To the Editor:

We read with great interest the recent articles by Repici et al1 and Soetikno et al.2 An outbreak of a novel coronavirus pneumonia spread rapidly through the whole country and is now a worldwide pandemic. Up until March 30, the National Health Commission of China reported a total of 82,423 confirmed cases in 31 provinces and 3306 deaths, in addition to 615,699 confirmed cases worldwide.3 With the development of the pandemic, more countries have become involved in this serious battle against the virus.

ERCP is an important and effective procedure of choice for biliary decompression. Despite the high danger of infection in COVID-19 outbreak areas, ERCP is still required for patients with emergent biliary obstruction and for those who cannot wait until the next available elective list. Direct contact, airborne droplets, contamination by touch, and uncertain fecal–oral transmission greatly increase the infection risk of ERCP procedures.4

To guarantee the safety of healthcare workers and patients for ERCP procedures, we established infection prevention measures and standard operating procedures in the endoscopy center of our gastroenterology department to guarantee a safe environment for both patients and healthcare personnel. Here, we report a retrospective review of ERCP procedures in 31 patients during the COVID-19 pandemic to evaluate the safety of these essential protective measures (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 ).

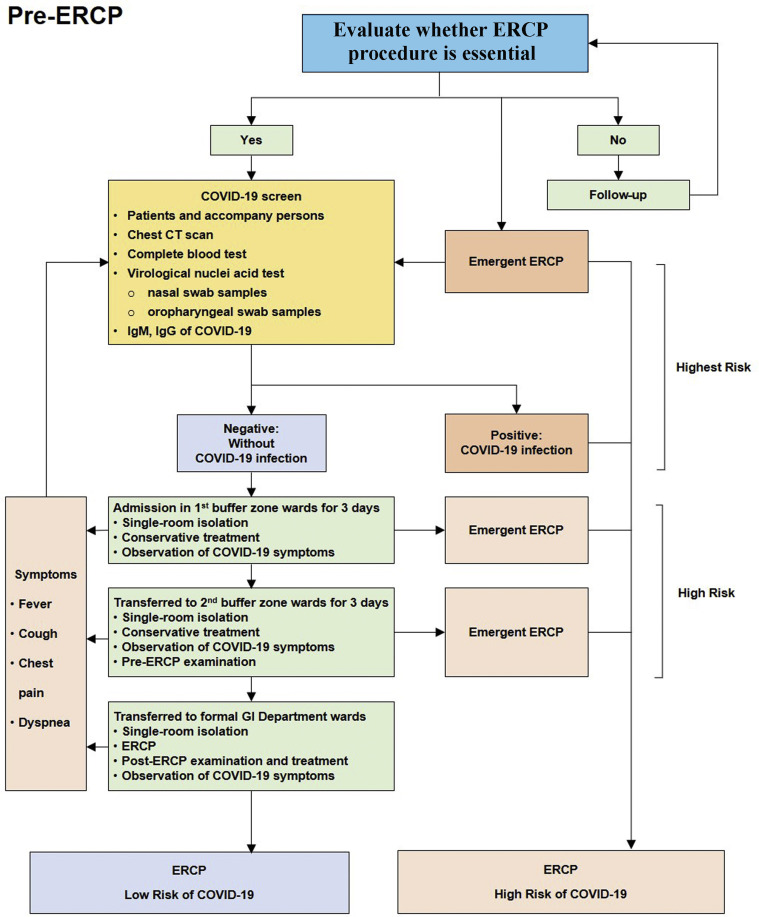

Figure 1.

Pre-ERCP management.

