Abstract

Right-sided colorectal cancer (RCRC) demonstrates worse survival outcome compared with left-sided CRC (LCRC). Recently, the importance of RNF43 mutation and BRAF V600E mutation has been reported in the serrated neoplasia pathway, which is one of the precancerous lesions in RCRC. It was hypothesized that the clinical significance of RNF43 mutation differs according to primary tumor sidedness. To test this hypothesis, the clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcome of patients with RNF43 mutation in RCRC and LCRC were investigated. Stage I–IV CRC patients (n=201) were analyzed. Genetic alterations including RNF43 using a 415-gene panel were investigated. Clinicopathological characteristics between RNF43 wild-type and RNF43 mutant-type were analyzed. Moreover, RNF43 mutant-type was classified according to primary tumor sidedness, i.e., right-sided RNF43 mutant-type or left-sided RNF43 mutant-type, and the clinicopathological characteristics between the two groups were compared. RNF43 mutational prevalence, spectrum and frequency between our cohort and TCGA samples were compared. RNF43 mutation was observed in 27 out of 201 patients (13%). Multivariate analysis revealed that age (≥65), absence of venous invasion, and BRAF V600E mutation were independently associated with RNF43 mutation. Among the 27 patients with RNF43 mutation, 12 patients were right-sided RNF43 mutant-type and 15 left-sided RNF43 mutant-type. Right-sided RNF43 mutant-type was significantly associated with histopathological grade 3, presence of lymphatic invasion, APC wild, BRAF V600E mutation, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), and RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutation compared with left-sided RNF43 mutant-type. Similarly, RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutations were more frequently observed in RCRC compared with LCRC in the TCGA cohort (P=0.042). Right-sided RNF43 mutant-type exhibited significantly worse overall survival than RNF43 wild-type and left-sided RNF43 mutant-type (P=0.001 and P=0.023, respectively) in stage IV disease. RNF43 mutation may be a distinct molecular subtype which is associated with aggressive tumor biology along with BRAF V600E mutation in RCRC.

Keywords: RNF43, primary tumor sidedness, BRAF V600E, next-generation sequencing, gene panel testing, colorectal cancer

Introduction

Primary tumor sidedness has prognostic and predictive value in metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC), and has thus emerged as a new biomarker (1,2). Several analyses revealed that right-sided colorectal cancer (RCRC) exhibited significantly worse prognosis than left-sided colorectal cancer (LCRC) (3–5), and anti-EGFR therapy clearly benefitted patients with LCRC, whereas patients with RCRC derived limited benefit (6–10). However, the mechanism of the differences between RCRC and LCRC has not been fully elucidated.

RCRC and LCRC have different clinicopathological and molecular characteristics. RCRC is generally characterized by being more common in women, and associated with Lynch syndrome, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P), mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), deficiency of mismatch repair genes, CpG island methylation, and KRAS and BRAF V600E mutations (11–15). LCRC is more common in men, and associated with familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, traditional serrated adenoma (TSA), chromosomal instability, ERBB1 and ERBB2 amplifications, and APC, p53, and NRAS mutations (11–15). Based on these clinicopathological and molecular differences, primary tumor sidedness is considered to be associated with prognosis and efficacy of targeted therapy.

Mutations in RNF43 have been reported in several solid tumors, such as colorectal (16–18), gastric (19), pancreatic (20), ovarian (21), and endometrial (22) cancers. RNF43 encodes a RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, and the protein is predicted to contain a transmembrane domain, a protease-associated domain, an ectodomain, and a cytoplasmic RING domain (23). Expression of RNF43 results in increased ubiquitination of frizzled receptors, and an alteration in their subcellular distribution, resulting in reduced surface levels of these receptors. RNF43 is considered to negatively regulate WNT signaling, and functions as a tumor suppressor. Loss of RNF43 results in decrease or lack of degradation of frizzled receptors, with an enhancement of WNT signaling. In cancer cells, inactivation of RNF43 through RNF43 mutation is one of the causes of permanent activation of the WNT signaling pathway (23).

Serrated neoplasia, which is a precancerous lesion of CRC, is associated with primary tumor sidedness: SSA/P is associated with RCRC, while TSA is associated with LCRC (24). Recently, several studies revealed the importance of RNF43 mutation in the serrated neoplasia pathway, i.e., RNF43 mutation was associated with serrated neoplasia pathway such as SSA/P (25) and TSA (26,27). Moreover, it has been reported that RNF43 mutation in serrated neoplasia is associated with BRAF V600E mutation (17), which is recognized as one of the characteristics of RCRC and a significant negative prognostic factor in metastatic CRC (1,2). Collectively, it was surmised that RNF43 mutation may play different roles in RCRC and LCRC. Recently, it has been reported that RNF43 mutations contribute to tumorigenesis in RCRC (18). However, to date, clinical significance of RNF43 mutation have not been fully investigated according to primary tumor sidedness. It was hypothesized that the clinical significance of RNF43 mutations differ between RCRC and LCRC. To test this hypothesis, the clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcome of patients with RNF43 mutation in RCRC and LCRC were investigated.

