240) | 206 (171–248) | 167 (138–202) | <0.001 |

| Indexed LV mass (g/m2) | 101 (84–119) | 102 (86–120) | 95 (79–113) | <0.001 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 114 ± 38 | 120 ± 38 | 93 ± 31 | <0.001 |

| LVESV (ml) | 57 ± 31 | 60 ± 33 | 45 ± 23 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 52 ± 10 | 52 ± 10 | 53 ± 10 | 0.121 |

| WMSI | 1.19 (1.06–1.50) | 1.19 (1.06–1.50) | 1.13 (1.00–1.50) | 0.173 |

| Echocardiography 12 months | ||||

| LV mass (g) | 194 (162–234) | 201 (170–242) | 167 (138–198) | <0.001 |

| Indexed LV mass (g/m2) | 100 (84–119) | 102 (86–121) | 92 (79–109) | <0.001 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 110 ± 38 | 116 ± 38 | 90 ± 32 | <0.001 |

| LVESV (ml) | 54 ± 29 | 57 ± 30 | 43 ± 23 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 53 ± 10 | 53 ± 10 | 54 ± 10 | 0.002 |

| WMSI | 1.13 (1.00–1.50) | 1.19 (1.00–1.50) | 1.13 (1.10–1.50) | 0.140 |

Continuous variables presented as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range.

LV, left ventricular; LVEDV, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end‐systolic volume; WMSI, wall motion score index.

3.1. Incidence of left ventricular remodelling

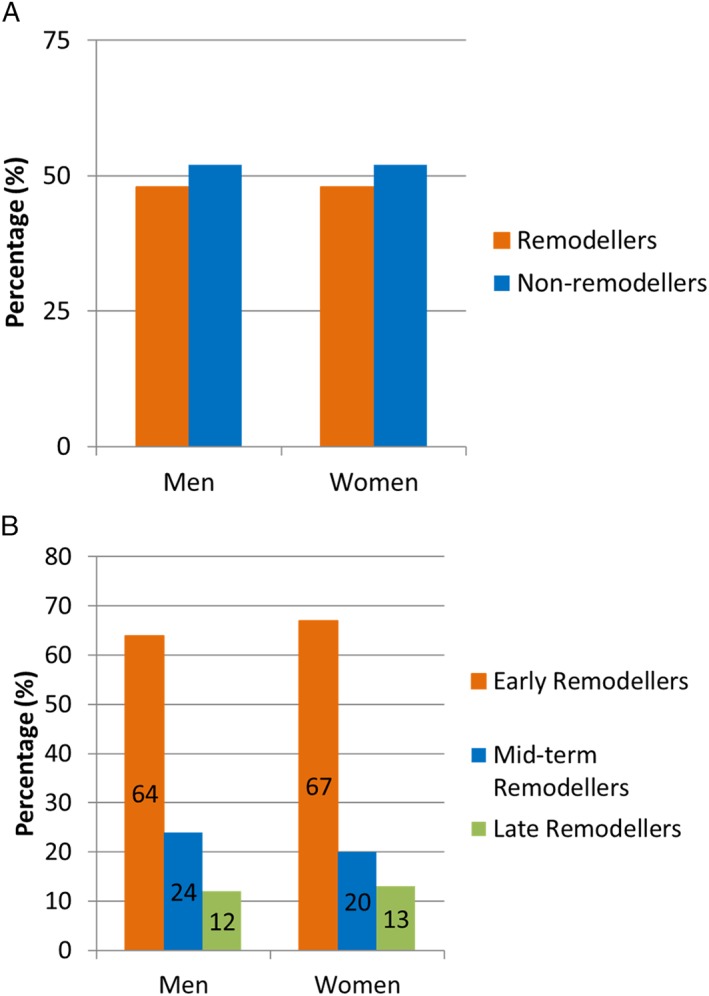

A total of 953 (48%) patients experienced LV remodelling in the first 12 months of follow‐up. Post‐infarct LV remodelling was observed with a similar frequency in men (n = 729, 48%) and women (n = 224, 48%) during the first year post‐STEMI (Figure 1 A). By 3 months, 463 (64%) men and 150 (67%) women had experienced post‐infarct remodelling and could be classified as early post‐infarct remodellers. The corresponding mid‐term remodelling numbers were 172 (24%) and 44 (20%) for men and women, respectively. By 12 months after the index event, 94 (12%) and 30 (13%) of men and women, respectively, had undergone late remodelling (Figure 1 B).

