TO THE EDITOR:

Opioids are widely overprescribed after surgery.1 Leftover medication is often diverted into the community, contributing to the opioid epidemic.2 The lack of evidence regarding ideal prescribing practice after surgery may hinder efforts to reduce overprescribing.3 In this study, we developed and disseminated postoperative prescribing guidelines and measured the impact on prescribing in a statewide hospital collaborative.

The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC) is a statewide quality improvement collaborative that maintains a clinical registry of general, vascular, and gynecologic operations, capturing a random sample of 50,000 patients per year. From January to September 2017, MSQC collected patient-reported opioid consumption after surgery. In partnership with the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network (Michigan OPEN), these data were used to develop prescribing guidelines for nine operations (see supplemental appendix).4 In October 2017 these guidelines were communicated to MSQC clinicians via in-person presentations and electronic distribution.

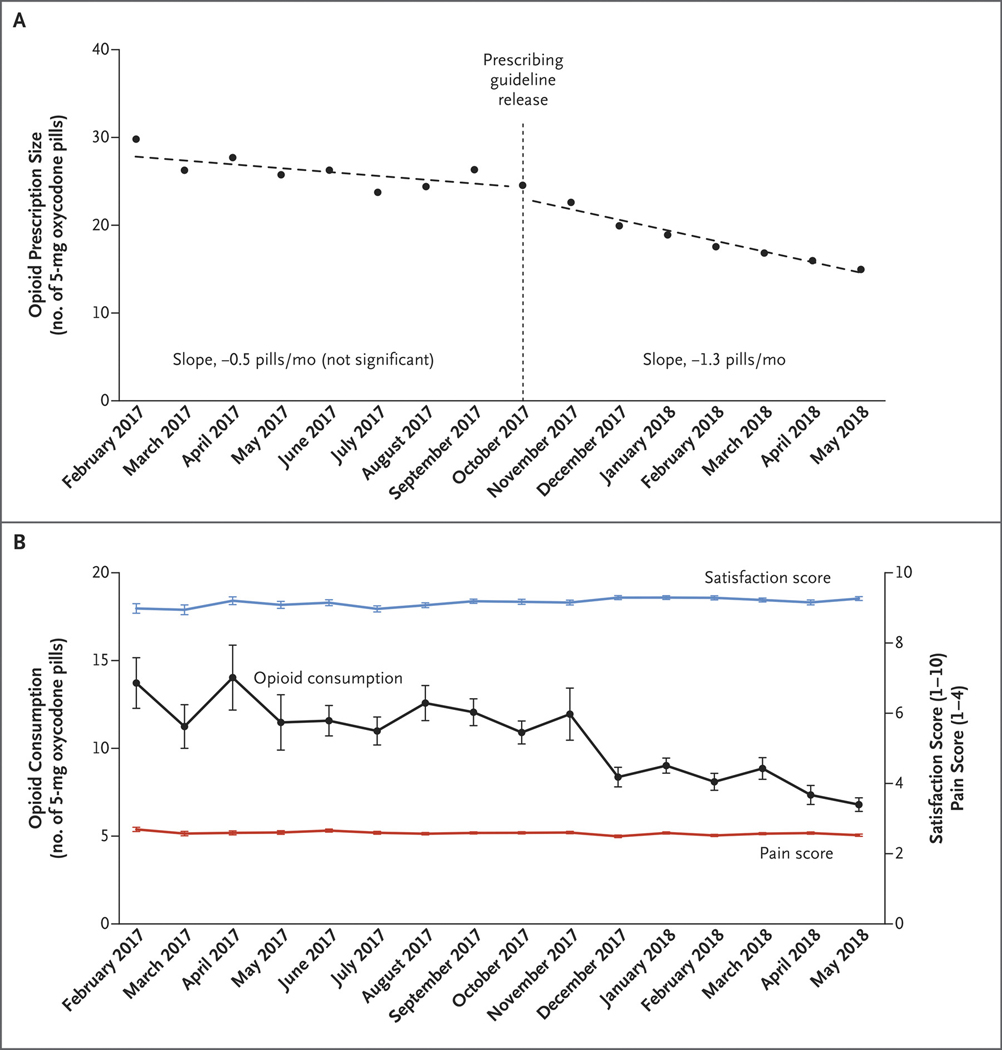

An interrupted time-series analysis was conducted to compare postoperative opioid prescribing before and after guideline release. The primary outcome was opioid prescription size, represented in pills of 5 mg oxycodone. We collected patient-reported outcomes (PROs) as secondary outcomes, including opioid consumption, satisfaction on a scale of 0 (“extremely dissatisfied”) to 10 (“extremely satisfied”), and pain score in the first week after surgery (1 = “no pain”, 2 = “minimal pain”, 3 = “moderate pain”, and 4 = “severe pain”).

We analyzed prescription data from 11,716 patients across 43 hospitals, collected from February 2017 to May 2018. 6718 (57%) of patients were female and mean (SD) age was 52.1 (16.3) years. 6,585 (56%) patients completed PRO surveys. Before guideline release, there was no significant change in prescription size over time (slope: −0.5 pills/month, 95% CI −1.1 – 0.06). After guideline release, prescription size decreased by −1.3 pills/month (95% CI −1.6 - −1.0). This represented a significant difference in slope of −0.8 pills/month (95% CI −1.5 to −0.12, P=0.024) between the pre- and post-guideline periods (Figure 1A). Mean (SD) prescription size decreased from 26 (2) pills in the pre-guideline period to 18 (3) pills after the guidelines (difference: 8 pills, 95% CI 6 – 11). Opioid consumption also decreased from 12 (1) to 9 (2) pills (difference: 3 pills, 95% CI 2 – 5), possibly due to patients anchoring and adjusting their expectations for opioid use to smaller prescriptions.5 Despite the reductions in prescription size and opioid use, satisfaction and pain score were clinically unchanged (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Opioid Prescription Size and Consumption before and after Release of the Prescribing Guidelines. Panel A shows the interrupted time-series analysis of postoperative opioid