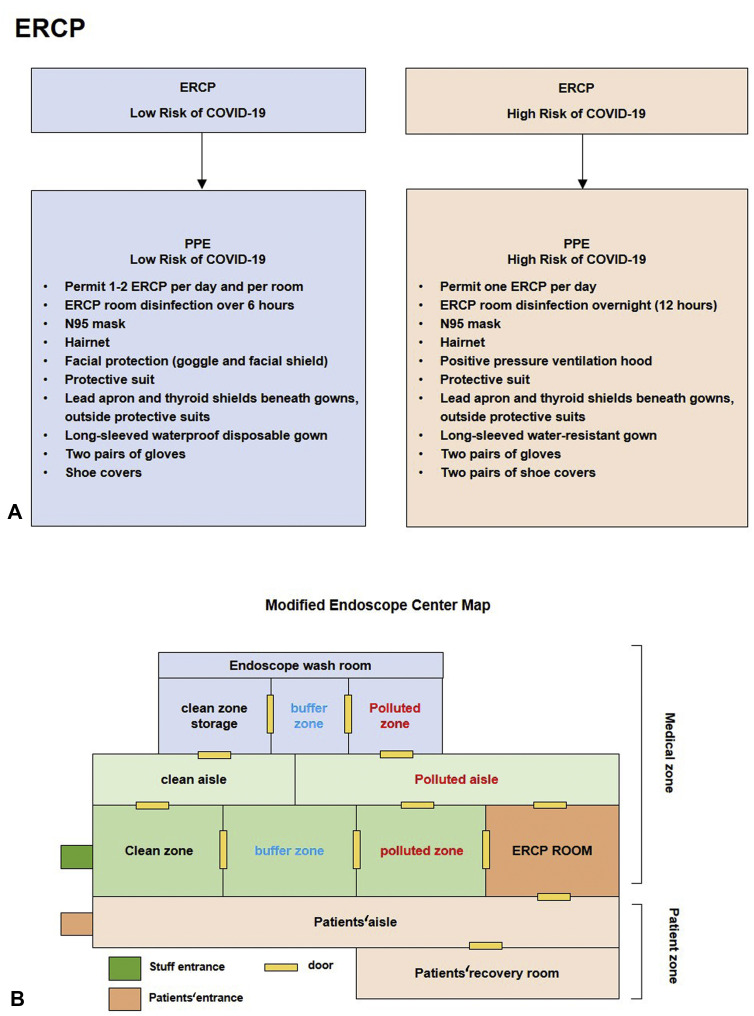

Figure 2.

ERCP and endoscopic center management. PPE, Personal protective equipment.

Figure 3.

Personal protective equipment of ERCP for high-risk patients. A, N95 mask, disposable hairnet, goggles, protective suit, 1 pair of gloves, 2 pairs of shoe covers. B, Lead apron and thyroid shields. C, Positive pressure ventilation hood. D, Long-sleeved waterproof disposable gown, another pair of gloves. E, Disposable sheet isolates between endoscopist and patient.

