Abstract

Objectives

To describe the duration of time to achieve exclusive oral feeding in infants with single ventricle physiology and to identify risk factors associated with prolonged gastrostomy tube dependence.

Study design

Single center, retrospective study of infants with single ventricle physiology. The primary outcome was duration of time required to achieve oral feeding. Transition periods were defined as exclusive oral feeding by Glenn palliation (early), by 1 year of age (mid), or after 1 year of age (late).

Results

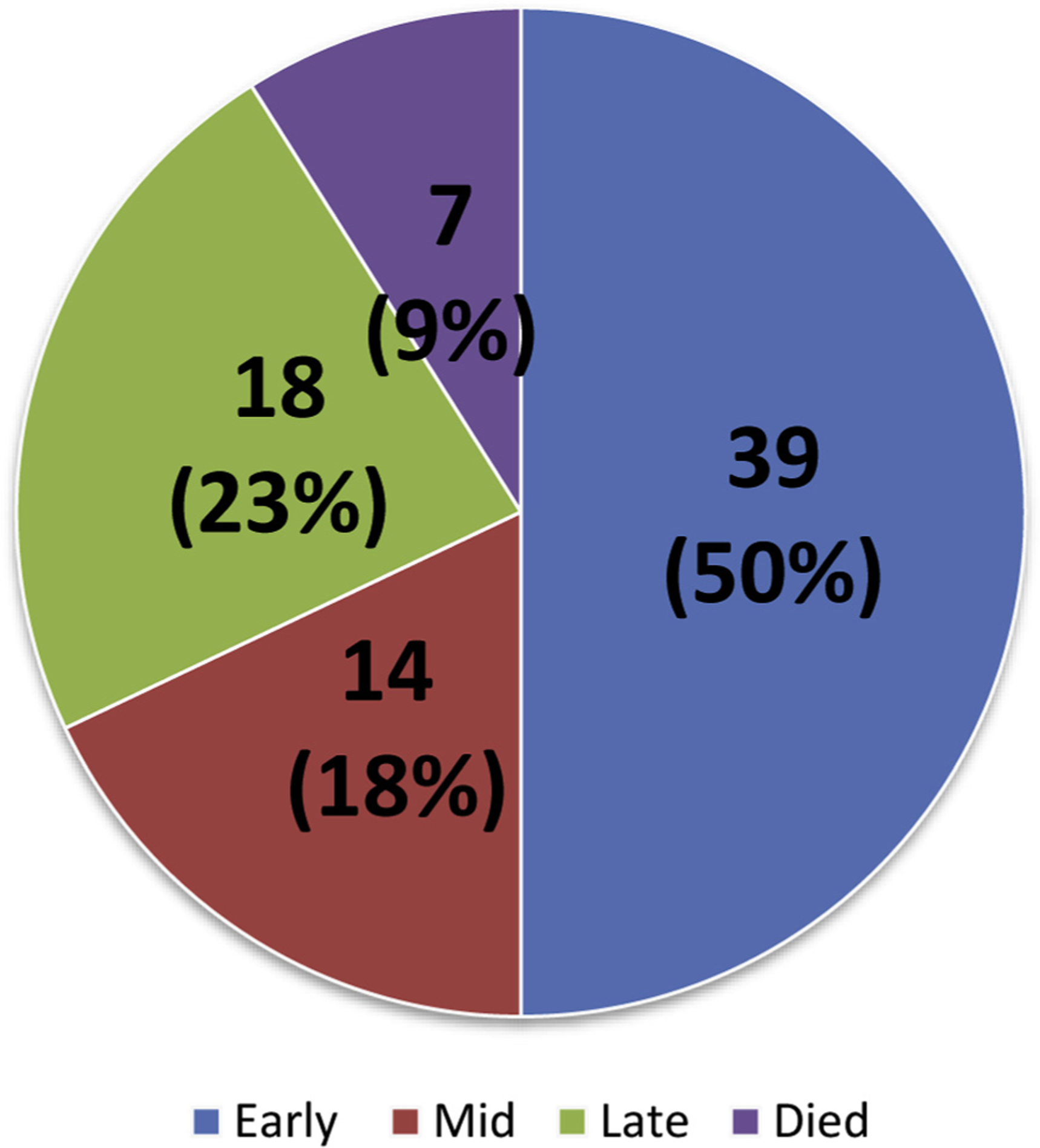

Seventy-eight infants were analyzed; 46 (59%) were discharged to home with a gastrostomy tube after the initial hospitalization. Overall, 39 infants (50%) achieved early transition, 14 (18%) mid, and 18 (23%) late. The group who achieved early transition had a higher percentage of preoperative oral feeding (P < .01), greater weight-for-age z score at initial discharge (P = .03), shorter initial intensive care unit duration (P < .01), shorter initial hospital length of stay (P < .01), and greater weight-for-age z score at Glenn admission (P = .02). No preoperative oral feeding (OR = 0.12, P = .02) and greater number of cardiac medications at initial discharge (OR = 3.8, P = .03) were associated with failure to achieve early transition. No preoperative oral feeding (OR = 0.09, P = .01) and longer initial intensive care unit duration (OR = 1.1, P = .03) were associated with failure to achieve mid transition.

Conclusion

Preoperative oral feeding may potentially be a modifiable factor to help improve early transition to oral feeding.

Despite improved surgical and survival outcomes, infants with single ventricle physiology (SVP) remain at risk for significant comorbidities including prolonged feeding tube dependence.1,2 Feeding tube dependence has been associated with developmental delays, increased risk of interstage mortality, and longer hospitalization at the time of bidirectional Glenn palliation.3–6 In an analysis of the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative registry, Cross et al identified feeding route as the most potentially modifiable risk factor for interstage mortality.4 Tube feeding in medically fragile children and feeding concerns in the interstage period are significant causes of anxiety among caregivers.7 Despite the prevalence of prolonged feeding tube dependence amongst infants with SVP, there is a paucity of data describing the duration of feeding tube dependence and the risk factors for delayed transition to oral feeding.

Methods

