Abstract

Background

Poor ovarian response (POR) is one reason for infertility. In vitro fertilization (IVF) is frequently used to help achieve pregnancy, and performing acupuncture before IVF may promote ovulation and reduce egg retrieval pain. The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture on clinical pregnancy rates (CPR) after IVF in women with POR.

Methods

Eight electronic databases were searched in January 2020, and reference lists of retrieved articles and previous review articles were hand-searched. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using any type of acupuncture for women with POR undergoing IVF were considered. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias standards.

Results

Three RCTs were included in this review. CPR and the number of retrieved oocytes were measured in two studies, while the values of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and antral follicle count (AFC) were only reported in one study. In two studies, CPR was higher in the intervention group than the control group [37.8 % vs 24.3 %]. We did not conduct a meta-analysis, as there was a high level of heterogeneity in interventions among the included trials.

Conclusions

This study suggests that acupuncture may improve CPR, AMH, AFC and the number of retrieved oocytes in women with POR undergoing IVF. However it is difficult to conclude that acupuncture is more effective than conventional treatment. Additionally, more clinical trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture on CPR and other outcomes of POR.

Study registration

PROSPERO CRD42018087813; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018087813

Keywords: Infertility, Poor ovarian response, Diminished ovarian reserve, In vitro fertilization, Acupuncture

1. Introduction

Infertility is defined as a couple’s inability to conceive after one year of regular and unprotected sex.1 Approximately 15% of couples worldwide are affected by infertility, and 1.5 million married women aged 15–44 years reported infertility from 2006 to 2010 in the United States.2 Infertility is caused by various factors including age, underlying diseases, environmental toxins, genetic conditions, and general lifestyle. In vitro fertilization (IVF) is a frequently used treatment method to achieve pregnancy.3 The success rate of IVF increases in conditions with good response to controlled ovarian stimulation (COS).4

Poor ovarian response (POR) has been accepted as a predictor of delivery in women over 40 undergoing IVF.5 At least two of the following three conditions are required to diagnose POR: 1) advanced maternal age (≥40 years) or any other risk factor for POR; 2) a previous POR (≤3 oocytes after a conventional stimulation protocol); or 3) an abnormal ovarian reserve test (i.e., antral follicle count (AFC) <5-7 follicles or anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) <0.5-1.1 ng/ml).6 AMH is used as a predictor for ovarian reserve, and a higher level of AMH tends to increase during natural pregnancy.7 Low AFC is the basis for diagnosing POR, and AFC testing is more accurate than basal follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) testing for women aged over 44 years in predicting IVF outcome.8

Acupuncture has been used to treat infertility, as it improves the endometrium, promotes ovulation, and reduces pain during egg retrieval. Additionally, acupuncture is utilized in combination with IVF to improve fertilization rates.9 Based on previous studies by Ho et al.10 and Stener-Victorin et al.,11 electroacupuncture can reduce uterine artery blood flow impedance in infertile women undergoing IVF. Since ovarian stromal blood flow has been frequently used to predict ovarian response prior to IVF, acupuncture may affect ovarian response.12

There are several systematic reviews13, 14, 15 of the effectiveness of acupuncture in raising pregnancy rates in women undergoing IVF. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture in improving clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) after IVF, in women with POR from randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

2. Methods

2.1. Study registration

The protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42018087813).

2.2. Search method for identifying the studies

2.2.1. Search databases

This study included eight electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, three Korean databases (OASIS, KoreaMed, and KMBASE), and one Chinese database (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, CNKI). The reference lists of the retrieved articles were hand-searched, and previous review articles were also examined.

2.2.2. Search strategy

Acupuncture and in vitro fertilization were selected as the basic search terms of this study. The key words used for searching were ‘in vitro fertilization’, ‘infertility’, and ‘acupuncture’, in English, Chinese, and Korean. Language and publication dates were not restricted. Data were searched on Jan 10, 2020.

2.3. Inclusion criteria of this review

2.3.1. Types of studies

This systematic review included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that were peer-reviewed. Other designs such as observational, cohort, case reports, case series, non-RCT, and animal and experimental studies were excluded, as were theses.