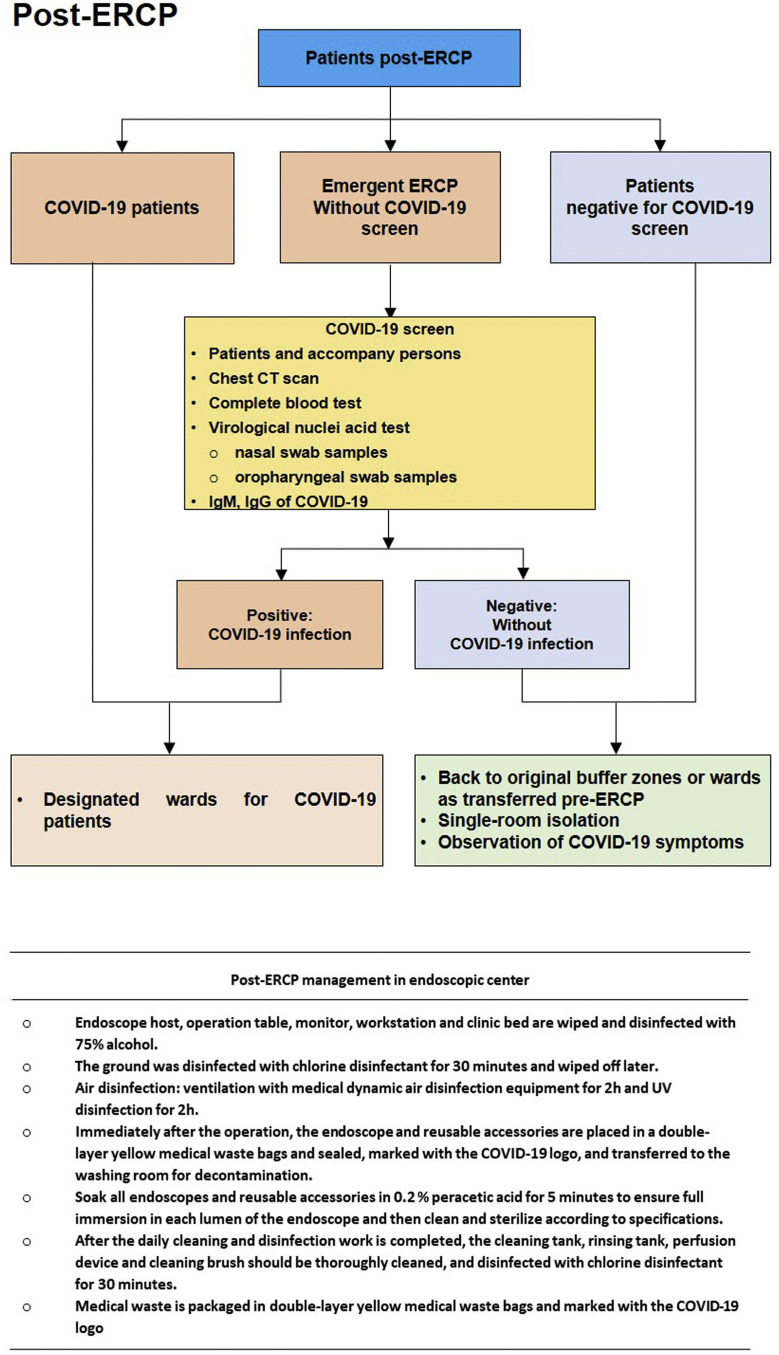

Figure 4.

Post-ERCP management.

Patients with acute obstructive cholangitis, aggravated bile duct obstruction (rapid increase in serum total bilirubin), acute biliary pancreatitis, and common bile duct gallstones with fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice underwent ERCP during the outbreak. COVID-19 screening examinations, including chest CT scans, complete blood tests, virologic nuclei acid polymerase chain reaction tests (nasal and oropharyngeal swab samples), and COVID-19 IgM/IgG determinations, were mandatory for all patients and for the persons accompanying those patients before ERCP, except for emergent cases. COVID-19–positive patients were admitted to designated wards. Other patients negative to COVID-19 infection spent 6 days of observation and preparation to transfer from 2 buffer zone wards (with 3 days of observation per ward) to GI department wards. Patients with COVID-19–related symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea, were kept under observation during the whole hospitalization, and COVID-19 screenings were considered once these alerting symptoms occurred. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, and waiver of informed consent was obtained (ID: WDRY2020-K075). All ERCPs were performed with the patient under conscious sedation with propofol and pethidine, and the patient was monitored by an anesthesiologist or endoscopist during the procedures.

After ERCP, COVID-19 patients returned to their designated wards, and uninfected patients were admitted back to the buffer zone or GI wards for further treatment and observation.

During the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, from February 1 to March 31, 31 ERCPs were performed for hospitalized patients admitted to Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University. The median age of the patients was 61 years (range, 40–84 years), and the majority were men (19 M:12 F). Most patients had comorbidities, and ≤41.9% of patients had hypertension. Anorexia (n = 29, 93.4%), fatigue (n = 29, 93.4%), and jaundice (n = 23, 74.2%) were the most common signs and symptoms. A total of 19.4% of patients (n = 6) had fever, and 35.5% (n = 11) had abdominal pain. The indications that necessitated ERCP included common bile duct gallstones (n = 15, 48.4%), acute biliary pancreatitis (n = 5, 16.1%), and carcinoma: cholangiocarcinoma (n = 8, 25.8%), ampullary cancer (n = 1, 3.2%), and duodenal papillary carcinoma (n = 2, 6.5%). Most patients (n = 21, 67.7%) underwent COVID-19 screening and then were admitted to wards by transfer from buffer zones to the GI department, whereas 32.3% of patients (n = 10) finished the screening after ERCP for emergent situations, including acute obstructive cholangitis and acute biliary pancreatitis (n = 5, 16.1%).

