Abstract

Aims

Current guidelines recommend sacubitril/valsartan for patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), but there is lack of evidence of its efficacy and safety in cancer therapy‐related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD). Our aim was to analyse the potential benefit of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with CTRCD.

Methods and results

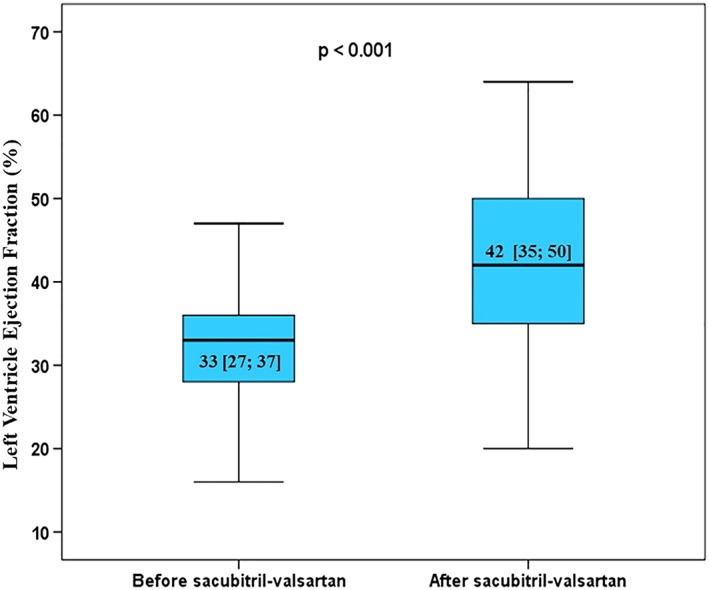

We performed a retrospective multicentre registry (HF‐COH) in six Spanish hospitals with cardio‐oncology clinics including all patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan. Demographic and clinical characteristics and laboratory and echocardiographic data were collected. Median follow‐up was 4.6 [1; 11] months. Sixty‐seven patients were included (median age was 63 ± 14 years; 64% were female, 87% had at least one cardiovascular risk factor). Median time from anti‐cancer therapy to CTRD was 41 [10; 141] months. Breast cancer (45%) and lymphoma (39%) were the most frequent neoplasm, 31% had metastatic disease, and all patients were treated with combination antitumor therapy (70% with anthracyclines). Thirty‐nine per cent of patients had received thoracic radiotherapy. Baseline median LVEF was 33 [27; 37], and 21% had atrial fibrillation. Eighty‐five per cent were on beta‐blocker therapy and 76% on mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; 90% of the patients were symptomatic NYHA functional class ≥II. Maximal sacubitril/valsartan titration dose was achieved in 8% of patients (50 mg b.i.d.: 60%; 100 mg b.i.d.: 32%). Sacubitril/valsartan was discontinued in four patients (6%). Baseline N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide levels (1552 pg/mL [692; 3624] vs. 776 [339; 1458]), functional class (2.2 ± 0.6 vs. 1.6 ± 0.6), and LVEF (33% [27; 37] vs. 42 [35; 50]) improved at the end of follow‐up (all P values ≤0.01). No significant statistical differences were found in creatinine (0.9 mg/dL [0.7; 1.1] vs. 0.9 [0.7; 1.1]; P = 0.055) or potassium serum levels (4.5 mg/dL [4.1; 4.8] vs. 4.5 [4.2; 4.8]; P = 0.5). Clinical, echocardiographic, and biochemical improvements were found regardless of the achieved sacubitril–valsartan dose (low or medium/high doses).

Conclusions

Our experience suggests that sacubitril/valsartan is well tolerated and improves echocardiographic functional and structural parameters, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide levels, and symptomatic status in patients with CTRCD.

Keywords: Cancer, Cardio‐oncology, Cardiotoxicity, Heart failure, Sacubitril–valsartan

Background

Cancer therapy‐related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) is a complication of growing interest because of its potentially serious impact on patient outcome. CTRCD has been associated with a particularly poor prognosis compared with other forms of cardiomyopathy1, 2; however, when standard medical treatment derived from clinical practice guidelines for heart failure is systematically applied, a much better prognosis is obtained, with a mortality risk similar to that of non‐ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy.3

Current guidelines and recent expert consensus of heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology4, 5 recommend sacubitril–valsartan for patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF) for further reduction of mortality and hospitalizations,6 but there is lack of evidence of its performance under real‐word conditions (effectiveness) in patients with cancer and HFrEF. Indeed, patients with a history of chemotherapy‐related HFrEF less than 12 months prior were an exclusion criterion for PARADIGM‐HF trial.6

Objective

The aim of this study was to analyse the effectiveness of sacubitril–valsartan in onco‐haematological patients with CTRCD followed by cardio‐oncology units in Spain.

