Abstract

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR kinase pathway is extensively deregulated in human cancers. One critical node under regulation of this signaling axis is eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4F, a complex involved in the control of translation initiation rates. eIF4F-dependent addictions arise during tumor initiation and maintenance due to increased eIF4F activity—generally in response to elevated PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling flux. There is thus much interest in exploring eIF4F as a small molecule target for the development of new anticancer drugs. The DEAD-box RNA helicase, eIF4A, is an essential subunit of eIF4F, and several potent small molecules (rocaglates, hippuristanol, pateamine A) affecting its activity have been identified and shown to demonstrate anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo in preclinical models. Recently, a number of new small molecules have been reported as having the capacity to target and inhibit eIF4A. Here, we undertook a comparative analysis of their biological activity and specificity relative to the eIF4A inhibitor, hippuristanol.

Keywords: translation initiation, eIF4A, RNA helicase, eIF4F, hippuristanol

INTRODUCTION

Translation, the most energetically expensive process in the cell, plays a major role in gene expression. Dysregulation of this process perturbs several critical cellular networks and can facilitate the establishment of multiple cancer hallmarks including resistance to cell death, activation of invasion and metastasis, induction of angiogenesis, enablement of replicative immortality, deregulated cellular energetics, and altered immune responses and inflammation (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011; Bhat et al. 2015). Perturbations that increase the activity or availability of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4E, a cap-binding protein involved in recruiting ribosomes to mRNA, can selectively stimulate translation of mRNAs that play critical roles in the aforementioned hallmarks to drive tumorigenesis in appropriate contexts (Lazaris-Karatzas et al. 1990; Ruggero et al. 2004; Wendel et al. 2004). eIF4E is a subunit of the heterotrimeric eIF4F complex and associates with the eIF4G subunit; the latter acting as a scaffold that recruits 43S preinitiation complexes (PICs) to mRNAs. The eIF4A DEAD-box RNA helicase subunit is a critical component of eIF4F and is required to remodel mRNA 5′ leaders in preparation of 43S PIC binding. Mammalian cells encode two eIF4A paralogs, eIF4A1 and eIF4A2, that share ∼90% identity at the amino acid level (Nielsen and Trachsel 1988). Although both eIF4A proteins can exchange into the eIF4F complex, eIF4A1 is essential for cell viability whereas eIF4A2 is not (Yoder-Hill et al. 1993; Galicia-Vazquez et al. 2015).

Elevation of c-MYC levels or activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway increases eIF4F levels and leads to selective translation stimulation of many pro-oncogenic mRNAs (Lin et al. 2008). In turn, translation of c-Myc mRNA is eIF4F-dependent and targeting eIF4F is a powerful way of down-regulating MYC (Robert et al. 2014). Inhibiting eIF4E is synthetic lethal with MYC overexpression, offering a unique therapeutic opportunity for drugging MYC-dependent tumors (Lin et al. 2012; Pourdehnad et al. 2013). There is thus much interest in strategies by which to inhibit eIF4F in cancer, and the feasibility of this approach has been borne out by experiments undertaken by several groups (Bhat et al. 2015). Delivery of eIF4E-targeting antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) in mouse xenograft models curtails tumor growth and the underlying angiogenic supporting network (Graff et al. 2007). The generation of transgenic mice expressing inducible shRNAs capable of systemically reducing eIF4E levels showed that chronic, global suppression of eIF4E is well tolerated at the organismal level (Lin et al. 2012). Small molecules that inhibit eIF4F activity have been identified from high-throughput screens, and among the more potent ones are those that target eIF4A—namely hippuristanol (Hipp), rocaglates, and pateamine A (Cencic et al. 2012; Bhat et al. 2015; Chu and Pelletier 2015).

Hipp (Fig. 1A) has been shown to bind to the eIF4A carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) and inhibit RNA interaction by stabilizing eIF4A in a closed conformation (Bordeleau et al. 2006; Lindqvist et al. 2008; Sun et al. 2014). Its binding site is not conserved among other DEAD-box RNA helicases, making it a selective eIF4A inhibitor (Lindqvist et al. 2008). In contrast, pateamine A and rocaglates stabilize RNA-bound eIF4A and deplete eIF4A from the eIF4F complex (Bordeleau et al. 2005, 2008; Low et al. 2005; Cencic et al. 2009; Iwasaki et al. 2016). All three classes of compounds have been tested in several preclinical cancer models and display single agent activity, have the ability to resensitize drug-resistant tumor cells to chemotherapy, and are tolerated in vivo (Bordeleau et al. 2008; Kuznetsov et al. 2009; Cencic et al. 2013; Chu and Pelletier 2015). Through the identification and characterization of an eIF4A1 rocaglate-resistant allele, the anticancer activity of rocaglates has been genetically linked to eIF4A1 target engagement (Chu et al. 2016; Iwasaki et al. 2019). There is thus much interest in developing eIF4A inhibitors as potential anticancer agents.

