SUMMARY

Background

We examined the effectiveness of integrated stepped alcohol treatment (ISAT) on alcohol use and HIV outcomes among patients living with HIV (PLWH) and alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Methods

In this multi-site randomized trial conducted in five Veterans Affairs-based HIV clinics , we enrolled PLWH and AUD who were not otherwise receiving formal alcohol treatment. Using a web-based clinical trial management system, participants were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to receive ISAT or treatment as usual (TAU). ISAT involved: Step 1 - Addiction Physician Management (APM), Step 2- APM plus Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET), and Step 3 – Specialty referral. Participants were stepped up at weeks 4 and 12 if they exceeded a priori drinking criteria. Treatment as usual (TAU) involved referral. The primary outcome was drinks per week over the past 30 days at week 24 by Timeline Followback. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01410123.

Findings

Between January 28, 2013 and July 14, 2017, we randomized 128 participants to receive ISAT (n=63) and TAU (n=65). Fifty-two percent (30/57) ISAT participants advanced to Step 2 and 57% (17/30) to Step 3. Fifty one percent (32/63) in ISAT vs. 26% (17/65) in TAU received at least one alcohol medication (p=0·004). Both groups decreased alcohol consumption. At week 24 (primary outcome), we did not detect a difference between the ISAT and TAU groups in drinks per week (Least square mean (Lsmean) [SD]= 10·4 [16·5] vs. 15·6 [17·6]), adjusted mean difference [AMD] [95% CI]= −4·2 [−9·4, 0·9], p=0·11)

Interpretation

ISAT increases receipt of alcohol treatments without changes in drinking at week 24. Strategies to implement and enhance ISAT are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, alcohol use disorder (AUD) causes significant morbidity and mortality, especially among people living with HIV (PLWH).1,2 Evidence-based medication and counseling safely and effectively treat AUD among PLWH,3,4 yet treatments are rarely provided in HIV treatment settings.5 This occurs despite recommendations by national organizations for integrated care6 and reflects lack of provider experience, patient priorities, limited time and resources.5 Another concern is lack of uniform effectiveness of alcohol treatments that requires providers to adjust treatments based on patient response.

“Stepped care” treatment models may help address AUD among PLWH. Stepped care models increase or “step up” intervention components based on patient response and are effective for treating other chronic diseases (e.g., pain, hypertension) in primary care.7 Such models allow for different treatment components to be provided by multidisciplinary team members with expertise complementary to HIV providers’ skills. PLWH prefer integrated HIV and substance use treatment over referral8 and integration improves substance use outcomes.9 Few prior studies have evaluated the impact of integrated10,11 and stepped treatment models12 for AUD and none specifically in HIV treatment settings. The aims of this study were to examine the effectiveness of integrated stepped alcohol treatment (ISAT) versus treatment as usual (TAU) on alcohol use and HIV outcomes in PLWH and AUD. Our primary hypothesis was that ISAT would lead to fewer drinks per week compared to TAU.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