This was a retrospective, single center, chart review study. The Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina approved the project. The study cohort included all infants with SVP who underwent staged surgical palliation and survived to hospital discharge between January 1, 2012 and March 30, 2017. Infants were excluded if they did not require surgery in the neonatal period and underwent the Glenn shunt as their first surgery. The primary outcome of this study was the duration of time required to achieve exclusive oral feeding. Feeding transition periods were defined as exclusive oral feeding by bidirectional Glenn palliation (early), by 1 year of age (mid), or after 1 year of age (late). Data were collected from the electronic medical record and included birth, initial hospitalization, interstage period, Glenn hospitalization, and post-Glenn data.

As part of standard institutional practice, all infants who underwent aortic arch reconstruction or had a hoarse cry after extubation had vocal cord evaluation with direct laryngoscopy prior to hospital discharge. All infants who underwent aortic arch reconstruction or demonstrated impaired swallowing function by bedside evaluation underwent formal swallowing assessment with a speech therapist and modified barium swallow study prior to hospital discharge. Infants who were unable to achieve goal caloric requirements by oral feeding underwent laparoscopic gastrostomy tube (GT) placement prior to hospital discharge. Inpatient nutrition and feeding management were discussed on a daily basis with the cardiac dietitian as part of multidisciplinary rounds. Standardized perioperative feeding practices, including preoperative management, were adopted in 2013 and mirrored the algorithms published by the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative.8 As part of standard clinical care, infants with SVP were closely followed in an interstage monitoring program until the bidirectional Glenn and then subsequently in the Medical University of South Carolina cardiac neurodevelopmental clinic. Nutrition and feeding during the interstage period were managed by the same multidisciplinary team throughout the duration of the study period.

Neurologic injury was defined as documented clinical seizures, abnormal electroencephalography, or abnormality on brain magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography. As part of standard institutional cardiac intensive care unit (ICU) practice, infants who required a continuous opiate and/or benzodiazepine infusion for longer than 7 days were transitioned to an enteral methadone and/or lorazepam taper. Prolonged enteral sedation was defined as a methadone and/or lorazepam taper that exceeded 7 days in duration.

Continuous variables were described using mean and SD or median with IQR. Differences between group were assessed using ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. Categorical variables were described using frequency and percentages. Between group analyses were performed with the Fisher exact test. Stepwise multinomial logistic regression was used to identify independent risk factors for delayed transition to oral feeding. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS (Armonk, New York).