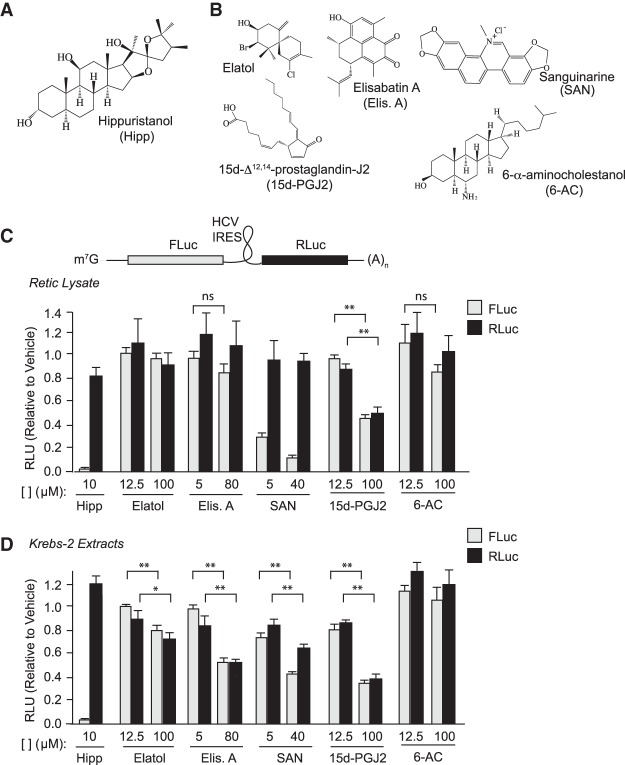

FIGURE 1.

Assessing activity of candidate eIF4A inhibitors in vitro. (A) Structure of hippuristanol. (B) Structure of compounds recently reported to target eIF4A1 and tested in this study. (C) Assessment of cap- and HCV IRES-mediated translation in the presence of the indicated compound concentrations in RRL. Luciferase activity results are expressed relative to values obtained in the presence of vehicle controls. n = 3 biological replicates performed in duplicates. ±SEM. ns, P > 0.05; (**) P < 0.01 (nonparametric Mann–Whitney test). (D) Assessment of cap- and HCV IRES-mediated translation in the presence of the indicated compound concentrations in Krebs-2 extracts. Luciferase activity results are expressed relative to values obtained in the presence of vehicle controls. n = 3 biological replicates performed in duplicates. ±SEM. ns, P > 0.05; (*) 0.01 < P < 0.05; (**) P < 0.01.

Several recent reports have emerged reporting on new small molecule inhibitors of eIF4A (Fig. 1B). The marine natural product, elatol, was first isolated as a cytotoxic compound and subsequently reported to inhibit eIF4A1-mediated ATP hydrolysis in vitro (Peters et al. 2018). However, elatol also induces robust phosphorylation of eIF2α in MEFs, making it difficult to directly link any in cellula activity of elatol to eIF4A1 inhibition (Peters et al. 2018). Elisabatin A (Elis. A) was also identified as an inhibitor of eIF4A1 ATPase activity in vitro (Tillotson et al. 2017). The prostaglandin, 15d-PGJ2, has been reported to inhibit translation and when immobilized on a solid support matrix was able to capture eIF4A1 (but not eIF4G1) from cytoplasmic extracts, suggesting that it interferes with eIF4A:eIF4G interaction (Kim et al. 2007; Yun et al. 2018). The antifungal agent, 6-aminocholestanol (6-AC), was identified following virtual docking simulations as a potential inhibitor of mammalian and Leishmania eIF4A1 (Abdelkrim et al. 2018; Harigua-Souiai et al. 2018). In vitro testing found that 6-AC blocked the ATPase and helicase activity of mammalian and Leishmania (Li) eIF4A1 (Abdelkrim et al. 2018; Harigua-Souiai et al. 2018). Lastly, sanguinarine (SAN) has recently been reported to inhibit eIF4A1 ATPase and helicase activity (Jiang et al. 2019). With such an abundance of new eIF4A inhibitors, we sought to compare the selectivity and potency of these compounds.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We first tested the activity of the compounds shown in Figure 1B in in vitro translation extracts utilizing a FF/HCV/Ren bicistronic mRNA reporter (Fig. 1C, top panel). The HCV IRES serves as an internal control in these experiments since its initiation is not dependent on any of the three eIF4F subunits (Fraser and Doudna 2007). In rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL), Hipp (10 µM) potently inhibited cap-dependent FLuc output while having no effect on HCV IRES-driven RLuc production (Fig. 1C; Supplemental Table S1), as previously reported (Bordeleau et al. 2006). Elatol and elisabatin A had little effect on FLuc or RLuc production when present in extracts at final concentrations of 12.5 or 100 µM (Fig. 1C). SAN inhibited FLuc at 5 and 40 µM (Fig. 1C). 15d-PGJ2 blocked expression of both cap- and HCV IRES-mediated translation at 100 µM. 6-AC had no effect on FLuc or RLuc output at 100 µM (Fig. 1C). The compounds were also tested in translation extracts prepared from murine Krebs-2 cells (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Table S1). Here, elisabatin A reduced both FLuc and RLuc by ∼50% at 80 µM (Fig. 1D). The effects of SAN on FLuc and RLuc expression in Krebs-2 extracts were not as pronounced as in RRL, but nevertheless expression of both luciferases was inhibited at 40 µM compared to 5 µM (Fig. 1D). 15d-PGJ2 blocked expression of both cap- and HCV IRES-mediated translation at 100 µM in Krebs-2 extracts (Fig. 1D). As in RRL, 6-AC had little effect on FLuc or RLuc activity in Krebs-2 extracts (Fig. 1D). With the exception of Hipp or SAN in RRL, these results are not what would be expected for a selective eIF4A inhibitor.

