Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the effects of pharmacologic treatment of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) on neurodevelopmental outcome from a randomized controlled trial.

Study design:

Eight sites enrolled 116 full-term newborn infants with NAS born to mothers maintained on methadone or buprenorphine into a randomized trial of morphine vs methadone. Ninety-nine (85%) were evaluated at hospital discharge using the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS). At 18-months, 83 of 99 (83.8%) were evaluated with the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-Third Edition (Bayley-III) and 77 of 99 (77.7%) with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).

Results:

Primary analyses showed no significant differences between treatment groups on the NNNS, Bayley-III, or CBCL. However in post-hoc analyses, we found differences by atypical NNNS profile on the CBCL. Infants receiving adjunctive phenobarbital had lower Bayley-III scores and more behavior problems on the CBCL. In adjusted analyses, internalizing and total behavior problems were associated with use of phenobarbital (P=.03; P=.04), maternal psychological distress (measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory) (both P<.01), and infant medical problems (both P = .02). Externalizing problems were associated with maternal psychological distress (P<.01) and continued maternal substance use (P<.01).

Conclusions:

Infants treated with either morphine or methadone had similar short and longer-term neurobehavioral outcomes. Neurodevelopmental outcome may be related to the need for phenobarbital, overall health of the infant, and postnatal caregiving environment.

Trial registration

Keywords: Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, opioid, neurodevelopmental outcome

In the past two decades, the number of newborn infants exposed to opioids in utero has increased by 333%, which translates to approximately one infant born every 15 minutes in the United States (1). Fifty to eighty percent of newborn infants exposed to opioids develop Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) (2-4). Although the approach to infants with NAS has primarily focused on non-pharmacologic care, many infants with significant NAS will still require pharmacological intervention. Morphine and methadone are the drugs most commonly used to treat NAS. Little is known about the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with prenatal opioid exposure let alone those who receive pharmacological treatment for NAS (5).

We previously reported a multisite, blinded, randomized controlled trial comparing morphine with methadone for the treatment of infants with NAS (6). Methadone was associated with significant reductions in the length of hospital stay, length of stay from NAS, and length of treatment. The present study expanded the measurements of neonatal safety and clinical effectiveness to include both short-term and long-term neurobehavioral outcomes. First, we analyzed neurobehavioral performance on the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) at hospital discharge (when all treatment had been discontinued) in infants randomized to receive morphine or methadone (7). Then we performed an 18-month assessment of cognitive, language, and motor outcomes using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-Third Edition (Bayley-III) and behavior problems using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (8,9). Our goal was to compare the impact of treatment with morphine or methadone on short- and longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

METHODS

The study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01958476) was conducted at 8 sites (Tufts Medical Center - Boston, MA, Baystate Children’s Hospital - Springfield, MA, Boston Medical Center - Boston, MA, Maine Medical Center - Portland, ME, UF Health - Jacksonville, FL, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center - Pittsburgh, PA, Vanderbilt University Medical Center - Nashville, TN, Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island - Providence, RI). Mothers receiving prenatal care who were treated with buprenorphine (33.6%) or methadone (62.9%) for an opioid use disorder or chronic pain (3.5%) were eligible for the study. A total of 117 infants were randomized to receive methadone or morphine from 2/9/2014, to 3/5/2017. Data were available for 116 full-term infants with NAS who required pharmacologic treatment (mean gestational age: 39.1 weeks, SD 1.1; mean birth weight: 3157 grams, SD 486; males, 58 (50%)) (6). Infants in the study who exceeded a predetermined opioid dose received phenobarbital. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site and informed consent was obtained by study investigators.

Outcome Measures

Certified examiners performed neurobehavioral assessments at hospital discharge on 99/116 (85%) infants using the NNNS. The NNNS is a comprehensive assessment of neonatal neurobehavior that examines neurological integrity, behavioral function and signs of stress (10). In research, the NNNS is used to assess high risk newborn infants including those with prenatal opioid and other illicit drug exposure and correlates with long-term neurodevelopmental outcome (11-14).