Methods

We performed a retrospective multicentre registry in six Spanish hospitals with cardio‐oncology units including all cancer patients treated with sacubitril–valsartan symptomatic HFrEF [left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40%] due to cancer therapies.7 The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Investigation, University Hospital of Salamanca, Spain. Demographic and clinical characteristics including type of neoplasms and cancer treatment were obtained. Physical examination (blood pressure and heart rate) and blood samples laboratory data, including N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), potassium levels, and renal function, were collected. A transthoracic echocardiography for each participant was performed before starting sacubitril–valsartan and a median of 4.6 [1; 11] months after sacubitril–valsartan treatment.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for normal quantitative variables and as median [inter‐quartile range] for non‐normal ones. For categorical variables, data are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Paired sample t‐test and Wilcoxon signed‐rank test were used for comparison. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, Version 23.

Results

Sixty‐seven patients were included with a median age of 63 ± 14 years; 64% were female, 87% had at least one cardiovascular risk factor (54% dyslipidaemia, 43% hypertension, and 28% diabetes), and 90% were New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class ≥II (61% NYHA II, 28% III, and 1% IV).

The two most common malignancies were breast cancer (45%) and lymphoma (39%); one‐third of patients were undergoing active antineoplastic treatment, and 31% had metastatic disease. All patients were treated with combination anti‐tumour therapy with a large variety of different antineoplastic agents: 70% received anthracyclines, 60% alkylating agents, 50% antimicrotubule agents, 25% antimetabolites, 22% tyrosine kinase inhibitors, 12% anti‐HER2 humanized antibody, 6% topoisomerase inhibitors, and 3% PD‐1 inhibitors. Moreover, 39% of patients had received thoracic radiotherapy.

Median time from anti‐cancer therapy to HFrEF was 43 [10; 141] months. Median time from HFrEF to sacubitril–valsartan initiation was 13 [2; 52] months. Sacubitril–valsartan was started in 80% of patients already treated with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, 85% were on beta‐blocker therapy, and 76% on mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular pharmacological treatment: baseline and follow‐up

| Before sacubitril–valsartan (N = 67) | After sacubitril–valsartan (N = 64) | |

|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) | 53 (80%) | 0% |

| Beta‐blocker therapy | 57 (85%) | 55 (86%) |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 51 (76%) | 43 (67%) |

| Diuretics | 35 (52%) | 35 (52%) |

The lowest sacubitril–valsartan dose of 50 mg twice daily (b.i.d.) was initially prescribed in 78% of the patients, and maximal titration dose (200 mg b.i.d.) was achieved in 8% of the patients during follow‐up (60% 50 mg b.i.d. and 32% 100 mg b.i.d.). Four patients (6%) had to discontinue sacubitril–valsartan because of adverse events (two patients due to symptomatic hypotension, one renal function impairment, and one severe pruritus).

Main results data are presented in Figure 1 and Table 2. At the end of follow‐up, reverse remodelling benefits by sacubitril‐valsartan were observed: LVEF significantly improved, and both left ventricular volumes were significantly reduced compared with basal echocardiography. It is noteworthy that eight of the patients even normalized (LVEF > 53%). Furthermore, a significant reduction in NT‐proBNP levels was evident. Fifty‐six per cent of patients exhibited an improvement in the exercise tolerance at follow‐up, as indicated by the change in NYHA functional class (at the end of follow‐up: 45% of patients with NYHA I and 47% NYHA II). These clinical, echocardiographic, and biochemical improvements were found regardless of the achieved sacubitril–valsartan dose (low or medium/high doses) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Left ventricular ejection fraction before and after sacubitril‐valsartan treatment

Table 2.

Remodelling echocardiographic, clinical, and biochemical patient parameters before and after sacubitril–valsartan treatment

| Before sacubitril–valsartan | After sacubitril–valsartan | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricle end‐diastolic volume (mL) | 144 [119; 184] | 129 [107; 168] | 0.006 |

| Left ventricle end‐systolic volume (mL) | 93 [72; 128] | 73 [54; 104] | <0.001 |

| e/e´ | 13 [9; 18] | 11 [8; 15] | 0.053 |

| Global longitudinal strain (%) | −10.5 [−13; −7.3] | −12 [−15; −8] | 0.49 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 116 [106; 119] | 112 [100; 126] | 0.006 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 70 [61; 76] | 68 [60; 72] | 0.30 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 74 [65; 81] | 68 [60; 75] | 0.01 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 [0.7; 1.1] | 0.9 [0.7; 1.1] | 0.055 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 76 [64; 90] | 70 [53; 88] | 0.02 |

| Potassium serum levels (mg/dL) | 4.5 [4.1; 4.8] | 4.5 [4.2; 4.8] | 0.50 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) | 1552 [692; 3624] | 776 [339; 1458] | 0.001 |

| NYHA functional class | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Table 3.

Cardiac remodelling echocardiographic, biochemical, and clinical measurements among patients with low vs. medium/high dose of sacubitril–valsartan at follow‐up

| Low dose of sacubitril–valsartan (N = 38) | Medium/high dose of sacubitril–valsartan (N = 25) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before sacubitril–valsartan | After sacubitril–valsartan | P value | Before sacubitril–valsartan | After sacubitril–valsartan | P value | |

| LVEF (%) | 32 [26.5; 35] | 41.5 [32; 58.5] | < 0.001 | 35 [29.5; 38.5] | 45 [37; 52] | <0.001 |

| Left ventricle end‐diastolic volume (mL) | 147 [122; 183] | 134 [108; 174] | 0.048 | 142 [115; 184] | 125 [106; 152] | 0.046 |

| Left ventricle end‐systolic volume (mL) | 96 [75; 132] | 79 [56; 112] | 0.001 | 92 [71; 127.5] | 70 [49.5; 94] | 0.006 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) | 1552 [838; 6460] | 946 [320; 2658] | 0.009 | 1490 [492; 2245] | 590 [348; 1011] | 0.027 |

| NYHA functional class | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | <0.001 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 0.001 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Values are median [inter‐quartile range].

The glomerular filtrate rate decreased significantly; however, excluding the patient who discontinued sacubitril‐valsartan because of acute renal failure (Stage 2 of Acute Kidney Injury Network classification: serum creatinine increased 250% over basal), no patient reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate at follow‐up by more than 50% from baseline. In addition, there were no significant changes in serum creatinine or potassium levels.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicentre study to report strong beneficial effect of sacubitril‐valsartan on reverse remodelling, LVEF, and NT‐proBNP levels in patients with CTRCD. In addition, to date, no other multicentre studies had been published assessing the safety of sacubitril/valsartan in this special population.

The rapid development of effective oncologic therapies has improved cancer‐free and overall survivals, yet they can cause CTRCD with a known impact on cancer patient morbidity and mortality. Recently, Fornaro et al.3 reported that patients with CTRCD treated with optimized heart failure therapy have comparable overall survival rates with non‐ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy at 5 (86% and 88%, respectively) and 10 years (61% and 75%, respectively), despite cancer‐related morbidity and mortality.

However, presently, patients with cancer and cardiovascular disease do not always receive an optimal cardiovascular treatment; only half of them are treated with guideline‐based therapy or are referred to a cardiology consultation at the time of cancer diagnosis.8 Prioritization of cardio‐oncology teams is critical to ensure that patients receive the best cancer and cardiovascular therapy to improve their overall prognosis.9

Moreover, we showed a strong beneficial effect of sacubitril‐valsartan on reverse remodelling and LVEF. This finding is particularly noteworthy because it was obtained, although most of patients were not able to reach the full dose of the drug. Thus, after our initial observations, one could speculate that sacubitril significantly improve the management of CTRCD being necessary in all patients without specific contraindications.

On the other hand, tolerability of sacubitril‐valsartan in our population was good, and only four patients (6%) had to withdraw sacubitril–valsartan because of an adverse event. This percentage was lower than that observed in the PARADIGM population.6

Conclusions

Ours is the most comprehensive study reported so far presenting imaging, clinical, and laboratory data from field practice experience concerning to patients with CTRCD, before and after sacubitril–valsartan treatment. We evidenced improvements in echocardiographic functional and structural parameters, NT‐proBNP levels, and symptomatic status in this special oncologic population. Sacubitril–valsartan was also quite well tolerated in these patients. While more prospective data are required to confirm the beneficial role of sacubitril–valsartan in CTRD patients, our findings are promising and anticipate that sacubitril–valsartan may help to optimize CTRCD management, as in other HFrEF scenarios, according to current guidelines.4, 5

Conflict of interest

A.M‐.G. reports personal fees from Janssen, Novartis, and Daiichi Sankyo, outside the submitted work.