2.3.2. Types of participants

Participants were women with POR receiving IVF for treatment of infertility. There were no restrictions in POR diagnosis criteria or participant age. IVF with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) was allowed. Patients with serious diseases were excluded.

2.3.3. Types of interventions

All types of acupuncture (i.e., manual acupuncture, ear acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, or warm acupuncture) were included in this review. We planned to compare trials using the same type of acupuncture in a meta-analysis. Acupressure, which does not penetrate skin, was excluded. RCTs were also excluded if they were used in combination with other interventions such as herbal medicines, moxibustion, or Western therapies. Cases in which other interventions (e.g., IVF, drugs, and diets) were used identically in all groups were included.

2.3.4. Types of comparisons

There was no special restriction on comparisons. Sham acupuncture, active-control (including Western medicines and dietary supplements), no-treatment, and wait-list controlled were considered control groups. RCTs that compared the effectiveness of acupuncture on acupoints were excluded.

2.3.5. Type of outcome measures

The primary outcome was clinical pregnancy rate (CPR). Secondary outcomes were anti-mullerian hormone (AMH), antral follicle count (AFC), number of retrieved oocytes, and live birth rate (LBR). RCTs that assessed one or more outcome measures were included in this review.

2.4. Data collection, extraction and assessment

2.4.1. Selection of studies

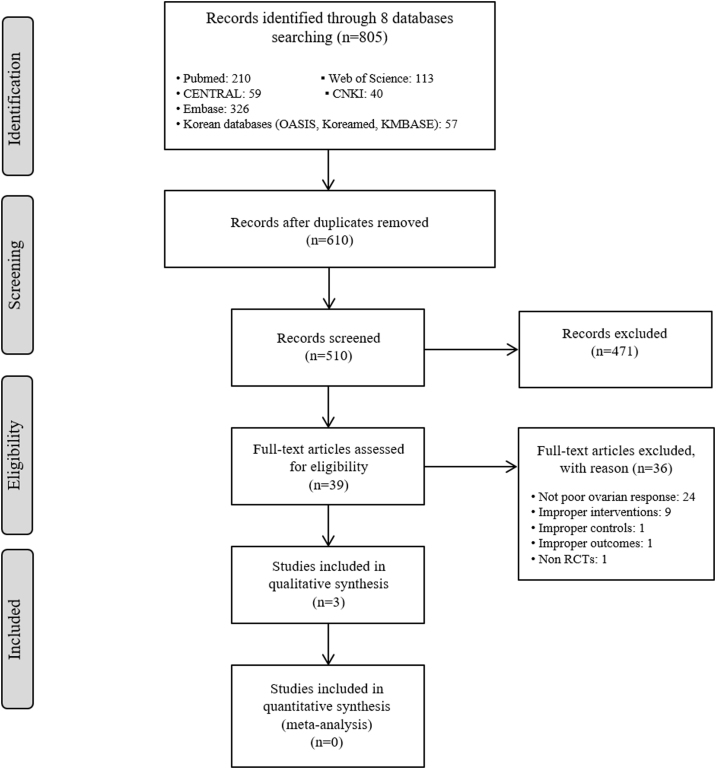

Two authors (SJ and SY) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the searched studies after excluding any duplication of literature articles from the eight databases. Then, the full text of the selected articles was reviewed to ensure that each article met the inclusion criteria for this review. Literature written in Chinese was reviewed with the help of a reviewer (JHJ) fluent in Chinese. Another reviewer (KHK) was involved and made a decision when two authors showed a difference of opinion. The entire process is summarized in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)16 flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection.

2.4.2. Data extraction

One author (SJ) extracted data, and another author (SSY) reviewed the extracted document. Basic characteristics such as participant, intervention, comparison, outcome, and adverse events of each included study were retrieved. Detailed information on acupuncture was extracted using the standards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (STRICTA) reporting guideline.17

2.4.3. Assessment of risk of bias

Two reviewers (SJ and SSY) assessed the quality of included studies using the Risk of Bias (RoB) tool developed by Cochrane. RoB consists of the following seven items: 1) random sequence generation; 2) allocation concealment; 3) blinding of participants and personnel; 4) blinding of outcome assessment; 5) completeness of outcome data; 6) completeness of reporting; and 7) other sources of bias. Each item of every RCT was categorized as “high risk (H)”, “unclear (U)”, or “low risk (L)”. The RoB graph was drawn by Review Manager (Cochrane Collaboration Software, RevMan) version 5.3.

3. Results

3.1. Description of included trials

From the eight searched databases we identified 805 records. Among these, 610 articles remained after eliminating duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 49 articles remained, and 3 RCTs were included in this review after reviewing full texts. The flow chart of study selection and exclusion reasoning is shown in Fig. 1. All three clinical studies18, 19, 20 were conducted in China. Two18, 20 of these were written in Chinese, and one19 was written in English. Two RCTs19, 20 were four-arm clinical trials. The treatment period of each trial was one or three cycles of ovulation. The numbers of participants for the trials were 60,18 100,20 and 240.19 All trials targeted women with POR or diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) undergoing IVF-embryo transfer. The mean age of participant ranged from 33 to 36 years old. One RCT18 also included participants with kidney deficiency, which is one of the inclusion criteria in the Chinese pattern identification for POR. Two trials19, 20 used age, history of surgery, AFC, or FSH levels as inclusion criteria.

The main intervention used in two studies was electroacupuncture treatment administered once a day. In the study by Chen et al.,18a superovulation intervention was also provided with electroacupuncture and was used in both the intervention and control groups. A superovulation program consists of intramuscular injection of recombinant follicle stimulating hormone. Due to intervention heterogeneity between studies, we did not conduct a meta-analysis in this review. In the study by Dong et al.,20 the intervention used was general acupuncture and Climen (a composition of estradiol valerate and cyproterone acetate) treatment, combined with a microstimulation ovulation program. Table 2 describes the details of acupuncture treatment.

Table 2.

Detailed information of acupuncture treatments: following STRICTA.

| Item | Detail | Study |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen 2009 | Zheng 2015 | Dong 2019 | ||

| Acupuncture rationale | Style of acupuncture | Traditional Chinese medicine | Traditional Chinese medicine | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| Reasoning for treatment provided | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | |

| Extent to which treatment was varied | No variation | No variation | Not reported | |

| Details of needling | Number of needle insertions per subject per session | 7 acupoints | 8 acupoints | 4 acupoints |

| Names of points used | CV4, KI3, SP6, EX-CA1, CV3, LR3 | CV4, CV3, SP6, EX-CA1, ST25, BL23, GV3, GV4 | CV4, KI3, SP6, LR3 | |

| Depth of insertion | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | |

| Response sought | Frequency of 16–18 times/min, dense wave | Frequency of 2 Hz, strength of 20–25 mA | Until there is a sense of tightness under the needle | |

| Needle stimulation | Electroacupuncture | Electroacupuncture | CV4: twisting method | |

| Needle retention time | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | |

| Needle type | G6805-1 | · Needle: Han’s acupoint nerve stimulator (HANS) developed by the Neurological Institute of Peking University (Beijing, China) · Electrode patch: Han’s device (Medical Technology Co., Ltd. Nanjing Jisheng) |

Needle: 25 mm x 40 mm, Suzhou Dongbang Medical Equipment Co., Ltd. | |

| Treatment regimen | Number of treatment sessions Frequency and duration of treatment sessions |

Once daily, from 2 days after the end of menstrual cycle until ovulation | Once daily, for 3 menstrual cycles | Once daily from 8-15th day of menstruation, for 3 cycles |

| Other components of treatment | Details of other interventions administered to the acupuncture group | Superovulation programme | No other interventions except IVF-ET | 1) Microstimulation ovulation program 2) Climen |

| Setting and context of treatment | Same with control | Not reported | 1) Oral administration of Clomiphene, muscular injection of Menotrophin Chorionic Gonadotrophin triggering, etc. 2) Tablet composed of estradiol valerate and cyproterone acetate |

|

| Practitioner background | Description of participating acupuncturists | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Control or comparator interventions | Rationale for the comparator | Existing treatment | Existing treatment | Existing treatment |

| Precise description of the control or comparator | Superovulation programme - Intramuscular injection of recombinant FSH on the 3rd day of menstrual cycle hormone (Gonal-F, 75 U/branch, Serono, Switzerland) 300 U/d, 8th days of menstrual cycle - Subcutaneous injection of cetrorelix acetate (Cetrorelix, German Baxter Oncology GmbH), 0.25 mg, once daily |

1) Sham electroacupuncture −5 mA; the electric current was tuned on for 3 s and paused for 7s 2) Artificial endometrial cycle treatment - Progynova (2 mg/day for 21 days, from 5th day of menstruation - Duphaston (20 mg/day, ten days prior to the last administration of Progynova) 3) IVF-ET with no other treatment |

1) Acupuncture + Microstimulation ovulation program 2) Climen + Microstimulation ovulation prog`ram 3) Microstimulation ovulation program |

|

FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer; n.r., not reported.

