Abstract

Cooperation and harmonisation of standards in the pharmaceutical domain is already a reality and, in fact, has been increasingly important in recent decades. This harmonisation seems natural and logical in the current environment of increased globalisation imposed by the current geo-economic-political situation. However, even though this is a reality, it is important to analyse whether or not all stakeholders benefit from this increased cooperation and harmonisation, in order to recommend future actions or potential improvements.

Cooperation, convergence and harmonisation is indeed not an end in itself. Elimination of differences, agreement on common standards and the increase of cooperation are needed to protect and promote global public health. It is therefore very important to thoroughly analyse the value and impact of the harmonisation and cooperation process, and to determine whether or not all the efforts made throughout the years have indeed met expectations. After many years of experience, it seems important to have a thorough evaluation to answer several important questions:

-

▸

What has been the benefit of the multiple harmonisation and cooperation initiatives so far?

-

▸

Should such processes continue? Are there any other alternatives to resolve current challenges?

-

▸

Should current initiatives and projects be improved? If so, how and what are the priorities?

-

▸

Would greater harmonisation and closer cooperation be beneficial? Is it possible? Is it necessary? What are the limits of this process?

-

▸

What are the important lessons from the past and the on-going harmonisation initiatives that should be considered for planning the next steps?

This book section’s goal is to answer these important questions by thoroughly evaluating the added value of cooperation, convergence and harmonisation. This book section also reviews the critical parameters and influencing factors for cooperation, convergence and harmonisation. This review/analysis of critical parameters and influencing factors is essential to understand the complexity of the situation and effectively discuss how to organise the next steps of global cooperation.

Keywords: Globalisation, Regulation, Medicine, Cooperation, Convergence, Harmonisation, International, Regional, Bilateral, Network, Pharmaceutical, Standard, Requirement, Best Practice, Regulatory capacity, resources, expertise, infrastructure, Communication, Planning, Organisation, Structure, Implementation, monitoring, Voluntary cooperation, Legal commitment, Influence, Politics, Political decisions, Economy, Cultures, Traditions, Ethnic Factors, Medical practices, legislations, Statutes, regulatory systems, cost effectiveness

Following the review of all major harmonization initiatives in the pharmaceutical sector (see Part I), two questions need to be answered before any action can be recommended:

-

▸

Do the ongoing and past harmonization initiatives have (or have they had) value, and if so, would further harmonization be possible and would it be beneficial?

-

▸

What are the important lessons from the past, and the ongoing harmonization initiatives that should be considered for planning the next steps?

II-1). Value of the Cooperation, Convergence, and Harmonization in the Pharmaceutical Domain

Differences in regulations between countries have been a problem in many areas (i.e., mobile phones, electrical equipment, etc.). In past decades, these differences were more problematic, but today it is common to travel and to buy and sell items on the Internet between people living throughout the world. To support this globalization of economic and social expectations, the harmonization of standards and regulations is necessary in many areas. Therefore, competent authorities began to collaborate, most of the time under the United Nations (UN) organization, to exchange information and to harmonize their regulations. These collaborations have been successful in certain domains (e.g., international air navigation), while challenging in others (e.g., climate change).

Cooperation and harmonization of standards in the pharmaceutical domain are already a reality, and have in fact been increasingly important in the past several decades (see Part I). This harmonization seems natural and logical in the current environment of increased globalization imposed by the current geo-economic-political situation. However, even though this is a reality, it is important to analyze whether all stakeholders benefit from this increased cooperation and harmonization in order to recommend future actions or potential improvements.

II-1.1). Value for Patients and Global Public Health

Even though there are differences between developed and developing countries or between regions, diseases go beyond borders and are present worldwide. It therefore seems logical that the development and manufacture of medicines against these diseases should be based on the same global standards, independent of where the sites of manufacture are or the clinical studies occur.

The harmonization of standards and cooperation between countries are beneficial to patients and global public health in several ways:

-

▸

Increase of Worldwide Access to Medicines: Pharmaceutical access is defined as the timely availability of quality medicines to those patients who need them. The unavailability of some medicines poses a real threat to public health and welfare. Many interrelated factors (i.e., availability of financial resources, government policies, infrastructure conditions, private and public sector insurance programs, appropriate use, supply management, manufacturing capacity, research and development decisions, etc.) determine the level of access. It is clear that the level of harmonization of pharmaceutical regulations and cooperation (regionally or globally) also influences pharmaceutical access in both developed and developing countries. These activities increase the availability of high-quality, safe, and effective medicines worldwide, and promote better access to a larger worldwide population. For example, the “drug lag” in Japan (i.e., delay of availability of new medicines vs. the US) has been partly attributed to specific local requirements requested by Japanese regulators. The same analysis partly attributed the recent reduction of this “drug lag” (from 2.4 years in 2006 to 1.1 years in 2010) to the implementation of PMDA measures to increase global cooperation [280].

By promoting the conduct of multinational clinical trials that meet international standards, the harmonization of regulation also facilitates faster access to innovative and quality medicines for worldwide patients. Indeed, harmonization of rules (i.e., implementation of ICH Good Clinical Practices [GCP]) and the introduction of a “mature” regulatory system (i.e., consistent and transparent) increase the interest of the global pharmaceutical industry in performing multinational studies, and therefore increase access to drugs in development for patients from these countries.

-

▸

Promotion of the Development and Implementation of High Standards: Collaboration facilitates dissemination, recognition, and adoption of best practices. Moreover, if the creation/harmonization of an international standard follows an appropriate and rigorous process (i.e., based on scientifically driven discussions), the quality, robustness, and relevance of such standards will increase as it integrates different expertise, experiences, and points of view from the best worldwide experts in the field. This will ultimately benefit the patients who will have the assurance that their medicines have been developed and manufactured according to the highest standards.

In certain domains, there are a limited number of experts worldwide (e.g., new technologies or specific diseases), therefore it is critical to gather these international experts together to develop high-quality standards.

-

▸

Reduction of Unnecessary Testing in Animals and Humans: The reduction of unnecessary testing in animals and humans should always be a priority for ethical reasons. The amount of human and animal experimentation is reduced when companies only have to produce one set of data for all regions.

-

▸

Promotion of Innovation and Development of Medicines for Unmet Medical Needs: One could question if the increase in harmonization of standards can decrease innovation and delay availability of a drug in certain markets. For example, it could be argued that if today Country A requires a one-year study to support the registration of a new product in a specific indication, while Country B requires only six months, the harmonization of requirements could potentially delay the availability of this product in Country B by six months. However, although there is indeed a risk of delay, which may in fact be beneficial for the patient if the harmonization discussions conclude that the risk/benefit assessment is more relevant at 12 months, harmonization and cooperation activities are in fact contributing to pharmaceutical innovation by promoting predictable and consistent requirements [281] and reducing regulatory uncertainty. Reducing the risk for industry (by releasing clear and harmonized technical guidelines and accepting foreign data), and increasing return on investment (by increasing global marketing opportunities), these harmonization activities stimulate investment in research and development (R&D). Moreover, the elimination of redundancy and duplication of work and testing to satisfy different requirements frees up resources for R&D. Finally, MedDRA and other harmonization of terminologies facilitate and increase communication between experts, which in turn increases cooperation and innovation.