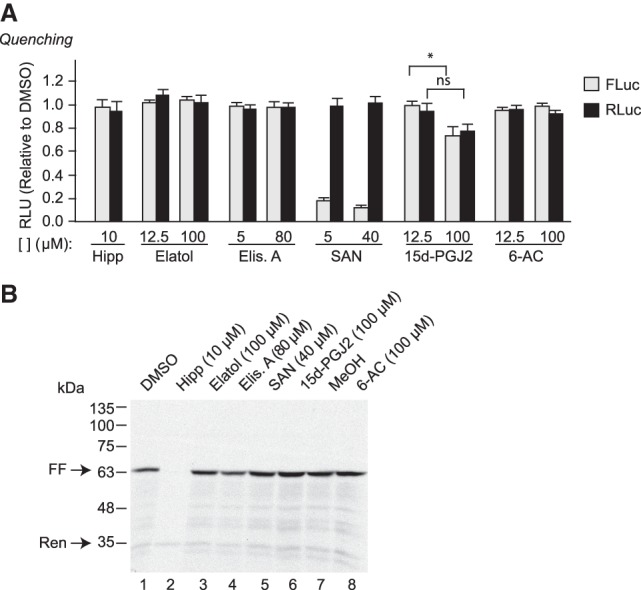

A recognized shortcoming of using luciferase as a readout in vitro for assessing the consequences of small molecules on translation is that some compounds can quench the luciferase reaction, or inactivate FLuc enzyme, thus scoring as false-positives in bioluminescent assays (Novac et al. 2004). We therefore directly assessed the ability of compounds to quench FLuc and RLuc activity (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Table S1). For these experiments, FLuc and RLuc are first produced in vitro from the FF/HCV/Ren mRNA, translation is then blocked by the addition of the elongation inhibitor cycloheximide, the compound of interest is then added, and FLuc and RLuc activities are measured 15 min later. Among the compounds sampled, SAN quenched FLuc activity at both concentrations tested, and 15d-PGJ2 modestly inhibited FLuc output at 100 µM (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that the inhibition seen in Figure 1 with SAN on FLuc is likely due to quenching. 15d-PGJ2 showed modest FLuc quenching at 100 µM, but its behavior in this assay cannot explain the potent inhibition seen in in vitro translation extracts (Fig. 1C,D).

FIGURE 2.

Assessment of luciferase quenching activity. (A) Quenching assays were performed by first translating FF/HCV/Ren mRNA in RRL for 1 h, after which cycloheximide (10 µg/mL) was added to stop the reaction. Compounds were then added to the RRL at the indicated final concentrations, incubated at 30°C for an additional 15 min, after which time FLuc and RLuc activity were measured. Luciferase activity results are calculated relative to values obtained in the presence of vehicle controls and are expressed as the mean of three biological replicates performed in duplicates. ±SEM. ns, P > 0.05; (*) 0.05 > P > 0.01. (B) Production of [35S]-FLuc and [35S]-RLuc following in vitro translation of FF/HCV/Ren mRNA in the presence of the indicated compound concentrations. Following translations, samples were processed in Laemmli sample buffer and electrophoresed through an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was treated with EN3Hance, dried and exposed to X-Omat (Kodak) film. The arrows indicate the position of migration of FLuc and RLuc proteins.

To more directly assess the effects of these compounds on translation, we monitored product formation through the incorporation of 35S-Met into FLuc and RLuc in vitro as this provides a readout independent of enzyme activity (Fig. 2B). FLuc is visualized as a molecular species at 62 kDa, whereas RLuc is 36 kDa. As previously reported, Hipp inhibits production of FLuc, but not RLuc (Fig. 2B, compare lane 2 to 1; Bordeleau et al. 2006). None of the other tested compounds significantly inhibited incorporation of 35S-Met into FLuc or RLuc proteins indicating that under these conditions they are not affecting eIF4A1 activity to block translation (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 3–6 to 1 and 8 to 7).

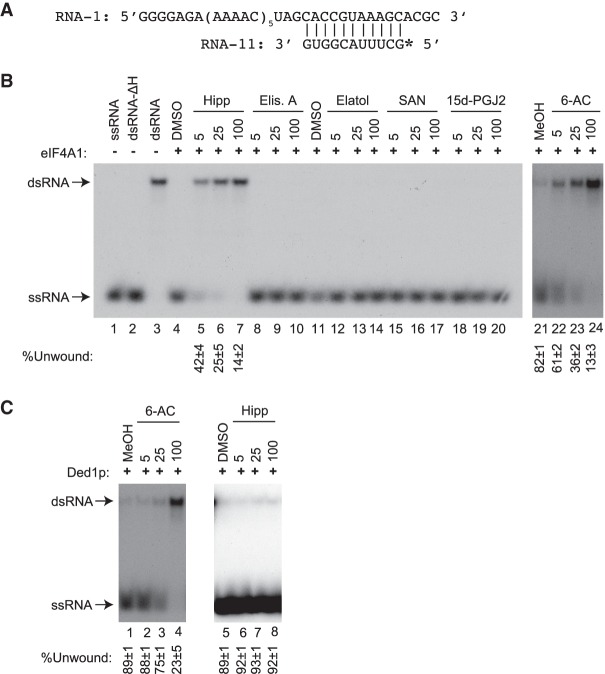

We then sought to assess the behavior of these compounds on eIF4A1-mediated helicase activity using a classic gel-based assay that resolves duplexed RNA substrate from single-stranded, unwound product (Rozen et al. 1990; Rogers et al. 1999). This assay is information-rich as it can identify inhibitors that would impair RNA or ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis, or hinder conformational changes during the unwinding process. As well, direct visualization of the RNA substrates and products is powerful as it provides a quality assurance step that ensures substrate/product relationships are maintained. For example, contamination of an eIF4A preparation by a ribonuclease or phosphatase would result in loss of label on the substrate (dsRNA) with no or sub-stoichiometric amounts of product generated (ssRNA). These problems are not readily detected in solution-based helicase assays that rely solely on gains in fluorescence as readout from a quenched dsRNA substrate (Sommers et al. 2019). The RNA duplex used as substrate in our assay has been previously described and has a ΔG of −17.9 kcal/mol (Fig. 3A; Rogers et al. 1999). Hipp inhibited eIF4A1 helicase activity, as previously documented (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 5–7 to 4) (Bordeleau et al. 2006). Elisabatin A, elatol, SAN, and 15d-PGJ2 had no effect on eIF4A1 helicase activity up to concentrations of 100 µM (Fig. 3B, lanes 8–20). Only 6-AC inhibited eIF4A1 helicase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 22–24 to 21). However, this effect was not specific to eIF4A1 since 6-AC also blocked Ded1p activity, a yeast DEAD-box helicase (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 2–4 to 1). Surprisingly, 6-AC had little effect in translation extracts (Fig. 1C,D), a result that could indicate promiscuous binding to multiple targets and titration away from eIF4A1 in the more complex setting of in vitro translation assays. In characterizing the effects of 6-AC on the helicase activity of murine and LieIF4A, Abdelkrim et al. (2018) observed significant “helicase activity” in the absence of ATP, a result that is inconsistent with the absolute dependency of eIF4A1 on ATP for enzymatic activity (Rogers et al. 1999)—raising the question of what exactly was being affected by 6-AC in these previous assays. Taken together, these results indicate that among the tested compounds, only Hipp displayed a behavior consistent with it being a selective eIF4A inhibitor.