There were three types of comparisons in all three included trials. Active-control, placebo, and no-treatment were considered control groups. Progynova and Duphaston treatment, which are conventional medicines for infertility, were used as the active-controls. The study by Zheng et al.19 was a four-arm trial, and therefore artificial endometrial cycle treatment, sham electro-acupuncture, and no treatment were all applied to each of the three control groups. Sham electroacupuncture uses a scientific instrument similar to actual electroacupuncture. The electric current was 5 mA, which was used for 3 s and paused for 7 s. Consequently, patients could be blinded and felt sensation and numbness in the acupoints. A superovulation programme was applied to the control group in the Chen et al. study.18 In the Dong et al. study,20 a microstimulation ovulation program was used in all four groups, and acupuncture alone, Climen alone, and no other treatment were used in three control groups, respectively. The details are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included randomized controlled trials.

| First author (year) [Ref] Country |

Sample size [enrolled] | Age [mean] |

Inclusion criteria | Treatment period | Intervention | Control | Outcomes | Results | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen (2009)18 China |

A: 30 B: 30 |

A: 34.3 B: 34.6 |

1. At least one of the following conditions: (i) bilateral ovarian follicle ≤ 6; (ii) FSH ≥ 8 IU/L; (iii) E2 ≥ 293.6 pmol/L; (ⅳ) FSH/LH ≥2 2. Kidney deficiency |

1 cycle of menstruation | A) EA + SOP | B) SOP | 1) CPR 2) number of retrieved oocytes |

1) RR 1.5; 95% CI [0.61, 3.69], p = 0.38 2) MD 0.20; 95% CI [−0.39, 0.79], p = 0.51 |

n.r. |

| Zheng (2015)19 China |

A: 60 B: 60 C: 60 D: 60 |

A: 36.1 B: 36.9 C: 36.9 D: 37.0 |

At least one of the following conditions: (i) AFC in bilateral ovarian total ≤ 5; (ii) FSH ≥ 10 IU/L or FSH/LH ratio ≥ 3.6 detected at least twice, or ≥35 years old; (iii) a history of pelvic surgery |

3 cycles of menstruation | A) EA | B) Sham EA C) Artificial endometrial cycle treatment D) No treatment |

1) CPR 2) number of retrieved oocytes 3) AMH 4) AFC |

1) A vs B: RR 1.92; 95% CI [1.04, 3.54], p = 0.04 A vs C: RR 1.32; 95% CI [0.79, 2.21], p = 0.29 A vs D: RR 1.96; 95% CI [1.06, 3.62], p = 0.03 2) A vs B: MD 2.44; 95% CI [1.40, 3.48], p < 0.00001 A vs C: MD 0.34; 95% CI [−0.96, 1.64], p = 0.61 A vs D: MD 2.49; 95% CI [1.46, 3.52], p < 0.00001 3) A vs B: MD 0.59; 95% CI [0.35, 0.83], p < 0.00001 A vs C: MD 0.13; 95% CI [−0.14, 0.40], p = 0.35 A vs D: MD 0.57; 95% CI [0.33, 0.81], p < 0.00001 4) A vs B: MD 1.49; 95% CI [0.94, 2.04], p < 0.00001 A vs C: MD −0.35; 95% CI [−0.90, 0.20], p = 0.22 A vs D: MD 1.10; 95% CI [0.57, 1.63], p < 0.0001 |

A) mild allergy 2B) mild allergy 1C) mild lever function abnormalities 3, dizziness 7, fatigue 3 |

| Dong (2019)20 China | A: 25 B: 25 C: 25 D: 25 |

A: 33.9 B: 33.7 C: 34.0 D: 33.6 |

Those who meet 2 of following conditions or have history of POR twice: (i) ≥40 years old or history of pelvic surgery; (ii) AFC <7 (iii) history of POR |

3 cycles of menstruation | A) AT + Climen; + MOP |

B) Climen + MOP C) AT + MOP D) MOP |

1) AMH 2) AFC |

Not reported (only presented as Figures) |

n.r. |

AFC, antral follicle count; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; AT, acupuncture; CI, confidence interval; CPR, clinical pregnancy rate; E2, estradiol; EA, electro-acupuncture; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; Gn, Gonadotropin; IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer; LH, luteinizing hormone; MD, mean difference; MOP, microstimulation ovulation program; n.r., not reported; POR, poor ovarian response; RR, risk ratio; SOP, superovulation program.

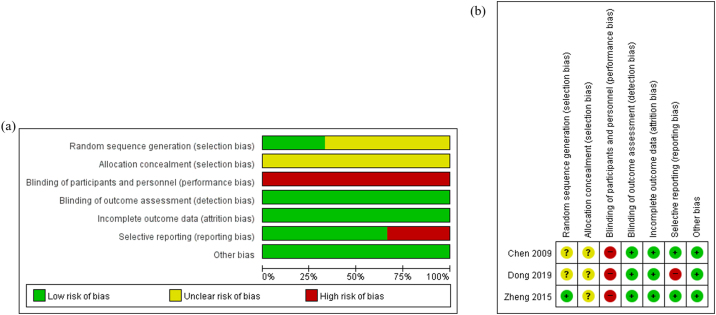

3.2. Risk of bias of included studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the RoB tool, which evaluates seven parameters. Since all RCTs were open-label trials, blinding of participants and investigators could not be achieved. There was no description about random sequence generation and allocation concealment in the Chen et al. study, and therefore selection bias in that study was ‘unclear’. Since a random table was used to generate random sequences in the Zheng et al. study, it was determined to be ‘low risk’. Reporting bias was assessed as ‘high risk’ in the Dong et al. study because results were only shown as figures without data. In all included studies, there was no detection or attrition bias from reviewing methods and results. In addition, other sources of bias such as improper funding did not exist. The details of the RoB are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Methodological quality graph. (A) Risk of bias graph: authors’ assessments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages of all included studies. (b): Risk of bias summary: authors’ assessments about each risk of bias item for each included study. “+”: low risk, “?”: unclear risk, and “-”: high risk.

3.3. Effectiveness of intervention

3.3.1. Primary outcome

CPR was measured in two trials,18, 19 and that of the intervention group was higher than the control group in both trials. Among the total 82 participants in the intervention groups, 31 (37.8%) succeeded to clinical pregnancy. By contrast, 44 (24.3%) of 181 women succeeded to clinical pregnancy in the control groups.

3.3.2. Secondary outcomes

The number of retrieved oocytes were evaluated in the Chen et al. and Zheng et al. studies. AMH and AFC was measured in the Zheng et al. and Dong et al. studies. The details of the results are shown in Table 1.

3.4. Adverse events

Adverse events were reported in one RCT,19 while the others18, 20 did not report any. There were three cases of mild fever function abnormalities, seven cases of dizziness, and three cases of fatigue in the artificial endometrial cycle group, which had taken Western medicines. By contrast, mild allergies were reported in two intervention group participants and one sham electro-acupuncture participant (Table 1).

4. Discussion

This review investigated the effectiveness of acupuncture for women with POR receiving IVF. Three studies18, 19 were included in this review, however, meta-analysis was not conducted because the study design differed between studies. A superovulation program with electroacupuncture was used as an intervention in the Chen et al. study,18 and a microstimulation ovulation program was used for all four groups in the Dong et al. study.20 According to the RCT in Dong et al., acupuncture and Climen was effective in improving the level of endocrine hormones and ovarian reservation function, however the results were only presented in figures, and therefore exact values could not be identified. In the Zheng et al. study,19 CRP, AMH, and the number of retrieved oocytes were highest in the electroacupuncture group, followed by the Western drug, sham electroacupuncture group, and no treatment group. AFC was slightly higher in the Western drug (Progynova and Duphaston) group than the intervention group. These drugs are used to treat conditions in menopause in which there is a lack of estrogen and progesterone.21 It is difficult to conclude that electroacupuncture is more effective than artificial endometrial cycle treatment for POR. However, electroacupuncture can be considered an alternative to hormone drugs in increasing the success rate of IVF.