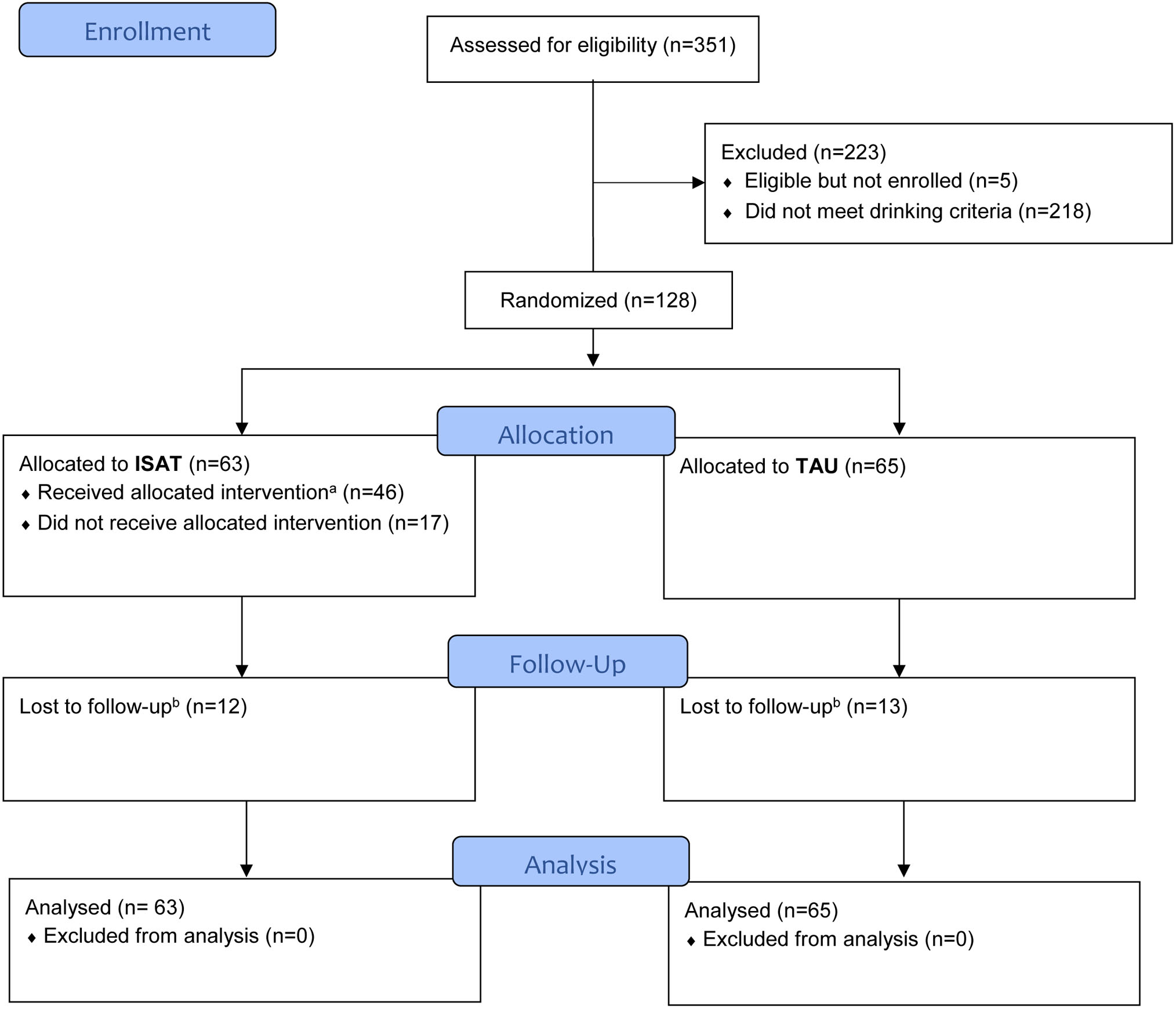

The Starting Treatment for Ethanol in Primary care (STEP) AUD Trial was conducted according to standards in the field,13 and the protocol and implementation experiences have been published.14,15 From January 28, 2013 through July 14, 2017, we recruited participants across five Veterans Health Administration (VA) Infectious Disease (HIV) Clinics, which cared for 400–1200 PLWH. Patients were invited to participate in the STEP AUD Trial if they met the following criteria: 1) were HIV positive; 2) a patient at one of the five participating Veterans Health Administration (VA) Infectious Disease (HIV) Clinics; 3) English speaking and able to provide written inform consent; and 4) met criteria for alcohol use disorder by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence and assessed using the Mini-Structured Clinician Interview for DSM (SCID) (Figure 1). Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1) were acutely suicidal or with a psychiatric condition that affected their ability to provide informed consent or participation in counseling interventions; 2) were currently enrolled in formal treatment for AUD, excluding self or mutual-help groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous); 3) had any medical condition(s) that would preclude completing the study or cause harm during the course of the study; and 4) were a pregnant or nursing woman, or woman who did not agree to use a reliable form of birth control. Since abstinence is recommended during pregnancy and specialty care might be required to achieve this goal this final criterion was put in place to avoid randomizing pregnant women to treatment as usual.

Figure 1. Participant Flow.

Notes:

a. Received allocated intervention: defined as attending at least one APM or MET visit.

b. Lost to follow-up: defined as not having any assessment at week 24 and afterwards through week 52.

Participants provided written and informed consent and were reimbursed $25 for baseline assessments and $50 for follow-up assessments. The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at Yale, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, and each participating site. The study was HIPAA compliant, and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01410123).

Randomisation and Masking

We used a web-based clinical trial management system17 to randomise patients in a 1:1 ratio to ISAT or TAU stratified by site. The randomisation sequence was concealed. Blinding of patients, providers or research assistants following randomisation was not possible.

Procedures

Eligible and consented patients were randomised to ISAT versus TAU. Regardless of treatment group, participants could receive any non-study services recommended by VA clinicians.

ISAT interventions were stepped up at predefined time points based on a priori criteria. Because this was an effectiveness trial, neither patients nor providers were specifically incentivized to attend or complete sessions as part of ISAT. ISAT was provided by VA clinicians and occurred in HIV clinics (i.e., co-located) whenever possible.

Step 1 consisted of Addiction Physician Management (APM), which focused on providing medication management along with alcohol treatment medications as an efficacious, but underutilized treatment option. APM was provided by Addiction Psychiatrists based on medication management used with buprenorphine in primary and HIV care. Following an initial assessment visit, subsequent 20-minute visits were scheduled weekly for two weeks, every other week for four weeks, and monthly up to a total of eight sessions over the 24-week treatment period. Alcohol treatment medications were prescribed at the discretion of the addiction psychiatrist, with instruction to prioritize Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved options (i.e., disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone) over non-FDA approved options when possible (i.e., topiramate, baclofen, gabapentin).

At the week 4 research assessment, those reporting heavy drinking (defined for men as ≥5 drinks per day and for women as ≥4 drinks per day) ≥1 in the prior 14 days by the Timeline Followback (TLFB) method, were stepped up to Step 2 which provided APM plus four sessions of psychologist-delivered Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET). MET sessions were scheduled every other week over the course of 6 weeks and were manual-guided with adaptations for PLWH. MET was chosen as the behavioral intervention given its appropriateness for addressing patients with low levels of motivation to change their drinking behavior. Skill building techniques, consistent with cognitive behavioral therapy, were used as indicated if patients exhibited motivation.

