Highlights

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed a significant strain on the United States health care system.

-

•

Healthcare workers are rapidly altering their professional responsibilities to help meet hospital needs.

-

•

Surgeons have witnessed a dramatic change in their practices with rapidly decreasing elective surgery.

-

•

Surgical leaders should develop a framework to help make decisions around elective surgery as information is evolving.

1. Elective surgery in the time of COVID-19

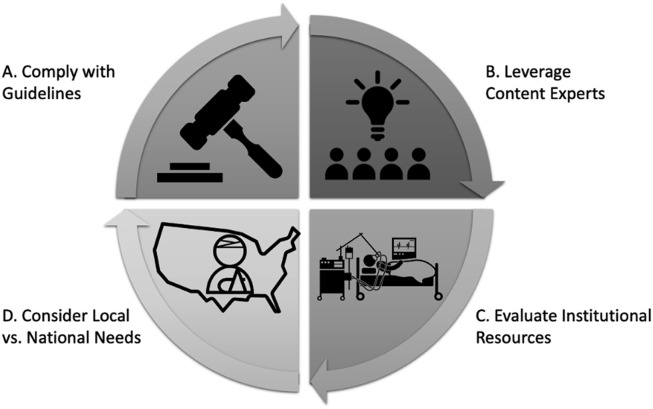

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has placed a significant strain on the United States health care system, and frontline healthcare workers are rapidly altering their professional responsibilities to help meet hospital needs. In an effort to decrease disease transmission and conserve personal protective equipment (PPE), and as a result of widespread recommendations, surgeons have witnessed one of the most dramatic changes in their practices with rapidly decreasing numbers of elective surgeries. General surgeons, in particular, are uniquely affected due to the wide variety of procedures they perform, many of which are conducted routinely in the outpatient setting. Interpreting the meaning of “elective” and balancing this definition with the health of the patient can become a challenge for even the most experienced surgeons. Fortunately, many groups, ranging from hospital boards to national societies, have weighed in on how to approach elective procedures. However, with so many federal and state orders, along with numerous societal recommendations, surgeons and hospital leadership are left with little guidance on how to interpret quickly evolving and sometimes conflicting information. As such we herein provide a brief review of publicly available federal, state, and general surgery society statements on elective surgery during the COVID-19 outbreak. We conclude by providing a framework (Fig. 1 ) for interpreting these legislative orders and societal guidelines amidst turbulent times and rapidly evolving information.

Fig. 1.

Framework for evaluating guidelines for elective surgery during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic

NOTES. Framework for establishing elective surgery guidelines during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic – as this is a rapidly evolving situation, stakeholders should repeatedly cycle through A-D as new information becomes available. A. Leaders should review and evaluate national, state, local, and society guidelines so that their surgeons and institutions are compliant. B. Leaders should leverage content experts within their institution such as disease content experts (e.g. surgeon), nurses, administrators, ethicist, and supply chain managers to help inform local guidelines and recommendations. C. All stakeholders should evaluate current and projected resources including workforce, PPE, and medical equipment (e.g. ventilators) and weigh availability versus disease burden D. Stakeholders should consider their patients immediate needs while being sensitive to national needs.

2. Federal, state, and societal guidelines

As the Coronavirus outbreak was well into its evolution during March of 2020, concerns about conserving resources and PPE led to calls for delaying non-urgent services. As such, on March 18 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that all elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures be delayed. The announcement by CMS came as a recommendation that provided hospitals and clinicians specific examples to guide whether or not to postpone a given surgery.1 Individual states have also contributed to the conversation on elective surgery. At the time of writing, 33 states (66%) have issued guidance in the form of either a mandate or recommendation on limiting elective surgeries.2 At the time of our final review (March 24th 5:00pm EDT) announcement dates ranged from March 15th to March 23rd. Ten of the 33 states listed an end date ranging from April 13th to June 19th.

Of note, the direction provided by states varies. Specifically, some states such as Massachusetts have defined nonessential, elective invasive procedures as procedures that are scheduled in advance because the procedure does not involve a medical emergency and provide a list of examples.3 Other states, such as Alaska, have acknowledged the difficulty of applying a blanket statement to define “elective surgery” for state-wide guidelines, and have chosen to keep their guidance brief while urging individual hospital systems to create their own frameworks.4 The result of such vague guidance has been a concern among general surgeons who, in turn, are required to interpret and apply medical recommendations often published by non-medical or non-surgical professionals. Similar to CMS, nearly all states that provided a statement on elective surgery did so only as guidelines or recommendations. One exception was Maryland that stated, “The secretary is authorized and ordered to take actions to control, restrict, and regulate the use of health care facilities for the performance of elective medical procedures …”. Violation of Maryland’s order is punishable up to one year imprisonment or a fine up to $5000 or both.5