At approximately 18 months of age, the Bayley-III was administered by certified examiners to 94 (81%) infants. The Bayley-III includes cognitive, language and motor composite scores, receptive and expressive communication, and fine and gross motor subscale scores that are corrected for prematurity and compared with a normative control sample. The CBCL was completed for 85 (73%) infants by the mother or primary caregiver and is a measure of behavioral problems identified in the infant. The checklist consists of 100 statements about the child's behavior and responses are recorded on a scale: 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true. Items are grouped into syndrome scales (e.g. aggressive behavior) that are further combined into internalizing and externalizing problem scales. A total problem score from all questions is also derived. For each syndrome scale, problem scale and the total score, there are norms for normal, borderline, or clinically significant scores.

At the 18-month follow-up, we also administered questionnaires to quantify caregiver and infant characteristics. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) is a self-report questionnaire that assesses psychological distress. The global severity index (GSI) is an indicator of the respondent’s distress level that combines a number of symptoms and distress intensity (15). We also measured involvement in early intervention services (occupational therapy, speech therapy, behavioral therapy), household composition, primary language spoken at home, infant medical problems (collected at follow-up including problems with speech, vision, behavior, viral infections, feeding disorders, and any chronic health conditions such as asthma, heart conditions, or allergies), infant health and physical growth, medications the infant was taking, number of emergency room visits since birth, maternal postnatal substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs), caregiver abuse (emotional, physical or sexual), out-of-home placement, and the involvement of the Department of Child and Family Services. These characteristics were all examined for inclusion in statistical analyses.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Caregiver and infant characteristics at birth and follow-up were described in the morphine and methadone groups. Means and standard deviations were used for continuous measures. Categorical variables were expressed as observed counts and percentages. The NNNS was analyzed using latent profile analysis (LPA) which grouped infants into mutually exclusive categories using 12 summary scores. Membership for categorical latent profiles that represent heterogeneous subgroups was inferred from the 12 NNNS variables. LPA models with different numbers of profiles were fitted. Determination of the best model fit was assessed via Bayesian information criteria (BIC) adjusted for sample size, whereby the smallest BIC value indicates the best fit as well as minimization of cross classification probabilities.

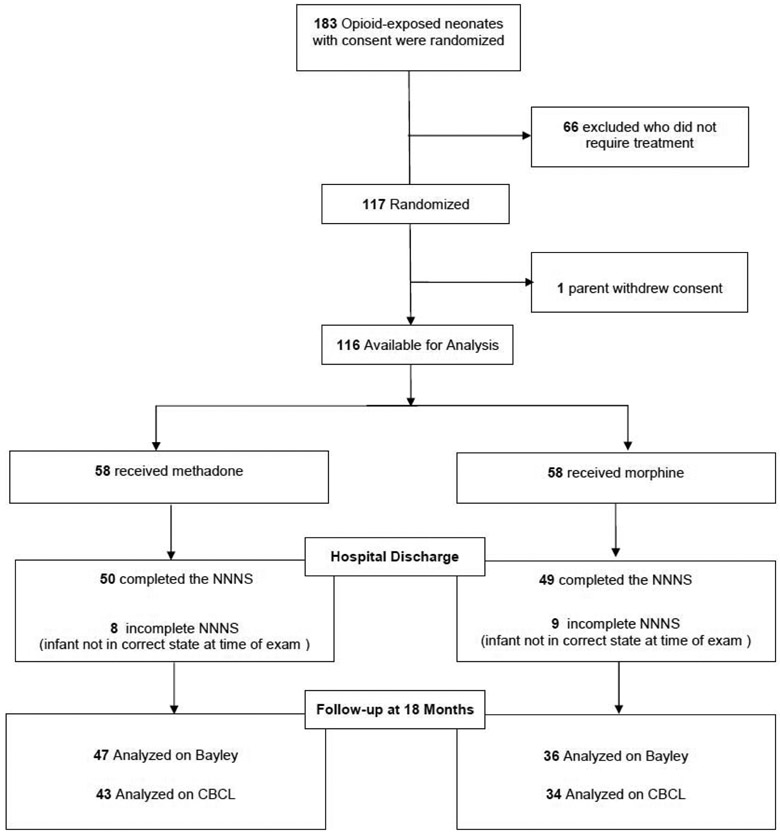

Linear regression was used to test for the effects of treatment group on infants with a neurobehavioral assessment at hospital discharge and Bayley-III (n=83) or CBCL (n=77) scores at follow-up (Figure 1) adjusting for site, maternal opioid exposure, need for phenobarbital at discharge, maternal psychological distress (GSI), early intervention services, infant medical problems, maternal postnatal substance use, involvement of the Department of Child and Family Services, and sex. Analyses were performed using SPSS v24 and MPLUS v8.1.