FIGURE 3.

Assessing effects of compounds on eIF4A1 helicase activity. (A) Sequence of RNA duplex used in this study. The asterisk at the 5′ end of RNA-11 denotes the location of the 32P-label. (B) Double-stranded (dsRNA) unwinding activity of eIF4A1 in the presence of the indicated compound concentrations. The position of migration of the RNA duplex and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) molecules is indicated to the left of the panels. Single-stranded RNA-11 was loaded in lane 1 in the absence of eIF4A. Denatured dsRNA (ΔH: performed at 95°C) was loaded in lane 2 (dsRNA-ΔH) and nondenatured dsRNA was loaded in lane 3 (dsRNA). Results are representative of two biological replicates ± SEM. (C) Unwinding activity of Ded1p in the presence of 6-AC or Hipp. n = 2 ± SEM.

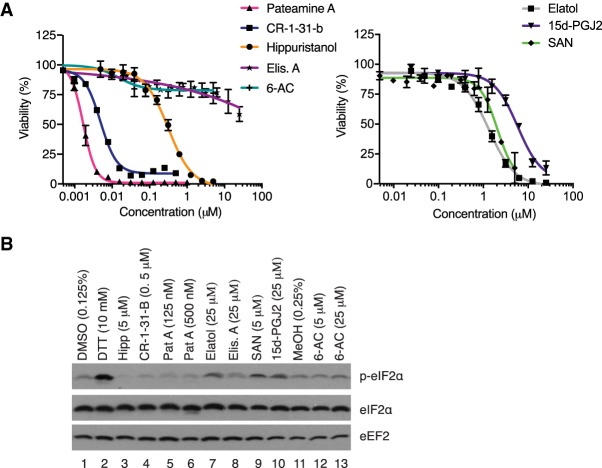

We have previously shown that JJN-3 multiple myeloma cell viability is compromised when exposed to rocaglate, silvestrol, or Hipp (Robert et al. 2014). We found that the most potent compounds were pateamine A (IC50 = ∼2 nM), CR-1-31-B (IC50 = 5 nM), and Hipp (IC50 = ∼0.3 µM) (Fig. 4A). Elisabatin A and 6-AC displayed little bioactivity in this assay (Fig. 4A, left panel). Elatol (IC50 = ∼1.3 µM) and SAN (IC50 = ∼2 µM) were ∼4–6 times less potent than Hipp, whereas 15d-PGJ2 (IC50 = ∼6 µM) was ∼20 times less potent than Hipp (Fig. 4A, right panel). A similar rank order was observed with these compounds toward A549 lung cancer cells (Supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 4.

Assessing the response of JJN3 cells to putative eIF4A inhibitors. (A) JJN3 cells were treated with increasing doses of the indicated compounds for 48 h. Viability was measured using the CellTiter Glo assay. Results are expressed relative to vehicle-treated cells. n = 3 ± SEM. (B) Assessing eIF2α phosphorylation status in JJN-3 cells exposed to the indicated compound concentrations for 90 min. Western blots were probed with antibodies targeting the proteins indicated to the right.

Many compounds can nonspecifically inhibit protein synthesis through activation of the integrated stress response (ISR), an adaptive cellular mechanism that permits cells to respond to, and survive, stress (Pakos-Zebrucka et al. 2016). At the core of this pathway is phosphorylation of eIF2α (performed by one of four kinases) which serves to dampen global protein synthesis while permitting the expression of a select choice of mRNAs. Since elatol has previously been shown to activate the ISR (Peters et al. 2018), we wished to assess this in JJN-3 cells and determine if any other compound also activated this response. DTT is a potent inducer of the ISR and served as a positive control in this assay (Fig. 4B, compare lane 2 to 1). Neither Hipp, the rocaglate CR-1-31-B, nor pateamine A induced eIF2α phosphorylation (compare lanes 3–6 to 1). Elatol, SAN, and 15d-PGJ2 all induced eIF2α phosphorylation (compare lanes 7–10 to 1), whereas elisabatin A and 6-AC did not.

In sum, with the exception of Hipp, the results we obtained are not what would be expected for an eIF4A inhibitor. Indeed, SAN is known to have quite promiscuous bioactivity—with effects ranging from antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, proapoptotic and growth inhibitory activities on tumor cells (Galadari et al. 2017). It nonspecifically inhibits a large number of cellular processes and biological targets, among which are quadruplexes of human telomeres and of the c-MYC promoter (Ghosh et al. 2013), the PTP1B phosphatase (Zeder-Lutz et al. 2012), Stat3 (Sun et al. 2012), Bcl-XL (Bernardo et al. 2008), mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (Vogt et al. 2005), and NF-κB (Chaturvedi et al. 1997). It thus appears that SAN is likely a pan-assay interference compound (PAIN) (Baell and Holloway 2010).