Harmonization of regulations and requirements can also make development of certain types of products financially viable for industry. These development projects would indeed not be funded if different worldwide requirements needed different programs or clinical studies to support global registration. For example, before ICH recommendations on how to demonstrate comparability of biotechnological/biological products subject to changes in their manufacturing process [282], regional disparities created economic problems (i.e., wasted inventories, shelf-life, several parallel manufacturing processes) or implementation delays for industry, which discouraged process upgrades and improvements.

Finally, it is also important to note that harmonization of requirements is critical for the development and availability of orphan drugs that treat life-threatening conditions and rare diseases because it allows multinational clinical studies and obviates the development challenges due to the limited number of patients. The success of the European Union (EU) orphan drug regulation demonstrated how harmonization and cooperation can improve public health and increase availability of these types of medicines. Prior to this European legislation, a number of Member States had adopted specific measures to increase knowledge on rare diseases, but these initiatives did not lead to any significant progress in research on rare diseases. Following the implementation of EU Regulation (EC) No 141/2000, the number of orphan medicinal products authorized significantly increased. During the first five years of the implementation, 458 applications for orphan designation were submitted, resulting in 268 products being designated, relating to over 200 different rare conditions [283].

-

▸

Contribution to the Control of Medicine Quality: The harmonization of technical quality standards (e.g., Good Manufacturing Practices [GMP] domain) contributes to ensure that medicines, most of the time developed, manufactured, and tested in different countries, are of good quality.

Moreover, falsified medicines are a major threat to public health and safety. As falsifications become more sophisticated, the risk that falsified medicines reach patients in undeveloped (as well as developed) countries increases every year. This calls for a comprehensive strategy at the international level. International cooperation already exists through the International Medical Products Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce (IMPACT) [284] created by WHO in 2006. International cooperation and harmonization of regulatory actions are critical to ensure success against falsified medicines.

-

▸

Contribution to the Evaluation and Monitoring of the Safety of Medicines: The establishment of a global collaboration framework and the harmonization of reporting (i.e., formats and processes) enhance the safety of products. It allows exchange of information and rapid communications between worldwide DRAs regarding new product safety problems via agreed-upon common tools (e.g., Electronic Individual Case Safety Reports, Periodic Safety Update Report [PSUR], and Development Safety Update Report [DSUR]). This is critical to better monitor the safety of medicines, and has a direct benefit for patients.

Such cooperation also allows pooling of information from different sources, regions, and countries. This increase of the quantity of safety information facilitates the early detection of possible safety signals and therefore improves the monitoring of product safety.

Pharmacovigilance would be even more effective if it was supported by a truly effective “global” system. Pharmaceutical companies already have global departments that assess the safety profile of a product based on safety reporting from different parts of the world where the product is registered and marketed. True harmonization of practices and cooperation between worldwide DRAs is also necessary to have a real safety profile of the product (especially for an orphan drug where the patient population is limited).

-

▸

Support to Developing Countries: Global cooperation and harmonization of standards support and assist achievement of the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) as discussed in Part I-1.1. These activities improve health in developing regions by increasing access to safe and effective medicines of good quality. This is accomplished by strengthening the technical and administrative capacity via collaboration and the sharing of resources and expertise [285].

Technical and administrative assistance from the international community (i.e., ICH, WHO, or major DRAs) are indeed critical in supporting the development and enhancement of regulation in certain regions (e.g., Africa). This assistance (i.e., training, development of high quality standards, and technology transfer) helps developing countries to establish a mature regulatory system. It provides mentoring opportunities where more experienced DRAs from developed countries can share knowledge and experience with less advanced DRAs from developing countries. Without the help from international organizations, these countries/regions would not have the resources, expertise, or time to discuss, assess, and regulate new topics (i.e., biosimilars, gene therapies, etc.). If they apply “standard” rules to these types of state-of-the-art products and therapy, the patients may be exposed to risk.

Harmonization and cooperation also facilitate the economic development of low-income countries because they increase the attractiveness of their local facilities for the manufacture of medicines and the conduct of clinical studies. A 2010 Industry Survey [286] showed that better cooperation between African countries (to reduce country-specific requirements) would promote access to new medicines, encourage more companies to register medicines in Africa, and ensure a continuous supply of medicines. Indeed, specific country requirements increase the cost of medicines to African countries, and in some cases contribute to the discontinuation of medical supplies to these countries.

Finally, until recently, the focus of DRAs from developing countries was to exercise a regulatory oversight on products that were licensed and used in developed countries. However, some new products (i.e., new vaccines) are now being developed for use in the developing world, and sometimes exclusively in these markets. More clinical trials are being conducted in countries with weak regulatory systems, who are therefore confronted with new challenges which they are not in a position to address (i.e., assessing clinical trial applications and marketing applications not yet assessed by a developed country) [287]. Several initiatives, such as the WHO prequalification of products, the WHO regulatory pathways initiative, the WHO Initiative for Vaccine Research, or the EMA Scientific Opinion via the “Article 58” procedure, have already been established. International cooperation between WHO, developed countries, and developing countries is critical in this situation.

All the above benefits of harmonization and cooperation to patients and global public health are even more apparent if one reviews the public health risks that the lack of harmonization would generate. For example, in the absence of the ICH process, the DRAs of the three ICH regions may have continued to diverge in their practice and may have requested further local/regional focus and repetition in drug development activities. This increase of development time and efforts would have surely delayed the availability of key medicines to patients. Moreover, if there were no cooperation and harmonization, certain developing countries would not be able to develop and implement functioning regulatory systems and pharmaceutical regulation on their own. This lack of pharmaceutical control would alleviate unethical activities that would ultimately impact global public health with:

-

▸

Increased production and importation of substandard/counterfeit medicines [288]

-

▸

Conduct of unethical clinical trials

-

▸

Corruption

-

▸

Distribution of unregistered medicines

-

▸

Irrational prescribing practice

-

▸

Irrational dispensing practice

The case of biosimilar products also demonstrates how the lack of harmonized requirements (or lack of implementation of harmonized standards) can impact public health. Although these products have recently been an important global health topic of discussion and many countries prepared appropriate requirements over the past several years, other countries have not yet developed specific regulations (or not yet integrated the WHO recommendations) to cover the risk associated with the approval and use of these specific products. Due to the lack of appropriate regulation related to this specific type of product (and sometimes without having any regulations for biologics at all), these countries (i.e., Argentina) evaluate and approve these “biosimilar” products using the same requirements as those for standard generics. They do not take into consideration the specific risks associated with biosimilar products [289] not present in the case of standard generic (e.g., immunogenicity). In some countries, the need for less expensive medicines may also link to the approval of subpotent biological/biosimilar products. This lack of implementation of international requirements and standards has an obvious risk for patients and public health.

II-1.2). Value for Regulators

DRAs have the mandate to protect and enhance the health of their population by facilitating access to medicines of public health importance without compromising on quality, safety, and efficacy. However, as international markets expand and pharmaceutical companies operate more and more globally, the task of regulators to assess compliance with legislation and monitor the safety and quality of medicines becomes increasingly difficult and resource intensive. In addition, cuts in government budgets in recent years oblige the DRAs to rethink processes and utilization of resources. This is obviously a difficult exercise because they need to manage new challenges (i.e., increased globalization but also sophisticated products, new technologies, increased communication through the Internet, counterfeiting, etc.) with less budget and resources. In this context, maintaining the capacity and expertise to meet their obligations becomes a problem. As rightly stated by the Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community in the Nassau Declaration on Health in July 2001, “while the resources and absorptive capacity of no one single institution, country or nation are sufficient to reverse the negative trend, the evidence of ‘best practices’ and technological breakthroughs, the international, regional and national mechanisms and frameworks … provide hope of what can be achieved through a collective response” [290].

Cooperation with other countries seems indeed the only alternative to manage the situation and to address the specific challenges associated with the globalization of the development, manufacture, and distribution of medicines. This is not a choice anymore if these countries want to provide people with more effective and safer medicines more quickly [291]. Therefore, cooperation has been intensified at different levels and the networking of institutions in developing and developed countries is an important element in building regulatory capacity and trust. Development of common standards for scientific evaluation and inspection also facilitates regulatory communication and information sharing. Of course, each country will remain responsible for the final decision (e.g., to approve/suspend a drug), but exchange of evaluation/information (e.g., safety alerts) is a “must” and not a “nice to have” anymore. Worldwide DRAs are required to harmonize their activities with the international community. Numerous Memorandum of Agreements (MoA) or Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) have been put in place between DRAs to allow legal exchange of information.

However, even if this has been imposed on them, most regulators now agree that domestic and international measures complement each other, and therefore domestic and international operations should be carried out seamlessly with the understanding that they are inseparable in nature [292]. For example, the new international focus of the US FDA and the reorganization of its inspectional resources (i.e., the opening of overseas offices) helped to enforce compliance, and it is now easier for the US FDA to control and inspect these foreign manufacturing sites [293]. The ICH process also demonstrated that harmonization brings value and benefits to DRAs because it improves consistency, efficiency, and transparency of review, which in turn facilitates information sharing among regulators and ultimately promotes faster access to life-saving treatments to patients on a worldwide basis [294].

Moreover, harmonization and cooperation also allow regulators to learn from each other’s experiences, to leverage international expertise, and to keep up with international best practices and standards. For example, the decision by the EMA and US FDA to collaborate on biosimilar products will certainly help the US FDA to catch up with Europe in its development of the regulation of these products. Indeed, Europe has already gathered a lot of experience in this area (the first biosimilar product was approved in Europe in 2006), while the US has just recently passed their law on biosimilars. In Europe the regulatory framework for biosimilars is largely established, with both general guidelines and product-specific guidelines (e.g., human insulin, somatropin, erythropoietins, interferon-alpha, low-molecular-weight heparins, and monoclonal antibodies) having been put in place by the EMA. The EMA is also currently working on draft guidelines for a number of other product class-specific guidelines, including interferon-beta and follicle-stimulation hormone. The US, on the other hand, is lagging behind the EU because the legal pathway (Biologics Price Competition and Innovation [BPCI] Act) was only signed into law on March 23, 2010 by US President Barack Obama [295].

DRAs from developing countries also benefit from the experience, expertise, and resources from other countries. Regulators from these developing countries also see the value in cooperating with both developed and developing countries [296]. For instance, the cooperation project between Brazil and Mozambique demonstrates that cooperation and harmonization between developing countries can be very beneficial [297].

Finally, harmonization also decreases the duplication of activities and therefore facilitates work sharing and optimization of DRAs’ time and resources. It can help manage DRAs’ workloads more efficiently (critical due to the increase of complex and voluminous data to review in a resource-constrained environment), and ultimately improve overall regulatory performance. It is also a way to resolve some of the resource limitations and budget constraints in developing countries. However, although important, resource saving should not be the only objective to ensure success of cooperation. Even if it is expected that cooperation and harmonization can increase efficiency in the long term, such activities can in fact require more work at the beginning. Harmonization and cooperation can deliver much more than resource saving (e.g., better informed decisions, increased protection of public health, and facilitated availability of medicines in developing countries).

Even if the vast majority of worldwide regulators and national DRAs fully support and recognize the value of harmonization and cooperation, some resistance may sometimes arise. This sporadic resistance from some regulators and national authorities to increase cooperation and harmonization is inherent to the relative fear of losing “power” and sovereignty. These concerns need to be kept in mind when establishing new harmonization projects or collaboration as it could raise implementation challenges, even if this threat is not fully realized. Indeed, even if cooperation obviously implies recognition of other evaluations and expertise, regional or global cooperation does not replace national judgment/decisions and harmonization does not automatically mean a loss of national sovereignty or autonomy. It depends on the model selected (i.e., integration vs. cooperation) and the stage of the harmonization process. Collaborative mechanisms (i.e., joint assessments or inspections) does not imply common decision making. Close collaboration can occur even if a registration decision itself stays in the hands of sovereign nations. The European system also demonstrates that, even in a case of integration where Member States relinquished part of their sovereignty in favor of the Community and delegated some of their decision-making powers to shared institutions and supranational bodies, national DRAs remained crucial for the pharmaceutical network. For example, experts and regulators involved in harmonization activities come from national DRAs (i.e., EMA is a network of experts who are made available by the national DRAs of all EU Member States).

Regional and global collaboration does not replace national DRAs. This is an evolution of regulators’ activities and responsibilities. National DRAs will still be responsible for managing specific countries’ health needs and establishing public health priorities. Even if a global medicines evaluation system were established, national DRAs would remain the ultimate decision-making bodies. However, everyone can learn something from others! To fulfill their mandate to promote and protect public health in the current global environment, each DRA needs to ask itself the following questions:

-

▸

What are the strengths of counterpart DRAs?

-

▸

How do we leverage each other competencies and expertise?

II-1.3). Value for Industry

The cost of drug development increased considerably in the past decade due to more advanced and expensive technology and new requirements. Today, the average cost of bringing a new medicine to market is US $1.3 billion [298], it takes approximately 12 years (from the first toxicity dose to the first launch), and it has a success rate of 5% [299]. The combination of this strong increase in research and development (R&D) costs and the decrease of new molecular entity (NME) approvals has significantly impacted R&D productivity. Moreover, reduction in prices and reimbursement of medicines by worldwide governments (due to health budget restrictions), combined with low sales growth, has placed additional pressure on profit margins for pharmaceutical companies [300]. The only solution for innovative companies to keep up with this decrease of R&D productivity and to improve their return on investment is to market new medicines globally with minimal additional costs required to satisfy the regulatory requirements of different countries.

However, although entering global markets has significant advantages and facilitates return on investment, pharmaceutical companies face challenges in marketing their products in different countries/regions with diverse regulatory requirements and practices. These different, and sometimes conflicting or contradictory, requirements make this global effort difficult, time consuming, and costly. Pharmaceutical companies must integrate the challenge of complying with these disparate international requirements and regulatory systems. This means expending resources to develop knowledge on local specificities and markets that translate to operational complexity and additional costs and time. Resources that could best be used for increasing R&D productivity are often used to meet different regulatory requirements that may add little to the evaluation of the risk–benefit of new therapies. More importantly, these specific local requirements delay the availability of new medicines for the population of these countries.

It is of course essential to establish a sufficient body of clinical and scientific evidence to ensure that newly introduced innovative medicines are safe and effective. This work is needed whatever the cost and resources it requires. However, some of the existing local regulatory requirements that necessitate repetition of work already conducted are viewed as impeding the ability to rapidly bring innovative medicines to address unmet medical needs. Indeed, this regulatory variability across multiple countries brings an extreme complexity to development activities and ultimately impedes, rather than facilitates, patient access to meaningful, new, evidence-based medicines [301]. On the contrary, consistency and scientific quality of recommendations from DRAs (e.g., for study design) ease the development of new medicines and reduce the risk.

The ICH process demonstrated that harmonization brings value and benefits to pharmaceutical industries as it enables industry to reduce development times by removing the duplication of studies that was previously required to gain global market approval for a new medicine. This directly affects the bottom line through reduced development times and resources (that can be allocated to new additional development projects). This harmonization of standards also facilitates organization of companies and intracompany globalization [302].

Harmonization of quality specifications and analytical tests between countries would also mean an important cost savings for industry. It would reduce the need for several tests and batch releases of the same product batch. Moreover, some countries require in-country testing of each lot marketed in their territory (these analytical tests are performed by a government laboratory or a third-party laboratory contracted by the DRAs). If all countries had the same specifications and tests, and agreed to accept analytical results from other countries, in-country testing would not need to be repeated in several countries. This elimination of duplication of testing would obviously reduce the cost, time, and resources associated with multiple lot releases and in-country testing. This is also important for in vivo assays, to reduce unnecessary use of animals.

Harmonization of requirements also facilitates the development of new markets that are currently not profitable for global companies due to the cost of specific requirements. However, it is important to ensure that global standards are appropriately implemented in each region/country to avoid disadvantaging local drug manufacturers/industries. The implementation of global standards should not create a barrier to local companies and facilitate big global industry. It is therefore important to balance the necessary implementation of scientific global standards to support/improve public health in all countries while addressing the needs of each country. Overregulating the pharmaceutical market in low-income countries could indeed impact the local economy.

Some industry representatives may at first be opposed to the harmonization of regulation for several reasons. The first concern from industry is the unnecessary increase of requirements that harmonization and cooperation could generate. This is a legitimate concern because an easy way to harmonize a topic between countries is to combine all current requirements from different countries (i.e., if one country requests Study A and another country requests Study B for the registration of new medicines, a quick solution would be to ask for both Studies A and B). To avoid this unreasonable duplication of requirements (which would be against one of the main objectives of harmonization: to reduce duplication of activities), the harmonization process needs to be considered carefully. This harmonization needs to be based on scientific evidence and evaluation to allow for the development of high standards. This is not a quick compromise or addition of requirements, but a common requirement established following a thorough evaluation of the situation. Of course, the basis of this common scientific evaluation needs to take into account the existing worldwide requirements. The ICH process is an excellent example of how scientific-driven evaluation can produce common high-quality standards.

Second, one could argue that these new global requirements could reduce flexibility and a creative “development program.” They are also concerned that harmonization may impact regulator and sponsor interaction during the development of medicines and that certain regulators may apply these new harmonized rules to everyone without discerning the specificity of each product/program. Although these concerns need to be kept in mind when organizing and implementing the next steps of global harmonization and cooperation, they seem to be not fully relevant for the following reasons:

-

▸

For nonemerging topics: Pharmaceutical companies prefer to avoid surprises. The worst situation for a company is the unknown and its associated risks. Therefore, the two major benefits of harmonization (i.e., allowing for a global development plan supporting global registration and decreasing the unknown and its risks) outweigh the potential flexibility of having diverse requirements. Moreover, if there is a good scientific reason not to follow a guideline/recommendation, the company will always have the opportunity to discuss this deviation to general rules via scientific meetings during development.

-

▸

For new emerging topics and therapies: Regulator and innovative companies’ interactions during development will always be necessary. Development of a new class of compound or the first products to treat a new indication or disease will always need this type of interaction and sometimes a creative development program. Even if a proactive discussion is put in place between DRAs for new emerging topics, the role of this discussion will be to agree on terminology, endpoint, etc. The relevance and importance of the dialogue between the regulators and the first company developing such medicines will still be critical.

Finally, some industry resistance may also come from the fear of creating a global system that would deliver a common global decision that, in the case of a negative outcome, would mean refusal in all countries worldwide. However, it is important to remember that a global system would not mean a global marketing authorization. Unlike the European integrated system, a global system could provide a concerted/shared evaluation of data, but not a common decision regarding risk/benefit assessment. Following the shared evaluation of technical data (or recognition of the assessment from another country), each national DRA would remain the decision-making body. Each country would conduct their individual regulatory decision-making process regarding the risk/benefit evaluation following their own procedures and requirements. Each DRA would provide an independent decision, which could therefore still differ. This national decision-making process would also happen if a global mutual recognition procedure were to be established.

II-1.4). Would Further Cooperation and Harmonization Be Possible and Beneficial?

As presented in Part I, a substantial amount has already been done to harmonize pharmaceutical regulations. Many harmonization initiatives (i.e., bilateral, regional, and global) have already been established. The combination of this proactive collaboration with the natural convergence of issues and priorities on a worldwide basis (due to the globalization of trade and development/manufacture of pharmaceutical products) led to the convergence of requirements. However, there is still divergence between countries on many topics. More can be done to continue to protect and promote global public health (e.g., further harmonization and support for international clinical studies, better proactive support for the development of global standards related to emerging issues and new technologies, closer cooperation between DRAs, etc.). Moreover, the lack of international coordination of all harmonization initiatives is a problem. All of these ongoing initiatives remain segregated. ICH (via the GCG) and WHO initiated a type of coordination, but these efforts only promote good communication between the different players to share experiences and information on projects. Although such communication between global and regional initiatives is of course important, it is not sufficient. There is clearly a lack of leadership in the coordination of these initiatives and duplication of efforts. More proactive management of international actions needs to be established, and a global strategy (which would define clear objectives and responsibilities) needs to be agreed on. All current participants of the harmonization (at national, regional, and global levels) are critical, but the management of all these ongoing activities would certainly decrease duplication and would be more efficient and productive.

There is also an urgent need to increase access to priority essential medicines by reducing the time it takes for beneficial therapies to reach patients in need in developing countries/regions (such as Africa). However, lack of appropriate resources is a major and common problem in these countries (most of these countries have weak or nonexistent independent DRAs with experienced experts and reviewers). Harmonization of pharmaceutical regulations and cooperation at regional and international levels is an important element of the solution. Sharing resources between countries and use of international expertise (i.e., ICH) can resolve the problem if this cooperation is well structured and if the political support and legal framework are available in addition to funding. Moreover, the harmonization of regional regulation will develop new and bigger pharmaceutical market opportunities that will interest pharmaceutical manufacturers and therefore the development of medicinal products for the entire region. These opportunities would not be developed if each country has different standards and requirements for the registration of such products. Pharmaceutical companies usually focus their efforts first on major developed countries (i.e., the US and EU), as they are the major markets and the regulatory approval processes are more developed and transparent in these countries. They seek first approval for a new product in these regions even if the product is largely needed in developing countries. This practice can delay the entry of a new medicine in a developing country by 10 to 15 years. For example, for rotavirus infection, where the majority of between 352,000 and 592,000 children who die annually of its effects live in the developing world, this could mean thousands of deaths before medication is available [303]. The first rotavirus vaccine was initially available in the US where rotavirus is not as large of a health issue compared to developing countries, where a substantial number of children die due to this virus and where there is less access to medical treatments.

The vast majority of stakeholders support this continued harmonization effort and consider cooperation as the only solution to tackling the new challenges brought by the increased globalization of the pharmaceutical sector. Drug development and manufacture is indeed more and more global, therefore harmonization is more important than ever. In certain instances (e.g., regional integration process), harmonization and cooperation are critical, as divergences in national product standards often act as a barrier to trade and impede the creation of a free trade area or a single market.

The need for further cooperation and harmonization in the pharmaceutical sector (i.e., information exchange, joint assessments, and inspections) to reduce duplication has been clearly highlighted by worldwide regulators during the 14th International Conference of DRAs [304]. Major DRAs have also recognized the need to substantially change their operating models and to increase their global partnerships in order to address the challenges of the future [305]. Industry representatives have also strongly emphasized on numerous occasions that they support these activities and would welcome further worldwide harmonization of requirements.

Some resistance has, however, been raised, and these opponents to harmonization have criticized the significant costs, effort, resources, and time that such initiatives require. A 2005 article [306] even challenged the benefit of such projects. It argued that international harmonization is driven by industry and that there have been examples of less stringent requirements for drug approval at the international level than at the national level. Although additional efforts are necessary, the examples listed in this article are not fully representative of the overall situation. This negative position against harmonization is not shared by the majority of stakeholders, and numerous regulators have strongly repeated their support of international cooperation and harmonization. These criticisms against harmonization and cooperation will certainly fade away if global harmonization is developed in a coordinated and transparent fashion involving all stakeholders. However, it is important to take these concerns into account and continue to make sure that ICH and other international standards are developed based on appropriate and relevant scientific facts and discussions. Each harmonization project needs to be carefully evaluated in order to ensure that new proposed harmonized standards can be implemented and will bring benefit to global public health. The harmonization process demands money and many resources, so it cannot only be an intellectual exercise. The ultimate goal is not the harmonization of the technical requirements and processes themselves, but the improvement of public health and the increased timely access to quality, safe, and effective drugs on a worldwide basis. The harmonization process should clearly maintain or increase current levels of public health protection. In any case, it should not create “lower” standards. Also, harmonization and development of global standards should not imply reduction of medical alternatives. Although not beneficial for the entire population, certain traditional medicines can be valuable for certain subpopulations, regions, or countries. The global system therefore needs to allow for flexibility to develop these medicines and not restrict the choice to one global therapy.

If the harmonization process continues at the same pace as during recent decades, a global system of assessment and control of medicines (at least for specific products such as orphan drugs) will certainly be established as it presents advantages for all stakeholders. The multiplicity of registration procedures, and sometimes standards/requirements, obliged the pharmaceutical companies to set up priorities regarding worldwide submission plans. This can affect the availability of medicines in some small markets or countries. The establishment of a worldwide registration procedure, using international harmonized requirements, would be the only way to make sure that new therapies are available at the same time in both major and small markets. By improving the transparency, predictability, and efficiency of regulatory processes, the global system would also contribute to reducing unnecessary regulatory burden and promoting industry compliance. It would also facilitate the communication and coordination of pharmaceutical activities for emerging diseases and crisis management.

Today, this ultimate step of harmonization and cooperation seems far away and very difficult to implement. However, the European pharmaceutical regulatory system was also considered impossible to implement in 1939, but its success, in a relatively short period of time, demonstrated it was indeed possible! Although the European integration model cannot be applied to establish a global system, it demonstrates that the many challenges and resistance against harmonization/cooperation can be overcome if appropriate decisions are taken. More specifically, the European experience demonstrated that:

-

▸

Cooperation between (and even integration of) countries with different economic and societal/cultural environments and pharmaceutical markets is possible.

-

▸

Legal enforcement of harmonization (i.e., the creation of a mandatory implementation of harmonized topics) facilitates and accelerates harmonization.

-

▸

Political support is essential to achieve major harmonization objectives.

-

▸

Implementation of ICH guidelines in countries with less-developed regulatory systems is possible (e.g., EU enlargement to the Eastern European countries in 2004).

-

▸

Regional cooperation facilitates global harmonization and implementation of ICH guidelines.

-

▸

Partnership between central bodies (i.e., EMA, European Pharmacopoeia [EP], EU control laboratory network) and national DRAs is possible as long as roles and responsibilities are clearly defined.

-

▸

Countries can recognize the assessment performed by one rapporteur or another country (i.e., inspection or assessment of an application) if they agree on the standards used for evaluation.

Of course, implementing a global system may be more difficult than establishing the European system as there is no integration objective and therefore no economic/political pressures to create a single market, as was the case in Europe. However, it is possible if there is a political commitment. Scientists, regulators, and pharmaceutical companies have already shown, via their cooperation through ICH, WHO, and regional and bilateral collaborations, that they are ready for the next phase of harmonization.

Harmonization is a long process and the establishment of a global system will take time. The establishment of this global system can only be foreseen as a long-term stepwise project. It will require a lot of effort and commitment to progressively plan, organize, and implement several measures (at national, regional, and global levels) that will gradually structure international cooperation. Continuous political support will be crucial through the entire process. The politics should help in defining the scope and objectives of the cooperation, but the harmonization process should be left to technical and scientific experts. Without political support and a well-defined, science-driven, stepwise plan focused on public health, the establishment of a global system will remain elusive.

To ensure ultimate success, this harmonization process needs to evolve and take into consideration the economic, political, and other parameters (discussed in Part II-2). Indeed, these measures need to integrate the current political and economic context. Any short-term utopian measure or action that would not fulfill the current political and economic interests (e.g., developing a global supranational system that would give global approvals via a centralized procedure without consulting the national or regional DRAs) would be unrealistic, unreasonable, and therefore not viable. Long-term major changes will only be possible when organization is in place and based on the (geo)political evolution, as was the case in Europe.

Also, to be successful and beneficial for everyone, the new global system needs to be customized and take into account the specific and varying needs of all countries. Countries are indeed very different in terms of medical practice, legal obligations, level of development, etc. This diversity has to be taken into account when developing the global system. Moreover, it is important that this evaluation and the proposed improvements take into account the different regulatory capacity of all countries. Some countries do not have the expertise and resources to ensure that high standards are met. Is it therefore necessary to impose a costly investment to implement all global harmonized guidelines in all countries? The answer to this question is complex. Of course, certain global standards (e.g., GMP or GCP) need to be implemented similarly in all countries for ethical reasons, and also because medicines and data produced in one country will be used on a worldwide basis. However, it is not fair and/or practical to impose all new “high-level requirements” on developing countries. The cost of implementation can be too high for some requirements that may not be critical in a developing country as these requirements may require state-of-the-art science, equipment, expertise, and resources not available in these developing countries. A balance should therefore be found between the necessary implementation of high standards that not only support public health, but also the realities of developing countries. Increasing the requirements without benefit to public health could have major negative impact on the economy and development of these countries. Introducing high standards for all medicines without differentiation could lead to the failure of providing treatments for neglected diseases in developing countries [307]. The development and commercialization of these treatments are only interesting for small companies in developing countries (not multinational companies). Because they are relatively unprofitable for major pharmaceutical companies, R&D efforts aimed at new treatments for certain tropical diseases, as well as the availability of existing products, have decreased. If small pharmaceutical companies interested in developing and commercializing these medicines are limited by the need to comply to general high global standards (developed by ICH for all new medicines without distinction), such treatments will no longer be available. Therefore, careful evaluation of the benefit and potential negative impact of any new harmonization initiatives (especially global initiatives) needs to be conducted and mechanisms need to be in place to allow appropriate flexibility in the treatment of certain diseases.

In summary, the thorough evaluation of the current system outlined in previous sections makes it evident that harmonization of pharmaceutical regulations offers many direct benefits to both DRAs and the pharmaceutical industry, with beneficial impact for the protection of public health. Key benefits include better monitoring of medicines; preventing duplication of clinical trials in humans and minimizing the use of animal testing without compromising safety and effectiveness; streamlining the regulatory assessment process for new drug applications; allowing more informed decisions; and reducing development times and resources for drug development. However, although previous and ongoing harmonization and cooperation initiatives have already been beneficial, major improvements are still possible and would clearly provide many advantages to all stakeholders. It would help developing countries by providing expertise, experience, and support, but it would also help developed countries by ensuring better control of the medicines used in their countries that were developed and manufactured outside their own borders. Today, a population’s health suffers or benefits not just from its own domestic regulatory environment, but also from decisions made outside the country. All the positive initiatives and dedication seen in recent decades at the national, regional, and global levels need to be leveraged so that this collective knowledge and these resources continue to improve global public health.

The establishment of a coordinated global pharmaceutical system would have a significant added value on the promotion and protection of global public health. The recommendations presented in Part III have been developed with the following questions in mind: What is the best structure and process for this global pharmaceutical system, and how can this framework/network be realistically implemented?

II-2). Critical Parameters and Influencing Factors for Cooperation, Convergence, and Harmonization

Following the review of the status of all ongoing initiatives (Part I), we concluded that further harmonization would be beneficial for all stakeholders (Part II-1.4). However, to effectively discuss how to organize these next steps of harmonization, it is critical to first analyze the lessons of the past and the ongoing harmonization initiatives to understand what the critical parameters of harmonization and its influencing factors are. This analysis is essential to ensure success of the next necessary steps.

II-2.1). Critical Parameters for Cooperation, Convergence, and Harmonization

II-2.1.1). Regulatory Capacity (i.e., Resources, Expertise, Infrastructure)

A pharmaceutical regulatory system, supported by relevant legislation, is an essential component of a functioning healthcare scheme. This regulatory system includes, at the very least, the necessary legislation and regulations, and an authority that controls all pharmaceutical products through pre-marketing evaluation, marketing authorization, and post-marketing surveillance. It should also include an inspectorate, access to a medicine quality control laboratory, enforcement mechanisms, and safety monitoring [308].

Implementation of medicine policies has improved over the years [309], but there are still important problems. The level of effectiveness of national regulations varies widely across countries, as regulatory capacity is very different from one country to another. Some have mature, well-developed, and well-resourced systems, while others have weak or no regulatory system at all. For various reasons, many DRAs do not have the full capacity to perform all regulatory functions. In some countries, the inclusion of the regulatory functions as a department of the Ministry of Health also creates some challenges [310,311][310][311].

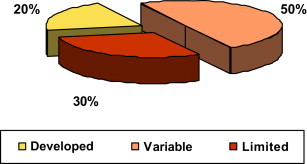

As presented in Figure 4 , there are important differences in regulatory capacity among all the WHO Member States [312].

FIGURE 4.

Differences in Regulatory Capacity Globally.

Source: Overview on medicines regulation: regulatory cooperation and harmonization in the focus, Presentation from Dr. Samvel Azatyan (WHO) at the WHO/UNICEF Technical Briefing Seminar on Essential Medicines Policies, 31 October – 4 November 2011, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland.

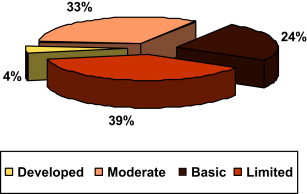

Even in a given region, regulatory capacity can vary. For example, Figure 5 shows that in Africa, among 46 WHO Member States, there are major differences.

FIGURE 5.

Differences in Regulatory Capacity in the African Region.

Source: Overview on medicines regulation: regulatory cooperation and harmonization in the focus, Presentation from Dr. Samvel Azatyan (WHO) at the WHO/UNICEF Technical Briefing Seminar on Essential Medicines Policies, 31 October – 4 November 2011, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland.

Also, personnel resources of DRAs vary from one or two people in small countries [313] to thousands of people in developed countries. For example, the US FDA employs approximately 15,000 people, with approximately 4,500 dedicated to the assessment and control of biologics and drugs [314,315][314][315].

This worldwide variation needs to be taken into consideration when discussing the organization of international harmonization and cooperation because harmonization projects require time, money, resources, and expertise. Without regulatory capacity, it is indeed difficult for a country to be involved in harmonization initiatives. Moreover, due to these resource constraints, the requirements developed and successfully implemented in one country may not be equally successful in another.

Many governments do not seem to recognize the potential benefits of a strong medicine regulatory system, and do not make the necessary political and financial commitments to secure one [316]. However, in many instances, the issue is not a lack of political support, but a lack of appropriate mechanisms capable of translating the high degree of political commitment into concrete programs of community building and integration. In other words, the politicians are willing to initiate the activities, but they do not have the resources and infrastructure to support this ambition. Indeed, a lot of countries do not have the resources, capacity, and expertise to implement such a functioning regulatory system [317]. Their main challenges are the following:

-

▸

Costs associated with the development of a regulatory system, participation in harmonization, and implementation of agreed-upon common standards

-

▸

Limited human and financial resources and institutional capacity

-

▸

Lack of effective legislation

-

▸

Lack of technical expertise and a trained staff

-

▸

Lack of supportive environment (i.e., no policy framework and no legislation) and quality management systems

For example, according to Dr. José Luis Di Fabio (of the Area of Technology, Health Care and Research, Pan American Health Organization [PAHO]/WHO), 65% of the countries in the Americas have a regulatory authority, but most do not have the capacity to evaluate and regulate products [318]. The challenge in these countries is to develop the expertise and systems in order to raise the level of regulation and confidence and therefore allow recognition of this specific authority and system. Mutual recognition is indeed based on the confidence in all countries’ DRAs. This is why PAHO/WHO developed the “qualification procedure” for authorities.

Also, an assessment of medicines regulatory systems in 26 Sub-Saharan African countries over a period of eight years showed that, although structures for medicine regulation existed in all countries assessed (and the main regulatory functions were addressed), in practice, the measures were often inadequate and did not form a coherent regulatory system. Common weaknesses included a fragmented legal basis in need of consolidation, weak management structure and processes, and a severe lack of staff and resources. On the whole, countries did not have the capacity to control the quality, safety, and efficacy of the medicines circulating in their markets or passing through their territories [319].

This capacity issue is amplified by the fact that the sparse healthcare resources in these developing countries need to also manage other major public health issues. Most of the countries recognize the value of harmonization and cooperation (especially for developing countries), but the shortage of resources requires prioritization. Presently, harmonization is one of the priorities for developed countries (e.g., the EU or US are both involved in many global, regional, and bilateral initiatives), but it is not the first priority for less-developed countries. Their focus regarding the public health sector is, rightly, the prevention and control of certain emerging/resurging infectious and communicable diseases such as dengue, cholera, tuberculosis, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), avian influenza, and typhoid fever, along with the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS. They also need to ensure access to quality essential medicines and low-priced generic products; in addition, the fight against substandard and counterfeit medicines is a growing issue.

In conclusion, it is evident that building regulatory capacity in developing countries is critical to allowing them to benefit from global harmonization, which in turn would benefit global public health. This support, with appropriate funding and resources, needs to be customized to their realities and needs. Complex systems and regulations from developed countries are not an appropriate response. The first focus should be to establish national and/or regional DRAs with appropriate powers in order to control the pharmaceutical market. Even with limited resources, this national or regional contact is necessary to liaise with other countries and develop a strategy and system based on a country’s individual needs. Many resources are available (e.g., via the WHO programs) to establish a pharmaceutical system and regulations appropriate to the level of development of the country [320]. To address the current issues in developing countries, it is also evident that national capacity building needs to be supported by regional and global cooperation and coordination.

II-2.1.2). Communication

Effective communication enhances cooperation, which in turn facilitates harmonization, especially for some cultures.

One of the initial steps of any harmonization initiative is to identify the main contacts (with the appropriate decision-making powers) from each party and build a strong communication channel between the identified parties. Understanding each other’s needs and challenges facilitates the building of trust and confidence in each other. This establishment of relationships between parties is key to a successful collaboration, as it will define the communication style throughout the entire process.

Good communication is key during all steps of the harmonization process, from initiation to implementation of the harmonized rules. But building strong communication based on mutual understanding and trust takes time, and many parameters can influence it (i.e., culture, distance between partners, fluency in English, etc.). Development and training of regulators on cultural differences and foreign languages (especially English) is obviously an important prerequisite to collaboration. For example, one of the first measures that the PMDA put in place to increase its international activities was to strengthen its foreign language training and daily educational activities in order to help relevant staff members improve their foreign language skills [321]. In addition, PMDA has also made efforts to improve and expand the English version of its website to provide the latest information in English [322].

Communication also involves the “human” factor. This human interaction should not be underestimated because good relationships and understanding of each other’s differences can facilitate the discussions/exchange and vice versa [323]. Indeed, harmonization does not only require infrastructure and resources, it requires willingness from the different players to communicate and exchange successfully. For example, during my research, regulators reported that some regulators from the US FDA or Health Canada have sometimes had more information and updates on activities happening in Europe than some small national European DRAs due to their close and regular communication with the EMA or certain national DRAs. Of course, as already mentioned in the previous section, Europe is a great example of harmonization. But even in this region that is mostly harmonized and integrated in terms of pharmaceutical regulation, there is some miscommunication occurring.

Changes in international trade and data protection [324,325][324][325], brought on by increased globalization, must also be considered. More specifically, the protection of commercially confidential informationa is an important issue because it impacts the communication and exchange of information between countries. It is obvious that it is important that DRAs exchange the maximum amount of information to achieve effective communication. Today, however, pharmaceutical companies and manufacturers provide different levels of information and data to different countries due to the risk associated with the dissemination of trade secrets. There is a concern that if major DRAs share information with “developing” DRAs, a leak could occur and proprietary/confidential information could become publicly available (e.g., proprietary information on a brand could be available to generic companies in developing countries). Consequently, most of the agreements between DRAs exclude the exchange of trade secret information and proprietary information and data (i.e., under these agreements the DRAs cannot exchange proprietary information/data on specific products). Regulators believe that these limitations have an important impact on cooperation as they limit communication and the exchange of information with other DRAs. This limitation would become even more problematic if a global framework for the evaluation of medicines (i.e., a EU Mutual Recognition Procedure [MRP]-type procedure) was established.

Pharmaceutical companies are already evaluating the pros and cons to registering a product in certain countries, especially where there is no (or limited) data exclusivity legislation in place, even if there are patent laws, because such laws are not always respected [326]. In this case, the harmonization of regulation between countries will obviously not be beneficial because medicines will not be registered and, therefore, available globally. To respond to this situation, several countries (including China and India) have started to issue “compulsory licenses” for local generic makers to produce drugs that are still within the patent life [327]. This amendment of legislation will certainly increase the concerns of pharmaceutical companies regarding trade secret information. In the case of China, the legislation amendment permits domestic firms that receive the licenses to be able to apply for permission to export their versions of the patented drugs for “reasons of public health,” which can cover a broad range of situations.

This problem of communication of trade secrets and confidential information therefore needs to be taken into consideration when developing global harmonization, worldwide cooperation mechanisms, and communication channels. Appropriate measures should be in place to balance the needs of developing countries to have access to essential medicines, but at the same time to avoid dissemination of confidential data that could impact innovation.

Finally, good communication between parties requires appropriate mechanisms and tools:

-

▸

Firstly, it is important before discussing harmonization to have a glossary to ensure that all parties use the same “language” because the different regulations impose conflicting definitions/terminology (e.g., definition of a medicinal, biotechnological, or biological product). The development of internationally recognized nomenclatures and classifications have been an important part of ICH and WHO work, and many tools have been developed (CTD, MedDRA, INN, ICD, ICF, ICHI, ATC, DDD, etc.). Moreover, the product classifications and/or nomenclatures need to be harmonized (especially in the case of an integration model) to facilitate communication and exchange of information between different national DRAs. Different brand/proprietary names of the same product in different countries can be confusing. Different nonproprietary names are a bigger problem. This issue has been partly resolved with the creation of the INN by the WHO. Indeed, before INN, the differences in nonproprietary names around the world were an issue (e.g., paracetamol vs. acetaminophen). These different names were given by different national bodies using different naming conventions. Today, INN is the worldwide standard for names. Unfortunately, in the US a USAN name is still a requirement (most other countries accept an INN-approved name). Moreover, USAN still has a different naming convention than the INN. Even if most of the new products have the same USAN and INN name, these different naming conventions can create some issues when a company wants to register a new name globally, creating conflicting feedback and positions that can take years to resolve.

-

▸

Secondly, harmonized and common training is very important between reviewers from different countries. This part of harmonization was recognized in Europe very early on in the process [328]. It facilitates the implementation of harmonized, high-quality performance standards, increases consistency in review/inspection, and decreases the discrepancies in the implementation of these standards.