Figure 1.

Participant flow at follow-up for Clinical Trial NCT01958476

RESULTS

Ninety-nine infants (85%) were evaluated at hospital discharge using the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS). Caregiver and neonatal characteristics were similar between groups. The number of mothers reporting that they smoked 5 or more cigarettes per day was higher in the methadone group and more infants in the morphine group were discharged on phenobarbital (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 1.

Caregiver and Infant Characteristics at Birth

| N (%) or Mean (SD) | Methadone (n = 50 ) |

Morphine (n = 49) |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Characteristics | ||

| Opioid | ||

| Buprenorphine | 19 (38.0%) | 15 (30.6%) |

| Methadone | 31 (62.0%) | 30 (61.2%) |

| Prescription opioids for pain | 0 | 4 (8.2%) |

| Smoked >5 cigarettes per day | 29 (63.0%) | 11 (25.6%) |

| Psychiatric diagnoses | 15 (30.0%) | 12 (24.5%) |

| Psychiatric medication during pregnancy | 17 (35.4%) | 13 (26.5%) |

| Neonatal Characteristics | ||

| Sex (male) | 24 (48.0%) | 24 (49.0%) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.2 (1.2) | 39.0 (1.1) |

| Birth weight (g) | 3202 (494) | 3107 (490) |

| Birth length (cm) | 49.6 (2.3) | 49.2 (3.0) |

| Head circumference (cm) | 34.0 (1.7) | 33.7 (1.8) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 3 (6.0%) | 5 (10.2%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 39 (78.0%) | 35 (71.4%) |

| Other | 11 (22.0%) | 14 (28.6%) |

| Age at treatment (days) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.6) |

| Phenobarbital at discharge | 5 (10.0%) | 14 (28.6%) |

Of 116 infants, 94 (81%) attended the follow-up visit. Of those, 15 (12.9%) of infants treated with morphine were lost to follow-up and 7 (6.0%) infants treated with methadone (p=0.11). There were no differences between those followed vs not followed on any of the caregiver or neonatal characteristics with the exception of infant sex. More boys were lost to follow-up than girls (p=.006). At 18-months, 83 infants were evaluated with the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-Third Edition (Bayley-III) and 77 with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). At the 18-month follow-up, caregiver and infant characteristics were similar between groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Caregiver and Infant Characteristics at 18-Month Follow-up

| N % or Mean (SD) | Methadone (n = 47) |

Morphine (n = 36) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Characteristics | |||

| Receiving Methadone or Buprenorphine | 33 (76.7%) | 22 (66.7%) | 0.33 |

| Postnatal substance use (total number used) | 2.3 (1.7) | 1.7 (1.0) | 0.08 |

| Caregiver report of abuse | 6 (14.0%) | 3 (9.1%) | 0.52 |

| Psychological distress (BSI total) | 0.53 (0.60) | 0.53 (0.63) | 0.97 |

| Infant Characteristics | |||

| Sex (male) | 24 (51.1%) | 22 (61.0%) | 0.36 |

| Weight (kg) | 11.7 (2.0) | 11.5 (2.0) | 0.64 |

| Length (cm) | 81.9 (4.7) | 81.7 (5.2) | 0.87 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 47.8 (2.4) | 48.2 (2.3) | 0.55 |