15d-PGJ2 is a cyclopentenone prostaglandin possessing α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups that can favor Michael addition reactions to form covalent adducts with exposed nucleophiles, such as presented by cysteine thiol residues and 15d-PGJ2 has been shown to interact with eIF4A1 Cys264 (Kim et al. 2007). Perhaps this explains why 15d-PGJ2 inhibits FLuc in vitro when assessing translation via luciferase readout (Fig. 1C,D) (but no quenching activity) versus no effect when [35S]-Met incorporation is used to monitor translation (Fig. 2B). We have previously observed this behavior when characterizing hits from a previous high-throughput screening assay for translation inhibitors (Novac et al. 2004) and postulate it might be a consequence of a compound interfering with protein folding during synthesis—in which case enzymatic-based readouts score these as false-positives. The large target spectrum of 15d-PGJ2 is borne out by a recent proteomic study of endothelial cells exposed to 5 µM 15d-PGJ2 for 4 h (far below the concentration at which effects on translation are reported), where 358 target proteins were identified, among which were many initiation (eIF4A1, eIF4G1, eIF4G3, eIF3B eIF3D, eIF3H, eIF3F) and elongation (EF1D, EF2, EF1G, mitochondrial EF-Tu) translation factors (Marcone and Fitzgerald 2013). The physiological concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 in body fluids has been reported to be in the nanomolar range—far lower than the concentrations required to inhibit translation in vitro (Morgenstern et al. 2018).

Elatol has been reported to inhibit eIF4A1 ATPase activity and has a 2:1 binding stoichiometry to eIF4A1 with a KD of 2 µM in vitro (Peters et al. 2018). It is cytotoxic to cells, a property that we have confirmed (Fig. 4A; Peters et al. 2018). Elatol inhibits gene expression but there is no evidence that it does so in cellula by primarily targeting eIF4A1. Oddly, exposure of cells to 2 µM elatol for 2 h caused no significant change in translating polysomes (Peters et al. 2018), an effect that should have been immediate and pronounced (as observed with silvestrol in that same experiment), if eIF4A1 were the primary target. Rather, extended periods of exposure time (8–16 h) were required to observe inhibition of polysomes and cap-dependent translation. Since translational responses to inhibitors are very rapid (5–15 min), it becomes difficult to ascertain if the reported inhibition of translation by elatol occurring 8 h following compound exposure is not a secondary consequence of other processes being targeted (Peters et al. 2018). Elatol has been reported to robustly phosphorylate eIF2α (Peters et al. 2018) (a result we have confirmed, see Fig. 4A) and this, in and of itself, could explain the translation inhibitory activity of this compound in cells. In our hands, elisabatin A did not show any activity that would suggest it to be a translation inhibitor. Allolaurinterol has also been reported to be an inhibitor of eIF4A1 (Tillotson et al. 2017) but due to limitations in compound availability, we have been unable to assess its activity as a translation initiation inhibitor.

We are concerned about the reproducibility of some of the assays that were used to identify and/or characterize the activity of the compounds described herein. Firstly, as far as we can assess, previous studies that identified elatol, elisabatin A, and 6-AC as eIF4A1 inhibitors used the malachite green-based assay to score for inhibition of ATPase activity. The recombinant eIF4A1 preparations used in several of these studies are reported to have been isolated via a single affinity chromatography step—taking advantage of an engineered His6 tag (Abdelkrim et al. 2018; Harigua-Souiai et al. 2018; Peters et al. 2018). Although the increase in specific activity following immobilized metal-affinity purification (IMAC) can be extremely high, it does not yield protein preparations that are free of contaminants. For example, endogenous bacterial proteins containing adjacent histidine residues will be copurified (Bornhorst and Falke 2000). Case in point, E. coli RNA chaperone Hfq is a hexamer that harbors four histidine residues per subunit and is a known contaminant of IMAC purifications (Milojevic et al. 2013). Since, eIF4A1 has a weak catalytic ATP turnover rate (kcat: ∼1–3/min) (Lorsch and Herschlag 1998), even a minor contaminant with a high kcat could confuse interpretation of the results (for example, if a compound under study inhibited the contaminant). In our hands, we have found it more rigorous when purifying eIF4A1 to include, at a minimum, an additional ion exchange chromatography step, following the IMAC step. It may also be that some of the reported activities of these compounds (Fig. 1B) are context-dependent. In sum, although some of the compounds tested herein (Fig. 1B) have been reported to bind to eIF4A1 or interfere with eIF4A1 activity, until genetic evidence is obtained linking physiological responses to eIF4A1 inhibition, we urge caution in using these as reagents to selectivity probe for eIF4A1 activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds

The synthesis of Hipp has been previously described (Somaiah et al. 2014). Elatol was synthesized as previously described and was a kind gift from Tyler Fulton, Carina Jette, and Dr. Brian Stoltz (Caltech) (White et al. 2008). Sanguinarine and 15d-Δ12,14-prostaglandin-J2 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience and Enzo Life Sciences, respectively. Elisabatin A was purified from the West Indian sea whip as previously described (Rodríguez et al. 1999). 6-α-aminocholestanol was custom synthesized by Toronto Research Chemicals. All compounds were resuspended in DMSO, with the exception of 6-α-aminocholestanol which was in methanol. All stocks were stored at −80°C.

Cell viability assays

JJN3 cells were maintained in RPMI media supplemented with 10% BGSS. For viability assays, JJN3 cells were seeded at 500,000 cells/mL in 96-well plates with the indicated drug concentrations for 48 h. Cell viability was determined using CellTiterGlo (Promega). IC50 values of each drug were assessed using a four-parameter nonlinear curve-fit regression with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software).