Figure 1.

Distribution of men and women with left ventricular, post‐infarct remodelling. (A) Percentage (%) of left ventricular remodellers and non‐remodellers (in the first year after ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction) and (B) percentage (%) of early, mid‐term, and late left ventricular remodellers, according to temporal pattern, in men and women.

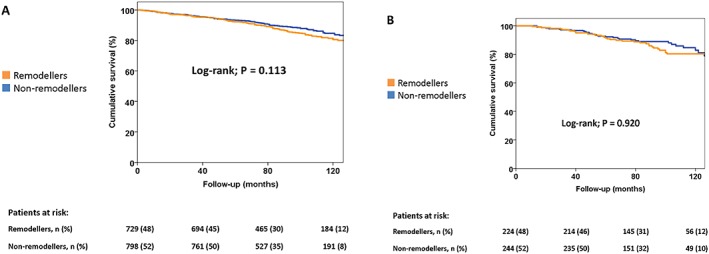

3.2. Left ventricular remodelling and all‐cause mortality

After a median follow‐up of 94 (interquartile range 69–119) months, 225 patients died: 171 were men (11%) and 54 were women (12%). Men who were classified as LV remodellers demonstrated a cumulative event rate of 5%, 11%, and 20% for all‐cause mortality at 40, 80, and 120 months, respectively. Men without post‐infarct LV remodelling experienced similar cumulative event rates: 5%, 9%, and 16% for the same time intervals (log‐rank test, P = 0.113; Figure 2 A). No significant difference in cumulative event rates was observed between women with and without post‐infarct LV remodelling in the first year after STEMI: 5%, 11%, and 20% and 3%, 10%, and 16% for all‐cause mortality at 40, 80, and 120 months, respectively (log‐rank test, P = 0.920; Figure 2 B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves, according to sex and remodelling status. Time to cumulative survival in men (A) and women (B), according to the presence of left ventricular remodelling in the first 12 months after ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

4. Discussion

In the present study, LV post‐infarct remodelling was observed with equal frequency in male and female STEMI patients (about 50% remodelling in each group) during the first 12 months after the event. In addition, no significant differences were observed in long‐term survival between LV remodellers and non‐remodellers in male and female groups.

4.1. Incidence of left ventricular post‐infarct remodelling in men and women

Conflicting data exist on sex differences in LV post‐infarct remodelling, with some reports suggesting that it is more common amongst men, while others describe a higher frequency in women.2, 10, 11, 12, 13 The incidence of LV remodelling depends to some degree on its definition, although this should not in principle affect the comparison between sexes. The definition of LV post‐infarct remodelling used in the present article takes account of its dynamic nature,10 and we found no difference in the incidence of LV remodelling in the first 12 months after STEMI between men and women. While a larger infarct size is associated with the occurrence of post‐infarct LV remodelling,14 no sex difference in infarct size was identified in a large meta‐analysis of STEMI patients (>2500 patients), where infarct size was measured with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) or 99mtechnetium single photon emission computed tomography.1 Similarly, infarct size did not differ significantly between men and women in a STEMI cohort where patients received primary PCI.15 Although we found higher troponin T levels in men than in women, this likely reflects the sex dependence of assays, so that the absolute values cannot be compared directly.16 This should therefore not be construed as an indicator of larger infarct size per se in men.16 Microvascular obstruction (quantified with CMR) has also been associated with LV post‐infarct remodelling.14 The extent of microvascular obstruction in men and women is variable, and while one study found that women have less microvascular obstruction compared to men,17 another large registry did not show any sex differences.15 Intramyocardial haemorrhage is another aetiological factor that is implicated in post‐infarct LV remodelling, and it appears to be more common in male STEMI patients.18, 19

The efficacy of reperfusion therapy is related at least in part to the degree of LV post‐infarct remodelling, which will develop with time.20 When reperfusion efficacy was quantified using the CMR‐derived ‘myocardial salvage index’, women had a higher reperfusion efficacy than men.2 Advanced age is also known to be a risk factor for LV post‐infarct remodelling.21 Consistent with other reports, female STEMI patients in our study population were older.1, 15 Although ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and aldosterone antagonists ameliorate post‐infarct LV remodelling,22, 23 there is little clinical evidence for a differential effect in men and women. Preclinical data suggest that sex‐based differences may exist, for example, a more beneficial effect of aldosterone antagonists on post‐infarct LV remodelling in female rats.24