At week 12, those reporting heavy drinking at least once in the prior 14 days who had been advanced to Step 2 were advanced to Step 3. Step 3 included referral to a higher level of specialty services (e.g., intensive outpatient, residential treatment) at the Addiction Psychiatrists’ discretion and depending on local resources.

At the VA, every patient followed in a primary care clinic (such as HIV clinic) is screened annually with an AUDIT-C via a nurse-driven clinical reminder. This reminder includes prompts to conduct brief interventions or referral to addiction treatment as indicated.16 For patients enrolled in the study the HIV provider and/or clinic director were notified that their patient met criteria for AUD and should be considered for referral to VA alcohol treatment services at study entry.

We implemented procedures to monitor intervention fidelity and adherence. After initial training of psychiatrists and psychologists, the study team offered ongoing supervision and monitoring by teleconferences held every 1 to 2 months, provided structured encounter forms to guide intervention sessions, and conducted two site visits per site. MET sessions were digitally recorded, and a subset was reviewed with feedback provided by a study psychologist. We tracked the number of sessions attended. Pharmacy data were used to assess prescription of alcohol treatment medications in the 6 months prior to randomization through week 52. All reported adverse events were reviewed by the local site Principal Investigator and classified based on whether it was study related and by severity per standard Institutional Review Board guidance.

Outcomes

Consistent with prior literature, the primary outcome was drinks per week over the past 30 days at week 24 by TLFB.13 Additional drinking outcomes at week 24 and based on the past 30 days by TLFB included the percentage of participants with no heavy drinking days, drinks per drinking day, and percentage of days abstinent; phosphatidylethanol (PEth) level (an alcohol biomarker that reflects past 21 days of alcohol consumption with higher levels associated with greater quantities of alcohol use); VACS Index (validated measure of morbidity and mortality, with higher scores associated with increasing mortality risk);2 and undetectable HIV viral load (HIV RNA <50 copies per mL). We additionally assessed durability of the intervention by examining outcomes at week 52 (except for PEth, which was only collected at baseline and week 24). PEth was not used to determine study eligibility nor did clinicians or the coordinating center monitor PEth values during the study. Receipt of VA-based addiction treatment services, all-cause emergency department visits and hospitalizations were assessed by electronic medical record (EMR) data. Additional outcomes consistent with the overall study aims will be reported separately.

Statistical Analysis

To detect a mean difference of 15 drinks per week between the two treatment arms and given a conservative standard deviation of 30,18–20 a sample size of 64 participants in each group was needed to have 80% power at the two-sided 0·05 significance level. To account for a 20% dropout rate, our target enrollment number was 160 participants. Due to slower than expected accrual, we enrolled 128 participants providing 80% power to detect a difference of 16·8 drinks per week. We used descriptive statistics to describe baseline characteristics of the treatment groups, report attendance at scheduled intervention visits and proportion receiving alcohol treatment medications.

Our primary analysis was based on intention to treat (ITT), including all participants in the group to which they were randomised. We used linear mixed effects models to evaluate drinks per week, drinks per drinking day, percentage of days abstinent, and VACS Index with the assumption that missing data occurred at random. Analyses included fixed effects for intervention (ISAT vs. TAU), time (4, 12, 24, and 52 weeks), and the interaction of intervention with time. Additional fixed effects included baseline covariates: baseline outcome level, VACS Index and site. Random intercept and time effects were included for each participant with an unstructured covariance pattern for serial correlation. Linear contrasts were used to estimate intervention group differences and 95% confidence intervals at 24 weeks (primary) and week 52. Linear regression analyses were used to compare 24 week differences in PEth. For binary outcomes, we used generalized linear mixed effects models with the logit link function. In sensitivity analyses focused on the primary outcome, we excluded participants with a baseline PEth value <8ng/mL.

In post-hoc adherence adjusted analyses, we adjusted for intervention adherence to determine the effect of ISAT that would have been observed if all participants maintained an adequate level of intervention adherence. We used a marginal structural model (MSM) approach that employs inverse probability weights based on an individual’s propensity to adhere throughout the study.21 This creates a pseudo-population which removes the confounding effects of adherence. The adequate level of compliance of at least 30% of expected ISAT visits was chosen given this was the average level of adherence. Stabilized probability weights for less than 30% adherence to ISAT interventions were created from pooled logistic regression across each time period (i.e. weeks 4, 12, 24) with baseline (age, drinks per week, race, site, HIV viral load, any drug use, education and employment) and time varying (current and previous drinks per week) covariates. The MSM was then implemented by weighted generalized estimating equations (GEE). Odds ratios and 95% CIs are presented demonstrating the impact of ISAT if an adequate level of intervention adherence was maintained. All analyses involved 2-tailed tests of significance and were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Role of the funding source

STEP Trial researchers had primary responsibility for study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism staff (KJB) collaborated in the design of the study and provided comments for consideration in drafts of the manuscript. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Out of 351 patients who met the eligibility criteria, 128 were randomised (Figure 1). Despite a multi-pronged approach,14 we did not reach the target of 160 participants. Among the 128 randomised participants, 80% (103/128) completed the study (i.e., not lost to follow-up), with 113 (88%) providing data at week 4, 107 (84%) providing data at week 12, 98 (77%) providing data at week 24 and 74 (58%) providing data at week 52. Five participants withdrew and one died due to non-study related morbidity.

The mean age was 54 years (range, 23–70), 98% (125/128) were men, and 79% (101/128) were black. The mean AUDIT-C score was 8 (range, 4–12) and drinks per week was 32 (range, 1–129). Characteristics of participants randomised to ISAT and TAU did not differ, with the exception that participants randomised to ISAT were less likely to smoke tobacco than those randomised to TAU (60% [38/63] vs. 77% [49/65], p=0·049) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| No (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Integrated Stepped Alcohol Treatment (n=63) | Treatment as Usual (n=65) |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 62 (98·4%) | 63 (96·9%) |

| Women | 1 (1·6%) | 2 (3·1%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 12 (19·1%) | 12 (18·5%) |

| Black | 49 (77·8%) | 52 (80·0%) |

| Other | 2 (3·2%) | 1 (1·5%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (5·0%) | 7 (11·3%) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55·5 (9·0) | 52·0 (12·0) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 29 (46·0%) | 30 (46·1%) |

| >High school | 34 (54·0%) | 35 (53·9%) |

| Married or domestic partner | 10 (16·1%) | 15 (23·1%) |

| Employment statusa | ||

| Employed | 27 (42·9%) | 37 (56·9%) |

| Retired/disability | 24 (38·1%) | 18 (27·7%) |

| Student | 1 (1·6%) | 3 (4·6%) |

| Unemployed or unable to work | 11 (17·5%) | 7 (10·8%) |

| Alcohol·related measures | ||

| AUDIT-C score, mean (SD) | 7·4 (2·0) | 8·0 (2·1) |

| Alcohol abuse, current | 20 (31.7%) | 15 (23.1%) |

| Alcohol dependence, current | 43 (68.2%) | 50 (76.9%) |

| Other substance use, past 30 daysb,c | ||

| Smoke cigarettes | 38 (60·3%) | 49 (76·6%) |

| Cannabis | 20 (32·3%) | 21 (32·3%) |

| Cocaine | 12 (19·4%) | 14 (21·5%) |

| Heroin | 0 (0·0%) | 1 (1·5%) |

| Prescription opioids | 1 (1·6%) | 5 (7·7%) |

| Comorbid conditions and biomarkers | ||

| Hepatitis C co-infectiond | 18 (30·0%) | 15 (23·1%) |

| FIB-4score>1·45e,f | 36 (57·1%) | 34 (52·3%) |

| Depressive symptomsg | 22 (35·5%) | 16 (24·6%) |

| HIV related measures | ||

| VACS Index, median (range)f,h | 28 (0 – 77) | 24 (0 – 112) |

| Detectable HIV viral loadf,i | 21 (33·3%) | 24 (36·9%) |

| CD4 cell count, cells/uL, median (range)f | 590 (8 – 1450) | 496 (16 – 1364) |

Employment status, employment during past 3 years: assessed based on the Addiction Severity Index Lite-CF55

Smoke cigarettes: assessed based on the item: “Do you now smoke cigarettes (as of 1 month ago)?”

Other substance use, past 30 days: assessed based on the Addiction Severity Index Lite-CF55

Hepatitis C coinfection status – based on positive antibody and detectable HCV RNA viral load

FIB-4 score – a noninvasive measure of liver fibrosis calculated based on aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and platelets with scores greater than 1·45 concerning for liver fibrosis

Laboratory testing performed within 30 days prior to randomization date

Depressive symptoms determined using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 with score >9 defined as having depressive symptoms56