Materials and methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Niigata University School of Medicine, and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (G2015-0816). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and written informed consent was obtained from the patients. A total of 201 Japanese patients (117 male and 84 female patients; median age 65 years old; range, 30–94 years) with stage I–IV CRC according to AJCC, 7th edition (28) who underwent a primary tumor resection between January 2009 and December 2015 at the Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital or Niigata Cancer Center Hospital were included in this study. The median follow-up period was 34 months (range, 1–92 months). Patients diagnosed with adenocarcinoma were included. Patients under 18 years old were excluded. Patients with synchronous double primary CRC or other active concurrent malignant diseases, inflammatory bowel disease or familial adenomatous polyposis were excluded. No patient had received neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Typically, chemotherapy was administered according to the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines (29). Adjuvant chemotherapy, including fluorouracil or its derivatives ± oxaliplatin, was usually administered in stage III patients for six months. For patients with unresectable metastatic diseases, molecular targeted therapy was administered according to RAS mutational status.

In the present analysis, RNF43 mutational prevalence, spectrum and frequency between our cohort and TCGA samples were compared. The mutation information for the TCGA CRC-sequenced samples (n=489) was obtained from the cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/) (30) to assess mutation frequency.

Comprehensive genomic sequence analysis of primary tumors

As previously described (15,31–34), formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples were used for next-generation sequencing (NGS), and genetic alterations, including RNF43, were evaluated. Briefly, hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were used to assess tumor content, to ensure that >50% tumor content was present. Where applicable, unstained sections were macro-dissected to enrich for tumor content. DNA was extracted using a BioStic FFPE Tissue DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc.). All sample preparation, NGS, and bioinformatics analysis were performed in a CLIA/CAP-accredited laboratory (KEW, Inc.). DNA fragment libraries (50–150 ng) were prepared and enriched for the 415-gene panel with CANCERPLEX Version 3.0 (KEW, Inc.). An average 500X sequencing depth was achieved using Illumina MiSeq or NextSeq platforms. A proprietary bioinformatics platform and knowledge base were used to process genomic data and to identify multiple genomic abnormalities, including SNPs, small indels, copy number variation, and translocations. An allelic fraction threshold of 10% was used for SNPs and indels, and thresholds of >2.5-fold for gain, and 0.5-fold for loss, were used. Tumors were assessed for the presence of MSI on the basis of an extended loci panel. In addition to the Bethesda panel (35), a collection of 950 regions consisting of tandem repeats of one, two or three nucleotides with a minimum length of 10 bases was used (31). Tumor mutational burden was calculated as the number of non-synonymous mutations per megabase of sequence in the panel (panel size=1.3 Mb).

RNF43 status and clinicopathological characteristics

The 201 patients were classified into RNF43 wild-type or RNF43 mutant-type; moreover, RNF43 mutant-type were subdivided into right-sided RNF43 mutant-type or left-sided RNF43 mutant-type according to primary tumor sidedness. Primary tumor location was determined by operative findings. Cancer in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, or transverse colon was classified as RCRC; while cancer in the splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectosigmoid, or rectum was classified as LCRC (15).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM Japan, Inc.). Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate the associations between RNF43 status and clinicopathological characteristics. To clarify clinicopathological characteristics which were independently associated with RNF43 mutation, factors with a P-value of <0.10 in univariate analyses were entered into a multivariate analysis. Logistic analysis was performed to identify factors that were independently associated with RNF43 mutation. Five-year overall survival (OS) rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess for significant differences between subgroups. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Alteration of RNF43 in Japanese CRC