prescription size. After the prescribing guidelines were released in October 2017, prescription size declined significantly. The change in the slope (i.e., the change in the rate of the decrease in prescription size, measured as 5-mg pills of oxycodone per month) from before the guideline release to after guideline release was also significant (P=0.02). Panel B shows patient-reported opioid consumption among the 6585 patients who completed surveys for the analysis of patient-reported outcomes. Opioid consumption decreased by 50% over the study period, while patient-reported satisfaction with care and pain in the week after surgery remained clinically stable. The satisfaction score ranged from 0 (“extremely dissatisfied”) to 10 (“extremely satisfied”), and the pain score ranged from 1 (“no pain”) to 4 (“severe pain”).

This is not the only effort to address the opioid crisis in Michigan. Most notably, Public Act 251 legislatively limited prescription size starting in June, 2018. Importantly, however, this law did not go into effect until after the study period. In conclusion, evidence-based prescribing guidelines reduced postoperative opioid prescription size across a statewide population without negatively impacting patient satisfaction or pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Joceline Vu receives funding for research from the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1F32DK115340–01A1). Dr. Howard receives funding from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation. Drs. Brummett, Waljee, and Englesbe receive funding for research from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA042859). Dr. Brummett consults for Heron Therapeutics. Dr. Englesbe receives partial salary support from Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan through the Michigal Surgical Quality Collaborative. This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA042859).

References

- 1.Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of Opioid Prescribing With Opioid Consumption After Surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg. 2018:e184234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipari RN and Hughes A. How people obtain the prescription pain relievers they misuse. The CBHSQ Report: January 12, 2017. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD: Accessed April 7, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waljee JF, Li L, Brummett CM, Englesbe MJ. Iatrogenic Opioid Dependence in the United States: Are Surgeons the Gatekeepers? Annals of surgery. 2017;265(4):728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michigan Opioid Prescribing and Engagement Network. Opioid Prescribing Recommendations for Surgery. https://opioidprescribing.info. Published October 2017. Accessed April 7, 2019.

- 5.Epley N, Gilovich T. The anchoring-and-adjustment heuristic: why the adjustments are insufficient. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(4):311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.