VACS index – validated measure of morbidity and mortality risk57

Detectable HIV viral load – defined as ≥50 copies per mL

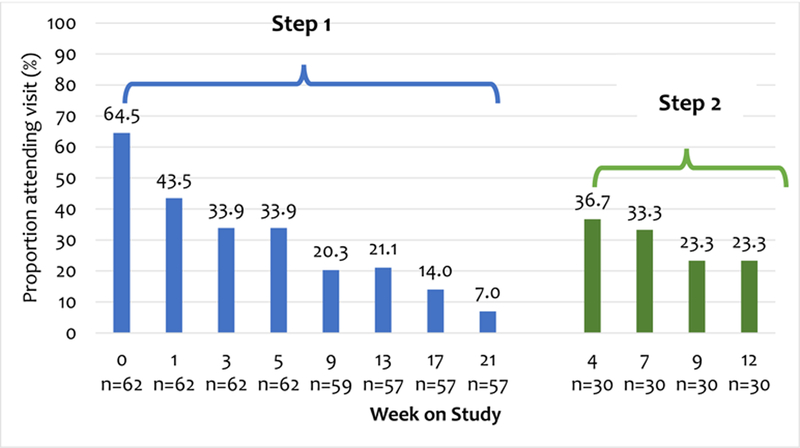

Regarding Step 1, the proportion of attended visits ranged from a maximum at the first visit to a minimum at the eighth visit.. Among those advanced to Step 2, over one third attended the first visit while less than one quarter attended the fourth visit (Figure 2). Fifty-two percent (30/57) met criteria for stepping up to Step 2 and 57% (17/30 met criteria for stepping up to Step 3. At week 24, participants randomised to ISAT were more likely to have received naltrexone, or acamprosate than those randomised to TAU (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the proportion of participants who received disulfiram, topiramate, baclofen, or gabapentin by treatment group at any time point. Adverse events were infrequent and none were considered likely to be study related (Supplementary Table 1 [Appendix, page 2])

Figure 2. Visit attendance among those randomised to integrated stepped alcohol treatment.

Notes: N reflects participants eligible for visit based on those active in the study and randomised to integrated stepped care and then stepped up to Step 2 (n=30). Step 1 = Addiction Physician Management (APM); Step 2 = Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET).

Table 2.

Past 6 month receipt of alcohol treatment medications at baseline and follow-up by treatment group

| Medication | Integrated Stepped Alcohol Treatment, N=63 No. (%) | Treatment as Usual, N=65 No. (%) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any alcohol treatment medicationa | |||

| Baseline | 11 (17.46%) | 10 (15.38%) | 0·75 |

| Week 4 | 20 (31.75% | 4 (6.15%) | 0.0002 |

| Week 24 | 32 (50.79%) | 17 (26.15%) | 0·004 |

| Week 52 | 16 (25.40%) | 13 (20.00%) | 0·47 |

| Disulfiram | |||

| Baseline | 0 (0·0%) | 0 (0·0%) | |

| Week 4 | 1 (1.59%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0·49 |

| Week 24 | 2 (3·17%) | 0 (0·0%) | 0·24 |

| Week 52 | 0 (0·0%) | 0 (0·0%) | n/a |

| Acamprosate | |||

| Baseline | 0 (0·0%) | 0 (0·0%) | |

| Week 4 | 1 (1.59%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0·49 |

| Week 24 | 6 (9·52%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0·01 |

| Week 52 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | n/a |

| Naltrexone | |||

| Baseline | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1·54%) | |

| Week 4 | 12 (19.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0002 |

| Week 24 | 20 (31·75%) | 5 (7·69%) | 0.0007 |

| Week 52 | 4 (6·35%) | 5 (7·69%) | 1·00 |

| Topiramate | |||

| Baseline | 0 (0·0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Week 4 | 1 (1.59%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0·49 |

| Week 24 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1·54%) | 1·00 |

| Week 52 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1·54%) | 1·00 |

| Baclofen | |||

| Baseline | 3 (4·8%) | 1 (1·54%) | |

| Week 4 | 1 (1·59%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0·49 |

| Week 24 | 1 (1·59%) | 1 (1·54%) | 1·00 |

| Week 52 | 1 (1·59%) | 1 (·54%) | 1·00 |

| Gabapentin | |||

| Baseline | 9 (14·3%) | 9 (13·9%) | |

| Week 4 | 6 (9.5%) | 4 (6.2%) | 0·53 |

| Week 24 | 12 (19·05%) | 14 (21·54%) | 0·73 |

| Week 52 | 11 (17·46%) | 12 (18·46%) | 0·88 |

Based on receipt of disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone, topiramate, baclofen, and/or gabapentin.