| Phenobarbital at discharge | 5 (10.6%) | 11 (30.6%) | 0.02 |

| Early Intervention Services | 19 (43.2%) | 15 (45.5%) | 0.84 |

| Any medical problem | 25 (65.8%) | 20 (60.6%) | 0.65 |

| CPS involvement | 27 (60%) | 16 (47.1%) | 0.25 |

| Out-of-home placement | 8 (17.8%) | 8 (23.5%) | 0.53 |

NNNS summary scores did not differ between treatment groups at discharge (Table 3; available at www.jpeds.com). The three profile LPA model suggested the best solution. Profile 3 is an atypical profile and included 24 (24.2%) infants (Figure 2). Infants with this profile: 1) required substantive handling, 2) had poor regulation, 3) had higher arousal and excitability, 4) were hypertonic, 5) had poor quality of movement, and 6) had more signs of stress compared with infants with the other profiles. There were no differences between treatment groups in the number of infants who had typical versus atypical profiles on the NNNS. Twelve infants in the morphine group and 12 in the methadone group had atypical NNNS.

Table 3.

Neurodevelopment at Discharge

| Mean (SD) | Methadone (n = 50) |

Morphine (n = 49) |

95% CI (difference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NNNS summary scores | |||

| Attention | 5.16 (1.69) | 4.91 (1.34) | −0.44, 0.95 |

| Handling | 0.47 (0.32) | 0.39 (0.32) | −0.06, 0.21 |

| Regulation | 5.24 (0.93) | 5.03 (0.86) | −0.15, 0.57 |

| Arousal | 4.23 (0.80) | 4.29 (0.85) | −0.39, 0.27 |

| Excitability | 4.16 (2.72) | 4.39 (2.83) | −1.33, 0.89 |

| Lethargy | 3.76 (2.10) | 3.78 (2.14) | −0.86, 0.83 |

| Hypertonicity | 0.52 (1.15) | 0.59 (1.00) | −0.50, 0.36 |

| Hypotonicity | 0.24 (0.48) | 0.14 (0.41) | −0.08, 0.27 |

| Nonoptimal Reflexes | 4.38 (2.34) | 4.91 (2.07) | −1.43, 0.36 |

| Asymmetric Reflexes | 0.55 (1.21) | 0.53 (1.00) | −0.43, 0.47 |

| Quality of Movement | 4.32 (0.83) | 4.40 (0.81) | −0.41, 0.24 |

| Stress Abstinence | 0.14 (0.08) | 0.14 (0.08) | −0.04, 0.03 |

Figure 2.

NNNS Profiles at Hospital Discharge

At 18 months, there were no differences between treatment groups on the Bayley-III composites (mean postnatal age at examination: 19.5 ± 3.2 months) or CBCL scores (mean postnatal age at examination: 19.7 ± 3.2 months) (Table 4). There were no differences between infants with typical versus atypical profiles on the NNNS on all Bayley-III composites. However, infants with the atypical NNNS profile had more externalizing, internalizing and total behavior problems on the CBCL than infants with typical profiles (Table 4). Infants discharged on phenobarbital had lower cognitive, language and motor Bayley-III composite scores and higher internalizing and total problem CBCL scores (Table 4).

Table 4.

Neurodevelopment at 18 Month Follow-up

| Mean (SD) | Methadone | Morphine | 95% CI (difference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayley-III | n=47 | n=36 | |