The evidence demonstrating sex differences in different parameters known to impact on LV post‐infarct remodelling (e.g. infarct size, microvascular obstruction, intramyocardial haemorrhage, reperfusion efficacy, age, and pharmacotherapy) is not consistent across the various registries.2, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 However, the composite effect does not lead to any sex difference in the prevalence of LV remodelling in the first 12 months after STEMI in a population treated with primary PCI and guideline‐based medical therapy.

4.2. Left ventricular remodelling and long‐term survival: impact of sex

In prior studies, women were reported to have a worse outcome after STEMI when compared with men, even in the era of primary PCI and optimal pharmacotherapy.1 Although post‐infarct LV remodelling has been associated with secondary mitral regurgitation, ventricular arrhythmias, heart failure, and increased mortality in the past, modern treatment of STEMI with primary PCI and optimal medical therapy has improved the outcome considerably.25, 26, 27, 28 In a recent CMR study of 498 STEMI patients, post‐infarct LV remodelling was not independently associated with the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, or ventricular arrhythmias.4 LV remodelling was, however, still associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization, and ventricular arrhythmias in the presence of a decrease in LVEF >3%.4 This concurs with our data, where no difference in mortality rates is seen between LV post‐infarct remodellers and non‐remodellers in both sexes and can most likely be attributed to the revolution in STEMI management that has occurred with replacement of pharmacological thrombolysis with primary PCI and the introduction of optimal medical therapy.29 Our data therefore do not support the fact that higher mortality post‐STEMI in women can be ascribed to sex differences in post‐infarct LV remodelling, because (i) post‐infarct LV remodelling does not significantly impact on mortality in the modern era of primary PCI and optimal medical therapy and (ii) no differences exist in the incidence of LV post‐infarct remodelling between men and women.

The worse long‐term prognosis experienced by women after STEMI may be caused by higher baseline risk, as well as treatment differences.2, 15 While female STEMI patients in the present study were older and had a higher frequency of hypertension (consistent with data from previous studies investigating sex differences in STEMI1, 2), other baseline risk factors were similar or worse in men. In addition, we did not identify any differences in discharge medications between men and women in our cohort. Because there is no difference in either the incidence or the mortality implications of post‐infarct LV remodelling in men and women, both sexes should receive (i) post‐infarct surveillance with equal frequency and (ii) an identical degree of prevention for LV post‐infarct remodelling. Some investigators have reported women to be less likely to receive guideline‐directed therapy than men, and our study therefore adds to the published data that female patients with STEMI are not to be considered at lower risk than men and should receive equal, guideline‐based treatment.1

This study represents a single‐centre, retrospective experience, with on‐site echocardiographic analysis and locally adjudicated clinical events. Although the numbers of men and women were not comparable, this is a limitation of a retrospective study, where groups are not prespecified. The percentage of women (23%) in our cohort was very closely aligned to a recent, large meta‐analysis comparing clinical characteristics and outcomes of STEMI between sexes.1 We were unable to perform sub‐analyses for cardiac and all‐cause mortality, or to adjust for possible changes in prescription or adherence to medical therapy during the first 12 months post‐infarct. While separate survival analyses for both sexes at different time points (i.e. 3, 6, and 12 months) would have provided insight into the temporal patterns of LV post‐infarct remodelling and its outcome implications, individual groups were underpowered in our cohort for performing such an analysis in a clinically meaningful manner. This will require multicentre data. CMR data were not systematically available for our study population to quantify infarct size, microvascular obstruction, and myocardial salvage. We also could not assess the impact of a previous infarct on post‐infarct remodelling in a subsequent infarct by quantifying the baseline scar burden, for which CMR data would be required. The effect of the age of menopause could impact on post‐infarct LV remodelling, with preclinical data demonstrating a dose‐dependent effect of oestrogen replacement on this process.30 We were unable to adjust our analysis for this potential confounder.

The incidence of LV remodelling in the first year post‐infarct was similar between men and women, when investigated in a large cohort of STEMI patients treated with primary PCI and guideline‐directed medical therapy. Furthermore, there was no difference in long‐term survival between LV remodellers and non‐remodellers in male and female groups. Both men and women should therefore receive guideline‐based STEMI therapy, as well as equally careful surveillance and prevention for post‐infarct LV remodelling.

Conflict of interest

The Department of Cardiology, Heart Lung Centre, Leiden University Medical Centre has received research grants from Biotronik, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, GE Healthcare, and Edwards Lifesciences. V. D. received speaker fees from Abbott Vascular and Medtronic. N. A. M. received speaker fees from Abbott Vascular. J. J. B. received speaker fees from Abbott Vascular. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgements

P. V. D. B. and V. D. had full access to all data and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All individuals who contributed to this publication have been included as authors.

van der Bijl, P. , Abou, R. , Goedemans, L. , Gersh, B. J. , Holmes, D. R. Jr , Ajmone Marsan, N. , Delgado, V. , and Bax, J. J. (2020) Left ventricular remodelling after ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: sex differences and prognosis. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 474–481. 10.1002/ehf2.12618.

References

- 1. Kosmidou I, Redfors B, Selker HP, Thiele H, Patel MR, Udelson JE, Magnus Ohman E, Eitel I, Granger CB, Maehara A, Kirtane A, Genereux P, Jenkins PL, Ben‐Yehuda O, Mintz GS, Stone GW. Infarct size, left ventricular function, and prognosis in women compared to men after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from an individual patient‐level pooled analysis of 10 randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 1656–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canali E, Masci P, Bogaert J, Bucciarelli Ducci C, Francone M, McAlindon E, Carbone I, Lombardi M, Desmet W, Janssens S, Agati L. Impact of gender differences on myocardial salvage and post‐ischaemic left ventricular remodelling after primary coronary angioplasty: new insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 13: 948–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sutton MG, Sharpe N. Left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: pathophysiology and therapy. Circulation 2000; 101: 2981–2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodriguez‐Palomares JF, Gavara J, Ferreira‐Gonzalez I, Valente F, Rios C, Rodriguez‐Garcia J, Bonanad C, Garcia Del Blanco B, Minana G, Mutuberria M, Nunez J, Barrabes J, Evangelista A, Bodi V, Garcia‐Dorado D. Prognostic value of initial left ventricular remodeling in patients with reperfused STEMI. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging Published online ahead of print 8 June 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liem SS, van der Hoeven BL, Oemrawsingh PV, Bax JJ, van der Bom JG, Bosch J, Viergever EP, van Rees C, Padmos I, Sedney MI, van Exel HJ, Verwey HF, Atsma DE, van der Velde ET, Jukema JW, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ. MISSION!: optimization of acute and chronic care for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2007; 153: 14 e1–14 e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimsky P, Group ESCSD . 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Task Force on the management of STseamiotESoC , Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom‐Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez‐Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, van't Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rickham PP. Human experimentation. Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Br Med J 1964; 2: 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015; 16: 233–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bolognese L, Neskovic AN, Parodi G, Cerisano G, Buonamici P, Santoro GM, Antoniucci D. Left ventricular remodeling after primary coronary angioplasty: patterns of left ventricular dilation and long‐term prognostic implications. Circulation 2002; 106: 2351–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeremy RW, Allman KC, Bautovitch G, Harris PJ. Patterns of left ventricular dilation during the six months after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989; 13: 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ito H, Yu H, Tomooka T, Masuyama T, Aburaya M, Sakai N, Watada H, Hori M, Higashino Y, Fujii K, Minamino T. Incidence and time course of left ventricular dilation in the early convalescent stage of reperfused anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1994; 73: 539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li F, Chen YG, Yao GH, Li L, Ge ZM, Zhang M, Zhang Y. Usefulness of left ventricular conic index measured by real‐time three‐dimensional echocardiography to predict left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2008; 102: 1433–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lombardo A, Niccoli G, Natale L, Bernardini A, Cosentino N, Bonomo L, Crea F. Impact of microvascular obstruction and infarct size on left ventricular remodeling in reperfused myocardial infarction: a contrast‐enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 28: 835–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eitel I, Desch S, de Waha S, Fuernau G, Gutberlet M, Schuler G, Thiele H. Sex differences in myocardial salvage and clinical outcome in patients with acute reperfused ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: advances in cardiovascular imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 