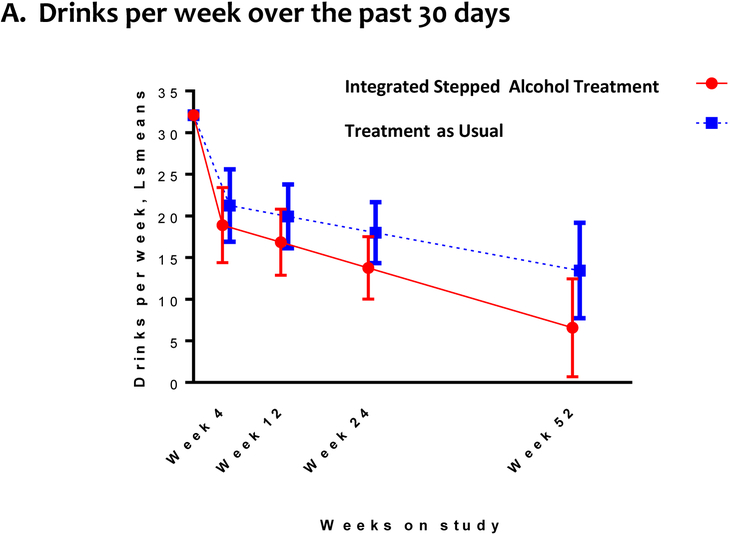

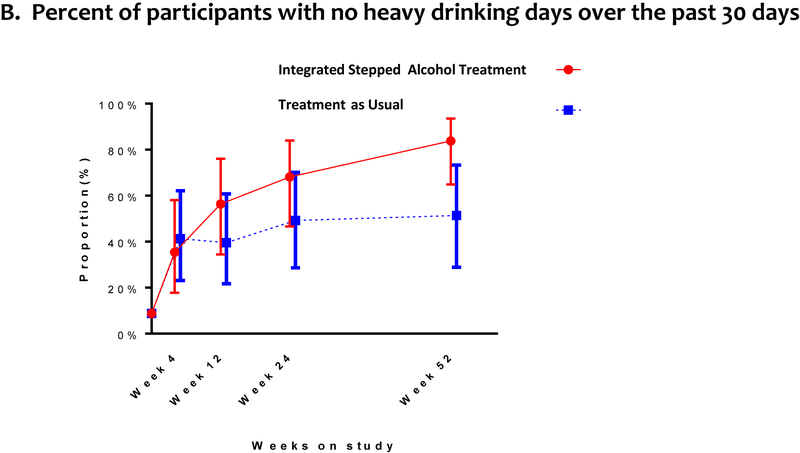

Alcohol consumption outcomes included: drinks per week, percent of participants with no heavy drinking days, drinks per drinking day, and percentage of days abstinent. Both groups reported decreased drinking over time. At week 24 (primary outcome), we did not detect a difference between the ISAT and TAU groups in drinks per week (Figure 3a, Supplementary Table 2 [Appendix, page 3]). Findings were consistent at week 52.

Figure 3. Drinking Outcomesa, b.

a. Random intercept and, for the continuous outcome, time effects were included for each participant with an unstructured covariance pattern for serial correlation. No heavy drinking defined as the absence of any heavy drinking days in the past 30 days, where a heavy drinking days is defined for men ≥5 drinks per day and for women as ≥4 drinks per day.

b. Bars reflect the associated 95% confidence intervals for the point estimates.

The percent of participants with no heavy drinking days was not higher among those randomised to ISAT compared to TAU at week 24, but was higher at week 52.

The drinks per drinking day was similar among those randomised to ISAT compared to TAU at week 24, but was lower at week 52.

The percentage of days abstinent was non-significantly higher among those randomised to ISAT compared to TAU at week 24; this difference was greater at week 52. At week 24, participants randomised to ISAT and TAU groups did not differ on PEth values, although the direction of the change was consistent with self-reported data.

HIV outcomes included VACS Index score and the proportion with an undetectable HIV viral load. At week 24, participants randomised to ISAT had similar VACS Index scores as those randomised to TAU. Findings were consistent at week 52. The proportion of participants with an undetectable HIV viral load did not differ among those randomised to ISAT and TAU at week 24; however, the proportion with an undetectable HIV viral load was higher at week 52.

With regards to healthcare use, at week 24, participants randomized to ISAT were more likely to have participated in formal outpatient alcohol treatment services than those randomized to TAU (Supplementary Table 3 [Appendix, page 4]). The ISAT and TAU groups did not differ on Emergency Department visit number, but the ISAT group had non-significantly fewer hospitalizations at week 24 compared to those randomised to TAU. Findings were consistent at week 52.

In the post-hoc inverse probability weighted MSM adherence analysis, adequate adherence with the ISAT intervention (i.e. at least 30% of intervention visits) resulted in fewer drinks per week at 24 weeks when compared to TAU (LSmean: 7·73 [2·30] vs. 15·56 [2·14]; AMD [95% CI]= −7·83 [−14·29, −1·39], p=0·017). In the sensitivity analyses excluding patients with a baseline PEth value <8ng/mL, results from analyses examining differences by treatment group on drinking outcomes were similar to the main analyses.

DISCUSSION

In this sample of PLWH and AUD receiving alcohol treatment in HIV clinics, ISAT resulted in a greater provision of alcohol treatment medication, counseling, and formal outpatient alcohol treatment services with delayed improvements in drinking and HIV-related outcomes as compared to TAU. Although we did not detect differences in drinks per week at week 24 or 52, there were observed improvements by week 52 in the percentage of patients with no heavy drinking days, number of drinks per drinking day, and percentage of days abstinent. Importantly, we also observed that participants randomised to ISAT were more likely to achieve an undetectable HIV viral load by week 52. Moreover, the value of a stepped care strategy was demonstrated, as nearly half of ISAT patients met criteria for Step 2 and one quarter advanced to Step 3. Given lack of provision of alcohol treatments in HIV treatment settings,5,22 our adherence adjusted analyses and week 52 results, our findings on alcohol consumption and HIV outcomes indicate that ISAT holds promise, especially when patients receive treatment services.

The adverse impact of alcohol on the HIV care continuum and other health outcomes among PLWH is well documented. Yet, few studies have sought to integrate alcohol treatment into HIV settings, and studies have generally focused on promoting either counseling or medication-based interventions.4,23,24 We note, however, that medication combined with counseling for the treatment of AUD is standard of care.25 The STEP AUD Trial extends these results by providing evidence for a new approach to coupling alcohol treatment in a manner that is responsive to patient needs. Further, ISAT can be adapted to site-specific resources. For example, APM is designed to be provided by a trained HIV provider or an addiction medicine/psychiatrist specialist depending on resources. In addition, APM allows for flexibility regarding which medication is prescribed and is adaptable as new medications become available. Similarly, the MET sessions could be provided by anyone trained in motivational interviewing (e.g. social worker, psychologist).