In vitro transcriptions and translations

In vitro translation assays were performed in rabbit reticulocyte (RRL) or Krebs-2 extracts as previously described (Novac et al. 2004). Briefly, linearized pSP/FF/HCV/Ren DNA template was transcribed in vitro using SP6 RNA polymerase (NEB). Capped FF/HCV/Ren mRNA was used at a final concentration of 5–10 µg/mL in RRL and Krebs-2 extracts. Firefly and renilla enzymatic activities were assessed on a Berthold Lumat LB 9507 luminometer (Berthold technologies). [35S]-methionine (1175 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer) was used to monitor production of newly synthesized luciferase proteins in RRL. Proteins were separated on SDS/10% polyacrylamide gels, which were subsequently treated with EN3Hance, dried, and exposed to film (Kodak).

Purification of recombinant eIF4A1

Recombinant mouse His6-eIF4AI protein was expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS. Transformed bacteria were inoculated into LB medium and grown overnight, then diluted 1:10 the following morning and grown at 37°C until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached. The induction was performed using 1 mM IPTG at 37°C for 3 h. After harvesting, cells were lysed by sonication and the insoluble material removed by centrifugation at 25,000g for 40 min. The supernatant was applied on a Ni2+-NTA agarose column (Qiagen), the eluted material dialyzed, and further purified on a Q-Sepharose fast flow matrix (GE Healthcare) as previously described (Cencic et al. 2007).

RNA helicase assays

Helicase activity was assessed using [32P]-labeled RNA probe (RNA-1/RNA-11 duplex) and eIF4A1 (0.56 µM) or Ded1p (0.5 µM), essentially as previously described (Rogers et al. 1999). In short, the reaction was prepared by the addition of 2 µM [32P]-labeled duplex in 1× helicase buffer [20 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.5), 70 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM Mg(OAc)2], 20 µg of acetylated BSA (Ambion), and 1 mM ATP. Reactions were incubated at 35°C for 15 min and stopped by the addition of 1× Stop Solution (10% glycerol, 0.2% SDS, 2 mM EDTA). Reaction components were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel (29:1; acrylamide/bisacrylamide), dried and quantitated using the Typhoon Trio Imager (GE Healthcare). Gels were also exposed to film (Kodak X-Omat).

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed in PBS and lysed in protease inhibitor-enriched RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA,1 mM EGTA, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 4 μg/mL aprotinin, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 2 μg/mL pepstatin). Proteins were resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). Antibodies against p-eIF2α (Ser51), total eIF2α, and eEF2 (#9721, #5353, and #2332, respectively) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Tyler Fulton, Carina Jette, and Dr. Brian Stoltz (Caltech) for their generous gift of elatol. This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148366) to J.P.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.072884.119.