One patient who underwent emergent ERCP had a positive test result to COVID-19 nuclei acid in oropharyngeal swab samples taken right before the procedure. This patient was later confirmed to be an asymptomatic carrier of COVID-19. At the time the manuscript for this article was submitted, none of the other patients, their accompanying persons, or healthcare workers in our endoscopy center were reported to have the COVID-19 infection.

In the current new era of the COVID-19 outbreak and rapidly evolving epidemiologic information, hospitals have become one of the highest-risk places for both healthcare personnel and patients. With the dramatic development of this pandemic, the risk of aerosol-generating medical procedures gained extensive attention, especially for upper endoscopic procedures, including EGD, ERCP, and EUS, which carry the highest risk of exposure to aerosols.

Current guidelines and consensus recommendations advise that patient treatment should be based on a risk assessment of COVID-19 infection, which includes the patient’s exposure history (if the patient stayed in a high-risk area during the previous 14 days and had contact with an infected person) and typical symptoms regarding fever, cough, breathlessness, and diarrhea. Personal protective equipment was suggested to be provided accordingly.5 However, given that atypical symptoms without fever and respiratory presentations and current community transmission from asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 have already been documented (and false-negative results of virologic tests in some cases), it is challenging to identify all COVID-19 patients before ERCP procedures. Furthermore, for patients who need urgent ERCP, fever, abdominal pain, anorexia, and diarrhea are commonly seen and greatly increase the complexity of differential diagnosis. Therefore, in the standard operating procedure of our ERCP team, we regarded all new patients as potential COVID-19 candidates regardless of whether the patients were considered to be at low or high risk for COVID-19.

Although all patients underwent screening for COVID-19 before ERCP, some patients with emergent conditions could not wait for the results. In these patients, samples were taken for virus screening right before the procedure. It is important to differentiate community infection from nosocomial infection of the virus. One COVID-19 patient was identified in the first buffer zone ward after the ERCP procedure and was confirmed as having a community infection. Our measurements successfully identified this infected patient and prevented risky transmission. By the date of this article submission, no other patients, accompanying persons, or medical workers in our endoscopic center were reported or received diagnoses of COVID-19 infection.

In conclusion, our measures guaranteed that all healthcare workers in our endoscopy center, patients, and accompanying persons could avoid COVID-19 infection and that virus-infected patients could be identified during the procedure. Our experiences and measures for ERCP could help others establish optimal measures or standard operating procedures to avoid further unrecognized spread of the disease.

Disclosure

All authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Footnotes

Drs An, Huang, and Wan contributed equally and are joint first authors.

Supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81672387 to Yu Honggang) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81302131 to Ping An).

References

- 1.Repici A, Maselli R, Colombo M, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. Epub 2020 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Soetikno R, Teoh AY, Kaltenbach T, et al. Considerations in performing endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastrointest Endosc. Epub 2020 Mar 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.The National Health and Health Commission of China. http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-02/02/c_76098.htm Available at:

- 4.Beilenhoff U., Biering H., Blum R. Reprocessing of flexible endoscopes and endoscopic accessories used in gastrointestinal endoscopy: position statement of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (ESGENA) - Update 2018. Endoscopy. 2018;50:1205–1234. doi: 10.1055/a-0759-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; Stockholm, Sweden: 2020. Personal protective equipment (PPE) needs in healthcare settings for the care of patients with suspected or confirmed novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 2020. [Google Scholar]