Our findings also provide insight into treatment of AUD among patients primarily identified via screening rather than seeking alcohol treatment. Despite the integrated nature of the intervention, recruitment and visit adherence did not meet expectations. We note that our study was focused on PLWH attending routine visits, where many patients may have low motivation to address alcohol use given their underappreciation of its potential harms.26–28 In addition, although nearly 45% of ISAT patients accepted an FDA-approved medication for AUD and 51% received any medication for alcohol, many did not. Further, just one third of the patients attended at least two MET sessions. Although this represents important improvements in the provision of interventions to address alcohol use, barriers to providing treatment exist. These likely reflect patient, provider, and logistical factors.15,27 Notably, when ISAT participants attended at least 30% of scheduled visits, significant decreases in drinks per week were achieved with overall findings favoring ISAT across outcomes Also, delayed effects of ISAT were observed on important drinking and HIV outcomes regardless of treatment adherence. Together, the data support the need for integrating alcohol treatments with a stepped care approach into HIV treatment settings as an important strategy for improving both drinking and HIV outcomes in this population.

Our study has important strengths. First, it was conducted in five sites, and we found no effect of site on our outcomes. Second, we recruited patients who were not seeking alcohol treatment, which reflects a common phenomenon in HIV clinics. Third, ISAT is a novel and flexible approach to addressing alcohol use that may have implications for primary care and elsewhere (e.g., HCV treatment settings). Fourth, we augmented patient assessments with EMR data to capture process measures (i.e., medication receipt) and laboratory data.

Our study, however, should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, those enrolled were predominantly men. Second, it was conducted in VA-based HIV clinics, and the findings may not generalize to non-VA based settings. However, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program funding promotes an infrastructure for supporting mental health and substance use treatment services for patients with the greatest needs through diverse settings. Third, PEth was not used to determine study eligibility, verify self-report or as part of clinical care. Not all patients had an elevated PEth at study entry, indicating self-report may be misleading. Since PEth is relatively new and not routinely used in clinical trials or clinical care, its use here supplemented self-report. Recent work demonstrates that PEth along with self-report can identify patients with increased mortality risk.29 Notably, our findings did not vary when patients with PEth values <8ng/ml were excluded. Fourth, nearly 20% of participants were lost to follow-up. Missing data is common in alcohol treatment studies, and we applied robust methods that are standard in the field and achieved an 80% completion rate.13,30 Finally, we did not achieve our enrollment target and therefore Type II error is possible.

In conclusion, ISAT increases alcohol treatment receipt among PLWH with AUD with evidence of delayed effects on drinking and HIV outcomes. Efforts to promote implementation of and adherence to ISAT in HIV treatment settings are warranted.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

Untreated alcohol use disorder is associated with poor HIV outcomes in people who live with HIV (PLWH) and ongoing HIV transmission. Counseling and medication treatments are rarely delivered in HIV treatment settings. In addition, efficacy is not uniform across patients indicating that stepped treatment approaches which are responsive to individual patient needs may be required. We searched PubMed for studies focused on addressing alcohol use in HIV using the search terms “HIV” and “alcohol” and “randomized” in the title as of February 18, 2019. Our search yield eighteen articles, none of which incorporated a stepped care approach to address alcohol in HIV treatment settings.

Added value of this study

Stepped care models allow for treatments to be tailored to patient responses and serve to maximize resources. We found that integrated stepped alcohol treatment (ISAT) was associated with a greater delivery of alcohol treatment medications and counseling compared to treatment as usual (TAU) for 128 PLWH who also have alcohol use disorder. No differences between groups were observed in drinks per week at 24 weeks (primary outcome) or 52 weeks. Compared to TAU, the PLWH in the ISAT group had improvements in drinking (no heavy drinking days, drinks per drinking day, and percentage of days abstinent) and HIV related (proportion with an undetectable HIV viral load) outcomes at week 52. This is the first study evaluating the effectiveness of ISAT to address alcohol use among PLWH and alcohol use disorder.

Implications of all the available evidence

Based on the literature to date, alcohol treatments can be feasibly delivered in HIV treatment settings and produce modest benefits on alcohol and HIV outcomes. Stepped care strategies warrant enhancement and future implementation to optimize outcomes among PLWH with alcohol use disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the patients and providers who participated in this research.