| Cognitive Composite | 100.1 (21.4) | 98.1 (17.2) | −6.61, 10.76 |

| Language Composite | 96.0 (16.9) | 94.2 (18.2) | −5.98, 9.41 |

| Motor Composite | 103.4 (17.2) | 99.1 (17.2) | −3.19, 11.93 |

| Child Behavior Checklist | n=43 | n=34 | |

| Externalizing Problems | 49.3 (11.7) | 49.0 (10.2) | −4.77, 5.34 |

| Internalizing Problems | 45.5 (11.6) | 45.7 (11.3) | −5.43, 5.01 |

| Total Problems | 48.5 (12.1) | 48.5 (11.1) | −5.34, 5.31 |

| Mean (SD) | Atypical Profile | Typical Profiles | 95% CI (difference) |

| Bayley-III | n=21 | n=62 | |

| Cognitive Composite | 95.5 (19.5) | 100.5 (19.7) | −4.83, 14.88 |

| Language Composite | 93.7 (17.1) | 95.7 (17.6) | −6.79, 10.75 |

| Motor Composite | 101.9 (19.1) | 101.4 (16.7) | −9.12, 8.25 |

| Child Behavior Checklist | n=18 | n=59 | |

| Externalizing Problems | 54.2 (11.5) | 47.6 (10.4) | −12.31, −0.84 |

| Internalizing Problems | 51.7 (13.7) | 43.7 (9.9) | −13.89, −2.20 |

| Total Problems | 55.2 (13.4) | 46.4 (10.2) | −14.70, −2.87 |

| Mean (SD) | Phenobarbital at discharge |

No phenobarbital at discharge |

95% CI (difference) |

| Bayley-III | n=16 | n=67 | |

| Cognitive Composite | 89.1 (15.2) | 101.7 (19.9) | 2.02, 23.16 |

| Language Composite | 83.5 (14.8) | 98.0 (16.9) | 5.35, 23.62 |

| Motor Composite | 93.1 (9.87) | 103.5 (18.0) | 1.12, 19.71 |

| Child Behavior Checklist | n=16 | n=61 | |

| Externalizing Problems | 53.5 (11.2) | 48.0 (10.7) | −11.57, 0.54 |

| Internalizing Problems | 51.0 (15.1) | 44.1 (9.8) | −13.06, −0.67 |

| Total Problems | 54.0 (14.6) | 47.1 (10.3) | −13.27, −0.63 |

In post-hoc exploratory analyses, 12 infants (26.1%) in the methadone group and 12 infants in the morphine group (33.3%) scored <85 (1SD) on the Bayley Language Composite (P= .47). There were covariate effects on the Bayley and the CBCL (Table 5; available at www.jpeds.com). Males had lower Bayley Language Composite scores than females (β=−.32; P<.01). On the CBCL, internalizing behavior problems were associated with the use of phenobarbital at discharge (β=.27; P=.03), more maternal psychological distress (β=.30; P <.01), and more infant medical problems (β=.27; P=.02). Externalizing behavior problems were associated with maternal psychological distress (β=.41, P<.01) and maternal postnatal substance use (β=.29; P<.01). Total behavioral problems were associated with the use of phenobarbital at discharge (β=.24; P=.04), maternal psychological distress (β=.38; P <.01), and more infant medical problems (β=.27; P=.02).

Table 5.

Bayley-III and CBCL Covariate Effects

| Bayley-III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B* | SE B | β* | P | |

| Language Composite | ||||

| Male Sex | −11.3 | 5.1 | −.32 | .03 |

| CBCL | ||||

| B* | SE B | β* | P | |

| Internalizing Behavior | ||||

| Phenobarbital at Discharge | 7.5 | 3.3 | .27 | .03 |

| Maternal Psychological Distress | 5.3 | 2.1 | .30 | <.01 |

| Child Medical Problems | 2.2 | 0.9 | .27 | .02 |

| Externalizing Behavior | ||||

| Maternal Psychological Distress | 6.8 | 1.8 | .41 | <.01 |

| Maternal Postnatal Substance Use | 2.0 | 0.8 | .29 | <.01 |

| Total Problems | ||||

| Phenobarbital at Discharge | 6.5 | 3.1 | .24 | .04 |

| Maternal Psychological Distress | 6.7 | 1.9 | .38 | <.01 |

| Child Medical Problems | 2.2 | 0.9 | .27 | .02 |

DISCUSSION

The increasing rates of NAS across the United States have highlighted the need for an evidence-based treatment approach. Currently no universally accepted standards exist for pharmacologic treatment, and most centers depend on dosing strategies derived from pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic data or center experience (16,17). In our multicenter randomized control trial to examine the safety and efficacy of the most common drugs used to treat NAS, we found better short-term NAS outcomes including length of hospital stay, length of hospital stay from NAS, and length of treatment with methadone compared with morphine (6). Here, we expand the scope of our previous findings by reporting the impact of these drugs on short- and long-term neurobehavioral outcomes. Although there were no significant differences between treatment groups, 24.2% of the infants showed the atypical NNNS profile. We found differences by atypical NNNS profile on the CBCL. These findings are consistent with previous studies where this specific atypical NNNS profile has been related to long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes including behavior as assessed using the CBCL and intelligence quotients through 4.5 years of age in infants with prenatal drug exposure (14) This suggests that these profiles could have clinical utility as they highlight unique neurobehavioral targets for intervention that can be included as part of discharge planning, medical and neurodevelopmental follow-up, and early intervention programs.

At 18 months we found no differences on the Bayley-III or CBCL mean scores between treatment groups. Bayley-III normative data was established using a sample collected in the United States and is stratified on key demographic variables with 16% of the original population having scores below 85 (16). However, in our sample 33% of infants who had been treated for NAS with morphine scored <85 on the Bayley Language Composite, more than twice that in the normative sample, suggesting an increased risk for language delays that could benefit from referral to early intervention services at the time of initial hospital discharge and more careful neurodevelopmental follow-up. Previous studies have found that children with NAS performed lower than the normative sample on the Bayley-III (18). Clinical outcomes that differentiate level of function relative to a normative sample are important as it may be difficult to distinguish between change due to development, treatment affect, or disease-related factors (19-22). Males may also be at higher risk for lower language scores than females.

We also identified covariate effects on the CBCL. Behavioral problems were related to the use of phenobarbital, especially being discharged on the drug. The use of phenobarbital was permitted when a pre-determined maximum opioid dose did not adequately control withdrawal. Although phenobarbital was not considered a study drug and the total duration of use was not tracked, these behavioral problems could be related to NAS severity or potential toxicity of phenobarbital. Many infants are discharged to home on this drug and many physicians and parents may elect to maintain the treatment for longer periods of time. The CBCL findings suggest that it may be important to stop the phenobarbital as soon as possible. In addition, other elements in the postnatal caregiving environment including infant medical problems and maternal psychosocial factors (psychological distress and substance use) were important modifiers of neurobehavioral outcome. The critical role of the postnatal caregiving environment has been well described in other developmental outcome studies of children with prenatal drug exposure (23). Our findings suggest that with respect to NAS, the postnatal caregiving environment could play a significant role in contributing to neurobehavioral outcomes. Any newborn infant with significant enough signs to receive pharmacologic treatment could be particularly susceptible to early childhood behavioral problems and subsequent mental health disorders. Early intervention referral and ongoing psychological and social supports for the parents of these infants is needed.

Although the baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups appeared similar at 18 months, a reduced sample size of the follow-up cohort could limit power to detect possible effects or exaggerate other findings. In addition, our baseline sample was also limited to infants with NAS who all required treatment. It is important to note that the methadone used was specifically developed and compounded for this clinical trial to be preservative (alcohol) free. Commercially available methadone can have up to 15% alcohol as a preservative and could have other effects on neurobehavioral outcome. We also used a weight-and sign-based treatment protocol for NAS which permitted the use of phenobarbital when a pre-determined maximum opioid dose did not adequately control the signs of withdrawal. These approaches must be considered when altering practice guidelines and treating this vulnerable population.

Although infants treated for NAS with methadone or morphine showed similar short- and long-term neurobehavioral outcomes, it is essential to follow neurobehavioral outcomes in this population in order to fully understand the true impact of pharmacologic treatment or other practice changes in this high-risk population. At approximately 18 months, scores on the Bayley-III examinations indicated that these infants were at higher risk for language delays that may warrant early intervention referral. Finally, neurodevelopmental outcome of children who had NAS needs to be better understood in the context of being discharged on phenobarbital or other significant factors in the postnatal caregiving environment. This highlights the definitive need to provide ongoing support to these families once they are discharged from the hospital.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA032889 [to J.D. and B.M.]).