In an effort to help clarify the ambiguity surrounding federal and state guidelines relative to elective surgery, several professional societies have put out their own guidelines, often providing disease specific guidance. For instance, the American College of Surgeons provides subspecialty specific guidelines ranging from cancer surgery to neurosurgery and urology.6 Some of these guidelines issue overarching principles such as considering nonoperative management whenever clinically appropriate, whereas other guidelines provide disease specific consideration, as in the case of emergency general surgery. Considerations for cancer surgery, in particular, have been debated due to balancing the elective nature of most operations with the risk of disease progression. As such, the Society of Surgical Oncologist has developed disease-site specific management resources that takes into account cancer stage.7

3. Framework for local decisions making

As the COVID-19 outbreak quickly spreads across the country, surgeons and hospital leaders are left trying to consume, interpret, and implement ever-changing recommendations for elective surgery. Making well informed decisions will necessitate surgeon leaders to establish multi-disciplinary teams that can absorb information in real-time and provide the best local recommendations while being sensitive to national priorities (Fig. 1). First, hospital leadership and surgery department chairs should assure that their respective departments are in compliance with both federal and state recommendations when available. Although much of the existing legislation lacks detail on enforceability, the ultimate price may come in the form of public opinion. Surgeons may not want to find themselves explaining to their community why they continued to perform elective operations while their collogues struggled to find PPE.

Surgical department chairs should also convene content experts including, but not limited to surgeons, nurses, administrators, resource managers, and ethicists. Expert panels should be tasked with establishing and updating elective surgery guidelines. Experts should consider and balance national, state, and local resources and priorities. For example, there are areas in the country that have been largely unaffected by the pandemic. In this instance, leaders in less affected areas must weigh the utilization of PPE for elective procedures against the demand for goods and services in other, heavily affected parts of the country. Additionally, special consideration should be given to the tradeoff of resource utilization between surgery and non-operative management. For example, in the management of acute appendicitis one may elect non-operative management to free up resources. However, unintended consequences may include utilization of hospital beds and resources for intravenous antibiotic administration. In these instances, one must consider local capacity relative to the trajectory of the COVID-19 disease burden to guide recommendations. As both capacity and disease burden evolve, so too will recommendations.

Beyond the walls of large medical centers, leaders of free standing ambulatory and outpatient surgery centers should also be sensitive to developing concerns. Understandably, these surgical centers may be hesitant to postpone elective surgery as they are dependent on these services as a source of revenue.8 Furthermore, the American College of Surgeons guidelines have suggested that some lower acuity surgery may be performed at ambulatory surgical centers.9 However, leaders of these free standing centers should work closely with their local departments of public health to anticipate future needs and resources allocation. In addition, ambulatory centers may be necessary to address overflow problems at the main hospital due to the COVID-19 surge.10 Cutting back on elective procedures at ambulatory centers may be crucial to slowing the spread of SARS-CoV-2, as well as make capacity, staff, and equipment available to address COVID-19 as the outbreak spreads.

4. Conclusion

It is incumbent on hospital leadership and department/division leaders to adapt their policies to the dynamic local environment--taking into account current and projected PPE, staffing, beds, and equipment needs. A hospital may be compliant based on state and national guidelines while following society recommendations; however, these guidelines may be inappropriate for a strained hospital system. Surgeon leaders need to synthesize national, state and local data to make the best decisions for their patients locally, while being sensitive to the broader national implications.

Disclosures

Dr. Janis receives royalties from Thieme Publishing, otherwise the authors have no conflicts of interest pertaining to the work herein.

Funding

Dr. Diaz receives funding from the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation Clinician Scholars Program and salary support from the Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations during the time of this study.

Disclaimer

This does not necessarily represent the views of the United States Government or Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.CMS releases recommendations on adult elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures during COVID-19 response. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental CMS Available from:

- 2.State guidance on elective surgeries available from. https://www.ascassociation.org/covid-19-state

- 3.The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Elective procedures order. https://www.mass.gov/doc/march-15-2020-elective-procedures-order Available from:

- 4.Dunleavy M. COVID-19 health mandate. http://dhss.alaska.gov/News/Documents/press/2020/SOA_03192020_HealthMandate005_ElectiveMedProcedures.pdf Available from:

- 5.Neall R.R. Directive and order regarding various healthcare matters. https://governor.maryland.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/03.23.2020-Sec-Neall-Healthcare-Matters-Order.pdf Available from:

- 6.COVID-19: elective case triage guidelines for surgical care. American College of surgeons. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case Available from:

- 7.COVID-19 resources. Society of surgical oncology. https://www.surgonc.org/resources/covid-19-resources/ Available from:

- 8.Statement from the ambulatory surgery center association regarding elective surgery and COVID-19. https://www.ascassociation.org/asca/resourcecenter/latestnewsresourcecenter/covid-19/covid-19-statement Available from:

- 9.COVID-19: guidance for triage of non-emergent surgical procedures. American College of surgeons. 2020. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/triage Available from:

- 10.Szabo CA Liz. The nation’s 5,000 outpatient surgery centers could help with the COVID-19 overflow. Kaiser health news. 2020. https://khn.org/news/the-nations-5000-outpatient-surgery-centers-could-help-with-the-covid-19-overflow/ Available from: