Abstract

Aims

Many heart transplant recipients will develop end‐stage renal disease in the post‐operative course. The aim of this study was to identify the long‐term incidence of end‐stage renal disease, determine its risk factors, and investigate what subsequent therapy was associated with the best survival.

Methods and results

A retrospective, single‐centre study was performed in all adult heart transplant patients from 1984 to 2016. Risk factors for end‐stage renal disease were analysed by means of multivariable regression analysis and survival by means of Kaplan–Meier. Of 685 heart transplant recipients, 71 were excluded: 64 were under 18 years of age and seven were re‐transplantations. During a median follow‐up of 8.6 years, 121 (19.7%) patients developed end‐stage renal disease: 22 received conservative therapy, 80 were treated with dialysis (46 haemodialysis and 34 peritoneal dialysis), and 19 received a kidney transplant. Development of end‐stage renal disease (examined as a time‐dependent variable) inferred a hazard ratio of 6.45 (95% confidence interval 4.87–8.54, P < 0.001) for mortality. Tacrolimus‐based therapy decreased, and acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy increased the risk for end‐stage renal disease development (hazard ratio 0.40, 95% confidence interval 0.26–0.62, P < 0.001, and hazard ratio 4.18, 95% confidence interval 2.30–7.59, P < 0.001, respectively). Kidney transplantation was associated with the best median survival compared with dialysis or conservative therapy: 6.4 vs. 2.2 vs. 0.3 years (P < 0.0001), respectively, after end‐stage renal disease development.

Conclusions

End‐stage renal disease is a frequent complication after heart transplant and is associated with poor survival. Kidney transplantation resulted in the longest survival of patients with end‐stage renal disease.

Keywords: Dialysis, End‐stage renal disease, Heart transplantation, Kidney failure, Kidney transplantation

1. Introduction

The incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) after heart transplantation (HT) is high with percentages up to 80% reported in some studies.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 In a recent study, 19% of the 268 HT recipients developed end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) during a median follow‐up of 76 months.7 Risk factors for the development of CKD after HT include the type of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) used and the presence of comorbidities.2, 3, 8, 9

Estimating the true incidence of ESRD after HT and its effect on patient outcome is complicated by the fact that the definition of ESRD differed between studies. The definitions used in the literature can be as broad as a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) ≤ 45 mL/min/1.73 m2. Other studies only took patients who received renal replacement therapy (RRT), either dialysis and/or kidney transplantation into consideration. A small overview of ESRD definitions used is provided in Supporting Information, Table S1 . However, according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD guidelines, ESRD is defined as an estimated GFR (eGFR) ≤ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or the need for RRT.10 Moreover, HT recipients with ESRD who were treated conservatively were not included. In several studies, the survival of patients who received a kidney transplant (KT) after HT was compared with the survival of KT or simultaneous kidney and heart transplant recipients.11, 12, 13 There is only one study that compared dialysis with KT, demonstrating a survival benefit associated with KT.7

The purpose of this study was to investigate the long‐term incidence of ESRD in a large cohort of HT recipients, determine risk factors for ESRD, and investigate the effect of ESRD on survival. Furthermore, the effect of different modalities of RRT on long‐term survival was analysed.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient cohort

In this retrospective study, all adult patients who received an HT at the Erasmus MC between June 1984 and May 2016 were included. The investigation conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.14 The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Review Committee of the Erasmus MC (MEC‐2017‐421). When a patient had a re‐transplantation, only the first HT was included. When re‐transplanted, the patient was censored at the date of the second transplantation.

2.2. Pre‐operative kidney function

An eGFR of 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 before HT is normally an absolute contraindication for HT. However, this is only the case when a patient has a decreased kidney function because of a renal disease. When a patient has a decreased eGFR, we test for reversibility in order to exclude pre‐renal insufficiency, which is frequently encountered in heart failure patients who are on the waiting list. When reversibility is demonstrated (by inotropic ± temporary mechanical support), the patient can still be listed for transplantation. To monitor kidney function before HT, proteinuria is monitored frequently in order to see whether a patient develops a kidney disease (such as hypertensive or diabetic nephropathy).

2.3. Post‐transplantation immunosuppressive regimen

The immunosuppressive regimen used at our centre was described previously.15, 16 Until 2000, maintenance immunosuppression consisted of ciclosporin (CsA) in combination with prednisone. If patients experienced rejection, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil was added. After 2000, CsA was replaced by tacrolimus as the CNI of choice.

2.4. Comorbidity after heart transplantation

Kidney function was classified according to the 2012 KDIGO CKD evaluation guidelines and the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines.10, 17 ESRD (CKD Stage 5) was defined as an eGFR ≤ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or when a patient received RRT. RRT was defined as treatment with dialysis (haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) or a KT. Patients who declined dialysis and/or KT or who were not deemed fit for dialysis or KT were considered as patients who received conservative therapy.

Data on kidney function were collected before HT (considered as baseline), at Month 12 after HT, and then annually. Estimated GFR was calculated with the CKD‐EPI method.18 In addition, demographic and (pre‐HT) clinical characteristics were collected from the electronic patient files and from our electronic database. Patients were seen at the Erasmus MC at least twice a year.

Patients who developed acute on chronic renal failure within the first year but improved (within the first post‐transplant year) were not classified as having ESRD. Rather, these patients were classified based on their eGFR at Year 1 and the corresponding CKD stage.

Patients were considered to have diabetes mellitus when they used any kind of glucose‐lowering drug at the time of HT. Post‐transplantation diabetes mellitus was diagnosed whenever a patient developed the need for any such drug after HT, and this need persisted for more than 3 months.

Hypertension was defined according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines.19

All patients had a coronary angiogram routinely performed at Years 1 and 4 after HT. After 4 years, patients underwent a stress myocardial perfusion imaging annually. When any abnormalities were observed, the patient underwent coronary angiography. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) was defined according the 2010 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) guideline.20

2.5. Statistical analysis

The distribution of continuous variables was examined for normality by means of histograms and skewness coefficients. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and non‐normally distributed variables as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Associations between baseline characteristics and occurrence of ESRD and mortality were examined by means of Cox regression. Patients lost to follow‐up were considered at risk until the date of last contact, at which time point they were censored. Moreover, to account for the fact that patients treated with tacrolimus were unable to reach follow‐up times as long as those of CsA‐treated patients, follow‐up was censored at 15 years for all patients for this analysis. The Cox proportional hazards assumption was assessed by means of log–log plots. First, univariable Cox models were used. Subsequently, a multivariable analysis was performed with variables with a threshold P‐value ≤ 0.1.

In the setting of our study, the main event of interest, ESRD, could have been precluded by death. In that case, Kaplan–Meier curves overestimate the incidence of the outcome and Cox regression models may inflate the relative differences between the groups resulting in biased hazard ratios (HRs).21 Therefore, in order to further verify the association between baseline characteristics and ESRD, the analysis of competing risks was performed with ESRD as event of interest and death as competing event according to a model proposed by Fine and Gray.22 We present subdistribution HRs from the multivariable Fine and Gray model.

To investigate the risk of death associated with the development of ESRD during follow‐up, ESRD was entered into an extended Cox model as a time‐dependent variable.

In patients who developed ESRD, univariable Cox models were used to examine associations between clinical characteristics and KT. To examine the effect of RRT modalities on survival, the cumulative event rates per RRT modality were estimated according to the Kaplan–Meier method. Kaplan–Meier event curves were compared by log‐rank tests.

Analyses were performed using statistical software SPSS, Version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., IBM Company, Chicago, IL), R Statistical Software, Version 3.5.2 (package ‘cmprsk'), and GraphPad Prism, Version 5.0a (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

3. Results

From June 1984 to May 2016, 685 HTs were performed in 678 patients. Of these 685 transplantations, 71 were excluded from the present analysis: 64 patients were aged under 18 years at the time of transplantation and seven were re‐transplantations. The characteristics of the included 614 patients are described in Table 1. Before 2000, 351 patients were transplanted, and after 2000 (the year when tacrolimus became the CNI of choice at our centre), 263 were transplanted. The median follow‐up of all patients was 8.6 years (IQR 4.0–14.0).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all patients and a comparison between patients with and without ESRD

| Parameter | All patients (n = 614) | HT without ESRD (n = 493) | HT with ESRD (n = 121) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.0 [43.0–56.3] | 51.0 [43.0–57.0] | 49.0 [42.0–55.0] |

| Male gender | 462 (75) | 362 (73) | 100 (83) |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 564 (92) | 449 (91) | 115 (95) |

| eGFR at HT | 63 ± 23 | 63 ± 23 | 61 ± 22 |

| CKD stage before HT | |||

| CKD Stage 1 | 78 (13) | 65 (13) | 13 (11) |

| CKD Stage 2 | 244 (40) | 195 (40) | 49 (40) |

| CKD Stage 3a | 160 (26) | 130 (26) | 30 (25) |

| CKD Stage 3b | 101 (16) | 76 (15) | 25 (21) |

| CKD Stage 4 | 30 (5) | 26 (5) | 4 (3) |

| CKD Stage 5 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Heart failure aetiology | |||

| Ischaemic CMP | 299 (49) | 235 (48) | 64 (53) |

| Non‐ischaemic CMP | 315 (51) | 258 (52) | 57 (47) |

| Diabetes mellitus before HT | 41 (7) | 34 (7) | 7 (6) |

| MCS before HT | 84 (14) | 69 (14) | 15 (12) |

| Type of MCS | |||

| IABP | 45 (7) | 32 (6) | 13 (11) |

| LVAD | 34 (6) | 34 (7) | 0 (0) |

| ECMO | 3 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (2) |

| BIVAD | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| AKI requiring RRT | 54 (9) | 40 (8) | 14 (12) |

| CsA‐based therapy | 303 (49) | 219 (44) | 84 (69) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; BIVAD, biventricular assist device; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMP, cardiomyopathy; CsA, ciclosporin; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in mL/min/1.73 m2); ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; HT, heart transplantation; IABP, intra‐aortic balloon pump; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MCS, mechanical support; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Categorical variables are presented as %. Normally distributed continuous variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Non‐normally distributed continuous variables are shown as a median with [interquartile range].

3.1. End‐stage renal disease after heart transplantation

During follow‐up, 121 (19.7%) patients developed ESRD. The median time between HT and development of ESRD was 7.7 years (IQR 5.0–10.7). ESRD‐free survival at 1, 5, and 10 years of follow‐up was 86%, 76%, and 53%, respectively. ESRD occurred more frequently in male than in female patients (Table 1). One patient had CKD Stage 5 before HT but did not develop ESRD after transplantation. This patient had an eGFR around 70 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the year before HT until the patient developed severe forward failure and needed inotropic and mechanical support before HT. The patient was transplanted urgently. After HT, the eGFR normalized to 73 mL/min/1.73 m2.

In total, 80 patients were treated with dialysis only: 46 with haemodialysis and 34 with peritoneal dialysis. Nineteen patients underwent a KT. One of these 19 patients received a second KT. Only data on the first KT were included in the present analysis. Twenty‐two patients were treated conservatively. These patients either declined or were considered too frail for RRT. In more detail, five (22.7%) patients had cardiac comorbidities, 11 (50%) patients had non‐cardiac comorbidities, four (18.2%) patients were not willing to undergo RRT, one (4.5%) patient died before the RRT could be initiated, and one (4.5%) patient was still being screened for RRT at the end of follow‐up.

3.2. Timing of development of end‐stage renal disease after heart transplantation

Of the 121 patients who developed ESRD, 30 developed ESRD within the first 5 years after HT, 58 between 5 and 10 years, and 33 after 10 years. In Table 2, the baseline characteristics before HT are shown according to the timing of ESRD development. A higher eGFR before HT was associated with a later onset of ESRD. Heart failure aetiology or the presence of diabetes mellitus before HT was not associated with the timing of ESRD development. AKI requiring RRT was associated with an increased risk to develop ESRD (in both the short term and the long term). Causes of AKI after HT could be divided into one of the following categories: the haemodynamic insult of the transplant surgery, pre‐renal kidney insufficiency due to heart failure, the introduction of immunosuppression after HT, and other complications after HT like rejection or infection. Specific percentages cannot be given, as a combination of factors eventually leads to AKI after HT. CsA‐based therapy increased the risk to develop ESRD in the long term [HR 2.36 (1.55–3.60); P < 0.001]. Tacrolimus‐based treatment reduced this risk significantly [HR 0.43 (0.28–0.65); P < 0.001].

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to time of ESRD development

| Parameter | All patients (n = 614) | All ESRD patients (n = 121) | ESRD 0–5 years (n = 30) | ESRD 0–10 years (n = 88) | ESRD 0–15 years (n = 108) | Hazard ratio 0–5 years (95% CI) | Hazard ratio 0–10 years (95% CI) | Hazard ratio 0–15 years (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.0 [43.0–56.3] | 49.0 [42.0–55.0] | 49.0 [41.8–53.0] | 49.0 [42.3–55.0] | 50.0 [43.3–55.0] | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) |

| Male gender | 462 (75) | 100 (83) | 27 (90) | 78 (89) | 91 (84) | 2.81 (0.85–9.25) | 2.55 (1.32–4.93)* | 1.73 (1.03–2.90)* |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 564 (92) | 115 (95) | 28 (93) | 85 (97) | 104 (96) | 1.23 (0.29–5.15) | 2.17 (0.69–6.88) | 1.95 (0.72–5.30) |

| eGFR at HT | 63 ± 23 | 61 ± 22 | 56 ± 21 | 61 ± 22 | 59 ± 21 | 0.98 (0.97–1.00) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00)* |

| CKD stage before HT | 1.30 (0.94–1.79) | 1.11 (0.91–1.36) | 1.21 (1.01–1.44)* | |||||

| CKD Stage 1 | 78 (13) | 13 (11) | 3 (10) | 11 (13) | 11 (10) | 1.00a | 1.00a | 1.00a |

| CKD Stage 2 | 244 (40) | 49 (40) | 8 (27) | 34 (39) | 42 (39) | 0.84 (0.22–3.15) | 0.90 (0.45–1.77) | 1.12 (0.58–2.18) |

| CKD Stage 3a | 160 (26) | 30 (25) | 10 (33) | 21 (24) | 26 (24) | 1.76 (0.48–6.39) | 0.92 (0.45–1.91) | 1.15 (0.57–2.33) |

| CKD Stage 3b | 101 (16) | 25 (21) | 8 (27) | 20 (23) | 25 (23) | 2.30 (0.61–8.66) | 1.66 (0.80–3.47) | 2.17 (1.07–4.41)* |

| CKD Stage 4 | 30 (5) | 4 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 1.02 (0.11–9.82) | 0.62 (0.14–2.79) | 1.31 (0.42–4.12) |

| CKD Stage 5 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | — | — |

| Heart failure aetiology | 0.94 (0.46–1.93) | 1.18 (0.78–1.80) | 1.27 (0.87–1.85) | |||||

| Ischaemic CMP | 299 (49) | 64 (53) | 14 (47) | 46 (52) | 58 (54) | |||

| Non‐ischaemic CMP | 315 (51) | 57 (47) | 16 (53) | 42 (48) | 50 (46) | |||

| MCS before HT | 84 (14) | 15 (12) | 4 (13) | 12 (14) | 15 (14) | 1.10 (0.38–3.16) | 1.36 (0.74–2.51) | 1.46 (0.84–2.52) |

| CsA‐based therapy | 303 (49) | 84 (69) | 19 (63) | 63 (72) | 78 (72) | 1.62 (0.77–3.39) | 2.32 (1.46–3.68)* | 2.36 (1.55–3.60)* |

| Tacrolimus‐based therapy | 283 (46) | 37 (31) | 11 (37) | 25 (28) | 30 (28) | 0.62 (0.30–1.31) | 0.44 (0.28–0.69)* | 0.43 (0.28–0.65)* |

| Diabetes mellitus before HT | 41 (7) | 7 (6) | 1 (3) | 6 (7) | 7 (7) | 0.51 (0.07–3.72) | 1.21 (0.53–2.78) | 1.26 (0.59–2.72) |

| AKI requiring RRT | 54 (9) | 14 (12) | 10 (33) | 13 (15) | 14 (13) | 8.84 (4.12–18.98)* | 3.94 (2.18–7.12)* | 3.83 (2.17–6.75)* |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMP, cardiomyopathy; CsA, ciclosporin; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in mL/min/1.73 m2); ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; HT, heart transplantation; MCS, mechanical support; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Categorical variables are presented as %. Normally distributed continuous variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Non‐normally distributed continuous variables are shown as a median with [interquartile range]. Results of univariable Cox regression analysis are shown with hazard ratio (CIs).

Reference.

P < 0.05.

3.3. Post‐transplant complications

After HT, 498 (81%) patients had hypertension and 144 (24%) developed post‐transplantation diabetes mellitus. Hypertension was more frequently present in patients with ESRD than those who did not develop ESRD (89.3% vs. 79.1%, respectively, P = 0.011). In total, 259 (42%) patients developed CAV. Patients that developed ESRD had more frequently CAV than patients without ESRD: 70 (58%) vs. 189 (38%) patients; P < 0.001.

3.4. Survival after heart transplantation in relation to end‐stage renal disease

The overall median long‐term survival of the cohort after HT was 11.7 years (IQR 10.7–12.7). The extended Cox regression analysis with ESRD entered as a time‐dependent variable demonstrated an HR of 6.45 (95% CI 4.87–8.54, P < 0.001) for mortality when corrected for age, eGFR at HT, heart failure aetiology, CsA‐based therapy and AKI requiring RRT.

3.5. Kidney after heart transplantation

In total, 19 patients received a KT. Five patients received a kidney from a deceased donor and 14 patients from a living donor. Of these 14 living donors, seven were related and seven were unrelated donors. Four patients received a pre‐emptive KT, and 15 were treated with dialysis first. In Table 3, the baseline characteristics of these 19 patients are presented. The median time between HT and ESRD was shorter in patients who received a KT compared with patients who did not (7.1 vs. 8.7 years, P < 0.0001). The median time between HT and KT was 8.0 years (IQR 4.8–12.1). The median time between the development of ESRD and KT was 1.5 years (IQR 0.7–2.7).

Table 3.

Characteristics of heart transplant patients who received a KT vs. those who did not

| Parameter | All ESRD patients (n = 121) | KT (n = 19) | No KT (n = 102) | Hazard ratio | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.0 [42.0–55.0] | 45.0 [41.0–52.0] | 50.0 [44.8–55.0] | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.73 |

| Male gender | 100 (83) | 17 (89) | 83 (81) | 1.63 (0.37–7.20) | 0.52 |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 115 (95) | 17 (89) | 98 (96) | 0.26 (0.05–1.28) | 0.10 |

| eGFR at HT | 61 ± 22 | 59 ± 23 | 61 ± 22 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.21 |

| CKD stage before HT | 1.41 (0.91–2.19) | 0.12 | |||

| CKD Stage 1 | 13 (11) | 3 (16) | 10 (10) | 1.00a | |

| CKD Stage 2 | 49 (40) | 5 (26) | 44 (43) | 0.50 (0.11–2.37) | 0.38 |

| CKD Stage 3a | 30 (25) | 4 (21) | 26 (25) | 2.43 (0.50–11.80) | 0.27 |

| CKD Stage 3b | 25 (21) | 7 (37) | 18 (18) | 1.64 (0.40–6.74) | 0.49 |

| CKD Stage 4 | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | — | — |

| CKD Stage 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | — |

| Time from HT to ESRD (years) | 7.7 [5.0–10.7] | 5.9 [2.3–8.9] | 7.9 [5.8–10.9] | 0.68 (0.56–0.83) | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure aetiology | 0.84 (0.33–2.15) | 0.72 | |||

| Ischaemic CMP | 64 (53) | 10 (53) | 54 (53) | ||

| Non‐ischaemic CMP | 57 (47) | 9 (47) | 48 (47) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus before HT | 7 (6) | 2 (11) | 5 (5) | 1.14 (0.25–5.10) | 0.87 |

| MCS before HT | 15 (12) | 3 (16) | 12 (12) | 1.11 (0.30–4.08) | 0.87 |

| AKI requiring RRT | 14 (12) | 5 (26) | 9 (9) | 12.71 (2.88–56.13) | 0.001 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMP, cardiomyopathy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in mL/min/1.73 m2); ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; HT, heart transplantation; KT, kidney transplantation; MCS, mechanical support; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Categorical variables are presented as %. Normally distributed continuous variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Non‐normally distributed continuous variables are shown as a median with [interquartile range]. Results of univariable Cox regression analysis are shown with hazard ratios (CIs).

Reference.

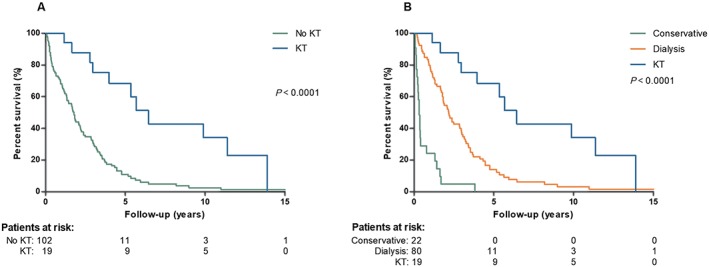

Figure 1 A depicts the survival of patients who underwent a KT compared with patients who did not from the time of ESRD diagnosis. The survival of patients with ESRD who received a KT was significantly better than patients who did not (P < 0.0001). When the group of patients who did not receive a KT was divided into a conservative and a dialysis group, the same pattern was observed: KT resulted in the best survival [median 6.4 years (IQR 4.7–8.2)], followed by dialysis [median 2.2 years (IQR 1.7–2.7)] and conservative therapy [median 0.3 years (IQR 0.2–0.4)]; P < 0.0001 (Figure 1 B).

Figure 1.

(A) Survival curve after the development of end‐stage renal disease of patients receiving a kidney transplant (KT) vs. no KT. (B) Survival curve after development of end‐stage renal disease of patients receiving a KT vs. dialysis vs. conservative therapy.

Patients who received a KT from a living donor had a better survival compared with those who received a KT from a deceased donor (P = 0.02; Supporting Information, Figure S 1 A). Among recipients of a living donor KT, a living‐related donor resulted in a better survival than a living‐unrelated donor (P = 0.02; Supporting Information, Figure S 1 B).

3.6. Predictors for end‐stage renal disease and mortality

The Cox proportional hazard assumption was met for all variables entered into the multivariable model. In Cox regression analysis, AKI requiring RRT gave a significantly higher risk for ESRD [HR 4.18 (2.30–7.59, P < 0.001)], while tacrolimus‐based therapy decreased the risk to develop ESRD [HR 0.40 (0.26–0.62, P < 0.001)]. Male gender and eGFR at HT were not associated with a higher risk of ESRD. The competing risk analysis (Fine and Gray model) did not alter these associations (Table 4). For mortality, age gave an increased risk of mortality of 1.02 (1.00–1.04, P = 0.002) per year (Table 5). Ischaemic heart failure before HT was associated with an increased risk of mortality after HT of 1.36 (1.04–1.80, P = 0.02). Furthermore, AKI requiring RRT gave an increased risk for mortality after HT: HR 2.79 (1.68–4.61, P < 0.001), while tacrolimus‐based therapy decreased the risk (in comparison with CsA): [HR 0.35 (0.26–0.48, P < 0.001)]. Estimated GFR at HT was not a predictor of mortality after HT.

Table 4.

Risk prediction for end‐stage renal disease

| Covariate | Cox model | Fine and Gray model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P‐value | SHR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| Male gender | 1.59 | 0.93–2.69 | 0.08 | 1.67 | 0.99–2.81 | 0.05 |

| eGFR at HT | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.11 |

| Tac‐based therapy | 0.40 | 0.26–0.62 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.36–0.83 | 0.004 |

| AKI requiring RRT | 4.18 | 2.30–7.59 | <0.001 | 2.48 | 1.33–4.62 | 0.004 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in mL/min/1.73 m2); HR, hazard ratio; HT, heart transplantation; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; Tac, tacrolimus.

HRs from multivariable Cox model and SHRs from multivariable Fine and Gray model for mortality.

Table 5.

Risk prediction for mortality

| Covariate | Cox model | Fine and Gray model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P‐value | SHR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| Age (years) | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.002 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.04 | <0.001 |

| eGFR at HT | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.39 |

| Ischaemic CMP | 1.36 | 1.04–1.80 | 0.02 | 1.33 | 1.01–1.74 | 0.04 |

| Tac‐based therapy | 0.35 | 0.26–0.48 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.28–0.52 | <0.001 |

| AKI requiring RRT | 2.79 | 1.68–4.61 | <0.001 | 2.13 | 1.24–3.62 | 0.005 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; CMP, cardiomyopathy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in mL/min/1.73 m2); HR, hazard ratio; HT, heart transplantation; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; Tac, tacrolimus.

HRs from multivariable Cox model and SHRs from multivariable Fine and Gray model for mortality.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that ESRD is a frequent complication of HT and is associated with a more than six‐fold increased risk of death compared with patients who do not develop ESRD. This is in line with other studies.2, 3 In the multivariable analysis, CsA‐based therapy (in comparison with tacrolimus‐based therapy) and AKI requiring RRT were independent risk factors for ESRD development. Patients who received a kidney‐after‐heart transplant had a better survival compared with ESRD patients who were treated with dialysis or conservative therapy. Living donor KT resulted in a better survival compared with deceased donor KT.

The long‐term incidence of ESRD after HT in this study (19.7%) is comparable with the incidence found by Grupper et al.7 who reported an incidence of 19% in a cohort of 268 patients. The 2017 ISHLT Registry Report reports an incidence of severe renal dysfunction (defined as the development of a serum creatinine ≥221 μmol/L, chronic dialysis, or renal transplant within 10 years) of 29.2% among 8261 HT recipients of whom 10.5% received chronic dialysis or renal transplant.23 In comparison with Grupper et al., we used the KDIGO criteria to define ESRD, which encompasses a wider range of renal insufficiency. Furthermore, our median follow‐up time was significantly longer (103 vs. 76 months, respectively). The median time between HT and the development ESRD in our study was 92 months (IQR 59–128), which was longer compared with other studies. Both Grupper et al. and Cassuto et al.7, 13 noticed a shorter onset of ESRD after HT (83 and 65 months, respectively). This implies that the renal function of our patients was better and longer preserved in comparison with other studies. As renal failure remains one of the Achilles' heels of the survival after HT, a nephrologist has participated in the HT team since the start of our programme. Monitoring proteinuria is now an integral part of our post‐HT surveillance and is recommended by both KDIGO and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines.10, 17

Ciclosporin was an independent predictor of ESRD in our study, conforming the results of earlier studies.1, 2 In addition to reducing the incidence of acute rejection, this is an important advantage of tacrolimus over CsA. Furthermore, AKI requiring RRT was a predictor for both ESRD and mortality. This is in line with studies of Fortrie et al. and Ojo et al..2, 15 The fact that we added a competing risk analysis to our study strengthens the result found in this study.

The exact reason why patients develop ESRD after transplant is unknown. Many factors play a role in the deterioration of kidney function after transplantation. AKI is one of the factors leading to ESRD in HT recipients.15 In a recent review by Fortrie et al.24 on the relationship between AKI and ESRD, this is further discussed. Normally, the kidney is capable to repair damaged tissue and has enough residual function. In patients with pre‐existing comorbidities (i.e. hypertension or diabetes mellitus), this capacity is diminished. When these patients develop AKI, inflammatory cytokines are activated, leading to hyperfiltration. This can promote glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis and finally ESRD.24 Furthermore, the use of CNIs (CsA and tacrolimus) has deleterious effects on the kidney function as demonstrated in this manuscript. Further research is needed to understand the causes of ESRD in HT patients in order to develop therapeutic or even preventive options for this patient group.

One question that may arise in the light of our results is whether combined kidney–HT (KHT) is an option for patients with compromised kidney function (or even renal failure) and whether this will result in less ESRD in the long term. Several studies (both single‐centre and national) have demonstrated a good survival after KHT.25, 26, 27, 28 In some studies using the United Network for Organ Sharing database, there was even a survival benefit for patients undergoing combined KHT in comparison with HT alone.26, 27 Even though these studies suggest a benefit of combined KHT (although all studies have a maximum follow‐up of around 6 years), this type of transplant is not performed in the Netherlands due to the shortage of suitable donors.