5: 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gore MO, Seliger SL, Defilippi CR, Nambi V, Christenson RH, Hashim IA, Hoogeveen RC, Ayers CR, Sun W, McGuire DK, Ballantyne CM, de Lemos JA. Age‐ and sex‐dependent upper reference limits for the high‐sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 1441–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Langhans B, Ibrahim T, Hausleiter J, Sonne C, Martinoff S, Schomig A, Hadamitzky M. Gender differences in contrast‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 29: 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carrick D, Haig C, Ahmed N, Rauhalammi S, Clerfond G, Carberry J, Mordi I, McEntegart M, Petrie MC, Eteiba H, Hood S, Watkins S, Lindsay MM, Mahrous A, Welsh P, Sattar N, Ford I, Oldroyd KG, Radjenovic A, Berry C. Temporal evolution of myocardial hemorrhage and edema in patients after acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: pathophysiological insights and clinical implications. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: pii: e002831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ganame J, Messalli G, Dymarkowski S, Rademakers FE, Desmet W, Van de Werf F, Bogaert J. Impact of myocardial haemorrhage on left ventricular function and remodelling in patients with reperfused acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 1440–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Masci PG, Ganame J, Strata E, Desmet W, Aquaro GD, Dymarkowski S, Valenti V, Janssens S, Lombardi M, Van de Werf F, L'Abbate A, Bogaert J. Myocardial salvage by CMR correlates with LV remodeling and early ST‐segment resolution in acute myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010; 3: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shih H, Lee B, Lee RJ, Boyle AJ. The aging heart and post‐infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Solomon SD, Skali H, Anavekar NS, Bourgoun M, Barvik S, Ghali JK, Warnica JW, Khrakovskaya M, Arnold JM, Schwartz Y, Velazquez EJ, Califf RM, McMurray JV, Pfeffer MA. Changes in ventricular size and function in patients treated with valsartan, captopril, or both after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2005; 111: 3411–3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hayashi M, Tsutamoto T, Wada A, Tsutsui T, Ishii C, Ohno K, Fujii M, Taniguchi A, Hamatani T, Nozato Y, Kataoka K, Morigami N, Ohnishi M, Kinoshita M, Horie M. Immediate administration of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone prevents post‐infarct left ventricular remodeling associated with suppression of a marker of myocardial collagen synthesis in patients with first anterior acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2003; 107: 2559–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanashiro‐Takeuchi RM, Heidecker B, Lamirault G, Dharamsi JW, Hare JM. Sex‐specific impact of aldosterone receptor antagonism on ventricular remodeling and gene expression after myocardial infarction. Clin Transl Sci 2009; 2: 134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. St John Sutton M, Pfeffer MA, Plappert T, Rouleau JL, Moye LA, Dagenais GR, Lamas GA, Klein M, Sussex B, Goldman S. Quantitative two‐dimensional echocardiographic measurements are major predictors of adverse cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. The protective effects of captopril. Circulation 1994; 89: 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nishino S, Watanabe N, Kimura T, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Nakama T, Furugen M, Koiwaya H, Ashikaga K, Kuriyama N, Shibata Y. The course of ischemic mitral regurgitation in acute myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: from emergency room to long‐term follow‐up. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9: e004841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. St John Sutton M, Lee D, Rouleau JL, Goldman S, Plappert T, Braunwald E, Pfeffer MA. Left ventricular remodeling and ventricular arrhythmias after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2003; 107: 2577–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Funaro S, La Torre G, Madonna M, Galiuto L, Scara A, Labbadia A, Canali E, Mattatelli A, Fedele F, Alessandrini F, Crea F, Agati L, Investigators A. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic value of reverse left ventricular remodelling after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the Acute Myocardial Infarction Contrast Imaging (AMICI) multicenter study. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 566–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. St John Sutton M, Pfeffer MA, Moye L, Plappert T, Rouleau JL, Lamas G, Rouleau J, Parker JO, Arnold MO, Sussex B, Braunwald E. Cardiovascular death and left ventricular remodeling two years after myocardial infarction: baseline predictors and impact of long‐term use of captopril: information from the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) trial. Circulation 1997; 96: 3294–3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhan E, Keimig T, Xu J, Peterson E, Ding J, Wang F, Yang XP. Dose‐dependent cardiac effect of oestrogen replacement in mice post‐myocardial infarction. Exp Physiol 2008; 93: 982–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]