This work was generously support by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant #U01AA020795, U01AA020790, U24AA020794). EJ Edelman was supported as a Yale-Drug Abuse, HIV and Addiction Research Scholar (NIDA grant #K12DA033312) during the conduct of this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

DATA SHARING

With written request (https://medicine.yale.edu/intmed/vacs/groups/RequestingData.asp_) and after review and approval by the Principal Investigator and VACS team, a data dictionary defining each field in the analytic data set and de-identified individual participant data may be made available after findings of the main analyses have been published. Details of the study protocol have been previously published;29 and our template for obtaining written informed consent will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, Bryant K, Lira MC, Samet JH. Alcohol Use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection: Current Knowledge, Implications, and Future Directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2016; 40(10): 2056–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, et al. Risk of mortality and physiologic injury evident with lower alcohol exposure among HIV infected compared with uninfected men. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016; 161: 95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey KB, Johnson BT, Carey MP, Team MR. Behavioral Interventions Targeting Alcohol Use Among People Living with HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Behav 2017; 21(Suppl 2): 126–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edelman EJ, Moore BA, Holt SR, et al. Efficacy of Extended-Release Naltrexone on HIV-Related and Drinking Outcomes Among HIV-Positive Patients: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. AIDS Behav 2019. January 23(1): 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chander G, Monroe AK, Crane HM, et al. HIV primary care providers--Screening, knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to alcohol interventions. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016; 161: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. Washington, D.C, 2006, Washington, D.C., National Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bair MJ, Ang D, Wu J, et al. Evaluation of Stepped Care for Chronic Pain (ESCAPE) in Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Conflicts: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(5): 682–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drainoni ML, Farrell C, Sorensen-Alawad A, Palmisano JN, Chaisson C, Walley AY. Patient perspectives of an integrated program of medical care and substance use treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014; 28(2): 71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldfield BJ, Munoz N, McGovern MP, et al. Integration of care for HIV and opioid use disorder: a systematic review of interventions in clinical and community-based settings. AIDS 2018. December 21 [epub ahead of print]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley KA, Ludman EJ, Chavez LJ, et al. Patient-centered primary care for adults at high risk for AUDs: the Choosing Healthier Drinking Options In primary CarE (CHOICE) trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017; 12(1): 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter M, et al. Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 310(11): 1156–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coulton S, Bland M, Crosby H, et al. Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of Opportunistic Screening and Stepped-care Interventions for Older Alcohol Users in Primary Care. Alcohol Alcohol 2017; 52(6): 655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witkiewitz K, Finney JW, Harris AH, Kivlahan DR, Kranzler HR. Recommendations for the Design and Analysis of Treatment Trials for Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015; 39(9): 1557–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelman EJ, Maisto SA, Hansen NB, et al. The Starting Treatment for Ethanol in Primary care Trials (STEP Trials): Protocol for Three Parallel Multi-Site Stepped Care Effectiveness Studies for Unhealthy Alcohol Use in HIV-Positive Patients. Contemp Clin Trials 2017; 52: 80–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelman EJ, Hansen NB, Cutter CJ, et al. Implementation of integrated stepped care for unhealthy alcohol use in HIV clinics. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2016; 11(1): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Alcohol Misuse: Primary Care of Veterans with HIV. 2011.

- 17.Nadkarni PM, Brandt C, Frawley S, et al. Managing attribute--value clinical trials data using the ACT/DB client-server database system. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1998; 5(2): 139–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol 1997; 58(1): 7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006; 295(17): 2003–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JD, Grossman E, DiRocco D, et al. Extended-release naltrexone for treatment of alcohol dependence in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat 2010; 39(1): 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rochon J, Bhapkar M, Pieper CF, Kraus WE. Application of the Marginal Structural Model to Account for Suboptimal Adherence in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2016; 4: 222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams EC, Lapham GT, Shortreed SM, et al. Among patients with unhealthy alcohol use, those with HIV are less likely than those without to receive evidence-based alcohol-related care: A national VA study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017; 174: 113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chander G, Hutton HE, Lau B, Xu X, McCaul ME. Brief Intervention Decreases Drinking Frequency in HIV-Infected, Heavy Drinking Women: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 70(2): 137–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korthuis PT, Lum PJ, Vergara-Rodriguez P, et al. Feasibility and safety of extended-release naltrexone treatment of opioid and alcohol use disorder in HIV clinics: a pilot/feasibility randomized trial. Addiction 2017. June; 112(6): 1036–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: A brief guide In: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, editor. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15–4907 ed; Rockville MD; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fredericksen RJ, Edwards TC, Merlin JS, et al. Patient and provider priorities for self-reported domains of HIV clinical care. AIDS Care 2015; 27(10): 1255–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliott JC, Aharonovich E, O’Leary A, Johnston B, Hasin DS. Perceived medical risks of drinking, alcohol consumption, and hepatitis C status among heavily drinking HIV primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014; 38(12): 3052–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chokron Garneau H, Venegas A, Rawson R, Ray LA, Glasner S. Barriers to initiation of extended release naltrexone among HIV-infected adults with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018; 85: 34–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eyawo O, McGinnis KA, Justice AC, et al. Alcohol and Mortality: Combining Self-Reported (AUDIT-C) and Biomarker Detected (PEth) Alcohol Measures Among HIV Infected and Uninfected. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 77(2): 135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallgren KA, Witkiewitz K. Missing data in alcohol clinical trials: a comparison of methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2013; 37(12): 2152–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.