REFERENCES

- Abdelkrim YZ, Harigua-Souiai E, Barhoumi M, Banroques J, Blondel A, Guizani I, Tanner NK. 2018. The steroid derivative 6-aminocholestanol inhibits the DEAD-box helicase eIF4A (LieIF4A) from the Trypanosomatid parasite Leishmania by perturbing the RNA and ATP binding sites. Mol Biochem Parasitol 226: 9–19. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell JB, Holloway GA. 2010. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J Med Chem 53: 2719–2740. 10.1021/jm901137j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo PH, Wan KF, Sivaraman T, Xu J, Moore FK, Hung AW, Mok HY, Yu VC, Chai CL. 2008. Structure-activity relationship studies of phenanthridine-based Bcl-XL inhibitors. J Med Chem 51: 6699–6710. 10.1021/jm8005433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat M, Robichaud N, Hulea L, Sonenberg N, Pelletier J, Topisirovic I. 2015. Targeting the translation machinery in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14: 261–278. 10.1038/nrd4505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeleau ME, Matthews J, Wojnar JM, Lindqvist L, Novac O, Jankowsky E, Sonenberg N, Northcote P, Teesdale-Spittle P, Pelletier J. 2005. Stimulation of mammalian translation initiation factor eIF4A activity by a small molecule inhibitor of eukaryotic translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 10460–10465. 10.1073/pnas.0504249102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeleau ME, Mori A, Oberer M, Lindqvist L, Chard LS, Higa T, Belsham GJ, Wagner G, Tanaka J, Pelletier J. 2006. Functional characterization of IRESes by an inhibitor of the RNA helicase eIF4A. Nat Chem Biol 2: 213–220. 10.1038/nchembio776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeleau ME, Robert F, Gerard B, Lindqvist L, Chen SM, Wendel HG, Brem B, Greger H, Lowe SW, Porco JA, et al. 2008. Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation modulates chemosensitivity in a mouse lymphoma model. J Clin Invest 118: 2651–2660. 10.1172/JCI34753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornhorst JA, Falke JJ. 2000. Purification of proteins using polyhistidine affinity tags. Methods Enzymol 326: 245–254. 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)26058-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cencic R, Robert F, Pelletier J. 2007. Identifying small molecule inhibitors of eukaryotic translation initiation. Methods Enzymol 431: 269–302. 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31013-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cencic R, Carrier M, Galicia-Vázquez G, Bordeleau ME, Sukarieh R, Bourdeau A, Brem B, Teodoro JG, Greger H, Tremblay ML, et al. 2009. Antitumor activity and mechanism of action of the cyclopenta[b]benzofuran, silvestrol. PLoS ONE 4: e5223 10.1371/journal.pone.0005223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cencic R, Galicia-Vázquez G, Pelletier J. 2012. Inhibitors of translation targeting eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A. Methods Enzymol 511: 437–461. 10.1016/B978-0-12-396546-2.00020-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cencic R, Robert F, Galicia-Vázquez G, Malina A, Ravindar K, Somaiah R, Pierre P, Tanaka J, Deslongchamps P, Pelletier J. 2013. Modifying chemotherapy response by targeted inhibition of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A. Blood Cancer J 3: e128 10.1038/bcj.2013.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi MM, Kumar A, Darnay BG, Chainy GB, Agarwal S, Aggarwal BB. 1997. Sanguinarine (pseudochelerythrine) is a potent inhibitor of NF-κB activation, IκBα phosphorylation, and degradation. J Biol Chem 272: 30129–30134. 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Pelletier J. 2015. Targeting the eIF4A RNA helicase as an anti-neoplastic approach. Biochim Biophys Acta 1849: 781–791. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Galicia-Vázquez G, Cencic R, Mills JR, Katigbak A, Porco JA Jr, Pelletier J. 2016. CRISPR-mediated drug-target validation reveals selective pharmacological inhibition of the RNA helicase, eIF4A. Cell Rep 15: 2340–2347. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CS, Doudna JA. 2007. Structural and mechanistic insights into hepatitis C viral translation initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 29–38. 10.1038/nrmicro1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galadari S, Rahman A, Pallichankandy S, Thayyullathil F. 2017. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of sanguinarine—a benzophenanthridine alkaloid. Phytomedicine 34: 143–153. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galicia-Vázquez G, Chu J, Pelletier J. 2015. eIF4AII is dispensable for miRNA-mediated gene silencing. RNA 21: 1826–1833. 10.1261/rna.052225.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Pradhan SK, Kar A, Chowdhury S, Dasgupta D. 2013. Molecular basis of recognition of quadruplexes human telomere and c-myc promoter by the putative anticancer agent sanguinarine. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830: 4189–4201. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JR, Konicek BW, Vincent TM, Lynch RL, Monteith D, Weir SN, Schwier P, Capen A, Goode RL, Dowless MS, et al. 2007. Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation factor eIF4E expression reduces tumor growth without toxicity. J Clin Invest 117: 2638–2648. 10.1172/JCI32044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144: 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harigua-Souiai E, Abdelkrim YZ, Bassoumi-Jamoussi I, Zakraoui O, Bouvier G, Essafi-Benkhadir K, Banroques J, Desdouits N, Munier-Lehmann H, Barhoumi M, et al. 2018. Identification of novel leishmanicidal molecules by virtual and biochemical screenings targeting Leishmania eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006160 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Floor SN, Ingolia NT. 2016. Rocaglates convert DEAD-box protein eIF4A into a sequence-selective translational repressor. Nature 534: 558–561. 10.1038/nature17978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Iwasaki W, Takahashi M, Sakamoto A, Watanabe C, Shichino Y, Floor SN, Fujiwara K, Mito M, Dodo K, et al. 2019. The translation inhibitor rocaglamide targets a bimolecular cavity between eIF4A and polypurine RNA. Mol Cell 73: 738–748 e739. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Tang W, Ding L, Tan R, Li X, Lu L, Jiang J, Cui Z, Tang Z, Li W, et al. 2019. Targeting the N terminus of eIF4AI for inhibition of its catalytic recycling. Cell Chem Biol 26: 1417–1426.e5. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WJ, Kim JH, Jang SK. 2007. Anti-inflammatory lipid mediator 15d-PGJ2 inhibits translation through inactivation of eIF4A. EMBO J 26: 5020–5032. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov G, Xu Q, Rudolph-Owen L, Tendyke K, Liu J, Towle M, Zhao N, Marsh J, Agoulnik S, Twine N, et al. 2009. Potent in vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of des-methyl, des-amino pateamine A, a synthetic analogue of marine natural product pateamine A. Mol Cancer Ther 8: 1250–1260. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaris-Karatzas A, Montine KS, Sonenberg N. 1990. Malignant transformation by a eukaryotic initiation factor subunit that binds to mRNA 5′ cap. Nature 345: 544–547. 10.1038/345544a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Cencic R, Mills JR, Robert F, Pelletier J. 2008. c-Myc and eIF4F are components of a feedforward loop that links transcription and translation. Cancer Res 68: 5326–5334. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Nasr Z, Premsrirut PK, Porco JA Jr, Hippo Y, Lowe SW, Pelletier J. 2012. Targeting synthetic lethal interactions between Myc and the eIF4F complex impedes tumorigenesis. Cell Rep 1: 325–333. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist L, Oberer M, Reibarkh M, Cencic R, Bordeleau ME, Vogt E, Marintchev A, Tanaka J, Fagotto F, Altmann M, et al. 2008. Selective pharmacological targeting of a DEAD box RNA helicase. PLoS ONE 3: e1583 10.1371/journal.pone.0001583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorsch JR, Herschlag D. 1998. The DEAD box protein eIF4A. 1. A minimal kinetic and thermodynamic framework reveals coupled binding of RNA and nucleotide. Biochemistry 37: 2180–2193. 10.1021/bi972430g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low WK, Dang Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, Shi Z, Choi NS, Merrick WC, Romo D, Liu JO. 2005. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation by the marine natural product pateamine A. Mol Cell 20: 709–722. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcone S, Fitzgerald DJ. 2013. Proteomic identification of the candidate target proteins of 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2. Proteomics 13: 2135–2139. 10.1002/pmic.201200289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milojevic T, Sonnleitner E, Romeo A, Djinović-Carugo K, Bläsi U. 2013. False positive RNA binding activities after Ni-affinity purification from Escherichia coli. RNA Biol 10: 1066–1069. 10.4161/rna.25195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Fleming T, Kadiyska I, Brings S, Groener JB, Nawroth P, Hecker M, Brune M. 2018. Sensitive mass spectrometric assay for determination of 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 and its application in human plasma samples of patients with diabetes. Anal Bioanal Chem 410: 521–528. 10.1007/s00216-017-0748-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen PJ, Trachsel H. 1988. The mouse protein synthesis initiation factor 4A gene family includes two related functional genes which are differentially expressed. EMBO J 7: 2097–2105. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novac O, Guenier AS, Pelletier J. 2004. Inhibitors of protein synthesis identified by a high throughput multiplexed translation screen. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 902–915. 10.1093/nar/gkh235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakos-Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, Gorman AM. 2016. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep 17: 1374–1395. 10.15252/embr.201642195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters TL, Tillotson J, Yeomans AM, Wilmore S, Lemm E, Jiménez-Romero C, Amador LA, Li L, Amin AD, Pongtornpipat P, et al. 2018. Target-based screening against eIF4A1 reveals the marine natural product elatol as a novel inhibitor of translation initiation with in vivo antitumor activity. Clin Cancer Res 24: 4256–4270. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourdehnad M, Truitt ML, Siddiqi IN, Ducker GS, Shokat KM, Ruggero D. 2013. Myc and mTOR converge on a common node in protein synthesis control that confers synthetic lethality in Myc-driven cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 11988–11993. 10.1073/pnas.1310230110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert F, Roman W, Bramoullé A, Fellmann C, Roulston A, Shustik C, Porco JA Jr, Shore GC, Sebag M, Pelletier J. 2014. Translation initiation factor eIF4F modifies the dexamethasone response in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 13421–13426. 10.1073/pnas.1402650111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez AD, Ramírez C, Rodríguez II. 1999. Elisabatins A and B: new amphilectane-type diterpenes from the West Indian sea whip Pseudopterogorgia elisabethae. J Nat Prod 62: 997–999. 10.1021/np990090p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers GW Jr, Richter NJ, Merrick WC. 1999. Biochemical and kinetic characterization of the RNA helicase activity of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A. J Biol Chem 274: 12236–12244. 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen F, Edery I, Meerovitch K, Dever TE, Merrick WC, Sonenberg N. 1990. Bidirectional RNA helicase activity of eucaryotic translation initiation factors 4A and 4F. Mol Cell Biol 10: 1134–1144. 10.1128/MCB.10.3.1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero D, Montanaro L, Ma L, Xu W, Londei P, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. 2004. The translation factor eIF-4E promotes tumor formation and cooperates with c-Myc in lymphomagenesis. Nat Med 10: 484–486. 10.1038/nm1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somaiah R, Ravindar K, Cencic R, Pelletier J, Deslongchamps P. 2014. Synthesis of the antiproliferative agent hippuristanol and its analogues from hydrocortisone via Hg(II)-catalyzed spiroketalization: structure–activity relationship. J Med Chem 57: 2511–2523. 10.1021/jm401799j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers JA, Kulikowicz T, Croteau DL, Dexheimer T, Dorjsuren D, Jadhav A, Maloney DJ, Simeonov A, Bohr VA, Brosh RM Jr. 2019. A high-throughput screen to identify novel small molecule inhibitors of the Werner Syndrome Helicase-Nuclease (WRN). PLoS One 14: e0210525 10.1371/journal.pone.0210525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Liu C, Nadiminty N, Lou W, Zhu Y, Yang J, Evans CP, Zhou Q, Gao AC. 2012. Inhibition of Stat3 activation by sanguinarine suppresses prostate cancer cell growth and invasion. Prostate 72: 82–89. 10.1002/pros.21409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Atas E, Lindqvist LM, Sonenberg N, Pelletier J, Meller A. 2014. Single-molecule kinetics of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4AI upon RNA unwinding. Structure 22: 941–948. 10.1016/j.str.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillotson J, Kedzior M, Guimarães L, Ross AB, Peters TL, Ambrose AJ, Schmidlin CJ, Zhang DD, Costa-Lotufo LV, Rodríguez AD, et al. 2017. ATP-competitive, marine derived natural products that target the DEAD box helicase, eIF4A. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 27: 4082–4085. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.07.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt A, Tamewitz A, Skoko J, Sikorski RP, Giuliano KA, Lazo JS. 2005. The benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloid, sanguinarine, is a selective, cell-active inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. J Biol Chem 280: 19078–19086. 10.1074/jbc.M501467200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel HG, De Stanchina E, Fridman JS, Malina A, Ray S, Kogan S, Cordon-Cardo C, Pelletier J, Lowe SW. 2004. Survival signalling by Akt and eIF4E in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nature 428: 332–337. 10.1038/nature02369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DE, Stewart IC, Grubbs RH, Stoltz BM. 2008. The catalytic asymmetric total synthesis of elatol. J Am Chem Soc 130: 810–811. 10.1021/ja710294k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder-Hill J, Pause A, Sonenberg N, Merrick WC. 1993. The p46 subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)-4F exchanges with eIF-4A. J Biol Chem 268: 5566–5573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun SJ, Kim H, Jung SH, Kim JH, Ryu JE, Singh NJ, Jeon J, Han JK, Kim CH, Kim S, et al. 2018. The mechanistic insight of a specific interaction between 15d-Prostaglandin-J2 and eIF4A suggests an evolutionary conserved role across species. Biol Open 7: bio035402 10.1242/bio.035402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeder-Lutz G, Choulier L, Besse M, Cousido-Siah A, Ruiz Figueras FX, Didier B, Jung ML, Podjarny A, Altschuh D. 2012. Validation of surface plasmon resonance screening of a diverse chemical library for the discovery of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b binders. Anal Biochem 421: 417–427. 10.1016/j.ab.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.