This study has several limitations. First of all, it is a single‐centre study with a low number of KT after HT. Second, better survival in patients treated with KT may be influenced by selection bias. Patients who develop ESRD early are usually less frail compared with patients who develop ESRD longer after HT (although not measured and described). This selection bias is something present in daily practice, where the best patients are considered suitable candidates for KT. Third, the association between the risk of ESRD and CsA or tacrolimus exposure was not analysed in this study. Patients with a high CNI exposure may have had an increased risk to develop ESRD as a result of the drugs' nephrotoxicity. However, in clinical practice, in patients with an impaired renal function, the CNI dose is often decreased, which could result in the paradoxical finding that HT recipients with the worst renal function actually have the lowest exposure to CNI, suggesting that these drugs are nephroprotective. Fourth, kidney biopsies are not routinely performed in our centre. However, all patients with CKD following HT are seen by a nephrologist to aid in diagnosing the cause of the renal insufficiency and help limit the deterioration of the renal function.

In conclusion, ESRD is a frequently occurring long‐term complication of HT. Patients who develop ESRD have a worse survival than patients who do not develop ESRD. CsA‐based therapy and AKI requiring RRT were independent risk factors for the development of ESRD. When patients developed ESRD, KT, preferably from a living donor, gave a better survival than dialysis or conservative therapy.

Conflict of interest

D.A.H. has received lecture and consulting fees from Astellas Pharma and Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., as well as grant support (paid to the Erasmus MC) from Astellas Pharma, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A. None of the other authors have a conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Survival curve of KT recipients receiving a kidney of a deceased donor vs. a living donor (Supp. 1A); Survival curve of KT recipients receiving a kidney of a deceased donor vs. a living‐unrelated donor vs. a living‐related donor (Supp. 1B).

Table S1. Definitions end‐stage renal disease in literature

Roest, S. , Hesselink, D. A. , Klimczak‐Tomaniak, D. , Kardys, I. , Caliskan, K. , Brugts, J. J. , Maat, A. P. W. M. , Ciszek, M. , Constantinescu, A. A. , and Manintveld, O. C. (2020) Incidence of end‐stage renal disease after heart transplantation and effect of its treatment on survival. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 533–541. 10.1002/ehf2.12585.

References

- 1. van Gelder T, Balk AH, Zietse R, Hesse C, Mochtar B, Weimar W. Renal insufficiency after heart transplantation: a case–control study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998. Sep; 13: 2322–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ojo AO, Held PJ, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Leichtman AB, Young EW, Arndorfer J, Christensen L, Merion RM. Chronic renal failure after transplantation of a nonrenal organ. N Engl J Med 2003. Sep 04; 349: 931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas HL, Banner NR, Murphy CL, Steenkamp R, Birch R, Fogarty DG, Bonser AR. Steering Group of the UKCTA. Incidence, determinants, and outcome of chronic kidney disease after adult heart transplantation in the United Kingdom. Transplantation 2012. Jun 15; 93: 1151–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gonzalez‐Vilchez F, Arizon JM, Segovia J, Almenar L, Crespo‐Leiro MG, Palomo J, Delgado JF, Mirabet S, Rabago G, Perez‐Villa F, Diaz B, Sanz ML, Pascual D, de la Fuente L, Guinea G, Group IS . Chronic renal dysfunction in maintenance heart transplant patients: the ICEBERG study. Transplant Proc 2014. Jan‐Feb; 46: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Soderlund C, Lofdahl E, Nilsson J, Reitan O, Higgins T, Radegran G. Chronic kidney disease after heart transplantation: a single‐centre retrospective study at Skåne University Hospital in Lund 1988–2010. Transpl Int 2016. May; 29: 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen YC, Chou NK, Hsu RB, Chi NH, Wu IH, Chen YS, Yu HY, Huang SC, Wang CH, Tsao CI, Ko WJ, Wang SS. End‐stage renal disease after orthotopic heart transplantation: a single‐institute experience. Transplant Proc 2010. Apr; 42: 948–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grupper A, Grupper A, Daly RC, Pereira NL, Hathcock MA, Kremers WK, Cosio FG, Edwards BS, Kushwaha SS. Kidney transplantation as a therapeutic option for end‐stage renal disease developing after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017. Mar; 36: 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al Aly Z, Abbas S, Moore E, Diallo O, Hauptman PJ, Bastani B. The natural history of renal function following orthotopic heart transplant. Clin Transplant 2005. Oct; 19: 683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kolsrud O, Karason K, Holmberg E, Ricksten SE, Felldin M, Samuelsson O, Dellgren G. Renal function and outcome after heart transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018. Apr; 155: 1593–1604 e1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group . KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013; 3: 1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coopersmith CM, Brennan DC, Miller B, Wang C, Hmiel P, Shenoy S, Ramachandran V, Jendrisak MD, Ceriotti CS, Mohanakumar T, Lowell JA. Renal transplantation following previous heart, liver, and lung transplantation: an 8‐year single‐center experience. Surgery 2001. Sep; 130: 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lonze BE, Warren DS, Stewart ZA, Dagher NN, Singer AL, Shah AS, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Kidney transplantation in previous heart or lung recipients. Am J Transplant 2009. Mar; 9: 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cassuto JR, Reese PP, Bloom RD, Doyle A, Goral S, Naji A, Abt PL. Kidney transplantation in patients with a prior heart transplant. Transplantation 2010. Feb 27; 89: 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rickham PP. Human experimentation. Code of ethics of the World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Br Med J 1964; 2: 177–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fortrie G, Manintveld OC, Constantinescu AA, van de Woestijne PC, Betjes MGH. Renal function at 1 year after cardiac transplantation rather than acute kidney injury is highly associated with long‐term patient survival and loss of renal function—a retrospective cohort study. Transpl Int 2017. Aug; 30: 788–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zijlstra LE, Constantinescu AA, Manintveld O, Birim O, Hesselink DA, van Thiel R, van Domburg R, Balk AH, Caliskan K. Improved long‐term survival in Dutch heart transplant patients despite increasing donor age: the Rotterdam experience. Transpl Int 2015. Aug; 28: 962–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182 (1 February 2017) [PubMed]