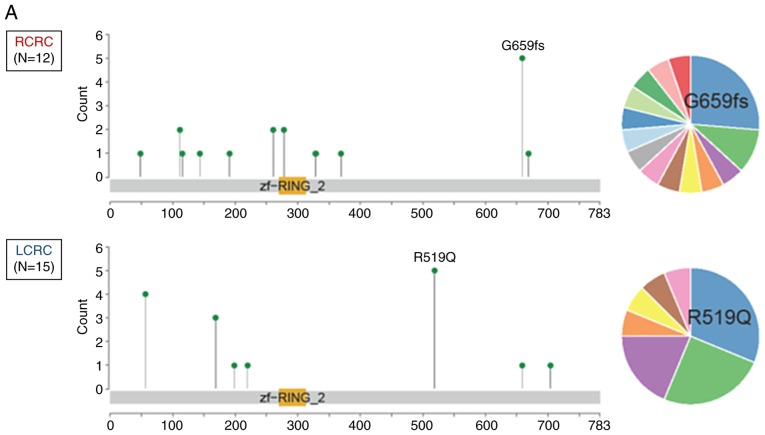

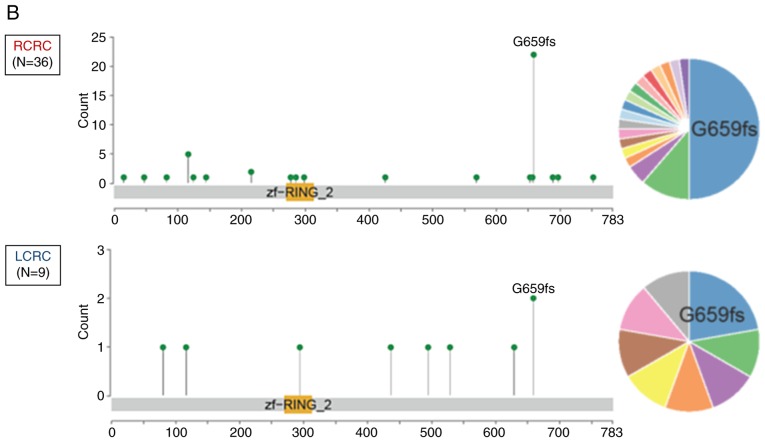

To date, there has been no studies regarding genetic alterations of RNF43 among Japanese CRC patients; hence, the genetic alterations of RNF43 were evaluated and compared with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data (https://www.cbioportal.org/). RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutation was more frequently observed in RCRC compared with LCRC in both of the Japanese cohorts (P<0.001; Figs. 1A and 2A) and TCGA samples (P=0.042; Figs. 1B and 2B).

Figure 1.

The location and frequency of RNF43 mutations according to primary tumor sidedness. (A) Japanese samples; (B) TCGA samples. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

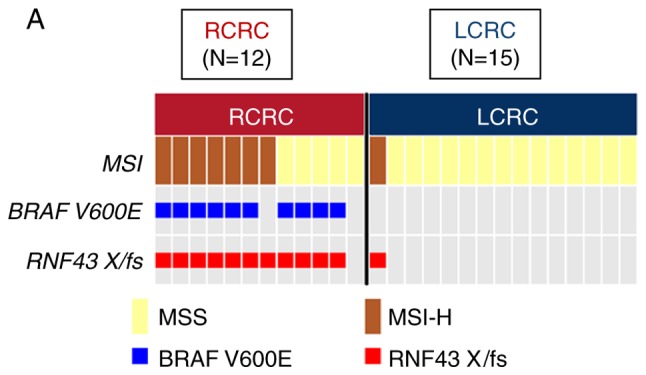

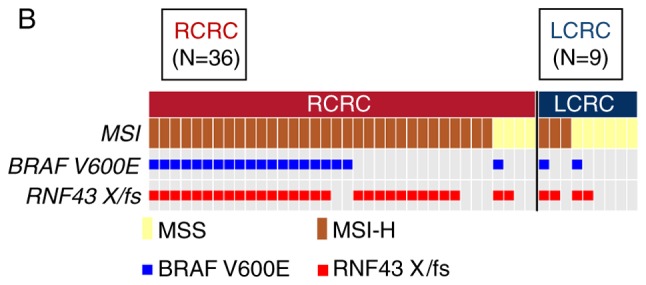

Figure 2.

Oncoprint of right-sided RNF43 mutant-type and left-sided RNF43 mutant-type. (A) Japanese samples; (B) TCGA samples. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

Clinicopathological characteristics in relation to RNF43 mutation status

The 415-gene panel assessment successfully detected genetic alterations in all 201 patients. The 415-gene panel assessment revealed that 174 (87%) patients were RNF43 wild-type and 27 (13%) patients were RNF43 mutant-type. RNF43 mutant-type was significantly associated with age (≥65; P=0.003), females (P=0.006), absence of venous invasion (P=0.003), absence of distant metastasis (P=0.021), BRAF V600E mutation (P<0.001), and MSI-H (P<0.001), and multivariate analysis revealed that age (≥65), absence of venous invasion, and BRAF V600E mutation were independently associated with RNF43 mutation (Table I).

Table I.

RNF43 gene status and other clinicopathological characteristics in colorectal cancer.

| RNF43 gene status | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Wild N (%) | Mutant N (%) | Univariate P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age (years) | |||||

| <65 | 94 (46) | 6 (3) | 0.003 | 1 | |

| ≥65 | 80 (40) | 21 (10) | 3.04 (1.03–8.90) | 0.042 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 108 (53) | 9 (4) | 0.006 | ||

| Female | 66 (33) | 18 (9) | |||

| Location | |||||

| Right side | 44 (22) | 12 (6) | 0.062 | ||

| Left side | 130 (65) | 15 (7) | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | |||||

| <50 | 75 (37) | 13 (6) | 0.679 | ||

| ≥50 | 99 (49) | 14 (7) | |||

| pT category | |||||

| T1, 2 | 20 (10) | 4 (2) | 0.539 | ||

| T3, 4 | 154 (76) | 23 (11) | |||

| Histopathological grading | |||||

| G1, 2 | 128 (63) | 19 (9) | 0.816 | ||

| G3 | 46 (23) | 8 (4) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | |||||

| Absence | 65 (32) | 14 (7) | 0.203 | ||

| Presence | 109 (54) | 13 (6) | |||

| Venous invasion | |||||

| Absence | 35 (17) | 13 (6) | 0.003 | 1 | |

| Presence | 139 (69) | 14 (7) | 0.18 (0.06–0.52) | 0.002 | |

| pN category | |||||

| N0 | 49 (24) | 10 (5) | 0.362 | ||

| N1, 2 | 125 (62) | 17 (8) | |||

| cM category | |||||

| M0 | 72 (36) | 18 (9) | 0.021 | ||

| M1 | 102 (51) | 9 (4) | |||

| APC | |||||

| Wild-type | 29 (14) | 9 (4) | 0.061 | ||

| Mutant | 145 (72) | 18 (9) | |||

| KRAS | |||||

| Wild-type | 105 (52) | 21 (10) | 0.091 | ||

| Mutant | 69 (34) | 6 (3) | |||

| BRAF V600E | |||||

| Wild-type | 171 (85) | 17 (9) | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Mutant | 3 (1) | 10 (5) | 45.68 (9.76–213.81) | <0.001 | |

| MSI | |||||

| MSI-H | 7 (3) | 8 (4) | <0.001 | ||

| MSS | 167 (84) | 19 (9) | |||

Fisher's exact test. CI, confidence interval; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high. Bold indicates P<0.05.

Genetic alterations of the MAPK pathway other than BRAF V600E mutation in RNF43 mutant-type

Seventeen of the 27 patients with RNF43 mutant-type had no BRAF V600E mutation. Nine of the 17 patients had mutations other than BRAF V600E in the MAPK pathway: 6 patients had KRAS mutation, 3 patients had BRAF non-V600E mutation; however, no patient had NRAS mutation.

RNF43 mutant-type according to primary tumor sidedness

Among the 27 patients with RNF43 mutation, 12 patients were right-sided RNF43 mutant-type and 15 left-sided RNF43 mutant-type. As revealed in Fig. 2A, 11 of the 12 right-sided RNF43 mutant-type had nonsense/frameshift mutations, while 14 of 15 left-sided RNF43 mutant-type had missense mutations. Right-sided RNF43 mutant-type was significantly associated with histopathological grade 3 (P=0.008), lymphatic invasion (P=0.021), APC wild (P=0.003), BRAF V600E mutation (P<0.001), MSI-H (P=0.008), and RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutation (P<0.001) compared with left-sided RNF43 mutant-type (Table II; Fig. 2A).

Table II.

Clinicopathological characteristics according to primary tumor sidedness in RNF43 mutant colorectal cancer.

| Primary tumor sidedness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Right-sided N (%) | Left-sided N (%) | P-value |

| Age (years) | |||

| <65 | 1 (4) | 5 (18) | 0.182 |

| ≥65 | 11 (40) | 10 (37) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3 (11) | 6 (22) | 0.683 |

| Female | 9 (33) | 9 (33) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | |||

| <50 | 5 (18) | 8 (29) | 0.704 |

| ≥50 | 7 (26) | 7 (26) | |

| pT category | |||

| T1, 2 | 1 (4) | 3 (11) | 0.605 |

| T3, 4 | 11 (40) | 12 (44) | |

| Histopathological grading | |||

| G1, 2 | 5 (18) | 14 (52) | 0.008 |

| G3 | 7 (26) | 1 (4) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | |||

| Absence | 3 (11) | 11 (40) | 0.021 |

| Presence | 9 (33) | 4 (15) | |

| Venous invasion | |||

| Absence | 4 (15) | 9 (33) | 0.252 |

| Presence | 8 (30) | 6 (22) | |

| pN category | |||

| N0 | 3 (11) | 7 (26) | 0.424 |

| N1, 2 | 9 (33) | 8 (30) | |

| cM category | |||

| M0 | 8 (30) | 10 (37) | 0.999 |

| M1 | 4 (15) | 5 (18) | |

| APC | |||

| Wild-type | 8 (30) | 1 (4) | 0.003 |

| Mutant | 4 (15) | 14 (52) | |

| KRAS | |||

| Wild-type | 11 (40) | 10 (37) | 0.182 |

| Mutant | 1 (4) | 5 (18) | |

| BRAF V600E | |||

| Wild-type | 2 (7) | 15 (55) | <0.001 |

| Mutant | 10 (37) | 0 (0) | |

| MSI | |||

| MSI-H | 7 (26) | 1 (4) | 0.008 |

| MSS | 5 (18) | 14 (52) | |

| Variants of RNF43 | |||

| Nonsense or frameshift | 11 (40) | 1 (4) | <0.001 |

| Missense | 1 (4) | 14 (52) | |

Fisher's exact test. MSI, microsatellite instability; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high. Bold indicates P<0.05.

Overall survival in relation to RNF43 status and primary tumor sidedness

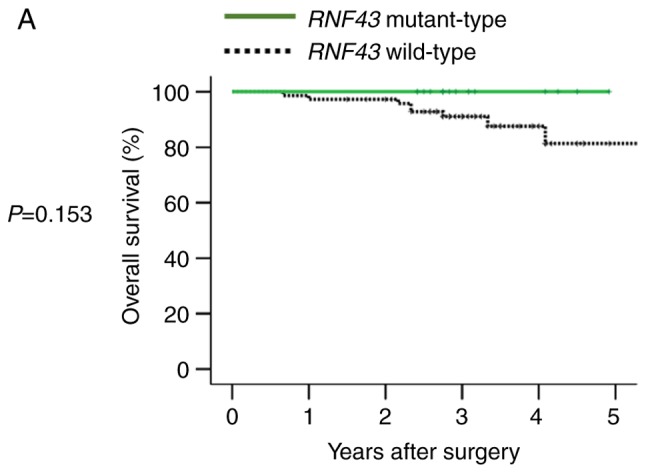

In 90 patients with stage I–III disease, RNF43 mutation was not a significant prognostic factor for 5 year OS (Fig. 3A), and primary tumor sidedness was not associated with RNF43 mutant-type.

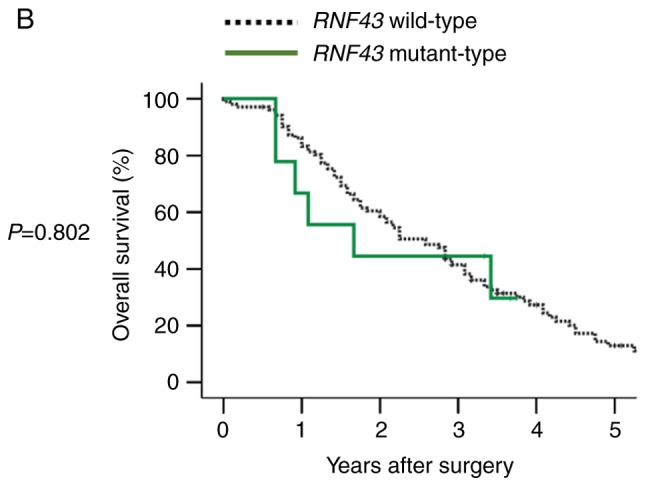

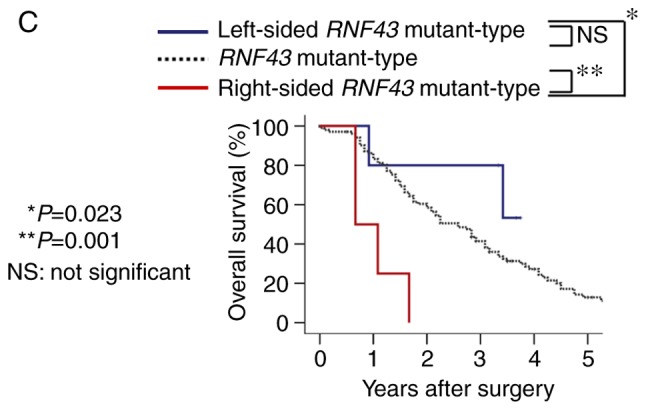

Figure 3.

Overall survival according to RNF43 mutation status and primary tumor sidedness. (A) Overall survival of RNF43 wild-type and RNF43 mutant-type in stage I–III colorectal cancer. (B) Overall survival of RNF43 wild-type and RNF43 mutant-type in stage IV colorectal cancer. (C) Overall survival of RNF43 wild-type, right-sided RNF43 mutant-type, and left-sided RNF43 mutant-type in stage IV colorectal cancer.

In 111 patients with stage IV disease, RNF43 mutation was not a significant prognostic factor for OS (Fig. 3B). However, when RNF43 mutant-type was subdivided into right-sided RNF43 mutant-type or left-sided RNF43 mutant-type according to primary tumor sidedness, right-sided RNF43 mutant-type exhibited significantly worse overall survival than RNF43 wild-type and left-sided RNF43 mutant-type (P=0.001 and P=0.023, respectively; Fig. 3C). Regarding variants of RNF43 mutations, all right-sided RNF43 mutant-type had nonsense mutation (R145X) or frameshift mutation (P192fs, S262fs, G659fs), while all left-sided RNF43 mutant-type had missense mutations (T58S, W200C, R221W, R519Q; Table III). All the four right-sided RNF43 mutant-type were older in age (≥65), females, and BRAF V600E mutant-type. Three of four patients with right-sided RNF43 mutation had two or more metastatic sites; conversely, all five patients with left-sided RNF43 mutation had one metastatic site. While all patients with right-sided RNF43 mutant-type succumbed to their cancer, three of the five patients with left-sided RNF43 mutant-type were alive at the final follow-up (Table III).

Table III.

Clinical course of RNF43 mutant-type patients with Stage IV disease.

| Genetic alteration | Age | Sex | Primary tumor location | KRAS status | BRAF status | MSI status | Tumor mutational burden | Initial metastatic sites | Treatment | Survival status (months after primary tumor resection) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S262fs | 71 | F | Right | Wild | V600E | MSS | 19 | Liver, Lung, Spleen, Peritoneum | R2 resection (Primary) → FOLFOX + Bmab → FOLFIRI | Dead (8 months) |

| R145X | 66 | F | Right | Wild | 26_34del, V600E | MSS | 19 | Para-aortic lymph node | R0 resection (Primary and Para-aortic LN) → Lung, LN recurrence → FOLFOX + Bmab | Dead (13 months) |

| P192fs | 80 | F | Right | Wild | V600E | MSS | 18 | Lung | R2 resection (Primary) → XELOX + Bmab | Dead (20 months) |

| G659fs | 78 | F | Right | Wild | V600E | MSI-H | 48 | Liver, Peritoneum | R2 resection (Primary) → FOLFOX + Pmab | Dead (8 months) |

| R519Q | 35 | F | Left | Wild | Wild | MSS | 10 | Liver | R2 resection (Primary) → FOLFOX + Bmab → R0 resection (Liver) → Liver and lung recurrence → FOLFOX + Bmab → FOLFIRI + Pmab | Alive (44 months) |