Result

Seventy-eight infants were included in the analysis. The study cohort’s clinical characteristics and initial hospitalization are described in Table I. All infants who were unable to achieve goal caloric requirements by oral feeding during their initial hospitalization underwent laparoscopic GT placement prior to hospital discharge, and no infants were discharged to home with a naso- or orogastric tube. Thirty-nine infants (50%) achieved transition to exclusive oral feeding by Glenn palliation (early) and within this group, 32 (41%) infants were exclusively orally fed by initial hospitalization discharge and never required GT. Fourteen infants (18%) achieved transition to exclusive oral feeding by 1 year of age (mid), and 18 infants (23%) achieved transition to exclusive oral feeding after 1 year of age (late) (Figure). Seven infants (9%) died prior to transitioning to exclusive oral feeding. Of those 7 deaths, 6 infants died during the interstage period, the time between their initial hospital discharge and Glenn admission.

Table I.

Study cohort and initial hospitalization characteristics

| Sex | |

| Male | 46 (59) |

| Female | 32 (41) |

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | 38.2 ± 1.7 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.1 ± 0.6 |

| Chromosomal abnormality | |

| Yes | 10 (13) |

| No | 65 (83) |

| Unknown | 3 (4) |

| Extracardiac anomalies | |

| Yes | 12 (15) |

| No | 66 (85) |

| Ventricular morphology | |

| Left | 28 (36) |

| Right | 47 (60) |

| Indeterminate/mixed | 3 (4) |

| Peak preoperative lactate (mmol/L) | 3.8 ± 3.7 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (min) | 114.7 ± 107.3 |

| Aortic cross clamp time (min) | 26.9 ± 32.7 |

| Days on ventilator (d) | 13.9 ± 14.2 |

| ECMO | |

| Yes | 5 (6) |

| No | 73 (94) |

| Neurologic injury | |

| Yes | 14 (18) |

| No | 64 (82) |

| Vocal cord paralysis | |

| Yes | 6 (8) |

| No | 72 (92) |

| Aspiration on swallow study | |

| Yes | 28 (36) |

| No | 50 (64) |

| GT placement | |

| Yes | 46 (59) |

| No | 32 (41) |

| Preoperative oral feeding | |

| Yes | 36 (46) |

| No | 42 (54) |

| Preoperative enteral feeding (oral or tube) | |

| Yes | 52 (67) |

| No | 26 (33) |

| Prolonged enteral sedation taper | |

| Yes | 43 (55) |

| No | 35 (45) |

| Number of GI medications at initial discharge | 1.5 (0–3) |

| Number of cardiac medications at initial discharge | 2.0 (0–4) |

| Weight-for-age z score at initial discharge | −1.7 ± 1.1 |

| Length of initial hospitalization (d) | 54.1 ± 29.9 |

| Initial surgery | |

| Norwood | 29 (37) |

| Hybrid | 15 (19) |

| Systemic to pulmonary shunt | 26 (33) |

| Pulmonary artery band | 8 (10) |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; GI, gastrointestinal.

Categorical variables are listed n (%), continuous are mean ± SD or median (IQR).

Figure.

Transition groups.

Comparison of early, mid, and late feeding transition groups are presented in Table II. Compared with the mid transition group, infants who had early transition to exclusive oral feeding had a higher percentage of preoperative oral feeding (69% vs 21%, P < .01), fewer cardiac medications at initial discharge (2.0 ± 2.7 vs 2.7 ± 0.9, P < .01), shorter length of initial hospitalization (36.9 ± 13.7 vs 67.3 ± 39.7, P < .01), higher O2 saturations at initial discharge (87.0 ± 3.5 vs 83.5 ± 4.6, P = .03), and higher weight-for-age z score at Glenn admission (−1.0 ± 0.9 vs −2.0 ± 1.1, P = .02). Compared with the late transition group, infants who had early transition to exclusive oral feeding had a higher percentage of preoperative oral feeding (69% vs 11%, P < .01), higher weight-for-age z-score at initial discharge (−1.3 ± 1.0 vs −2.1 ± 1.2, P = .03), fewer intubation days during initial hospitalization (9.2 ± 10.8 vs 23.7 ± 19.7, P < .01), fewer cardiac medications at initial discharge (2.0 ± 2.7 vs 2.7 ± 0.8, P < .01), shorter initial ICU duration (22.9 ± 11.7 vs 54.4 ± 31.7, P < .01), and shorter length of initial hospitalization (36.9 ± 13.7 vs 75.3 ± 30.2, P < .01).