All three RCTs conducted electroacupuncture treatment following menstrual and ovulatory cycles. CV4 and SP6 were selected as treatment acupoints in all studies, and CV3 and EX-CA1 (Zigong) were selected in two studies. CV4, CV3 and EX-CA1 are at the abdomen and SP6 is placed at the tibialis anterior muscle. Electroacupuncture of CV4 and SP6 can regulate uterus estradiol level and increase FSH, luteinizing hormone, and hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone levels in ovariectomized rat models.22 EX-CA1 (Zigong), which refers to the uterus in English, is the acupoint frequently used for treatment of uterine disorders. Additionally, no serious adverse events were reported after acupuncture, except mild allergies. Acupuncture is harmless to apply with IVF to improve infertility resulting from POR.

The inclusion criteria of patients in Zheng’s study was DOR, which referes to the normal physiological reduction in oocyte quantity and quality with advanced age.23 DOR belongs to POR, and there is POR that was induced not from DOR. For example, pelvic inflammation and surgery for ovarian cysts can lead to POR but not DOR.24, 25 Despite this, DOR was included in this review because it is clinically diagnosed similar to POR.26 Infertility is largely diagnosed with Kidney deficiency, as Kidney-essence is the base of reproduction in traditional Chinese medicine.27 From this perspective, Kidney deficiency may be related to POR, and therefore the Chen et al.18 study restricted patients to those with Kidney deficiency, to increase the effectiveness of acupuncture. Kidney deficiency syndrome scores were also improved in the intervention group compared to the control group after treatment in the Chen et al. study.

There are various causes of infertility in women, and treatment differs according to cause. This review focused on POR and the effectiveness of adding acupuncture to IVF. A previous related review examined the effectiveness of acupuncture for polycystic ovary syndrome patients undergoing IVF,28 and found that CPR in the acupuncture group was higher than the control group. CPR, the primary outcome of this review, is the most obvious indicator of pregnancy, however it is difficult to follow patients until delivery. Therefore, AMH, AFC, and the number of retrieved oocytes were selected as secondary outcomes to evaluate the improvement of POR.

This review has several limitations: First, meta-analysis could not be performed, and we were unable to draw conclusions. This review therefore failed to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture through the synthesis of study data. Second, there are limited previous data on acupuncture treatments for POR. Whether acupuncture can affect the secretion of AMH was not rigorously investigated in included studies. Third, since all included studies were conducted in China, there may be bias in drawing conclusions. Fourth, we did not search literature from Japanese databases.

In conclusion, the results of this systematic review suggest that acupuncture and electroacupuncture may improve the quality of oocytes and increase the pregnancy rate in women with POR. However, more studies are needed to determine the association between acupuncture and POR-related outcome measures.

Author contributions

Conception: SY and SJ. Methodology: SJ and KHK. Formal Analysis: SJ and KHK. Investigation: SJ and KHK. Writing - Original Draft: SJ and KHK. Writing - Review & Editing: JHJ and SY. Supervision: SY.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding

This article was supported by the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KSN2013240).