| R519Q | 86 | M | Left | Wild | Wild | MSS | 11 | Lung | R2 resection (Primary) → Xeloda → XELOX + Bmab → IRIS + Pmab | Alive (45 months) |

| W200C | 70 | F | Left | Wild | D594G | MSS | 19 | Liver | R2 resection (Primary) → R0 resection (Liver) → Liver recurrence → R0 resection (Liver) | Alive (40 months) |

| R221W | 77 | M | Left | Wild | Wild | MSS | 12 | Liver | R2 resection (Primary) → XELOX → IRIS → Pmab | Dead (11 months) |

| T58S | 75 | F | Left | Wild | Wild | MSS | 11 | Liver | R2 resection (Primary) → XELOX + Bmab → R0 resection (Liver) → Lung recurrence | Dead (41 months) |

FOLFOX = 5FU + Leucovorin + Oxaliplatin; FOLFIRI = 5FU + Leucovorin + Irinotecan; XELOX = Xeloda + Oxaliplatin; IRIS = Irinotecan + S-1. Bmab, Bevacizumab; Pmab, Panitumumab; MSS, microsatellite stable.

Discussion

This analysis has three main findings regarding RNF43 mutations in CRC. Firstly, most of RNF43 mutations in RCRC were nonsense or frameshift mutations, while those in LCRC were missense mutations. Secondly, right-sided RNF43 mutant-type was significantly associated with histopathological grade 3 and BRAF V600E mutation. Thirdly, right-sided RNF43 mutant-type exhibited significantly worse OS than left-sided RNF43 mutant-type. These results indicated that right-sided RNF43 mutant-type is one of the clinically important subtypes in CRC, and RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutations, along with BRAF V600E mutation, may be a possible cause of worse prognosis of RCRC.

In this analysis, it was revealed that 13% of the Japanese CRC patients in this study had RNF43 mutations, while 9% of patients in the TCGA cohort had RNF43 mutations (36,37). Recently, several studies have revealed the role of RNF43 mutations in the serrated neoplastic pathway of CRC. Hashimoto et al reported that WNT pathway gene mutations, including RNF43 mutation, were more common in SSA/P with dysplasia than in SSA/P without dysplasia, and suggested that WNT pathway gene mutations are involved in the development of dysplasia in SSA/P (25). Tsai et al reported the incidence of RNF43 mutation in SSA/P (10%) and TSA (28%), and stated that RNF43 mutation is an early and specific molecular aberration in the serrated neoplasia pathway (26). Yan et al reported RNF43 germline and somatic mutation along with BRAF V600E mutation in the serrated neoplasia pathway (16). However, the clinical significance of RNF43 mutation has not been fully elucidated; hence, the clinicopathological characteristics of RNF43 mutation were investigated, with a focus on the association between RNF43 mutation and primary tumor sidedness.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which investigated the survival outcome of RNF43 mutant-type according to primary tumor sidedness in CRC. Previous studies have reported that hotspot mutations, mainly frameshift (R117fs and G659fs), are found in microsatellite-instable SSA/P and CRC (23). In this analysis, 201 patients with stage I–IV CRC were investigated, and it was revealed that 11 out of 12 right-sided RNF43 mutant-type had nonsense/frameshift mutations, while 14 out of 15 left-sided RNF43 mutant-type had missense mutations. Although RNF43 protein expression was not investigated, RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutation may be a cause of loss of function of RNF43 protein. It is speculated that RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutation can become a cause of stimulation of the WNT signaling pathway, and is associated with the aggressive tumor biology of RCRC.

Approximately 5 to 9% patients with CRC have BRAF V600E mutation, and BRAF V600E mutation is recognized as a distinct molecular subtype of CRC (1,2). Multiple studies have revealed that the BRAF V600E mutation is associated with poor prognosis in metastatic CRC (38,39), as well as poor response to anti-EGFR therapy in later lines of therapy (40,41). In the present study, it was revealed that 10 out of 12 right-sided RNF43 mutant-type had BRAF V600E mutation. It is surmised that both RNF43 and BRAF V600E mutations are important for the tumor biology of right-sided RNF43 mutant-type; i.e., RNF43 nonsense/frameshift mutation, along with BRAF V600E mutation, induce enhancement of both the WNT and MAPK signaling pathways, resulting in a worse prognosis in right-sided RNF43 mutant-type.

In stage IV disease, it was revealed that right-sided RNF43 mutant-type exhibited significantly worse OS than left-sided RNF43 mutant-type, and all patients with right-sided RNF43 mutant-type succumbed to their cancer. These results suggest that right-sided RNF43 mutant-type is a distinct subtype that has potentially worse prognosis. We consider that RNF43 mutation should be treated differently according to primary tumor sidedness, since the clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes differ between right-sided RNF43 mutant-type and left-side RNF43 mutant-type. Thus, how should this dismal molecular subtype ‘right-sided RNF43 mutant-type’ be treated? At present, right-sided RNF43 mutant-type may be treated the same as BRAF V600E mutant-type (1,2), since it was revealed that most right-sided RNF43 mutant-type cases had BRAF V600E mutation in this analysis. In the future, WNT signaling plus BRAF inhibitors may be applied for right-sided RNF43 mutant-type (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02278133).