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- (NAS)

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

- (NNNS)

NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale

- (CBCL)

Child Behavior Checklist

- (Bayley-III)

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-Third Edition

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:845–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes AV, Atwood EC, Whalen B, Beliveau J, Jarvis JD, Matulis JC, et al. Rooming-in to treat neonatal abstinence syndrome: Improved family-centered care at lower cost. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko JY, Patrick SW, Tong VT, Patel R, Lind JN, Barfield WD. Incidence of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome - 28 States, 1999-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:799–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, Greene MF, Opioid Use in Pregnancy NAS, Childhood Outcomes Workshop Invited S. Opioid Use in Pregnancy, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, and Childhood Outcomes: Executive Summary of a Joint Workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the March of Dimes Foundation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:10–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conradt E, Flannery T, Aschner JL, Annett RD, Croen LA, Duarte CS, Friedman AM, Guille C, Hedderson MM, Hofheimer JA, Jones MR, Ladd-Acosta C, McGrath M, Moreland A, Neiderhiser JM, Nguyen RHN, Posner J, Ross JL, Savitz DA, Ondersma SJ, Lester. Prenatal Opioid Exposure: Neurodevelopmental Consequences and Future Research Priorities. Pediatrics. 2019. September;144: e20190128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis JM, Shenberger J, Terrin N, et al. Comparison of safety and efficacy of methadone vs morphine for treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:741–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lester BM, Tronick EZ, Brazelton TB. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale procedures. Pediatrics. 2004;113:641–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albers CA, Grieve AJ. Test Review: Bayley, N. Bayley scales of infant and toddler development– third edition. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. J Psychoed Assess. 2007;25:180–90 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Achenbach system of empirically based assessment In: Volkmar FR, editor. Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013. p. 31–9 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tronick EZ, Olson K, Rosenberg R, Bohne L, Lu J, Lester BM. Normative neurobehavioral performance of healthy infants on the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale. Pediatrics. 2004;113:676–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boukydis CF, Bigsby R, Lester BM. Clinical use of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale. Pediatrics. 2004;113:679–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coyle MG, Salisbury AL, Lester BM, Jones HE, Lin H, Graf-Rohrmeister K, et al. Neonatal neurobehavior effects following buprenorphine versus methadone exposure. Addiction. 2012;107 Suppl 1:63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiblawi ZN, Smith LM, Diaz SD, LaGasse LL, Derauf C, Newman E, et al. Prenatal methamphetamine exposure and neonatal and infant neurobehavioral outcome: results from the IDEAL study. Subst Abus. 2014;35:68–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Bann C, Lester B, Tronick E, Das A, Lagasse L, et al. Neonatal neurobehavior predicts medical and behavioral outcome. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e90–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derogatis LR. BSI 18, brief symptom inventory 18: Administration, scoring and procedures manual: NCS Pearson, Incorporated; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall ES, Meinzen-Derr J, Wexelblatt SL. Cohort analysis of a pharmacokinetic-modeled methadone weaning optimization for Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. J Pediatr. 2015;167:1221–5.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Grady MJ, Hopewell J, White MJ. Management of neonatal abstinence syndrome: a national survey and review of practice. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F249–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merhar SL, McAllister JM, Wedig-Stevie KE, Klein AC, Meinzen-Derr J, Poindexter BB. Retrospective review of neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Perinatol. 2018;38:587–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips D and Leiro B. Clinical Outcome Assessments: Use of Normative Data in a Pediatric Rare Disease. Value in Health. 2018;21:508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charnay AJ, Antisdel-Lomaglio JE, Zelko FA, Rand CM, Le M, Gordon SC, Vitez SF, Tse JW, Brogadir CD, Nelson MN, Berry-Kravis EM, Weese-Mayer DE. Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome: Neurocognition Already Reduced in Preschool-Aged Children. Chest. 2016;149:809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hicks MS, Sauve RS, Robertson CM, Joffe AR, Alton G, Creighton D, Ross DB, Rebeyka IM; Western Canadian Complex Pediatric Therapies Follow-up Group. Early childhood language outcomes after arterial switch operation: a prospective cohort study. Springerplus. 2016; 5:1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolwijk LJ, Lemmers PM, Harmsen M, Groenendaal F, de Vries LS, van der Zee DC, Benders MJ, van Herwaarden-Lindeboom MY. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes After Neonatal Surgery for Major Noncardiac Anomalies. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20151728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lester BM, Lagasse LL. Children of addicted women. J Addict Dis. 2010;29:259–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.