Table II.

Comparison of feeding transition groups

| Variable | Early | Mid | Late | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative oral feeding | 27 (69) | 3 (21) | 2 (11) | <.01*† |

| Preoperative enteral feeding | 28 (76) | 6 (43) | 10 (56) | .07 |

| Weight-for-age z score at initial discharge | −1.32 ± 0.97 | −1.94 ± 1.12 | −2.06 ± 1.16 | .03† |

| Number of intubations during initial hospitalization | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | .33 |

| Days of intubation during initial hospitalization (d) | 9.2 ± 10.8 | 13.8 ± 11.6 | 23.7 ± 19.7 | <.01† |

| Vocal cord paralysis | 1 (3) | 1 (7) | 3 (17) | .1 |

| Prolonged enteral sedation taper | 15 (39) | 11 (79) | 12 (67) | .02 |

| NEC during initial hospitalization | 2 (5) | 3 (21) | 4 (22) | .08 |

| Number of cardiac meds at initial discharge | 2 (2–2) | 2 (2–4) | 3 (2–3) | <.01*,† |

| Number of GI meds at initial discharge | 1 (0–2) | 2 (0–2.25) | 2 (1–3) | .12 |

| Initial ICU duration (d) | 22.9 ± 11.7 | 38.3 ± 30.8 | 54.4 ± 31.7 | <.01† |

| Length of initial hospitalization (d) | 36.9 ± 13.7 | 67.3 ± 39.7 | 75.3 ± 30.2 | <.01*,† |

| O2 saturation at initial discharge (%) | 87.0 ± 3.5 | 83.5 ± 4.6 | 87.1 ± 5.5 | .03* |

| Received speech, occupational, and/or physical therapies after initial hospitalization‡ | 22 (60) | 10 (71) | 14 (78) | .36 |

| Weight-for-age z score at Glenn admission | −1.00 ± 0.90 | −1.98 ± 1.06 | −1.72 ± 1.61 | .02* |

| AV valve regurgitation at Glenn discharge‡ | .02 | |||

| Mild | 18 (55) | 7 (54) | 3 (23) | |

| Moderate | 14 (42) | 3 (23) | 10 (77) | |

| Severe | 1 (3) | 3 (23) | 0 (0%) | |

| Received speech, occupational, and/or physical therapies after Glenn‡ | 15 (47) | 9 (69) | 11 (85) | .06 |

| Presence of extracardiac anomalies | 4 (10) | 1 (7) | 6 (33) | .07 |

AV, atrioventricular valve; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis.

Categorical variables are listed n (%), continuous are mean ± SD or median (IQR).

P < .05 between early and mid-groups.

P < .05 between early and late groups.

Missing data in some subjects.

Multivariable logistic regression demonstrated that no preoperative oral feeding (OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.02–0.75, P = .02) and greater number of cardiac medications at initial discharge (OR 3.82, 95% CI 1.16–12.54, P = .03) were independently associated with an inability to achieve exclusive oral feeding by Glenn palliation. No preoperative oral feeding (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.59, P = .01) and longer initial ICU duration (OR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.10, P = .03) were independently associated with an inability to achieve exclusive oral feeding by 1 year of age.

Discussion

Preoperative oral feeding may be a potentially modifiable factor to improve feeding dysfunction amongst infants with single ventricle heart disease. In this study cohort, preoperative oral feeding, even if just trophic volumes, was associated with an earlier transition to oral feeding. This finding suggests that early preoperative oral feeding prior to surgery may have protective benefits against postoperative oral feeding dysfunction. Feeding protocols in cardiac ICUs have shown benefits in identifying candidates for early feeding and safely advancing feeds to maximize both nutrition and oral motor coordination.8–10 Studies in the neonatal ICUs have shown that there is a sensitive period when infants are ready for specific developmental activities such as feeding to occur. If feeding does not occur during these “critical periods,” infants may develop oral aversion and refuse later oral feeding attempts.11 Implementing a comprehensive oral feeding program can encourage earlier transition to full oral feeds in neonates.11,12 This concept may be translatable to the cardiac infant population including neonates with SVP.