T.L‐.F. reports personal fees from Janssen, Gilead, Pfizer, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo, and TEVA, outside the submitted work.

C.M. has nothing to disclose.

M.C‐.M. has nothing to disclose.

P.M. reports personal fees and non‐financial support from Novartis and personal fees from Rovi, outside the submitted work

A.C.M‐.G. has nothing to disclose.

A.M‐.M. has nothing to disclose.

A.C. has nothing to disclose.

J.L.L‐.S. reports grants from Novartis, Pfizer, Boheringer Ingleheim, Sanofi, and Merk, outside the submitted work

P.L.S. has nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Spain, and the EU—European Regional Development Fund, by means of a competitive call for excellence in research projects (PIE14/00066) as well as by the Spanish Cardiovascular Network (CIBERCV).

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the patients who accepted to participate in the study.

Martín‐Garcia, A. , López‐Fernández, T. , Mitroi, C. , Chaparro‐Muñoz, M. , Moliner, P. , Martin‐Garcia, A. C. , Martinez‐Monzonis, A. , Castro, A. , Lopez‐Sendon, J. L. , and Sanchez, P. L. (2020) Effectiveness of sacubitril–valsartan in cancer patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 763–767. 10.1002/ehf2.12627.

Hospital Recruitment: Hospital Universitario La Paz (22); Hospital Universitario de Salamanca (21); Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Macarena (10); Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol (8); Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro (4); Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela (2).

References

- 1. Felker GM, Thompson RE, Hare JM, Hruban RH, Clemetson DE, Howard DL, Baughman KL, Kasper EK. Underlying causes and long‐term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1077–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tallaj JA, Franco V, Rayburn BK, Pinderski L, Benza RL, Pamboukian S, Foley B, Bourge RC. Response of doxorubicin‐induced cardiomyopathy to the current management strategy of heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005; 24: 2196–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fornaro A, Olivotto I, Rigacci L, Ciaccheri M, Tomberli B, Ferrantini C, Coppini R, Girolami F, Mazzarotto F, Chiostri M, Milli M, Marchionni N, Castelli G. Comparison of long‐term outcome in anthracycline‐related versus idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: a single centre experience. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, Gonzalez‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, E. S. C. S. D. Group . ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2129–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seferovic PM, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, de Boer RA, Drexel H, Gal TB, Hill L, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Anker MS, Lainscak M, Lewis BS, McDonagh T, Metra M, Milicic D, Mullens W, Piepoli MF, Rosano G, Ruschitzka F, Volterrani M, Voors AA, Filippatos G, Coats AJS. Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of The Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 1169–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Investigators P‐H. Committees, Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lopez‐Fernandez T, Martin Garcia A, Santaballa Beltran A, Montero Luis A, Garcia Sanz R, Mazon Ramos P, Velasco Del Castillo S, Lopez de Sa Areses E, Barreiro‐Perez M, Hinojar Baydes R, Perez de Isla L, Valbuena Lopez SC, Dalmau Gonzalez‐Gallarza R, Calvo‐Iglesias F, Gonzalez Ferrer JJ, Castro Fernandez A, Gonzalez‐Caballero E, Mitroi C, Arenas M, Virizuela Echaburu JA, Marco Vera P, Iniguez Romo A, Zamorano JL, Plana Gomez JC, Lopez Sendon Henchel JL. Cardio‐onco‐hematology in clinical practice. Position paper and recommendations. Revista espanola de cardiologia Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2017; 70: 474–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al‐Kindi SG, Oliveira GH. Prevalence of preexisting cardiovascular disease in patients with different types of cancer: the unmet need for onco‐cardiology. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91: 81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lancellotti P, Suter TM, Lopez‐Fernandez T, Galderisi M, Lyon AR, Van der Meer P, Cohen Solal A, Zamorano JL, Jerusalem G, Moonen M, Aboyans V, Bax JJ, Asteggiano R. Cardio‐oncology services: rationale, organization, and implementation. Eur Heart J 2019; 40: 1756–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]