Ethics statement

Not applicable

Data availability

The data used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Footnotes

Supplementary Table S1. Basic characteristics of included randomized clinical trials and Table S2. Detailed information of acupuncture treatments: following STRICTA can be found in the online version at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2020.02.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Irvine D.S. Epidemiology and aetiology of male infertility. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(Suppl 1):33–44. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.suppl_1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindsay T.J., Vitrikas K.R. Evaluation and treatment of infertility. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(5):308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakamoto A., Kamada Y., Kotani S., Yamada K., Kimata Y., Hiramatsu Y. In vitro fertilization and pregnancy management in a woman with acquired idiopathic chylous ascites. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jog.13434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park H.J., Lee G.H., Gong du S., Yoon T.K., Lee W.S. The meaning of anti-Mullerian hormone levels in patients at a high risk of poor ovarian response. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2016;43(3):139–145. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2016.43.3.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen Y., Tannus S., Alzawawi N., Son W.Y., Dahan M., Buckett W. Poor ovarian response as a predictor for live birth in older women undergoing IVF. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;36(4):435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferraretti A.P., La Marca A., Fauser B.C. ESHRE consensus on the definition of’ poor response’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: The Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1616–1624. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Marca A., Sighinolfi G., Radi D. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART) Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(2):113–130. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klinkert E.R., Broekmans F.J.M., Looman C.W.N., Habbema J.D.F., te Velde E.R. The antral follicle count is a better marker than basal follicle-stimulating hormone for the selection of older patients with acceptable pregnancy prospects after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(3):811–814. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lgn Ying Cheong, Rutherford Tony, Ledger William. Acupuncture and herbal medicine in in vitro fertilisation: A review of the evidence for clinical practice. Hum Fertil. 2010;13(1):3–12. doi: 10.3109/14647270903438830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho M., Huang L.C., Chang Y.Y. Electroacupuncture reduces uterine artery blood flow impedance in infertile women. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48(2):148–151. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60276-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stener-Victorin E., Waldenstrom U., Andersson S.A., Wikland M. Reduction of blood flow impedance in the uterine arteries of infertile women with electro-acupuncture. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(6):1314–1317. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan C.C., Ng E.H., Li C.F., Ho P.C. Impaired ovarian blood flow and reduced antral follicle count following laparoscopic salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(10):2175–2180. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qian Y., Xia X.R., Ochin H. Therapeutic effect of acupuncture on the outcomes of in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(3):543–558. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4255-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen C., Wu M., Shu D., Zhao X., Gao Y. The role of acupuncture in in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2015;79(1):1–12. doi: 10.1159/000362231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manheimer E., van der Windt D., Cheng K. The effects of acupuncture on rates of clinical pregnancy among women undergoing in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(6):696–713. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacPherson H., Altman D.G., Hammerschlag R. Revised STandards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (STRICTA): Extending the CONSORT statement. Acupunct Med. 2010;28(2):83–93. doi: 10.1136/aim.2009.001370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J., Liu L.L., Cui W., Sun W. [Effects of electroacupuncture on in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET) of patients with poor ovarian response] Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2009;29(10):775–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Y., Feng X., Mi H. Effects of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on ovarian reserve of patients with diminished ovarian reserve in in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer cycles. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(12):1905–1911. doi: 10.1111/jog.12810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong X.L., Ran J.K., Zhang H.J., Chen K., Li H.X. [Acupuncture combined with medication improves endocrine hormone levels and ovarian reserve function in poor ovarian response patients undergoing in vitro fertilization-embryo transplantation] Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2019;44(8):599–604. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.180779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhl H. Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: Influence of different routes of administration. Climacteric. 2005;8(Suppl 1):3–63. doi: 10.1080/13697130500148875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng K.T.S. [Effects of preventive-electroacupuncture of "Guanyuan" (CV 4) and "Sanyinjiao" (SP 6) on hypothalamus-pituitary-ovary axis in ovariectomized rats] Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2012;37(1):15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharara F.I., Scott R.T., Jr, Seifer D.B. The detection of diminished ovarian reserve in infertile women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(3 Pt 1):804–812. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molloy D., Martin M., Speirs A. Performance of patients with a "frozen pelvis" in an in vitro fertilization program. Fertil Steril. 1987;47(3):450–455. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nargund G., Cheng W.C., Parsons J. The impact of ovarian cystectomy on ovarian response to stimulation during in-vitro fertilization cycles. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(1):81–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastore L.M., Christianson M.S., Stelling J., Kearns W.G., Segars J.H. Reproductive ovarian testing and the alphabet soup of diagnoses: DOR, POI, POF, POR, and FOR. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(1):17–23. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1058-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lian F., Wu H.C., Sun Z.G., Guo Y., Shi L., Xue M.Y. Effects of Liuwei Dihuang Granule ([symbols; see text]) on the outcomes of in vitro fertilization pre-embryo transfer in infertility women with Kidney-yin deficiency syndrome and the proteome expressions in the follicular fluid. Chin J Integr Med. 2014;20(7):503–509. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1712-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Junyoung Jo Y.J.L. Effectiveness of acupuncture in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med. 2017;35:162–170. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2016-011163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.