Fetal environment, brain development, and maturation play a significant role in early ability to feed, and these factors may be pathologically altered in fetuses with single ventricle heart disease.13 There is evidence that fetuses with cyanotic congenital heart disease have a decline in global brain growth and cerebral anaerobic metabolism compared with normal fetuses.13,14 Specifically, fetuses with hypoplastic left heart syndrome have been shown to have a progressive decline in volumes of gray and white matter compared with healthy controls.13 Decreases in subcortical gray matter were associated with lower neonatal neurobehavioral assessment scores.15 Postnatal brain magnetic resonance imaging of infants with critical congenital heart disease has demonstrated findings of periventricular leukomalacia similar to those of premature neonates.14,16 Although not directly measured in these studies, neurophysiologic changes of periventricular leukomalacia have been associated with feeding difficulties.11,13,15,16 Future studies examining the relationships of fetal brain development, an infant’s ability to feed by mouth, and the effects of a comprehensive early oral feeding therapy program are warranted in the single ventricle population.

Although the results of this study support preoperative enteral feeding, safety concerns and practice variation pose barriers to the use of enteral nutrition in actual clinical practice. The concern for mesenteric ischemia because of poor cardiac output, diastolic steal, and excessive pulmonary blood flow increase the risk for necrotizing enterocolitis.17–20 In addition, clinicians may be uncomfortable with enteral feeding concomitantly with vasoactive medications and pros-taglandins.20 However, despite the safety concerns, several recent single and multi-institutional studies have demonstrated that preoperative enteral feeding is not associated with an increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates with significant cardiac disease.9,17–19 With appropriate monitoring and clinical judgment, it seems reasonable to consider preoperative enteral feeding, at least trophic volumes, in the hemodynamically stable infant.

No preoperative oral feeding, greater number of cardiac medications at initial discharge, and longer initial ICU duration were associated with delayed transition to oral feeding in this study cohort. Secondary analysis of the Pediatric Heart Network’s Single Ventricle Reconstruction Trial also demonstrated similar findings with significant associations between tube feeding dependence, longer ICU course, and greater number of cardiac medications at hospital discharge. However, that study did not examine if these factors predicted later transition to oral feeding.21 Infants who required longer ICU courses and more cardiac medications at hospital discharge may have worse overall illness including congestive heart failure and compromised ventricular function, contributing to an inability to transition to oral feeding at an earlier age. An inability to transition to oral feeding may represent increased severity of illness and can be used to risk stratify infants.5,21

The morbidities of feeding tube dependence during infancy have profound lifelong consequences in the single ventricle population, manifesting as continued feeding dysfunction and parental stress through the childhood years.6 Hill et al found that patients with SVP who required supplemental feeding had significantly more resistance to oral feeding and parental stress around feeding compared with other children referred to feeding clinic for noncardiac reasons, such as cerebral palsy or extreme prematurity.6 The significant impact of feeding dysfunction on a family’s overall quality of life highlights the importance of identifying modifiable factors to improve transitions to oral feeding.

There were limitations to this study. The retrospective nature of the study restricts the ability to predict if intervening on these variables would lead to earlier oral feeding. We did not take into account whether or not an infant was small for gestational age. We did not include the mortality risk of supplemental tube feeding in our analysis. The Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial found that failure to feed orally prior to Norwood hospital discharge conferred an increased risk for mortality.21,22 This study studied risk factors for delayed transition to oral feeding, but was not designed to determine adverse outcomes for those who were unable to transition to oral feeding. Lastly, clinical feeding practices changed during the study time period, specifically attitudes toward preoperative oral feeding. It is possible that the feeding protocol implemented in more recent years had an impact on the cohort’s ability to transition to oral feeding.

With the increasing utilization of standardized feeding protocols in cardiac ICUs, future studies are required to determine if protocol adherence improves transition to oral feeding. Further investigation of the role of fetal brain development and early comprehensive oral feeding therapy programs are also warranted.