- 18. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD EPI . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009. May 05; 150: 604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Redon J, Dominiczak A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson PM, Burnier M, Viigimaa M, Ambrosioni E, Caufield M, Coca A, Olsen MH, Schmieder RE, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Clement DL, Coca A, Gillebert TC, Tendera M, Rosei EA, Ambrosioni E, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Hitij JB, Caulfield M, De Buyzere M, De Geest S, Derumeaux GA, Erdine S, Farsang C, Funck‐Brentano C, Gerc V, Germano G, Gielen S, Haller H, Hoes AW, Jordan J, Kahan T, Komajda M, Lovic D, Mahrholdt H, Olsen MH, Ostergren J, Parati G, Perk J, Polonia J, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Ryden L, Sirenko Y, Stanton A, Struijker‐Boudier H, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Vlachopoulos C, Volpe M, Wood DA. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013. Jul; 34: 2159–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehra MR, Crespo‐Leiro MG, Dipchand A, Ensminger SM, Hiemann NE, Kobashigawa JA, Madsen J, Parameshwar J, Starling RC, Uber PA. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation working formulation of a standardized nomenclature for cardiac allograft vasculopathy—2010. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010. Jul; 29: 717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation 2016. Feb 9; 133: 601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94: 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lund LH, Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb S, Kucheryavaya AY, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Chambers DC, Yusen RD, Stehlik J. International Society for H, Lung T. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty‐fourth adult heart transplantation report—2017; focus theme: allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017. Oct; 36: 1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fortrie G, de Geus HRH, Betjes MGH. The aftermath of acute kidney injury: a narrative review of long‐term mortality and renal function. Crit Care 2019. Jan 24; 23: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grupper A, Grupper A, Daly RC, Pereira NL, Hathcock MA, Kremers WK, Cosio FG, Edwards BS, Kushwaha SS. Renal allograft outcome after simultaneous heart and kidney transplantation. Am J Cardiol 2017. Aug 1; 120: 494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kilic A, Grimm JC, Whitman GJ, Shah AS, Mandal K, Conte JV, Sciortino CM. The survival benefit of simultaneous heart–kidney transplantation extends beyond dialysis‐dependent patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2015. Apr; 99: 1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karamlou T, Welke KF, McMullan DM, Cohen GA, Gelow J, Tibayan FA, Mudd JM, Slater MS, Song HK. Combined heart–kidney transplant improves post‐transplant survival compared with isolated heart transplant in recipients with reduced glomerular filtration rate: analysis of 593 combined heart–kidney transplants from the United Network Organ Sharing Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014. Jan; 147: 456–461 e451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reich H, Dimbil S, Levine R, Megna D, Mersola S, Patel J, Kittleson M, Czer L, Kobashigawa J, Esmailian F. Dual‐organ transplantation in older recipients: outcomes after heart–kidney transplant versus isolated heart transplant in patients aged ≥65 years. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019. Jan 1; 28: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hendawy A, Pouteil‐Noble C, Villar E, Boissonnat P, Sebbag L. Chronic renal failure and end‐stage renal disease are associated with a high rate of mortality after heart transplantation. Transplant Proc 2005. Mar; 37: 1352–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alam A, Badovinac K, Ivis F, Trpeski L, Cantarovich M. The outcome of heart transplant recipients following the development of end‐stage renal disease: analysis of the Canadian Organ Replacement Register (CORR). Am J Transplant 2007. Feb; 7: 461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Survival curve of KT recipients receiving a kidney of a deceased donor vs. a living donor (Supp. 1A); Survival curve of KT recipients receiving a kidney of a deceased donor vs. a living‐unrelated donor vs. a living‐related donor (Supp. 1B).

Table S1. Definitions end‐stage renal disease in literature