-

▸

Thirdly, telecommunication and informatics infrastructures are important to ensure efficient communication. Appropriate communication tools supporting rapid and easy communication between parties (especially in the case of safety issues) need to be in place. In some countries, this communication (and exchange of information) is sometimes difficult due to the lack of infrastructure (e.g., computers). This lack of infrastructure has some impact on communication (i.e., connection to a safety/PhV database or clinical trial application). Basic communication tools such as communicating via e-mails or access to the Internet can still cause serious problems.

II-2.1.3). Definition of Clear Goals and Appropriate Planning

Harmonization is a long and stepwise process that requires huge effort and focus!

All successful harmonization arrangements to date (i.e., ICH, EU, etc.) have taken a significant amount of time to develop. They required numerous meetings, technical discussions, and complex negotiations to resolve scientific differences and/or legal issues. If the process had moved too fast, people may have been concerned about certain issues (e.g., losing their independence), and the success of the project may have been impacted. Trust and acceptance needs time, as evidenced by the establishment of relationships and cooperation between the ICH and non-ICH regions. The GCG was created in 1999, and it took almost 10 years for the GCG/ICH to create real partnerships with the Regional Harmonization Initiatives (RHIs). This time was necessary to get to know one another and to understand each other’s needs and challenges in order to establish the high level of trust, understanding, and respect necessary before setting up practical actions for the implementation of ICH guidelines in non-ICH regions (via training, shared meetings, etc.).

The most prevalent reasons for failure of alliance and cooperation projects are related to the lack of upfront clear specific goals and appropriate planning and structure (i.e., underestimation of time and the skills required) [329]. To be efficient and avoid any confusion, it is therefore important to clearly determine up front the scope and objective of the initiative. This alleviates future discussion and allows the focus to be on actions. It is also critical to establish a plan, with intermediate goals, in order to remain focused on the ultimate objectives. For example, ICH has worked since its creation towards harmonization of technical topics, while the EU developed a structure and system for harmonizing the laws and regulation of its member countries to promote both public health and the free circulation of pharmaceuticals within the European trade areas. Though these two organizations both work towards regulatory harmonization, they are very different as they have very different objectives.

True harmonization is much more than common documentation and standards. The objective is to have similar or collaborative approaches to medicine registration that ultimately allows for mutual recognition and/or centralized registration (if desired) in the long term. But this is a long process and it requires effective communication and collaboration (e.g., information sharing and working jointly) to understand similarities and differences and to build trust. The reality of resources and efforts needs to be taken into account when establishing this plan. Therefore, project planning and management is key.

Major steps can be distinguished as follows:

-

▸

A general exchange aimed at enhancing collaboration and mutual understanding.

-

▸

The formulation of a framework agreement as the formal basis to start the harmonization process.

-

▸

The development of harmonized nomenclatures and procedures.

-

▸

The adoption of harmonized product and qualification standards.

-

▸

The mutual recognition of the harmonized standards.

-

▸

Compliance to apply consistent practices in selected areas.

-

▸

Maintenance and update of a harmonized topic: Harmonization of the regulation is not a one-time activity. Science is not static, so harmonization of the technical requirements should not be static. Processes need to be put in place to ensure that when the fundamentals, assumptions, and science evolve, the agreement will be reassessed (and changed if necessary) to avoid countries evolving on their own.

Although the above sequence seems simple, in practice the tasks are tedious, and often initiate challenges that require systematic and thorough resolutions.

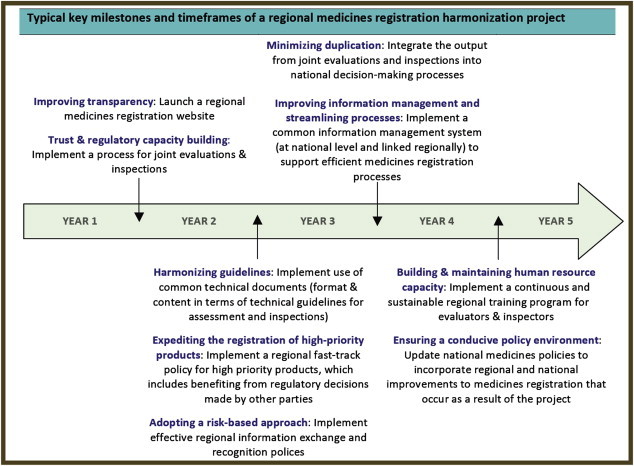

The African Medicines Registration Harmonization (AMRH) Initiative determined typical key milestones and timeframes for its regional medicines registration harmonization projects. This model, presented below in Figure 6 , can be generalized to any other worldwide harmonization project (i.e., international, regional, or subregional). Although each harmonization initiative can differ in its specific content and duration (due to the baseline level of harmonization and other legal, cultural, and political factors), the concept and process is always the same. This process takes time and the coordination of communication and the predetermination of a structured plan and process is critical.

FIGURE 6.

Model of Typical Key Milestones and Timeframes for Harmonization Projects.

Source: “African Medicines Registration Harmonization (AMRH) Initiative: Summary, Status and Future Plans,” NEPAD and WHO, November 2009.

II-2.1.4). Organization and Structure

The review of ongoing harmonization initiatives in Part I showed that there are different models of cooperation based on the scope and objectives of the project. They can range from a simple technical collaboration to full harmonization and integration of systems and regulations. Depending on the model, different options can be selected to enhance regulatory cooperation, each of these options requiring a different degree of collaboration and time to impact [329].

All successful organizations have an appropriate structure to coordinate efforts (ICH, WHO, and Europe are good examples). Harmonization is an intense process that requires dedicated resources and infrastructure to be successful. Responsibilities, duties, and functions need to be defined and distributed appropriately between the bodies.

At the very least, a harmonization initiative needs to be supported by:

-

▸

An oversight committee (called a “Steering Committee” or “Governance Committee”): The role of this committee is to set up priorities, coordinate actions and projects, and monitor those activities to ensure appropriate development towards predefined goals.

-

▸

A secretariat: The role of the secretariat is to support the administrative work and to provide project management. Transparency of the process requires publication of an agenda and meeting minutes, and dissemination of harmonized standards and decisions, etc.

Communication is also critical between the national institutions and regional or international initiatives. A designated contact needs to be established between national activities and regional/international discussions to avoid duplication of effort or even conflicting decisions. This contact is essential to (1) feed the regional and international discussion with specificities/challenges/etc. from the country; and (2) ensure good implementation of agreed-upon harmonized standards.

Finally, the structure and organization of harmonization initiatives also needs to evolve as the program evolves. A specific structure may be ideal for certain phases of harmonization/cooperation but not relevant for others. An early initiative needs a limited relationship at a high level, and the involvement of a finite number of people. However, the integration phase requires more stable and defined institutions. For example, SADC’s structure evolved over time. It started as a “Coordinating Conference” (with limited institutions and focused on coordination of national actions) before becoming a “Development Community” (with defined institutions and a focus on integration). To support this evolution, SADC’s structure changed over time, and is regularly evaluated to ensure that it adequately supports the initial objectives.

II-2.1.5). Implementation and Monitoring

After reaching agreement, the harmonized rules and standards need to be implemented, a key phase of any harmonization initiative. However, this ultimate step is not simple, and disharmony could still exist if the agreement is not adopted consistently in all regions.