Glossary

- GT

Gastrostomy tube

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- SVP

Single ventricle physiology

Footnotes

Portions of this study were presented at the American College of Cardiology Scientific Sessions, March 10-12, 2018, Orlando, Florida

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Golbus JR, Wojcik BM, Charpie JR, Hirsch JC. Feeding complications in hypoplastic left heart syndrome after the Norwood procedure: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Cardiol 2011;32:539–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill G, Silverman A, Noel R, Bartz PJ. Feeding dysfunction in single ventricle patients with feeding disorder. Congenital Heart Dis 2014;9: 26–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RV, Zak V, Ravishankar C, Altmann K, Anderson J, Atz AM, et al. Factors affecting growth in infants with single ventricle physiology: a report from the Pediatric Heart Network Infant Single Ventricle Trial. J Pediatr 2011;159:1017–22.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross RR, Harahsheh AS, McCarter R, Martin GR. Identified mortality risk factors associated with presentation, initial hospitalisation, and interstage period for the Norwood operation in a multi-centre registry: a report from the national pediatric cardiology-quality improvement collaborative. Cardiol Young 2014;24:253–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medoff-Cooper B, Irving SY, Hanlon AL, Golfenshtein N, Radcliffe J, Stallings VA, et al. The association among feeding mode, growth, and developmental outcomes in infants with complex congenital heart disease at 6 and 12 months of age. J Pediatr 2016;169:154–9.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill GD, Silverman AH, Noel RJ, Simpson PM, Slicker J, Scott AE, et al. Feeding dysfunction in children with single ventricle following staged palliation. J Pediatr 2014;164:243–6.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart J, Dempster R, Allen R, Miller-Tate H, Dickson G, Fichtner S, et al. Caregiver anxiety due to interstage feeding concerns. Congenital Heart Dis 2015;10:E98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slicker J, Hehir DA, Horsley M, Monczka J, Stern KW, Roman B, et al. Nutrition algorithms for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome; birth through the first interstage period. Congenital Heart Dis 2013;8: 89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alten JA, Rhodes LA, Tabbutt S, Cooper DS, Graham EM, Ghanayem N, et al. Perioperative feeding management of neonates with CHD: analysis of the Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium (PC4) registry. Cardiol Young 2015;25:1593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slicker J, Sables-Baus S, Lambert LM, Peterson LE, Woodard FK, Ocampo EC. Perioperative feeding approaches in single ventricle infants: a survey of 46 centers. Congenital Heart Dis 2016;11:707–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamitsuka MD, Nervik PA, Nielsen SL, Clark RH. Incidence of nasogastric and gastrostomy tube at discharge is reduced after implementing an oral feeding protocol in premature (<30 weeks) infants. Am J Perinatol 2017;34:606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gianni ML, Sannino P, Bezze E, Plevani L, Esposito C, Muscolo S, et al. Usefulness of the Infant Driven Scale in the early identification of preterm infants at risk for delayed oral feeding independency. Early Hum Dev 2017;115:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clouchoux C, du Plessis AJ, Bouyssi-Kobar M, Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Brown DW, et al. Delayed cortical development in fetuses with complex congenital heart disease. Cerebral Cortex 2013;23: 2932–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahle WT, Tavani F, Zimmerman RA, Nicolson SC, Galli KK, Gaynor JW, et al. An MRI study of neurological injury before and after congenital heart surgery. Circulation 2002;106(12 Suppl 1):I109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen M, Shevell M, Donofrio M, Majnemer A, McCarter R, Vezina G, et al. Brain volume and neurobehavior in newborns with complex congenital heart defects. J Pediatr 2014;164:1121–7.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Licht DJ, Shera DM, Clancy RR, Wernovsky G, Montenegro LM, Nicolson SC, et al. Brain maturation is delayed in infants with complex congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:529–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scahill CJ, Graham EM, Atz AM, Bradley SM, Kavarana MN, Zyblewski SC. Preoperative feeding neonates with cardiac disease. World J Pediat Congenital Heart Surg 2017;8:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willis L, Thureen P, Kaufman J, Wymore E, Skillman H, da Cruz E. Enteral feeding in prostaglandin-dependent neonates: is it a safe practice? J Pediatr 2008;153:867–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Natarajan G, Reddy Anne S, Aggarwal S. Enteral feeding of neonates with congenital heart disease. Neonatology 2010;98:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolovits JS, Torzone A. Feeding and nutritional challenges in infants with single ventricle physiology. Curr Opin Pediatr 2012;24:295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert LM, Pike NA, Medoff-Cooper B, Zak V, Pemberton VL, Young-Borkowski L, et al. Variation in feeding practices following the Norwood procedure. J Pediatr 2014;164:237–42.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghanayem NS, Allen KR, Tabbutt S, Atz AM, Clabby ML, Cooper DS, et al. Interstage mortality after the Norwood procedure: results of the multicenter Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:896–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]