This analysis has some limitations. First, this retrospective analysis was performed at two institutions. Second, it included a small number of patients; specifically, the study had only 90 patients with Stage I–III disease. Future analysis should include a larger number of patients with CRC from large-scale multi-institutional studies or a cancer registry. It is speculated that the microbiome may be associated with tumor carcinogenesis and phenotype, and certain bacteria may be associated with genetic alterations in CRC. For example, it has been reported that Fusobacterium nucleatum is enriched in tumor tissue of MSI-H CRC (42,43). Although we do not have data linking the microbiome to the results of our study at present, we plan to investigate the relationship between genetic alteration of right-sided CRC and the patient microbiome. Collectively, this analysis is important for clarifying the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of RNF43 mutant-type according to primary tumor sidedness, and facilitating the research of future treatment strategies.

In conclusion, clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcome of patients with RNF43 mutation may differ between RCRC and LCRC. In RCRC, RNF43 mutation may be a small, but distinct molecular subtype that is associated with aggressive tumor biology along with BRAF V600E mutation. Future preclinical and clinical studies may have to focus on RNF43 mutation to improve survival outcome in CRC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Denka Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan and, in part, by JSPS KAKENHI grant nos. JP18K08612 and JP17K10624.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YS and AM provided substantial contributions to the design and interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. MaeN, HO, YoT, MasN, HK, YH, HI, MNag, HN, SM, YaT, and TW provided substantial contributions to the acquisition of clinical data and interpretation of data. YL and SO provided substantial contributions to the statistical analysis of the data and creation of the figures. TW critically revised the work and provided final approval of article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Niigata University School of Medicine, and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (G2015-0816). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network, corp-author. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology-colon cancer (version 2, 2019) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf

- 2.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, Aranda Aguilar E, Bardelli A, Benson A, Bodoky G, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386–1422. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loupakis F, Yang D, Yau L, Feng S, Cremolini C, Zhang W, Maus MK, Antoniotti C, Langer C, Scherer SJ, et al. Primary tumor location as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:dju427. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O'Connor ES, King J, LoConte N, Kennedy G, Smith MA. Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: Analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-Medicare data. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4401–4409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishihara S, Murono K, Sasaki K, Yasuda K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Kawai K, Hata K, et al. Impact of primary tumor location on postoperative recurrence and subsequent prognosis in nonmetastatic colon cancers: A multicenter retrospective study using a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2018;267:917–921. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, Modest DP, Heinemann V. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Borgonovo K, Ghidini M, Turati L, Dallera P, Passalacqua R, Sgroi G, Barni S. Prognostic survival associated with left-sided vs. right-sided colon cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:211–219. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, Tabernero J, Van Cutsem E, Beier F, Esser R, Lenz HJ, Heinemann V. Prognostic and predictive relevance of primary tumor location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: Retrospective analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:194–201. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, Peeters M, Lenz HJ, Venook A, Heinemann V, Van Cutsem E, Pignon JP, Tabernero J, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1713–1729. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeckx N, Koukakis R, Op de Beeck K, Rolfo C, Van Camp G, Siena S, Tabernero J, Douillard JY, André T, Peeters M. Primary tumor sidedness has an impact on prognosis and treatment outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from two randomized first-line panitumumab studies. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1862–1868. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breivik J, Lothe RA, Meling GI, Rognum TO, Børresen-Dale AL, Gaudernack G. Different genetic pathways to proximal and distal colorectal cancer influenced by sex-related factors. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:664–669. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971219)74:6<664::AID-IJC18>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iacopetta B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int J Cancer. 2002;101:403–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, Magill L, Beaumont C, Stahlschmidt J, Richman S, Chambers P, Seymour M, Kerr D, et al. Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1261–1270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen H, Yang J, Huang Q, Jiang MJ, Tan YN, Fu JF, Zhu LZ, Fang XF, Yuan Y. Different treatment strategies and molecular features between right-sided and left-sided colon cancers. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6470–6478. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimada Y, Kameyama H, Nagahashi M, Ichikawa H, Muneoka Y, Yagi R, Tajima Y, Okamura T, Nakano M, Sakata J, et al. Comprehensive genomic sequencing detects important genetic differences between right-sided and left-sided colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:93567–93579. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan HHN, Lai JCW, Ho SL, Leung WK, Law WL, Lee JFY, Chan AKW, Tsui WY, Chan ASY, Lee BCH, et al. RNF43 germline and somatic mutation in serrated neoplasia pathway and its association with BRAF mutation. Gut. 2017;66:1645–1656. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eto T, Miyake K, Nosho K, Ohmuraya M, Imamura Y, Arima K, Kanno S, Fu L, Kiyozumi Y, Izumi D, et al. Impact of loss-of-function mutations at the RNF43 locus on colorectal cancer development and progression. J Pathol. 2018;245:445–455. doi: 10.1002/path.5098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai C, Sun W, Wang X, Xu X, Li M, Huang D, Xu E, Lai M, Zhang H. RNF43 frameshift mutations contribute to tumourigenesis in right-sided colon cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215:152453. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang K, Yuen ST, Xu J, Lee SP, Yan HH, Shi ST, Siu HC, Deng S, Chu KM, Law S, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and comprehensive molecular profiling identify new driver mutations in gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2014;46:573–582. doi: 10.1038/ng.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang X, Hao HX, Growney JD, Woolfenden S, Bottiglio C, Ng N, Lu B, Hsieh MH, Bagdasarian L, Meyer R, et al. Inactivating mutations of RNF43 confer Wnt dependency in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12649–12654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryland GL, Hunter SM, Doyle MA, Rowley SM, Christie M, Allan PE, Bowtell DD, Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Gorringe KL, Campbell IG. RNF43 is a tumour suppressor gene mutated in mucinous tumours of the ovary. J Pathol. 2013;229:469–476. doi: 10.1002/path.4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giannakis M, Hodis E, Jasmine Mu X, Yamauchi M, Rosenbluh J, Cibulskis K, Saksena G, Lawrence MS, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, et al. RNF43 is frequently mutated in colorectal and endometrial cancers. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1264–1266. doi: 10.1038/ng.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serra S, Chetty R. Rnf43. J Clin Pathol. 2018;71:1–6. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. 4th. IARC; Lyon: 2010. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto T, Yamashita S, Yoshida H, Taniguchi H, Ushijima T, Yamada T, Saito Y, Ochiai A, Sekine S, Hiraoka N. WNT pathway gene mutations are associated with the presence of dysplasia in colorectal sessile serrated adenoma/polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1188–1197. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai JH, Liau JY, Yuan CT, Lin YL, Tseng LH, Cheng ML, Jeng YM. RNF43 is an early and specific mutated gene in the serrated pathway, with increased frequency in traditional serrated adenoma and its associated malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1352–1359. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekine S, Yamashita S, Tanabe T, Hashimoto T, Yoshida H, Taniguchi H, Kojima M, Shinmura K, Saito Y, Hiraoka N, et al. Frequent PTPRK-RSPO3 fusions and RNF43 mutations in colorectal traditional serrated adenoma. J Pathol. 2016;239:133–138. doi: 10.1002/path.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. 7th. Springer; New York: 2010. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe T, Muro K, Ajioka Y, Hashiguchi Y, Ito Y, Saito Y, Hamaguchi T, Ishida H, Ishiguro M, Ishihara S, et al. Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2016 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:1–34. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagahashi M, Wakai T, Shimada Y, Ichikawa H, Kameyama H, Kobayashi T, Sakata J, Yagi R, Sato N, Kitagawa Y, et al. Genomic landscape of colorectal cancer in Japan: Clinical implications of comprehensive genomic sequencing for precision medicine. Genome Med. 2016;8:136. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimada Y, Yagi R, Kameyama H, Nagahashi M, Ichikawa H, Tajima Y, Okamura T, Nakano M, Nakano M, Sato Y, et al. Utility of comprehensive genomic sequencing for detecting HER2-positive colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2017;66:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimada Y, Tajima Y, Nagahashi M, Ichikawa H, Oyanagi H, Okuda S, Takabe K, Wakai T. Clinical significance of BRAF Non-V600E mutations in colorectal cancer: A retrospective study of two institutions. J Surg Res. 2018;232:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oyanagi H, Shimada Y, Nagahashi M, Ichikawa H, Tajima Y, Abe K, Nakano M, Kameyama H, Takii Y, Kawasaki T, et al. SMAD4 alteration associates with invasive-front pathological markers and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2019;74:873–882. doi: 10.1111/his.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, Sidransky D, Eshleman JR, Burt RW, Meltzer SJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Fodde R, Ranzani GN, Srivastava S. A national cancer institute workshop on microsatellite instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: Development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cancer Genome Atlas Network, corp-author. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. TCGA, PanCancer data. https://www.cell.com/pb-assets/consortium/pancanceratlas/pancani3/index.html

- 38.Tol J, Nagtegaal ID, Punt CJ. BRAF mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:98–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1023–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peeters M, Oliner KS, Parker A, Siena S, Van Cutsem E, Huang J, Humblet Y, Van Laethem JL, André T, Wiezorek J, et al. Massively parallel tumor multigene sequencing to evaluate response to panitumumab in a randomized phase III study of metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1902–1912. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seymour MT, Brown SR, Middleton G, Maughan T, Richman S, Gwyther S, Lowe C, Seligmann JF, Wadsley J, Maisey N, et al. Panitumumab and irinotecan versus irinotecan alone for patients with KRAS wild-type, fluorouracil-resistant advanced colorectal cancer (PICCOLO): A prospectively stratified randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:749–759. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee DW, Han SW, Kang JK, Bae JM, Kim HP, Won JK, Jeong SY, Park KJ, Kang GH, Kim TY. Association between fusobacterium nucleatum, pathway mutation, and patient prognosis in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3389–3395. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamada T, Zhang X, Mima K, Bullman S, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Kosumi K, Masugi Y, Twombly TS, Cao Y, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer relates to immune response differentially by tumor microsatellite instability status. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:1327–1336. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.